Organisational Culture Lecture

1.0 Introduction

Organisational culture is a fundamental factor which influences the behaviour of organisations. However, culture is also intangible and can be difficult to define and truly understand. For example, whilst it is possible to understand surface elements of culture, such as branding and organisational reputation, it can be difficult to identify and understand the more subtle nuances of organisational culture such as unspoken rituals and tacit rules. Academics recognise these difficulties, and have spent considerable time researching and comparing aspects of organisational culture, and also aspects of national culture in order to understand whether or not there are any consistent factors which can help us to identify culture and also understand its implications. This chapter therefore begins by examining exactly what culture is and what it means, before looking at different types of culture and some of the most popular theories which can be used to understand it.

The chapter also includes a discussion on the importance of culture, and why it matters for us to understand something which cannot necessarily be easily identified or measured, particularly in a world of increasing globalisation where it is more likely than ever before that you will find yourself working in a multicultural environment. The chapter also includes practical examples on issues such as how to handle international work placements and the advantages and disadvantages of managing organisational culture and potentially also attempting to change culture, something which is recognised as being one of the most difficult jobs a manager or leader may face. The chapter includes examples and questions to help you think about these issues, and consider what you would do if these types of situations arise in your workplace.

2.0 What is culture?

Organisational culture has a number of different definitions, but it is broadly understood to mean the actions, values, and behaviours, which, in combination, contribute to the overall philosophy and environment of the organisation. Culture ultimately shapes the way in which employees behave and make decisions, which can be both positive and negative. Culture is formed over time as a result of the experiences and values of the organisation and the way in which it reacts to internal and external circumstances. Culture has been described by some as the “glue which holds organisations together” (Reiss, 2012, p.1), and whilst certain aspects of culture are obvious and explicit, other aspects of culture are tacit and difficult even employees themselves to identify. In the words of Bower, (2003, p.ii) who was paraphrasing Charles Handy “culture is the way that things are done around here”.

Landy and Conte (2016, p.8) describe culture as being a combination of “shared attitudes, beliefs, customs and written and unwritten rules that are considered valid”. They go on to explain that there are a number of indicators of organisational culture, such as:

- The way in which an organisation treats its employees, customers, and wider stakeholders. In short, the way it conducts itself in business;

- Organisational attitudes towards decision-making, for example whether there is freedom in decision-making or whether there is a rigid organisational hierarchy;

- The treatment of power, knowledge, and information within the organisation, for example is knowledge shared freely or hardly distributed at all;

- How employees react to their organisation, and whether they are committed and engaged and care about the values of the organisation or whether it is nothing more than a job.

Culture is important because all of these factors in combination directly impact organisational performance and profitability, as well as setting out unwritten guidelines on aspects such as concern for the customer, quality, innovation, and corporate social responsibility.

Interestingly, whilst organisations may set out an explicit written statement of what they believe their culture is, the way in which employees behave is far more likely to reveal the true culture of the organisation. Customers are also sensitive to the way in which organisational culture influences activity, particularly if there is friction between a written organisational statement of beliefs and values, and the actuality of what the organisation does. An example might include fashion brands stating that they have a concern for the environment, but using child labour. Misalignment between what an organisation says and what an organisation does in terms of its culture is highly revealing and can be used to help us understand whether there is a synchronicity in organisational culture or whether there are likely to be deeper problems.

In order to understand how and why an organisation may either have a positive or negative culture, it is helpful to examine different theories of organisational culture, and also national culture, as wider external factors also influence the way in which organisations behave. It is important to remember that organisational culture is unique, and while it may be possible to loosely categorise an organisation on the basis of its actions and behaviours, it is also important to remember that culture, whilst deeply embedded, is not static and may potentially have different aspects which should be considered.

Q - What examples can you think of for organisations which appear to genuinely represent their culture and those which appear to have differences between what they say and what they do? How does this make you feel about these organisations?

Need Help With Your Business Assignment?

If you need assistance with writing a business assignment, our professional assignment writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Assignment Writing Service can help today!

3.0 Types of Culture

Earlier in this chapter we mentioned that there are different ways of trying to understand culture. This is easier to understand if we first look at the different types of organisational culture, and then the different types of national culture. These represent different areas of academic research, but they are interrelated because the geographic (National) location of an organisation is known to influence aspects of organisational culture. This has implications for international business and globalisation, and also for any employees who work on international basis.

3.1 Organisational

There are many theorists who have attempted to describe or measure organisational culture. There are differences of opinion between academics as to the best way to define and identify culture, and also how to understand the implications of different types of organisational culture. There is broad agreement amongst academics that there are loose classifications of organisational culture, and that some types of organisational culture are preferable to others, although one important caveat to this is that the national culture of the country in which the organisation is based is likely to exert an impact. For example, there is increasing recognition of the fact that ‘Western’ beliefs about organisational culture do not necessarily directly apply in other cultural settings and vice versa. This is why it is always important to consider different opinions about organisational culture before reaching a firm conclusion. This section briefly describes and also critiques four of the most popular theorists who have examined organisational culture, with examples of their models in practice.

3.1.1 Schein

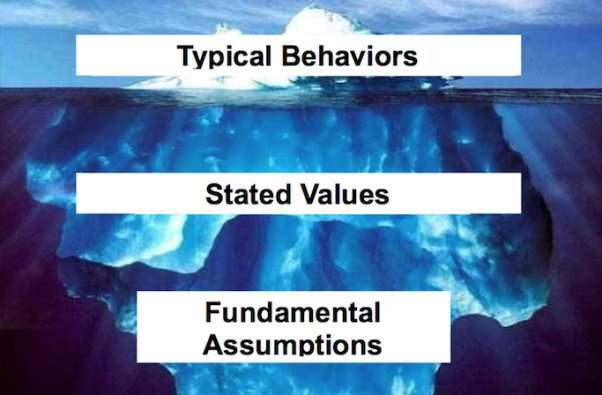

Edgar Schein (2010) is credited with the now famous pyramid or iceberg explanation of organisational culture when he argued that there are three layers of culture in organisations. These are artifacts and behaviours, espoused values and basic underlying assumptions. Reflected in Figure 1 below is an image of this model, shown as an iceberg as this represents the seen and unseen aspects of culture.

Figure 1: Schein’s layers of organisational culture (Adapted from Schein, 2010, p.19)

Schein believed that artefacts and behaviours represent physical manifestations of organisational culture, for example employee uniforms, decor within organisational buildings, branding of organisational products, or equipment and any other physical aspects, such as whether an organisation is proud to display its association with a particular cause. Such artefacts can be readily identified by those external to the organisation and at least partially understood. The next layer includes espoused values which are overt statements of organisational intent and planned behaviour. These might include any mission statements or published objectives, and also any organisational mantras for example a belief in a family firm, or a belief in creativity. Finally, there are basic underlying assumptions about organisational behaviour, and these are likely to include collective belief patterns such as an inherent or subconscious knowledge of decision-making processes such that when faced with a choice, employees would instinctively ‘know’ what would be preferred by the organisation. Such assumptions are often so deeply embedded that it can be difficult for the employees themselves to articulate what they are, or even have an awareness of them, especially if they have worked for an organisation for many years.

Schein’s model continues to be a popular starting point for understanding the basic premise of organisational culture. Schein believes not only that culture within organisations is a response to both external and internal conditions, he also believes that employees anchor themselves to organisational culture and recognise whether or not they will be a good fit, and therefore if they will be happy or at least comfortable in the workplace. Critics of Schein’s theory suggest that it is somewhat superficial in failing to identify types of culture but only constructs. There is also some recent criticism on the basis that in more flexible organisational environments it can be difficult for employees to identify where they fit within overall organisational culture. However, there is a far greater level of support for Schein as an initial diagnostic tool.

3.1.2 Handy

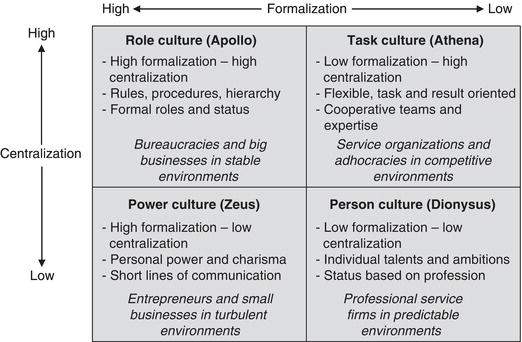

Charles Handy (1996) popularised a framework which links categorisations of organisational culture to evidence in the form of organisational structure. This is reflected in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Handy Organisational Culture (Adapted from Handy, 1996, p.37)

Handy believed that there are four main types of organisational culture which can be identified by the extent to which an organisation is both formalised and centralised. The four types of culture he identified were:

- Role culture

- Task culture

- Power culture

- Personal culture

Role Culture

This is typically characterised by organisations which have a high degree of formalisation and a high degree of centralisation, such as bureaucracies or large stable businesses. There are well established formal rules and procedures, and a well-defined organisational hierarchy which is clearly understood and tightly enforced. The advantage of such a culture is that employees understand exactly what is expected of them, and there are well-defined processes and procedures to follow. The disadvantage of such organisations is that they can be much less adaptive and agile in a changing environment. For especially large organisations, this may not necessarily be a very significant issue, but in some circumstances very large organisations have failed because of their inability to adapt.

Task Culture

These organisations are characterised by a high degree of centralisation but a low degree of formalisation. They are typically quite flexible and results orientated, and often work on a project basis. Examples are likely to include specialist construction firms, or service firms such as architects. They respond well to a competitive environment, but do require individuals to be highly collaborative and communicative, and also be able to work well on their own initiative. Team dynamics are likely to be very important to the overall success of such a culture, which is also why it is important to understand how multicultural teams can influence organisational outcomes. It is not necessarily an ideal environment for those who like structure and regularity in their working day.

Power culture

A highly formalised organisation but often lacking centralisation, such a firm is likely to have a highly charismatic leader who communicates directly with people and expects quick and agile responses. Entrepreneurs are typically associated with this culture, as are small agile businesses capable of operating in a turbulent environment. It is important to distinguish between entrepreneurial businesses and small family businesses, as they are not necessarily one and the same, and some family businesses can often become quite introspective finding it difficult to change their working ways. The benefits of a power culture are that an organisation is quick and responsive, but the disadvantages are that it can be difficult to work for someone who is likely to have strong opinions and may well change their mind quickly, expecting others to keep pace.

Personal Culture

This is a culture lacking in formalisation of centralisation, and is likely to centre on a work environment which is self-directed and status driven. Professional services firms in stable and predictive environments such as accountancy or insurance benefit from this type of overall culture. Its advantages are that individuals operate on a self-motivated basis so need limited formal guidance or structure, but conversely it can be very difficult to marshal people in such culture as they are used to being self-directed, and can react badly to even small changes in rules and procedures.

Handy’s framework is also linked to the idea of visual representations of these cultures (and also as can be seen from Figure 2 loose allocation to Greek mythology), and helps to provide an understanding of how different types of organisational culture physically manifested themselves in overall organisational structure and hierarchy. Handy recognises that in small organisations it is quite likely that culture will continue to be driven by the personality and/or preferences of particular individual managers or leaders, but in larger organisations culture will become self-replicating and self-reinforcing. Critics of the framework suggest that it would benefit from being updated in modern more flexible working environments where established career patterns and organisational structures have less relevance.

Q - What organisations do you know or have worked for which might be classed under any of these descriptions? What aspects of the organisation made you classify them under each type of culture?

3.1.3 Deal and Kennedy

Deal and Kennedy (2000) examined organisational culture from a different perspective, concluding that there are six interrelated elements which define organisational culture. These are:

The history of the organisation, because shared past experiences shape current beliefs and values and the traditions which organisation is built on. For example, firms often draw on their heritage and use this as part of their branding strategy, as well as asserting a belief in traditional values.

The values and beliefs of the organisation are critical as these focus on the shared beliefs of employees and the organisation as a whole, including the written and underwritten activities and behaviours which are accepted as valid.

Rituals and ceremonies, which may be formalised or informal. For example, recognised regular company events such as Christmas or summer parties or award ceremonies. Informal examples might include dress down Friday or bringing in cakes and sweets for people’s birthdays. Over time, these become reinforcing and form part of the culture of an organisation.

Storytelling, which helps new employees understand their position and role in the organisation. Storytelling has long been used as a means of sharing information within cultures and is now increasingly recognised in Human Resources Management (HRM) literature as a way of helping to introduce new employees the organisation, or gradually help to change organisational culture. Stories are often relatable for people, which is why they can quickly become embedded in organisational culture.

Heroic figures are usually former employees of the organisation and are often embedded or immortalised in storytelling. They are a manifestation of organisational values and culture, and may well include the founder of the organisation, or an individual who invented or created something new which transformed the fortunes of the organisation. An example might include Steve Jobs of Apple who acquired near mythical status amongst devotees of Apple products.

Cultural network is the informal but critical social network within an organisation whereby employees share knowledge and acquire social capital. Deal and Kennedy believed that there are specific personalities within a cultural network who help spread information and share stories, and might include the office gossip, the office spy, and the office whisperer, all of whom are key players in the collection and dissemination of organisational information.

Deal and Kennedy conceptualised foundation of organisational culture in their framework reflected in Figure 3, which categorises company culture according to degrees of risk-taking and speed of feedback. In in short, how quickly do organisation's make and implement decisions, and how quickly they are able to determine whether these decisions and strategies were the right ones for their business.

Figure 3: Deal and Kennedy’s Taxonomies of Organisational Culture (Adapted from Deal and Kennedy, 2000, p.58)

Their four categorisations of culture are:

- Work Hard/Play Hard Culture

- Tough Guy/Macho Culture

- Process Culture

- Bet-Your-Company Culture

Each type of culture is identified with the following characteristics:

Work Hard/Play Hard

This is likely to be a sales-driven culture where individual employees take very few risks, but they receive quick feedback on their decisions and actions. Heroes in such a culture are likely to be highly successful salesman, and employees are likely to respond well to internal competitions as well as being motivated by extrinsic rewards, something which runs counter to certain elements of motivation theory. Individuals are typically positive and upbeat and like to chase targets. If managed well, this can be a successful culture where employees work collaboratively to achieve sales targets. If managed badly, it can result in an unfortunate culture where underperforming salespeople are demoralised and operate in a culture of fear.

Tough Guy/Macho

This type of environment is often associated with individuals who are not afraid to take risks but expect quick feedback. Financial traders would be an example, also high performing athletes or music artists. They expect to be recognised for what they achieve, but are less likely to work as part of the team as they are fiercely competitive and can be difficult to manage. It is often associated with a ruthless organisational environment which can be unpleasant and uncomfortable to work in unless an individual has a very high degree of self-confidence.

Process

In a process driven culture, risks are low feedback is slow, and it is unlikely that any single individual will be able to have a great deal of impact on organisational activity. Examples might include large retailers or other transactionally driven organisations which have well established procedures. Individual employees know that they have little impact on organisational outcomes and there is little to link individual organisational decisions to overall goals and objectives. Therefore, employees tend to focus on accuracy in process and procedure believing that ultimately it will deliver organisational goals. Technical expertise and accuracy is valued in such a culture but it can be difficult to accelerate process or change organisational direction. It is likely to be a difficult culture for innovators or entrepreneurial individuals to work in as they will find procedural constraints challenging.

Bet-Your-Company

This is likely to be a high risk environment but one with feedback can be slow often associated with innovation and development such as engineering or pharmaceuticals. Typically such environments involve a high degree of capital investment and expenditure, and also have a long payback period, but one which can be extremely lucrative. However, as it takes a long time to determine whether decisions were right, a great deal of effort and energy is expended in planning and preparation. There is also a high degree of teamwork, as employees recognise that they are mutually dependent upon one another to succeed and believe in long-term planning and forward preparation. The risks associated with this type of culture are found in issues such as groupthink whereby employees mutually reinforce an idea because they are so keen to see it succeed, failing to consider the possible problems.

Although there are many examples of organisations fitting neatly into one of these categories, there is also a recognition of the fact that some parts of the model are more accurate in different situations. In dynamic business environments it is therefore better to identify which aspects of the model have greater relevance and consider the implications of this for long-term management and culture.

Q - What examples can you think of firms which fit into these different categories? Do they always fit perfectly or are there elements which do not fit? What are the implications of this?

Need Help With Your Business Assignment?

If you need assistance with writing a business assignment, our professional assignment writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Assignment Writing Service can help today!

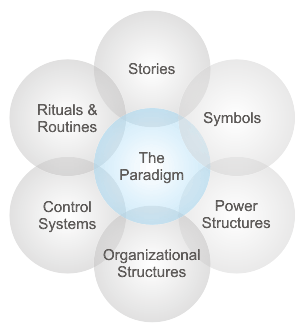

3.1.4 Johnson and Scholes

The cultural web model was developed by Johnson and Scholes (cited in Scholes and Johnson, 2002), (Figure 4), and as can be seen as an extension of the Deal and Kennedy model. It is a practical approach to understanding the culture of the organisation as it is now, and then using this to compare it to the state that the organisation would like to reach at some point in the future. The gap analysis between the current and future state then forms the foundation of a plan to change organisational culture, something which is discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 4: Cultural Web (Johnson and Scholes, 2002, p.119)

The model encourages those within the organisation, (or potentially externally if they have hired consultants to offer a fresh view), a number of questions about the types of stories told in the organisation, what symbols mean and how employees interpret them, and also aspects surrounding structure, power, control, and rituals and routines. As discussed above, culture is self-reinforcing, and if employees continue to tell stories or reinforce structures which have a damaging effect on organisational culture, it will require a change in approach. However, it is possible to make a number of small incremental changes which can lay the foundation for change, such as telling more positive stories rather than negative ones, or setting a professional or creative image by encouraging employees to wear uniforms or adhere to a dress code. In combination, these factors can be used to both identify and then change or adapt organisational culture.

To achieve this change, it is important to map the state of the organisation as it is now and then ask questions about how the organisation would like to be in the future. For example, what aspects of organisational behaviour not positively contributing to the achievement of organisational strategy? Do certain organisational activities need to be reinforced or do they need to be removed? Addressing one aspect of the time and make change less uncomfortable and help to promote the feeling of employees being involved in the change process thereby reinforcing it and embedding it, helping to change culture permanently.

Q - Applying the cultural web to an organisation you are familiar with, what examples can you think of for each element? When considered together, what does this tell you about the organisation?

3.2 National

As mentioned at the outset of this chapter, national culture also plays a role in organisational culture. There are a number of ways of understanding national culture, one of the most popular is that of Hofstede (2017), and another useful framework is that of Lewis (1999) who proposed a visual approach. These models are briefly discussed here.

3.2.1 Hofstede

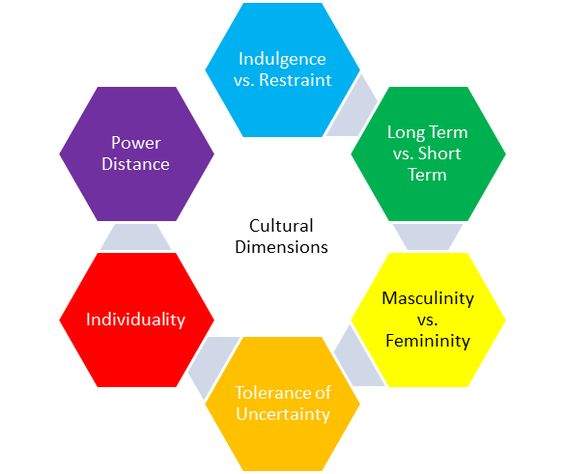

Geert Hofstede (2017) is famous for his cultural dimensions model first presented in the 1980s which originally identified five (now updated to six, the latest being indulgence vs. restraint) dimensions of national culture. This reflected in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture

Hofstede determined, after gathering an enormous amount of data from many different countries, that there are embedded cultural norms and behaviours which influence individual activity. For example, respect for authority, willingness to take risks, and belief in individualism or collectivism. The Hofstede Institute has continued to gather data about national culture and the activities of individuals and organisations, and this seems to reinforce these general categorisations. These are important for understanding the way in which people from different cultures are likely to react to different situations. As with organisational culture it is not an absolute science, and the categorisations are generalisations, but have been repeatedly proven to be reasonably accurate as a starting point. Critics of Hofstede point out that he began gathering his data from a relatively small number of secondary sources, and that the data wasold. However, the fact that they continue to be gathered and tested against multiple different cultural settings, as well as being updated to reflect contemporary trends, means that it continues to be widely used as a measure of national culture and likely organisational and individual reaction.

3.2.2 Lewis

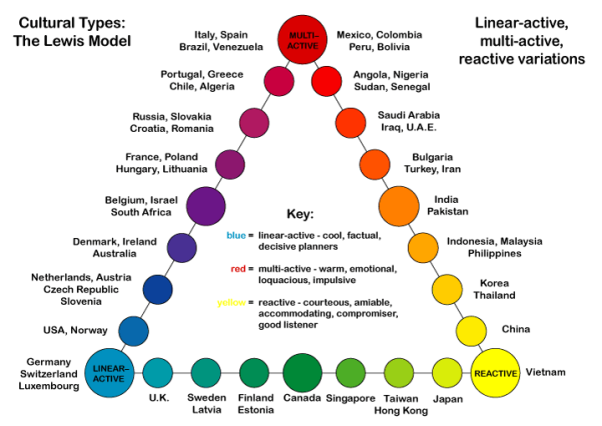

Lewis (1999; 2006) used the founding work of Hofstede to conduct his own research into the way in which people from different cultures communicate with one another. This is reflected in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Lewis Cultural Communications Model

Lewis determined that the cultural background of a person is likely to influence the way in which they communicate, which is important in international business when working in multicultural teams or seeking to undertake international business negotiations. The significance of the model is that it recognises that a failure to appreciate the preferred communication style of another individual may well adversely impact successful communications because assumptions are made about individual communication style. For example, Northern Europeans typically have a detached, linear communication style, and can find it difficult to engage in productive negotiations with more emotive cultures such as Central or South America. Conversely, people from these cultures can perceive Northern Europeans as cold and uninterested in negotiations. Therefore, understanding the perspective of another culture in terms of communication style in a business environment is likely to be critically important to the success of teamwork and ongoing contribution to organisational culture.

4.0 Why Does Culture Matter?

4.1 Multiculturalism

As mentioned in several places in this chapter, culture matters because it informs the way organisations behave, and also the way that individuals within organisations behave and respond. Increasing globalisation and mobilisation of employees has led to a much higher level of multiculturalism in the workplace. This is generally considered to be very positive, because bringing together different perspectives helps to create innovative solutions and also allows organisations to understand the needs of their marketplace. However, it is simplistic to believe that employees from different backgrounds when brought together in the workplace will necessarily automatically be able to work effectively together. It is critically important to explain that this is not the fault of any one individual, but a reflection of the fact that they will have their own belief systems and values from their own cultural background, which can mean that misunderstandings arise in a multicultural environment. In these situations, organisations as well as individual leaders and line managers must set clear guidance for helping employees to be aware of these potential issues and address them.

4.2 International Work Placements

International work placements are becoming increasingly popular, particularly in large multinational organisations where they wish to understand how business is conducted in different parts of the world. Whilst some multinational organisations have been hugely successful in understanding local marketplaces, others have found it more difficult, and in part this is attributed to the difficulties of understanding local and national culture. Research into employee mobility in respect of international working reveals a number of interesting elements which help us to understand how multiculturalism and international working function in practice.

It is not uncommon for organisations to move employees internationally in order to allow them to learn about different cultures, but also to provide their own advice and expertise in developing areas of the business. However research has consistently shown that for this process to be effective it is far better to send an employee who is flexible and adaptable in terms of understanding differences in culture and communication styles. This is perhaps a surprising finding, as the natural assumption would be to presume that the best technical specialist would be the person to send. But, time and again, research shows that in international working environment, it is much more likely that an international team will be a success if team members have tolerance for different cultures and different communication styles. Whilst technical excellence is of course important, one of the main causes of international project team failure is that team members were unable to communicate effectively with one another because of significant differences in communication style. This is why an understanding of both Hofstede and Lewis is important in a multicultural or international workplace setting. This also explains why there can be challenges in managing international culture.

Q - When someone moves to another country to start a new job, is it their responsibility to put more effort into learning about the new culture in which they work, or the responsibility of the organisation to make them feel welcome?

5.0 Managing Culture

5.1 Practical Steps to Managing Multicultural Teams

Knowing that there are likely to be differences in working and communication styles as a result of cultural beliefs and values, it is critically important that organisations take positive practical steps to create a framework for employees so that they can appreciate and understand possible differences. This might include creating an international induction programme so that overseas employees understand nuances of organisational and national culture. This is sensible because if employees feel disorientated they are unlikely to be productive and effective at work, so it is important to ensure that employees understand basic issues surrounding national and organisational culture.

It is also important for employees from the host country to appreciate that their international colleague may have a different perspective and a different way of communicating. Examples might include people from different cultures being perceived as rude or blunt, which can immediately make effective communication difficult. Host country employees should be reminded that this is likely to be completely unintentional and it is better to be tolerant of possible mistakes in this regard. Being patient and productive in this environment is likely to generate much greater benefit, allowing employees from other backgrounds to bring their knowledge and perspective to the situation.

Obtaining regular feedback from all employees about their views and feelings on working in multicultural teams can help to ‘clear the air’ if there are any misunderstandings or problems. This is why it is better to have employees who have greater flexibility and tolerance, as they are more likely to be patient and offer the benefit of the doubt as well as constructive feedback.

5.2 Changing Culture

Another aspect of managing culture is the recognised difficulties in changing organisational culture. The Johnson and Scholes cultural web model is recognised as being a practical and effective framework which can be easily applied and understood by employees. Organisational change is always likely to be difficult, which is why this is a distinct body of research in its own right. Generally speaking, however, there is agreement amongst academics that in order for change to be effective and become embedded, employees must be involved in the change process themselves and have responsibility and accountability for it. Only in this way are they likely to be committed to delivering the change in whatever form it takes. To achieve this effectively, leaders and managers must set out clear guidance for what they want to achieve in terms of change, and help and support employees in the change process. There is likely to be resistance in the early stages, but if employees understand the purpose of the change and are involved in decision-making, then this is more likely to be effective. Changing the culture of the organisation takes time, particularly given the knowledge that a large proportion of culture is unwritten and not necessarily widely articulated or understood. However, synthesising words and actions is the first step in this process, and essential to form the foundation of successful cultural change within organisations.

Need Help With Your Business Assignment?

If you need assistance with writing a business assignment, our professional assignment writing service can provide valuable assistance.

See how our Assignment Writing Service can help today!

6.0 Summary

This chapter has discussed the subject of organisational culture, presenting a number of key models and theories about identifying and measuring culture, and also classifying it. Culture can be present in many different ways, and there is a relationship between organisational culture and national culture which has implications for contemporary business which is characterised by globalisation and international trade. It is important for managers and leaders within organisations to understand the type of culture which the business has, and also whether this is likely to help them achieve organisational goals and objectives. If not, introducing organisational change is likely to be necessary and this can be enacted through cultural models, but, it is a process which is resource intensive and likely to take time. However, culture is vital to organisational activity as without culture and organisation is likely to lack vision and direction and may well find itself in a difficult situation.

7.0 References and Further Reading

7.1 References

Bower, M. (2003). Company philosophy: 'The way we do things around here' [online] available at http://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/leadership/company-philosophy-the-way-we-do-things-around-here retrieved 11th Jan 2017.

Deal, T. E., and Kennedy, A. A. (2000). Corporate cultures: The rites and rituals of corporate life. London: Da Capo Press.

Handy, C. B. (1996). Gods of management: The changing work of organisations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hofstede, G. (2017). Geert Hofstede Institute [online] available at https://geert-hofstede.com/ retrieved 11th Jan 2017.

Landy, F. J., and Conte, J. M. (2016). Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organisational Psychology. London: John Wiley and Sons.

Lewis, J. (2006). Cultural studies: The basics. London: Sage.

Lewis, R. D. (1999). Cross cultural communication: A visual approach. California: Transcreen Publications.

Reiss, R. (Oct 2012). For Top CEOs, Culture Drives Value Creation [online] available at http://www.forbes.com/sites/robertreiss/2012/10/10/for-top-ceos-culture-drives-value-creation/#69b7a06832cc retrieved 11th Jan 2017.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organisational culture and leadership. London: John Wiley and Sons.

Scholes, K., and Johnson, G. (2002). Exploring corporate strategy. London: Prentice Hall International.

7.2 Further Reading

Kotter, J. P. (2008). Corporate culture and performance. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Schein, E. H. (2009). The corporate culture survival guide. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Trompenaars, F., and Hampden-Turner, C. (2011). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business. Bristol: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

8.0 Case Study

Expert Engineering Ltd (EEL) is a medium-sized specialist engineering firm based in Newcastle upon Tyne. They design and manufacture component parts for transport engineering services such as cabling and signals. The firm is successful and has an agile culture which could be considered as either a Power Culture under the definition proposed by Handy, or a Bet-Your-Company culture under the definition proposed by Deal and Kennedy. The founder of the organisation is still very much hands-on as an engineer, and enjoys designing and developing products and solutions himself, as well as gaining feedback from customers and thinking of innovative solutions to issues. There is a generally friendly and professional feel to the organisation. For example, individual employees’ birthdays are recognised and celebrated - these employees are free to take an additional day off if they wish - and there is a relaxed dress culture on Fridays. However, some employees struggle with the rapid changes in decision-making and the loose (and occasionally chaotic) approach to administration which makes their jobs much more difficult. The business is in no way unsafe but the focus is always on innovation and development and less so on ensuring that in the words of the founder ‘the boring but necessary’ paperwork is done.

EEL have a successful international reputation because of the bespoke nature and high quality of the products that they produce. EEL has won a number of national and international awards for their design and also effective project management of technically demanding solutions. They have been exporting internationally for a number of years found that there is growing demand for their products and services around the world. As such, the founder of EEL thinks it would be appropriate to begin to recruit employees from other countries and backgrounds in order to understand their approach to engineering and design, and also to gain insight into what would be effective in other countries.

There are mixed opinions on this proposed strategy within EEL, with some employees being very supportive of the idea of introducing new perspectives and new talent to the organisation, and others being concerned about how people from other backgrounds and cultures will fit into the ‘unique’ culture of EEL. The employees who express concerns are worried about people from other cultures thinking that the founder is a typical representation of cultural norms, as although the founder is highly charismatic, innovative, and successful, he is also known to have sudden changes of mood and also temper and has been known to shout at other employees. This is tolerated within the organisation, as many employees have worked there for a long time and recognise that this is merely the business owner ‘blowing off steam’. This is part of his personality and communication style, and that he will apologise in due course. The Human Resources (HR) manager is particularly concerned about this, but recognises that the founder of the business is essential to its ongoing success.

The decision is reached that an agency should be used to find a shortlist of potential engineers from overseas who would be a good fit for the organisation, taking into account its culture, and also what is known about the founder of the business. The HR manager department is also keen to introduce an induction programme to make sure that any new employees understand the culture of the business and are able to communicate effectively, and that they feel happy in the new working environment. However, they are unsure about how best to manage the issue of introducing new employees from different cultures to the founder and managing director. There is no simple solution to this problem and they are seeking your advice.

Questions:

- How would you categorise or classify the culture of EEL?

- What do you think is good and bad about the culture of EEL?

- What advantages and disadvantages can you see in recruiting new engineers from international backgrounds?

- What advice would you give the HR manager in regards to a) inducting new employees from different backgrounds and b) helping existing employees integrate with existing organisational culture?

- Do you think the culture of EEL needs to change, if so how?

- What you think would be the implications of changing the culture of EEL?

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: