Preparing for your PhD viva voce: typical questions and strategies for success

Info: 10461 words (42 pages) Study Guides

Published: 15 Dec 2025

Our PhD-qualified team provides PhD help across every stage of your doctorate, including proposal writing services, dissertation writing help, support with individual chapters, full PhD thesis writing services, editing, examiner-style feedback, and viva voce preparation. Find out more on our PhD help page or contact our team to discuss how we can support you.

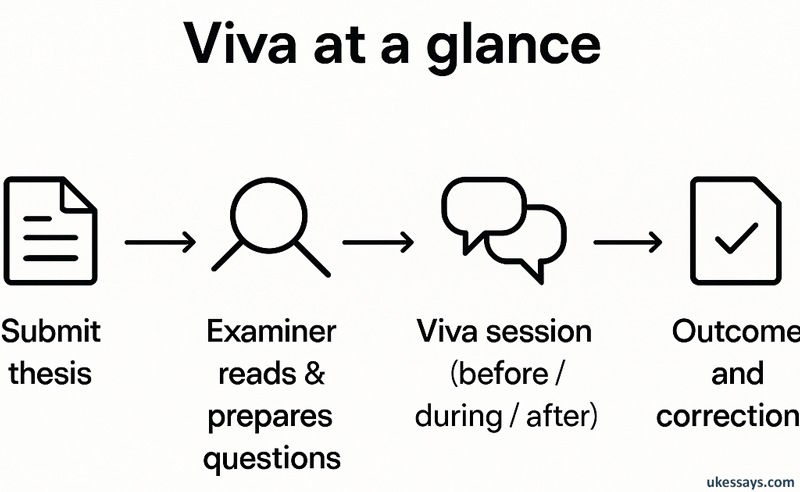

The viva voce (oral examination) is the final hurdle of a doctorate – an opportunity to discuss and defend your thesis with examiners – after which you may be asked to complete corrections before the degree is awarded. It can be daunting, but with the right preparation you can approach it with confidence.

This guide explains what to expect from the viva, how to prepare effectively, and how to handle typical questions with practical, evidence-based strategies.

Understanding the PhD viva examination

A PhD viva is an oral examination where you showcase your knowledge and defend your research in front of a small panel of examiners. It is normally a closed-door discussion focused on your thesis.

Examiners will have read your thesis in detail, and the viva allows them to verify that the work is genuinely yours, probe your understanding, and ensure the research meets the standard for a doctorate.

A viva typically aims to

- authenticate the thesis as your own work,

- place your research in the broader scholarly context,

- clarify any unclear aspects,

- discuss and develop ideas arising from the research,

- have you justify and defend your methodological and theoretical choices; and

- assess your ability to reflect critically on your work (Tinkler and Jackson, 2004).

In other words, the viva is not an “interrogation” to trip you up, but a scholarly dialogue to confirm that you understand what you did and why it matters.

The format of vivas can vary. In some cases (and some disciplines), you might be asked to give a short presentation of your research at the start, but in many UK institutions you begin straight in conversation with the examiners. In the UK, the examining team usually includes at least one external examiner and often one internal examiner; some institutions also appoint an independent chair, and supervisor attendance (as a non-examining observer) varies by university. (See here for a discussion of the viva voce in other countries). Your supervisor might attend as a silent observer, but often they are not allowed to speak.

A viva usually lasts 1 to 4 hours, though it can be shorter or longer depending on the examiners and how the discussion flows. Examiners often start with relatively easy questions (to help you settle in) before moving to deeper, more challenging ones in the middle, and then finish with broader or lighter questions toward the end (Chow, 2016). This means the conversation might range from simple clarifications (“What do you mean by X term?”) to big-picture debates about your findings or theory, and then wind down to reflective questions (“What was the most interesting thing you found?”). Understanding this typical trajectory can help you mentally prepare for the different kinds of questions coming your way.

Importantly, serious problems at the viva are rare – by the time you’ve reached this stage, your thesis has been deemed worthy of examination. In the UK, outright failure at viva is very uncommon (only on the order of a few percent of candidates), with the vast majority of students who make it to viva ultimately passing – often after making some corrections (DiscoverPhDs, n.d.). UK-wide official pass/fail statistics aren’t published in a single definitive source, but one large study of 26,076 candidates across 14 UK universities (2006–2017) estimated that about 96% of those who reach the viva pass it, with around 4% failing at the viva stage. Knowing this can reassure you that the examiners are not there to “fail” you; they are generally invested in seeing a capable researcher defend work that they have already found acceptable.

The examiners’ role is to ensure the thesis meets academic standards and to give you a chance to demonstrate your expertise and clarify anything necessary. They will be probing and critical – that’s their job – but they are also looking for reasons to pass you, not to fail you. Keep in mind that a challenging question is often a sign that your examiners find your topic interesting and worth discussing in depth. With that perspective, you can approach the viva as an opportunity to talk about your research with fellow experts, rather than as a personal attack (Chow, 2016).

Preparing effectively for the viva

Preparation is key to viva success. You cannot predict every question, but you can ensure you know your work inside out and practise how to articulate your answers. Here are some practical steps to get ready:

Re-read your thesis thoroughly:

In the period between submitting your thesis and the viva, read your thesis again from cover to cover. Pay special attention to any sections you feel less confident about.

It helps to read actively – add sticky notes or highlights to mark key points, important definitions, or potential weaknesses you think examiners might notice.

By the day of the viva, you should be intimately familiar with the content, including the finer details of your methods and the rationale behind every major decision (Tinkler and Jackson, 2004). Examiners will expect you to know what you’ve written, even if it’s been months since submission.

Anticipate questions and prepare responses:

A very useful exercise is to predict possible questions and practise answering them (Roberts, 2004). Go chapter by chapter: for each part of your thesis, ask yourself what an examiner might query. See our examples of common questions below.

Common areas include your choice of research question, theoretical framework, methodology, data analysis approach, and conclusions. Write a list of tough or “feared” questions – the ones you dread being asked – and then draft or outline how you would answer each.

For instance, if your research involved a case study focused on Qatar, examiners might query why you chose a single-country context rather than adopting a broader comparative approach – be prepared to justify your methodological choice clearly. Preparing these answers in advance will make you more confident during the actual viva (Roberts, 2004).

Practice speaking your answers out loud:

It is one thing to know the content in your head, but you also need to convey it coherently in speech. Many students find it helpful to do one or more mock vivas – a practice viva with your supervisor or colleagues who can pose as examiners (Burton and Steane, 2004). A mock viva helps simulate the pressure of answering on the spot and can highlight areas where your answers are unclear or rambling.

Even informal practice with a friend or fellow student, where you take turns asking each other random viva-style questions, is valuable. The key is to get used to articulating your ideas fluently and confidently.

Practise summarising your thesis succinctly, explaining your methods, justifying key choices, and defending your conclusions. If you notice yourself struggling to explain something clearly, that’s a sign you should refine that explanation. As one academic notes, practising out loud (even via video-call with a peer) helps you “get used to hearing your own voice” discussing your research and allows you to polish how you verbalise complex concepts that until now have only lived in your writing (Scoles, 2021).

Know your examiners (if possible):

In many cases you will know in advance who your external (and sometimes internal) examiner is. Research their work and background. Often, the external examiner is a subject expert in your specific field (Delamont et al., 2004). By reading a few of their recent papers, you can get a sense of their approach and any theoretical leanings or viewpoints they might bring. This can help you anticipate particular lines of questioning.

For example, if your external examiner has written extensively from a social constructivist perspective and you positioned your work in social constructionism, be prepared to explain that distinction and why your chosen framework is appropriate.

Knowing the examiner’s interests might also help you prepare some friendly questions to ask them (for instance, asking their view on how your work relates to something they published – it shows engagement with their scholarship). However, don’t panic if you discover an examiner’s work late – the goal isn’t to become an expert in their oeuvre, just to be aware of perspectives they might value or critical points they might raise (Delamont et al., 2004).

Prepare concise summaries and possible aids:

It can be helpful to condense each chapter or theme of your thesis into a brief summary or a diagram for your own reference. Some candidates use mind maps or one-page summaries of each chapter, highlighting the key points, to jog their memory (Scoles, 2021). For instance, you might create a mind-map linking your research questions to your theoretical framework, methods, and main findings. This process of distilling your thesis can clarify the “red thread” or overarching argument of your work.

You are usually allowed to bring a copy of your thesis and notes into the viva. Organise these materials so you can quickly find important sections if needed. Use tabs or sticky notes to mark critical parts (e.g. key literature, your figures, or that equation or transcript excerpt you’re sure will come up). Keep your notes minimal and well-ordered – they are just there for quick reference if your mind goes blank, not to read from verbatim. One candidate who survived her viva suggested that simplifying the notes you bring (for example, using colourful A4 mind-map sheets laid out in front of you) can be more helpful than having a huge stack of papers, which can be overwhelming (Scoles, 2021).

Stay updated and review corrections:

In the time between thesis submission and viva, make sure you stay up-to-date with any developments in your field that might have emerged. Examiners sometimes ask whether you are aware of very recent research related to your topic. A quick literature scan for papers published since you submitted can be wise, so you won’t be caught off guard by “Have you read the latest study by X (2025) which also deals with this issue?”

If you find something significant, you could mention it in passing to show you are aware of ongoing developments. Also, review any minor errors or typos you spotted after submission; if an examiner points one out, it looks better if you can acknowledge it and already have a correction in mind. It demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail.

Mental preparation:

Finally, prepare yourself mentally. The viva is as much a psychological challenge as an intellectual one. Build your confidence by reminding yourself that no one knows your research better than you do.

Plan some strategies for managing stress on the day: get a good night’s sleep, eat something beforehand for energy, and perhaps do a short breathing exercise or whatever helps you stay calm and focused. Remember that nerves are normal – even experienced academics feel a bit anxious before an important presentation – but preparation will help keep them in check.

Go in with a positive mindset: treat the viva as a chance to have an in-depth conversation about a subject you have spent years becoming an expert in. How often do you get two hours of undivided attention from people who have read your work so closely? That can be an exciting (if intense) opportunity.

By following these preparation steps, you will equip yourself to handle the viva. Now let’s look at typical questions examiners tend to ask and how you can approach answering them.

Common viva questions and how to handle them

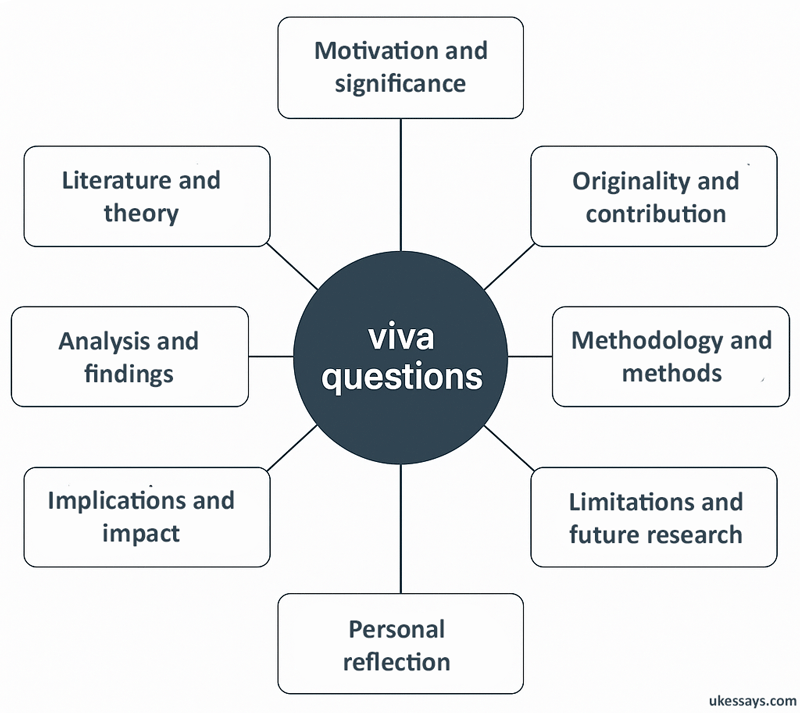

Every viva is unique, but examiners often cover similar ground in their questioning. They will probe various aspects of your research, from the big-picture rationale down to specific methodological choices.

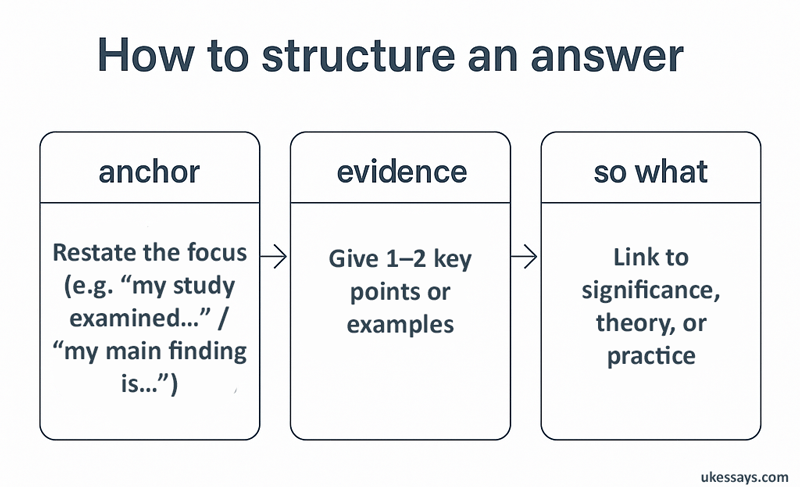

Below, we outline some common categories of viva questions and offer guidance on how to answer effectively. The key to all answers is to be clear, confident, and concise, while demonstrating the depth of your understanding. Answer the question that was actually asked, and then stop – don’t ramble on unnecessarily (Thomas and Brubaker, 2000). If the examiner wants more detail, they will ask.

Keep in mind that it’s perfectly fine to take a moment to gather your thoughts after a question is asked; you do not need to rush into an answer. You can even say, “Let me think about that for a moment,” if needed. Now, onto the typical questions:

Opening questions and research motivation

Examiners commonly begin with broad, gentle questions to break the ice. For example, you might be asked: “Tell us about your research – what is it about, and what is the main argument of your thesis?” or “What inspired you to pursue this topic?” These opening questions give you a chance to set the scene and show your enthusiasm for your work.

How to answer:

Start with a concise summary or elevator pitch for your study. Focus on the core idea or argument that “binds your thesis together.” One approach is to briefly state your research question or objective and why it matters. For instance:

“In a nutshell, my research investigates [X] in order to understand [Y]. The central argument I make is that [Z].”

Aim to highlight the problem or gap that prompted your study and your key finding or thesis claim. You should also be ready to explain why you chose this topic. Perhaps it was sparked by an observed issue in practice, a gap in the literature, or even a personal motivation. A good answer might connect personal and academic reasons: e.g.,

“I have a background in urban planning, and I noticed repeated tensions between residents and local authorities around new housing developments. When I reviewed the literature, I found that most studies focused on large metropolitan areas, with far less attention paid to smaller post-industrial towns. That gap in the evidence base led me to frame the research questions for this thesis.”

This shows both your personal drive and the scholarly rationale.

Crucially, when discussing motivation, convey passion and justification. Examiners like to see that you care about your research, but they also want to know that it addresses a meaningful question. Explain why your work is important in your field (we will elaborate on significance next). Keep your tone confident but not boastful. Even an ice-breaker question deserves a structured answer – avoid going off on tangents about your life story.

Practice summarising your thesis in 2 or 3 sentences and also in a slightly longer form (2 minutes), as you might use one or both in these opening moments. If asked to summarise in one sentence (a challenge some examiners like to pose), focus on your thesis statement – for example:

“My thesis can be summed up as the first systematic examination of [X] which shows that [key result], contradicting the conventional assumption that [Y].”

Being able to distil your work like this is a great skill and reassures the panel that you have a firm grasp of your own research narrative.

Research significance and context

Following on from motivation, examiners often ask something like: “Why is this research important? What is the significance of your study, and who would be interested in these findings?” In the case of a context-specific study, they might ask, “Why focus on this context, and do you think the insights are more widely applicable?” Essentially, they want to know the “so what?” of your research.

How to answer:

This is your chance to articulate the value and relevance of your work. Frame your answer in terms of contribution to knowledge (which we’ll discuss more under originality) and/or practical significance. You might say, for instance:

“Investigating how residents use public green spaces in post-industrial cities matters because everyday use patterns directly shape decisions about urban design, public health initiatives, and local investment. These cities present distinctive conditions – for example, histories of heavy industry, changing demographics, and uneven access to amenities – that previous studies have only partially examined. My research addresses this gap by focusing on one such city in depth, providing insights that can inform urban planning, community programmes, and policy decisions in similar urban environments.”

In other words, highlight both the theoretical significance (e.g. filling a gap in the literature, challenging an assumption, or extending a model to a new context) and any practical implications (e.g. informing policy, improving practice, benefiting a certain group).

Examiners will be pleased to hear you articulate how your findings matter in the big picture. Be specific if possible: instead of generic statements like “This is important for education,” pinpoint which aspects of education and why. For example,

“My findings on patterns of green-space use could help shape local planning and public health initiatives: if we know which communities are under-served, or which groups feel excluded from existing spaces, interventions can be designed to improve access, safety, and engagement.“

If your thesis identified a problem (say, a misalignment between teachers’ beliefs and new curriculum demands), mention how addressing that problem could lead to improvements.

Also, be prepared to place your work in the broader research context. This means situating it in relation to wider debates or comparable settings. Maybe similar studies have been done in other cities or regions – you can explain how your case differs and what distinctive insight it adds. If your examiners ask about generalisability beyond your immediate context, answer honestly about what can and cannot be extrapolated. For example:

“The study is context-specific, but it raises issues – such as how socioeconomic inequality shapes access to public space – that are likely to resonate in many other post-industrial cities. My aim was not to generalise universally, but to deepen understanding of this particular urban context and highlight factors that policymakers and practitioners elsewhere might want to consider in their own settings.”

This shows you understand the scope and limits of your work.

Above all, convey enthusiasm for the significance of your research without sounding overblown. Avoid grandiose claims (“This completely revolutionises language education”) unless they are genuinely justified. It’s safer to confidently state what your research contributes and why that contribution matters, based on evidence, rather than to claim it is ground-breaking in a vague way.

Ground your statements of importance in the actual findings or needs your work addresses. If you have any supporting citations (for example, if policy documents or prior studies emphasise the need for research in your area), you can briefly mention them to reinforce why your research was needed, for example:

“Previous studies (e.g., Smith, 2018; Ahmed, 2019) highlighted a lack of empirical work on how residents use small urban green spaces in post-industrial cities, which my study begins to address.”

This demonstrates that you know the scholarly landscape and where your work fits in.

Originality and contribution to knowledge

One of the core questions in any PhD viva will be some variant of: “What is original about your thesis? How does your work contribute to knowledge in your field?” In fact, as many examiners will tell you, the essence of a PhD is that it should make an original contribution. You should expect a direct question on this, such as: “What are the main novel findings or insights of your research? What have you done that merits a PhD?” Sometimes it’s phrased bluntly as “What’s new here?”

How to answer:

Be clear and explicit about your contributions. This is not the time to be modest or vague. A strong approach is to enumerate them: for example,

“My thesis makes three key original contributions: firstly, a theoretical contribution [explain how you developed or applied a theory in a new way]; secondly, a methodological contribution [explain any novel approach or data you collected that hasn’t been done before]; and thirdly, an empirical contribution [what new knowledge or evidence you provided about the phenomenon].”

Structuring it as “first, second, third” helps the examiners follow and underscores that you have multiple contributions (Scoles, 2021). For instance, you might say:

“First, my research proposes an original conceptual framework linking residents’ everyday routines to their patterns of using small urban green spaces in post-industrial cities, extending existing theories of urban public space into a more fine-grained, behaviour-focused model. Second, methodologically, I employed an innovative mixed-methods design that combines spatial data (such as mapping or GPS traces) with in-depth walking interviews, allowing richer insight into how people move through and experience these spaces than prior survey-only studies. Third, empirically, my study provides one of the first detailed datasets on the use of neighbourhood green spaces in a specific post-industrial city, revealing how factors like perceived safety, local history, and community identity shape who uses these spaces and how.”

Tailor your list to whatever genuinely was new in your project. Originality can come in various forms: maybe you studied a topic that no one else had, or you applied a known theory to a new context, or you developed a new instrument or dataset, or even if it’s a replication, perhaps you brought new insight through a more rigorous approach.

If you’re unsure what your contributions are, reflect on what you wrote in your thesis introduction or conclusion regarding originality – most theses explicitly state contributions, and examiners often pick up on those.

It is absolutely crucial that you articulate your contribution confidently. Avoid hedging like “I hope my work is original in that…” – by the viva, you should know what is original. If you don’t state it, examiners might worry you haven’t made a contribution. So even if you feel it’s obvious, spell it out clearly.

When explaining how your work differs from existing literature, it can help to reference a few key studies for contrast:

“Before my research, studies by X (2015) and Y (2017) had explored A and B, but they left issue C unexplored. My work addressed that by….”

This shows you’re aware of the scholarly context (which also implicitly answers why there was a gap needing your study). However, don’t turn this answer into a mini literature review – keep it focused on what you did that’s new.

Finally, be ready for follow-ups like “Which part of your thesis do you consider the most original?” or “What is the single most significant contribution?” Even if you have multiple contributions, the examiners might press you to identify the standout.

Think about this beforehand. It could be, for example, a particular finding that challenges existing theory. If so, be prepared to elaborate on why that finding is important and novel. Also, if your contribution is incremental (not a radical breakthrough but an important addition), that’s okay – most PhDs are evolutionary, not revolutionary. You can say something like,

“Collectively, these contributions advance our understanding of [field] by providing new evidence and refining theory. While it doesn’t overturn the field, it certainly pushes the knowledge frontier forward on X.”

Examiners appreciate a realistic assessment of contribution – neither underselling nor grandstanding, but a scholarly appraisal of how your work adds something new.

Literature review and theoretical context

Examiners will typically delve into your literature review and theory to ensure you have a solid grasp of where your work sits in the broader academic landscape. Questions in this category might include: “How did your literature review shape your research questions and design?“, “Which authors or studies were most influential on your work?” or “You mention Theory X in your thesis – can you elaborate on how you applied it, and why not Theory Y?”

They might also ask if there were alternate bodies of literature or theoretical perspectives you considered: “In retrospect, are there any other theoretical frameworks you could have used for this study?” Essentially, they want to know if you are well-grounded in the scholarly context of your research and if you can justify the conceptual choices you made.

How to answer:

Be prepared to discuss the key themes and debates in the literature that relate to your research. A strong strategy is to summarise the state of knowledge as you found it when starting your project, highlighting the gap or problem that your study aimed to address. For example:

“In my literature review, I identified substantial research on urban green spaces in major capital cities (e.g., Johnson, 2014; Patel, 2017), as well as some studies on public space use in suburban environments. However, there was relatively little work examining how residents use small neighbourhood green spaces in post-industrial towns. While existing studies such as Hassan (2013) and Clarke (2015) offered useful insights into large urban parks, they did not fully address how local history, perceived safety, and deprivation shape everyday use of smaller spaces. Recognising this gap, I focused my study on a specific post-industrial town to explore how its social and physical context influences patterns of green-space use.”

This kind of summary shows the examiners that you understood the literature landscape and that your study was needed.

When talking about which sources influenced you, mention a few of the seminal works or key theories that underpin your approach. If your theoretical framework is, say, Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory or Lefebvre’s concept of the social production of space, be ready to concisely explain that theory and why it is relevant.

“One influential theoretical framework for my research was Lefebvre’s concept of the social production of space, particularly its emphasis on how everyday practices and power relations shape the meaning of places. I applied this framework to explore how residents and local authorities jointly construct the meaning and use of small urban green spaces in a post-industrial town. This perspective allowed me to treat these spaces not just as physical locations, but as socially produced environments shaped by policy, memory, and routine behaviour. While other frameworks, such as purely ecological or behavioural models, were considered, the social production of space was better aligned with my questions because it captured the interplay between material design and lived experience.”

By explaining this, you demonstrate theoretical literacy and intentionality in your choices.

Now, regarding alternate theories or literatures: examiners love to ask this to see if you have considered other angles. Reflect on why you didn’t use certain theories. For example, if your work is rooted in social constructionism, an examiner might ask, “Why not a positivist framework?” or “Why not social constructivism instead of social constructionism?” (They sound similar but have philosophical differences – be clear on those if they apply to you.)

You can answer such questions by acknowledging the alternative and explaining your reasoning:

“I initially conceptualised community participation in fairly narrow terms, measuring it as attendance at formal meetings or events. During my data analysis, however, I realised that participants described ‘being involved’ in ways that went beyond simple attendance figures—for example, informally maintaining shared spaces, organising small neighbour-to-neighbour initiatives, or contributing local knowledge to planning discussions. This highlighted the difference between formal participation (what can be counted) and lived participation (how people actually contribute). My position evolved towards treating participation as a broader, layered construct that includes both formal and informal practices. Clarifying this shift in the discussion helped maintain theoretical consistency and made my interpretation of the data more transparent.”

This kind of answer shows you didn’t choose your theory arbitrarily – you understood the options and picked the one that best aligned with your research aims and ontology.

Examiners may also pick on specific terms or definitions from your thesis. For instance, if you initially defined “social cohesion” in a narrow way (such as levels of trust measured through a survey scale) but later wrote about it in richer, qualitative terms (including shared narratives, local identity, or informal support networks), they might ask you to clarify: “How are you conceptualising ‘social cohesion’? Are you treating it as a measurable attitude, a pattern of behaviour, or a broader relational state?”

To handle this, it’s important to show that you recognise the distinction and can explain any evolution in your thinking. You might say something like:

“At the outset, I worked with a relatively narrow survey-based definition of social cohesion, focusing on trust and perceived neighbourliness. As I analysed the qualitative data, it became clear that participants understood cohesion in a more expansive way, which included shared histories, informal mutual help, and a sense of belonging to the area. I therefore refined my working definition to incorporate both measurable attitudinal indicators and these relational, narrative dimensions. In the thesis, I tried to make this shift explicit so that my use of the term remained consistent and transparent.”

This kind of explanation directly addresses the concern, shows that you are in control of your terminology, and reassures examiners that any definitional shift was reflective and deliberate rather than accidental.

Methodology and research design

Expect a series of questions about your methodological choices. Examiners will likely ask you to explain and justify how you carried out the study. Common questions include: “What is the overall methodology underpinning your research, and why was it appropriate for your questions?“, “How did you select your participants or sample?“, “Why did you use Method A (e.g., interviews, experiments, surveys) and not Method B? Did you consider other methods?“, “What steps did you take to ensure the reliability or validity of your data?”, “What were the main challenges in collecting your data, and how did you address them?”, and “What ethical issues did you encounter and how were they handled?” Essentially, they will probe every major decision you made in designing and conducting the research to ensure it was sound and that you understand the reasoning behind it.

How to answer:

Start by clearly identifying your methodological framework. Was your research qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods? Did you take a case study approach, an ethnographic approach, an experimental design, etc.? State this upfront in your answer. For example:

“I adopted a qualitative case study methodology, focusing on four neighbourhoods as cases, because I aimed for an in-depth understanding of how residents use and experience local green spaces. A qualitative approach was appropriate given the exploratory nature of my research questions and the focus on subjective experiences.”

Or if quantitative:

“My research design was a quantitative cross-sectional survey of 200 residents, chosen to test hypotheses about the relationship between access to green spaces and self-reported wellbeing, and to achieve statistical generalisability.”

This gives the examiners a framework for your choices.

Next, justify why this approach was suitable. Tie it to your research questions:

“I was interested in how and why residents engage with small urban green spaces (which are complex, context-dependent questions), so qualitative interviews were the best fit to get rich, detailed accounts. A purely quantitative approach would not have captured the nuanced meanings people attach to these spaces, which is why I did not rely solely on a large-scale questionnaire.”

By doing this, you also pre-empt the question of “why not a different method.” Always link method to the nature of the inquiry. Examiners appreciate when you show that your methods were chosen logically, not arbitrarily or out of convenience alone.

Be ready to discuss alternative methods and why you didn’t use them. This demonstrates reflexivity. For instance:

“I considered using systematic observation in the green spaces in addition to interviews, to compare what people said they did with how spaces were actually used across the day. I ultimately decided against a full observational study mainly due to time constraints and the scope of a PhD; instead, I asked participants to describe recent visits in detail and to sketch their typical routes through the spaces. In hindsight, observations could have added another layer of data, but I did triangulate by interviewing both residents and local authority officers, which provided a form of cross-check on reported patterns of use.”

An answer like this shows you thought about it. If there were methods you wished you could have used but couldn’t (common in PhDs due to practical limits), it’s okay to say that and perhaps mention it as something to do in future research or something that could strengthen the study. Examiners know every method has limitations, so they mainly want to see that you’re aware of them and made informed choices.

Discuss your data collection process clearly: how did you recruit participants? Why that sampling strategy? For example:

“I used purposive sampling to recruit residents who had lived in the area for at least five years, to ensure they had sustained experience of the neighbourhood and its green spaces. I ended up with 20 participants across four neighbourhoods, aiming for diversity in age, gender, and housing type. This small, information-rich sample was appropriate for an in-depth qualitative study; it wasn’t meant to be statistically representative but to provide detailed insight.”

If quantitative, you might explain how you determined your sample size (e.g., power calculation or just practical constraints) and any steps to ensure it was reasonably representative.

Examiners also frequently ask about analysis (even though it’s a separate stage, it’s part of methodology). They may say: “How did you analyse your data, and why did you choose that form of analysis?” Be ready to describe, for instance, your coding process for qualitative data or the statistical tests for quantitative data.

“I transcribed all interviews and conducted a thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s approach. I chose thematic analysis because it allowed patterns to emerge inductively from participants’ accounts of their everyday use of green spaces. I systematically coded the transcripts, developed themes, and then iteratively refined these themes in relation to my theoretical framework, which ensured that the analysis was grounded in the data but also informed by existing theory.”

If you used software (like NVivo or SPSS), you can mention that as a tool, but emphasise the analytical logic (the software is just a tool).

For quantitative work:

“I first tested the reliability of my survey scales (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 indicated good internal consistency). Then I performed descriptive statistics to summarise the data and used regression analysis to test hypotheses about predictors of self-reported wellbeing and frequency of green-space use. Regression was suitable to isolate the effect of each factor (such as distance to the nearest park, perceived safety, or income) while controlling for others.”

Be prepared to justify any statistical choices (why that test, was your sample size sufficient, etc.) or any qualitative trustworthiness measures (did you use triangulation, member checking, inter-coder agreement?). If you haven’t explicitly done some, you can still comment:

“While I was the sole coder, I discussed a sample of transcripts with a fellow PhD student to get an external perspective and ensure my interpretations were not too biased. This informal peer review helped improve the reliability of my thematic coding.”

Ethics is another area likely to be queried: “What ethical considerations arose, and how did you address them?” Make sure to mention how you obtained informed consent, assured confidentiality (e.g., pseudonyms for participants and neighbourhoods), and any approval by an ethics committee.

If there were sensitive issues (e.g., residents criticising local authorities or raising concerns about safety in specific locations), mention how you protected participants’ identities. A good answer might be:

“All participants signed informed consent forms after I explained the study aims and their rights to withdraw at any time. I ensured anonymity by assigning codes to each participant and referring to neighbourhoods with pseudonyms – only I know the real identities. Because this is a relatively small town, I was careful in the write-up to avoid including detailed descriptions that could make individuals identifiable. I also faced an ethical consideration when one participant became visibly upset while describing a violent incident in a nearby park; I paused the interview, checked on her wellbeing, reminded her she did not have to continue, and offered information about local support services. I debriefed participants after the interviews as well. The study had full ethics approval from my university’s review board.”

This level of detail shows you took ethics seriously.

Be honest about challenges and limitations in your methods, because examiners will likely ask something like: “What were the main limitations of your methodology, and how did you mitigate them?” Identify a couple of limitations yourself (this shows critical self-awareness). For example:

“One limitation was the relatively small number of neighbourhoods – since I focused on four case study areas within a single town, the findings are not broadly generalisable to all post-industrial towns. I mitigated this by choosing neighbourhoods that varied in terms of deprivation levels and proximity to green spaces, to capture some diversity. Still, the work is exploratory. Another limitation was potential researcher bias in interpreting qualitative data, since I also live in the town and use some of these spaces myself. I kept a reflexive journal throughout the project and used extended verbatim quotations in the thesis to let participants’ voices be heard directly, which helped to counteract this bias.”

Pre-emptively discussing limitations demonstrates maturity as a researcher. It’s much better that you point them out rather than an examiner cornering you with a flaw and you being defensive. Most examiners actually appreciate when a candidate shows they know their study isn’t perfect but can explain why decisions were made and how issues were handled.

Analysis and findings

Examiners will certainly ask about your findings – after all, these are the heart of your thesis. Typical questions might be: “What are the most important findings to emerge from your study?”, “Did any findings surprise you?”, “How do your findings relate to or confirm/challenge existing theories or literature?” They might take you through each results chapter and ask specific questions about what you found. If your thesis has multiple studies or parts, they may ask, “Briefly summarise the main findings of each part and how they link together.” Another angle: “Were there any results that you didn’t expect, and how did you explain them?” or “If any data didn’t fit your initial expectations or conceptual framework, what do you make of that?”

How to answer:

Have a clear narrative of your key findings ready. This is like the “findings story” of your thesis. A good strategy is to highlight about two to four main findings (depending on the complexity of your work) that answer your research questions. For example:

“The first major finding was that usage of small neighbourhood green spaces was highly unequal: residents in more affluent streets visited them regularly, while people in the most deprived streets often avoided them altogether because of safety concerns or poor maintenance. Secondly, I found a clear mismatch between how planners imagined these spaces would be used (as sites for leisure and social interaction) and how residents actually used them – many treated them primarily as transit routes rather than destinations. A third significant finding was the role of local history and identity: some spaces were strongly associated with past industrial uses or earlier community conflicts, which still shaped how people felt about spending time there. Finally, an unexpected finding was that even very small design interventions, such as adding benches or improving lighting in one site, led to noticeable changes in who used the space and when, suggesting that relatively modest changes can have disproportionate effects on perceived accessibility.”

That’s just an example, but you see the pattern: state each finding succinctly and, where possible, mention why it matters. essentially, you are telling the examiners, “here is what we didn’t fully know before, and here is what my research adds.”

It is also important to link your findings back to your research questions or hypotheses. ideally, structure your summary around answering each research question. If the examiners ask “what are your main findings?”, you could respond along the lines of:

“In answer to my first research question, I found that… [finding]. for the second question, the evidence showed… [finding].”

This ensures you directly demonstrate that you addressed what you set out to investigate.

Be prepared to discuss how your findings align with or challenge existing literature. If your results confirm previous studies, say so: for example,

“This pattern broadly supports what Smith (2015) found in larger city parks, reinforcing the idea that perceived safety is a key predictor of use.”

If your results differ, the examiners will be interested in why:

“Unlike Jones (2018), who reported little difference in use between more and less deprived neighbourhoods, I found substantial variation. One reason may be that Jones focused on flagship parks in a capital city, whereas my study examined small local spaces in a post-industrial town where the legacy of deindustrialisation is more visible. This suggests that context can strongly mediate how green-space provision translates into actual use.” showing that you have thought about why your findings look the way they do, in light of the literature, is crucial.”

When asked about surprises or unexpected results, don’t be afraid to acknowledge them – examiners often enjoy discussing these because they can open interesting theoretical or practical questions. you might say something like:

“I was surprised to find that one of the most heavily used green spaces in my study was also the one with the least formal facilities – no play equipment, no formal paths – just an open, slightly scruffy field. based on the literature, I had expected better-equipped spaces to be more popular. on reflection, I think this field’s central location, its lack of clear rules, and its flexibility for different activities made it attractive for a wide range of users. this suggests that informality and openness may matter as much as formal provision, which could be explored further in future work.”

This kind of reflection shows that you can think critically about your data and use it to refine or question existing assumptions.

Examiners may also drill down into specific data points: for example, “on page 85, you report that 60% of respondents said they never visit their nearest green space. were you surprised it was so high, and how do you interpret that?” Make sure you revisit any important figures or tables in your thesis beforehand and remind yourself what they show. If you made an interpretation in the thesis, be ready to stand by it or develop it further. It’s fine if, with hindsight, you can now see additional nuances that were not fully drawn out in the written text – the viva is a chance to expand the discussion.

Another common line of questioning concerns anomalies or outliers. If there were participants or sites that did not follow the general pattern, examiners may ask, “why do you think this case was different?” try to offer a reasoned view, even if you cannot be certain. for instance:

“Yes, one neighbourhood park did not fit the overall trend – it was well maintained and centrally located, yet it was rarely used. interviews suggested that a serious incident there a few years ago had given it a lasting stigma. although this is only one case, it indicates that past events and local narratives can override physical quality, which is something future research could explore more systematically.”

Lastly, examiners might ask how confident you are in your findings or whether you considered alternative explanations. be honest but positive. you might say:

“Given the consistency of the patterns across different data sources – survey responses, interviews, and my field notes – I am reasonably confident in the main conclusions, though I would be cautious about generalising beyond similar towns. There are alternative explanations for some patterns, such as seasonal effects or changes in local policy, and I tried to address these by [for example, collecting data across several months, checking local council records, or comparing neighbourhoods with different policy histories].”

This shows you have a critical mindset rather than treating your findings as unquestionable.

Discussion, implications and contributions to practice or policy

Beyond the immediate findings, examiners often move to ask about the implications of your research. This can overlap with the earlier “significance” questions, but here it’s usually more focused on what your findings mean for the field or for real-world applications. You might be asked: “What are the implications of your findings for practice or policy?”, “How do your conclusions impact the wider discipline or industry?”, “Who are the beneficiaries of this research and how might they benefit?”, or “If you were to communicate your findings to, say, policymakers or practitioners, what would you say?” Examiners want to see that you have thought about how your research can be used.

How to answer:

First, distinguish between academic implications and practical ones. Academic implications relate to how your work advances knowledge, which you will have already discussed under originality, but you can reiterate or extend them. For example:

“Theoretically, my work suggests we need to refine how we think about neighbourhood green spaces in post-industrial towns. Existing models tend to treat them as neutral amenities, but my findings show they are deeply shaped by local history, perceived safety, and patterns of everyday movement. Future studies may need to incorporate these social and historical dimensions more explicitly when conceptualising urban public space.”

Practical implications concern policy, professional practice, or other real-world arenas. For instance:

“For local authorities and urban planners, one implication is that simply providing a certain number of green spaces is not enough. My findings highlight that design quality, lighting, and how safe spaces feel after dark strongly influence who uses them and who stays away. Planning guidance could therefore place greater emphasis on improving perceived safety and inclusive design in existing small spaces, not just creating new ones on a map.”

Try to give concrete examples. If your research has implications for policymaking, articulate what policy or guidelines could be influenced:

“In the town I studied, the current regeneration strategy focuses heavily on a single flagship park. My results suggest that modest, targeted improvements to smaller neighbourhood spaces – such as better lighting, seating, and paths – may deliver greater everyday benefit for residents who cannot easily travel to the main park. If I were advising the council, I would recommend rebalancing investment so that local spaces in deprived areas receive more attention, rather than concentrating resources in one high-profile site.”

If your work is more theoretical, the main implications may be for future research directions. For example:

“This study opens up several avenues. One is the need for longitudinal research on how changes to local green spaces affect use over time, rather than relying on a single snapshot. Another is comparative work between different post-industrial towns, to see whether the patterns I found – especially the role of stigma and local history – also appear elsewhere. These studies would help to test and extend the framework I developed.”

Another typical question is: “Who will benefit from your research?” This is essentially about impact. You might say something along the lines of:

“Residents are key beneficiaries, especially those in areas currently underserved by good-quality green spaces. If local policy takes up these findings, they may see more accessible, safer, and better-maintained spaces in their neighbourhoods. Urban planners and regeneration teams can benefit by having evidence about how people actually use small spaces, rather than relying on assumptions based on larger city parks. Public health practitioners and community organisations may also find the results useful when designing interventions that encourage physical activity and social connection in local environments.”

You should tailor this to your own project, but the key is to show you have thought about the value or use of your work beyond simply obtaining the degree.

One caution: keep your implications realistic and within the scope of your findings. Don’t over-claim. For example, if you carried out a small qualitative case study, you would not say, “This definitively proves national planning policy must change,” because single-case studies rarely justify sweeping reforms on their own. Instead, you might say something like:

“The research suggests that any future regeneration policy in towns like this should involve meaningful consultation with residents about how they actually use and experience existing green spaces. My findings indicate possible resistance or under-use if these lived experiences are ignored, so involving communities early on could make policy more effective.”

This shows prudence. Examiners often check that you are not drawing conclusions beyond what your data can reasonably support, so always align your claimed implications with the strength and scope of your evidence.

Finally, examiners might ask how you plan to communicate your results or whether you intend to publish them. They sometimes end with a forward-looking question such as: “If you were to present your findings to local decision-makers, what would you emphasise?” or “Have you considered publishing this work or sharing it with the council or community groups?” You can mention any publications in progress or your dissemination plans. For example:

“Yes, I plan to submit at least one journal article focusing on the conceptual framework for understanding small urban green spaces, and another that presents the empirical findings for an urban planning or urban studies audience. I have also prepared a short, accessible summary of the results for the local authority and community organisations involved in the study. I think it is important to feed the findings back to those stakeholders, and I hope it will inform their ongoing discussions about neighbourhood regeneration.”

Limitations and areas for further research

Virtually every viva will include a question about limitations or what you would do differently. Examples: “What are the limitations of your study and how have these influenced your results?”, “If you were to do this research again, what would you change or improve?”, or “What further research does your work suggest is needed?” Sometimes it’s phrased as “Knowing what you know now, how would you design a follow-up study?” These questions test your ability to critique your own work and to see beyond it.

How to answer:

First, acknowledge the limitations of your work candidly – every study has them, and examiners want to see that you are not blind to them. We touched on methodological limitations earlier; here you can broaden out to any aspect. Common limitations include: sample size or composition, generalisability, potential biases, and constraints of time or resources. You should already have identified many in your thesis (usually in a “limitations” subsection). Reiterate the key ones, for example:

“One clear limitation is that my study focused on four neighbourhoods in a single post-industrial town, so other towns or cities might show different patterns of green-space use. The data was also collected at one point in time, so I could not capture seasonal variation or the impact of future regeneration projects. Additionally, my qualitative data relies on self-report in interviews, which means residents may have under- or over-reported their use of green spaces, or presented themselves in a slightly more positive light. I tried to mitigate this by triangulating with field observations and being explicit about anonymity, but it remains a consideration.”

By stating these yourself, you demonstrate critical thinking and self-awareness.

When discussing how limitations influenced results, you can make the connection explicit:

“Given the small and context-specific sample, I treat the findings as exploratory: they highlight important patterns, but I would not generalise them uncritically to all post-industrial towns. The reliance on self-report means that some apparent discrepancies between people’s stated appreciation of green spaces and their actual frequency of use should be interpreted with caution. Ideally, future work would combine self-report with systematic observation or usage data to confirm these patterns.”

Now, for the “what would you do differently” part: examiners don’t expect you to redo your PhD, but they do want to see that you’ve learned from the process. Pick one or two things you would adjust and explain why, without undermining your own study:

“If I were starting again, I would build in a modest observational component across the four neighbourhoods, for example short structured observation sessions at different times of day and week. That would allow me to compare residents’ accounts with observed patterns of use more directly. I would also consider extending the design to include a second town with a different regeneration trajectory, to see whether the relationships I found between history, perceived safety, and use are specific to this place or appear in other settings too. Those changes weren’t feasible within the time and resource constraints of this PhD, but they would strengthen a follow-up study.”

Sometimes the question is phrased as “What have you learned from doing this research project?” In that case, you might combine methodological lessons and substantive insights:

“Methodologically, I learned how important it is to pilot interview guides and mapping tasks; my first version was too abstract, and early participants struggled, so I revised it to include more concrete prompts and examples. Substantively, I learned that residents’ relationships with green spaces are much more layered than I initially assumed – they are tied not only to convenience and facilities, but also to memories, informal rules, and local reputations. If I were starting again, I would build this complexity into my design from the outset, rather than treating it as an afterthought.”

For further research, be ready with a few ideas that logically flow from your findings and limitations. For example:

“Further research could involve a larger-scale survey across several post-industrial towns, to test whether the patterns I identified – especially the uneven use of small neighbourhood green spaces – hold more broadly. A longitudinal study following residents over time, particularly during and after regeneration projects, would help show how changes to local spaces affect everyday use and perceptions. Another follow-up could be an intervention study: co-designing small improvements with residents in one or two parks and then evaluating whether those changes alter who uses the spaces and how. That would directly test the practical value of the suggestions I develop in the thesis.”

Examiners appreciate hearing specific, realistic future directions; it shows that you are thinking like a researcher beyond the current project.

Be careful, however, not to imply that your own study was pointless. It’s easy, when criticising yourself, to sound overly negative. Balance any discussion of limitations by reaffirming what was strong:

“Despite these limitations, I believe the study offers valuable insights as an in-depth qualitative exploration of how residents in one town use and perceive local green spaces. It provides a foundation on which larger or more comparative studies can build. The aim was never to say everything about urban green spaces, but to uncover X, Y, and Z, which stand as meaningful contributions in their own right.”

In short, demonstrate self-awareness and growth. Show that you can step back and view your work with a critical eye, identifying both weaknesses and ways to address them in future research. This reassures examiners that you have the maturity of a scholar – someone who can evaluate research (including their own) and continually refine it. Many examiners comment that strong candidates mention most of their study’s main limitations before the examiners have to; if you can do that, you often leave them with little to criticise, because you’ve shown that you already understand the issues and have thought them through.

Personal reflection and closing questions

Towards the end of the viva, examiners often switch to more reflective or even semi-personal questions. These serve to end the discussion on a lighter note and also to gauge your self-reflection as a researcher. Common ones include: “What was the most interesting or exciting part of your research journey?”, “Which part of the research did you enjoy the most, and which part was the most challenging?”, “How have you developed as a researcher during your PhD?”, or “If you were to give advice to a new PhD student based on your experience, what would it be?” Sometimes an examiner might ask, “What have you learned about yourself in doing this project?” or even the slightly playful, “Would you do it again?”.

While these questions are not about testing knowledge, they are still important. They humanise the viva and allow you to show some personality and insight. It’s good to have thought about these so you’re not caught off guard (after a long technical grilling, suddenly talking about feelings can be surprising!).

How to answer:

Be honest and positive. Identify something that genuinely fascinated you. For example:

“The most interesting part for me was walking through the neighbourhoods with participants and hearing how they described familiar streets and green spaces in their own words. There was a real moment of discovery when I started hearing similar stories and concerns repeated in different areas – it felt like I was uncovering a pattern that hadn’t been documented before.”

This shows your engagement. For the most challenging part, you might say something like:

“Analysing the qualitative data was probably the toughest phase – I had hours of interviews and field notes, and at first it felt overwhelming. Learning how to code and theme systematically was a challenge, but once I developed a clear coding framework, it became much more manageable. It taught me a lot about handling complex datasets and making careful, defensible interpretations.”

This doubles as a reflection on skill development.

When asked how you’ve developed as a researcher, consider mentioning skills or mindset changes:

“I’ve definitely become much more confident in my critical thinking. At the start, I tended to accept what the literature said at face value; now I find myself questioning, comparing, and synthesising ideas more actively. I’ve also learned to manage a long-term project from start to finish, which included time management and dealing with setbacks – for example, when my initial access to one neighbourhood fell through, I had to renegotiate with gatekeepers and adjust my sampling strategy. Overall, I feel I’ve grown from being a student to being an independent researcher who can identify a problem, investigate it rigorously, and communicate the findings. I’ve also learned to tolerate uncertainty better – research can be unpredictable, and I’m much more comfortable with that now.”

Examiners love to see that you’re self-aware and have indeed undergone the “PhD journey” of growth.

If they ask what you would advise others or whether you would do it again, feel free to be a bit light-hearted but still diplomatic:

“I would do it again – though perhaps not immediately and with a few refinements – but overall it has been a rewarding journey. My advice to a new PhD student would be: stay organised, stay curious, and don’t be afraid to ask for help when you need it. Also, keep reminding yourself why you started; that underlying motivation really helps when the project feels heavy.”

Such answers show you have perspective beyond just your own project.

Sometimes the very last question is deliberately easy, like: “Is there anything we haven’t asked that you wish we had, or anything you’d like to add?” This is basically an invitation for you to finish on any note you choose. It’s perfectly fine to say:

“I think we’ve covered everything important, thank you – I’ve appreciated the chance to discuss the work in depth.”

Or, if there is a point you really wanted to mention but didn’t get to, you could briefly include it here:

“We didn’t talk much about the small pilot study I did at the beginning, which also gave me some useful insights into how people navigate these spaces, but that’s covered in the appendix. Overall, I’m happy with what we’ve discussed.”

This ensures you don’t leave with regrets about something unsaid.

Another question that occasionally comes up is: “What are your plans after the PhD?” Not every examiner asks this, but if they do, it’s usually conversational. You can mention if you plan to publish papers, pursue an academic career, move into industry, work in the public sector, or return to a professional role – whatever is accurate for you. There is no single “right” answer; they just want to see you looking ahead. If relevant, you can connect it to your research:

“I’d like to continue working in urban planning and policy, ideally in a role where I can use this research to inform decisions about neighbourhood regeneration and public space. I also plan to publish at least one article from the thesis so that the findings can reach a wider academic and professional audience.”

Answering these personal and reflective questions with clarity and sincerity is a good way to close the viva. It shows that beyond the academic work, you have also developed as a person and as a professional. Examiners often enjoy ending on this note because it emphasises that a PhD is not only about data and analysis, but also about forming a thoughtful, reflective scholar. It can leave a positive final impression of you as a balanced person who is ready to take the next step as a doctor in your field.

If you’re looking for reliable PhD help from PhD-qualified experts – from proposal writing and dissertation planning to full PhD thesis writing, editing, and viva preparation – our PhD writing service can support you throughout the process. Explore our PhD dissertation help services or get in touch with our friendly team to discuss what you need.

References and further reading:

- Bhatt, I. (2014). Key questions for the viva voce. Ibrar’s Space [Blog], 26 November. Available at: https://ibrarspace.net/2014/11/26/key-questions-for-the-viva-voce/ (Accessed 10 December 2025).

- Chow, E. (2016). The Viva: Preparing for the PhD exam. [Blog] 11 February. Available at: https://edchow.wordpress.com/2016/02/11/the-viva-preparing-for-the-phd-exam/ (Accessed 10 December 2025).

- Delamont, S., Atkinson, P. and Parry, O. (2004). Supervising the Doctorate: A Guide to Success. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- DiscoverPhDs (n.d.). PhD Failure Rate – A Study of 26,076 PhD Candidates. Available at: https://www.discoverphds.com/advice/doing/phd-failure-rate (Accessed 10 December 2025).

- Roberts, C.M. (2004). The Dissertation Journey: A Practical and Comprehensive Guide to Planning, Writing, and Defending Your Dissertation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Scoles, J. (2021). “Vive-ing La Viva: How to answer viva questions.” Teaching Matters [Blog], University of Edinburgh, 17 August. Available at: https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/teaching-matters/vive-ing-la-viva-how-to-answer-viva-questions/ (Accessed 9 December 2025).

- Thomas, R.M. and Brubaker, D.L. (2000). Theses and Dissertations: A Guide to Planning, Research, and Writing. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

- Tinkler, P. and Jackson, C. (2004). The Doctoral Examination Process: A Handbook for Students, Examiners and Supervisors. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- UWS London (2023). What is a PhD viva? [Blog] University of the West of Scotland – London. Available at: https://www.uwslondon.ac.uk/blog/phd-viva/ (Accessed 9 December 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: