Ansoff matrix examples + guide

Info: 3707 words (15 pages) Study Guides

Published: 24 Sep 2025

Part of: Ansoff Matrix

Need help with a undergraduate or MBA management assignment? Our UK-qualified management experts are ready to assist. Visit our management assignment help page now for more info.

The Ansoff Matrix is a strategic planning tool that helps organisations map out options for business growth through products and markets. Developed by Igor Ansoff – often called the father of strategic management – it was introduced in a 1957 Harvard Business Review article (Ansoff, 1957).

Despite its mid-20th century origin, the framework remains highly relevant and is still taught worldwide in business and marketing programmes.

It provides a simple yet effective way for managers and marketers to conceptualise growth strategies and assess the associated risk. By structuring strategic options along two key dimensions – product (existing vs. new offerings) and market (existing vs. new customer markets) – the matrix generates four distinct growth strategies, each with a different risk profile.

This guide offers a comprehensive look at Ansoff’s matrix, explaining each strategy in turn and illustrating them with real-world examples. It also discusses how to apply the matrix in practice, and reflects on its benefits and limitations in modern strategic planning.

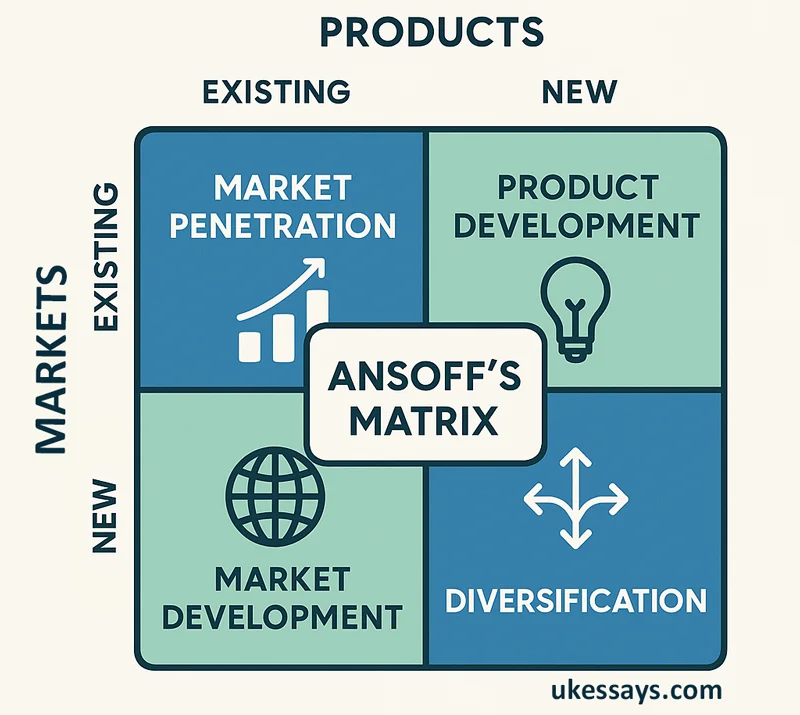

Structure of the Ansoff Matrix

At its core, Ansoff’s matrix is a 2×2 grid that juxtaposes products and markets. The horizontal axis distinguishes between existing products and new products, while the vertical axis separates existing markets from new markets.

Each of the four quadrants of this grid corresponds to a specific growth strategy:

- Market Penetration

- Product Development

- Market Development, and

- Diversification.

Moving to a new product or a new market generally entails greater uncertainty, so each step away from the top-left quadrant (existing product in an existing market) increases the level of risk.

The matrix thus not only generates strategic options but also highlights their relative risk: expanding within current domains is usually safer, whereas venturing into new products and new markets simultaneously is the riskiest approach.

This structured view helps decision-makers evaluate potential growth paths in light of their organisation’s capabilities and external market conditions. Indeed, managers often use the Ansoff Matrix alongside other analytical frameworks – such as SWOT, PESTEL or Porter’s Five Forces – to ensure that chosen growth strategies align with the business environment and the firm’s strengths.

Below, we examine each of the four Ansoff strategies in detail and discuss when and how they can be employed.

Market penetration

Market penetration is the strategy of increasing sales of existing products in existing markets.

This is Ansoff’s least risky growth option because the business is operating in familiar territory with proven products and known customers.

The firm leverages its existing competencies and market insights, so there are fewer unknowns compared to strategies involving new products or markets.

Companies pursuing market penetration aim to deepen their presence in the current market – for example, by boosting market share or encouraging greater usage of their product among current customers.

Typical tactics include intensifying marketing and promotional efforts, optimising pricing to attract more buyers, expanding distribution within the market, or even acquiring smaller competitors to quickly gain share.

Because the product and audience remain the same, the focus is on outcompeting rivals and capturing a larger slice of the existing demand.

However, the scope of market penetration is inherently limited by the market’s growth potential.

This strategy works best when the overall market is still growing or when a company can differentiate itself and draw customers away from competitors.

If the market is saturated or stagnant, aggressive penetration efforts (such as price cuts or heavy advertising) might only yield gains by cannibalising competitors’ share, which can provoke retaliatory actions.

Still, many firms find market penetration attractive as an initial growth step because it capitalises on what the business already does well, with relatively low risk.

Example: The Coca-Cola Company has repeatedly used market penetration tactics in its established markets – increasing advertising spend, running big promotional campaigns, and widening its distribution network – to boost sales of its existing beverage products in markets where it is already present. By doubling down on marketing and execution in its current markets, Coca-Cola has been able to reinforce its market leadership and generate growth without venturing into unfamiliar products or territories.

Product development

Product development is a growth strategy that entails introducing new products to an existing market (Ansoff, 1957).

Here, the company remains within its current customer market but seeks to increase growth by offering innovative or additional products that complement or replace its existing line-up.

This strategy is common when a firm has a strong brand and loyal customer base – it can leverage that goodwill and understanding of customer needs to launch new offerings. Because the market is known, the primary challenges lie in product innovation and development.

Risk is moderate: higher than simply selling more of current products (since developing new products can fail or incur high costs), but lower than diversification (since the customer base and channels are already established).

Effective product development requires significant investment in research and development, careful study of customer preferences, and often enhancements to marketing and support capabilities to roll out the new product successfully. The firm must ensure that the new product meets the quality expectations of its existing customers and fits the brand’s image, because a misstep can disappoint loyal buyers and squander goodwill.

Several tactics can drive product development. A company might undertake its own R&D to invent genuinely new products, or it could acquire rights to produce another company’s product, or even collaborate with third-party manufacturers (e.g. private labeling) to quickly expand its product range.

Throughout this process the firm benefits from its market knowledge – for instance, by engaging with current customers to solicit feedback on new product ideas and by leveraging existing distribution and sales networks to launch the product.

Example: A classic example of product development is Apple Inc. continually introducing new products and services to its loyal customer base. Over the years, Apple has expanded beyond its original Mac computers to music players, smartphones, tablets, wearables, and streaming services, all targeted at essentially the same market of Apple enthusiasts. By innovating new offerings like the Apple Watch and AirPods for its existing users, Apple has grown revenue per customer and strengthened customer loyalty.

Another theoretical example might be a cosmetics brand known for skincare that develops a new line of makeup for its current clientele – it relies on brand trust and existing market presence, but must invest in creating and marketing an appealing new product line. Product development thus allows companies to grow “horizontally” within their current market, deepening the value they provide to customers, but it demands creativity and rigorous execution to succeed.

Market development

Market development is the strategy of entering new markets with existing products. In this scenario, a company takes what it already excels at – its current products or services – and seeks to expand into new customer segments or geographic regions that it has not served before (Ansoff, 1957).

Because the product remains unchanged, the assumption is that it has proven value; the growth challenge is to replicate the business’s success in a new market environment.

This strategy can unlock significant new revenue streams, for example by introducing products to untapped regional markets or new demographic groups, but it carries uncertainties related to the unfamiliar market.

Managers must research and understand the local conditions, customer preferences, and competitive landscape of the new market to ensure their existing product will be accepted. As a result, market development often requires adjustments in distribution and marketing strategies: the product might need minor adaptations to meet local tastes or regulations, and promotion must be targeted to resonate with a new audience.

Key elements of the marketing mix that tend to change include “Place” (e.g. establishing new distribution channels or retail presence) and “Promotion” (crafting new messaging or campaigns for the new segment).

Compared to market penetration, the risk is higher here because the company is stepping into the unknown to some degree. There may be cultural differences, different customer needs, or strong incumbent competitors in the new market.

However, unlike product development, a market development strategy does not demand heavy R&D investment since the product is already developed and tested – the risk and cost lie in market entry and expansion efforts.

Often, firms pursue market development once domestic or core market growth opportunities dwindle; expansion can be domestic (targeting a new region or city) or international.

Example: When Netflix reached saturation in its home market, it pursued aggressive international expansion, bringing its existing streaming service to markets across Europe, Asia, and Latin America. Netflix had to invest in understanding local content preferences and adjusting its offerings (such as adding region-specific films or enabling new language options), but it leveraged the same core product platform.

Example: Another example is Starbucks entering markets like China and India with its coffeehouse concept – the product (coffee beverages and cafe experience) remained fundamentally the same, but the company adapted store formats and menus to local tastes and built brand awareness from scratch in new countries.

Thus, market development allows a proven product to fuel growth by finding new customers, but success requires careful market research and often incremental adaptation to bridge the gap between old and new markets.

Diversification

Diversification is the strategy of developing new products for new markets – effectively the most radical option, involving two dimensions of change simultaneously (Ansoff, 1957).

Because the firm is moving into unfamiliar product lines and targeting customers it hasn’t served before, diversification inherently carries the highest level of risk among the four Ansoff strategies.

Not only must the company invest in creating or acquiring new product capabilities, it must also build knowledge and presence in a new market space.

The appeal of diversification is that it can open entirely new avenues of growth and, if successful, significantly reduce dependence on the original business. In some cases, diversification is pursued to achieve high growth when other strategies are exhausted, or as a defensive move to spread risk across different industries (for instance, to hedge against a declining core market).

Diversification comes in two forms: related diversification and unrelated diversification.

In related diversification, the new product/market has a meaningful connection to the company’s existing business – for example, a firm can leverage technical know-how, supply chain synergies, or brand reputation from its current operations.

A classic scenario might be a leather footwear manufacturer diversifying into leather accessories or automobile upholstery: the products differ, but they draw on shared materials and manufacturing expertise, making the new venture somewhat less daunting due to these synergies.

In contrast, unrelated diversification means venturing into an entirely different industry or market where the firm has little prior experience or overlap. This could be likened to a complete corporate pivot – for instance, a software company acquiring a chain of fitness centres would be unrelated diversification.

Unrelated moves can yield high rewards if they tap into lucrative sectors, but they are extremely challenging because the company must acquire new competencies and cannot rely on its existing brand or expertise to the same extent.

Given these challenges, a diversification strategy demands thorough due diligence and strategic planning. Companies should carefully assess the potential returns and ensure they have (or can acquire) the resources and talent required for the new venture.

Often, diversification is achieved via mergers and acquisitions – buying an existing player in the target industry – or by creating a new business unit from scratch.

Example: As an example of successful diversification, Amazon.com expanded from its original domain of e-commerce retail into cloud computing services with Amazon Web Services (AWS), and into digital entertainment with Amazon Prime Video. These moves represent new products targeting new markets (enterprise IT clients for cloud services, and global streaming audiences for video content), distinct from Amazon’s original online bookstore business. Over time, AWS became a huge growth driver and a completely new line of business for Amazon, illustrating how diversification can yield significant rewards.

It is worth noting that Amazon’s diversification, while drastic, still drew on some related capabilities – for instance, the company’s strength in IT infrastructure and its large customer base – making it closer to related diversification.

Example: Another well-known example is Virgin Group, which under Richard Branson branched out from a record label into airlines, rail, telecoms, and more. Virgin leveraged its brand and customer service ethos across industries (related in spirit, if not in technical skills), though not all ventures succeeded.

In practice, diversification is the most uncertain growth path, but when executed well, it can transform a company’s scope and long-term trajectory. Managers must weigh the potential high rewards against the substantial risks and often pursue diversification only after careful consideration or in response to clear market opportunities that justify the leap.

Applying the Ansoff Matrix in strategic planning

The Ansoff Matrix is not just a theoretical construct – it serves as a practical guide in the strategic planning process. To effectively use the matrix for decision-making, managers typically follow a structured approach that ensures all options are considered and aligned with the company’s goals.

First, the organisation should assess its current situation – evaluating existing products, market share, customer segments, and core competencies. This establishes a baseline of what is working well and where there are gaps or untapped opportunities.

Next, the team should brainstorm potential growth opportunities in each of the four Ansoff quadrants. At this stage, creativity is encouraged: for example, they might list ideas for expanding market penetration (such as new promotions or loyalty programs), possibilities for product development (new product features or line extensions that current customers might want), markets that could be developed (new regions or niches that resemble their current market), and diversification ideas (completely new product-market combinations that fit the company’s vision).

Then, each option must be evaluated in terms of its attractiveness and risk. It’s crucial to research the market demand, competitive landscape, and feasibility for each idea. Managers will ask questions like: How large is the new market and who are the competitors? What investment would a new product require and does the firm have the technical capability? What are the risks if we stay in our current market vs. venture out? At this point, using the matrix helps visualise the relative risk: opportunities in the top-left (market penetration) tend to be safer but perhaps lower in potential reward, whereas bottom-right (diversification) ideas could be game-changers but are riskier.

After assessing options, the organisation can prioritise growth strategies that best balance risk and reward in line with its objectives. For instance, a firm might decide that a product development strategy (moderate risk, moderate reward) aligns well with its strengths in R&D and its strategic goal of increasing customer lifetime value, whereas a diversification idea, though interesting, is set aside for now due to high uncertainty.

Once a strategy (or combination of strategies) is chosen, the next step is to develop a detailed implementation plan. This plan should outline how the strategy will be executed – including resource allocation, timelines, and specific tactics.

For example, if market development is chosen, the plan may detail the steps to enter the new market: hiring a local sales team, adapting the product if needed, marketing campaigns for awareness, and so on. It will also set measurable objectives (such as market share or revenue targets in the new market within a certain timeframe). Finally, no strategy is static: continuous monitoring and adaptation are essential.

As the strategy is rolled out, management should track progress against KPIs and be ready to adjust the approach based on feedback and changing conditions. For instance, early response in a new market might reveal the need to tweak the product or messaging, or a new competitor’s move might require a change of tactics.

Benefits and limitations of the Ansoff Matrix

Strengths

The enduring popularity of Ansoff’s matrix in management circles is largely due to its clear and practical benefits.

First, it offers strategic clarity: the model simplifies a complex question (“How can we grow?”) into four digestible categories.

This clarity helps managers and students alike to ensure that all fundamental growth avenues are considered. It prompts discussions around whether to deepen current operations or branch out, and it forces a conscious evaluation of the status quo versus new ventures.

Second, the matrix sharpens risk awareness. By conceptually mapping strategies from least to most risky, it encourages decision-makers to weigh the potential rewards of a strategy against its uncertainties.

For example, executives using the matrix will recognize that an ambitious plan to launch a brand-new product abroad (diversification) carries far more risk than selling more of an existing product to loyal customers (penetration). This doesn’t mean the risky option is never chosen, but the choice will be informed by an understanding of risk trade-offs.

Third, the Ansoff Matrix supports a structured approach to strategic planning. It ensures that discussions are comprehensive (covering internal product development and external market expansion) and that strategies are aligned with the firm’s overall objectives.

In practice, the matrix is highly versatile – it can be applied to organisations of any size or industry, and to both corporate strategy and marketing strategy contexts. Its simplicity makes it a useful communication tool as well: managers can easily present the four options to stakeholders and explain the company’s chosen growth path in these terms.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, it is important to acknowledge the limitations and criticisms of the Ansoff Matrix. Perhaps the most cited limitation is that the model is simplistic – it reduces the rich variety of growth possibilities into a binary classification of products and markets. Real-world business environments are more complex and fluid than a static 2×2 grid can capture.

Markets and products are not always clearly defined or independent; in reality, growth initiatives often span multiple categories.

For example, a company’s strategy might blur the lines: launching a **“new” product that is only slightly modified from an existing one while entering a somewhat new market that overlaps with the current market.

In such cases it’s debatable whether this is product development, market development, or a bit of both. Scholars have noted that the strict division of the matrix can be problematic – John Dawes (2020) argues that if a truly new product inevitably appeals to a new market, then pure product development (new product, same market) is sometimes an unrealistic scenario, effectively merging into diversification (Dawes, 2020).

Conversely, if a company can introduce a new product within its current market without venturing into a new one, then “new product + new market” (diversification) might not always imply as radical a departure as the model assumes (Dawes, 2020). These logical nuances suggest that managers should use the matrix as a starting point, but not as a strict algorithm.

Another limitation is that the Ansoff Matrix is inherently static. It presents growth options at a point in time, whereas in practice, strategy is dynamic and evolutionary.

Successful companies often sequence their growth moves – for instance, start with market penetration to build strength, then use that base to develop products, and only later diversify.

The matrix itself does not indicate any time dimension or sequence, so it doesn’t directly guide managers on which strategy to pursue first or how one leads to another. Managers must overlay their judgment and perhaps use other frameworks to map out a roadmap over time.

Additionally, the matrix doesn’t explicitly incorporate external factors like competitor reactions, regulatory changes, or technological disruptions. This is why integrating Ansoff’s analysis with broader environmental scanning (PESTEL for macro factors, Five Forces for industry competition, etc.) is advisable.

Finally, critics note that the Ansoff Matrix assumes decision-makers will choose a single strategy or at least consider them separately, but reality may require creative combinations and flexibility.

Strategic growth is not always a neat choice of one of four boxes; sometimes a company finds ways to, say, develop a new product that also opens a new market – a hybrid strategy. Managers must be careful not to let the matrix constrain thinking. In other words, the tool is prescriptive in framing options, but strategy formulation often requires going beyond the basics and considering hybrid or incremental approaches.

Wrapping up:

More than six decades after its conception, Ansoff’s matrix continues to be a cornerstone framework in strategic management and marketing planning. Its enduring appeal lies in distilling the essence of growth strategy into an accessible format that forces clarity about a firm’s options. By evaluating whether to seek growth through current or new products, and in current or new markets, organisations can ensure they have scanned the full spectrum of opportunities.

Each of the four strategies – market penetration, product development, market development, and diversification – comes with distinct opportunities, challenges, and risk levels. There is no one “right” answer for all companies; the optimal growth path depends on the firm’s objectives, resources, market conditions, and appetite for risk. Ansoff’s matrix guides leaders and students to make these considerations explicit. It is noteworthy that many successful companies employ multiple Ansoff strategies over time, reflecting how the matrix can inform a long-term growth roadmap rather than a one-off choice.

Need help with a undergraduate or MBA management assignment? Our UK-qualified management experts are ready to assist. Visit our management assignment help page now for more info.

References and further reading:

- Ansoff, H. I. (1957) Strategies for Diversification, Harvard Business Review, 35(5), pp. 113–124.

- Corporate Finance Institute (n.d.) Ansoff Matrix – Overview, Strategies and Practical Examples. Available at: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/management/ansoff-matrix/ (Accessed 24 September 2025).

- Dawes, J. (2020) The Ansoff Matrix: A Legendary Tool, But with Two Logical Problems. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3130530 (Accessed 24 September 2025).

- Oxford College of Marketing (2023) Using The Ansoff Matrix to Develop Marketing Strategy. [Blog] Updated October 2023. Available at: https://blog.oxfordcollegeofmarketing.com/2016/08/01/using-ansoff-matrix-develop-marketing-strategy/ (Accessed 24 September 2025).

- The Strategy Institute (2024) The Ansoff Matrix: A Powerful Tool for Business Strategy and Growth. Available at: https://www.thestrategyinstitute.org/insights/the-ansoff-matrix-a-powerful-tool-for-business-strategy-and-growth (Accessed 24 September 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

CollectionsContent relating to: “Ansoff Matrix”

Ansoff Matrix examples created by students to support and inspire your own assignments, plus a free practical guide. Each example demonstrates how to apply Ansoff’s Matrix to effectively analyse strategic growth opportunities, whether it’s market penetration, market development, product development, or diversification. Before exploring these examples, review our practical Ansoff Matrix guide, designed to help you structure and evidence your analysis effectively. For help from a UK-qualified business expert with your Ansoff Matrix assignment, see our business assignment help page.

Related Articles