Money, Banking & Interest Rates Lecture

1. The global financial system

The global financial system is comprised by a set of market-related institutions that includes financial markets, financial institutions, laws, procedures and regulations, as well as the set of techniques through which securities of all types of financial products and/or services are bought and sold (e.g., bonds, stocks, futures, options, and other hybrid securities are some of the most commonly exchanged financial products) (Mishkin, 2004).

1.1. The global financial system as a marketplace for the demand and supply of capital

The global financial system also encompasses sub-categories within financial markets, such as the money markets (where global interest rates such as the London Interbank Offered Rate, or LIBOR, are determined), and also multiple financial market segments where financial services are produced and delivered around the world (e.g., either in an offshore or offshore jurisdiction).

It could be argued that the financial system is one of the most fundamental products of modern societies, insofar as it reflects an interplay between the demand to financially service the needs of global financial consumers, taking into consideration the wider context of the financial markets’ role in providing for these needs with a specific range of financial products and/or services. That is, the financial markets are the meeting point of a given individual’s financial needs (when addressed within certain bounded and reasonable limits), as well as society’s ability to provide a similar or equivalent product or service. For example, in the credit markets, the need felt by an individual consumer to fund the purchase of her/his residential property through mortgage financing is met by the ability of a given financial institution to fund the said purchase through a specific mortgage product that the financial institution might offer within its product or service catalogue.

In essence, the financial system’s main task is to serve as a meeting point between the lending of scarce loanable funds from investors seeking a given rate of return, and the need to move the said loans to the hands of those investors interested in borrowing these amounts in order to buy goods and services, or to make investments in new equipment, facilities, or other productive assets. These asset purchases and/or investments typically foster investment schedules in order to help grow the economy, and expand the standard of living enjoyed by a given economy’s citizens. In the absence of the global financial system, and without the ability to allocate funds from lenders to borrowers, the significant diffusion of financial products and/or services would not be available to fully service the wide range of financial consumers at a global level. That is, without access to mass-market credit (from loans lent by banks to buy a house, to the availability of credit to fund specific consumer purchases), the structured pipeline of loanable funds the financial system provides would not be available, thus rendering our life in society much less enjoyable (from a strictly materialistic perspective, at least).

1.2. The global financial system and the occurrence of market failures: the importance of the credit channel

The financial system essentially determines both the cost/return and the quantity associated with the provision of funds between parties in the financial markets. This provision is also frequently associated with a given schedule of return and risk, which are typically associated with a given financial operation. These operations are an integral part of the millions of goods and services purchased every day through multiple markets, and whose payments indelibly pass through some payment gateway associated with a certain segment of the financial industry.

Nevertheless, it should be observed that financial markets are periodically prone to market failures, insofar as the events (however extreme) occurring within the financial industry might also have important repercussions on the overall health of the global economy. For example, the latest global financial crisis is an example of a market failure that compromised the major goals associated with the basic general mechanisms associated with the financial markets. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the credit channel became compromised due to the liquidity shock occurring in the global financial markets. Although the crisis originated in the U.S.A., the financial shock rapidly spread globally, affecting the performance of each and every segment of the financial markets, thus forcing monetary authorities to intervene. In sum, financial markets are thus also exposed to the occurrence of severe market failures that can strongly condition and impact the underlying real economies these markets are supposed to serve in ‘normal’ (i.e., non-crisis) times (Hull, 2009).

Discussion Point: But what is the link between the onset of a given financial shock and the subsequent impact on the underlying real economy?

1.3. The decentralisation of the global financial system

Furthermore, it should be observed that that are several types of financial markets within the highly decentralised structure of the global financial system. That is, within the global financial system, there are several specific markets that are bound by a particular set of financial operations that share common characteristics. These distinct types of markets may be characterised as quite structured channels through which a vast pipeline of loanable funds is continually transferred between those who supply funds to those who seek to use those funds to finance a set of economic activities to which capital financing is crucial. The ‘meeting point’ (i.e., the market equilibrium) between the demand and supply of loanable funds is thus the capital and interest rate earned by providers of available funds on the amount of capital lent, which is billed to those who seek to use the said capital for their economic activities. These specific financial market segments typically move a vast flow of loanable funds that continually replenish these specific segments. Some of the basic types of markets will be hereinafter described.

Definitions: The distinct segments of the financial markets that serve the global financial system may be classified in multiple forms. One of the most widely use definitional frameworks involves the distinction between the money markets vs. the capital markets (Mishkin, 2004). The former is mainly concerned with the supply of short-term loans with an average maturity of less than a year; while the capital markets are essentially concerned with supplying long-term possessing an average maturity superior to one year. A second major categorisation involves the distinction between open markets (where financial agents, either seeking or borrowing funds, may participate as buyer or seller), as opposed to the existence of negotiated markets (where only a few bidders seek to acquire assets, such as in the case of financial auctions) (Mishkin, 2004). A third major categorisation involves the definitional framework involving the primary versus secondary markets (Mishkin, 2004). The primary markets are mainly concerned with the issuance and promotion of newly minted financial instruments, whereas the secondary markets are essentially concerned with the trading activities involving existing financial instruments that have already been issued and initially traded in the corresponding financial marketplace. A fourth major categorisation involves the distinction between the spot markets and the futures, forward, or options markets (Hull, 2006). In the spot markets, financial products are typically exchanged through financial transactions associated with the immediate purchase/ sale of financial products or services. Whereas, in the futures, forward, or options markets (which by themselves deal in quite distinctive financial products or services), emphasis is put on the future delivery of the underlying products or services, at a mutually agreed date, and under certain market conditions.

1.4. The global financial system as the marketplace for savings and investment

Overall, it should be noted that the key role associated with a proper functioning of the global financial system is to harness an adequate pipeline of savings(i.e., capital available for lending purposes once personal consumption expenditures by households and the earnings retained by businesses are accounted for) and channel those funds into an adequate pool of investments (i.e., involving the purchase, by borrowers, of capital goods and/or the accumulation of inventories of products to sell) (Krugman, et al., 2011). Subsequently, investment in itself further stimulates the economy by generating new products and/ services, by creating new jobs, and by stimulating the establishment of new businesses, giving rise to further economic growth, job creation, and a higher standard of living. By virtue of the determination of interest rates within the global financial system, the money and capital markets increase the pipeline of savings generated by households and firms, augmenting the volume of new investment into new plant and equipment, and into inventories of products which become subsequently available for sale, in furtherance of the supply side of the markets.

Money thus becomes a vehicle for the satisfaction of the financial needs of both lenders and borrowers.

Need Help With Your Economics Essay?

If you need assistance with writing a economics essay, our professional essay writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Essay Writing Service can help today!

1.5. A brief definition of money

Prior to addressing the main determinants associated with the demand and supply for money, a brief definition of money should be presented. Money is a financial asset that can readily be used to purchase goods and services available in the marketplace. Broadly viewed, money encompasses a set of highly ‘liquid’ financial assets comprising cash, as well as other highly liquid assets (e.g., such as the monies easily available through checking accounts) (Mishkin, 2004). In the absence of money, the transaction of goods and services might have to be made through barter exchange (whereby a good would be sold in exchange for another good), which requires extensive ‘matching’ between the needs of buyers and sellers alike (Banerjee and Maskin, 1996). Money thus becomes the common denominator between the two parties involved in any transaction for goods and services, as it constitutes a common yardstick for both of these parties, eschewing the need for both buyers and sellers to match their needs through lengthy bargaining processes, thus avoiding cumbersome and otherwise lengthy exchange processes.

As with any other commodity, money is also subjected to the laws of demand and supply, insofar as the former is linked to the reasons why financial agents should hold this type of asset, while the latter is associated with the issuance of this type of asset by the relevant monetary authorities.

The following sub-section addresses the most pertinent aspects associated with the demand for money by financial agents.

2. The demand for money

The demand for money reflects the amount of financial assets associated with a high degree of liquidity that a given economic agent may want to hold. The main reasons for holding these positions are to be described hereinafter, but it should be pointed out that these positions are associated with a non-negligible economic cost (i.e., the opportunity cost for holding money).

2.1. The opportunity cost of holding money

This is due to the fact that, when a given financial agent opts to hold cash, this financial position carries a cost insofar as the said amount of money might be earning interest, but the economic agent has decided to forego that marginal income on the referred amount in order to use this position for some specific non-savings related purpose. For example, a given consumer may need to make a purchase requiring payment on demand. The said consumer might use the balance of her/his checking account to make that purchase, instead of using her/his accumulated savings. Notwithstanding, it should be observed that this decision is sensitive to the overall level of interest rates in place in the markets, as higher interest rates imply a higher cost of holding capital than when the rates at a lower level.

2.2. Reasons for holding money

Discussion point: But what are the reasons for holding money (regardless of the type of definition used)?

Economists have pointed out to the fact that economic agents might want to hold money due to three (3) different reasons (Mishkin, 2004). First, taking into consideration that economic agents need to use cash in order to settle frequent purchases of goods and services, these consumers might need to hold a sufficient amount of liquid assets in order to conduct these operations. That is, the economic agent needs to hold cash for transaction purposes. Second, economic agents might want to hold money to settle for uncertain events. That is, economic agents might face an uncertain situation that might require them to settle a purchase of goods and/or services, the amount of which is unbeknownst to them beforehand. Thus, these agents might opt to secure money in the event they might face this (uncertain) settlement, a motivation fuelled by liquidity purposes as a precautionary (i.e., pre-emptive) reason. Third, economic agents may want to hold liquid assets in order to rebalance her/his financial portfolios. In this specific case, economic agents might hold a portfolio comprising several types of securities (such as stocks, bonds, or hybrid securities), and holding money (e.g., cash) might alter the portfolio’s financial profile (e.g., in terms of risk and return) associated with the set of financial investment options. Thus, economic agents might be holding money due to portfolio rebalancing purposes, in order to adjust the composition of their financial portfolios to existing financial market conditions (e.g, as in the aftermath of a financial crisis, where financial positions have to be re-evaluated) (Mishkin, 2004).

Essentially, demand for money is established by either families (households) and/or firms, and might be viewed as the total sum associated with the three previous motives previously described (i.e., the transaction, the liquidity, and the portfolio rebalancing purposes). This does not exclude the fact that these motivations may vary over time, or that a given motivation might be more relevant than the remaining ones (the determinants of the corresponding empirical estimations are beyond the present guide).

Definitions: The Quantity Theory of Money states that the overall price level associated with the goods and services produced by a given economy is directly proportional to the amount of money in circulation (typically defined as the money supply). In numerical terms, the relationship is thus given by the equation of exchange:

M x V = P x Y,

where M represents the money supply, V the velocity of money, P the overall price level, and Y the aggregate income (P x Y is also known as total spending, or nominal GDP). A major implication associated with this theory is that inflation is essentially linked to the money supply, as both sides of the equation must balance (i.e., when M suddenly increases, both sides of the equation above must also increase, giving rise to inflation) (Mishkin, 2004).

Notwithstanding, their corresponding decisions about holding money are conditioned by multiple variables, such as the prevailing interest rate, income, and/or wealth, etc. One of the most important determinants for holding money is thus the level of interest rate, as economic agents and firms who hold money typically pay a price which is reflected in the opportunity cost of holding money (Krugman, et al., 2011). This opportunity cost is the foregone interest rate that could be obtained should the said money be earning interest. That is, the opportunity cost for holding money is reflected in the lost interest when the money is not used as a saving instrument over time. Notwithstanding, it should be observed that the higher the overall level of interest rates, the higher the opportunity cost (which is foregone) associated with the option of holding money.

2.3. The demand for money curve

A demand for money schedule can thus described, using the overall level of interest rates as a main determinant. Because the overall level of interest rates typically conditions the opportunity cost of holding money, the overall quantity of money economic agents and businesses might want to hold is, other things being held constant, negatively related to the interest rate.

Where the importance of demand for money is concerned, this topic is of the utmost importance to macroeconomic policy analysts, insofar as estimating the demand for money plays a pivotal role in the pursuit and implementation of appropriate monetary policy tools, and in the selection of appropriate monetary policy actions. This is especially relevant in the context of the onset of economic and/or financial crises, which necessarily prompt the intervention of the relevant monetary authorities in the aftermath thereof (Mishkin, 2009). Thus it is vital for these policy analysts to have estimations regarding this important macroeconomic topic, in order to facilitate their interventions in the appropriate markets (e.g., in the monetary markets). As a consequence, both empirical and theoretical research has been devoted on this topic.

A simple curve depicting this relationship between money and interest rate can be drawn based on the negative association between these variables. Accordingly, the curve representing the money demand curve depicts the negative relationship between the interest rate offered by the financial markets and the quantity of money demanded by economic agents. The curve thus has a negative slope, insofar as a higher level of interest rates offered by the market is associated with a higher opportunity cost related to holding money. That is, a higher interest rate also reduces the overall quantity of money demanded by economic agents (Krugman, et al., 2009).

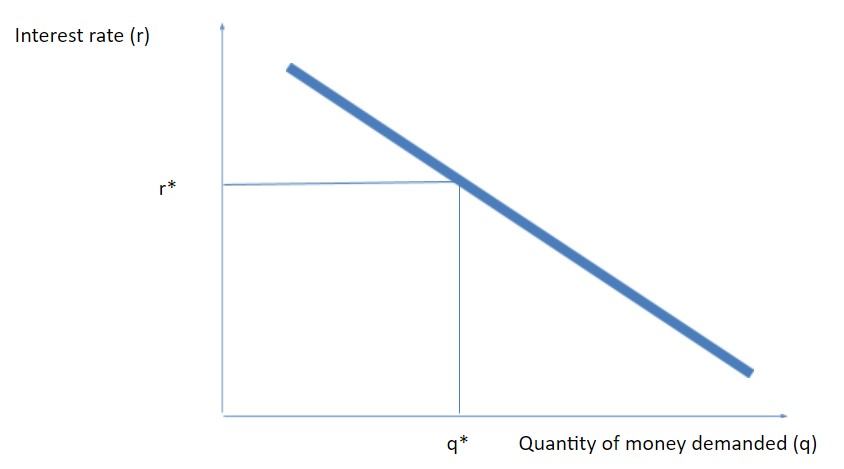

Thus, a typical representation is presented in the following figure:

FIGURE 1. THE MONEY DEMAND CURVE

As can be observed in this figure, the higher the overall level of interest rates, the lower the quantity of money demanded, as economic agents prefer to hold more money in savings, than to have it readily available and forego the corresponding interest earned.

2.4. Shifts in the money curve

Nevertheless, it should be observed that certain economic circumstances may dictate that the demand for money curve might shift over time. This is an important point to retain, especially in the context of the influence of other unaccounted variables over the said negative relationship between interest rates and the quantity of money demanded.

Accordingly, a change in the demand for money may occur when there are changes in the aggregate price level, or in real GDP, or even within the banking industry and the corresponding technology it promotes. For example, the ubiquity of ATM machines and pay terminals for debit cards may strongly curtail the need to physically hold cash in order to pay for purchases, as transactions might be conducted solely using electronic means of payment, thus affecting the amount of money demanded.

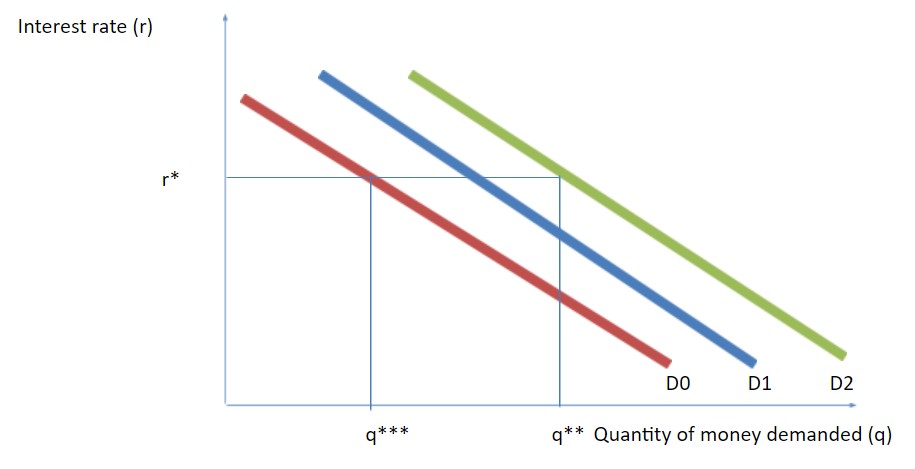

FIGURE 2. THE MONEY DEMAND CURVE AND CORRESPONDING CURVE SHIFTS

When economic agents demand more money, the corresponding money demand curve shifts to the right (D1 to D2), and the quantity of money demanded rises for any given interest rate. Reciprocally, when economic agents demand less money, the corresponding money demand curve shifts to the left (from D1 to D0) for any given level of interest rate, as the quantity of money demanded falls for any given level of the interest rate.

Lastly, the following section will deal with the supply for money side of the economic equation, insofar as the demand for money schedule is obviously constrained by the availability of the several concepts that might be associated with money (bank notes, coins, etc.).

3. The supply of money

The money supply is essentially defined as a set of liquid and safe set of assets that businesses and households and businesses can use in order to make their payments, or even to use as a financial instrument for short-term investments. For example, the U.K.’s currency (£) and corresponding balances held in checking accounts and/or money savings accounts are typically included in many of the most basic measures associated with the money supply (Sloman, 2006). Notwithstanding, there are multiple technical monetary measures associated with the money supply. For example, there are several standard (i.e., universally accepted) measures of the money supply that reflect these type of assets. Amongst others, these measures include, for example, the monetary base, as well as the monetary aggregates such as M1 and M2.

Types of money

Definitions: The monetary base is essentially defined as the sum of a given economy’s currency in circulation and the balances associated with the deposits held by banks and other depository and financial institutions in their corresponding accounts located at the corresponding central bank (Krugman, et al. 2011). In turn, M1 is defined as the sum of currency in circulation held by the public and the deposits at depository institutions. The latter are financial institutions that accept funds essentially through deposits from the general public, and might encompass commercial banks, retail banks, savings banks, or even building societies. M2 is further defined as M1 plus the savings deposits, as well as other safe and liquid assets, including some money market funds (Federal Reserve Bank, 2016).

Typically, these concepts of money are quite well documented by a given economy’s central bank, and information on the existing categories is quite readily available. This is in stark contrast to the information concerning the money demand (and the corresponding curve), which has to be estimated using advanced mathematical techniques of econometric extraction, as information on the distinct components of the money demand curve is not easily observed. Another important contrast to the demand for money framework is associated with the fact that the money supply framework is essentially determined by financial institutions, such as the central bank or other financial institutions concerned with the process of ‘money creation’. In fact, under the money supply curve, the most important agents are the following: i) the economy’s central bank (i.e., the government agency that oversees the whole banking system and is responsible for the conduct and proper implementation of monetary policy (e.g., the Bank of England); ii) the banks(e.g. retail banks, as the financial intermediaries that collect deposits from businesses and individuals and subsequently provide commercial or individual loans); iii) depositors (e.g., the individuals and businesses that hold deposits in financial institutions; and iv) borrowers from banks (e.g., individuals and businesses that borrow from the lending financial institutions).

3.1. The ‘creation’ of money: the institutions

In essence, money is not only created by the central banks (e.g., the coins and notes in circulation), but is also ‘created’ through the concession of credit by financial institutions that are willing to take depositors’ monies and ‘farm’ them out to borrowers that will subsequently apply these funds for productive- or personal consumption-related investments and assets. The borrowers can then pay the initial capital plus the accrued interested to the financial institutions involved as the money lenders, and these proceeds can then cover the financial institutions’ obligations towards their financing sources (e.g., deposit holders).

In the past, the most common measures associated with the money supply had exhibited close relationships with a given country’s most important economic variables, such as the nominal gross domestic product (GDP), or the price level. That is, these measures were actively used as monetary policy instruments in order to attain certain macroeconomic goals established under a given central bank’s mandate (e.g., low inflation, sustainable economic growth trajectories, etc.). Notwithstanding, in more recent times, these correlations have broken down, so that the evolution of the money supply is no longer a good harbinger of the evolution of the GDP, although the link between some more evolved monetary aggregates (such as M2) and inflation might still observable in certain economies.

The most important financial institution in the money supply side is thus the central bank, but banking institutions also play an important part in the ‘creation’ of money. For example, banks can create money through their financial intermediation function. Banks elicit financial assets such as cash and other liquid assets from deposits holders, and subsequently ‘farm’ this money out to those seeking business and/or consumer loans. These activities are for-profit banking activities conducted in order to generate revenues and profits for these financial market participants.

3.2. The creation of money: the process and the credit multiplier

In order to initiate the process of money creation, central banks typically deal with each financial institution (banks) under their supervision, generally through a specific type of financial account. When central banks wish to deal with the financial institutions under their supervision, they typically conduct open market operations by buying/selling securities (e.g., bonds) to banks. When central banks buy bonds, they inject liquidity (i.e., money) in the banks and into the financial system in the form of deposits. Quite the contrary, when they sell bonds, they typically withdraw liquidity from banks and the financial system through the said account. Banks thus receive or support financing through this special relationship with their corresponding central bank. In an expansionary monetary phase, that is, when central banks want to stimulate economic growth by facilitating the concession of credit by banks, they tend to buy securities from banks, thus injecting liquidity into the financial system through a specific set of banks. In turn, banks can subsequently use these deposits to the benefit of credit concession to their corresponding clients. That is, banks constitute a very important financial intermediary in the credit concession channel, insofar as they are the recipient of funds from central banks, and are thus in a position to lend those funds to their retail client base. However, a small portion of these deposits is retained by the financial institution in order to guarantee the said bank’s solvability, while the remaining funds (essentially, the bulk) are lent. In turn, when the monies lent are, for example, applied in a given investment project, these funds not only stimulate economic growth (as investment is a fundamental determinant of GDP), but these monies are then deposited at another financial institution by these funds’ recipients. The money creation process thus continues at this second bank (and the funds, minus the required reserves, are lent for another entirely different purpose). This is the essence of an expansion of the money supply, as the process continues indefinitely, although the multiplier effect decreases with each round. Expansion of the money supply thus stimulates the underlying real economy, as well as the banking activities associated with these financial activities. Lastly, when monetary policy becomes contractionary, that is, when central banks wish to cool an ‘overheating’ economy (because it leads to excessive inflation, for example), they pursue the opposite macroeconomic policy by systematically selling securities in open market operations, and withdrawing monies from banks and the financial system as a whole. In this scenario, there is a contraction of the money supply (Mishkin, 2004).

3.3. The money supply curve

Overall, it should be observed that the money supply process is not very sensitive to the overall level of interest rates. Taking into consideration that the money supply essentially encompasses the currency in circulation and liquid bank deposits, the said money supply is not deemed to respond to the overall level of interest rates. In this case, the money supply is the same whether interest rates are low or high, suggesting that the money supply curve is the same for each and every level of interest rates. The following figure is typical of the money supply curve:

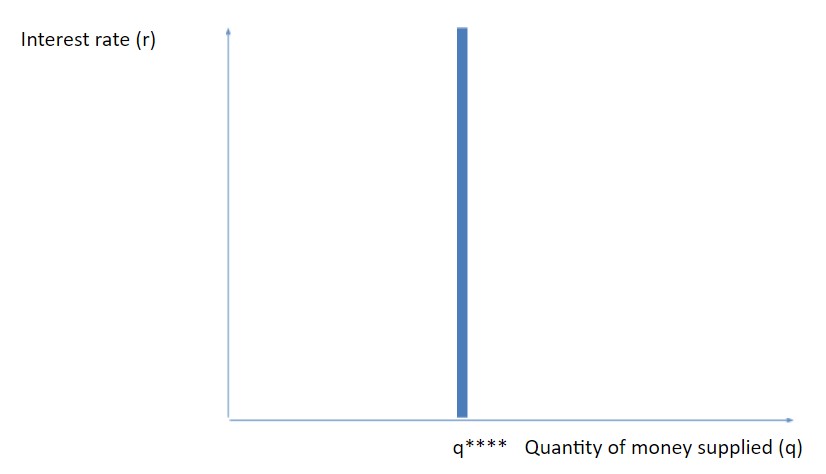

FIGURE 3. THE MONEY SUPPLY CURVE

This above-mentioned figure depicts the money supply curve, which is insensitive to the overall level of interest rates. That is, the money supply is typically the same regardless of the level of interest rates prevailing in the economy. The quantity of the money supply is thus established at q****.

4. The market equilibrium between the demand and supply of money

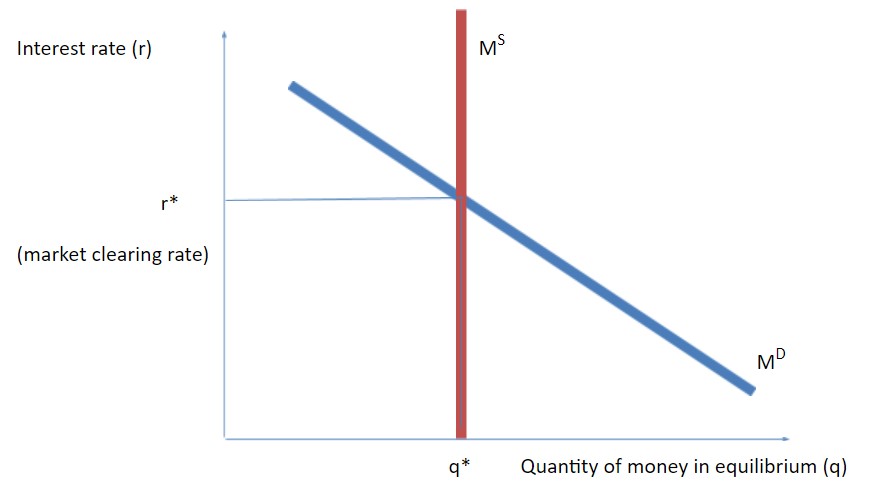

In any market where demand and supply meet, a market equilibrium ensues determining the overall quantity of goods (in the present case, the amount of money), as well as the corresponding price (in this case, the overall level of interest rates). This is the essence of the market clearing mechanism whereby the two sides of the market are confronted in order to arrive at a satisfactory solution to both parties - the equilibrium level. Typically, this equilibrium point satisfies both sides of the market through a bargaining process. The following figure depicts the overall market clearing mechanism and the ensuing market equilibrium.

FIGURE 4. THE DEMAND AND SUPPLY FOR MONEY: THE MARKET EQUILIBRIUM

4.1. The equilibrium between demand and supply

The market clearing mechanism thus confronts both the money demand curve and the money supply curve. The money demand curve represents the segment of economic agents that require money for a number of motives, while the money supply curve depicts the overall level of currency and deposits available, as issued by the central bank, as well as through financial institutions that participate in the money creation process within the financial system.

The equilibrium point is thus attained through the intersection of the demand and supply curves at (r*,q*). It should be observed that this is a unique point. Should the market interest rate be above r*, the money demand curve would suggest a demand for money lower that q*. In this case, the supply of money would still be q* (higher than the demanded quantity). Given that there would be excess liquidity in the system (as the money demanded would be lower than the supplied), the interest rate would fall until r* was reached, matching demand and supply. The market would then clear at (r*,q*).

On the other hand, should the market interest rate be above r*, the money demand curve would suggest a demand for money higher that q*. In this case, the supply of money would still be q* (lower than the demanded quantity). Given that there would be a liquidity shortage in the system (as the money demanded would be higher than the supplied), the interest rate would rise until r* was reached. The market would again then clear at (r*,q*), matching demand and supply.

4.2. Changes in the equilibrium through the money supply

Lastly, it should be observed that monetary policy might be either expansionary or contractionary. Where expansionary monetary policy is concerned, the central bank seeks to expand economic growth by expanding the money supply through, for example, open market operation. This necessarily expands the money supply curve (to the right, in the above-mentioned figure), lowering interest rates and stimulating the economy. Reciprocally, where contractionary monetary policy is concerned, the central bank seeks to contract excessive economic growth (which might lead to higher inflation) by contracting the money supply through, for example, open market operations. This necessarily contracts the money supply curve (to the left, in the above-mentioned figure), raising interest rates and cooling off the economy (Samuelson and Nordhaus, 2009). The above-mentioned reasoning assumes that the demand for money stays constant in both cases. Notwithstanding, the central bank thus becomes a major decision maker in the financial markets, in view of the fact that its actions can swiftly condition the performance of the financial markets through the manipulation of the overall level of interest rates. This central bank intervention is particularly important in the context of the fulfillment of the central bank’s mandate, as the interest rate instrument has become a decisive tool in the central banking toolkit.

Need Help With Your Economics Essay?

If you need assistance with writing a economics essay, our professional essay writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Essay Writing Service can help today!

REFERENCES

Banerjee, A.V., and Maskin, E.S., 1996. A Walrasian Theory of Money and Barter. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. CXI, (Issue 4), pp. 955-1005.

Bank of Mingo, 2016. Bank of Mingo. [Online]. Bank of Mingo. [viewed 15 October 2016]. Available: https://www.thebankofmingo.com/

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2015. What is the money supply? Is it important? [Online]. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System [viewed 15 October 2016]. Available from: https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/money_12845.htm

Gambacorta, L., and Marques-Ibanez, D., 2011. The bank lending channel: Lessons from the crisis. [Online]. Available: http://www.bis.org/publ/work345.pdf [viewed 15 October 2016].

Hull, J., 2006. Options, Futures and Other Derivatives. Sixth Edition. United States of America: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hull, J.C., 2009. The Credit Crunch of 2007: What Went Wrong? Why? What Lessons Can Be Learned? [Online]. Available: http://www-2.rotman.utoronto.ca/~hull/downloadablepublications/CreditCrunch.pdf [viewed 15 October 2016].

Krugman, P., Wells, R., and Graddy, K., 2011. Essentials of Economics. Second edition. United States of America: Worth Publishers.

Mishkin, F.S., 2004. The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets. Seventh edition. United States of America: Pearson.

Mishkin, F.S., 2009. Is monetary policy effective during financial crises? Available: http://www.nber.org/papers/w14678.pdf [viewed 15 October 2016].

Samuelson, P.A., and Nordhaus, W.D., 2009. Economics. Nineteenth edition. Asia: McGraw-Hill Education.

Sloman, J., 2006. Economics. Sixth edition. England: Pearson Education Limited.

CASE STUDY

We are presently living in a post-recessionary economic environment, after having gone through one of the worst global financial crisis the world has ever known. Moreover, the said crisis’ global impact has attained truly pandemic proportions, as its consequences will be undoubtedly felt throughout the following years. The crisis’ impact was compounded by three major banking failures, namely, Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, and Northern Rock. The first two banking failures constituted a direct consequence of the ‘Subprime’ financial crisis in the U.S.A., especially in the context of the demise of the subprime segments in this country, as well as the failure in the U.S. money markets; lastly, Northern Rock was a significant U.K. banking demise associated with the global collapse in property prices in the U.K. and international financial contagion processes in the global banking industry.

Bear Stearns

This U.S. financial institution was a major brokerage firm, investment bank, and securities trader that operated at a truly global scale. Prior to its demise, the bank had been active in the financial markets for more than 85 years. Before the onset of the U.S. Subprime crisis, the bank had a massive financial position in subprime mortgages (excessive residential credit held in its balance sheet). Most obviously, the bank’s stakeholders (its clients, counterparties, and investors) started to raise serious questions concerning the state of the bank’s balance sheet and the real quality of its financial assets. In 2007, when a failed hedge fund sponsored by a subsidiary of Bear Stearns brought about unwanted questions about the quality of the subprime loans the bank held, the bank’s stock market price started to collapse, in line with the retraction in U.S. house prices. Moreover, the bank had a reputation as an aggressive trading institution quite willing to undertake significant risks, and the firm was quite proud of its reputation as a top bank, with a stellar management team, as well as good management practices. The bank was recognized as one of the market leaders operating in its segment, especially in the run-up to the crisis from 2005 to 2007. Notwithstanding, and due to the massive scale of its subprime business, the bank became one of the most highly leveraged financial institutions on Wall Street. The bank collapsed in March 2008, and was later sold to JPMorgan. The bank’s demise constituted a key moment in the financial watershed that ensued, especially taking into consideration the weaknesses of risk management procedures in the financial industry that ultimately led to the global financial crisis and ensuing recession (Ryback, n.d.).

Lehman Brothers

This U.S. financial institution was a financial giant with more than 209 registered subsidiaries in twenty-one countries (Fleming and Sarkar, 2014). This giant financial conglomerate filed for bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, while its subsidiaries also started to collapse in the wake of the initial U.S. bankruptcy.

Central to the Bank’s demises was the Bank’s ‘Repo 105’ program, which transformed a financing transaction mechanism into a massive asset disposal mechanism. In a typical repo operation (which stand for ‘sale and repossession’), a given financial institution borrows funds against highly liquid securities (usually treasuries), so that the latter are used as collateral. For example, if a bank has securities for £105, it might borrow £100 from another financial institution, by presenting the securities as collateral for the short term loan. The £5 difference between the value of the posted collateral and the loan is called the ‘haircut’, and constitutes the price for both the liquidity of the security and subsequent risk attached to the financing operation. Loans in the repo markets are typically short-term, lasting from one night to three months. Lehman Brothers allegedly used repos for financing reasons, but accounted for these operations as asset disposals, so that the Bank effectively used the repo proceeds to decrease its leverage (at least officially), thus avoiding any regulatory scrutiny that would otherwise be required. This ultimately led to the Lehman’s demise. The Bank extensively used this short-term financing model, in order to fund its multi-billion dollar operations in aggressive real estate-related assets. The Bank thus collapsed under its significant exposures to subprime mortgages, in the wake of the real estate collapse of 2007-2008 (IMD, 2010).

Northern Rock

In September 2007, the U.K. witnessed its first bank run in more than a century, as deposit holders of Northern Rock patiently waited in line outside the Bank’s branch offices to withdraw their money. Northern Rock’s collapse stemmed from the fact that the Bank relied heavily on non-retail funding, through a complex combination of short-term financing in the capital markets, and through securitized notes and other longer-term funding sources. Northern Rock used this financing mechanism in order to fund the expansion of its balance sheet acquisition of mortgage assets, which overwhelmingly outgrew the Bank’s traditional funding source of branch-based retail deposits. On the eve of its demise, Northern Rock - a building society that should have heavily relied on mutually owned savings and the Bank’s mortgage business and clients - had a coverage of liabilities to retail deposits in the vicinity of 23 percent (as a % of total liabilities). In the summer of 2007, this ratio degraded even more considerably, especially after the bank run by the deposit holders. Although Northern Rock had virtually no subprime lending of its own (the Bank was essentially in the business of prime mortgage lending to U.K. households), it was nevertheless tapped on financing mechanisms that heavily relied on short-term funding processes (quite a similar situation to Northern Rock’s counterparts in the U.S., as these institutions were quite heavily exposed to the subprime debacle). In the summer of 2007, when the global short-term funding and interbank lending markets all but froze, Northern Rock’s financing model suddenly collapsed. The quality of the balance sheet of any mortgage bank is vulnerable to a sharp decline in house prices and rising unemployment, insofar as it heavily affects the quality of its banking assets, as well as its balance sheet, especially once an economic and financial shock occurs. Although the Bank of England tried to step in in order to save the bank, Northern Rock ultimately collapsed, and was placed under public ownership in 2008 (Shin, 2009).

References (Case Study)

Fleming, M.J., and Sarkar, A., 2014. The Failure Resolution of Lehman Brothers. [Online]. Available: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/2014/1412flem.pdf [viewed 15 October 2016].

IMD, 2010. The Lehman Brothers Case - a corporate governance failure, not a failure of financial markets. [Online]. Available: http://www.imd.org/research/challenges/upload/TC039-10PDF.pdf [viewed 15 October 2016].

Ryback, W., n.d. Case study on Bear Stearns. [Online]. Available: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/FINANCIALSECTOR/Resources/02BearStearnsCaseStudy.pdf [viewed 15 October 2016].

Shin, H.S., 2009. Reflections on Northern Rock: The Bank Run that Heralded the Global Financial Crisis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 23 (Number 1), pp. 101-119.

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: