Lewin’s change management model: a guide

Info: 2126 words (9 pages) Study Guides

Published: 10 Dec 2025

Working on a leadership or organisational change assignment with Lewin’s change model? Our UK-qualified writers can help you deliver high-quality work that stands out. Visit our management assignment help page for more info.

Lewin’s change model is a foundational framework for understanding and managing organisational change. Developed by social psychologist Kurt Lewin in the mid-20th century, the model presents change as a structured process with clear stages.

It remains widely taught and applied in academic and professional settings, reflecting its lasting relevance to contemporary organisational change practice.

This guide explains Lewin’s three-step model – unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. It also explores the theory, practical applications, and ongoing importance of the model today.

Origin and background of Lewin’s change model

Kurt Lewin introduced his model of planned change in 1947, an era when organisations were often seen as relatively stable systems facing periodic disruptions (Lewin, 1947).

As a pioneer in social psychology and organisational behaviour, Lewin sought to understand how to effectively shift group behaviours and norms. He proposed that successful change requires a deliberate break from the status quo, a carefully managed transition, and a consolidation of new practices. This perspective was rooted in Lewin’s broader “field theory,” which viewed the current state as a dynamic equilibrium of forces that can be shifted by altering driving and restraining pressures.

In practical terms, Lewin’s work gave rise to the notion of force field analysis – a technique for analysing the factors supporting or resisting change (Lewin, 1951).

By conceptualising change as a move from one equilibrium to another, Lewin provided a simple yet powerful blueprint for managers and scholars.

However, it is important to note that the famous three-step phrasing “unfreeze–change–refreeze” was distilled from Lewin’s ideas and popularised after his death (Cummings et al., 2016). Regardless of its exact origin, the three-step model became a foundation for planned change methodology in subsequent decades.

Stages of Lewin’s change model in organisational change

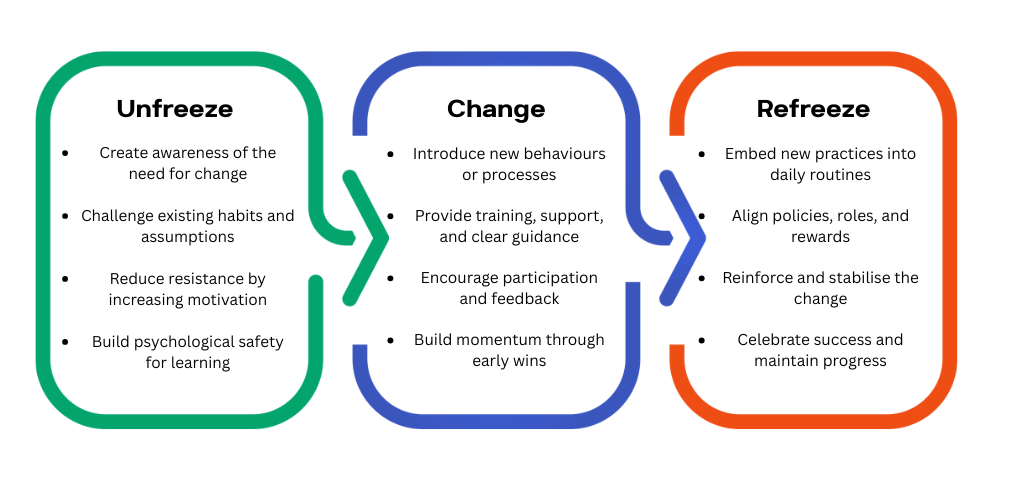

Lewin’s model divides the change process into three core stages: unfreezing, changing (or moving), and refreezing (Lewin, 1947).

Each stage addresses a critical aspect of achieving lasting change. The model is often explained with an ice analogy. Imagine you have a cube of ice but want to reshape it into a cone. First, you must melt the ice. Then you pour it into a mould for the new shape. Finally, you allow it to solidify again. This shows how Lewin’s stages involve loosening the current state, shifting to a new one, and then making it stable.

Unfreezing in organisational change

Unfreezing is about preparing an organisation to accept that change is necessary.

In this initial stage, the focus is on dismantling existing mindsets and overcoming inertia. Leaders actively create awareness of problems or opportunities and so highlight why current practices can no longer continue. This often involves presenting clear evidence and data that challenge complacency. Because people resist losing what feels familiar, leaders must deliberately ‘shake up’ the status quo.

Lewin argued that behaviour in organisations tends to reside in a quasi-stationary equilibrium sustained by a balance of driving forces (push for change) and restraining forces (push against change). To initiate change, managers must increase the drivers or reduce the resistors, thereby “unfreezing” the equilibrium. For example, a company facing declining customer satisfaction might unfreeze by sharing survey data that underscores the need for a new customer service approach.

According to Schein (1996), successful unfreezing also entails creating psychological safety: individuals need to feel safe letting go of old habits and learning new ones. By reducing “learning anxiety” (the fear of the unknown or of incompetence in a new system), leaders can therefore overcome defensive resistance and open employees to new ideas (Schein, 1996).

Changing

Once the organisation is unfrozen and ready to move, the change phase is when new approaches are introduced.

At this stage, people begin to learn and adopt new behaviours, processes, or ways of thinking. It is inherently a period of uncertainty and experimentation, yet it is also when the planned changes become real.

Effective change implementation involves clear communication of the vision, ongoing support, and engagement of those affected. Leaders should provide training, resources, and encouragement to help individuals navigate the new ways of working. It is important to recognise that change is not instantaneous; there may be a gradual shift as employees explore and gradually accept the new practices. During this phase, visible short-term wins and role models can bolster confidence.

For instance, if a hospital is implementing a new digital records system, the change stage would include:

1. the rollout of the software

2. staff training sessions

3. troubleshooting issues as they arise.

Furthermore, managers should continuously communicate the benefits of the change. They should also adjust their strategies in response to feedback to ensure momentum is maintained throughout the transition.

Refreezing

Refreezing is the process of solidifying and stabilising the new state after the change.

In this final stage, the goal is to embed the new behaviours or processes into the organisational culture so that they endure. Without refreezing, changes can be temporary, with people reverting to old habits once initial pressures subside. Therefore, leaders must reinforce the changes through mechanisms such as:

- updated policies

- reward systems aligned with the new behaviours

- ongoing training or support

It can involve documenting new procedures, establishing new norms, and even restructuring organisational roles to fit the change. The idea is to make the new way “the new normal.”

As an example, after successfully overhauling its customer service process, a business would refreeze by:

- updating job descriptions

- integrating the new service standards into performance evaluations

- celebrating the successes achieved through the new approach

Refreezing does not imply that future change will never occur; rather, it ensures that the current change sets firmly enough to withstand pressures and thus prevents backsliding

In modern fast-changing environments, some theorists suggest that refreezing may be more about achieving a reasonable stabilisation rather than a permanent freeze, acknowledging that continuous improvement will eventually trigger another cycle of unfreezing (Burnes, 2004).

Applications in modern organisations

Lewin’s change model has proven adaptable and remains in use for a variety of change initiatives today. Its simplicity makes it a practical planning tool across industries and sectors.

Using Lewin’s model for planned, incremental change

Managers frequently turn to the unfreeze-change-refreeze framework when orchestrating planned, incremental changes such as implementing a new technology system or reorganising a department. In such cases the model serves as a checklist to ensure the human side of change is addressed:

- Leaders communicate the need for change early (unfreezing).

- The change is implemented with appropriate support and participation (changing).

- New practices are embedded and reinforced to ensure they are sustained (refreezing).

The model’s enduring influence is evident in many modern change methodologies that echo its stages. For example, popular guides to change often start with building urgency or awareness (paralleling unfreezing) and end with sustaining the change (paralleling refreezing), even if they use different terminologies.

Applying Lewin’s model in large-scale or rapid change

Importantly, Lewin’s framework is not limited to minor changes. Change agents have also applied Lewin’s framework – sometimes with modifications – to large-scale transformations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, organisations had to rapidly shift their operations (from on-site to remote work, or retooling production lines for new products) almost overnight.

In such scenarios, change leaders still invoked Lewin’s principles:

- They first “unfroze” by convincing employees that the usual ways of working had to be abandoned immediately due to the crisis.

- They pivoted to new practices (mass adoption of remote collaboration tools or emergency protocols)

- Later they “refroze” by standardising these practices for the new normal.

The speed of change was unprecedented, yet Lewin’s stages provided a mental model to ensure nothing was overlooked – even if this final stage had to remain flexible, serving as a provisional stabilisation until the next adaptation.

Lewin’s model in contemporary practice

The continued use of Lewin’s model in contemporary change efforts – from digital transformation projects to culture change programmes – demonstrates its versatility and fundamental logic.

Practitioners often combine Lewin’s approach with other tools (such as stakeholder analysis or agile project methods), illustrating that the three-step model serves as a foundational scaffold that can integrate with newer techniques rather than compete with them.

Benefits and limitations

Strengths of Lewin’s change model

Lewin’s change management model offers several enduring strengths.

Firstly, its simplicity and clarity make it accessible – managers and employees can easily grasp the concept of three clear phases, which provides a straightforward roadmap for change. This clarity helps ensure that critical steps (like preparing people and consolidating change) are not overlooked.

The model also emphasises the human element of change: it recognises that inertia and resistance are natural, so proactive efforts are needed to overcome them. By explicitly including an “unfreezing” stage, Lewin’s framework encourages leaders to invest time in creating readiness, which is arguably a prerequisite for any successful change. Likewise, the refreezing stage highlights the often-neglected need to follow through and embed changes, thereby reducing the risk of backsliding.

Another strength is that the three-step model is broadly applicable and flexible – it does not prescribe specific actions but rather a general approach, allowing it to be adapted to different contexts. Indeed, many practitioners value it as a foundational mental model that can integrate with more detailed change tools or newer methodologies, ensuring basic principles of change management are kept in focus.

Criticisms and limitations

Despite its influence, Lewin’s model has faced criticism over the years. One common critique is that the model is too simplistic and linear to capture the complexities of organisational change in modern, dynamic environments. Change in real organisations is often continuous and iterative rather than a neat three-step sequence. Critics argue that the notion of “refreezing” an organisation is less applicable when firms must adapt constantly to technological advances and global competition.

However, defenders of Lewin note that critics often misinterpret his ideas – Lewin never meant refreezing to imply a permanent static state, but rather the need to stabilise changes at least for a time (Burnes, 2004).

Another criticism is that the three-step model seemingly ignores power and politics within organisations, and that it assumes change is a top-down, management-driven process (Burnes, 2004). Later scholars observed that real change often involves bargaining, conflict, and bottom-up influences. These emergent elements are not fully captured by a simple stage model. Lewin initially developed his model with small-scale changes and group dynamics in mind. As a result, some question its suitability for complex transformational change.

In response, it can be said that Lewin’s framework is a starting point – it provides an overarching structure, but change leaders may need to incorporate analysis of power relations, stakeholder interests, and iterative feedback loops to manage large transformations effectively.

Indeed, Lewin’s legacy lies in establishing that successful change is a process, not an event, even if the process may need to be elaborated beyond three steps in contemporary practice.

Conclusion

Kurt Lewin’s change management model continues to be a cornerstone in the study and practice of organisational change. Indeed, its enduring popularity stems from the elegant simplicity with which it captures a universal truth: meaningful change requires careful preparation, thoughtful execution, and sustained reinforcement.

Even though later theories have expanded and refined approaches to change, Lewin’s three-step model remains deeply relevant. It underlines that behind every successful change initiative – whether a minor process update or a major strategic transformation – there is a process that helps people let go of the old, navigate the transition, and settle into the new.

Ultimately, in a world of constant change, Lewin’s framework reminds us that change is not just a technical adjustment but a human journey. By appreciating the need to unfreeze minds, manage the moving phase, and refreeze new behaviours, today’s leaders and change practitioners can thus draw upon Lewin’s timeless insights to increase the likelihood that changes take root and deliver lasting results.

If you need support with leadership or organisational change coursework, our UK-trained academic writers can help you craft strong, well-structured assignments. See our management assignment help page for more details.

References

- Lewin, K. (1947) Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept, Method and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change. Human Relations, 1(1), pp. 5–41.

- Lewin, K. (1951) Field Theory in Social Science. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Burnes, B. (2004) ‘Kurt Lewin and the Planned Approach to Change: A Re-appraisal’, Journal of Management Studies, 41(6), pp. 977–1002

- Cummings, S., Bridgman, T. and Brown, K.G. (2016) ‘Unfreezing change as three steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s legacy for change management’, Human Relations, 69(1), pp. 33–60

- Schein, E.H. (1996) ‘Kurt Lewin’s change theory in the field and in the classroom: Notes toward a model of managed learning’, Systems Practice, 9(1), pp. 27–47

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: