Blue ocean strategy guide

Info: 7255 words (29 pages) Study Guides

Published: 01 Oct 2025

Need help with a management assignment? Our professional writing service can provide tailored support with essays, reports and case studies at any level. See our management assignment help page for more info.

Business history is replete with companies fiercely battling each other for market share in crowded industries. This scenario is what Blue Ocean Strategy terms a “red ocean” – a bloodied sea of rivals fighting over shrinking profits.

By contrast, a blue ocean denotes an untapped market space with the potential for high growth and profitability, where competition is rendered irrelevant. Blue Ocean Strategy (BOS) is a strategic framework developed by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne that focuses on creating such uncontested markets instead of competing head-to-head with other firms. It offers a systematic approach to make the competition irrelevant by redefining industry boundaries and delivering new value to customers.

Blue Ocean Strategy has gained prominence among academics and practitioners alike because it promises significant performance gains. In a landmark study of 108 companies, Kim and Mauborgne (2004) found that only 14% of new business launches created blue oceans (new markets), yet these moves generated 38% of total revenues and 61% of total profits.

In contrast, 86% of launches were incremental “red ocean” extensions that delivered the majority of revenue but only 39% of total profit.

This striking imbalance underlines why strategists are increasingly interested in looking beyond traditional competition. Indeed, companies that successfully pioneer blue oceans often reap the benefits for a decade or more without serious challenges, as competitors either fail to catch up or choose not to imitate due to high barriers.

What is Blue Ocean Strategy?

Blue Ocean Strategy is the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost to open up a new market space and create new demand. In essence, it is about creating and capturing uncontested market space, thereby making the competition irrelevant.

This concept was introduced by Kim and Mauborgne in the early 2000s and popularised in their 2005 book Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant. The term draws a vivid contrast with “red oceans,” which represent the known market space of existing industries where firms engage in cut-throat competition.

In a red ocean, industry boundaries are defined and accepted, and companies try to outperform rivals to grab a larger share of existing demand. As more players crowd into the market, prospects for growth and profit shrink – products become commodities and competition turns the water red with blood.

By contrast, blue oceans symbolise the unknown market space – industries or segments not in existence or significantly untapped. Demand in blue oceans is to be created rather than fought over, and the opportunity for profitable growth is vast and rapid.

Instead of taking industry conditions as given, Blue Ocean Strategy is built on the idea that market boundaries and rules can be reconstructed by entrepreneurial insight and strategic creativity. It represents a shift from a structuralist view (where structure shapes strategy) to a reconstructionist view (where strategy can reshape industry structure). In practical terms, BOS pushes firms to think differently – to ask not “How can we beat the competition?” but “How can we make the competition irrelevant by offering a leap in value to buyers and by cutting costs?”

Crucially, Blue Ocean Strategy rejects the traditional value-cost trade-off. In classic strategy thinking influenced by Michael Porter, firms choose either a differentiation strategy (offering superior value at higher cost) or a low-cost strategy (offering basic value at lower cost).

Kim and Mauborgne (2005) argue that this is a false dichotomy. Instead, they advocate achieving differentiation and low cost simultaneously through what they call value innovation.

Value innovation is the cornerstone of BOS – it means innovating in a way that creates value for both the customer and the company, breaking the trade-off between value and cost. By innovating on the utility side (what buyers value) while also innovating to eliminate or reduce costly features, a company can offer a product or service that is qualitatively superior and cheaper to produce. This creates a win-win: buyers get an unprecedented leap in value, and the company achieves lower costs and can potentially reach new customers.

For example: The French company Groupe SEB created the ActiFry deep fryer that used only a small spoonful of oil, delivering healthier fried food. It provided a unique value (healthy frying) and reduced costs (less oil, simpler design) – a value innovation that opened a new market of health-conscious consumers (example adapted from Kim & Mauborgne, 2017).

Notably, Blue Ocean Strategy is grounded in extensive research. The framework emerged from a decade-long study of more than 150 strategic moves across over 30 industries and 100 years. These studies ranged from circus entertainment and wine to automobiles and IT, and they revealed patterns in how industries were created and transformed.

The recurring theme was that major long-term success came not from competing within established markets, but from creating new markets – whether by inventing entirely new industries or reshaping existing ones.

Blue ocean creators often look very different from their competitors, and their strategic moves are the unit of analysis in BOS. Instead of focusing on why some companies outperform others in the same industry, BOS examines the strategic move – the set of managerial actions and decisions that create a significant new market. This perspective helps isolate what companies do to unlock new demand and high growth.

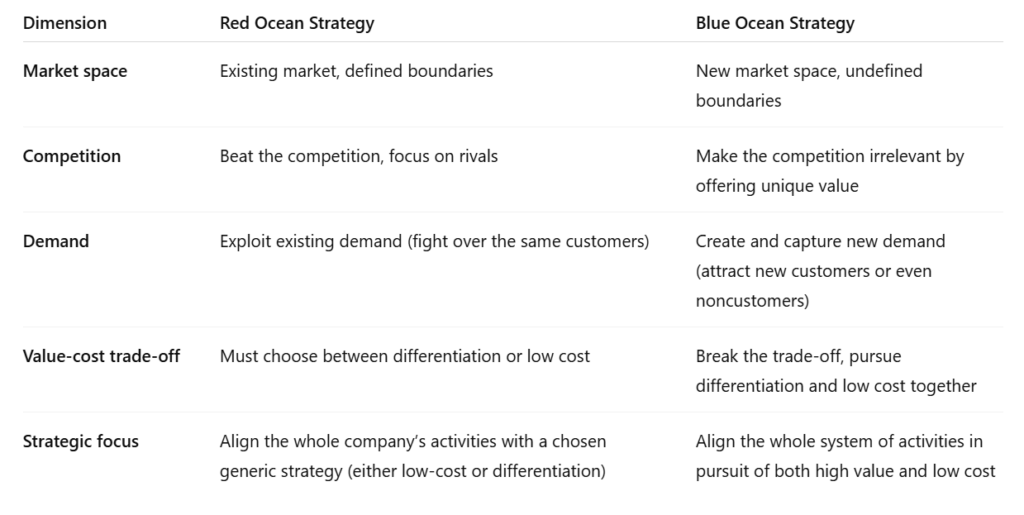

Red oceans vs. blue oceans

To fully grasp BOS, it is important to compare red oceans and blue oceans directly. Red oceans represent all existing industries and market spaces. In red oceans, companies accept the prevailing boundaries of their industry and the competitive rules of the game.

Strategy in red oceans is largely about outperforming rivals – capturing a bigger slice of existing demand, often at others’ expense. As competition intensifies, any advantage is typically temporary and the market may become saturated, leading to reduced growth prospects.

Industries in red oceans often see products converging towards commoditisation, price wars eroding margins, and a general squeeze on profitability. In other words, a red ocean strategy is a zero-sum game: one firm’s gain is another’s loss, and the “ocean” turns bloody as rivals cut each other down.

By contrast, blue oceans denote those market spaces that are new, uncontested, or unknown. Here, competition is absent (at least initially) because the space is unclaimed – the rules are not set yet.

Rather than competing over a fixed pie, companies in blue oceans create a new pie or expand the existing one, attracting customers who were not previously served. In blue oceans, demand is created instead of fought over, and growth can be both rapid and profitable because the firm faces little or no rivalry. A blue ocean is analogous to a wide, deep ocean that firms can freely sail in, with ample opportunity.

The table below summarises the key differences between red ocean and blue ocean strategy:

It is worth noting that blue oceans can be created within red oceans. Often, a blue ocean is born when a company redefines the boundaries of an existing industry, rather than by pure technological invention.

For example: Cirque du Soleil created a blue ocean within the circus and live entertainment industry by blending elements of circus with theatre and abstract storytelling. It did not invent “circus” or “theatre” anew, but by reconstructing these offerings and eliminating conventional circus elements (like animals and star clowns) while adding new elements, it unlocked a new market of adult theatre-goers willing to pay a premium for a novel experience.

In general, blue oceans can emerge from within red oceans when a firm fundamentally changes the factors of competition and the audience, thereby creating a new subspace where it has the waters to itself.

Core principles and tools of Blue Ocean Strategy

Blue Ocean Strategy provides a set of principles and analytical tools to help managers systematically pursue new market spaces. The goal is to move away from head-to-head competition and instead reconstruct buyer value elements to craft an offering that is both distinctive and low-cost. Below, we outline some of the core principles and frameworks of BOS:

Value innovation and the value-cost trade-off

At the heart of BOS is value innovation – achieving a leap in value for both customers and the company. Value innovation occurs when a company’s actions positively affect both its cost structure and the value proposition to buyers.

On the cost side, costs are driven down by eliminating or reducing factors an industry competes on. On the buyer side, value is lifted by raising existing factors and creating new ones that the industry has not offered before. Through this simultaneous pursuit, the firm breaks the value-cost trade-off: it is not offering more value at higher cost, nor low value at lower cost, but more value at lower cost. This defies conventional strategic logic and requires a different mindset.

For example: Southwest Airlines is often cited as a case of value innovation in its early years. Traditional airlines competed on meals, seat classes, lounges, and assigned seating – all of which raised costs – while also trying to offer speed. Southwest eliminated meals and frills, used a single class of seating and secondary airports (reducing cost), but raised the value in areas customers cared about: fast point-to-point travel, frequent departures, and friendly service. The result was a new kind of air travel that was both low-cost and appealing to a broad range of travellers, including those who previously would have taken buses or cars. By not engaging in the same trade-offs as rivals, Southwest unlocked huge new demand and enjoyed years of profitable growth in a “blue ocean” of its own making.

The principle here is that strategy should not be a zero-sum choice between differentiation and cost leadership. Instead, through value innovation, a firm seeks what Kim and Mauborgne call a “leap in value” – an offering that is so superior on key dimensions of buyer value and yet lower cost to deliver that it makes the old offerings obsolete. This is how the competition is made irrelevant: customers flock to the new value, and competitors, even if they try to imitate, find themselves unable to match the innovator’s cost structure or value appeal without fundamental changes to their own business models.

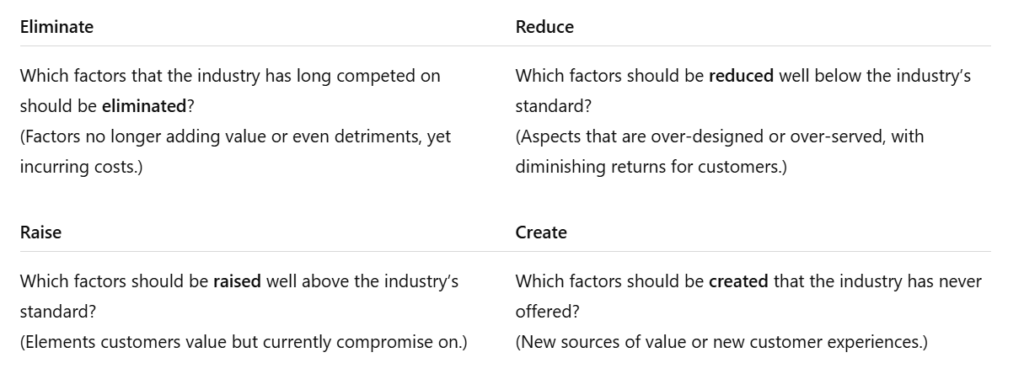

The Four Actions Framework (Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create)

To systematically pursue value innovation, Kim and Mauborgne propose the Four Actions Framework, which prompts firms to rethink how they are competing. Managers are asked to consider four key questions about the factors their industry competes on:

- Eliminate – Which factors that the industry has long competed on should be eliminated? (These may be factors that no longer add value to customers or are even detriments, yet incur cost.)

- Reduce – Which factors should be reduced well below the industry’s standard? (Here one targets aspects that are over-designed or over-served, providing diminishing returns for customers.)

- Raise – Which factors should be raised well above the industry’s standard? (Identify aspects that are under-served – elements customers value but currently compromise on – and enhance them.)

- Create – Which factors should be created that the industry has never offered? (This encourages thinking about entirely new sources of value or new experiences to offer to customers.)

By using these four actions, a company can construct a new value curve that diverges sharply from other players in the industry.

This approach results in what’s known as an ERRC grid (Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create grid), which is a practical tool for brainstorming changes to the status quo.

The ERRC grid pushes companies to question everything they take for granted in their industry and to not just make incremental improvements, but to step outside of current paradigms.

For example: When Nintendo applied this framework in the mid-2000s for the Nintendo Wii console, they eliminated or reduced factors like cutting-edge graphics, complex controllers, and expensive hardware (features that core gamers prized but that added cost and alienated non-gamers). Simultaneously, Nintendo raised user-friendliness and created an intuitive motion-control gaming experience with family-friendly games, which had never been a focus of the video game industry. The result was a revolutionary console that appealed to noncustomers (people who had never played video games before) and sold over 100 million units worldwide, outpacing rivals. The Wii’s ERRC changes broke the traditional value-cost equation: it delivered a fun, accessible gaming experience (high buyer value) at a fraction of the development cost of high-end consoles.

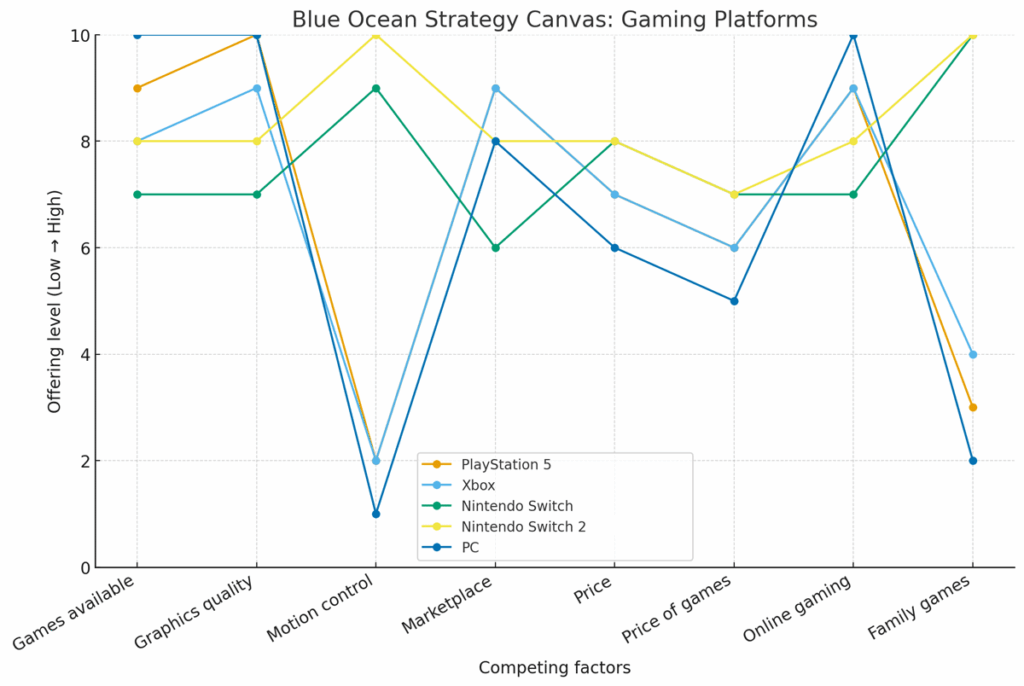

Strategy canvas and value curve

A central diagnostic and planning tool of BOS is the strategy canvas. The strategy canvas is a one-page graphical representation that plots the current and potential factors of competition on the horizontal axis and the offering level that customers receive on the vertical axis. Each industry or player will have a “value curve” on this canvas – essentially a line graph connecting the offering levels across the competing factors.

The strategy canvas serves two purposes:

- It captures the current state of play in the known market (the red ocean) – showing how competitors invest in and deliver value on each factor.

- It highlights where a new entrant or an innovator might diverge from the existing competition by offering a different mix of factors.

A good blue ocean strategy is visually apparent on a strategy canvas: the value curve of the blue ocean move is distinct from the incumbent players’. Kim and Mauborgne note that effective blue ocean strategies tend to exhibit three qualities: focus, divergence, and a compelling tagline.

Focus means the company does not diffuse its effort across every possible factor of competition, but focuses on the key factors that really matter to its new value proposition. Divergence means the value curve deviates significantly from those of competitors – the shape is different because the strategy is not benchmarking rivals, but creating a new offering. And a compelling tagline means the strategic profile can be summed up in a clear, truthful phrase that speaks to customers.

Example: The Australian wine [yellow tail]’s strategy can be summarizsd as “a fun and simple wine to be enjoyed every day” (Blue Ocean Team, n.d.). [yellow tail]’s strategy canvas diverged from other wines by eliminating or reducing complexity and pretension (it offered just two varietals with easy taste, scrapped technical jargon and aging qualities), and by creating a casual, approachable image akin to beer or cocktails. Its value curve showed focus (only a few key factors like price, easy drinking taste, and retail friendliness) and divergence (it did not compete on prestige, oenological pedigree, or variety breadth as other wines did). The compelling tagline captured its essence and helped employees and customers alike understand its unique value. Such clarity is vital; a fuzzy or overly complex strategy is hard to execute.

In practice, managers can draw a strategy canvas for their industry, plot the value curves of major competitors, and then sketch how their own strategy might look if they eliminate some factors, reduce others, raise some, and create new ones. This visual approach (sometimes called “visual strategy”) is powerful for communicating the new strategy internally and ensuring there is alignment around the new value proposition. An effective value curve should clearly show a departure from the competition’s pattern and embody a distinctive vision for the offering.

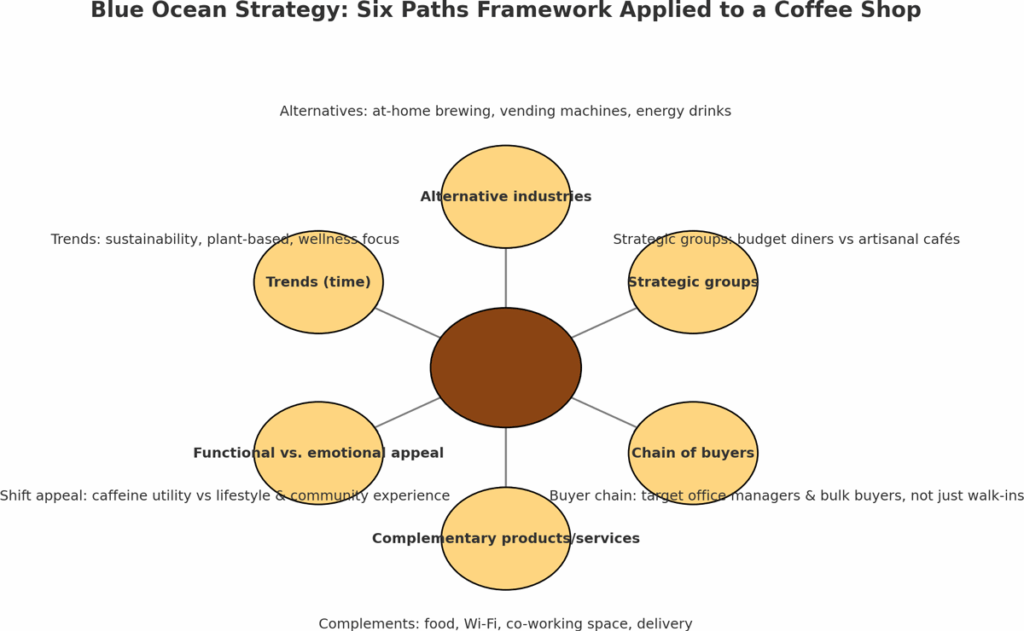

Six paths framework and looking beyond existing demand

Another BOS principle is to systematically reconstruct market boundaries by looking across conventional boundaries that limit imagination. Kim and Mauborgne (2005) outline six basic paths that companies can explore to discover blue oceans:

Look across alternative industries –

Consider substitutes or alternatives to your product that consumers use. Companies often compete within one industry, but customers weigh alternatives (for example, cinemas vs. home streaming, or restaurants vs. cooking at home). A blue ocean can be found by offering the best of two alternatives or by creating a new alternative that addresses the shortcomings of each.

Look across strategic groups within industries –

Most industries have high-end and low-end segments (strategic groups) defined by price and performance. Shifting the line between these groups or serving unmet needs of a segment can open new space. (For instance, Toyota’s launch of the Lexus brand injected luxury features at a more accessible price, capturing customers between traditional luxury and mass-market cars.)

Look across the chain of buyers –

Identify the different roles in the purchase decision (end-users, purchasers, influencers). While an industry usually targets a defined buyer (e.g., pharmaceutical companies target doctors as prescribers rather than patients), shifting focus to a different buyer group can unlock new value. (Canon, for example, sold small copiers to office workers (end-users) directly, whereas its rival Xerox sold to central corporate purchasing – Canon’s different focus created a new market for personal copiers.)

Look across complementary products and services –

Consider the context in which your product is used. What happens before, during, and after its use? Removing hassles or adding complementary value can create new demand. (Apple’s iTunes, for example, complemented the iPod by making legal music purchase simple – this convenience significantly boosted iPod’s appeal.)

Look across functional and emotional appeal to buyers –

Industries usually compete either on functional, practical appeal or on emotional appeal. Shifting the orientation can open new markets. (Swatch, for instance, transformed watches – which had become functionally similar timekeepers – into fashion accessories by using bold designs and marketing fun, emotional value at a low price. This move attracted consumers who didn’t wear watches for utility but as style statements.)

Look across time (trends) –

Identify trends that will shape future consumer behaviour, and act on them with a value innovation. The idea is not to predict uncertain futures, but to spot a clear trajectory (like the wellness trend, or environmental sustainability) and pioneer offerings that position you ahead of this curve.

These six paths encourage thinking beyond the usual confines. Rather than defining one’s business too narrowly (the classic marketing myopia problem), managers can explore broader value opportunities.

Often, the trick is to find noncustomers – people who are not buying from your industry – and understand how to draw them in. BOS speaks of three tiers of noncustomers.

- First-tier noncustomers are on the edge of your market (occasional or soon-to-be ex-customers);

- second-tier are people who consciously refuse current offerings; and

- third-tier are those who have never been targeted or interested.

By examining why these noncustomers exist and what they might value, a firm can uncover insights for new demand.

For example: Cirque du Soleil won over adults and corporate clients who normally did not attend circuses (they preferred theatre or opera). It did so by offering sophistication, narrative and aesthetic richness more akin to theatre, while stripping away circus elements that alienated those customers (no animals, no cheesy clowns). In doing so, Cirque tapped into a huge pool of noncustomers and got them to happily pay several times the price of a normal circus ticket for an unprecedented experience (Kim & Mauborgne, 2004).

Execution and fair process

Formulating a blue ocean strategy is only part of the challenge; effective execution is also crucial. BOS emphasises building execution into strategy from the start.

Because blue ocean moves often involve significant change – upending the status quo, reallocating resources, and even shifting mindsets – organisations can face internal hurdles. The authors identify typical hurdles: cognitive (employees struggling to understand the need for change), resource (reallocating budgets and personnel), motivational (keeping people committed), and political (overcoming opposition from vested interests).

One approach advocated is Tipping Point Leadership, which involves concentrating resources on key leverage points that overcome those hurdles quickly (e.g., mobilising a few influential people rather than trying to convince everyone at once).

Another is the concept of fair process – treating people fairly in the strategy-making process by engaging them, explaining decisions, and setting clear expectations. When employees feel they have been heard and the process is just, they are far more likely to execute a new strategy even if it’s disruptive to their routines.

Blue Ocean Strategy literature often stresses that a brilliant strategy will falter if the people expected to carry it out are not on board. Therefore, in BOS workshops and in the Blue Ocean Shift methodology, there is a heavy focus on team participation, visual communication tools that everyone can grasp, and steps that build people’s confidence in the new direction.

Finally, Blue Ocean Strategy underscores aligning three propositions:

- the value proposition (for buyers),

- the profit proposition (for the firm), and

- the people proposition (for employees and partners).

A strategy will only succeed if it creates compelling value for customers, keeps the company profitable (via an appropriate cost structure and pricing), and motivates those who implement or support it. A win-win outcome is achieved when all three are in harmony.

In practice, this might mean ensuring that employees are not alienated by the changes (through retraining or incentives), that the new offering can be delivered at a cost that makes economic sense, and that customers truly perceive the new value as exceptional. By addressing these elements, BOS seeks to build humanness and sustainability into the strategy development process.

Developing a Blue Ocean Strategy: A step-by-step approach

While each business situation is unique, a general process for developing a blue ocean strategy can be outlined, drawing on Kim and Mauborgne’s recommendations (Kim & Mauborgne, 2017):

Assess the current state of play –

Begin with a clear understanding of the current market and the company’s situation. Use tools like the strategy canvas to map the existing competitive landscape. Identify the factors your industry competes on and how you and your rivals perform on each. This will highlight the prevailing strategic profiles and where competition is fiercest, helping you spot areas that are over-served or under-served. It sets the stage for seeing where opportunities might lie.

Imagine a new value curve –

Challenge the assumptions of your industry. Apply the Four Actions Framework (Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create) to brainstorm how you could deliver dramatically more value to customers and cut costs.

Ask the four questions systematically:

- What could we eliminate that is taken for granted?

- What could we reduce below the standard?

- What should we raise above the standard?

- What new factors could we create to delight customers?

At this ideation stage, think broadly and focus on customer pain points and unmet needs, including those of noncustomers. Encourage out-of-the-box thinking without immediately worrying about constraints.

Explore the six paths –

To ensure you’re not trapped in conventional thinking, examine your strategic options through the lens of the Six Paths Framework. Look for insights by stepping outside your traditional focus: consider –

- alternative industries,

- strategic groups,

- buyer chains,

- complementary offerings,

- the functional–emotional orientation, and

- impending trends.

This exploration often reveals non-obvious opportunities. For example, you might discover that your service could be bundled with an offering from another industry to create a new experience, or that a segment of customers currently served by an adjacent industry could be drawn into yours with a value innovation.

Focus on a big idea and finalise the new strategy canvas –

From the various ideas generated, identify the most promising strategic move – the one that could create a true blue ocean.

Use visualisation: draw a new strategy canvas for the proposed strategy against the current competition. Ensure that the new value curve has the three hallmarks (focus, divergence, compelling tagline) indicating a clear and bold strategy.

Also run the idea through a strategy sequence test to confirm it makes business sense:

- Does it offer exceptional buyer utility (will customers be excited to buy it)?

- Can you set a strategic price that’s attractive to the mass of target buyers?

- Can your cost structure support that price profitably (after eliminating/reducing factors and achieving scale)?

- Are there any adoption hurdles (e.g., distributor reluctance or customer habits) that need to be addressed?

Only if the idea passes these checks – utility, price, cost, adoption – is it a commercially viable blue ocean opportunity worth pursuing full-scale.

Test and refine through small moves –

Before a big bang launch, it can be wise to conduct rapid tests or pilots to validate critical assumptions. Blue ocean strategies carry uncertainty, so testing the waters can minimise downside risk. This might involve creating a prototype, running a focus group, or launching in a small market to gather feedback.

The goal is to learn quickly and refine the concept. For instance, if the new value proposition isn’t resonating as expected, you might tweak certain features or adjust the marketing message. Because BOS is iterative, this step ensures you don’t fully commit until the strategy is solid.

Launch boldly and execute –

Once refined, roll out the strategy and capture the new market. Execution should be swift enough to build momentum – being first to scale can establish brand dominance and customer loyalty, which are powerful defences.

At this stage, it’s crucial to communicate the new strategy throughout the organisation so that all departments (product development, operations, sales, customer service, etc.) align their activities to deliver the new value.

BOS advocates an inclusive and visual communication style, so every employee understands how the new strategy differs from the old and how their role contributes to it. Celebrate early wins and use them to reinforce buy-in.

Overcome organisational hurdles –

As the strategy is implemented, be prepared to deal with internal resistance or unforeseen challenges. Use tipping point leadership by concentrating efforts on key influence factors – for example, get a critical mass of support by converting key opinion leaders within the company.

Address resource hurdles by reallocating budgets from old areas that the new strategy renders less relevant (for instance, if you’re eliminating certain features, save costs there and channel resources to the new features).

Keep employees motivated by recognising their contributions and reiterating the exciting future this blue ocean can bring.

Politically, neutralise opposition by involving skeptics constructively or by making it clear that the status quo is not sustainable.

Throughout, apply fair process – communicate the whys behind strategic decisions and treat people with respect – so that even those who are personally affected by changes (like budget cuts in their department) understand the greater good and feel fairly treated. This fosters trust and cooperation rather than sabotage or foot-dragging.

Monitor and renew –

After a successful launch, continuously monitor the new market. A blue ocean will eventually attract imitators or new entrants if the profit opportunities are large. Recognise when the once-blue ocean is starting to turn red with competition. At that point, a company should not fall back into defensive competition, but rather look to create additional blue oceans. In other words, make market-creating innovation a repeatable process. This might involve launching follow-up innovations or even phasing out your own offering with a new one before competitors do. The concept of Blue Ocean Shift (Kim & Mauborgne, 2017) is about building an organisation that keeps moving to new blue oceans as old ones become commonplace. By institutionalising the BOS mindset – encouraging teams to regularly explore the six paths and revisit the strategy canvas – a company can stay ahead of the game.

Following these steps, even established companies can systematically innovate to find new profit frontiers. The process emphasises a blend of creativity and analytical rigour, as well as a strong focus on people (both customers and employees). BOS is as much about how you arrive at a strategy as the strategy itself – by engaging people and using visual tools, it seeks to unlock an organisation’s collective wisdom and willingness to venture beyond the horizon.

Real-world examples of Blue Ocean Strategy

Several high-profile business successes illustrate how Blue Ocean Strategy works in practice. Below, we examine a few classic and contemporary cases from different industries, highlighting how each applied BOS principles to create their own blue ocean.

Cirque du Soleil – reinventing the circus

One of the most emblematic examples of Blue Ocean Strategy is Cirque du Soleil. Founded in 1984 by a troupe of street performers in Canada, Cirque du Soleil achieved revenue levels in two decades that the traditional Ringling Bros. circus took over a century to attain. This success occurred even as the circus industry was widely considered to be in decline and unattractive – children were less interested in circuses, alternative entertainments like video games had grown, and there was rising public criticism of circuses over animal welfare.

Rather than competing head-on with incumbent circuses for a dwindling audience of children, Cirque du Soleil created a blue ocean by appealing to a new group of customers: adult theatre-goers and corporate clients willing to pay a premium for a sophisticated entertainment experienc.

Cirque’s strategy eliminated or radically changed many traditional circus elements. They eliminated costly features like animal acts (avoiding high animal care costs and appeasing ethical concerns) and the star clown or ringmaster focus.

They reduced the traditional circus’s emphasis on multiple rings and simultaneous acts – instead of sensory overload, Cirque offers a single, cohesive storyline and theme in each show, more akin to a play.

At the same time, Cirque raised certain factors: it introduced artistic themes, live original music, and theatrical storytelling, adding an emotional and intellectual depth never seen in a circus.

It also created elements drawn from Broadway and the opera: high-calibre acrobatics combined with dance, imaginative costumes, and stagecraft, all woven into an immersive narrative.

By fusing circus arts with the sophistication of theatre, Cirque du Soleil crafted a new form of entertainment – essentially a new genre that was neither conventional circus nor traditional stage theatre, but a blend of the most captivating aspects of both.

This delivered unprecedented value to adults and corporate spectators, who were prepared to pay several times the price of a traditional circus ticket for an “unprecedented entertainment experience”.

Internally, many of these innovations also lowered costs (e.g., no animals or expensive star performers), even as spending increased on areas like production design. Thus, Cirque achieved differentiation (a unique, high-quality artistic experience) and low cost simultaneously. It made the competition irrelevant – Ringling Bros. could not easily imitate Cirque’s concept without abandoning its own heritage and business model.

For years, Cirque du Soleil had this blue ocean largely to itself, expanding globally and launching multiple shows (each with a different theme) that attracted millions of spectators who typically had not been circus customers before. .

Nintendo Wii – gaming for the non-gamers

By the early 2000s, the video game industry appeared to be an intense red ocean dominated by two giants: Sony’s PlayStation and Microsoft’s Xbox. Both companies were locked in a technology arms race, producing ever more powerful consoles with high-end graphics, fast processors, and complex controllers to satisfy hardcore gamers.

In 2006, Nintendo – a veteran of the industry that had fallen behind in the graphics and power competition – chose a blue ocean strategy with the launch of the Nintendo Wii. Instead of trying to outdo Sony and Microsoft on technical specifications (which would have been extremely costly and would appeal only to the same hardcore demographic), Nintendo looked to the vast pool of non-gamers: people who typically did not play video games, including families with young children, women, and older adults.

Using the Four Actions Framework, Nintendo’s strategy with the Wii was clear.

It eliminated or drastically reduced several factors the rest of the industry took for granted: cutting-edge graphics, high-end processing power, DVD playback, and a plethora of buttons on the controller were deemphasised or left out. The Wii’s hardware was relatively simple and inexpensive compared to rival consoles.

Nintendo raised emphasis on approachability and social, physical engagement. Most notably, it created a new way to play: the motion-sensing Wii Remote controller, which allowed users to control games through natural movements (like swinging a tennis racket or golf club) rather than complex button combinations. This innovation made gaming instantly intuitive and fun for people who found traditional controllers intimidating.

Nintendo also created games that appealed to this new audience – e.g., Wii Sports, which was bundled with the console, offered easy-to-understand sports games that could be enjoyed by a group in a living room, and titles like Wii Fit introduced fitness gaming to attract health-conscious non-gamers.

The result was a huge new market space: retirement homes held bowling tournaments on Wii Sports, parents and grandparents played video games with their children, and even people who never considered themselves “gamers” bought a Wii for casual entertainment and exercise.

The Wii console opened up a new market by pulling in traditional noncustomers and ended up outselling both Sony’s PlayStation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360 by a wide margin during that console generation (Blue Ocean Team, n.d.). It was a huge success, becoming by 2008 the fastest-selling home video game system of all time in the US and many other markets. Importantly, the Wii was profitable from day one due to its low-cost design, unlike its competitors which initially sold hardware at a loss.

Sony and Microsoft were caught off-guard – their strategies and brand images were tied to top-tier performance and mature content, so they struggled to respond. By the time they introduced motion controllers or more casual games, Nintendo had already captured the blue ocean of casual and family gaming.

Although the Wii’s dominance waned later with the rise of smartphone gaming (an unforeseen disruption that pulled casual gamers to mobile) and Nintendo eventually had to seek another blue ocean with the Switch console, the Wii stands as a landmark example of BOS. It shows how focusing on nonusers and breaking industry assumptions (like “better graphics = better console”) can yield a quantum leap in demand.

[yellow tail] – making wine accessible to the masses

The wine industry in the late 1990s was intensely competitive and often intimidating to new consumers. Traditional wine marketing emphasised terroir, aging, and sophisticated taste distinctions – factors that appealed to connoisseurs but alienated many average alcohol drinkers.

Australia’s Casella Wines saw an opportunity to create a blue ocean by demystifying and simplifying wine for the broader market. In 2001, they launched [yellow tail], a wine brand aimed not at wine aficionados but at beer and cocktail drinkers – essentially, the mass of alcohol consumers who typically avoided wine.

Casella applied BOS by shifting the focus of competition in the US wine market. They eliminated or reduced many factors that wineries traditionally competed on. For example, [yellow tail] did away with the pretentious wine jargon on labels, the extensive aging process, and the huge palette of varietals and blends.

Initially, they offered only two choices: a Chardonnay (white) and a Shiraz (red), the most popular varietals in the US market. The taste profile of [yellow tail] was deliberately made sweeter and smoother than typical dry wines, to be immediately palatable to people without wine experience. Wine critics might have frowned on that, but Casella recognised that nonwine-drinkers found conventional wines too tannic or complex.

Simultaneously, they raised elements of fun and ease. The branding was bright and playful, featuring a kangaroo logo and vibrant colours, signaling that this wine was casual and not elitist. They also created a friendly in-store experience: they simplified choice (two main varietals, in approachable style), and they even encouraged retailers to merchandise [yellow tail] with eye-catching displays and offer it as a fun, entry-level wine. Store clerks were given Australian outback-themed clothing and encouraged to recommend [yellow tail] to unsure customers, turning them into brand ambassadors (Blue Ocean Team, n.d.).

The outcome was a wine whose strategic profile broke away from the competition. Instead of offering wine as a complex, acquired-taste luxury, Casella created “a social drink accessible to everyone”. [yellow tail] was a completely new mix of characteristics: an uncomplicated, easy-drinking wine that could be enjoyed without years of wine appreciation, sold in a simple format.

The industry’s experts criticised the sweetness and simplicity of [yellow tail], but consumers loved it. By eliminating and reducing what average drinkers didn’t value (complexity, aging, prestige markers) and adding what they did value (sweet fruitiness, fun branding, easy choice), [yellow tail] unlocked a huge untapped market.

In its first year, Casella had aimed to sell 25,000 cases in the US; they sold nine times that amount. By the end of 2005, cumulative sales reached 25 million cases, making [yellow tail] the #1 imported wine in the United States and the fastest-growing wine brand (Blue Ocean Team, n.d.). It soon became the best-selling 750ml red wine in the US, surpassing established Californian, French and Italian labels.

The strategy canvas of [yellow tail] (often shown in BOS materials) highlights how its value curve diverged from competitors. It focused on a few key factors: easy drinking taste, approachable branding, and convenience, rather than a broad spectrum of taste complexity, aging, and vineyard heritage.

[yellow tail] also had a clear tagline or strategic profile: “a fun and simple wine to be enjoyed every day”. This clarity of purpose resonated with employees, distributors, and customers alike. The [yellow tail] case demonstrates that innovation doesn’t always require new technology – sometimes it’s about reimagining how an existing product is presented and to whom.

Marvel – from bankrupt comics to a blockbuster universe

Blue Ocean Strategy is not limited to new products or small firms – it can also guide the dramatic transformation of large companies. A striking example is Marvel Entertainment.

In the late 1990s, Marvel (famous for comic book characters like Spider-Man and Iron Man) was in dire straits: the company had filed for bankruptcy in 1996, suffering from a collapse in comic book sales and a series of missteps by management that alienated both fans and talent.

By 2000, Marvel was a struggling company primarily licensing its characters to movie studios and toy makers for short-term cash. Yet, roughly a decade later, Marvel had engineered one of the greatest turnarounds in entertainment history – it became the creator of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), the most successful movie franchise ever, culminating in films like The Avengers and Black Panther breaking global box office records. This transformation can be understood through BOS principles, as Marvel effectively crafted a blue ocean at the intersection of comic storytelling and Hollywood filmmaking.

In 1999, new leadership (led by CEO Peter Cuneo) took over Marvel and sought a path out of the red ocean of the comic book publishing business. Marvel’s key realisation was that its treasure trove of 8,000+ characters was an underutilised asset – instead of just licensing these characters to others, Marvel could produce its own films and build a connected universe of stories.

This was a bold strategic move because Marvel had never made movies itself (it usually let bigger studios handle that), and Hollywood was a very different industry with established players. However, it represented Marvel’s blue ocean pivot: entering the motion picture industry in a way that reconstructed how movies could be made and enjoyed.

Rather than make stand-alone films or try to compete with big-budget effects-heavy movies head-on, Marvel created a new concept – a series of movies that were all interlinked in one grand narrative universe. Each film (e.g., Iron Man, Thor, Captain America) stood alone but also built towards larger crossover events (The Avengers). This replicated the experience of comic book story arcs on the big screen, something Hollywood had never done.

Marvel’s strategic move also eliminated or changed some industry norms. Early on, Marvel Studios did not hire the most expensive A-list stars or directors, which kept costs reasonable; instead, it bet on relatively lesser-known actors (at the time, Robert Downey Jr. was a risky pick for Iron Man) and focused on strong character-driven scripts with humour and heart.

Marvel raised the emphasis on long-term character development and cross-film continuity, which attracted not only comic fans but also general audiences who became deeply invested in the ongoing story. It reduced reliance on one-off superstar vehicles (common in Hollywood) and instead built a brand where “Marvel” itself became the draw.

It also created a fan-centric marketing approach – engaging directly with the comic fan community at conventions and online, and adding Easter eggs and post-credit scenes that rewarded loyal viewers. These moves effectively merged the worlds of comics and cinema, appealing to noncustomers of comics (the vast movie-going public) by offering them an accessible entry into the Marvel universe through films.

The value innovation Marvel achieved was providing blockbuster entertainment with a rich, interconnected story world (a novel experience for movie audiences) at a relatively lower risk and cost structure. By the time competitors like DC Comics/Warner Bros. attempted to emulate the cinematic universe approach, Marvel had already locked in millions of fans and a robust production pipeline.

The result: Marvel’s films consistently dominated box office charts. The MCU movies collectively have grossed over $25 billion, and Marvel went from bankruptcy to being acquired by Disney in 2009 for around $4 billion – a deal widely regarded as a bargain in retrospect given the franchise’s earnings. Importantly, Marvel’s strategic move changed the industry: it invented a new formula of franchise filmmaking that others are now following.

The Marvel case illustrates that even in a seemingly saturated entertainment market, a company can break out by reconstructing market boundaries. Marvel shifted from seeing itself as just a comic publisher (a shrinking red ocean) to an integrated entertainment studio that creates markets – converting noncomic readers into superhero movie enthusiasts.

It also underscores that blue ocean strategies often involve viewing your assets differently. Marvel’s characters had been there all along; what changed was how they were leveraged. Through value innovation (stories that combined epic scope and serialised narrative with broad appeal) and by aligning a film studio model to exploit this (including forging its own distribution deals and later leveraging Disney’s muscle), Marvel enjoyed an explosive return to growth.

For much of the 2010s, it had no true peer in its blue ocean – even huge franchises like Harry Potter or Star Wars operate differently. Marvel effectively made the competition irrelevant for a significant period: competitors couldn’t match the depth and fan loyalty of the MCU without years of groundwork.

Need help with a management assignment? Our professional writing service can provide tailored support with essays, reports and case studies at any level. See our management assignment help page for more info.

References and further reading:

- Burke, A., van Stel, A. & Thurik, R. (2010) ‘Blue ocean vs. five forces’, Harvard Business Review, 88(5), pp. 28–29.

- Christensen, C. M. (1997) The innovator’s dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (1997) ‘Value innovation: the strategic logic of high growth’, Harvard Business Review, 75(1), pp. 102–112.

- Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (2004) ‘Blue ocean strategy’, Harvard Business Review, 82(10), pp. 76–84.

- Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (2005) Blue ocean strategy: how to create uncontested market space and make the competition irrelevant. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Google Books

- Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (2017) Blue ocean shift: beyond competing – proven steps to inspire confidence and seize new growth. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

- Kraaijenbrink, J. (2019) ‘Looking for a blue ocean strategy? consider these three risks’, Forbes, 3 September. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeroenkraaijenbrink/2019/09/03/looking-for-a-blue-ocean-strategy-consider-these-three-risks/ (Accessed: 30 September 2025).

- Madsen, D. Ø. & Slåtten, K. (2019) ‘Examining the emergence and evolution of blue ocean strategy through the lens of management fashion theory’, Social Sciences, 8(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010028. MDPI

- The Blue Ocean Team (n.d.) ‘7 powerful blue ocean strategy examples that left the competition behind’, Blue Ocean Strategy (blog). Available at: https://www.blueoceanstrategy.com/blog/7-powerful-blue-ocean-strategy-examples/ (Accessed: 30 September 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: