Sample Undergraduate 2:1 Law Powerpoint

This sample law PowerPoint was written by one of our expert writers, to give you a taste of the work we produce.

-

Slide 1

-

Slide 2

-

Slide 3

-

Slide 4

-

Slide 5

-

Slide 6

-

Slide 7

Slide Notes

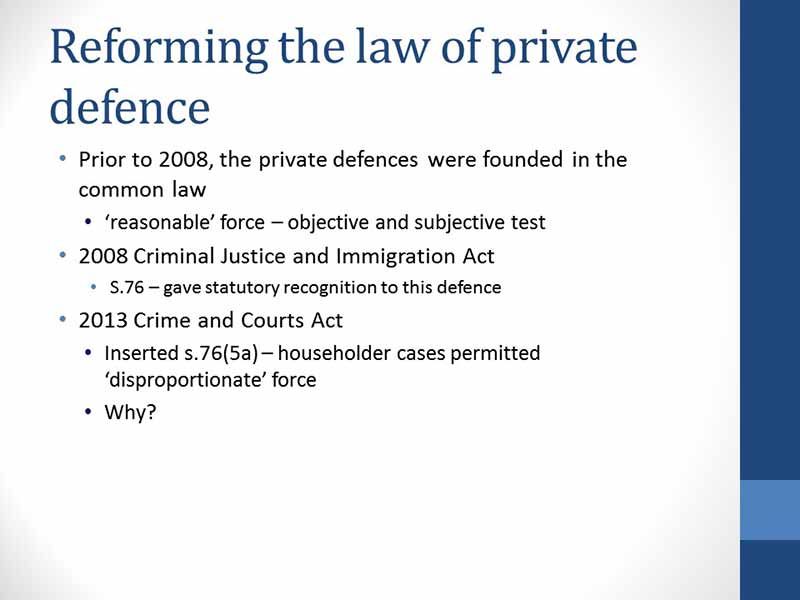

Reforming the law of private defence

- Historically, private defences to crime had authority from the common law, permitting the use of reasonable force in self-defence and in the prevention of crime

- The 2008 Criminal Justice and Immigration Act only sought to acknowledge these defences in the statutory sphere, as emphasized by s.76(9)

- In determining whether a person's use of force was reasonable, the Court considers whether the person's actions were objectively reasonable in the circumstances as they subjectively believed them to be.

- Then, the 2013 Crime and Courts Act, s.43 inserted s.76(5a) regarding householder cases.

- Per s.76(5a), the defence was extended to cover circumstances in which a person's use of force was objectively disproportionate, in the circumstances as they subjectively appreciated them

- Despite that the House of Lords previously declined the opportunity to extend the defence to cover 'excessive force' in R v Clegg (1995), where a soldier shot at a retreating vehicle he believed was in use by terrorists, in fact killing a joyrider.

- What was the impetus for this reform? As will be seen, this law strongly evidences the view that criminalization is frequently a strongly political action, and the response to a 'moral panic'.

Slide Notes

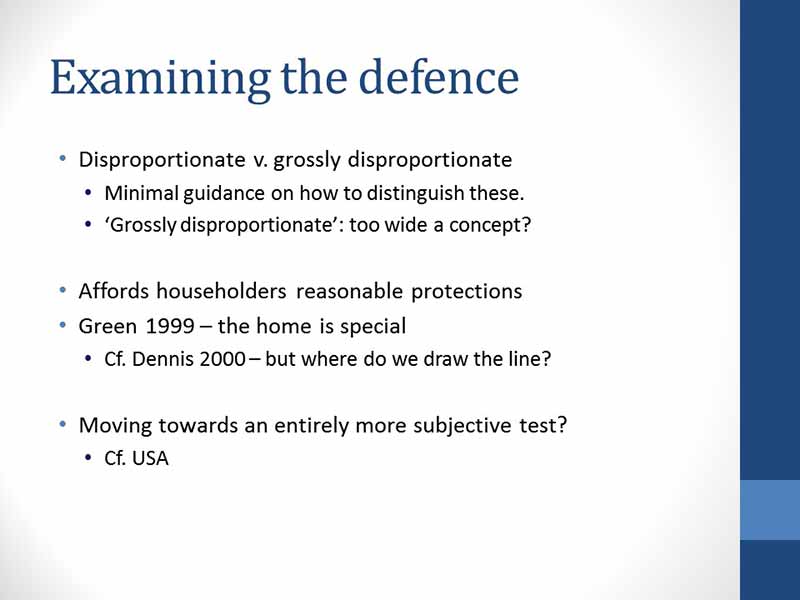

Examining the defence

- The new householder defence is not limitless though; householders are still not permitted to use objectively grossly disproportionate force in managing intruders.

- Yet little guidance has emerged as to distinguishing disproportionate and grossly disproportionate.

- To paraphrase Wolkind QC: I kick a criminal once: reasonable, twice: understandable, three times, forgivable, four times, debateable, five times, disproportionate…, eight times and it's grossly disproportionate. "I don't understand why sentencing should take place in the home".

- Does this give too much discretion to the Courts, at the high cost of legal certainty?

- However, victims should not have to fear criminal sanction if they panic and overact when responding to an intruder

- Green 1999: home cases are special due to the historical, cultural significance of the home as a place of safety,

- Cf. Dennis 2000 asks though, can you then reasonably kill a 10 year old boy stealing apples from your kitchen?

- Thus it seems the test for householders is much closer to a purely subjective test

- Similar to the USA, where reasonable belief in danger is the only requirement for force

- Can be highly controversial - e.g. 'stand your ground' in State of Florida v Zimmerman (2012)

Slide Notes

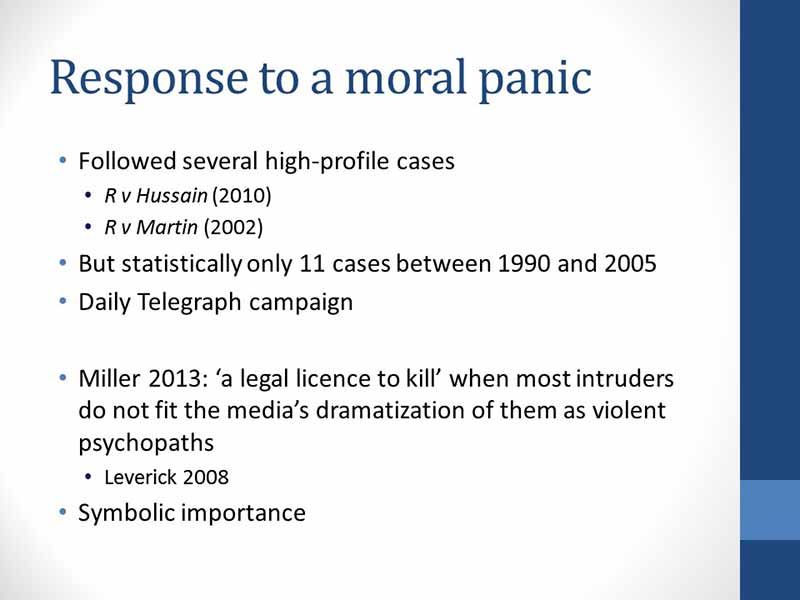

Response to a moral panic.

- Cohen (1972) posits that criminalisation often occurs because of moral panics: widespread fears of something evil fundamentally detrimental to societal values.

- Dobinson & Elliott 2014. The reform was "the product of significant policy-driven lobbying and several high-profile cases".

- R v Hussain (2010) - two men prosecuted for chasing and severely beating a violent burglar in revenge. Public outcry, many called for merciful sentences.

- R v Martin (2002) - a farmer shot indiscriminately at burglars

- highly-publicised

- Yet, per the CPS, only 11 cases between 1990 and 2005 where householders were prosecuted for disproportionate force, including a case where a man waited for a burglar, beat him, tied him up, threw him in a pit and set him on fire.

- Thus was the prior law really failing?

- The Daily Telegraph campaigned to strong popular support - 79% favoured reform

- Miller 2013: "the media [paints].. all invaders of homes as being violent psychopaths". Yet really, s.76(5a) constitutes a legal licence to kill.

- Leverick 2008: most want to escape without any contact from the homeowner

- Fundamentally, s.76(5a) appears to be done for symbolic importance

- Introducing new criminal law is an easy way for politicians to show they are 'doing something'

Slide Notes

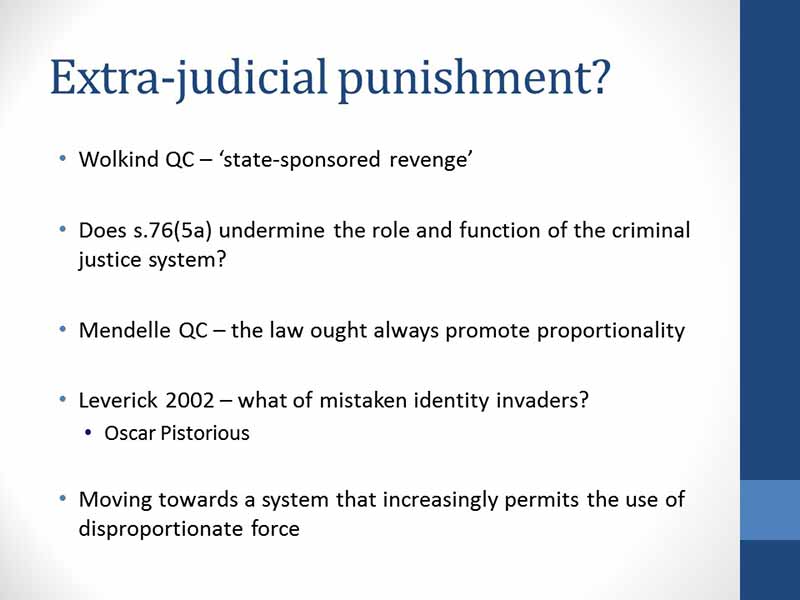

Extra-judicial punishment?

- Some commentators contend s.76(5a) amounts to permitting extra-judicial punishment

- For instance, in R v Hussain (2010), ought it not best for the legal system to determine the appropriate punishment for the burglar, rather than his victims inflicting brain injuries?

- The media painted the legal system as more favourable to the burglar who had intruded Hussain's home and threatened his family, rather than the Hussain brothers, seemingly causing a moral panic

- Wolkind QC contends: encourages vigilantism and 'state-sponsored revenge'

- We ought trust police and prosecutorial discretion

- Not all home defenders are even prosecuted, e.g. Peter Flanagan

- Mendelle QC 2010 : s.76(5a) effectively 'sanctioned extrajudicial execution… for an offence, burglary, that carries a maximum of 14 years".

- Further: "the law should always encourage people to be reasonable… to be proportionate".

- Also, may encourage burglars to carry weapons/use pre-emptive force

- Leverick 2002 questions where one may find justice for an innocent person mistaken as a home invader under such laws

- High-profile South African case of Oscar Pistorious

- Miller 2013 compellingly argues the UK is becoming more extreme and more similar to South African law on self-defence which allows killing in self-defence for protection of property

Slide Notes

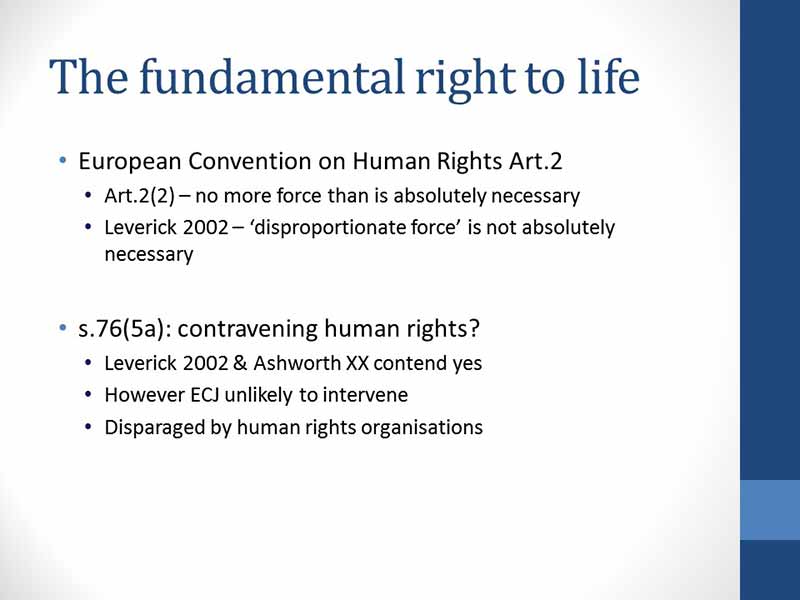

The fundamental right to human life

- Under the European Convention of Human Rights and the 1998 Human Rights Act, every person has an inalienable right to life.

- Per Art.2(2) - no more force than is absolutely necessary may be used which results in the deprivation of life

- Leverick 2002: killing due to mistaken belief without reasonable foundation is not 'absolutely necessary'

- Stewart v UK (1984) - Commission determined Art.2(2) did apply to self-defence

- Subsequently, it can be compellingly argued that s.76(5a) exists in significant juxtaposition to Art.2

- Andronicou (1998) - Cypriot MMAD officers acted, taking measures "which they honestly and reasonably believed were necessary", per European Court.

- Leverick 2002 points out that the Court and Commission have 'consistently held' that self-defence with mistaken belief must be 'for good reasons', per judgments in McCann, Andronicou, Gül, inter alia.

- Academic heavy-weight Ashworth also points to this as proof of English law contravening the ECHR.

- Nonetheless, both academics consider it seems unlikely that the ECHR will assert this view.

- Particularly unlikely in light of 'Brexit'

- Human Rights organisation, 'Liberty' described s.76(5a) as 'grim, head-line chasing at its very worst' in 2013 report for the House of Commons.

Slide Notes

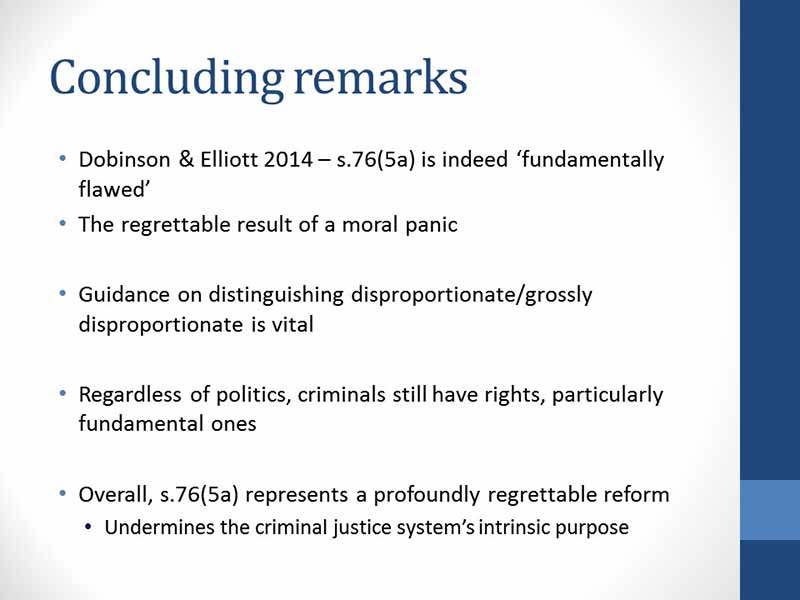

Concluding Remarks

- Dobinson & Elliott 2014 seem correct in their assertion that s.76(5a) is "fundamentally flawed"

- The poorly considered consequence of a media-fuelled moral panic intended to fill a lacuna that did not really exist

- Ashworth makes the measured observation that 'pressure on politicians' means that delays for the sake of 'great and considered responses… may invite criticisms of indecision and procrastination'.

- It remains to be seen where the Courts will draw the line

- On one hand, an area sorely in need of clarification and guidance as to where the line is drawn between disproportionate and grossly disproportionate

- Yet, cases remain very rare, so it may be a long wait and legal certainty suffers in the interim

- Thus the law in this regard has a very uneasy position in relation to human rights

- David Cameron, notoriously commented when 'a burglar steps over your threshold… they leave their human rights outside'.

- Popular support for the notion that the intruder is committing a criminal act and thus is undeserving of protection

- But this is not how the legal system works; even criminals have rights, especially fundamental ones

- S.76(5a) profoundly undermines the purpose of the Criminal Justice System

Get help with Powerpoint law assignments and more - find out about our law assignment help here!