Schön’s reflective model: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action guide

Info: 1581 words (6 pages) Study Guides

Published: 10 Sep 2025

Stuck on your management assignment? Don’t just reflect – act! Get an MBA-qualified writer to help with Schön’s reflection-in-action or any other management assignment. See our management assignment help page for info.

Reflection is a cornerstone of effective management learning. As the educational philosopher John Dewey famously noted, “We do not learn from experience… we learn from reflecting on experience” (Dewey, 1933).

In management education, scholars regard reflective practice as an essential skill for developing thoughtful and adaptable leaders (Hibbert, 2012; Mintzberg, 2004). Structured reflection helps bridge the gap between theory and practice (Mezirow, 1991). It also builds self-awareness in managers.

Indeed, many MBA programmes and professional courses now incorporate reflective journals and personal development plans. These activities emphasise that learning from your own experience is just as important as formal academic knowledge (QAA, 2009; Ronnie, 2016).

Effective reflection enables future managers to critically examine their decisions and behaviours. It allows them to continuously improve and respond to complex business challenges.

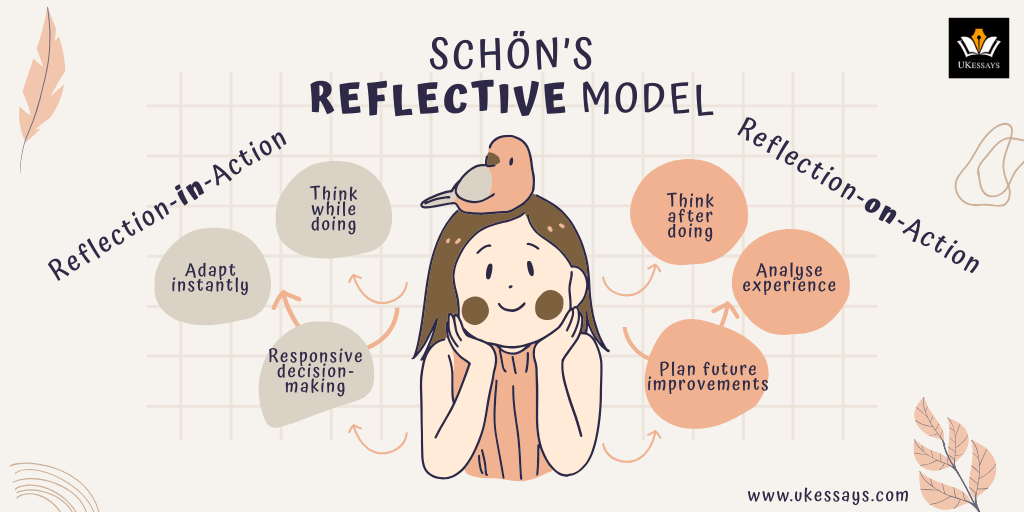

Reflection-in-action: thinking and adapting in the moment

Donald Schön introduced the concept of reflection-in-action to describe how practitioners think on their feet and make immediate adjustments during an activity (Schön, 1983). In simple terms, Schon’s reflective model is about reflection in real time.

The practitioner becomes, in Schön’s words, “a researcher in the practice context,” not separating thought from action as they experiment with solutions in the moment (Schön, 1983). For example, a manager might notice during a tense team meeting that the usual approach is failing. As a result, she pauses to rethink and alter her facilitation style on the spot.

This on-the-fly reasoning is reflection-in-action. It is the ability to immediately interpret what is happening, consider different responses, and implement a change right then and there.

Such real-time adaptability is crucial in leadership situations. It allows professionals to address issues as they arise, rather than waiting until later. It requires presence of mind and often draws on tacit knowledge and experience.

By reflecting in action, managers can test adjustments and observe outcomes instantly. By doing this, they are learning and improving even as they perform their duties (Bolton, 2014).

Reflection-on-action: looking back to evaluate and improve

In contrast, reflection-on-action refers to the retrospective process of thinking about an experience after it has happened (Schön, 1983). This is the more familiar form of reflection: examining past events to draw lessons and improve future practice.

After a significant project or decision, an effective manager will step back and deliberately analyse what occurred. They explore questions such as:

- What happened and why?

- What outcomes were achieved versus intended?

- What went well, and what could have been handled differently?

Systematically reviewing the event gives the practitioner deeper insight into their own actions and the team’s dynamics.

Reflection-on-action often takes place through writing (for instance, in a learning journal or an after-action review report). Writing things down encourages careful thought about your experiences.

The key goal is to transform experience into learning. By looking back on a situation, managers can identify successes and mistakes, understand what factors contributed to those outcomes, and then plan changes to their approach in the future.

This deliberate hindsight reflection strengthens your professional growth. It turns every major experience – whether a triumph or a failure – into a source of actionable knowledge for improvement (Moon, 2004).

Examples of reflection-in-action and on-action

To illustrate the difference between these two modes, consider the following examples from a management context:

Reflection-in-action example:

During a project meeting, a conflict suddenly arises between team members. In the heat of that moment, the project manager recognises the discussion is derailing. In response, she immediately adjusts her facilitation style.

For example, she might rephrase the problem, introduce a quick team exercise, or diplomatically address the tension to steer the group back on track. Her swift adaptation demonstrates reflection-in-action. She is reflecting and acting simultaneously to manage the conflict.

Reflection-on-action example:

After an operations change initiative has been completed, the manager schedules a debrief to review the outcomes. He carefully evaluates how the initiative unfolded and why certain challenges emerged.

He might realise afterwards that communication was insufficient at the start of the project, so misunderstandings occurred.

Writing in his reflective journal, he notes that “On reflection, the rollout plan lacked early stakeholder input, and I would involve key staff more in future changes.”

This thoughtful hindsight analysis is reflection-on-action. The manager is dissecting the completed project to learn lessons. He acknowledges what worked or failed so that he can improve next time.

Applying Schön’s reflective model in assignments

Management students often complete reflective writing assignments – for example, personal development plans (PDPs), learning journals or leadership essays – to demonstrate how they learn from experience. Schön’s framework of reflection-in-action and on-action can provide a useful structure for such assignments.

In practice, most academic reflections will be written after an event (making them primarily reflection-on-action). However, you can still incorporate reflection-in-action by describing any moments during the experience when you had to adjust your approach.

For instance, in a leadership essay you might recount how you changed your strategy midway through a team task. That immediate adjustment was an example of reflection-in-action. Later, you would analyse that decision after the task was over – demonstrating reflection-on-action.

Organising your reflective account in this dual way shows a sophisticated understanding. It indicates you can identify immediate, in-the-moment learning as well as broader lessons gained after the fact.

When structuring a reflective journal or PDP, consider writing in a narrative sequence. Describe what happened, what you did in the moment, and what you learned afterward.

Additionally, be explicit about how theory connects to your experience. Using Schön’s terms, you can even label parts of your assignment to signal when you were reflecting in action versus reflecting on action.

For example, you might write “In the moment, I realised…” to denote reflection-in-action, or “After the event, I realised…” to indicate reflection-on-action. This approach makes the structure clear and shows that you understand both dimensions of reflection.

Tips for deeper reflective writing

To move your reflective writing beyond simple description, you need to engage in critical reflection.

One key strategy is to integrate relevant management theories or models into your analysis (Moon, 2004). For example, if you are reflecting on a team conflict you experienced, you might relate it to leadership style theories or a conflict resolution model.

Consider whether you practised a democratic leadership approach, or whether an autocratic style contributed to the tension. By linking concrete experiences with abstract concepts, you demonstrate deeper insight.

Consider multiple perspectives in your reflection. Ask yourself not only how you felt, but also how others might have perceived the situation and why things unfolded as they did. This helps you avoid a narrow, purely personal narrative and instead achieve a more balanced, analytical view.

Also, pose probing questions throughout your reflective writing (e.g. “Why did I react that way under pressure? What assumptions was I making?”) and then attempt to answer them.

Acknowledge both strengths and weaknesses in your performance rather than just narrating events.

- If something went well, explore why it succeeded and how you might replicate it.

- If something went poorly, do not just recount it. Instead, dig into the causes and explain what you would change next time.

Using evidence or theory to support your interpretations adds credibility and depth. For instance, you might refer to a change management framework to explain a failed initiative.

Sample sentence starters for reflection

Getting started with writing in a reflective tone can be challenging. Here are some sentence starters that indicate reflective thinking, divided into in-action and on-action contexts:

Reflection-in-action starters:

- “In the moment, I recognised…”

- “At the time, I noticed…”

- “While X was happening, I decided…”.

Reflection-on-action starters:

- “On reflection afterwards, I realised…”

- “Looking back, I now understand…”

- “After the event, I felt that…”.

These phrases signal to the reader whether you are discussing something you noticed during the experience or an insight you gained afterwards. Using such language can make your reflective writing clearer and more intentionally structured.

Finally, remember that good reflection is honest and thoughtful. It not only describes events, but also delves into your reasoning, emotions, and plans for improvement. By applying Schön’s reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action model, management students can produce reflective accounts that demonstrate meaningful learning. This practice supports their ongoing development as future leaders.

Stuck on your management assignment? Don’t just reflect – act! Get an MBA-qualified writer to help with Schön’s reflection-in-action or any other management assignment. See our management assignment help page for info.

References and further reading:

Bolton, G. (2014) Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development (4th edn). London: SAGE.

Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: D.C. Heath.

Hibbert, P. (2012) ‘Approaching reflexivity through reflection: Issues for critical management education’, Journal of Management Education, 37(6), 803–827.

Mezirow, J. (1991) Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mintzberg, H. (2004) Managers Not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Moon, J. A. (2004) A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) (2009) Personal Development Planning: Guidance for Institutional Policy and Practice in Higher Education. Gloucester: QAA.

Ronnie, L. (2016) ‘Reflection as a strategy to improve management practice: insights from management education’, Acta Commercii, 16(1), a392. DOI: 10.4102/ac.v16i1.392.

Schön, D. A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: