VRIO analysis guide

Info: 4414 words (18 pages) Study Guides

Published: 25 Sep 2025

Struggling with a VRIO analysis or another management assignment? Our MBA-qualified management writers can create a bespoke model answer, tailored to your brief and written to the grade you order. Get the guidance you need – see our management assignment help page.

Strategic planning requires a balance of external and internal analysis. While tools like PESTLE and Porter’s Five Forces examine the external environment, internal analysis focuses on a firm’s own resources and capabilities.

VRIO analysis is a key internal tool – alongside frameworks such as the value chain and SWOT – that helps organisations identify which resources can lead to competitive advantage.

Developed as part of the resource-based view of the firm, VRIO stands for Value, Rarity, Imitability, and Organisation (Barney, 1995). It offers a structured way to evaluate a company’s assets and skills to see if they can be sources of sustained success.

In essence, VRIO analysis asks four critical questions about any significant resource or capability:

- V – Is it valuable?

- R – Is it rare?

- I – Is it difficult to imitate?

- O – Is the firm organised to capture its value?

By systematically answering these questions, managers can pinpoint internal strengths that give their company an edge over competitors (Barney, 1991). Therefore, VRIO provides a rigorous lens to examine why some firms perform better than others based on what they own or do uniquely well.

The VRIO framework explained

The VRIO framework breaks down the assessment into four dimensions. Each dimension highlights a condition that a resource or capability must meet to yield an advantage.

Importantly, all four criteria should be satisfied for a sustained competitive advantage. If any factor is missing, the advantage may be temporary or non-existent (Barney, 1995).

The following sub-sections explain each VRIO criterion, with management-friendly examples to illustrate the concepts.

Value

A resource is valuable if it enables the firm to exploit opportunities or neutralise threats in the marketplace. In practical terms, a valuable resource helps a company increase customer value either by raising product differentiation, improving quality or efficiency, or by lowering costs (Jurevicius, 2025).

For example, Apple’s brand equity clearly adds value. It allows Apple to charge premium prices and secure customer loyalty, enhancing the perceived worth of its products. This strong brand contributes to Apple being one of the most valuable companies globally. In fact, Apple’s brand was recently valued at over $574.5 billion, reflecting how much competitive value it generates (Brand Finance, 2025).

A resource that does not add value, however, puts the firm at a disadvantage. It incurs costs without contributing to customer benefit or strategic goals. Thus, the first VRIO question filters out resources that are not strategically useful. Only those assets or capabilities that improve the firm’s position – by increasing revenue, reducing costs, or bolstering customer satisfaction – qualify as valuable.

Rarity

Rare means that a resource is scarce relative to demand: few (if any) other competitors possess it. If a valuable resource is also rare, it can be a source of temporary competitive advantage until others acquire or develop it. Conversely, if most competitors have a similar valuable resource, it leads to competitive parity. The resource becomes a basic requirement rather than an advantage (Jurevicius, 2025).

For instance, Tesla’s battery technology capabilities were rare in the automotive industry when Tesla first pioneered long-range electric vehicles. This early investment in superior battery design and manufacturing capacity gave Tesla a unique capability that competitors lacked (Santini, 2024).

Because few rivals could match its battery efficiency and scale at the time, Tesla enjoyed a significant head start. By contrast, resources like general IT systems or common industry skills – however useful – are often widely available and therefore do not confer uniqueness.

While these common capabilities must not be neglected (since a firm would fall behind without them), they are unlikely to create an edge over competitors. In VRIO analysis, identifying truly rare resources is crucial. Rarity combined with value is what elevates a strength into a potential competitive advantage.

Imitability

The third criterion asks about imitability – whether the resource is hard to imitate or substitute. Even a valuable, rare resource only yields a sustainable advantage if competitors cannot easily copy it or find an equivalent alternative (Barney, 1991). If a resource can be acquired or duplicated cheaply by others, any advantage will quickly erode.

Resources may be costly to imitate for several reasons. Some have unique historical development or deep accumulation over time that rivals cannot recreate. Others benefit from legal protection (e.g. patents) or involve tacit know-how that competitors struggle to obtain.

Many advantages often stem from complex social systems or culture that outsiders cannot replicate (Barney, 1995). A classic example is Coca-Cola’s secret formula and brand reputation – competitors find it practically impossible to duplicate these intangible assets.

Similarly, in a technology context, one reason Tesla’s battery capability remained hard to imitate (at least for a number of years) was the combination of proprietary knowledge, manufacturing integration and learning that Tesla achieved. Competitors found it challenging to catch up quickly because replicating Tesla’s battery efficiency and production scale required massive investment and time.

Generally, if a competitor can simply buy or build a similar resource, it fails the inimitability test and any advantage will be short-lived. Truly inimitable resources often involve unique innovation, cumulative experience or high complexity. When a resource is valuable, rare and inimitable, it can provide a strong competitive advantage. However, this holds only if the firm is also organised to exploit it. Organisation is the final VRIO element.

Organisation

Even a resource that is valuable, rare and difficult to imitate will not actually deliver advantage if the firm lacks the organisation to capture its value (Barney, 1995). This criterion examines whether the company’s management systems, processes and structure are in place to fully exploit the resource’s potential. The firm must be ready and able to leverage the resource effectively. If not, that resource could remain underutilised or mismanaged – essentially a missed opportunity.

A well-known example is Amazon’s logistics network. Amazon’s extensive warehousing and distribution infrastructure is a valuable, rare and hard-to-imitate asset. However, what truly sets Amazon apart is how well the company has aligned its organisation to utilise this resource. Its algorithms, fulfilment processes and customer service systems are configured to fully leverage those resources, ensuring fast delivery and superior customer satisfaction at scale. In other words, Amazon finely tunes its fulfilment operations to capitalise on the strengths of this logistics network (Santini, 2024).

On the other hand, a company might have a great patented technology (valuable, rare, inimitable) but fail to commercialise it due to poor management or lack of strategic focus. Such a resource would not yield advantage until the organisation addresses those issues. Therefore, the “O” in VRIO reminds strategists that internal alignment is critical. Only when a firm is properly organised to harness a resource can the resource truly contribute to sustained competitive advantage.

Step-by-step VRIO analysis:

Step 1: Identify key resources and capabilities

Begin by making a broad list of the firm’s tangible and intangible resources. It’s often helpful to review the company’s value chain and its SWOT analysis to spot internal strengths (Jurevicius, 2025).

- Tangible assets might include proprietary technology, natural resources, facilities, or location advantages.

- Intangible resources include brand reputation, intellectual property (patents, trademarks), technical know-how, organisational culture, unique partnerships or skilled human capital.

Focus on the resources and capabilities that are strategically relevant – those that enable key business processes or underpin the firm’s strategy. For example, a firm’s highly efficient supply chain system, a team of expert engineers, or an exclusive distribution agreement could all be notable internal resources.

Step 2: Evaluate each resource against VRIO

For each resource or capability identified, ask the four VRIO questions methodically:

- Value: Does this resource contribute significant value? Does it help exploit an opportunity or mitigate a threat? (If not, it may be a candidate for divestment or improvement.)

- Rarity: How many competitors (if any) possess this same resource or capability? Is it scarce or widely available in the industry?

- Imitability: Would it be difficult for another firm to obtain or duplicate this resource? Consider the time, cost or complexity it would take for competitors to imitate it or find a substitute.

- Organisation: Is the firm organised, ready and able to effectively utilise this resource? Are there appropriate systems, processes and a supportive culture in place to fully exploit it?

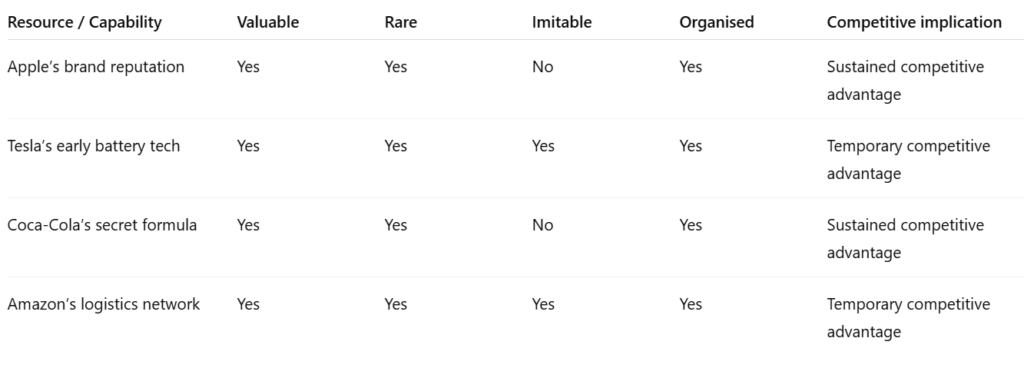

It can be useful to summarise the evaluation in a VRIO table for clarity. Each resource can be marked as “Yes” or “No” on the four criteria. For example, one resource might be Valuable (Yes), Rare (Yes) but Imitable (No) and properly Organised (Yes). Another might be valuable but not rare, and so on.

This exercise often reveals that only a subset of resources get “Yes” for most criteria, while many resources fail one or more tests.

Download a free VRIO analysis template and example (MS Word)

Step 3: Map results to competitive advantage

Finally, determine what each resource’s VRIO status implies for the firm’s competitive position:

If a resource fails the Value criterion (i.e. it’s not adding value), the firm faces a competitive disadvantage in that area. Such resources may be causing inefficiency or cost with no benefit. Management should consider improving, eliminating or replacing these.

If a resource is valuable but not rare (many rivals have something similar), it provides competitive parity at best. It’s essentially a necessary strength just to keep up with industry standards. The firm should maintain these resources (they are often “qualifiers” to compete) but not expect them to deliver unique profits.

If a resource is valuable and rare, but easily imitated or substitutable, it offers a temporary competitive advantage. The firm can enjoy some short-term differentiation, but rivals can likely catch up. For instance, a new product feature that competitors could copy within a year gives only a brief edge. In such cases, the firm should work to lengthen the advantage. For example, it could seek patent protection or continuously innovate so that by the time competitors catch up, the firm is already onto the next improvement (thus staying ahead).

If a resource is valuable, rare and inimitable, but the firm is not organised to exploit it, then the advantage is unused or latent. The firm possesses a potentially powerful asset but isn’t reaping the benefits due to internal shortcomings. This is a critical insight – it suggests the firm should change its organisation or strategy to unlock the resource’s value.

For example, a company might have highly talented employees (a valuable, rare, hard-to-imitate talent pool) but, if bureaucracy stifles their ideas, the company fails to benefit. Addressing such organisational gaps (e.g. by empowering employees or streamlining processes) can turn an unused advantage into a real one.

If a resource meets all four VRIO criteria – valuable, rare, inimitable and supported by organisation – it provides a sustained competitive advantage. The firm can expect this resource to be a long-term strength that competitors will find very hard to erode. These are the “crown jewels” of the company’s resource portfolio and should form the core of its strategy. For instance, a firm with a strong patented technology base and an excellent team and processes to exploit it will likely enjoy superior performance as long as those conditions hold (Barney, 1991).

By mapping each resource into these categories, managers (and students analysing a case) can prioritise strategic actions.

The VRIO analysis highlights which resources to build strategy around, which ones to protect or enhance, and where the firm has gaps. It is often useful to depict the outcome in a table or diagram to communicate the findings in a strategic report. For example, resources can be listed with checkmarks under V, R, I, O columns and an outcome like “Parity” or “Temporary advantage” for each. This visual summary gives a quick overview of where the firm’s competitive advantages lie.

Application of VRIO in assignments

VRIO analysis is commonly used in case studies, strategic reports and MBA projects to assess a company’s internal strengths. To effectively apply VRIO in an academic assignment, it’s important to integrate it into the overall strategic analysis rather than treat it as an isolated checklist. Below are some guidelines for using VRIO in coursework or case-study reports:

Introduce VRIO and its role

Begin by explaining what the VRIO framework is and why it matters for the case. For example, in a case study introduction you might write:

“This report uses a VRIO analysis to evaluate Company X’s internal resources in order to determine which of its strengths can yield a sustained competitive advantage.”

This statement sets the context and shows the reader that a structured internal analysis is being conducted. It adds credibility to your report and signals that you will assess the firm’s resources methodically.

Identify and justify key resources

Don’t try to analyse every single asset – focus on a few (usually 3–6) major resources or capabilities that are most relevant to the firm’s success. Clearly identify each chosen resource and justify why it’s important. Avoid listing generic items like “employees” or “technology” without context.

For instance, don’t just write “skilled employees” as a resource – specify what makes the employees a strategic asset (e.g. “a team of PhD researchers in AI driving product innovation”).

Similarly, rather than saying “technology”, you might highlight “a proprietary data analytics platform that competitors lack.” Providing this specificity shows you understand which aspects of the firm are truly valuable or unique. It also sets the stage for evaluating them with VRIO criteria.

Apply the VRIO criteria systematically

Structure the body of your analysis by assessing each key resource against the four VRIO criteria. A clear approach is to dedicate a paragraph (or a subsection) to each resource and discuss V, R, I, O in turn. For example, you could write:

“Resource A: Brand Reputation. This is valuable because it significantly influences customer choice and allows premium pricing. It is rare, as few competitors have such a trusted brand. Moreover, it’s difficult to imitate due to years of marketing and customer experience that rivals cannot easily replicate. The company is also well-organised to leverage its brand through consistent advertising, customer service and a culture of quality.”

By doing this for each resource, you demonstrate how the VRIO criteria translate to the specifics of the case. The analysis becomes structured and easy to follow.

Remember to link each point back to the company’s performance: if a resource meets the criteria, explain what kind of advantage it gives, and if it fails somewhere, note the limitation. This way, the reader can clearly see the implications of your VRIO findings.

Discuss implications for competitive advantage

After evaluating each resource, explicitly state what the VRIO result means for the company’s competitive position. Does this resource give the firm a sustained advantage, a temporary edge, parity with rivals, or is it a weakness? Integrate this into your case discussion.

For example, you might conclude:

“Our VRIO analysis indicates that Company X’s patented technology (Resource A) is a sustained competitive advantage and a cornerstone of its strategy. In contrast, its IT infrastructure (Resource B), although valuable, is common across the industry and thus provides only competitive parity.”

Such commentary connects the VRIO evaluation back to the bigger strategic picture. It shows the reader that you understand the so what of the analysis – how these internal factors affect the firm’s competitive standing. This also creates a nice bridge to the next part of your assignment (often the recommendations or strategy section).

Link VRIO analysis to recommendations

In many assignments, you will provide strategic recommendations after the analysis. Use the insights from the VRIO analysis to inform those recommendations.

For instance,

- If VRIO revealed an unused advantage (a valuable, rare, inimitable resource that the company isn’t fully exploiting due to poor organisation), one recommendation could be to restructure or invest in capabilities to better utilise that resource.

- If you identified a temporary advantage, you might recommend actions to extend or reinforce it – such as securing legal protection (patents, trademarks) or building complementary assets to make imitation harder.

- Similarly, if the analysis showed the company lacks any VRIO-qualified strength (no resource currently gives a sustained advantage), you might suggest developing or acquiring a distinctive capability as a strategic priority.

By tying recommendations to VRIO findings, you ensure your proposals are grounded in your analysis. This makes your strategy suggestions more convincing. It also demonstrates a higher level of insight: you’re not just analysing for its own sake, but using analysis to drive action.

Overall, applying VRIO in assignments is about clarity and relevance. Introduce the framework, focus on the key resources, evaluate them rigorously, and then use those findings to guide your strategic thinking. This integrated approach will typically earn higher marks than a stand-alone VRIO table with no connection to the rest of your case study.

Tips for leveraging VRIO findings

A VRIO analysis should lead to actionable insights. Here are some tips on translating VRIO findings into strategy and recommendations:

Protect and exploit rare resources

If your analysis identifies a resource that is both valuable and rare, ensure the company continues to own, protect and fully exploit it.

For example, if a particular technology or process gives an edge, the firm should safeguard it through patents or trade secrets (to prevent imitation).

The company should also invest in that resource to keep it strong – for instance, by continuing R&D on a cutting-edge technology or maintaining the quality and reputation of a valuable brand.

The goal is to prolong the resource’s value and rarity. Many firms put defensive “moats” around such advantages: Coca-Cola, for instance, famously guards its secret formula, and companies like Apple invest heavily in brand marketing and product innovation to stay ahead of imitators.

Lengthen temporary advantages

For resources that are valuable and rare but at risk of being imitated, consider steps to make the advantage last longer.

This could mean increasing complexity or uniqueness so that copying is more difficult. It may also involve creating complementary assets around the resource or leveraging lead-time advantages.

For instance, a software firm with an innovative feature (a temporary advantage) could release frequent updates and build a loyal user community. By the time competitors catch up, the firm is already onto the next innovation and has locked in customer loyalty.

The principle here is to extend the window of advantage. If you know an edge is temporary, plan how to reinforce it or follow it up with the next development.

Align organisation with key resources

Sometimes VRIO analysis shows that a company’s structure or systems are not fully aligned with its valuable resources. In such cases, the company should adjust internally to capitalise on what it has.

For example, if a firm’s R&D department produces great innovations but the bureaucratic culture slows down commercialisation, management might introduce more agile processes or a supportive innovation culture.

The idea is to remove internal obstacles. Ensure that the company configures its strategy, structure and systems to make the most of its resources.

In practice, this could mean reorganising teams, changing incentive schemes, improving knowledge sharing, or training staff – whatever helps the organisation exploit its strengths more effectively. In recommendations, this might be phrased as “invest in organisational capacity” or “realign structure to leverage X capability.”

Invest in filling resource gaps

VRIO can also highlight what the firm doesn’t have. If the analysis finds that none of the current resources confer a sustained advantage, or if it reveals a particular weakness, the company should consider developing or acquiring resources to fill those gaps.

For example, if all valuable resources are also commonly held by rivals (competitive parity), the firm might decide it needs a new distinctive capability to stand out. Alternatively, if a competitor has a critical resource that your firm lacks, you might invest in building a similar capability or finding a substitute.

In a strategic plan, this could translate into initiatives like “develop in-house data analytics expertise” or “acquire Company Y to gain their patented technology.” The key is that VRIO doesn’t just identify existing advantages – it also can direct a firm’s resource investment priorities.

Re-evaluate regularly

A firm’s internal environment is not static. The value and rarity of resources can change as industries evolve. What was rare can become common over time, and what was valuable can become obsolete with technological shifts. Therefore, treat VRIO analysis as a dynamic tool. It’s wise for companies to periodically revisit their VRIO assessment – for instance, annually or whenever there’s a major market change.

In strategic planning meetings, discuss which resources are emerging as new advantages and which might be losing their edge. This ensures the company can adjust its strategy, either by doubling down on new strengths or by addressing areas where a once-great resource is no longer special.

For students writing about this, you can note in your conclusion that “VRIO is not a one-off analysis; firms should continually re-assess their resources as conditions change.” This highlights the forward-looking application of VRIO.

Common mistakes to avoid

When conducting a VRIO analysis – whether in a professional context or for a class assignment – be mindful to avoid these common pitfalls:

Being too generic with resources:

One frequent error is listing broad, generic assets without specificity – for example, simply stating “our employees” or “modern technology” as a resource. This provides little insight.

VRIO analysis requires explaining what about those employees or that technology is valuable or rare. If every company has employees and computers, those aren’t inherently advantages. Instead, focus on specifics: e.g. a team of employees with unique expertise in biotechnology, or a proprietary AI software system the firm developed.

Always describe the resource in a way that shows its distinctiveness or strategic relevance.

A related mistake is failing to justify the VRIO criteria for each resource. It’s not enough to claim a resource is valuable or rare – you should provide a reason or evidence. For instance, instead of saying “Brand X is rare”, clarify why: perhaps Brand X has customer loyalty scores or market recognition that few rivals achieve.

Confusing internal and external factors:

Some students mix up VRIO with external analysis tools (like SWOT or PESTLE), treating it as if it covered external opportunities or threats. This is a mistake. Remember that VRIO focuses on a company’s internal capabilities, while tools like PESTLE or the external half of SWOT cover external factors.

For example, market trends or regulatory changes are not evaluated in VRIO – those belong in external analysis. In a VRIO section, stick to resources the firm possesses or controls. Keeping that clear boundary will strengthen your analysis and avoid confusion between internal and external drivers of strategy.

Ignoring the link to competitive advantage:

Conducting a VRIO analysis in a vacuum, without connecting it to the firm’s competitive outcome, is a missed opportunity. The whole point of VRIO is to determine if a resource leads to an advantage, so you should always tie your findings back to competitive impact.

Avoid simply listing resources with VRIO labels and then moving on. Instead, for each resource, conclude with what it implies: e.g. “thus this capability provides only a temporary advantage until competitors catch up,” or “this resource is a sustained advantage that has fueled the company’s superior profits.”

By doing this, you demonstrate that you understand the strategic significance of the VRIO analysis. It makes your report more insightful and cohesive.

Overlooking the ‘Organisation’ aspect:

Many analyses focus on Value, Rarity and Imitability, but give scant attention to whether the firm is actually organised to use the resource effectively. This is a significant oversight because organisation can be the deciding factor between having a resource in theory and benefiting from it in practice. Therefore, always discuss whether the company is organised to capitalise on its strengths.

For example, Singapore Airlines has valuable service quality and a strong brand, but it is the airline’s training programmes, customer-centric culture and operational excellence that ensure this advantage is fully utilised. In your analysis, if you identify a great resource, double-check that you’ve also considered the firm’s ability to deploy it. If you find that lacking, note it as an issue to address.

Lack of evidence or examples:

As with any business analysis, VRIO arguments are stronger when backed by evidence or examples. A common mistake is making assertions like “our supply chain is inimitable” without support. Instead, try to include a supporting fact – for example, “the supply chain is inimitable because it is built on a patented tracking system and a decade of proprietary data.”

In academic work, referencing case facts or data (or even citing research) can substantiate why you judged a resource as meeting or failing a criterion. This not only strengthens your analysis but also shows a critical, evidence-based mindset. It demonstrates to the reader or examiner that your VRIO evaluation is not just opinion, but grounded in factual observation.

Analysing too many resources:

Finally, attempting to evaluate a long list of resources can make your analysis shallow and unfocused. It’s usually more effective to concentrate on the most material resources that truly drive competitive advantage. Prioritise quality over quantity. If you list everything from office furniture to corporate culture, you’ll dilute the analysis. Focus on the 3–5 key resources that differentiate the firm. This keeps your VRIO discussion tight and meaningful. In an assignment, it also helps you stay within word limits and maintain a clear narrative.

Struggling with a VRIO analysis or another management assignment? Our MBA-qualified management writers can create a bespoke model answer, tailored to your brief and written to the grade you order. Get the guidance you need – see our management assignment help page.

References and further reading:

- Barney, J. B. (1991) ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’, Journal of Management, 17(1), pp. 99–120.

- Barney, J. B. (1995) ‘Looking inside for competitive advantage’, Academy of Management Executive, 9(4), pp. 49–61.

- Brand Finance (2025) Global 500 Rankings 2022 – World’s most valuable brands. Available at: https://static.brandirectory.com/reports/brand-finance-global-500-2025-preview.pdf (Accessed: 10 September 2025).

- Jurevicius, O. (2025) ‘VRIO Framework Explained’, Strategic Management Insight. Available at: https://strategicmanagementinsight.com (Accessed: 9 September 2025).

- Santini, S. (2024) ‘Understanding the VRIO framework: A strategic tool for competitive advantage’, Herdr Blog, 21 November 2024. Available at: https://blog.herdr.io (Accessed: 9 September 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: