Labour Demand & Supply Lecture

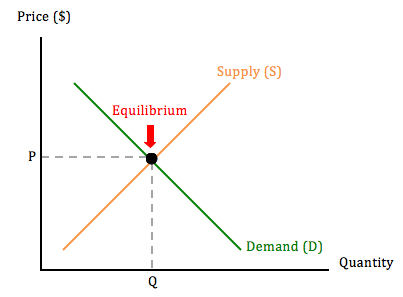

Labour economics seeks to understand the functioning of labour markets, and how such impacts on supply/ demand and wages. As with other goods in the economy, labour demand and supply can be graphically represented as shown below:

Figure 1 - Visualisation of supply/ demand.

In this case, the price (i.e. wage rate) offered to the employee will be dependent on the supply of labour in that sector compared with the demand for that labour. Essentially, if demand for a specific labour is high and supply is low, then the expectation would be that the wage rate would increase to attract more supply into the sector - read Sloman et al (2013). Specifically, when talking of labour, skills could be considered as the commodity which is being traded. Essentially, to encourage more workers to acquire a specific skill, the employer will offer a higher wage rate. An example of this may be a manufacturer offering a high salary level to attract more workers to acquire the needed skills, meeting demand. Labour economics is important given the result it has on wages, income and unemployment, with many governments around the world seeking full employment. As suggested by economic models such as Solow Growth, full employment would result in greater employment in the economy, in turn rising income, and reducing welfare that may be associated with unemployment benefits.

The above description would suggest that the labour market is operating perfectly. However, there can be inefficiencies in the system that leads to an imperfect market; consider reading Sloane et al (2013). For instance:

(1) Compensating differentials: a worker may be given lower wages because he is receiving part of his/ her compensation in the form of other (hard-to-observe) characteristics of the job, which may include lower effort requirements, more pleasant working conditions, better amenities etc.

(2) Labour market imperfections: two workers with the same human capital may be paid different wages because jobs differ in terms of the role, and from this their productivity and pay. For instance, a leading accountancy business may pay their worker more than that at a smaller firm, even though the specification is the same.

(3) Direct discrimination: employers may pay a lower wage to a worker because of the worker’s gender or race due to their prejudices.

However, with this, the elasticity of demand must also be considered. This elasticity will be dependent on the business in question. For instance, a business will consider labour costs as a % of total costs. If the business is in a highly competitive industry whereby the prices of their products are elastic, then they may have little power to push through higher prices if needed to offset higher wages. What could also be mentioned here is that with globalisation there are now a number of choices available to businesses. For example, if workers in the UK demand higher wages, then the business may consider relocating their operations internationally, to a country such as China/ Indonesia where the wage rate may be lower. These finished products can then be imported back into the UK and sold at the current price, essentially reducing the costs for the business.

Finally, there is also a level of substitution which must be considered between the cost of labour and capital substitution. For example, labour demand will be more elastic when the business can quickly substitute the labour for capital inputs; i.e. replacing workers with machinery. If wages rise too high, then businesses may look to invest into machinery or automate some processes to reduce the costs of labour. To visualise this, consider the UK retail sector, a sector which is coming under recent pressure from increase competition, rising inflation and slowing economic growth. At the same time, the UK government is seeking to rise the National Living Wage at a time when further growth in UK worker productivity is providing elusive.

With this in mind, consider a retailer who facing increasing wage costs while the productivity of that worker is not necessarily increasing, or bringing in extra revenue to compensate for the higher costs. Ultimately, the profitability of the business will decrease, prompting management to consider cost cutting measures. This could impact on labour, especially as mentioned above if there are chances to substitute labour for capital, or to move the labour to a cheaper location.

Taking the examples above, the labour market can be considered in the microeconomics or macroeconomics sense. Macroeconomics refers to the overall economy and so consider interrelations between the labour market, trade and money markets. For instance, the government can intervene in the economy to change the macroeconomic situation, be it introducing a set minimum wage to incentive more engagement within the labour force; make changes to the education sector to increase the skill-set within the economy, or change policies in business/ taxes etc., i.e. free-trade agreements to make the economy more competitive and increase aggregate demand. Microeconomics focuses on the individual businesses/ workers, considering their role in the labour force.

Need Help With Your Economics Essay?

If you need assistance with writing a economics essay, our professional essay writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Essay Writing Service can help today!

1.1 Human Capital

The basic approach to labour economics would consider human capital as a set of skills/ knowledge that could be used to increase productivity from a worker. This is a useful starting point, however there are some researchers who consider an alternative view:

- The Becker View – The idea here is that human capital is directly related to the production process, and should be viewed as a stock of knowledge in the worker. An un-dimensional object represents this, be it knowledge, or know-how etc.

- The Gardener View – this view is similar to that above, however there is this idea that capital can be split into mental vs. physical abilities, meaning that some may be dimensional. The idea here could be that some workers may be better suited at a task given their abilities; be it their strength etc.

- The Schultz/ Nelson-Phelps View – human capacity is viewed as the capacity to adapt; suggesting that a business is able to adapt its workforce to a changing environment, be it through training/ education.

The main difference between these theories is how their distinguish the source of human capital, be it something which is instilled within a worker from birth, or be it something which can be developed with education, training. This is an interesting concept in many advanced nations as the economy transitions. For instance, consider the former mining towns in the UK. Some of these areas continue to suffer with persistently high unemployment even now given failures in retraining former miners to appeal to new industries, i.e. IT. This shows that it is not always so easy to acquire the new skills in the workforce; there are barriers to overcome.

For instance, one may be a barrier into education. A former miner may seek to retrain for employment in the financial industry, however they may be stopped by the cost of the training needed, be it professional courses, or further education such as a University degree. In this case, the worker needs to consider the options available to them and the differential of education; be it the extra income earned which can then be traded off with the costs of education. However, by doing this, it could be noted that education/ training prefers the young. For instance, consider two workers, one who is 22 and one who is 40; also assume that the retirement age is 66. Each considers further education at a cost of £50,000 that they hope will increase their employability, getting them on average £2,000 per year. For the 40 year old who has 26 years of work left, an extra £2,000 per annum would represent an extra £52,000 over their working life, one marginally more than the cost of the education, while for the 22 year-old it is £88,000; providing a greater financial benefit.

1.2 Wage structure

When it comes to determining the wage structure, the wage rate offered by the business will be dependent on the supply/ demand fundamentals of the market. So, as mentioned if there is a shortage of labour in a specific industry, the business will try and attract more labour through increasing the wage rate. However, there are now other factors to consider. For instance, with globalisation and automation, there are now substitutes/ choices available to businesses which may provide a ceiling to wage rates.

In some industries, wages may be kept lower given the productivity, and so the payback of the worker to the business. For instance, workers in hospitability/ service sectors are generally paid less than counterparts in finance given that they return less financially to the business. According to the neo-classical view on labour markets, a worker will earn a wage which is equal to their marginal product of labour, however this is assuming that the labour market operates in a perfect market. In reality, this may not hold, with businesses seeking to make abnormal profits from workers, which in turn will see them pay a wage rate below the marginal product of labour.

Furthermore, there is the argument that some manufacturing roles may command a lower wage rate given that the process being undertaken could be replaced by machinery. As noted, if the wage rate does move too high, then it may be financially viable for the business to substitute labour for capital.

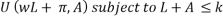

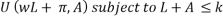

A neoclassical model can be considered here:

‘U’ refers to total utility, suggesting that the worker will look to maximise their total utility. This will be done given the parameter of total time available (denoted by k), with the worker choosing between working (L), and leisure time (A). Essentially, the choice will be dependent on the wage rate offered for working (denoted as w), compared with the income that could be earnt from non-labour sources, also seen as the utility which could be derived through leisure (π). What this equation suggests is that the choice for the worker is a trade-off; if wages do increase higher then there is a higher incentive to work more. It could be considered here that a driver behind the introduction of the National Living Wage in the UK has been to increase participation in the workforce, making it financially beneficial for those on benefits to seek work.

Figure 2 below shows an example of the backward bending labour supply curve. So, say that a worker begins at point S, whereby their wage equals W0 and so they work L0. However, as their wage rate is increased they are incentivised to work more, seen as the substitution effect given that the worker will substitute leisure time for labour. This will continue until they reach point T., when the substitution effect may be displaced by the income effect. After this point, a higher wage will push the worker to cut back on their hours worked given that they are happy with their current income level. It could be said that the marginal utility of an extra leisure hour here is greater than the utility from dedicating more hours to labour.

Figure 2 - Backward bending labour supply curve.

1.3 Unemployment types

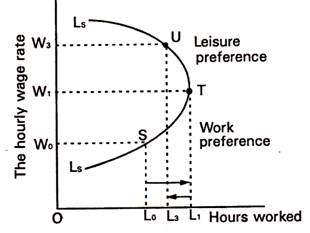

A number of types of unemployment can be discussed, influenced by either macro, or micro events. For instance, cyclical unemployment can be mentioned. This type of unemployment is created by a general downturn in the economy, causing aggregate demand to fall. With this, there is less need for labour in the economy, and so unemployment will rise. Taking UK unemployment data (see below), the unemployment rate peaked at 8.5% during the financial crisis, before falling back in the following years, however this was lower than the 11.9% recorded in 1984. Some others may also refer to this situation as ‘Demand Deficient Unemployment’, essentially suggesting that there is insufficient aggregate demand for full employment to be achieved in the economy. However, this may be dependent on the economy in question, and the components which are driving aggregate demand.

Figure 3 - Data table acquired from the ONS (2017)

Aggregate demand can be seen in the following equation:

Aggregate Demand = Consumer Spending + Investment + Government Spending + (Exports - Imports)

When it comes to the UK, the main driver of aggregate demand has been consumer spending, with recent commentary from the Bank of England suggesting that the UK needs to drive future growth from investment and trade, with exports being increased. This is important to consider given that continued globalisation has allowed some countries to increase their employment through international demand as opposed to just domestic aggregate demand; for instance, China. However, globalisation has come with negatives to the labour market, negatives which can be seen when structural unemployment is considered.

Structural employment is caused when certain industries decline, potentially by long-term changes in the market. Following on from the example of China above, it can be noted that the UK has lost a number of manufacturing roles over the years as businesses relocate to China where wages are lower. With this, jobs are transferred abroad, leaving structurally employed workers. The long-term impact of this will be dependent on a number of factors, including the ability for such workers to be re-trained, or the other opportunities which may be available to them in the local economy. However, in some cases this structural unemployment could become long-term, even if the economy is performing well. There are a number of reasons to mention here, including (1) that it may be difficult to retrain workers into sectors which may offer them comparable benefits (i.e. pay) to their previous roles, or (2) the local economy may have few other opportunities available, with the loss of the manufacturing plant hitting other areas of the local economy such as services.

This can also be seen as regional unemployment. For instance, if the UK is considered, coalminers from South Wales or ship workers from the North East are cases of regional unemployment, with the region unable to ‘regenerate’ given a lack of opportunities available to displaced workers. Similar to this could be seasonal unemployment which may also be seen as regional. For instance, in the UK, seaside resorts such as Blackpool/ Cleethorpes suffer from seasonal unemployment given the need for more workers during the summer months. Seasonal employment could be seen in industries ranging from tourism, to farming and construction.

Three other types could be seen as classical, frictional and voluntary. Classical unemployment is built with the traditional supply/ demand model in mind. The main idea here is that unemployment will occur when the wage rate being demanded by workers is too high. Some theories argue that this type of unemployment is the blame of the employee’s for demanding too high of wages; which in turn restricts from the economic reacting full production. This could also be considered when the introduction of a minimum wage is considered. For instance, in the UK the trajectory of the UK National Living Wage has prompted some worries that it will lead to higher unemployment as some businesses, particularly those in the service/ hospitality sectors looks to cut jobs and seek to increase productivity from remaining staff to remain profitable.

Frictional unemployment is seen when a worker has lost their job and in the process of searching, and applying for a new role. Given the process, this is not instant, instead the worker may be classed as unemployed for a number of months while this move from one job to another. Given this, many economies consider full employment to be between 3-4%, with commentary recently from the U.S. considering that the economy may be moving close to full employment as unemployment falls to 4.4%. Commentators consider full employment to be closing in when wage growth increases in the economy, pointing to a shortage of workers.

Finally, voluntary unemployment must also be considered, which may be seen when some people choose to remain out of the labour force. For instance, in the UK the labour participation rate is --, while that of the U.S. is 62.8%. In some communities there may be customs/ social reasons which deter some from entering the workforce, i.e. women. On the other hand, there may be discrimination which could deter others from participating including older workers, all which will decrease the participation rate in the economy.

1.3.1 Example - U.S. Economy

As mentioned, the U.S. unemployment rate is currently at 4.4%, with some commentators mentioning that this could be a sign of full employment within the economy. However, as shown in the chart below, while the participation rate is increasing, it remains lower than the % seen pre-crisis. Taking this into account, it could be considered that the current 4.4% unemployment rate is under reporting the actual rate. For instance, if the wage rate was to increase in future, then more workers may seek to re-enter the workforce, pushing up the supply of workers and potentially increasing the unemployment rate if there isn’t sufficient demand.

Need Help With Your Economics Essay?

If you need assistance with writing a economics essay, our professional essay writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Essay Writing Service can help today!

1.4 Labour Productivity and Production Frontiers

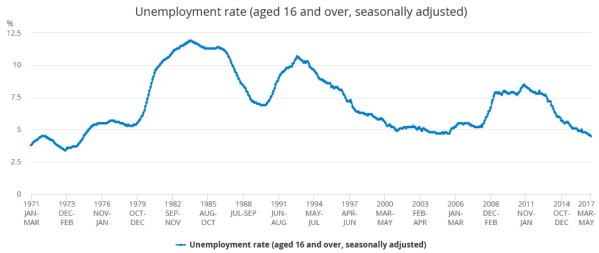

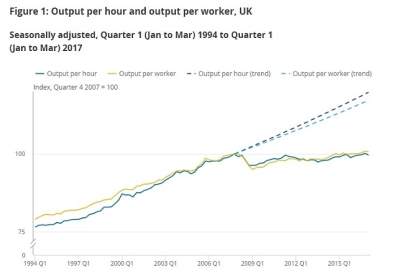

The production frontier provides a visualisation of the possible production of goods in an economy. Essentially, given the current inputs, the economy can produce up to any combination on the frontier curve. However, it could be mentioned that for workers to achieve above inflation pay increases, raising living standards, productivity needs to be increased. By increasing productivity, the worker is producing more goods for the business, in turn bringing in more revenue. The table below has been taken from the Office of National Statistics (UK), showcasing the recent slowdown in UK productivity growth from the 2009 recession. Taking the data, productivity in 2007 has only just surpassed the level seen in Q4-2007 when the index was set at 100.

Figure 4 - Source ONS (2017). UK Labour Productivity

The main issue with this slowdown in productivity is that it hinders further expansion in the economy, with the dotted line above showcasing how productivity may have been if it continued on its pre-crisis trajectory. Furthermore, there is also a linkage with wages; if the worker is more productivity they earn more for the business, allowing the business to pay them more. With this, the consumer may spend more as their income increases, driving aggregate demand in the economy and further increases the size of the economy. So, thinking this way it can be concluded that productivity growth is vital for long-term sustainable growth. This can be seen in the Solow Growth Model, who considers that long-term sustainable growth can only be achieved through two inputs, namely labour and capital. For a country to continually increase the size of their economy, they need to either (1) increase the size of the labour force, or (2) invest into the current labour market to expand productivity through capital expenditure (hereafter CAPEX).

When productivity is considered there are a number of ways in which a business can seek to raise their levels. For instance, the general assumption is that productivity fell during the 2008 financial crisis given that businesses reduced investment given weaker economic fundamentals, restricting the deployment of new technology. It could be noted that prior to the crisis, a continued rise in productivity had been supported by greater implementation of new technology, in many cases allowing for tasks to be automated. Other factors which could be considered are greater education/ or training to the workforce. However, there is a downside, with recent reports noting how greater automation could lead to greater job losses in the future, in turn increasing unemployment. Specifically, some economists now worry over how advancements in robotics may impact on employment within specific industries, be it manufacturing or on the service sector, i.e. hospitality.

1.5 Labour Mobility

Labour mobility refers to the ease with which workers are able to move around an economy, or internationally, a theory which will link directly with the economics of unemployment and labour supply/ demand. It is important to study labour mobility as it can be a major influencer on production, productivity and so economic growth. When it comes to mobility, there are two main types to focus on, namely geographical and occupational. Geographical mobility refers to the worker’s ability to work in a particular location, be it domestic or international etc. Occupational mobility refers to the worker’s ability to change job types, i.e. from manufacturing to retail etc.

1.5.1 Example in the UK

For example, consider a worker in the UK who currently lives in Manchester, but has now been offered a job in London. There are a number of barriers which could stand in the way of the worker moving, be it finding an affordable house in London, family ties in Manchester, social reasons, money etc. In a perfect economy, there would be no barriers allowing the worker to move into this job, although this is not the case. When international moves are considered, then there are other complexities to consider, i.e. visas, local cultures etc.

Occupational mobility could also be considered here. Assume that the worker had previously worked in a manufacturing plant, however after the plant closed and moved production to China the worker was left unemployed. To regenerate the local economy, IT/ financial businesses are now being attracted to set up offices in the local area. However, there are still barriers here, mainly when it comes to the worker transferring their skills, or developing new skills which would be required by these occupations.

Taking this into account, there are a number of reasons why geographical mobility does matter to labour market:

- Increase the labour supply: The mobility of labour could be important for economic development when it comes to expanding the supply of labour in an economy. For instance, the Chinese economic growth story was supported by urbanisation, and by the movement of people from rural villages into the burgeoning cities. This mobility of labour increased the available workforce to manufacturers in China, providing the country will a large pool of cheap labour.

Added to point (1) above comes the concepts of specialisation and comparative advantage. In the case of China, the supply of cheap labour into its burgeoning cities allowed it to develop a comparative advantage globally in the manufacture of a number of consumer goods, leading to specialisation which supported its export-growth model. Specialisation can also be noted in a number of other countries, especially when it comes to the development of a ‘cluster’ of business. For instance, London in the UK holds a ‘cluster’ of financial businesses, a cluster which in turn has been supported by the supply of skilled labour, supported through mobility, both domestically in the UK and internationally, particularly given the EU, and the free movement of people.

- Unemployment: Secondly, mobility matters given the impact that it could have on unemployment. As mentioned above, there could be cases where the supply of labour exceeds demand, requiring the mobility of labour. Furthermore, while there may be the labour supply in the local economy, the current supply may not necessarily be trained up to meet demand, which in turn may require mobility of labour.

- The mobility of labour also becomes interesting when discussing productivity of labour. For instance, the examples above with China have mentioned how the country was able to build a comparative advantage in the production of manufactured goods given the large pool of cheap labour. At the same time, productivity also comes into question, especially when the development of a business ‘cluster’ occurs. The mobility of labour into a specific geographical area could create an advantage for businesses seeking to locate. For instance, Silicon Valley in San Francisco has continued to expand as new businesses are attracted to the area given the local pool of skilled labour, created through the mobility of labour.

A reduction in geographic restrictions can be reached in several different ways. Between countries, it is accomplished through treaties or economic agreements. Countries can also increase the number of worker visas available, or reduce the requirements of receiving one. For example, countries that are part of the European Union have fewer restrictions on the movement of labour between members, but can still place tight restrictions on labour movement from non-member countries.

The effectiveness of improved geographic mobility will ultimately depend on individual workers. If economic opportunities are not available in a different country or in a different part of one's current country, the likelihood of an employee wanting to make a change will be diminished.

There are also a number of factors which are impacted by occupational mobility. For instance, occupational mobility will be key to transform an economy, providing workers with new skills and new opportunities which could avert unemployment. Occupational mobility could provide support to nascent industries wanting to grow; for example, the movement away from labour intensive manufacturing to more high-end technical manufacturing and engineering. Mobility could provide SME’s[1] with the workers they need to expand their operations. If not, a shortage of workers could impact on the production possibility, and productivity of the business, which in turn may impact on the competitiveness of the business.

Occupational mobility could also aide businesses in keeping costs lower, especially through lower wages. As mentioned with supply/ demand, if there is a supply shortage of workers, then the expectation would be that the wage rate would need to increase to attract more workers. However, if the wage rate does increase too high, then producing the items may become unprofitable, and so business may fail to reach full production. However, by increasing the supply of labour then the wage rate can decrease, reaching an equilibrium which is beneficial for both the business and the worker.

Occupational mobility can be restricted through regulations. Licensing, training or education requirements prevent the free flow of labour from one industry to another. For example, restrictions limit the supply of physicians, since specialized training and licensing is required to work in that particular profession. This is why physicians can command higher wages, because the demand for physicians coupled with a restricted supply increases the equilibrium wage. This funnels unqualified members of the labour force into industries with fewer restrictions, keeping the wage rate lower through a higher labour supply compared to the amount of labour demanded.

1.6 Labour Unions and Collective Bargaining

When it comes to labour markets, labour unions who are also known as ‘Trade Unions’ are an important factor. Some industries use trade unions as a means of collective bargaining when it comes to pay and other issues in the workplace. Trade unions are organisations which seek to improve the real incomes of workers, provide job security etc. In the UK, some of the biggest unions include ‘Unite’ and UNISON, the public sector trade union, however there are also specific unions for specific roles, including the NUT, who represent teachers.

However, there has been a large decline in union membership over the last few decades which in turn has eroded some of the bargaining power which these unions would hold on employers. Unions might seek to exercise their collective bargaining power with employers to achieve a mark-up on wages compared to those on offer to non-union members. For this to happen, a union must have some control over the total labour supply. In the past this was possible if a union operated a closed shop agreement with an employer – i.e. where the employer and union agreed that all workers would be a member of a particular union. However, in most sectors, the closed shop is now history. With this, the choices available to trade unions has diminished when it comes to action.

Focusing on 2017, the UK has already seen a number of actions involving trade unions, with the most popular being strike action which as touched upon above would be seen as restricting the supply of labour. Walkouts have already been seen on the railway in Northern/ Southern Rail strikes, with British Airways, and within the public sector; be it the NHS or Education.

1.7 Chapter Summary

This section will now provide a summary on the economics behind labour markets.

To start, the first section mentioned that labour markets are determined like goods, with supply/ demand. Ultimately, this relationship will help determine the wage rate offered to the worker for the role. However, as touched upon, this has become an issue in many advanced economies as productivity growth has slowed. Taking the latest figures from the UK, productivity slid by 0.5% in Q1-2017, with some commentators suggesting that it takes a British worker 5 days to produce what a worker in Germany can produce in 4 days. The main issue here would be how this lax in productivity then impacts on wage growth. As showcased in the aggregate demand function, this can then have wider implications of the economy, especially onto growth in consumer spending which may be needed to increase job opportunities and further growth.

Moving on, the next section considered human capital before discussing wage structure. These two are directly linked; with education/ skills generally leading to higher wages. The basic idea behind this is that as workers acquire more skills/ capital they become more in-demand given the productivity that they can bring for a business. For instance, consider that a judge will be paid a higher wage than a bartender; which can be explained given (1) human capital development, and (2) how this impacts on the supply/ demand fundamentals for the specific job role. However, with this, it was also mentioned that the wage offered to the worker needs to be high enough to generate a positive utility, one which is higher than the utility offered by leisure time, in turn encouraging workers to work more hours.

From this, the chapter then moved into discussing unemployment. Whilst unemployment is classed as the number of people who are looking, and without a job, there are several reasons which split how we can distinguish unemployment. For instance, unemployment could be caused by regional economic disappearances, which in turn may cause structural unemployment. For example, it was mentioned that unemployment has been high in some Northern UK towns for several years given the decline of manufacturing and heavy industry. For the displaced workers, it may be difficult to find another job, especially if the job may require re-training, OR may offer them less benefits than the previous. There was also a mention that some unemployment could be hidden as workers leave the workforce. For instance, the U.S. has a much lower participation rate than the UK. If wages rose, and more opportunities became available, then the participation rate may increase.

1.8 Practical Example

This section will now provide an overview of labour in economics, providing some practical examples to explain theory. Like other goods, labour is considered as a supply/ demand function, with the economy seeking to reach an equilibrium point. Where demand/ supply intercepts would be the price, and so the wage rate offered to the worker. As with goods, if supply is greater than demand, then the wage rate will fall, however the difference in the labour market is that some countries have minimum wage legislation in place which restricts the wage rate falling too much.

To increase the prosperity of the country and drive economic growth, real wages need to increase. ‘Real’ is an important word as real wage growth would be seen as the wage growth after inflation is taken into account, rather than nominal wage growth which does not consider inflation. If real wages are increasing then living standards are increasing, in turn allowing consumers to increase their demand and spending. Aggregate demand can be considered with the following equation:

Aggregate Demand = Consumer Spending + Investment + Government Spending + (Exports - Imports)

As you can see, consumer spending is an integral part of economic activity. As well as being driven by productivity/ and so the business, the wage rate could also be dependent on the workers themselves, and their desire to work. With this in mind the neoclassical model can be considered:

What the above is saying is that the worker will look to maximise their utility between labour (L) and leisure (A). If the wage rate is too low, then some workers may consider to denote more time to leisure given that it offers a greater utility. As known, the main objective for an individual could be to maximise their own utility. On the other hand, as the wage rate increases too high, then a worker may start to denote more time to leisure given that the utility from this is higher than for the extra income which would be received. Taking this into account, this function can be visualised as a ….

Unemployment exists in all economies; some may be classed as natural unemployment and be seen as workers change jobs etc. Other unemployment may be structural, and caused by the decline of certain industries, be it manufacturing/ mining etc. While the economy may diversify, and provide jobs in other sectors, there may be barriers which restrict workers from changing jobs. For instance, consider how difficult it would be for a former coalminer in the North UK to move into an IT-related job. First and foremost, of the barrier of education/ training, with the worker’s current skillset un-transferable for a role in IT. There may be the need for further training which has the barriers of cost and time. This is where the government can potentially help, with a key focus of the welfare system in the UK being offering workers training to make them appeal to employers. However, even if the barrier of human capital is overcome, there is then the consideration of location. Regional unemployment is also an issue in the UK, with many commenting that UK economic growth has been centred on London. So, even if the worker did re-train for a role in IT, many of the jobs may be in London. With this, there would then be barriers to labour mobility, including the cost of the worker moving from the North UK into London as well as family ties etc. In some cases, there is then the consideration that some workers could leave the workforce, pushing down the participation rate, but in turn keeping the actual unemployment rate low.

To overcome these issues with unemployment, the government can make changes with policy. For instance, the government could provide financial incentives for businesses to locate within a certain area of the UK. This may allow for jobs to be created, creating a multiplier effect in the economy, leading to better economic prospects. For instance, the opening of a new manufacturing facility in the town may lead to more employment within the construction sector, the supply-chain, and the local service sector which will benefit from higher spending from the workers. Other ways in which the government can help would including greater training/ education facilities (as mentioned provided through the welfare system), as well as greater spending on infrastructure. For instance, consider the proposed HS2 development from the government which will bring high-speed rail to the UK and cut journey times between major cities London, Birmingham, Manchester etc. The benefit here is that it will increase mobility in the economy, increasing business activity. Similar is the ‘Crossrail’ project in London, reducing journey times into central London from surrounding boroughs. The benefit again is it increases labour mobility, making it easier to reach jobs available in central London. It also helps reduce some barriers to labour mobility; for example, the high cost of housing in London. Finally, it could also be mentioned that the government introduce regulation to improve labour standards, reduce discrimination and increase the ‘Utility’ gained from working. The main factor here would be the introduction of the minimum wage, more recently the National Living Wage in the UK. Increasing this makes to more attractive for those out of the labour force to work, increasing the participation in the economy. The major benefit behind this can be seen in the Solow Growth Model, which suggests that sustainable economic growth can only be reached by (1) and increase in the size of the labour force, or (2) increasing productivity. With UK productivity growth stalling, it would seem logical that the government seek to increase the participation rate to support economic growth.

Finally, the chapter considers collective bargaining, and the development of labour unions. For the worker, a labour union is beneficial as it allows for workers to bargain their benefits on a larger scale, giving them more power when it comes to negotiations. However, to businesses, labour unions can represent a barrier, restricting activities and adding to costs. Given this, it could be imagined that governments who prefer a free market about to labour-markets will seek to reduce the power of labour unions.

1.9 References & Bibliography

Sloane, P., Latreille, P., & O’Leary, N. (2013). Modern Labour Economics, London, Routledge.

Sloman, J., Norris, K., & Garrett, D. (2013). Principles of economics, London, Pearson Higher Education.

[1] Stands for Small to Medium Sized Enterprises

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: