Effects of Residential Schools on Aboriginal People

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Cultural Studies |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3594 words | ✅ Published: 18 May 2020 |

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE

AND THE EFFECTS OF RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS

___

LIFE BEFORE CONTACT

One of the many Aboriginal tribes in Canada are the Haida. The Haida are located on the archipelago of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) in northern British Columbia, Canada. Due to their location by the ocean, the Haida people were seafaring and often ate seafood, such as fish.

Haida Society

The Haida people were organized into communities and settlements, and was separated into two social groups called the Ravens and the Eagles. These two groups were then divided into twenty-two and twenty-three family lines respectively. Historically, Haida villages held various lineages and oftentimes housed both social groups. Marriages that took place during the past had to be with people of the opposite social group and children produced from these marriages would take the same social group as their mothers.

A person’s lineage within Haida society gave them certain rights, privileges, and entitlements. One such entitlement was economic resources such as fishing spots, hunting grounds, or housing sites. “Names were a highly coveted lineage property and were bestowed to mark different stages of people’s lives. Names were also given to important material belongings such as fish traps, houses, canoes, feast dishes and even feast spoons. Face painting and tattoo designs were also lineage property, as were all crests, of which Swanton lists over seventy.” (Canadian Museum of History, “Social Organization”)

Clothes

The Haida often made their clothing out of red or yellow cedar bark. Weather in their area was often warm and thus they needed little clothing. They most often used their clothing to protect them from the weather, mostly rain. This lead to the production of cedar hats, skirts, long capes made from elk skin. Clothing was made by the women for the members of their families while the men were out hunting.

Food

Due to their seafaring nature and close proximity to the ocean, the Haida often hunted and ate fish. They used canoes built from tree trunks to bring men out into the water in order to hunt fish and sea mammals. They also hunted on land as well. The men would go on hunting trips for animals in the area such as deer, and other small game. Women would be the ones to gather food such as berries that could be eaten or turned into paints/dyes for totem poles or clothing.

Motivation Of Residential Schooling

Residential Schools were created by the Canadian government for the purpose of amillilating Aboriginal children. They masked this deeper purpose with the guise of wanting to give aboriginal children a better education, but did not do very well. “I feel certain that this school will be a great success, and that it will be a chief means of civilizing the Indian; but to obtain this result, accommodation must be made to take in more pupils, as now we can only take in but one out of each reserve. A school for Indian girls would be of great importance, and I may say, would be absolutely necessary to effect the civilization of the next generation of Indians[;] if the women were educated it would almost be a guarantee that their children would be educated also and brought up Christians, with no danger of their following the awful existence that many of them ignorantly live now. It will be nearly futile to educate the boys and leave the girls uneducated.” (Dominion of Canada. Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended 31st December, 1885. p. 138. J. Hugonnard, Principal Qu’Appelle Industrial School.)

The first of these schools was opened near Quebec city, by a group called The Récollets in 1620. But it was not apart of Canada at this time and was instead still under the rule of France. This history of assimilation through schooling had been going on a long time, but the first school to be considered part of the Residential School System as defined by the IRSSA, was the Mohawk Indian Residential School which opened in 1831 in Brantford, Ontario. The school was known by students “as the “Mushhole” on account of the poor food or ‘mush’ served there.” (wherearethechildren.ca, “Research”) By the end of the Residential school era, a total of 180 residential schools had opened, with a maximum of 80 being operational at one time (1931).

The church played a large role in the operation and daily life within the residential school system. Although the program was initiated by the government, it was the churches that ran and taught in the schools. This partnership ended in 1969 and the government took full control over the school system.

Life In Residential Schools

Life in residential schools was difficult for many Aboriginal children. Approximately 150,000 First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children between the ages of four and fifteen were forced to attend these school, many of which were ripped from their families and communities by the Canadian government. Governments would put pressure on the parents of Aboriginal children in order to forced them into putting their children into these schools.

Residential Schools were not the same as regular, non-aboriginal schools. For one they were run by the Catholic church, who placed a mandatory and important value on teaching Christianity to the students. Secondly, Aboriginal students who attended residential schools got an average of two to four hours in the classroom compared to the five or more hours that non-aboriginal students received. Time outside of the classroom was used for chores and upkeep of the building in order to keep the system in order.

Classes in residential schools focus on reading, writing, and math. Due to the curriculum and poor teaching standards, students in residential schools rarely surpassed a third grade education level. Teaching staff were not often qualified teachers, but rather missionaries or nuns. This was the reason such an importance was placed on religion.

“Teachings focused primarily on practical skills. Girls were primed for domestic service and taught to do laundry, sew, cook, and clean. Boys were taught carpentry, tinsmithing, and farming. Many students attended class part-time and worked for the school the rest of the time: girls did the housekeeping; boys, general maintenance and agriculture. This work, which was involuntary and unpaid, was presented as practical training for the students, but many of the residential schools could not run without it… Many were discouraged from pursuing further education [after being forced to leave at 18].” (indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca)

Female students also received very little in regards to sexual education. “I didn’t know what was going on because they never told us. All they did was mark the calendar and give you a piece of rag that was already stained, dirty looking, ugh. We had to use that but I didn’t even know what was happening with me.” (Muriel Morrisseau, pressprogress.ca) This caused a sense of shame and embarrassment in regards to female sexual health and a lack of knowledge in things such as contraception or the menstrual cycle.

Abuse Within The School System

Residential schools were not held to that same standards of care that we would have nowadays, or even for non-Aboriginal schools at the same time. Children that attended residential school often suffered for years with physical, physiological, and sexual abuse. These often cruel acts left children scarred and many now suffer from PTSD due to their time in the school system.

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse ranges in severity but all were harsh. Children would often receive beatings or other forms of physical abuse as punishment for even the smallest of offences. Not only were they used for punishment, but as a way to promote assimilation and the abandonment of their native culture. “Students who did not adhere to school schedules and regulations received strappings (whippings) and were often humiliated in front of peers” (https://www.facinghistory.org)

Story #1

“They used to give us shock treatments for bedwetting. A lot of us never wet our beds but we still had to do it anyway. They said it worked for the girls but it didn’t work for the boys. They couldn’t really ever find out why, but I think it was because of the sexual abuse that went on there. . . . They used to bring in a battery—a motor of some sort or some kind of gadget, and he’d put the girl’s hand on it and it would jerk us and it would go all the way through us from end to end—it would travel. And we would do that about three times.”

(Lorna, who was at the Mohawk Institute from 1940 to 1945)

Psychological Abuse

Students were not only ripped away from there families and physically abused, they also experienced many types of psychological abuse. They were taught through Christianity that they vary race deemed them to hell and that they were ‘dirty’. This not only causes emotional turmoil in any person of any age, but it can also cause a deep loss of connection and acceptance. Children find themselves stuck between wanting to achieve heaven, something they were taught is the ultimate goal and gift, but are told time and time again that they are simply not white enough to be given entry. This was only the beginning of the emotional and psychological abuse and trauma that went on under the supervision of the residential school system.

Children were forced to witness violence, and abuse daily. There are hundreds of stories about the traumatic events that students were forced to witness while attending these schools that have left their mark and still effect these individuals to this day. Some were more temporary in nature (shaving of a girls head) but others were much more impactful and scarring.

Story #2

“I remember the one young fellow that hung himself in the gym, and they brought us in there and showed… showed us, as kids, and they just left him hanging there, and, like, what was that supposed to teach us? I’m 55 years old and I still remember that.”

(Antonette White)

Story #3

“Punishment for running away varied. One boy was hauled up in front of all the assembled students by the principal. He had a reputation for being mean. He forced the boy to pull his pants down and gave the boy 10–15 straps with a great big leather strap. Girls often had their head shaved bald if they tried to run away so that everyone would know. It was awful. I felt very ashamed…”

(Geraldine Sanderson)

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse was also common in the residential school system. As the schools were often times under regulated, abuse of any nature, even sexual, often went undiscovered and undealt with. Sexual abuse was not only an issue for female students, but the male students as well. “All told, the figures suggest that at least one of every five students suffered sexual abuse at the schools.” (https://www.theglobeandmail.com) This left many students suffering from PTSD and promoted the cycle of abuse that would last for generation to come.

Story #4

“They were there to discipline you, teach you, beat you, rape you, molest you, but I never got an education. I knew how to run. I knew how to manipulate. Once I knew that I could get money for touching, and this may sound bad, but once I knew that I could touch a man’s penis for candy, that set the pace for when I was a teenager and I could pull tricks as a prostitute. That’s what the residential school taught me. It taught me how to lie, how to manipulate, how to exchange sexual favours for cash, meals, whatever the case may be.”

(Elaine Durocher, on how she learned the tools for a life in the sex trade at residential school)

Death

Death in residential schools was not uncommon as well. “In 1907, government medical inspector P.H. Bryce reported that 24 percent of previously healthy Aboriginal children across Canada were dying in residential schools.5 This figure does not include children who died at home, where they were frequently sent when critically ill. Bryce reported that anywhere from 47 percent (on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta) to 75 percent (from File Hills Boarding School in Saskatchewan) of students discharged from residential schools died shortly after returning home.6” (indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca)

The abuse and death within and caused by residential schools did not go completely unnoticed by those inspecting the schools or those running them. The government was not in the dark over this topic either. Many knew of the trauma being inflicted on aboriginal children within school walls and yet did little to protect them. “The extent to which Department of Indian Affairs and church officials knew of these abuses has been debated. However, the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples and Dr John Milloy, among others, concluded that church and state officials were fully aware of the abuses and tragedies at the schools…. The Department of Indian Affairs would promise to improve the schools, but the deplorable conditions persisted.9” (indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca)

Lasting Effects

Residential schools left there marks on the thousands of students that attended them, and these effects can still be felt in their communities today. Aboriginal communities suffer greatly under the burden of substance abuse, addiction, victimization, and unemployment. All of the following, also contribute to an extremely high rate of suicide and suicide attempts in both Aboriginal youth and adults. These issues grow with every generation and will only continue to do so until they begin to be treated at the root cause rather than on an individual bases.

Suicide

Suicide and suicidal thought rates amongst aboriginal youth are much higher than that of their non-aboriginal peers. One in four aboriginal people report having a suicidal thought in their lifetime; one in ten in the last year. This has been going on for decades.

“…In the 1994-to-1998 period, the suicide rate among children and youth in… Inuit Nunangat… was 18 to 25 higher than in the rest of Canada.” (Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2012; Past-year suicidal thoughts among off-reserve First Nations, Métis and Inuit adults aged 18 to 25: Prevalence and associated characteristics, Mohan B. Kumar and Amy Nahwegahbow)

Suicide and suicidal thoughts are not caused by only one event or reason, but are instead caused by a collection of various factors such as genetics, social factors, family characteristics, childhood experiences, and so much more. Smoking and alcohol abuse often go hand in hand with depression and suicide, all three of which are current effects of intergenerational trauma.

Some studies have narrowed down some of the risk factors for certain communities. These factors are believed to raise the likelihood of someone, mainly youth, attempting or committing suicide. For example the following are risk factors for Inuit youth:

– Being male

– Having a friend or family member who attempted or committed suicide

– History of abuse (physical or sexual)

– Parental alcohol or drug issues.

Many other factors such as time spent at a residential school, drug or alcohol dependence, high levels of stress, and various mood disorders also increase suicide risks.

Smoking, Alcohol, and Drugs

Smoking

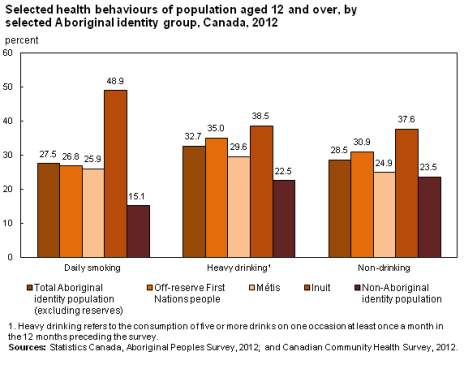

Although not the worst thing you can smoke, cigarettes are in no way good for your health. Rates of smoking (regular and occasional) are higher by thirty-four point six percent for First Nations living on reserves across Canada. Of those who do smoke, the majority do so daily. The majority of on reserve, Aboriginal smokes are in the age range of eighteen to twenty-nine (53.9%).

Alcohol

Long-term alcohol abuse can cause a multitude of problems within the human body such as: high blood pressure, cardiomyopathy, damage to the heart, alcoholic hepatitis, fibrosis, an increases risk of various cancers, pancreatitis, a weakened immune system and overall liver damage. Alcohol is also known for working alongside depression.

“According to a study published in Addiction, individuals dealing with alcohol use disorder or depression are at double the risk of developing the other condition. This was not simply a correlation, as the study concluded that alcohol use disorders and depression have a causal relationship.” (‘Can Alcohol Induce Depression?’, American Addictions Center)

Alcohol is sometimes used as a way for certain people to deal with their depression, wanting to escape or dull their feelings of overwhelming sadness or loss of hope. This effect is only temporary and alcohol has only been shown to worsen depression over time. As the individual becomes more dependant on alcohol, they will see many negative effects on the other parts of their lives such as work, social connections, and finances. It is for these reasons that alcoholism is such an important problem to tackle, especially in communities that have high rates of alcohol abuse.

Aboriginal people have higher rates of alcoholism and alcohol abuse than other ethnicities. This issue can be traced back to many of the same causes of suicide. Poor living conditions, social racism, histories of abuse, and unemployment can all be causes that may drive someone to alcohol abuse. These are all also highly present in Aboriginal people, both on and off of the reserve.

Drugs

Just the same as alcohol abuse, drug abuse effects all aspects of the users life. Many individuals suffering with drug abuse end up losing many social connections and even their jobs. Aboriginal communities have high rates of drug abuse due to many of the same factors in suicide and alcoholism. Drug abuse in Aboriginal communities is more prevalent in more northern and remote locations, which may be caused by a lack of access to rehabilitation and drug abuse programs. A survey from 2008 to 2010 had Aboriginal communities across Canada rating alcohol and drug abuse as one of their top three problems, along with housing and unemployment.

Victimization

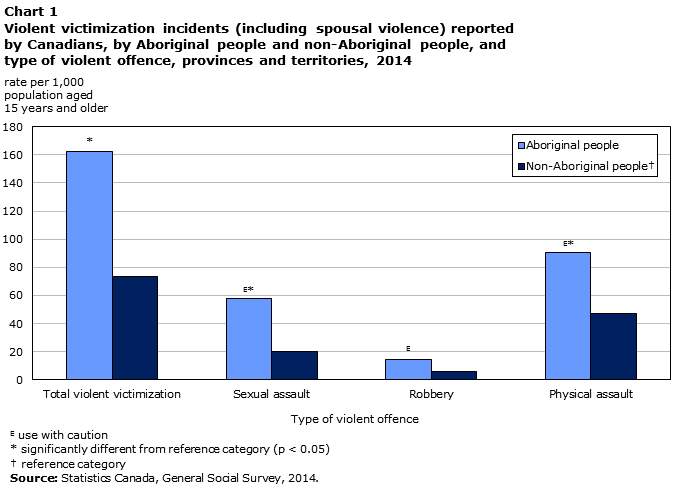

Aboriginal peoples are at a higher risk to becoming the victims of crime both on and off the reserve; Aboriginal women even more so when other factors such as gang affiliation are taken into account. Twenty-eight percent of Aboriginal people have reported that they or their household have been the victim of crime in the last year, and the overall rate of violence against Aboriginal people is almost double that of violence to non-aboriginal people. This is a cause for concern.

“Regardless of the type of offence, rates of victimization… were almost always higher for Aboriginal people than non-Aboriginal people… The sexual assault rate for Aboriginal people was almost three times that of non-Aboriginal people , while Aboriginal peoples’ rate of physical assault was close to double that of non-Aboriginal people.” (Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014, Jillian Boyce)

This rate is affected by many factors such as drug and alcohol abuse, history of abuse, childhood maltreatment, history of homelessness, and poor mental health. When taking these factors into account, statistics showed that Aboriginal descent did not have a direct correlation to higher victimization, except in females.

Aboriginal women were twice as likely to be the victims of crime than their male counterparts. This rate raised even more for females between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four, almost triple that of their non-aboriginal peers.

Conclusion

Residential School are a large part of Canada’s dark history. The Canadian government, along with the Catholic churches, traumatized and killed thousands of aboriginal children across the country over many years, and the effects of those actions can still be felt today through mental health, addiction, substance abuse, and victimization. Much is needed to heal the damage done to the Aboriginal communities of Canada and one of the first steps in that process is understanding and teaching the newer generation, both aboriginal and non-aboriginal, what happened and why it should never happen again. Through knowledge and understanding we will promote acceptance, which will only serve to aid the Aboriginal communities of Canada in finding access to support in their efforts to heal.

Bibliography

- https://www.warpaths2peacepipes.com/indian-tribes/haida-tribe.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haida_people

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/haida/hapso01e.shtml

- http://www.bigorrin.org/haida_kids.htm

- http://pressprogress.ca/14_first_hand_stories_underlining_how_residential_schools_tried_to_get_rid_of_indigenous_cultures/

- http://rschools.nan.on.ca/upload/documents/section-3/a-typcial-day-at-residential-school.pdf

- https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_residential_school_system/

- http://wherearethechildren.ca/en/timeline/research/

- https://www.facinghistory.org/stolen-lives-indigenous-peoples-canada-and-indian-residential-schools/chapter-4/punishment-and-abuse

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/one-in-five-students-suffered-sexual-abuse-at-residential-schools-figures-indicate/article20440061/

- https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/reports-publications/aboriginal-health-research/statistical-profile-health-first-nations-canada-determinants-health-1999-2003-health-canada-2009.html

- http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-656-x/89-656-x2015001-eng.htm

- https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-653-x/89-653-x2016008-eng.htm

- https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/alcohols-effects-body

- https://americanaddictioncenters.org/alcoholism-treatment/depression/

- http://www.ccdus.ca/Eng/topics/First-Nations-Inuit-and-Metis/Pages/default.aspx

- https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/ap-pa/ap-pa-eng.htm

- https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/health-promotion/mental-health-wellness/first-nations-inuit-hope-for-wellness-help-line.html

- http://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/mental-health-and-wellness-services-for-indigenous-children-and

- -youth/

- https://www.nativechild.org/

- http://www.onwa.ca/programs

- http://www.onwa.ca/avfl

- http://www.onwa.ca/asaw

- https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/reports-publications/substance-use-treatment-addictions/alcohol-drugs-solvents/national-youth-solvent-abuse-program.html

- https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/reports-publications/substance-use-treatment-addictions/alcohol-drugs-solvents/national-native-alcohol-drug-abuse-program.html

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal