Types of Assessment Lecture

Introduction

This chapter addresses the topic of assessment. The first section introduces the concept, and offers key definitions of terms related to assessment practices, as well as underlining the centrality of assessment to any planned programme of instruction. The second section builds upon this, and explores the reasons why assessment is important to teaching and learning, as well as why a full consideration of the assessment-related aspects of any topic are of crucial importance to planning successful delivery, both at the level of the individual session, and over the entire programme of instruction. The importance of an 'assessment for learning' approach is privileged here.

The third and final substantive section of the chapter itemises assessment methods and indicates their relative strengths and weaknesses. As the chapter will show, assessment is a complex subject area within educational inquiry in its own right, and one which deserves a full and thoughtful consideration. To support your work on assessment, each chapter section is paired with a reflective element which challenges you to reappraise your incoming perceptions of the topic area, as well as to draw fresh lessons from your own experiences as an assessed learner in your own right.

Learning objectives for this chapter

By the end of this chapter, we would like you:

- To be able to define assessment

- To appreciate the centrality of why assessment is important to learning

- To be able to consider the relevance of an assessment for learning approach

- To be able to consider the usability of multiple assessment methods

- To be able to select appropriate assessment methodologies

Get Help With Your Education Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional education essay writing service is here to help!

What is assessment?

Assessment is a key part of any educative experience. To some extent, at least, the element which distinguishes education from other aspects of learning is the presence of assessment. As this chapter will show, assessment can take many forms, and the creative and proactive teacher should be prepared to draw upon a diverse range of methods and approaches to assessment in order to get the best from their learners.

Assessment does not have a single function. Though it may be tempting to conceptualise assessment as an end-of-course activity intended to gauge learners' abilities with reference to the course which has just been completed, this and the following sections will demonstrate that assessment is varied, multi-purpose, and may be enacted using a perhaps surprisingly diverse array of methods.

While there may be the core aim of checking the level and extent of learning which has taken place, considerate assessment can also motivate and inspire leaners to engage and to achieve, while providing a mechanism by which learning can be validated and rewarded. Assessment and its feedback protocols, from informal praise to the formal grading and certification of GCSE qualification coursework, can also offer guidance and direction, allowing learners to assess their progress for themselves, as well as offer refocusing on areas which require more attention.

In bald terms, assessment may be formative or summative. Formative assessment is that which a learner receives and which an educator gives throughout a course; formative assessment allows both parties to better understand the level and success of learning thus far in the course, and provokes in turn reflection on and an opportunity for guidance for both rewarding good work and targeting deficiencies and other areas in which evidence of learning might be better produced. Summative assessment, sometimes called final assessment, refers to the end-of-course assessment opportunities intended to make a final determination of the learner's success over the entire course. Some courses may also have initial assessments, which are intended to be diagnostic; these are a kind of formative assessment, and may be used to target support or otherwise assess the suitability of a prospective student for the proposed new course of instruction. In the UK educational system, formal qualifications often act in part as both summative and formative qualifications, as they not only offer an award for successful completion of an earlier course at a given level, but are taken as evidence towards suitability for successor qualifications. The pathway from GCSE to A level, and from A level to undergraduate study, exemplifies such a progression.

Assessment is both regular and continual, though it may not be always formal. Responses to learners' questions, and praise and guidance given in passing, are examples of informal assessment and feedback. Feedback, whether written, oral, or in the form of grades or scores without commentary, should always be geared towards being constructive, as feedback which does not seek to develop the learner can be counterproductive and may impact negatively on their confidence. Assessment and feedback which is constructive is more likely to give confidence, to inspire improvement, to give guidance on areas of the topic requiring a closer focus, and will reward achievement (Gravells, 2015).

Assessments may be internally or externally set. For certificated qualifications, externally set assessments will be part of the design of the course of instruction, with a mix of coursework assessment and final assessment contributing to the overall determination of the candidate's level of competence in the subject as the level being assessed. The final grade awarded in such situations is not merely the assessment result, but also acts as a form of feedback. Assessment arrangements will be clearly described in the qualification rubric, and should be taken into consideration in the scheme of work and lesson planning devised so that learners will be more than sufficiently prepared not only in the subject knowledge and related competencies which the course is privileging, but also in the modes of assessment which are favoured in the qualification, and particularly in its final assessments. Though teaching to the assessment is to be guarded against, as it favours assessment performance over subject knowledge, teaching nevertheless needs to prepare learners for assessment in relevant ways. The precise direction taken towards the final assessment goal is in the individual teacher's hands; the level and extent to which a balance between developing learner competencies and being assured of their preparedness for assessment is one of the marks of a skilled classroom practitioner.

Internally set assessments tend to the developmental, and are devised by the teacher with reference to the course materials in order to evidence engagement with the subject, to reinforce and demonstrate acquired knowledge, and to give opportunities to apply new learning. Think of all activities and tasks which are not focused towards input as being assessment-related. To some extent, all interactions which you may have in the classroom have a relationship to assessment. As teachers, we are continually making judgments about the level and extent of learner engagement with their subject, and are giving developmental feedback on an ongoing basis as a result of this.

All assessment, then, should be geared towards learning. The phrase 'assessment for learning' captures this impetus; there has been a shift in recent years away from defining assessment solely in relation to summative ability, and more towards assessment being seen as part of an ongoing set of learner developmental processes. If assessment does not benefit the learner, then perhaps we should question why that assessment exists (Berry, 2008).

Reflection

In what ways have you been assessed in the past? And in what contexts? Were those assessments formal or informal? Were ou ever assessed in such a way that you did not feel as though you were being tested?

Were the links between what you were learning and how you were expected to demonstrate what you had learned clear to you?

How do you feel as a learner if you are set assessment tasks which feel irrelevant?

Has a piece of feedback ever changed your approach to a topic? If so, how?

Why is assessment important?

This section develops the investigation as a topic area and has two main parts. The first considers in more detail the reasons why assessment is important; the second part looks at the contribution which assessment for learning can make, and why this reconceptualization of assessment has become a dominant force in the ways in which assessment is articulated in the contemporary classroom.

Assessment can be said to have four main functions; these are not wholly separate categories, but may overlap, depending on the context of the assessment. The first function is that of placing and selection: initial assessments to band learners according to incoming ability, or used as an entry qualification. The second, and perhaps a related aspect of assessment, is diagnostics: assessment may be used to determine if (and the nature and extent of) a specific learning difficulty is present, so that support may be targeted towards the learner's precise requirements. The third function is that of accountability. Assessments may be used to provide a determination of whether learning outcomes have been achieved, either in part (as in formative assessment) or in full (as in summative modes of assessment). In addition, learner grades are used as a measure of both individual teachers' and whole schools' ability to help learners towards those same learning outcomes. Such data is informative at a school and local authority level, and regarding league tables and internal quality processes, as well as to external Ofsted inspections. Accountability measures in UK compulsory education include Progress 8 and Attainment 8, which derive information and standings from GCSE level performance, and so give an indication of the effectiveness of school performance at Key Stage 4 (HM Government, 2014). The fourth function of assessment is that of supporting learning. Within this overall category are aspects, such as the development of learner motivation and the building of confidence by recognising and rewarding achievement, the providing of data to teachers so that they can direct support to where it is needed, and to assure them of the nature and extent of whole-class and individual learner engagement with learning (Brown, Fautley, and Savage, 2008).

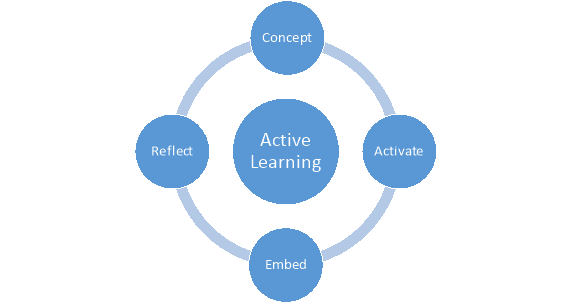

Assessment for learning is often discussed in relation to the learning cycle. Though there are variations to the cycle, Diagram 1 below offers perhaps the most commonly-held version, where learning is conceived of as a process. The concepts being learned are in turn introduced, activated, embedded and then reflected upon; this can then be developed in a cyclic fashion and the core idea returned to in more detail.

Diagram 1: the learning cycle

Assessment may be used at each point in the cycle to determine the extent of pre-existing knowledge of the concept being introduced, to gauge learner comfort with the concept in application in the activation and embedding stages, and then as a summative activity in the reflection stage, before either moving on to a fresh concept, or revisiting it in more detail. Throughout, assessment is being used as in support of learning, and of distinct elements of the learning cycle, rather than as an end in itself. In such ways, assessment is part of teaching and learning, and not distinct from it.

Though assessment for learning is often formative, the two terms are not wholly interchangeable; the latter may also refer to any non-summative assessment method, whereas assessment for learning is that which contributes to the learner understanding of and engagement with the topic area being studied. For Young (2006), assessment for learning is important as it articulates four important characteristics. These are: having high quality learner-teacher interactions; the sharing of clear and mutually-understood learning goals; the closing of the learning gap between learners producing work and their receiving feedback on it; supporting learners to be responsible for their own learning.

An interactive classroom - not merely in the sense of using ICT to support learning, though this may be involved - allows for high-quality and meaningful engagements between teacher and pupil, and between learners as peers supporting each other. The flow of question and answer, and activity and meaningful initial and immediate feedback to assessment opportunities helps foster an environment where learning can progress through results and achievement, and where support can be targeted and given in productive ways.

Where learning is purposive - from the establishment of clear session aims and objectives to there being a mutually understood rationale for and relationship between input and activities which have an assessment component - then learning is productive. The use-value of knowledge is made clearer, and both learners and educators can assess progress made and the clarity of connections being produced by learners in their application of skills and relevant concepts (Young, 2006).

Where assessments are linked directly to feedback, and particularly in the time gap between the two, learning can be consolidated in the moment rather than being lost in the space between assessed work being completed and being returned once marked. Online activities and homework systems can be of use here, though immediate oral feedback can be of use in clarifying the connections between study and assessment. Developmental suggestions in feedback are useful; this reinforces the idea that assessment is learning and is productive, rather than being a summative activity which need not be returned to.

Where learners are motivated in their own learning progress, and in becoming responsible for their development, use can be made of that investment. One possible way of encouraging this is using peer assessment where learners can be encouraged to derive insights into their own performance by grading and assessing that of their peers. Elsewhere, a strategy is for the teacher to model behaviour for learners to adopt for themselves in better assessing their own learning capabilities and in planning their own approaches to their learning, and their evidencing through assessment of that engagement (Wiliam, 2009).

Reflection

Do the four functions of assessment given above make sense to you? Are there any other functions that you can think of?

Look again at the learning cycle. Are you clear on how you can make assessment a part of learning as opposed to something distinct from it?

Does the 'assessment for learning' approach make sense to you? In what ways? Are there ways in which you prefer to see a division between learning and assessment? If so. What are your reasons?

Get Help With Your Education Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional education essay writing service is here to help!

Types of assessment

This section outlines different types of assessment, and makes brief comments on their relative strengths and weaknesses. Not all assessment types will be suitable for all contexts, so this is very much a guide to the diversity of possible approaches than a list to be followed in all teaching circumstances. Neither is this listing intended to be wholly comprehensive; the range and applicability of potential types of assessment is a subject which could (and does) fill entire books. Nevertheless, the selection offered here may give ideas for assessment approaches of your own to adopt.

Accreditation of prior learning (APL)

Assesses prior learning to give learners credit for achievements and learning already completed. This is useful for avoiding duplication, particularly in adult and/or vocational contexts. However, it requires checking, and thorough and detailed record-keeping, which can be time-consuming.

Assignment

A catch-all term to describe practical or theoretical written tasks; may be (though does not have to be) essay or report based in structure. Advantages include the opportunity for the learner to express themselves, often in detail. Marking guidelines may be set by external organisations. However, grading and feedback can be time consuming, though offers the potential for detailed responses.

Blended assessment

Blended learning and assessing most often takes a multimedia approach, and typically integrates online and offline activities. Can be popular with learners, and addresses a spectrum of learning styles through the broad approach. Equal access to ICT may be an issue though.

Case study

A case study replicates a real-world scenario in a usually fictionalised context. Case studies allow learners to safely apply learning to realistic conditions, which can incentivise engagement. Detailed case studies can be lengthy and time-consuming to assess; group work needs to be apportioned fairly, so that individual learners' contributions can be detected (Klenowski and Wyatt-Smith, 2013).

Discussion/debate

A classroom discussion can be ad-hoc, extemporise, or learners may be required to prepare in advance. This can allow for group work, participation by all, and can facilitate free discussion and debate. However, careful leadership is needed to ensure that debates stay on-topic and under control. Learner feedback can, though, be immediate, and peer assessment is possible.

Essays and reports

Formal written pieces in response to a specific (and usually set) question; useful for academic topics and for exploring subjects and argumentative skills in depth, as well as providing evidence of language and research skills. Essays are less suitable for younger and less able learners, and can be time-consuming to read and grade. Safeguards may need to be in place to guard against plagiarism.

Examinations

Formally-conducted tests under observation conditions. Exams are good for assessing summative knowledge, and in working against time pressure and resource constraints. They can be stressful for learners, though, and require resources to stage. Feedback can be time-consuming to arrange.

Group work

Activity-based work, which may take any of a variety of forms, though a key aim is the assessment of the group working as much as the product of that work. This type of assessment encourages peer assessment, co-operation, and can make lengthy tasks manageable in classroom contexts. Issues of personality clashes, equal workload sharing, and of the potential for disagreements between group members over the way to approach the task may arise, though, and require considered marshalling by the teacher (Clarke, 2014).

Homework

An overarching term for work set to be completed outside timetabled sessions. Homework must be meaningful and extend learning; it should not be for catching up on uncompleted classroom work. One useful way of having homework address learning is for it to be preparatory for the next session. Homework assessment should be timely and individualised to the learner. Excessive assessed homework is time-consuming for learners and teachers.

Journals

Learners keep an ongoing diary of progress and reflections related to an aspect of their studies. Journaling can develop self-awareness and ownership of learning, as well as stimulate personal opinions. Confidentiality must be assured, though, and assessment can be difficult because of the subjective nature of the responses (Bartlett, 2015).

Observation

Learners being observed in class, or performing a skill allows live evidence to be captured (and perhaps recorded for later analysis) as well as validates achievement through the successful demonstration of the competencies under consideration. Some feedback may be possible immediately, if the observation is conducted in-class.

Peer assessment

Learners grading or offering opinions on others work can stimulate group and class engagement, and can offer immediate feedback. Simple methods can involve cross-marking of papers in class. Personality issues may require classroom management, though learners may be encouraged to scaffold each other's learning through assessment here.

Portfolio

The gathering together of multiple forms of evidence of competence in given topics or skills. Portfolios are useful in vocational and practical contexts, and can be assembled at the learner's own pace, promoting autonomy. Over-evidencing can be an issue, and there need to be checks that the evidence is authentic and accurately cross-referenced to learning objectives.

Practical activities and products

Learners' skills in action can be assessed live, both in process and by the result or product. This actively involves learners in their own assessment, and can be done in group or solo contexts. Resourcing and equipment issues may be a factor, as may time limitations to realistically complete practical projects.

Presentations

Learners producing and delivering supported talks on a topic. Academic and transferable skills may be assessed, as well as communication and public-speaking competencies. These can be time-consuming to assess, though, and may be awkward to stage in classrooms, as well as dull for non-participants of multiple presentations are being staged to the class.

Puzzles and worksheets

Puzzles may take a range of forms (word searches, crosswords, maths games, gapped handouts) and can be used as short though engaging activities to embed or evidence knowledge. They can be time-consuming to curate, though, and may seem childish to older learners. Puzzles may not address higher-level competencies, though can be useful for assessing recall.

Questioning

Whether written or oral, or closed (Yes/no responses) multiple choice, or open-ended, the use of questioning in its many varieties is a mainstay of assessment. The breadth of questioning possibilities makes this a useful technique, though care must be taken when phrasing questions so there is no ambiguity in the direction required (unless dealing with ambiguity is part of the test).

Role play

Learners exploring hypothetical contexts within role-play can be fun and engaging, though offers both participation and can link theoretical to real-world situations straightforwardly. Classroom management techniques may be required to keep the role plays on course; some learners may be unwilling to participate, citing embarrassment or perceived childishness of the task.

Tests

Often slightly less formal than examination, though assessing similar situational competencies as well as subject-specific skills, teats are a good way of checking learning as well as preparing for examinations ahead. Can be time-consuming to grade, though are often straightforward to administer. Depending on the test design, feedback may be time-consuming.

Tutorials

Discussing with learners, either in groups, i.e. one-to-one, is a good way of being able to explore engagement with a topic, or with learners' perceptions of their education. Tutorials need to be confidential, comfortable for all, and have sufficient time dedicated to them so that they are not rushed (Gravells, 2015).

As you might appreciate from this list and the brief descriptions which accompany the types of assessment, the varieties and uses of assessment can vary depending on the contexts of the session, the types of learners being engaged, the skills being evidenced, the relevance to the qualification, and a host of other potential logistical and other parameters. Whatever methods are being used in each session, though, there needs to be consideration of the learners' needs, the usefulness of the assessment in developing learning, the evidencing of achievement, and the opportunities affording in developing the learner further, both in respect of their subject-relevant competencies, and towards whatever summative assessment methods will be used to gauge their end of course abilities.

Reflection

The list is not exhaustive, as has been mentioned above. So, what could you add to that list? And what would the relative strengths and issues with those new assessment methods be?

How straightforward dis it, do you think, to provide a diet of assessment which is relevant and engaging to your learners, yet diverse and effective in terms of your need as an educator to check that progress is being made?

What support might you expect from colleagues and from outside bodies, such as examination boards, in helping you prepare to assess learners both formatively and summatively?

What kinds of assessment works best for you as a teacher? Why is this?

Conclusion

Assessment is both a goal in education, as a means of determining the success or otherwise, and the level of success, of a learner within a course of instruction. But the final assessment only ever tells part of the story of the educational journey. As educators, there is an obligation to offer education which is challenging yet stimulating, relevant yet testing, realistic where this is appropriate, and levelled appropriately.

While this is being done, there needs to be some consideration of the final element of the course; the summative assessment. It may feel reductive to being assessment back to the end of course examination or performance, but the realities of much certificated or compulsory education are that final grades matter, not only to learners as evidence of their level of achievement, but to subject departments and to whole schools as a kind of scoring mechanism as to their effectiveness. Assessment and their outcomes, therefore, are important at several levels, and it is the work of the capable educator to effectively articulate these at times competing pressures.

Reflection

Now you have finished the chapter, you should:

- Be able to define assessment

- Be able to appreciate the centrality of why assessment is important to learning

- To be able to consider the relevance of an assessment for learning approach

- To be able to consider the usability of multiple assessment methods

- To be able to select appropriate assessment methodologies

Reference list

Bartlett, J. (2015) Outstanding assessment for learning in the classroom. Abingdon: Routledge.

Berry, R. (2008) Assessment for learning. Aberdeen, HK: Hong Kong University Press.

Brown, M., Fautley, M. and Savage, J. (2008) Assessment for learning and teaching in secondary schools. Exeter: Learning Matters.

Clarke, S. (2014) Outstanding formative assessment: culture and practice. London: Hodder Education.

Gravells, A. (2015) Principles and practices of assessment: a guide for assessors in the FE and skills sector. London: SAGE Publications.

HM Government (2014) How many qualifications will count towards the Progress 8 measure? Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/285990/

P8_factsheet.pdf (Accessed: 10 November 2016).

Klenowski, V. and Wyatt-Smith, C. (2013) Assessment for education: standards, judgement and moderation. London: SAGE Publications.

National Foundation for Educational Research (2012) Getting to grips with assessment. Available at: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/pdf/getting-to-grips-with-assessment-1.pdf (Accessed: 9 November 2016).

Wiliam, D. (2009) What is assessment for learning? Available at: http://www.dylanwiliam.org/Dylan_Wiliams_website/Papers_files/Cambridge%20AfL%20keynote.doc (Accessed: 10 November 2016).

Young, E. (2006) Assessment for learning: embedding and extending. Available at: https://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/Images/Assessment%20for%20Learning%20version%202vp_tcm4-385008.pdf (Accessed: 10 November 2016).

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: