Reflective practice: models of reflection lecture

Introduction

This chapter, and 2.2 which follows, will explore reflective practice as a key element of best practice in teaching. From the time of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, to whom Plato attributed the adage that the unexamined life is not worth living, reflection on one's teaching has been thought to be of central importance in developing both as a professional educator and as a person in more holistic terms (Jowett, 1994).

Chapter 2.2 considers in more detail questions related to why reflection is thought to be so central to pedagogic practice. This chapter has as its focus on the 'how' of reflection. Five models of reflection are presented and analysed in respect of their strengths and weaknesses. As you will appreciate as you work through the chapter, there are broad similarities between the models - they are, after all, attempting to frame the same process, though they take different approaches in doing so - though each have their own particular applications.

The selected approaches are well-known in the field of reflective practice, though they represent only a selection; there are many other models available, and it may be that one or more of those models makes better sense to you that any of the five presented here. To some extent, then, this chapter may be considered a jumping-off point for a career-long investigation into reflection. After each model is presented, reflective sections will prompt you to engage with that model so you may assess for yourself how you feel the model might be appropriate in supporting your development as a fully reflective practitioner.

Learning objectives for this chapter

By the end of this chapter, we would like you to:

- Be able to apply the key principles of alternative methods of reflective practice

- Be able to make assessments of the value of competing approaches to reflection

- Appreciate the relevance of developing through reflection in your teaching

- Be able to select from alternative methodologies for reflection, depending on the context to be reflected upon.

Get Help With Your Education Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional education essay writing service is here to help!

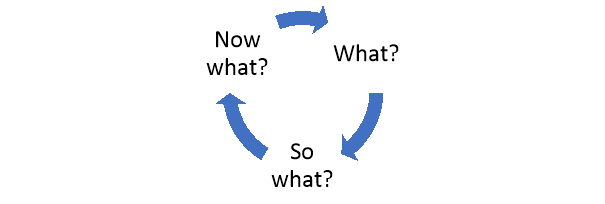

Rolfe et al.'s (2010) reflective model

Rolfe et al.'s model has the virtue of simplicity and straightforwardness. The model is based on three key questions, as the diagram below indicates:

Adapted from Rolfe, Jasper, and Freshwater (2010)

The model was developed initially for nursing and care education, but has become more broad in its subsequent applications, not least because of the clarity of the model and its ease of use.

The three stages of the model ask you to consider, in turn, what happened, the implications of the occurrence, and the consequences for future conduct. The model is cyclic, indicating a continuity. The changes in behaviour or approach which is generated from the reflective thought can then be analysed, and either a further revision made, or else the changes made can be found to have been appropriate.

Rolfe et al. (2010) suggest a series of questions which may spring from the initial three; these may be used to refine reflective thinking and isolate the key elements of the situation or occurrence so that they can be understood in more detail:

What?

This element of the cycle is concerned with describing the event or occurrence being reflected upon, and defining one's self-awareness in relation to it. All questions in this section begin with 'what?':

What:

- Is the issue / problem / reason for being stuck / reason for feeling ill at ease / reason there is a clash of personalities?

- Was my role in the developing situation being reflected upon?

- Was I trying to achieve?

- Actions were being done towards the achievement?

- Were the responses of other people?

- Were the consequences for the learner/s?

- Were the consequences for me?

- Were the consequences for other people?

- Feelings were provoked in the student/s?

- Feelings were provoked in me?

- Feelings were provoked in other people?

- Was positive about the experience?

- Was negative about the experience?

- Could be improved?

So what?

This aspect of the Rolfe cycle analyses the situation being reflected upon and begins to make evaluations of the circumstances being addressed. All questions in this section begin with 'so what?':

So what:

- Does this tell me about myself and my relationships with learner/s?

- Was my thought process as I acted?

- Did I base my course of action on?

- Other approaches might I have brought to the situation?

- Might I have done differently to have produced a more positive outcome?

- Have I learned because of this situation?

- Contextual issues have been brought to light by this situation?

Now what?

This is the element of Rolfe's cycle which is concerned with synthesising information and insight, as we move from the previous elements to think in more detail about what to do differently in the future (or perhaps, if it is more appropriate to maintain the previous course of action) and so be prepared for what might be done if similar situations present themselves again. All questions in this element start with 'now what?':

Now what:

- Do I need to do make things better?

- Should I ask of others to support me?

- Do I need to avoid in future?

- Have I learned?

- Will I recognise in advance?

- Have others learned from this?

- Broader issues need to be considered if the new set of actions are to be enacted?

- Wider considerations need to be addressed?

These questions are only suggestions. Not all may be appropriate for all contexts, and thinking of new ones may be part of the processes of reflection being entered into. One tactic which may be of use if to use the questions above as a cheat sheet; remembering the three core questions might be easy, but the follow-up questions can be stored for use as required. Using them as a template for a form on which to compile written reflection can be a useful strategy, as the writing process helps to formalise ideas, and the outcomes may be stored away for later reference, or else as evidence that reflection has been entered into.

Evaluation of the model

The core advantages of the Rolfe model relate to its simplicity and clarity. Reflective tools need to be accessible and useful to the user, and to produce meaningful results. A simple model such as this can support that. Issues related with the model include the idea that if applied only at the level of the three core questions, then a full inventory of the situation being reflected upon may not take place, and the insight produced as a consequence might tend to the simplistic or descriptive.

Rolfe's own writing indicates that is important not only to consider reflection after the event, but reflection in the moment - as an event is taking place - so that immediate corrective action may be considered. For Rolfe, though, this model does not fully articulate the position due to its simplicity, reflection is not only a summary practice, but to be engaged with proactively (Rolfe, 2002).

Reflection

Does this model make sense to you? What about it is appealing? Are there elements of the model which are less attractive? If so, what are they, and why is that?

How straightforward would it be to use Rolfe's model in reflecting on a lesson? What about in reflecting on an unexpected incident?

How confident would you feel when reflecting in-action (in the moment) as opposed to turning to reflection as a summary activity (reflection on action)?

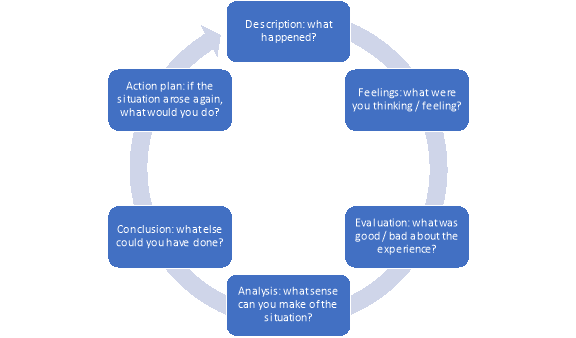

Gibbs' reflective model

Gibbs' (1988) model of reflection, like the Rolfe model described above, was originally devised for nursing, but - like Rolfe's work - has become popular across many disciplines, and is widely applied as a prominent model of reflective practice. This model is cyclic and has six principal elements:

Adapted from Gibbs (1988).

Description

In this element of the cycle, you recount what you are reflecting upon, giving a descriptive account with contextual information as appropriate. If reflecting to others (as a piece of academic or report writing, for example) make sure that they have all the relevant information. If using Gibbs to reflect to oneself, they though you might have all of that knowledge to hand, it can be useful to make notes of such details for clarity and for comprehensiveness of the reflection.

Feelings

In this section, you look back on your emotional state and your rational thoughts about the situation or occurrence being reflected upon. How were you feeling at the time? Was this normal for you? How did your emotions and thoughts alter (if at all) after the situation arose? Be accurate and insightful in your reflection.

Evaluation

In the evaluative element of the cycle, consider how well the situation was handled. Look for positives as well as negatives; be fair to yourself and to the contexts of the event being reflected upon. How did you react? How did others around you respond? Was the event being considered a good or a bad one? Was a resolution arrived at? If not, why not? If a conclusion was made, then how was that done, and was it effective?

Analysis

Here, think about the individual aspects of the event which might have been crucial, and whether they are positive or negative towards the event unfolding. It may be appropriate to integrate pedagogic theory with practice here; were actions informed by a particular paradigm or insight when perhaps there were alternatives which might have been more appropriate, for example?

Conclusion

As you conclude your investigation of what has occurred, it may be relevant for you to consider possible alternatives to the course of action that you took, whether other options could have been applied instead, and what might have happened differently if those alternatives had been executed. If the way you acted ended in a positive outcome, then recognise this, so that you can begin to draw plans to consider taking the same direction if the same situation arises in the future. If the situation was negative in some way, this is the part of the cycle where you consider how to ensure that there is no recurrence.

Action plan

The action plan is your guide for future action. This section is crucial, as it is here that you identify what you will do (and thus, what you will not do) to ensure an improvement in your handling of similar situations in the future. Action plans are useful spurs for discussions with peers and other colleagues; do they agree with your proposals for action, and do they have any insight or experience which might inform your action planning?

Moving through the six stages of the cycle effectively should mean that you will be better equipped for the future is events like the ones being reflected upon here occur again. Your action plan should feed into your approach, and so may form a part of the descriptive element of the next round of reflection.

Evaluation of the model

Advantages of Gibbs' cycle include the focus which is placed on a systematic consideration of separate phases of a learning experience. Though it is more developed than the core three questions of Rolfe's model, Gibbs' headline elements are nevertheless straightforward and accessible, and so they can encourage clear reflection which can be made meaningful to others.

The potential disadvantages of Gibbs' model are that it tends to the descriptive, and may not provide the analytical rigour required to fully appreciate the implications of certain courses of actions of others, or of the thought processes underpinning those actions being taken. The model is one-sided, so it takes into consideration the practitioner's perspective only; there is no room in Gibbs' cycle to take into consideration those on the other side of the event or situation being addressed, and there may be useful insight here to be considered (Jasper, 2013).

Reflection

Do the criticisms of Gibbs' model make sense to you? To what extent might one want to take into consideration others when reflecting on an event? How might the perceptions of other people be incorporated into one's reflection?

Could Gibbs' cyclic model be used effectively in the moment as opposed to after the event? If not, why do you think that this is?

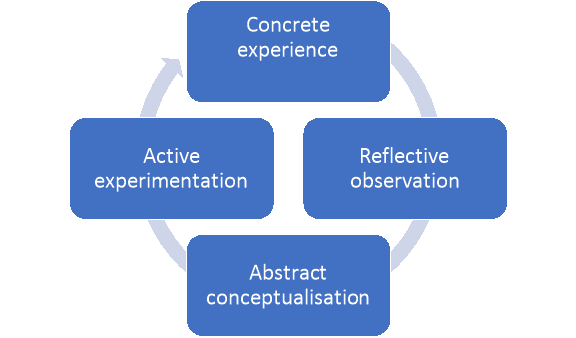

Kolb's Learning Cycle

David Kolb's approach to reflection takes a somewhat different approach in some ways, as it sites reflection as part of a wider set of processes in which the learner (in this case, the educator reflecting on their practice as part of their continuing professional development) seeks to understand their working processes as they move through different stages of engagement with an event, occurrence, or training session and take on relevant aspects of the new material (Kolb, 2014).

Kolb's cycle derives its insight from experiential thought as regards learning processes, and to some extent it is an offspring of work done by theorists such as Lewin, Piaget, and Freire. The learning cycle proposed by Kolb is experiential in that the focus is upon the value of experience to learning. What is also distinctive about this model is that reflection forms part of a wider set of processes, rather than the model being purely concerned with reflection. To this extent, then, the experiential learning cycle as outlined by Kolb could be used in association with another, and reflection-specific, model of reflection.

This diagram (adapted from Kolb, 2014) indicates the main elements of Kolb's experiential learning cycle:

Concrete experience

For Kolb, any process of learning, including learning as a consequence of embarking on an instance of reflection, begins with a concrete - real - experience. Our stimulus to learn in this model derives from having experienced something, and then on the taking into consideration of the meaning and impact of that experience.

Vicarious or second-hand experience (such as reading about how to become a teacher, for example, or watching a demonstration video) is not enough to fully appreciate the situation, event, or skill being studied. Only actual live experience gives the learner the complete picture.

Reflective observation

The second stage, reflective observation, involves taking a step back from the experience so that it can be properly considered. Processes related to reviewing what has been done, the effectiveness of the approaches being taken, and the possibility of alterations or variations to the concrete experience already undertaken can be considered.

Kolb appreciates that for some, this is a more natural process than it might be for others. Some people are organic in their reflective abilities, whereas others have to be more formal and structured in their approach to looking back on their experiences and drawing insight for the future from them.

Abstract conceptualisation

For Kolb, conceptualisation means to draw inferences from our experiences and what they mean to us. We can take ideas generated as a consequence of reflecting on our experiences, and then draw conclusions from them. In the abstract conceptualisation phase of the cycle, we are prompted to make sense of our experiences, and better appreciate the relationships between them and our wider world.

This can mean further reflective thinking guided towards linking our practice with wider theoretical concepts (such as connecting live teaching events to a range of learning theories which may explain them in various ways). Insight may also be taken from colleagues, peers, from one's own previous history, and from parallel experiences. All of this can support the making of fresh meaning from the concrete experience which we have engaged with through the cycle.

Active experimentation

The active experimentation phase of Kolb's cycle is where the hypotheses generated in the previous element are put to the test. It may be that multiple possible alternative approaches have been provoked by the process of working through the cycle, in which case it may be appropriate to test them all in live situations. From such experimentation, fresh concrete experiences will be encountered. Learning must be enacted, not just considered in the abstract; this fresh concrete experience is vital for learning to become embedded.

It is not enough, however, merely to test alternatives or to be assured that one's previous way of working was the most appropriate to the circumstances. For a full appreciation, the cycle must be continued, as we continually re-assess the usefulness and the meaning of our experiences, and as we seek make further improvements.

Evaluation

Kolb's ideas have been influential, not least in the development of other approaches which have taken inspiration from Kolb. The learning cycle may be used also in partnership with other schemas of Kolb's, most notably the definitions of four styles of learning which he developed alongside the cycle. For Kolb, there are four kinds of learners (Chapman, 2016):

- Divergent thinkers: Divergent thinkers are able to assimilate ideas from a spectrum of sources and theoretical approaches. Divergent thinkers are sensitive, imaginative, good at brainstorming and coming up with multiple alternatives to addressing a problem or situation, as well as being good in group-working situations, and in tackling research exercises

- Assimilators: Assimilators prefer logical, short, factual approaches, and work well with clarity and with making sense of theory and abstract concepts. Learners and reflectors who tend to being assimilators like to take time to think through the relative merits of different positions, and can synthesise material efficiently.

- Convergent thinkers: Convergers are adept at problem-solving, and in technical operations, particularly those with real-world applications. There can be a focus on technical or technological subjects, and on experimentation as a way of exploring the world.

- Accommodating thinkers: Accommodators respond well to active experimentation, to inspiration and to intuition rather than a logical and ordered approach. This kind of learner likes working in group environments and using the knowledge of others to support their own decision-making.

Disadvantages of Kolb's ideas include the observation that his categories and processes are a personal design and as such are asserted rather than 'proved' in any meaningful way. The experiential cycle proposed may not be a good fit for all reflective situations, and may also require articulation with another reflection-centric approach for it to be meaningful. In addition, the separation between stages in the cycle as outlined by Kolb may be artificial, and not mirror actual experiences where multiple aspects of the learning cycle may be encountered simultaneously (Pickles and Greenaway, 2016).

Reflection

Kolb's ideas have been used to inform a variety of processes, not least as a guide to lesson planning, with each lesson following the four-step cycle and leading to the next lesson in turn. Can you see the usefulness of such an approach? What about its limitations?

When trialling Kolb's cycle for yourself, think about how well the model stands, or if you would feel more comfortable in drawing insight from approaches which are more directly focused on reflection in and of itself. If so, which other models might you consider?

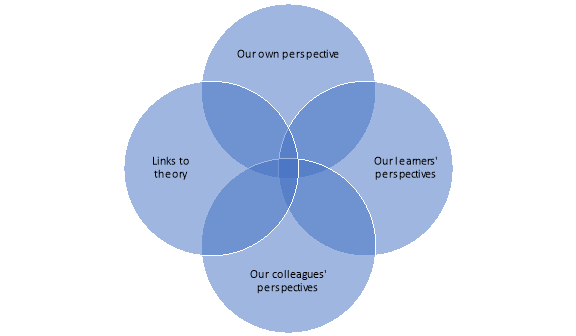

Brookfield's four lenses model

The models we have discussed thus far in this chapter have each taken process or cyclic ideas as their inspiration, suggesting a series of steps to be undertaken in sequence, and then feeding back into the start point of that sequence to begin a further cycle of reflection. Brookfield's model takes a different stance, and asks us to consider teaching practice not in cyclical terms, but from multiple perspectives.

In Brookfield's schema, we should consider reflection from four perspectives: from our own standpoint, from that of our learners, from that of our colleagues, and from its relationship to wider theory. Only from the consideration of multiple points of view can we deepen our reflection. The four lenses Brookfield suggests may be presented in diagrammatic form:

Adapted from Brookfield (1995)

Ourselves

For Brookfield (1995), the autobiographical aspect of reflection, when we look back at our own experiences and feelings, is central to any valid process of critical reflection. We may draw from our own past as well as from the immediate contexts which may have provoked the reflective journey. Brookfield suggests that a thorough inventory is taken, so that we do not merely re-assess the moment, but that we look back at our pasts as teachers, as trainees, and as learners ourselves, in order to be able to work towards revealing the full nature and extent of elements of our teaching practice which may require reappraisal.

This can involve reassessment of emotions as well as factual elements; self-review may be difficult and uncomfortable, particularly at first, but it is a necessary step towards testing those aspects of ourselves as teaching professional s which may have relied too much on assumption.

Our learners

The consideration of the students' perspective/s may yield insight which might otherwise have been missed if the focus of the self-reflection had been purely upon the individual themselves. Student-oriented reflection might encompass looking back at work produced by learners, at their feedback and grades, at tutorial records and at learner-generated journals. Survey and questionnaire data on quality of teaching and of classroom experience might be valuable also.

One object of this focus is to work to perceive hidden assumptions, biases, and unequal articulations of power which may have provoked teaching which might have been better and more even-handed. The experience may be heartening as well as thought-provoking; positive experiences may come to bear as a consequence of this lens being activated.

Our colleagues

A further mode of investigation into the self involves going beyond learners and involves taking peers and other colleagues' perceptions and observations into consideration. Peer observation and other review processes can reveal biases and assumptions in one's teaching, and can bring to light aspects which one might not consider otherwise. Paired or mutual investigation with colleagues can be beneficial for all, as there will invariably be points of commonality and aspects where improvement or where less awkward alternatives to teaching strategies being currently used might be shared.

Benefits can include the fostering of team working, or further engendering collegiality among teaching peers, and provoking ideas for collaboration and for practice-driven research. Sharing of experience can break down barriers, can foster diversity in teaching through that sharing, and can also make fresh connections across subjects and levels.

Theoretical contexts

For Brookfield (1995), teachers need to be engaged in the investigation of their teaching practice; the training of teachers does not end with the final assessment of the teacher training course, but is instead a life-long journey. Engagement with critical reading, with subject scholarship, with the political and other contexts of contemporary teaching, and with higher qualifications all serve to deepen and refresh the connections between pedagogy in practice, and with critical engagement with that practice.

Teachers may also realign themselves with theory through a re-engagement with critical reading, and may derive fresh insights from their experience of reviewing their practice from an array of theoretical standpoints. This kind of engagement fosters links beyond the immediate setting, and the knowledge and experience of one's peers and out towards broader communities of knowledge. A full investigation of oneself and one's practice, then, takes in multiple considerations, and applies them back to one's teaching, which can then be informed not only by a subjective response to reflection, but may be filtered through peer, theoretical, and through learner engagements also (Trevitt, 2007).

Evaluation

One advantage of Brookfield's model as outlined here is that it takes a holistic perspective, and addresses teaching from a selection of standpoints. It may be thought particularly useful for making summary observations, for example as part of end of year reviews, or in reflecting on engagements with a training course. The breadth of observations may ne insightful also.

Issues with the model as described may include the point that the model is less useful for making assessments of teaching in action; it is more suited to summative, rather than live, reflection, and perhaps is less useful for immediate use as a consequence. In addition, the lenses may be difficult to articulate, and require not only time-consuming and detailed working, but result in a variable and skewed picture.

Reflection

Brookfield asks us to consider ourselves as teachers from multiple standpoints. What would your learners say about you? What about your peers? How might your perception of what they might say differ from what they would indeed say if asked?

How would you align yourself against the political, economic, cultural, and social contexts in which your teaching takes place?

Could you use Brookfield's lenses to fix a specific problem, or an issue that occurred in a single teaching session? If so, how might you go about this?

Johns' model of structured reflection

Like the Gibbs and Rolfe models outlined in previous sections, Christopher Johns' work on reflective practice was originally developed in a nursing context, but has since become widely applied across a variety of disciplines, including education. Johns' approach to reflective practice has become influential, not least because it provokes a consideration in the individual of matters which are external to them as well as elements which are internal to the practitioner. There are two sets of related processes in this model; looking in, then looking outwards.

Looking in

First, the practitioner is asked to look inwards upon themselves and recall the experience being analysed. It may be useful to write notes to clarify one's memories. Write a descriptive account of the situation, paying attention to the emotions conjured up in the moment of the event being reflected upon, and those emotions and other thoughts which have been provoked since. Take note of issues arising from the event and its consequences.

Looking out

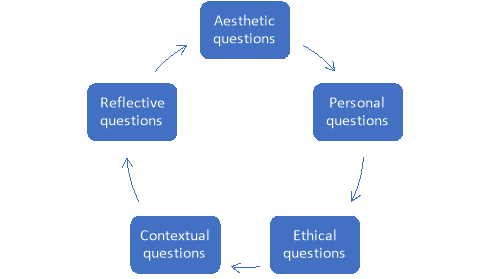

The looking out element of the model is structured around five key sets of questions. The diagram below indicates the working of Johns' (2013) model:

Model of structured reflection, adapted from Johns (2013)

Aesthetic questions

Aesthetics in the sense in which Johns is using it means questions raised in relation to one's sensory perceptions, rather than in the more common usage of referring to an appreciation of art and beauty (Oxford Dictionaries, 2016a).

For Johns, aesthetic questions include:

- What was I trying to do?

- What did I react in the ways that I did?

- What were the repercussions for myself / for others?

- How did others feel?

- How did I know what others felt?

Get Help With Your Education Essay

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional education essay writing service is here to help!

Personal questions

Personal questions relate to self-examination, and ask if you can identify the nature of your actions and reactions, and the elements which influenced or provoked those. Relevant questions to ask here include:

- What internal factors influenced my actions?

- How was I feeling at the time of the event?

- Why was I feeling this way?

Ethical questions

Ethical questions in this model relate to the coherence of your actions when compared to your moral and professional codes. Was how you acted consistent with your sense of self, and the values which you usually embody? Relevant questions to ask may include:

- To what extent did my actions in this instance match my wider beliefs?

- Was I acting in an uncharacteristic way?

- If so, what elements came together to influence me to act in a way contrary to my usual behaviours, or at odds with my sense of ethics?

- Did I act with best intentions?

Contextual questions

The contextual element of the model asks you to consider if there were environmental or other factors acting on you from outside. Relevant questions to ask here include:

- What outside influences were a work?

- Were those influences reasonable?

- Who or what informed my actions?

- Would I have acted differently with alternative outside information?

Reflective questions

Some versions of Johns' model refer to this section as asking empirical questions; the word 'empirical' in this usage meaning being based on evidence, observation, and experimentation (Oxford Dictionaries, 2016b). The process of working through the reflective cycle has generated evidence based upon your observations, and that leads you to be able to make assessments. Relevant questions to ask here can include:

- How does this event compare with other similar ones?

- What could I have done differently?

- What might have been the outcomes of such alternative approaches? Consider this regarding yourself, other colleagues, and the learner/s.

- What are my feelings about the event now?

- How might I work to act more positively in the future for the benefit of all?

- How have I changed because of this event?

Evaluation

Johns' model is useful in that it encourages reflection taking into consideration a range of standpoints, and that the reflector is provoked to consider the impacts of their actions not only on other people, but on themselves in respect of its congruence with their own values. However, the model may be of limited use in some contexts as it is focused on the analysis of specific individual events rather than on wider questions.

The approach may be of relevance to troubleshooting problematic sessions or encounters with learners that went wrong in some way, but the model assumes a context of good practice to contrast the behaviour being reflected upon. The model has a narrative aspect to it, timelining events and feelings towards those events, but there is the danger that if applied superficially, the model may only lead to obvious and descriptive findings.

Reflection

To what extent does Johns' model feed back into new teaching? Or is it perhaps best seen as a troubleshooting tool?

How much information might you need to analyse an event using this approach? How long would the process take?

Can you see the appeal of Johns' model over other approaches to critical reflection? If so, what is attractive about his approach to being reflective? Are there any elements which you do not respond to? If so, what are they? And why?

Conclusion

Reflective practice is a cornerstone of development as a professional, no matter what the field one is engaged in. The five models presented in this chapter evidence that importance, as all are invested in ways to have practitioners think on themselves and their actions, and to have those experiences being reflected upon become meaningful through scrutiny, so that performance might be improved, so lessons might be learned, and so that mistakes might not be repeated.

That is not to say that reflection is a negative activity; even though the trigger for reflection might be a situation that might have been handled better, the outcome of engagement with a rigorous and honest process of reflection will be development and self-knowledge. This will feed, as many of the paradigms shown here have indicated, directly back into teaching practice which has been enhanced by the reflective activity.

The chapter which follows - 2.2 - develops the examination of reflective practice started here. The focus there is on the importance of reflection, on its positives in respect of your growth as an educator, while also exploring limitations. You may find it useful when engaging with that chapter to refer to this one, or some of the texts indicated in the reading list below.

Reflection

Now we have completed this chapter, you should be able to:

- apply the key principles of alternative methods of reflective practice

- make assessments of the value of competing approaches to reflection

- Appreciate the relevance of developing through reflection in your teaching

- select from alternative methodologies for reflection, depending on the context to be reflected upon.

References list

Brookfield, S.D. (1995) Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Chapman, A. (2016) Kolb's learning styles, experiential learning theory. Available at: http://www.businessballs.com/kolblearningstyles.htm (Accessed: 24 November 2016).

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. London: FEU.

Jasper, M. (2013) Beginning reflective practice. 2nd edn. London: Cengage Learning.

Johns, C. (2013) Becoming a reflective practitioner. 4th edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jowett, B. (1994) Plato's 'Apology'. Available at: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html (Accessed: 24 November 2016).

Kolb, D.A. (2014) Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Pearson FT Press.

Oxford Dictionaries (2016a) Definition: Aesthetics. Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/aesthetic (Accessed: 25 November 2016).

Oxford Dictionaries (2016b) Definition: Empirical. Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/empirical (Accessed: 25 November 2016).

Pickles, T. and Greenaway, R. (2016) Experiential learning articles + critiques of David Kolb's theory. Available at: http://reviewing.co.uk/research/experiential.learning.htm#axzz4QwTbJCEX (Accessed: 24 November 2016).

Rolfe, G. (2002) 'Reflective practice: Where now?', Nurse Education in Practice, 2(1), pp. 21-29. doi: 10.1054/nepr.2002.0047.

Rolfe, G., Jasper, M. and Freshwater, D. (2010) Critical reflection in practice: generating knowledge for care. 2nd edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Trevitt, C. (2007) What is critically reflective thinking? Available at: https://www.learning.ox.ac.uk/media/global/wwwadminoxacuk/localsites/oxfordlearninginstitute/documents/supportresources/lecturersteachingstaff/resources/resources/CriticallyReflectiveTeaching.pdf (Accessed: 24 November 2016).

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: