Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Lecture

“Corporate Social Responsibility is one of the greatest global challenges of the 21st century. [The way businesses are run and regulated] need[s] revisiting and even recasting for the sake of our generation, our descendants and the planet’s future”

- (Horrigan, 2010: ix)

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an issue of much debate and discussion within modern business. There are those that argue that CSR efforts are vital if environmental and social challenges (such as climate change, labour exploitation and good governance) are to be effectively addressed. Others believe that the CSR agenda has been used by big multinational entities to maintain exploitative business models whilst still appearing to be responsible organisations.

This chapter will introduce and outline the key CSR concepts and theories. Both the perceived benefits and the stated criticisms will be discussed in order to help the reader develop the case both for and against CSR. In building a more comprehensive understanding of this contested concept, a critical review of business practices and their impact on the workplace, communities, the environment and wider markets can subsequently be undertaken.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

To be able to:

- Define Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

- Outline the CSR responsibilities of business and the theories applied.

- Understand a range of CSR methodologies.

- Present both the perceived benefits of CSR and the criticisms applied.

2.0 WHAT IS CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY?

“Corporate Social Responsibility is a recognition that organisations need to take account of the social and ethical impact of their business decisions on the environment in which they compete.”

(Henry, 2011: 50)

“[It is] the commitment by organisations to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as the local community and society at large.”

Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin & Regnér, 2014: 127)

Legislative and regulatory frameworks outline the operating environment for a business. These are interpreted and applied through the corporate governance and reporting structures that an organisation puts in place to manage these obligations. However, these set only the minimum operating standards expected and the number of major corporate failures over the past twenty years (such as Enron) has shown how these legal and regulatory mechanisms still allowed space for significant corporate irresponsibility (Bakan, 2004).

The size and international footprint of national and multinational entities (particularly when their supply chains are included) means that they will inevitably have a significant impact on society. Whilst many Governments have sought to capture CSR obligations through legislation (such as the Danish Financial Statement Act introducing mandatory reporting requirements in relation to human rights and climate impact), these rarely keep pace with the societal expectations placed on businesses (Danish Business Authority, 2016). As a consequence, CSR is primarily concerned with the way in which businesses seek to exceed these minimal legal obligations.

Get Help With Your Business Assignment

If you need assistance with writing your assignment, our professional business assignment writing service is here to help!

2.1 CORE CHARACTERISTICS OF CSR

-

Voluntary activities that go beyond the corporate obligations outlined in legislation and regulation. This is reflected in the UK Government’s CSR definition:

UK Government and CSR:

“The voluntary actions that business can take, over and above compliance with minimum legal requirements, to address both its own competitive interests and the interests of wider society.”

(Crane, Matten & Spence, 2008: 6)

- The development of self-regulation initiatives by businesses (and/or representative trade bodies) to recognise emerging societal concerns and norms. Examples include the rise of “Fair Trade Partnerships” seeking to offer disadvantaged producers the opportunity to move out of extreme poverty through access to markets under beneficial rather than exploitative terms (Nicholls & Opal, 2004).

- Managing externalities. Externalities are both the positive and negative effects of economic behaviour borne by those outside of the business. Examples include pollution (such as the direct health impact on workers and the communities surrounding a business) and human rights. Legal sanctions can be applied (such as pollution fines), but CSR approaches seek to ‘internalise’ these issues i.e. investing in modern technology to prevent pollution at source.

- A broad stakeholder approach. Rather than simply reflecting direct shareholder interests, CSR considers how a company must also engage the other agencies that are core to its continued profitability. The concerns of a diverse community (including consumers, communities, special interest groups, suppliers and employees) must be captured. This approach and the extent to which the broader, more ethical concerns of stakeholders is balanced against the more specific interests of shareholders is a key characteristic of debates surrounding CSR.

- Aligning social and economic responsibilities. Maintaining a good reputation is good business and this sits at the heart of any business case for CSR. Profit on a sustainable basis, (rather than profit at any cost) underpins this alignment.

- Many businesses develop a set of core values and beliefs that capture their approach to CSR, developing a philosophy that sets clear social and ethical expectations.

- Non-discretionary. Rather than simple philanthropy (i.e. corporate support or sponsorship of those less fortunate), CSR is tied to all business operations. The concern is about how core functions such as procurement, production, logistics and human resource management affect society.

(Crane et al, 2008: 4-9)

Ultimately, with increased public criticism of corporate actions and concerns over ethical sourcing and environmental impact, an organisation that actively pursues a socially responsible strategy can enhance their corporate reputation. This, in turn, can both build and sustain a competitive advantage.

3.0 THE RESPONSIBILITIES OF BUSINESS

Depending upon their view of competitive positioning a business can adopt or consider a range of attitudes towards CSR. These can include:

- An extreme view (which can be argued to have led to the major corporate failures of the last twenty years) is the ‘laissez-faire’ approach. Here the focus is on legal compliance built around the maximisation of profit, payment of taxes and the provision of employment. CSR is seen as being an issue for lower/middle management (at best) and the company is likely to be defensive when challenged by external agencies about CSR concerns. External stakeholders are ‘briefed’ rather than engaged (if at all). CSR is not a core issue for the leadership of the business.

- Enlightened self-interest. CSR is seen as a market opportunity given the interests of consumers and competitors. Leaders therefore support the introduction of business systems to capture good practice and are prepared to interact with a broader stakeholder community. When external CSR pressures are experienced (such as consumer concerns over the treatment of suppliers), the company will react to maintain its markets and competitive positioning.

- Stakeholder interaction. Sustainable business practices are seen to be critical to the maintenance of any competitive advantage. Companies therefore set clear targets that are not limited to economic aspects (such as market share) - environmental and social objectives reflecting broader CSR concerns are also included. This is often referred to as the ‘triple bottom line’ (see 4.3). CSR is considered to be a Board-level issue, with comprehensive reporting/monitoring structures and the leadership are seen/required to act as CSR ‘champions’. This proactive approach is often reflected in the development of a partnership approach to stakeholder engagement.

- Shaper of society. The rationale for the business is likely to be built around social and market change, placing CSR considerations at the heart of the business model. CSR is seen as being both an individual (employee) responsibility as well as a corporate concern, which is likely to be reflected in the values outlined for the organisation. The business is likely to build numerous multi-organisational alliances involving stakeholders to shape and develop the CSR agenda. As a consequence, the leadership is often considered to be inspirational or visionary as they seek to articulate the ‘better future’ proposed within the business strategy.

Discussion Point:

The role of business is to serve the best interests of shareholders. Friedman (1962) argued that there is only one social responsibility of business - to use resources and carry out activities that maximise profits within the rules set for fair and open competition.

- Do you agree?

- To what extent is the importance of CSR shaped by the objectives set for the business?

Two key philosophies capture the fundamental differences in CSR attitudes and approaches - shareholder value theory and stakeholder theory

3.1 SHAREHOLDER VALUE THEORY

Shareholder Value Theory (SVT) builds on Friedman’s view (outlined above) in that making profits is the overriding corporate purpose and that social activities (outside those set in law such as pollution control or minimum wage legislation) should only be considered if they contribute to increasing shareholder value.

SVT is underpinned by Agency theory, where the owners (shareholders) are seen as the principal and the managers act as their agent (Ross, 1973). These managers owe shareholders (as the providers of business capital) a ‘fiduciary duty’ to maximise profitability. As a suitable incentive, the economic interests of these managers are often closely aligned to those of the stakeholders (e.g. through salary and bonus payments linked to share value).

The core SVT argument is that the market is superior to individual organisations when allocating resources and that with the manager acting as agent improved financial performance can be achieved. The market, through shareholders, acts as an effective mechanism to incentivise managers appropriately. Where managers ‘fail’ (i.e. if the market perceives that they could secure better financial returns) mergers and takeovers result.

As a consequence, it could be argued that CSR is a significant threat to SVT as it introduces broader concerns. However, the theory can be seen to balance these potentially competing interests when social responsibilities can be turned into business opportunities. It is this aspect that moves attitudes from the stark ‘laissez faire’ approach to one of more enlightened self-interest (as outlined above).

“The proper social responsibility of business is to tame the dragon. That is, to turn a social problem into economic opportunities and benefit, into productive capacity, into human competence, into well-paid jobs and into wealth.”

(Drucker, 1984: 62)

Given the nature of past corporate failings and the resultant reputational damage, it is now generally accepted that in some cases meeting certain social interests can contribute to maximising shareholder value. Most large companies pay significant attention to CSR, publishing appropriate strategies and targets. This has also supported the emergence of the concept of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility (SCSR).

SCSR attempts to focus on those CSR activities that yield substantial business-related benefits, with any measures pursued having to demonstrate how they support core corporate objectives. In essence, a clear cost-benefit analysis is required (Crane, McWilliams, Matten, Moon & Siegel, 2008). However, such attempts to develop an ideal or appropriate level of CSR (i.e. one that still maximises shareholder value) can be seen as cynical and self-serving by the broader stakeholder community.

3.2 STAKEHOLDER THEORY

“Stakeholders are those individuals or groups which affect or are affected by the achievement of an organisations objectives.”

(Henry, 2011: 162)

“Those individuals or groups that depend on an organisation to fulfil their own goals and on whom, in turn, the organisation depends.”

(Johnson et al, 2014: 107)

Stakeholder Theory argues that a business should be managed for the benefit of a much broader stakeholder base, including entities such as customers, suppliers, employees, communities and relevant special interest groups (such as Trade Unions and environmental charities) as well as shareholders. In protecting the legitimate interests of stakeholders, the leadership of a company is also protecting future business competitiveness by recognising and understanding the environment it operates within.

Seven principles of stakeholder management have been proposed:

- Managers should acknowledge and monitor the concerns of all legitimate stakeholders, taking their interests into account when making decisions and conducting business operations.

- Managers should effectively engage stakeholders about their concerns and contributions and the risks they assume through their involvement in the business.

- Business processes and behaviours should consider the concerns and capabilities of each stakeholder group.

- There should be a fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of corporate activity between stakeholders, taking into account their capabilities, risks and vulnerabilities.

- Managers should work cooperatively with stakeholders to ensure that any risks or harm arising from company actions are minimised (with appropriate compensation if necessary).

- Corporate activities that prejudice inalienable human rights (such as the right to life) are clearly unacceptable to all stakeholders and must be avoided altogether.

- Managers need to acknowledge the conflicts that can exist between their own role (as corporate stakeholders) and their legal and moral responsibilities to all stakeholders. Issues should be openly addressed involving third parties where necessary.

(Clarkson Center for Business Ethics, 1999).

Diagram 1 provides an illustrative stakeholder ‘map’ for Starbucks Inc., highlighting the interest and concerns that the company needs to consider:

DIAGRAM 1: STARBUCKS STAKEHOLDERS

|

Stakeholder(s) |

Interest and Influence |

|

Primary |

-internal to Starbucks |

|

Staff. |

The front face of the company to customers. Will wish to work for an entity that reflects their own moral and social views whilst feeling valued and fairly rewarded. Will wish to reflect Starbucks CSR focus in their engagement with customers |

|

Management. |

As staff, but will wish to be reassured that CSR focus is ‘genuine’ and not just a marketing or business positioning tool. Likely to take a greater interest in supply chain impact(s) |

|

Primary |

-external to Starbucks |

|

Business institutions, markets and shareholders |

Whilst recognising that CSR and ethical approach delivers critical differentiation (and therefore market growth potential) for consumers, they will wish to ensure that the model delivers enduring financial returns and secured profitability. |

|

Customers |

Provide revenues for Starbucks. Whilst they may be prepared to pay a premium for Starbucks services in order to support CSR/ethical aims, this will need to be underpinned by quality products and services that meet their immediate/personal needs. |

|

Competitors |

Most entities have recognised the importance of sustainability in terms of both business reporting and customer expectations. Will therefore seek to erode Starbucks competitive positioning and market share by mirroring their CSR approaches and therefore erode any perceived differentiation. |

|

Suppliers |

Suppliers and supply chain seen as integral to Starbucks success and CSR focus. Engaged in product/service development - ethical engagement (rather than a pure margin/profitability focus) supports competitive differentiation and growth. |

DIAGRAM 1: STARBUCKS STAKEHOLDERS (CONTINUED)

|

Stakeholder(s) |

Interest and Influence |

|

Secondary |

-internal to Starbucks |

|

Staff representation groups such as Trade Unions. |

Whilst supporting Starbucks CSR agenda, will wish to ensure that the sustainability focus also protects the interests of their members as well as the supply chain. |

|

Staff social interests and CSR awareness |

Whilst employees may not initially join Starbucks because of its ethical and sustainability policies, the culture created does drive attitudes and behaviours in the workplace. |

|

Secondary |

-external to Starbucks |

|

National Governments and International Trade Bodies. |

Starbucks will wish to inform and influence Government policies that shape their supply chain (e.g. workers’ rights). Government will wish the company to be as successful as possible, as it generates employment and (local) tax revenues |

|

Non-Social stakeholders groups. |

Pressure groups seeking to drive/support CSR agendas will be prepared to both champion Starbucks successes whilst also highlighting any failures (which could undermine positioning if significant supply chain/ethical failings are identified). |

|

Media and Academic Commentators |

Following significant business failings (notably within the banking sector), CSR and sustainability issues are routinely reported upon generating greater social/customer awareness. |

4.0 CSR METHODOLOGIES

Get Help With Your Business Assignment

If you need assistance with writing your assignment, our professional business assignment writing service is here to help!

4.1 PHILANOTHROPY

Whilst it can be difficult to distinguish between individual and corporate philanthropy (the desire to promote the welfare of others), at the time of the industrial revolution many business leaders developed social and environmental interventions that supported workers and their communities. Examples include the provision of better quality housing, hospital clinics, lunch-rooms and recreational facilities. Many early business leaders also exercised their philanthropy by supporting the arts, education and religious communities.

These early philanthropic approaches were often challenged given the prevailing business attitude (captured by SVT and Agency Theory). Corporate philanthropy (such as providing workers access to libraries and education) was seen as exceptional and rooted in the ideals and values of respected individuals rather than as a core business objective.

In the modern era, corporate philanthropy (the more discretionary aspect of CSR) is more easily recognised, particularly when a business supports an activity, charity or community that provides no perceived direct business benefit. However, this philanthropy can be shaped by two distinct issues - corporate reputation and the composition of the Board and/or the senior leadership.

Discussion Point:

Philanthropy and Corporate Reputation

In the UK over the past ten years, extensive business sector support in terms of funding, sponsorship and facilities has been provided to Help For Heroes - a charity focussed on the care and rehabilitation of injured military personnel and veterans. The organisation developed a considerable media presence and support from all sectors of society.

Many companies without any direct business interest in the military, defence sector contracts or the provision of assistance to veterans supported Help For Heroes. Is this Corporate Philanthropy or enlightened self-interest given the marketing, promotional and reputational aspects seen by consumers? Can it be both?

Corporate philanthropy can be driven by the interests of Directors and the senior leadership of the Board. Those with a strong personal commitment to socially responsible causes are more likely to support corporate philanthropy that has no direct business benefit, even where it decreases profitability or adversely affects cash flows.

Corporate philanthropy is also used as a mechanism to create a binding ethos and develop corporate values shared by all employees. In such cases, all employees are invited to suggested a cause that the business should support through fundraising efforts etc., with no requirement to link proposals to direct business benefit.

4.2 SUSTAINABILITY

Corporate sustainability concerns the processes by which enterprises manage their economic, environmental and social obligations and opportunities to create long-term competitive advantage and growth (often referred to as people, planet and profit) (PwC, 2015). In essence, sustainability is about meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Nemetz, 2013: 7).

Studies have highlighted common conceptual threads surrounding corporate sustainability and sustainable development:

- The concept of natural capital where it is essential to maintain a constant and renewable resource base, along with the environment that sustains it.

- A focus on social stability, empowerment and equity - often with an emphasis on reducing poverty and maintaining an adequate way of life for all citizens across the world.

- Addressing development rather than growth. For example, utilising technology to improve sales and services, rather than simply increasing the consumption of resources.

- The precautionary principle. This is a basic recognition that business practices must change now to protect the global ecosystem rather than wait for definitive proof (when it may be too late to act or reverse the effects e.g. pollution).

The central idea of sustainability is that the current generation must leave the next generation a stock of capital (e.g. raw materials) that is no less than that which exists now. Businesses should live off the ‘interest’ generated by the existing resource base rather than consume it.

(Nemetz, 2013).

Case Study: CSR and Sustainability - the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)

Uncontrolled felling of trees for commercial use threatens the flora and fauna of the local environment. Whilst individual companies may consider limiting their impact, the reality is that they may distrust the activities of others and therefore cut all they can before ‘others’ destroy the forest.

A system of national and international laws exist to prevent deforestation - but it still continues at a rapid pace. Where corporate CSR attempts to address sustainability fail (even when reinforced by legislation), then multi-party movements and pressure groups (often built around NGOs) can emerge to drive the sustainability agenda.

The FSC (formed in 1993) involves many entities (such as the World Wildlife Fund and Greenpeace) - including timber companies - and sets standards for both sustainable forestry as well as air and water quality protection measures. Whilst the FSC is an international group, membership is voluntary and its powers of enforcement are weak. Despite these limitations, it has been very effective at improving levels of sustainable forestry within businesses.

Through a system of transparent certification and labelling that is clearly understood by consumers, the FSC is able to effectively ‘shame’ non-compliant companies, damaging their corporate reputations and sustain consumer boycotts. Consumers can receive trusted assurances where responsible forestry has taken place and avoid those products that are seen to be ‘harmful’ to the environment.

As a result, meeting FSC sustainability standards is now seem as a critical corporate objective and success factor for most forestry businesses. The FSC, rather than legislative and regulatory processes, has driven the CSR strategies and sustainability practices of major companies.

(Craig-Smith & Lenssen, 2009: 258-259)

4.3 THE TRIPLE BOTTOM LINE

Sustainability is comprised of three core elements - social, environmental and economic, generally expressed as ‘people, planet and profit’ (see above). As noted earlier, the argument is that businesses must look not only at profit and loss but also measure their impact on both the environment and broader society.

This ‘triple bottom line’ approach becomes more important when it is considered how modern companies are not just held accountable by their shareholders, legislative measures and industry regulation. Stakeholders will introduce measures of environmental and social success which can affect competitive positioning, reputation and profitability, even if the company does not.

As a result, almost all of the world’s major corporations report on CSR, with business targets that include both social and environmental objectives. This reporting of the ‘triple bottom line’ demonstrates how CSR should no longer be seen as optional when developing a successful corporate strategy.

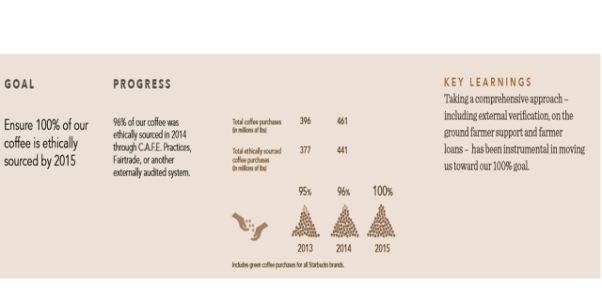

Diagram 2: Starbucks progress report on the ethical sourcing of coffee - recognising the ‘triple bottom line (Starbucks, 2014).

5.0 BENEFITS OF CSR

5.1 ETHICAL PERSPECTVIES

Business ethics should address three core issues:

- The values that underpin the way business is done - often expressed in terms such as honesty, integrity and fairness.

- Outlining a code or set of principles that brings together these values into a clear standards statement e.g. outlining acceptable staff behaviours.

- A corporate governance structure that ensures that people and business practices are effectively monitored to ensure compliance with the published principles or code of ethics.

The Institute of Business Ethics (IBE) states that an organisation cannot be genuinely “responsible” without an embedded and inherent culture that is based on ethical values such as trust, openness, respect and integrity (Hopkins, 2016: 84). The IBE therefore believes that a distinction can be drawn between ethics - the way of doing business - and CSR which could be stated to focus on outputs - what is done.

However, it is argued that such a spilt between CSR and ethics is artificial. A company is unlikely to be able to operate on truly ethical principles if the nature of its business is damaging to the environment and/or ignores the social welfare of the communities it engages with (e.g. working conditions for people from less developed countries). Ethical codes and principles in an era of globalisation are not limited to the one company and governance structures and underpinning commercial mechanisms often extend these obligations into the supply chain.

CSR has therefore provided a mechanism to link corporate ethical aspirations and standards to clearly articulated and measurable business objectives. This is further reinforced by the adoption of voluntary standards and the creation of trade bodies that use CSR reporting mechanisms to introduce more ethical concerns into supply chain practices.

Fair Trade Partnerships provide a good example of how these more ethical concerns form core elements of some CSR strategies adopted. Such ethical CSR approaches can also create a social dynamic that delivers a direct business benefit. For example, Starbucks customers see the consequences of their coffee purchasing choices, noting that they are helping to make a positive and enduring difference to disadvantage producers (Johnson et al, 2014). As a result, Starbucks more ethical CSR approach delivers a critical point of business differentiation helping to generate an enduring competitive advantage.

5.2 THE SOCIAL CONTRACT

Business ethics proposes the concept of a fair and efficient ‘social contract’ between a company and its stakeholders. This is not a written document, but an ideal relationship rooted in concepts of justice, rationality and built around the development of a consensus. If a company can maintain a good reputation then this means that stakeholders have confidence in both its operations and the way relationships are managed.

The basic tenets of CSR reflect the core conditions of any social contract i.e.

- The interests of all parties are at least consideration.

- All stakeholders are kept informed and not deceived.

- Agreements are reached on a rational and voluntary basis.

- No stakeholders have suffered, been constrained by corporate actions or subjected to unfair power relationships.

Maintaining such a social contract generates key benefits:

- The resulting corporate standards will counteract conduct that could harm legitimate stakeholder expectations of ‘well-being’. For example, a major retailer using its corporate size to intimidate suppliers and manipulate relationships is likely to suffer significant reputational damage. A social contract approach would focus on partnerships rather than a purchasing power relationship.

- If the trust associated with a functioning social contract exists, then governance and monitoring costs are likely to be lower. For example, trust across businesses supports the development of cheaper, more efficient quality assurance partnerships rather than a reliance on intensive quality control and inspection regimes.

- The negative social effects of any corporate activities are highlighted more rapidly (thus minimising downstream costs associated with rectification or restoring business reputation). A social contract approach means that the company is not focussed just on basic compliance issues - legitimate stakeholder interests are also addressed. Emerging social and environmental concerns are therefore less likely to be overlooked and corporate reputation will be protected.

5.3 THE BUSINESS CASE

Many businesses are able to create a clear financial case for CSR, built around the understanding that by doing the ‘right’ thing for their stakeholders they will, in turn, be doing the right things for the business. These arguments can be presented as follows:

- Cost and Risk Reduction. The CSR business case is built around an appreciation of how stakeholders can present possible threats to the business and that its economic interests are best served by mitigating them through social and environmental performance measures. Effective CSR approaches can help avoid/prevent expensive issues such as consumer boycotts and legal liability disputes (e.g. for environmental damage).

- Competitive Advantage. In this context, stakeholder CSR concerns are not seen as constraints but as opportunities to be leveraged. For example, Starbucks vision and value statements outline how the ethical and sustainability position of the company provides a key point of differentiation and competitive advantage. Starbucks CSR focus delivers impressive returns - in 2013, the Company served more than 3 billion customers through over 19,000 stores in 62 countries, delivering revenues of $14.9Bn (Starbucks Annual Report, 2013).

- Reputation. An enduring competitive advantage is secured by enhancing and protecting the reputation and legitimacy of the company through well-publicised CSR policies and objectives. Companies will seek social or environmental certification (such as FSC and Fair Trade Partnerships) in order to develop their business positioning and access to markets (and therefore future sales and profitability) in the minds of both consumers and the wider supply chain.

- Synergistic value creation. This challenges the traditional interpretation of value being limited to one company. The intent is to create ‘win-win’ business outcomes by engaging numerous stakeholders (such as those in the supply chain) to develop shared CSR approaches and linked objectives. Examples could include developing a shared packaging standard between all businesses in the supply chain, thus reducing direct and redundant costs whilst also meeting environmental CSR objectives.

6.0 CRITICISMS OF CSR

Numerous criticisms of CSR exist:

6.1 CSR IS A PUBLIC RELATIONS EXERCISE

CSR is a marketing exercise focussed on brand image and public relations by appealing to consumer conscience and public desires to ‘do good’. CSR has even been described as a corporate approach to co-opt and constrain the environmental movement. When challenged by environmental activists on some of its CSR statements, Nike and other major US business interests argued that ‘if a company’s claims on human rights, environmental and social issues are legally required to be true, then companies won’t continue to make statements on these matters’ (Corporate Watch, 2016).

At the very least, corporate CSR reporting introduces mixed motives - are CSR activities undertaken purely to make the company look better in the eyes of the consumer, or does a more altruistic drive exist which subsequently improves competitive positioning when it is noted and appreciated by stakeholders?

Discussion Point:

Examine the CSR reporting of two or three multinational companies. Are these reports about marketing and ‘spin’ or are they really driven to meet their CSR objectives?

What is the balance between looking ‘good’ and doing ‘good’? Is it wrong to use CSR achievements to improve the competitive position of a company?

6.2 AVOIDING REGULATION

The importance of voluntary activity as one of the core characteristics of CSR has already been highlighted (2.1). However, the initial early drivers behind CSR reporting were mandatory, with the introduction of legislative requirements for businesses forcing them to address issues such as emissions control and financial management standards.

It could therefore be stated that corporate CSR efforts are therefore a mechanism to avoid the introduction of further legislation and regulation. Mandatory standards setting and reporting introduces increased costs and can even undermine competitive advantage. If all companies have to do meet the same production requirements, then how can they differentiate? There is also a more fundamental corporate argument - is it possible to regulate ethics?

Companies would prefer the freedom to set their own CSR standards as this maintains competitive tension (through differentiation) and minimises Government interventions through legislation. However, it is interesting to note how the increasing importance of CSR considerations to consumers is beginning to challenge this position. As companies respond to customer requirements for ‘greener’, more ethically sourced products and services, some are actively seeking more regulation to control/minimise competition from less scrupulous business entities

6.3 UNDERMINING THE CORE AIMS OF BUSINESS

Building on the views of Friedman (1962) and SVT, it is argued that CSR activities undermine business efficiency. If it is accepted that the core aim of business is to be profitable then diverting resources to address CSR concerns is wasteful unless it is necessary to remain within legislative bounds that affect all competitors.

This argument of efficiency is further compounded when supply chain issues are considered. A company’s CSR possible may address issues of working conditions, environmental concerns and equality within its own business premises, but is it appropriate to use shareholder resources to attempt to address the same issues within outsourced services and the wider supply chain?

The practicalities and difficulties of any corporate Board attempting to identify and manage the significant and diverse number of stakeholder relationships is also a challenge. Unless some form of limit is placed on the breadth of any CSR policy (e.g. how far corporate values should be extended into the supply chain), then CSR relationship management rather than profitability drives business.

6.4 REINFORCING CORPORATE POWER

The drive for comprehensive CSR approaches is undermining the balance between democracy (the ideals of the citizen) and capitalism (the needs of the consumer). The voluntary, self-regulatory components of CSR when linked with the increasing power and influence of multinational entities (fighting against unwanted regulation) erodes the impact of public policy (Reich, 2007).

In essence, CSR has now become a corporate tool, as businesses seek legislation and regulation that provides them with a distinct advantage in relation to their competitors.

6.5 UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Businesses now strive to demonstrate their corporate global citizenship through their CSR strategies. However, in doing so the power and influence that large multinationals can exercise threatens prosperity in poorer, less-developed countries by reducing competition, undermining local market economies (Henderson, 2001). Henderson (2001), described this as ‘misguided virtue’.

Case Study: Child Labour in the Football Industry - Sialkot, Pakistan

The Sialkot region of Pakistan supplies around 70% of the world’s footballs - approximately 35 million every year. In the 1990’s, campaigners used the Euro 96 football championships to highlight the issues of child labour in the region, pressurising major brand names in the industry to reform their supply chains.

Companies worked with UNICEF, Save the Children and other key stakeholders to develop a programme that would address the fundamental issues. As a result, 60 manufacturers (responsible for 90% of export production) now agree that no children under 14 will work with them. This is monitored by independent inspectors as well as the international purchasing companies and has supporting initiatives such as education programmes and women’s welfare.

Whilst this initiative is stated to have benefited over 44,000 local families it has also introduced significant local market problems. The 52 companies outside of this voluntary agreement are not monitored and their ability to continue to employ young children (if they chose to do so) delivers a significant local competitive advantage.

Subsequent studies noted that poverty was not the main driver for child labour in the region. The amount of work available meant that local incomes were almost twice the national average and children took up available work due to the lack of alternative education opportunities. Denying children the opportunity to work without addressing attitudes and access to education simply reduced household incomes.

Concerns have also been raised about the adverse long-term impact on displaced child workers. It is feared that many have now moved into working under more hazardous conditions for the surgical goods companies that are also concentrated in the Sialkot region.

(Sources: Hussain-Khaliq, 2004; UNIDO, 2002; JUDES, 2016)

7.0 SUMMARY

A comprehensive review of CSR theory, practices and concerns has been provided which helps to illustrate some of the complex arguments that exist. Whilst supporting case studies have been included, this chapter should be reviewed in conjunction with some of the current CSR policies and reports provided by major companies.

Get Help With Your Business Assignment

If you need assistance with writing your assignment, our professional business assignment writing service is here to help!

A company’s approach to CSR will consider both the legislative and regulatory obligations that exist in the market and those policies pursued to reflect the values and standards that support the business strategy adopted. As discussed in the previous chapter, CSR is rooted in the desire of both businesses and their customers/consumers to operate in a more ethical manner.

The analytical challenge is to consider if CSR is now just one more facet of corporate competitive advantage. Even if this is the case, some could argue that this is just confirmation that CSR - the business of doing ‘good’ - is now seen as ‘good’ modern business. The rise of companies trading on their ethical position as the source of their competitive differentiation provides a solid foundation to review current CSR approaches and concerns.

What do you believe should form the core components of any corporate CSR strategy?

Should a business use its CSR policies to impose their corporate values on all aspects of their (international) supply chain?

Can business legislation and regulation effectively capture all CSR elements?

7.1 RECOMMENDED TEXTS

Blowfield, M., Murray, A. (2014). Corporate Responsibility, 3rd Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Molthan-Hill, P. (2014). The Business Student’s Guide to Sustainable Management: Principles and Practice, Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing Ltd.

REFERENCES

Bakan, J. (2004). The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, New York: Free Press.

Clarkson Center for Business Ethics. (1999). Principles of Stakeholder Management, Toronto: Clarkson Center for Business Ethics.

Corporate Watch. (2016). What’s wrong with Corporate Social Responsibility?: The arguments against CSR [Online], Available:

https://corporatewatch.org/content/whats-wrong-corporate-social-responsibility-arguments-against-csr [19 October, 2016].

Craig-Smith, N., Lenssen, G. (2009). Mainstreaming Corporate Responsibility, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Crane, A., Matten, D., Spence, L.J. (2008). Corporate Social Responsibility: Readings and cases in a global context, Abingdon: Routledge.

Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., Siegel, D.S. (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Danish Business Authority. (2016). Legislation [Online], Available:

www.csrgov.dk/legislation [18 October, 2016].

Drucker, P.F. (1984). The New Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility, California Management Review, 26, pp. 53-63.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Henderson, D. (2001). Misguided Virtue: False Notions of Corporate Social Responsibility, Wellington: New Zealand Business Roundtable.

Henry, A.E. (2011). Understanding Strategic Management, 2nd Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hopkins, M. (2016). CSR and Sustainability: From the Margins to the Mainstream - A Textbook, Sheffield: Greanleaf Publishing Ltd.

Horrigan, B. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility in the 21st Century: Debates, Models and Practices Across Government, Law and Business, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Hussain-Khaliq, S. (2004). Eliminating Child Labour from the Sialkot Soccer Ball Industry, Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 13, pp.101-107.

Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D., Regnér, P. (2014). Exploring Strategy: Texts and Cases, 10th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

JUDES. (2016). Sports Balls: Learning About Fair Trade [Online], Available:

http://www.judesfairtrade.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Sports-Balls-Case-Study_FT-A-Better-Deal.pdf [20 October, 2016].

Nemetz, P.N. (2013). Business and the Sustainability Challenge: An Integrated Perspective, Abingdon: Routledge.

Nicholls, A., Opal, C. (2004). Fair Trade: Market-Driven Ethical Consumption, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

PwC. (2015). Moving from compliance to leadership [Online], Available:

http://www.pwc.com/us/en/technology-forecast/2011/issue4/features/feature-sustainability-as-normal-business.html [18 October, 2016].

Reich, R.B. (2007). Supercapitalism: The Transformation of Business, Democracy, and Everyday Life, New York: Random House Inc.

Ross, S. (1973). The Economy Theory of the Agency: The Principal’s Problem, American Economic Review, 63, pp.134-139.

Starbucks. (2014). Global Responsibility Report, Seattle: Starbucks Coffee Company.

Starbucks Annual Report. (2013). Starbucks Corporation Fiscal 2013 Annual Report, Seattle: Starbucks Coffee Company.

UNIDO. (2002). Corporate Social Responsibility: Implications for Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries[Online], Available:

http://www.unido.org/fileadmin/import/userfiles/puffk/corporatesocialresponsibility.pdf [20 October, 2016].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blowfield, M. (2013). Business and Sustainability, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CQ Researcher. (2010). Issues for Debate in Corporate Social Responsibility: Selections from CQ Researcher, California: Sage Publications Inc.

Visser, W., Tolhurst, N. (2010). The World Guide to CST: A Country-by-Country Analysis of Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility, Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing Ltd.

Cite This Module

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: