Value proposition canvas guide

Info: 5835 words (23 pages) Study Guides

Published: 09 Oct 2025

Whether it’s a value proposition canvas or any MBA assignment, our UK-qualified writers can help you deliver work that stands out. See our MBA assignment help page for info.

The value proposition canvas is a strategic management tool that helps organisations design products and services around what customers truly value and need. It was developed by Dr. Alexander Osterwalder as an extension of the Business Model Canvas, focusing in detail on the relationship between a specific customer segment and a product’s value proposition (Osterwalder et al., 2014).

In essence, the canvas forces businesses to think from the customer’s perspective and to ensure there is a fit between the product and the market (B2B International, n.d.). By mapping customer needs (jobs-to-be-done, desired gains, and pain points) against what the company offers (products/services, gain creators, and pain relievers), teams can evaluate how well their value proposition addresses real customer concerns.

This alignment is crucial because it increases the likelihood that a product or service will resonate with its intended audience, thereby improving the chances of achieving product–market fit – a situation where the product satisfies strong market demand.

The value proposition canvas has gained widespread adoption in startups and established companies alike, precisely because it provides a clear, visual framework for iterative product development based on customer insights (Osterwalder et al., 2014).

It is generally used when designing a new offering or refining an existing one, and it encourages an evidence-based, customer-centric approach to innovation. Ultimately, the canvas serves as a practical guide to help ensure that what a business builds is grounded in real value for the customer, rather than in assumptions.

Background and context

The value proposition canvas was introduced in the mid-2010s as part of the Value Proposition Design methodology (Osterwalder et al., 2014). It zooms into two building blocks of the earlier Business Model Canvas – namely, the customer segment and the value proposition (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). By isolating these two elements, the canvas allows teams to study them in greater depth and detail.

The core idea, as explained by Osterwalder, is to design “great value propositions that match your customer’s needs and jobs-to-be-done and help them solve their problems”, thereby working systematically towards what the start-up world calls product–market fit or problem–solution fit (Osterwalder et al., 2014).

In practice, this means that the canvas helps identify whether there is a clear alignment between what the customer needs or wants and what the business is offering. If the alignment is poor, the product is likely to struggle – often manifesting in price sensitivity or lack of customer interest. Conversely, when there is a strong fit, customers perceive high value and are less sensitive to price, improving the business’s competitive position.

The value proposition canvas is therefore fundamentally about mitigating the risk of building something nobody wants, by thoroughly examining customer drivers and tailoring the offering accordingly. Moreover, it complements other innovation techniques (like design thinking and Lean Startup approaches) by providing a structured template to test assumptions and gather feedback.

Indeed, businesses are advised to treat the canvas as a living document – one that is refined continually as new customer insights emerge. By using the canvas, cross-functional teams (from marketing and product to UX design) have a shared language and visual map that fosters customer-centric discussion and decision-making.

This background underlines why the value proposition canvas has become a staple framework in modern business and management education: it bridges theoretical strategy with practical application, helping both students and professionals systematically design value for their customers.

Overview of the canvas structure

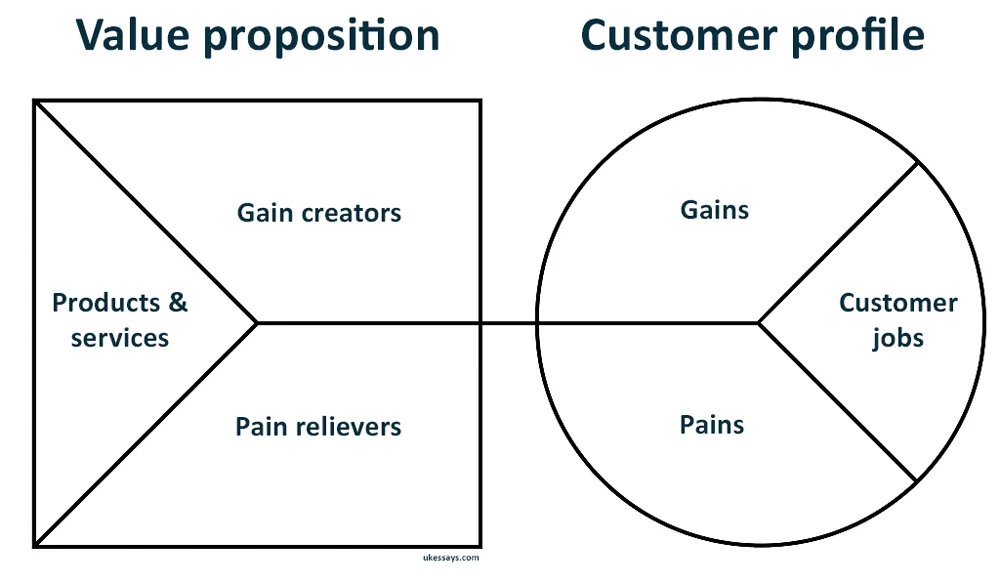

The value proposition canvas is typically illustrated as two connected parts: a Value Map on the left and a corresponding Customer Profile on the right.

Each side contains three key elements, making six in total. The left side (usually shown as a square) represents the company’s value proposition and includes:

(1) Products and services – what the company offers;

(2) Pain relievers – how those offerings alleviate the customer’s pains; and

(3) Gain creators – how they deliver the outcomes or benefits customers desire.

The right side (often drawn as a circle) represents the target customer segment and includes:

(4) Customer jobs – what the customer is trying to achieve;

(5) Pains – the frustrations, obstacles, or risks they face; and

(6) Gains – the positive outcomes or benefits they seek (B2B International, n.d.).

By completing both sides, an organisation can clearly visualise how its offerings create value for a defined customer group.

Download a blank value proposition canvas template to print (PDF).

Each component of the canvas plays a distinct role.

The customer profile side captures an outside-in perspective: it forces you to articulate who your customer is and what matters to them, before thinking about your product.

The value map side then captures the inside-out perspective: it describes how your product or service will deliver value in response to the customer profile.

The power of the tool lies in the comparison between the two sides – it should become immediately apparent where your value proposition is strong, and where it may be lacking or misaligned. In the sections that follow, we explain each component of the canvas in detail and discuss how to effectively populate them.

Components of the Value Proposition Canvas

Customer profile (customer segment)

The customer profile (right side of the canvas) defines a specific customer segment in rich detail. It describes who the customer is and what they are trying to achieve independently of any particular solution.

Notably, a separate customer profile should be created for each distinct customer segment or persona, since different groups will have different jobs, pains and gains.

The profile consists of three elements: customer jobs, pains, and gains.

When analysing a segment, it is often useful to start by brainstorming the customer’s jobs, then identifying pains and gains related to those jobs.

Importantly, the canvas encourages teams to base this profile on research and observation (e.g. interviews, surveys, ethnography) rather than guesswork – initial entries may be hypotheses, but these should be validated with real customers over time.

By clearly delineating jobs, pains and gains, businesses avoid the pitfall of designing an “ideal” customer that simply fits their product, and instead focus on understanding real customers.

The following sub-sections define each part of the customer profile and provide guidance on identifying them.

Customer jobs

Customer jobs represent the tasks, objectives or problems that your customer is trying to address. In other words, these are the underlying motivations or needs that drive the customer’s behaviour (Osterwalder et al., 2014).

Jobs can be functional (practical tasks or problems to solve), emotional (related to feelings or psychological needs), or social (related to how the customer wants to be perceived by others).

For example, if you consider a ride-sharing service’s customer: a functional job might be “get from home to work efficiently,” an emotional job could be “feel safe and comfortable during the ride,” and a social job might be “appear environmentally conscious by using a carpool service.”

It is useful to explore all these dimensions – what the customer is trying to do, why they are trying to do it, and in what context.

Often, you start with an obvious high-level job (e.g. “learn new skills” for a professional taking an online course) and then drill down to deeper motivations (e.g. “to feel confident in my abilities” or “to advance my career”) that underlie that job.

By asking “why?” repeatedly, you uncover additional jobs or refine the understanding of the primary job.

Businesses should list as many significant jobs as they discover, then later rank them by importance to the customer.

Crucially, customer jobs are phrased from the customer’s perspective and in their terms, not as a solution. For instance, a customer job is not “use our app’s features” – rather it’s the goal or task they would achieve irrespective of your product, such as “keep track of my personal finances” or “entertain myself during a commute.”

Customer pains

Pains describe anything that annoys or hinders the customer before, during, or after trying to get a job done. They are the negative outcomes, obstacles, and risks related to the customer’s tasks and goals (B2B International, n.d.).

In essence, pains capture what frustrates the customer or holds them back. These can include undesired costs (e.g. money, time, effort), negative emotions, undesired situations, or any difficulties the customer encounters.

For example, if the job is “keep track of personal finances,” possible pains might include: “It’s time-consuming to consolidate all my expenses manually,” “I worry about making mistakes in my spreadsheet,” or “I feel stressed and guilty when I see how much I spent, which makes me avoid tracking.”

Pains can range from major obstacles to minor inconveniences – it’s useful to list them all, then identify which are most severe or frequent for the customer.

In some cases, pains include barriers that prevent the customer from even attempting a job (e.g. a person might want to exercise regularly but a pain could be “gym memberships are too expensive” which stops them from pursuing the job of “stay fit”).

They can also include risks the customer fears (for instance, “if I adopt this new software, I fear it might fail or I could lose data”).

To systematically uncover pains, ask questions like: What makes the job difficult or unpleasant for the customer? What are the main sources of cost, stress, or irritation? What could go wrong and cause loss or embarrassment?

By identifying pains, we pinpoint the problems that our value proposition might need to solve or alleviate.

It’s worth noting that pains should be described in the customer’s terms, as specific as possible, and not inadvertently bias towards our solution. For example, instead of saying “customer finds it hard to use our interface” (which references our product), frame it as “customer finds technology confusing” or “customer lacks time to learn complex tools” – a genuine pain that exists regardless of our specific solution.

Customer gains

Gains are the positive outcomes and benefits that the customer desires or would be delighted by. They represent what the customer hopes to achieve or get as a result of doing the job.

Gains can include required outcomes (basic expectations), expected benefits (the standards that must be met), desired gains (what customers would love to have), and even unexpected delights (features or outcomes that could surprise and impress them) (Medium, 2020).

Importantly, gains are not simply the mirror-opposites of pains. In other words, if a pain is “it takes too long to do X,” the corresponding gain is not just “it is quick to do X” – that quickness might be expected; a true gain might be “I save so much time doing X that I can accomplish additional goals” or “I feel peace of mind because X is handled automatically.”

To identify gains, consider what would make the customer’s job easier, what they would consider beyond satisfactory, and what would exceed their expectations. Ask questions such as: What do customers truly want to accomplish or experience? How do they measure success or failure in this task? What would increase their likelihood of adopting a solution? What would delight them? (Medium, 2020).

For a personal finance tracking example, gains could include: “having a clear real-time view of my spending (so I feel in control)”, “saving money by spotting wasteful expenses”, or “earning rewards or insights that motivate me to stick to my budget”.

Gains can also touch on emotional and social aspects: e.g., “feeling proud and responsible about my finances,” or “being seen as financially savvy by my family.”

As with pains, it’s useful to list many potential gains and then identify which ones are essential versus merely nice-to-have.

Minimum required gains are those without which the solution would fail (for instance, if a budgeting app doesn’t reliably track expenses, that basic gain of accuracy must be there).

Beyond that, ranking gains by importance can guide which benefits your value proposition should focus on delivering.

Value Map (value proposition)

The value map (left side of the canvas) describes how the product, service or solution creates value for the customer. It is the counterpart to the customer profile, and it also consists of three elements: the list of Products and services the company provides, the Pain relievers that address customer pains, and the Gain creators that generate customer gains.

When producing the value map, it is crucial to keep the previously identified customer profile in mind – the aim is to directly map the product’s features and benefits to the customer’s jobs, pains and gains.

Unlike the customer side, which might include a long list of jobs/pains/gains, the value map is typically more focused: it should highlight the few offerings and features that are most relevant to the target customer’s needs.

Trying to solve every pain or deliver every imaginable gain can lead to a diluted value proposition, so prioritisation is key. As a rule of thumb, a strong value proposition doesn’t necessarily address all customer jobs, pains, and gains – but it absolutely must nail the most important ones.

In this section, we break down how to articulate each part of the value map, ensuring that they clearly tie back to the customer profile.

Products and services

This element is a simple list of what you offer as part of your value proposition. It includes your core product or service, as well as any ancillary products, features, or services that add value.

For instance, if we take the example of an online learning platform, the products and services might include: a library of video courses (core service), downloadable study materials, a mobile app, a community forum, and perhaps one-on-one mentoring sessions as a premium offering.

It’s important to list everything you provide that has relevance to the customer’s jobs, pains, or gains. Products can be tangible (a physical item like a laptop), intangible (consulting, training), digital (software, an app, online platform), or financial (e.g., a line of credit) – any category of offering.

If your value proposition includes multiple products or features, you may also indicate which are the most important to the customer. For example, a design professional might value “high-quality advanced design courses” over “beginner courses” if they are already experienced.

By ranking the items, you communicate which aspects of your offering you believe are most valuable to the target customer. This list should directly correlate with the customer’s jobs: each product or feature is there for a reason – ideally, to help the customer get a job done or to address a pain or gain. If you find elements in your product that do not map to any customer need, it may signal an unnecessary feature. Conversely, if a crucial customer job has no product or feature addressing it, that gap is worth noting. Thus, the Products and Services section establishes the groundwork: it is the “raw materials” of your value proposition, which you will then evaluate through the lenses of pain relievers and gain creators.

Pain relievers

Pain relievers detail how your products and services alleviate the specific pains that the customer profile identifies.

In this section, each pain reliever corresponds to one or more customer pains. You should explicitly describe how a feature or aspect of your offering reduces or removes a frustration your customer experiences.

Strong pain relievers either eliminate a pain entirely or significantly reduce it to a level the customer finds acceptable.

Some pain relievers are straightforward fixes: for example, if a pain is “too time-consuming,” a pain reliever could be an automation feature that saves time.

If a pain is “high cost,” a pain reliever might be a more affordable pricing model or a cost-saving mechanism introduced by your service.

Other pain relievers might address emotional pains, such as providing reassurance (e.g., a free trial or money-back guarantee to relieve the fear of wasting money on a new product) or addressing social pains (e.g., a feature that allows users to share achievements, alleviating the fear of lack of recognition).

When brainstorming pain relievers, it’s helpful to revisit each major pain and ask: “What could we do, through our product or service, to make this pain less painful or irrelevant?”. For instance, if customers worry about a platform’s reliability (a pain: “What if the system is down when I need it?”), a possible pain reliever is a strong uptime guarantee or offline functionality.

It’s crucial to be realistic and honest here: not every pain can be entirely eliminated, and overstating your ability to relieve pains can lead to disappointment. Osterwalder notes that you must remain objective – identify which pains you can relieve well, and also acknowledge pains that your product will not address . This clarity prevents overpromising.

Once listed, pain relievers can be ranked by how well they resolve big pains. For example, if “lack of time” was the customer’s top pain, and your product’s key pain reliever is “it’s 50% faster than the current solution,” that’s a critical part of your value proposition.

On the other hand, if there’s a minor pain that you only partially alleviate, that would be a lower priority.

Gain creators

Gain creators describe how your products and services produce outcomes or benefits that match the customer’s desires. They directly map to the gains in the customer profile, showing how you intend to deliver or enable those benefits.

A gain creator can either provide an expected benefit better than current alternatives or introduce an unexpected delight that the customer did not anticipate.

For example, if a desired gain is “save money on energy bills,” a gain creator might be “our device automatically optimises power usage to reduce bills by 20%.”

If an unexpected gain could be “feel part of a community,” a gain creator might be “built-in social sharing and community challenges to engage with other users.”

Essentially, gain creators answer the question: “How does our offering make the customer’s life or work better? What new positive outcomes can we enable?”.

Much like with pains, it’s important not to confuse gains with merely the absence of pain.

For instance, removing a hassle is covered under pain relievers, whereas gain creators should highlight additional benefits or enhancements.

Take, for instance, a food delivery service: removing the pain of “long wait times” is a pain reliever (fast delivery). A gain creator, however, could be “ability to track your order in real time,” which adds convenience and peace of mind – it’s a positive feature that goes beyond just being less slow.

Gain creators might address functional improvements (better performance, higher quality, more choices), social benefits (status, network effects), or emotional benefits (fun, well-being, satisfaction).

It can help to classify gain creators as those that fulfill expectations (the basics that customers would be happy to have) versus those that create excitement (innovative extras that customers wouldn’t expect but love once they experience them).

Once listed, you should again prioritise which gain creators are most important to communicating your value. Ideally, your product’s top gain creators align with the customer’s top desired gains.

For example, if customers highly value “feeling secure about data,” then a gain creator like “end-to-end encryption and privacy controls” would be a core part of your proposition.

Gain creators, together with pain relievers, form the crux of how you differentiate your offering. They are often the source of your marketing messages (“Not only do we solve your problem X, we also deliver Y that you’ll love”). A strong set of gain creators ensures that your product doesn’t just neutralise negatives, but actively contributes positives to the customer’s life or business.

Achieving fit between customer and value proposition

A primary purpose of the value proposition canvas is to assess fit – the degree to which the product’s value map aligns with the customer’s profile. Achieving what is often termed problem–solution fit (or at a larger scale product–market fit) means that the most important customer needs are being effectively addressed by the offering.

In practical terms, a fit is achieved when the products and services cover the customer’s key jobs, when the pain relievers tackle the customer’s most severe pains, and when the gain creators deliver the most desired gains.

Not every single pain or gain must have a corresponding feature – rather, the focus is on the critical ones. A useful exercise after populating both sides of the canvas is to rank or rate each item by importance (on the customer side) and by your ability to deliver (on the product side).

For example, you might mark each pain and gain as “essential”, “important” or “nice-to-have” from the customer perspective. Similarly, mark your pain relievers and gain creators by how effectively they address those needs (perhaps in terms of impact level).

You then look for matches: does every “essential” pain have a strong pain reliever? Are the top three gains the customer cares about actually being created by our proposition? If you discover gaps – e.g., a top customer pain is not addressed – that indicates a potential weakness in the fit.

If you find mismatches – e.g., you have a pain reliever for a pain the customer doesn’t actually rank highly – that might be an overinvestment in a trivial area. The sweet spot is where your value map corresponds to the highest priorities of the customer profile (Netguru, 2025). At that point, customers will feel that the product was practically tailor-made for them.

It’s also insightful to consider degrees of fit: complete alignment is rare, especially early on. If some lower-priority jobs or minor pains aren’t addressed, it may be acceptable; what matters is that no significant unmet needs remain.

For instance, if a product addresses 8 out of 10 customer needs extremely well, and the remaining 2 are relatively minor, customers may still perceive a strong fit. On the other hand, if even one crucial job or pain is neglected, that can undermine the overall value in the customer’s eyes. Thus, part of the strategy might be to either improve the product to cover that gap or to refine the target segment if you find you cannot serve that need and maybe there’s a segment that doesn’t have that particular requirement.

Achieving fit is not a one-time static milestone either: markets evolve and customer preferences shift. This is why after achieving an initial fit, businesses must continuously gather customer feedback and iterate. Often, the canvas is revisited and updated after testing the value proposition with real customers – if evidence shows that certain assumptions were wrong, the canvas can be adjusted to better reflect reality. By iterating in this way, the canvas becomes a dynamic tool guiding the product toward deeper and more resilient product–market fit over time.

How to use the Value Proposition Canvas (step-by-step)

Using the value proposition canvas is an iterative and thoughtful process. Here is a step-by-step guide on how to create and utilise a value proposition canvas effectively:

Define your target customer segment.

Start by clearly identifying who your canvas will focus on. It could be a specific user persona or market segment. Be as concrete as possible (e.g., “urban professionals aged 25–35 who commute by bicycle” or “IT managers in mid-sized firms looking for cybersecurity solutions”).

If your business has multiple customer segments, you should create separate canvases for each, as their needs will differ. Choosing one canvas per segment ensures clarity and avoids mixing needs across disparate audiences.

Outline the customer’s jobs-to-be-done.

Begin filling in the Customer Jobs for that segment. Ask yourself what tasks the customer is trying to accomplish, what problems they aim to solve, and what needs they seek to satisfy. List both the obvious, functional jobs and the less obvious emotional or social jobs.

A helpful technique is to conduct customer interviews or surveys at this stage, so you base the jobs on real insights. Write down all significant jobs in the customer’s own terms. (For example, a customer’s jobs might be “keep my family safe while driving” and “enjoy the driving experience”.)

Identify customer pains.

Next, enumerate the Pains the customer experiences in relation to those jobs. Think about what could go wrong, what annoys or frustrates the customer, and what barriers might be preventing them from achieving their jobs. Use direct evidence where possible – e.g., complaints customers have voiced or observed difficulties. Include pains before, during, and after the job.

Each pain should be tied to a job or context. (For instance, pains could include “high cost of car insurance,” “fear of accidents,” or “difficulty in finding parking” if we continue the driving example.) Aim to capture both big and small pains, then later mark which pains are primary (the ones that would make a customer really eager for a solution) versus secondary.

List customer gains.

Now, list the Gains that the customer expects or desires. These are the positive outcomes they hope for – both the essentials and the pleasant surprises (Medium, 2020). Consider what success looks like for the customer, what would delight them, and what other benefits they would value.

Again, draw from customer input if available (e.g., “I wish it also did X!” remarks). (In our example, gains might be “lower monthly car-related expenses,” “peace of mind about my family’s safety,” “enjoyable commute time (maybe listening to music or podcasts),” or “some recognition for being an eco-friendly driver.”) Once listed, distinguish must-have gains (things the solution must deliver to be considered adequate) from nice-to-have gains (additional perks that would make it even better).

Prioritise the jobs, pains, and gains.

With a comprehensive list of jobs, pains, and gains, the next step is to prioritise them from the customer’s perspective. Not all items are equally important. Use whatever data you have – frequency of mentions, severity, or your knowledge of the customer context – to rank them.

One common approach is to rank pains and gains on a scale (e.g., 1 to 10) or simply tag them as “critical,” “important,” or “minor.” Prioritisation is crucial because it informs which aspects your value proposition should focus on. For example, if you determine the top pain is “difficulty in finding parking”, and a lesser pain is “high insurance cost,” your solution should probably address parking first and foremost. This ordered list of customer needs will act as a compass for designing the value map.

Draft the products and services (your offering).

Shift to the left side of the canvas. List your Products and Services – essentially, what you propose to offer to this customer. If you already have a product, list its main components and features. If it’s a new concept, list the planned features or services that will form the solution.

Be specific but not overly technical (the focus is on value, not specifications, at this stage). (For instance: “a mobile app for drivers,” “real-time navigation with parking spot finder,” “integrated insurance offers,” etc.) Ensure you include any service components too (e.g., customer support, maintenance, community forum, etc.), as these can contribute to value.

Brainstorm pain relievers for each major pain.

For each of the high-priority customer pains from step 5, consider how your product or service could relieve that pain. Write down the corresponding Pain Relievers in the canvas. Each pain reliever should explicitly connect to a pain.

Use active language to describe how it helps. (Continuing the example: if a pain is “finding parking is difficult,” a pain reliever might be “the app shows available parking spots in real time and reserves one for the driver.” If a pain is “fear of accidents,” a pain reliever could be “the car has advanced safety features with automatic emergency braking.”)

If some pains cannot be addressed by your current offering, note that gap – it might be acceptable (if it’s a minor pain) or it may highlight an area for future improvement or a need to adjust your target segment. Avoid the temptation to claim a pain reliever for every single pain if it’s not credible; focus on where your solution genuinely shines.

Ideate gain creators for the key gains.

Next, for each important gain identified, outline how your product can create those gains. List these as Gain Creators on the canvas. Each gain creator is essentially a feature or element of your offering that produces a benefit.

(For example: for the gain “peace of mind about safety,” a gain creator might be “24/7 roadside assistance included via the app,” or “insurance discounts for safe driving habits,” which give the customer extra reassurance. For the gain “enjoyable commute,” a gain creator could be “built-in entertainment system” or “rewards points for eco-friendly driving that can be redeemed for freebies,” adding an element of fun or satisfaction.)

Be imaginative but keep the customer’s perspective; the gain creator must be something the customer will recognise as a benefit. Also, ensure it’s plausible – ideally based on capabilities you either have or can develop. Not every desired gain will have an immediate gain creator in your current product; that’s okay. What’s important is covering the top gains in some way.

Review and refine the fit.

Now step back and compare the two sides of your canvas. Draw explicit lines or make notes linking each pain to its reliever and each gain to its creator. Where you have a strong match – say a top pain “X” and you have a feature that directly addresses X – that’s a highlight of your value proposition. Where you see a pain or gain with nothing addressing it, decide if it’s something you can safely ignore (maybe it’s a low priority issue) or if it’s a critical gap.

Similarly, you might find you have a feature that doesn’t clearly map to any pain or gain – this might indicate an “extra” that isn’t adding value for this customer, which could be de-prioritised or reframed. At this stage, you may need to iterate: possibly revisiting your understanding of the customer or reconsidering your product features.

The aim is to achieve a coherent story where the product exists because of these customer needs, and conversely the customer’s needs are largely met by this product. If the puzzle pieces aren’t fitting, iterate through steps 1–8 again: it may involve narrowing the customer segment further, doing more customer research, or tweaking the product concept.

Test and validate with customers.

Treat the completed canvas as a hypothesis of value. Especially if this is a new offering, it’s crucial to validate the assumptions you’ve mapped. This can be done through customer interviews, surveys, or prototype testing.

Present prospective customers with your value proposition (the pains you aim to solve and gains you promise) and gauge their reactions: Do they confirm these are real pains/gains for them? Are they excited by the reliefs and benefits you propose?

This step often leads to new insights – for example, you might discover an additional pain you overlooked, or that a gain you thought was important is actually not valued by customers. Use this feedback to refine the canvas. In some cases, you might iterate multiple times: adjusting the product features or even shifting to target a different job or segment if the fit isn’t resonating.

Over time, this build-measure-learn cycle will strengthen the fit. For existing products, this step might involve analysing usage data or customer feedback to see if the value proposition holds true in practice. The canvas can be a living document, updated as you learn more.

Align the team and integrate into strategy.

Once you are confident in a strong value proposition canvas, use it as a communication tool. Share it with stakeholders, from design and development teams to marketing and sales. It ensures everyone understands who the product is for and why it will matter to them.

This alignment helps in making consistent decisions – for instance, marketing campaigns can be tailored to highlight the very pains and gains identified, and designers can focus on the features that serve those needs best.

Additionally, the canvas can guide what not to do: if a feature idea comes up that doesn’t fit the canvas, the team can question whether it’s necessary or if it’s targeting a different segment.

By integrating the canvas into your product development and business strategy, you maintain a customer-centric focus. Remember, the canvas should be revisited whenever there is a significant change – such as exploring a new customer segment, responding to competitor moves, or after a major round of customer feedback. It’s a tool not just for initial design but for continuous value exploration.

Using the value proposition canvas in this methodical way helps ensure that each step of product or service development is grounded in real customer insight and clear value creation logic. It’s both a diagnostic tool (to identify misalignments) and a creative tool (to inspire solutions to customer problems). Moreover, it’s quite adaptable: whether you are a startup founder sketching an idea on paper or an innovation team at a large company refining a product strategy, the canvas provides a common framework to brainstorm and evaluate ideas systematically.

Get expert help with any MBA assignment from UK-qualified writers who know what top universities expect. Whether it’s a value proposition canvas or any MBA assignment, our UK-qualified writers can help you deliver work that stands out. See our MBA assignment help page for info.

References and further reading:

- B2B International (n.d.) What is the Value Proposition Canvas? [Online]. Available at: https://www.b2binternational.com/research/methods/faq/what-is-the-value-proposition-canvas/ (Accessed: 9 October 2025).

- Interaction Design Foundation (2025) The Value Proposition Canvas. [Online]. Available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/value-proposition-canvas (Accessed: 9 October 2025).

- Medium (2020) Value proposition canvas: comprehensive guide with examples. [Online]. Available at: https://medium.com/awware/value-proposition-canvas-comprehensive-guide-with-examples-88e785c4e15e (Accessed: 9 October 2025).

- Netguru (2025) How the Value Proposition Canvas Can Help Achieve Product-Market Fit. [Online]. Available at: https://www.netguru.com/blog/value-proposition-canvas (Accessed: 9 October 2025).

- Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010) Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Bernarda, G., Smith, A., and Papadakos, T. (2014) Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Strategyzer (2025) The Value Proposition Canvas – Download the Official Template. [Online]. Available at: https://www.strategyzer.com/library/the-value-proposition-canvas (Accessed: 9 October 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: