Lean Six Sigma guide

Info: 4366 words (17 pages) Study Guides

Published: 29 Dec 2025

Struggling with a lean six sigma assignment? Get expert support with process mapping, DMAIC, data analysis, and improvement reports through our trusted business assignment help service.

Lean Six Sigma is a comprehensive process improvement methodology. It combines two complementary strategies – lean and Six Sigma – to drive operational excellence. It merges lean’s focus on eliminating waste with Six Sigma’s focus on reducing variability and defects. This combined approach improves efficiency and quality simultaneously (Pepper and Spedding 2010; Snee 2010). In practice, Lean Six Sigma provides organisations with a structured framework to streamline processes, enhance customer satisfaction, and boost bottom-line results (Snee 2010).

Bill Smith originally developed Six Sigma at Motorola in the 1980s, and manufacturers in Japan and the U.S. had already been using “lean” techniques for waste reduction – Lean Six Sigma represents the convergence of these approaches. Lean Six Sigma was initially proven in manufacturing environments. It has since been adopted across healthcare, finance, government and other sectors. This widespread use is due to its robust and adaptable approach to achieving continuous improvement (George 2002; Laureani and Antony 2012).

This guide presents a detailed overview of Lean Six Sigma – covering its origins, principles, methodology, tools, roles, benefits, and implementation considerations. The aim is to illustrate how Lean Six Sigma can deliver lasting improvements in diverse business environments.

Origins and evolution

Lean Six Sigma emerged from the convergence of two proven improvement paradigms that rose to prominence in the late 20th century. Lean principles originated with the Toyota Production System in post-war Japan. This approach emphasised the relentless elimination of waste (muda) and the creation of value through efficient workflows.

Authors like Womack and Jones (1996) popularised these ideas in the West. They identified five core lean principles (Womack and Jones 1996). These principles are:

- specify value from the customer’s perspective;

- map the value stream for each product or service;

- establish smooth flow in processes;

- let customer demand pull work through the system; and

- pursue perfection through continuous improvement.

By the 1980s, lean methods (often simply called “lean manufacturing”) had delivered dramatic improvements in industries like automotive. This success demonstrated the importance of cultivating a culture of continuous improvement and respecting frontline workers’ input (Womack and Jones 1996).

Engineer Bill Smith and his colleagues developed Six Sigma at Motorola in 1986. Their aim was to drastically reduce defect rates using statistical tools and a rigorous project methodology (Hayes 2025). The term “Six Sigma” denotes a level of process performance equivalent to at most 3.4 defects per million opportunities. In other words, six standard deviations fit between the process mean and the nearest specification limit. This level of process capability means that practically all output meets the desired specifications.

Six Sigma seeks to reduce variability in processes to ensure results are consistently within those specifications. It relies on systematic data collection and analysis to identify root causes of defects and variation. Solutions are then implemented along with strict process controls to prevent any regression of performance.

General Electric’s high-profile success with Six Sigma in the 1990s (under CEO Jack Welch) further boosted the methodology’s popularity. GE reported hundreds of millions of dollars in savings from Six Sigma projects. This success prompted many other organisations to take notice and launch their own quality initiatives (George 2002).

By the late 1990s (and into the early 2000s), countless companies had dedicated Six Sigma programmes. These programmes employed trained specialists (Green Belts, Black Belts, etc.) who executed projects to tackle quality problems.

Practitioners soon recognised that lean and Six Sigma address complementary aspects of process improvement. Lean’s strength was speed and waste elimination, while Six Sigma’s strength was problem-solving depth and variability reduction.

Michael George (2002) and others helped popularise the unified concept of Lean Six Sigma around 2001–2002. The idea was to harness the best of both worlds. Lean tools free up capacity and eliminate waste, while Six Sigma’s statistical methods bring processes under tight control with minimal defects (Pepper and Spedding 2010; George 2002). Rather than viewing lean and Six Sigma as competing initiatives, Lean Six Sigma frames them as a single continuous improvement system. It is aimed at “business and operational excellence” (Snee 2010).

Since the 2000s, Lean Six Sigma has evolved into a standard approach for organisations worldwide. It now extends beyond manufacturing into services, healthcare, software development, supply chains and more. It continues to adapt. For example, modern Lean Six Sigma applications integrate automation and advanced analytics. However, the core principle remains the same: systematically remove waste and defects to improve performance, regardless of the industry or process.

Lean principles

To understand Lean Six Sigma, it is crucial to grasp the fundamentals of its two component methodologies. The lean philosophy centres on maximising value and eliminating waste in processes. Lean thinking encourages organisations to define value through the eyes of the customer. It then calls for optimising the value stream (the sequence of activities required to deliver a product or service). This is done by removing any steps that do not add value (Womack and Jones 1996).

Commonly cited categories of waste include defects, overproduction, waiting (idle time), unnecessary transportation, excess inventory, unnecessary motion, over-processing, and unused talent. These eight wastes are commonly remembered using the mnemonic DOWNTIME (or TIMWOOD), which is widely used in lean training to help practitioners identify non–value-added activities quickly. By systematically attacking these wastes, lean improves process speed, cost efficiency and quality simultaneously.

Lean implementations make use of techniques such as Kaizen (continuous, incremental improvements). They also empower employees at all levels to identify problems and suggest solutions.

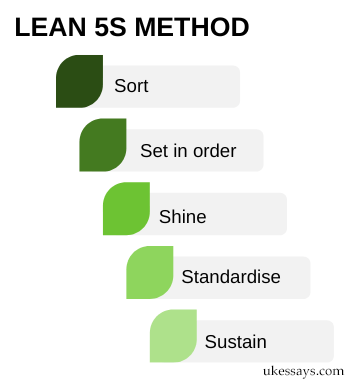

A lean workplace often applies the 5S method (Sort, Set in order, Shine, Standardise, Sustain) to organise and standardise the work environment. This practice reduces errors and delays.

Visual management and just-in-time scheduling (e.g. using Kanban boards) are also hallmarks of lean operations.

Ultimately, lean principles create a culture in which processes are continually reviewed and refined. Workflows become ever smoother and more responsive to customer needs. This cultural aspect of engaging and enabling people is as important as any technical tool in lean’s success.

Six Sigma principles

Six Sigma provides the complementary discipline to lean by focusing on variation reduction and robust quality control. It rests on the premise that reducing process variation results in fewer defects and more predictable outputs, which increases customer satisfaction.

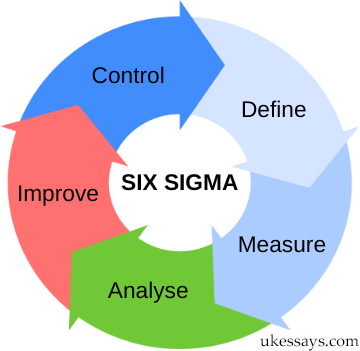

Six Sigma projects follow a structured problem-solving framework known as DMAIC – Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve, Control – to systematically improve existing processes.

In the Define phase, the team clearly defines the problem, project goals and customer requirements (often capturing the “voice of the customer”).

For Measure, they collect data on current performance and quantify the problem (for example, measuring baseline defect rates or process cycle times).

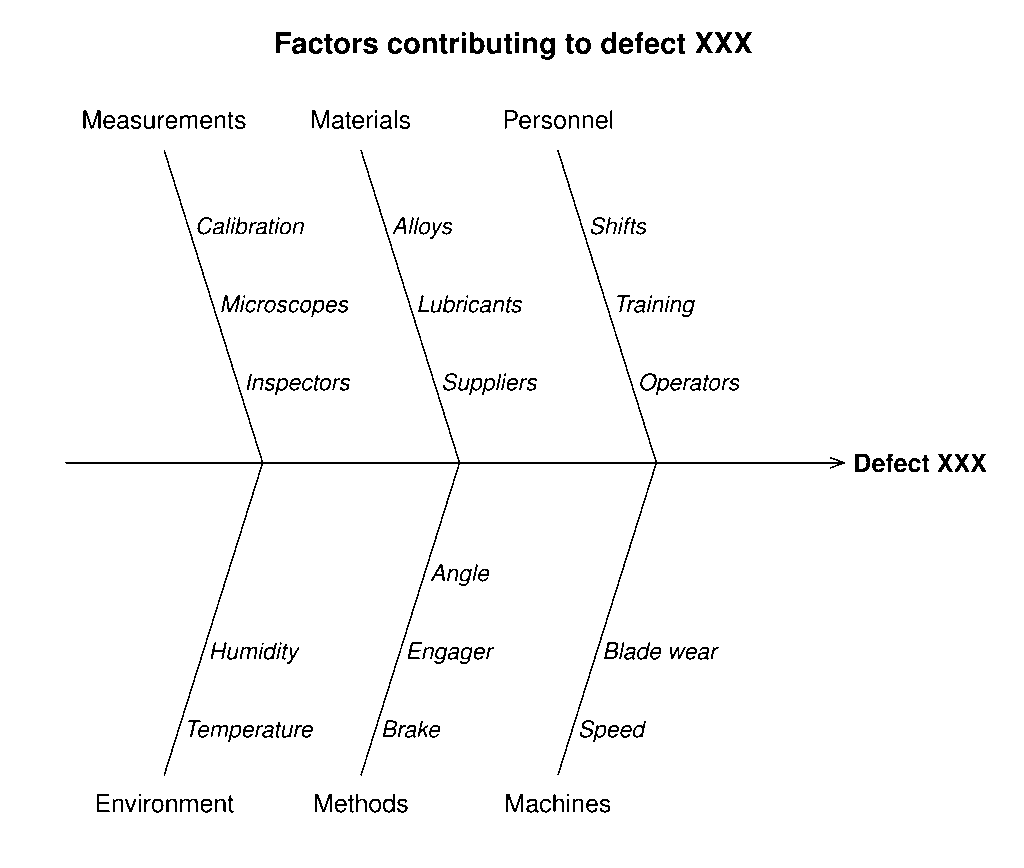

During the Analyse phase, the team uses statistical methods to identify root causes of the problem. They might employ tools such as cause-and-effect (fishbone) diagrams or hypothesis tests to pinpoint which factors are driving defects.

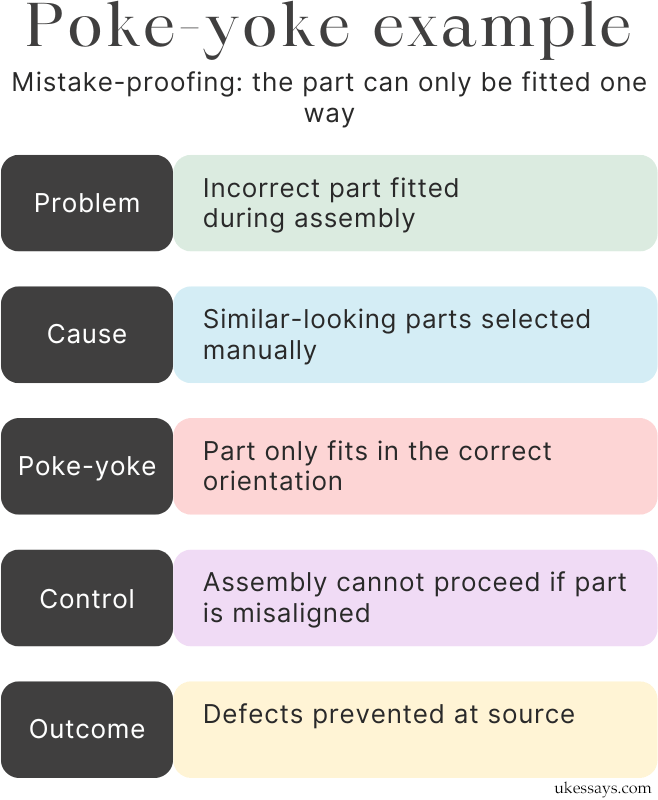

In Improve, the team develops and implements solutions to address the root causes. For example, they might redesign a problematic process step, introduce an error-proofing mechanism (poka-yoke), or eliminate a bottleneck. The improvements are then tested – often via pilot runs – to verify that they yield better outcomes.

In Control, the team establishes procedures and controls to sustain the gains. For instance, they may implement standard operating procedures, provide additional staff training, or introduce statistical control charts.

These steps prevent the process from reverting to its previous state.

A key aspect of Six Sigma is its emphasis on delivering measurable results tied to business objectives. Practitioners expect Six Sigma projects to produce quantifiable improvements (e.g., cost savings, shorter cycle time, defect reduction) that align with organisational goals.

Snee (2010) describes Lean Six Sigma as not just a set of tools, but a business strategy and methodology. It can increase process performance, boost customer satisfaction, and improve bottom-line results by continually enhancing quality and efficiency.

Lean Six Sigma methodology

In an integrated Lean Six Sigma deployment, lean and Six Sigma are woven together into a unified approach. In practice, most Lean Six Sigma initiatives use the DMAIC framework as the backbone for process improvement projects. At the same time, they infuse lean concepts into each phase of DMAIC. This combined approach ensures that both waste reduction and variability reduction are addressed in every project.

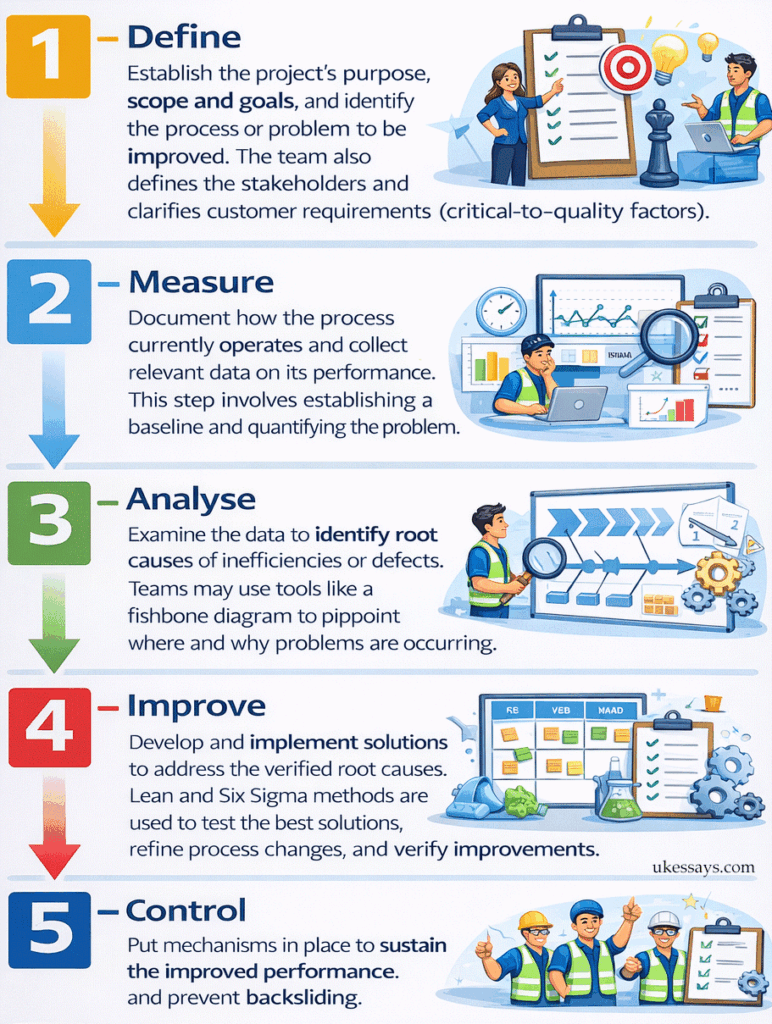

A typical Lean Six Sigma project proceeds through five key phases:

Define: Establish the project’s purpose, scope and goals, and identify the process or problem to be improved. The team also defines the stakeholders and clarifies customer requirements (critical-to-quality factors).

Measure: Document how the process currently operates and collect relevant data on its performance. This step involves establishing a baseline and quantifying the problem. For example, the team might measure how often defects occur or how long a process takes on average.

Analyse: Examine the data to identify root causes of inefficiencies or defects. The team may use tools like value stream maps, scatter plots, statistical tests or fishbone diagrams to pinpoint where and why problems are occurring. The analysis should validate theories with data, ensuring the team targets the true causes of issues.

Improve: Develop and implement solutions to address the verified root causes. This could involve removing unnecessary steps, rebalancing workloads, automating tasks, or other process changes.

Lean techniques (such as 5S or Kanban) are often introduced at this stage alongside Six Sigma techniques (such as error-proofing or design of experiments). Together, these methods help achieve optimal results. Solutions are often tested on a small scale (pilot) to confirm they lead to the desired improvements.

Control: Put mechanisms in place to sustain the improved performance and prevent backsliding. This typically includes updating standard operating procedures, training staff on new methods, and instituting ongoing monitoring (for instance, using control charts or dashboard metrics). The process owner is made responsible for maintaining the gains. The team also documents lessons learned and may conduct a hand-over to process owners along with a control plan.

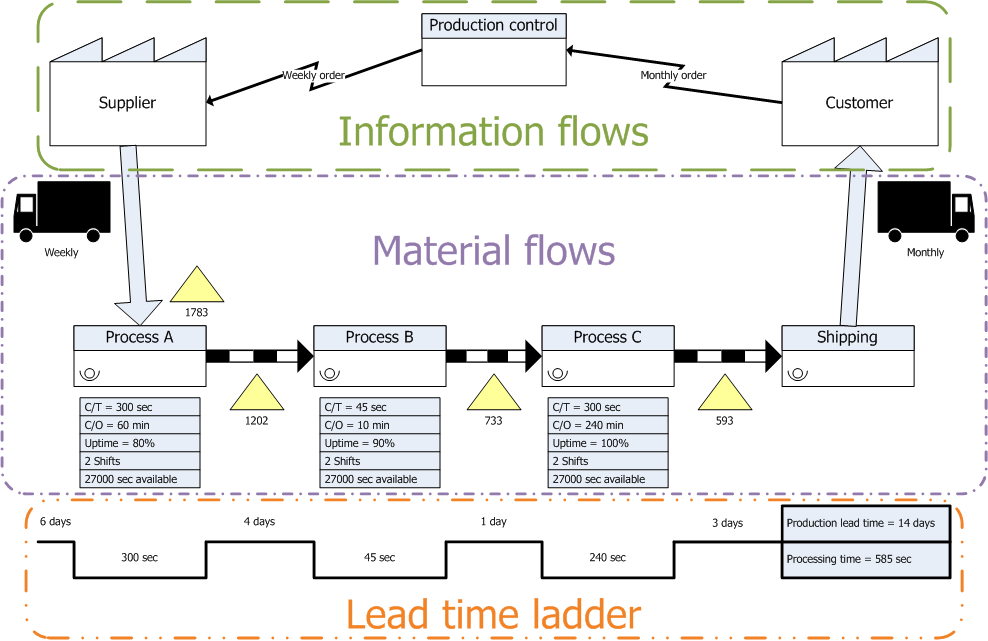

Throughout these phases, Lean Six Sigma teams apply a wide array of analytical and visual tools to facilitate problem-solving. For example, they may create a value stream map during Define or Measure to visualise all the steps in the process and highlight wasteful delays. Later, in the Analyse phase, statistical techniques like regression analysis or hypothesis testing can confirm which factors truly affect the process outcomes.

This blending of approaches is a hallmark of Lean Six Sigma. For example, a team might streamline a process flow using lean methods, while also refining process parameters for consistency with Six Sigma’s data analysis. Moreover, projects are typically chosen and prioritised based on strategic alignment and potential impact. Organisations tend to focus Lean Six Sigma efforts on high-impact areas where improvements will yield substantial benefits for the business and customers.

It is also worth noting that Lean Six Sigma can be applied not only to improve existing processes but also to design new processes or products. In the latter case, a variant methodology called DMADV (Define, Measure, Analyse, Design, Verify) – also known as Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) – is employed. DMADV follows similar principles to DMAIC but is geared toward developing processes that meet Six Sigma quality from the start.

By using Lean Six Sigma in the design stage, organisations can build quality and efficiency into a process before it ever goes into operation. This proactive approach prevents waste and defects from occurring in the first place.

Tools and techniques

Lean Six Sigma’s strength lies in its versatile toolkit, which encompasses methods from both the lean and Six Sigma traditions. Practitioners are trained to select appropriate tools depending on the problem at hand. For example:

Lean tools:

Methods such as 5S (workplace organisation), Kanban (a pull-system for workflow management), and value stream mapping (visualising process steps to identify waste) help expose inefficiencies and reduce cycle times.

Lean emphasises simple, visual techniques that engage teams in spotting and eliminating non-value-added activities.

Other lean techniques like poka-yoke (error-proofing mechanisms) and SMED (rapid changeover methods) further enhance quality and flexibility without requiring significant capital investment. Collectively, these tools enable processes to run faster, smoother and with less waste.

Six Sigma tools:

A variety of statistical and problem-solving tools from the Six Sigma repertoire are used to diagnose issues and control process quality. For instance, a fishbone diagram (Ishikawa cause-and-effect diagram) can systematically explore potential root causes of a defect. Pareto analysis (the 80/20 principle, i.e. roughly 80% of effects come from 20% of causes) can highlight the most frequent or costly problems to prioritise for action. Another core tool is Statistical Process Control (SPC), which uses control charts to monitor process stability over time and detect any undesirable variation.

Six Sigma also employs quantitative methods such as process capability analysis, Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) for proactive risk assessment, and Design of Experiments to optimise processes. Software like Minitab or JMP is often used for statistical data analysis. By grounding improvements in solid data, these tools ensure that changes are effective and that processes achieve the desired performance (often measured in sigma level).

Crucially, Lean Six Sigma does not require using every tool for every project – practitioners learn an arsenal of techniques and apply those that fit the situation. The integration of lean and Six Sigma tools means teams can tackle a problem from multiple angles. For example, they might employ a Kaizen blitz to quickly remove obvious waste in a process. At the same time, they could use statistical analysis to fine-tune process parameters for quality control. This flexibility is part of why Lean Six Sigma has proven effective across very different industries and business processes.

Roles and training

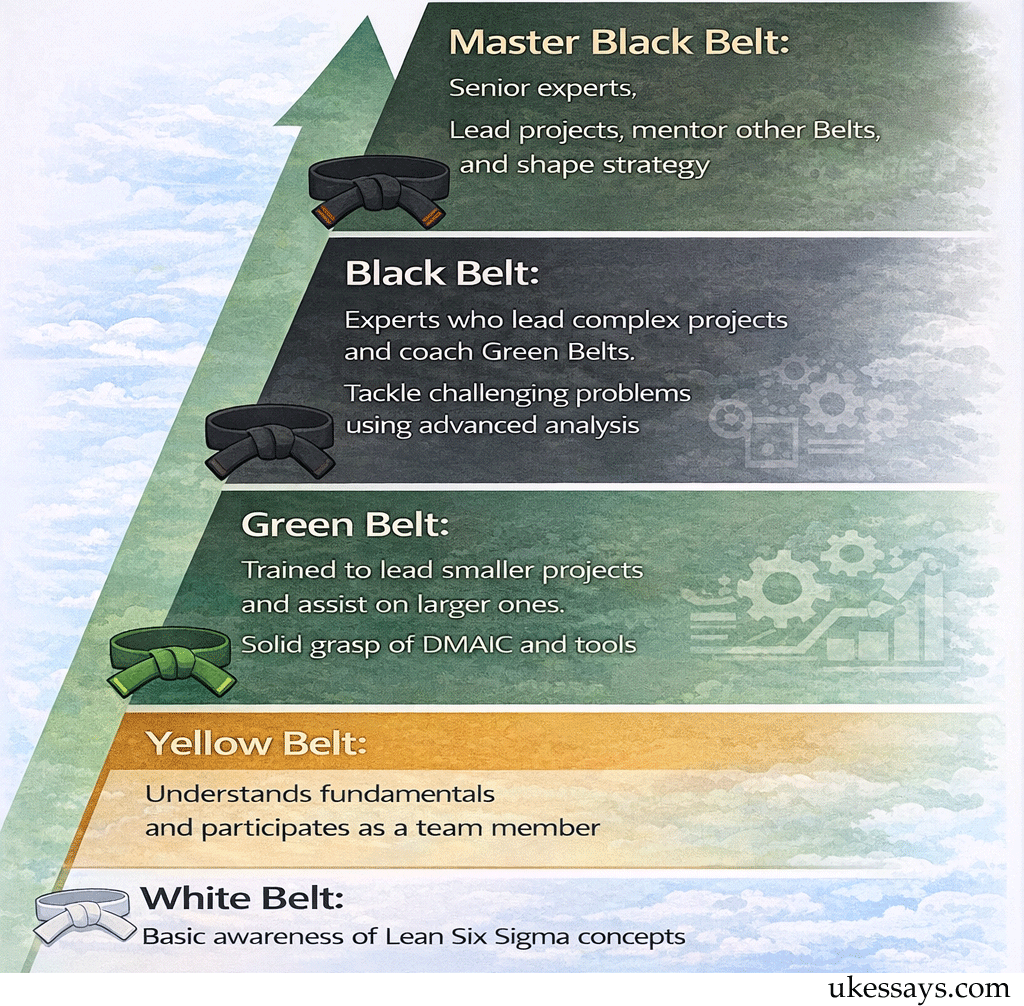

Successful Lean Six Sigma deployments rely on a structured roles system and extensive training to build in-house expertise. Borrowing terminology from martial arts, Six Sigma introduced “belt” certifications to denote levels of proficiency (Hayes 2025).

A White Belt typically has a basic awareness of Lean Six Sigma concepts. A Yellow Belt understands the fundamentals and participates in improvement projects as a team member. A Green Belt is trained to lead smaller-scale projects or assist on larger projects, possessing a solid grasp of the DMAIC methodology and tools. Black Belts are experts who lead complex or cross-functional projects full-time; they coach Green Belts and tackle challenging problems using advanced analysis. At the top, Master Black Belts are senior experts. They not only lead projects but also mentor other Belts and help shape the organisation’s continuous improvement strategy.

In addition to the belt hierarchy, organisations assign other key roles to facilitate Lean Six Sigma initiatives. Project Champions (or Sponsors) are typically senior managers who sponsor projects, ensure they align with business objectives, and remove obstacles for the team. Champions provide oversight and support to project teams and help drive accountability for results.

Another important role is the process owner, the individual responsible for the process being improved. The process owner works with the project team from the start and is accountable for sustaining the improvements after the project concludes.

Training is a critical element in Lean Six Sigma adoption. Employees typically undergo formal training programs (often provided by accredited organisations or internal experts) to earn belt certifications. These courses cover Lean Six Sigma principles, methods, and tools, and often include hands-on simulations or real project work.

For example, a Green Belt training might span several weeks and require the candidate to complete an actual improvement project. This ensures they demonstrate the use of the DMAIC approach in practice.

Investing in this human capital ensures that the organisation builds a cadre of problem-solvers equipped to drive improvements. Further, having a common methodology and terminology across the workforce – thanks to belt training – fosters better collaboration on cross-functional improvements. A shared Lean Six Sigma language ensures that cross-functional teams have a common understanding of the approach. An engineer, an operations manager, and a finance analyst can all contribute to the same project without miscommunication.

Benefits of Lean Six Sigma

When implemented effectively, Lean Six Sigma can yield substantial benefits for organisations in terms of performance, customer outcomes and financial results. By attacking both inefficiency and quality issues, Lean Six Sigma projects often produce faster processes with fewer errors, as measured by cycle time, defect rates, and first-pass yield. This directly lowers costs and enhances the value delivered to customers.

Indeed, companies have reported significant gains. For example, Motorola credited its Six Sigma initiatives with over $16 billion in cumulative savings over two decades of implementation. Moreover, countless case studies document the improvements achieved after Lean Six Sigma interventions (Pepper and Spedding 2010). These include reduced defect rates, shorter lead times, and higher customer satisfaction.

One primary benefit is cost reduction through efficiency gains. Eliminating wasteful steps and rework means processes consume fewer resources and less time. This translates into lower operating costs and higher productivity. For instance, if a bank uses Lean Six Sigma to streamline its loan approval process, it might cut out redundant checks and reduce errors. As a result, the bank can handle a higher volume of loans with the same staff, thereby reducing the cost per transaction.

Another key benefit is higher quality and consistency of outputs. With Six Sigma techniques reducing process variation, products and services have more predictable outcomes and meet specifications more reliably. This improves customer satisfaction, as customers receive defect-free products and timely, dependable service. In sectors like healthcare, achieving a higher process capability (for example, in medication administration or surgical instrument sterilisation) leads to safer patient outcomes.

Pepper and Spedding (2010) note that Lean Six Sigma’s flexible approach can simultaneously drive down costs and ensure quality at all levels of operations. This combination clearly strengthens overall business performance.

Lean Six Sigma also often leads to an improved customer experience and greater customer loyalty. By focusing on what the customer truly values, and by reducing the defects or delays that cause customer pain points, organisations can better meet (or even exceed) customer expectations. Faster delivery times, fewer mistakes, and more responsive service all contribute to a better experience.

Many firms apply Lean Six Sigma to improve metrics such as on-time delivery, first-pass yield or service response time. These indicators directly influence customer perceptions of reliability and quality, so improving them can boost satisfaction and retention.

In addition, there are important cultural and workforce benefits. Lean Six Sigma, when embraced as a continuous improvement culture, actively engages employees in problem-solving. Front-line staff are empowered to suggest improvements and to participate in project teams, which can increase their job satisfaction and morale. As processes improve, employees spend less time “fighting fires” or overcoming workarounds, and more time on value-adding work.

DeFeo (2024) observes that once Lean Six Sigma practices take root, employees naturally become more attuned to spotting waste and variation in their work. This heightened awareness reinforces a cycle of ongoing improvement in the organisation.

Lean Six Sigma also supports better strategic alignment and decision-making. Because it is data-driven and project-focused, it compels organisations to select improvement initiatives that have clear ties to strategic goals and to measure outcomes rigorously. Over time, this cultivates a fact-based culture of management. Resources for improvement get directed to projects with the highest impact, and performance metrics become more transparent.

In essence, Lean Six Sigma can act as a vehicle for executing strategy. Leadership sets objectives (such as improving customer retention or reducing manufacturing cost). Project teams then apply Lean Six Sigma methods to achieve these goals in measurable terms.

Implementation considerations and success factors

Despite its advantages, implementing Lean Six Sigma is not a trivial undertaking. Organisations often encounter challenges in sustaining the improvements and achieving the cultural shift required for long-term success. Research has identified several critical success factors that determine whether a Lean Six Sigma deployment truly takes hold (Laureani and Antony 2012). Key factors include:

Leadership commitment:

Strong, visible support from top management is essential. Leaders need to champion the Lean Six Sigma initiative, provide adequate resources, and hold teams accountable for results. Without executive buy-in, projects can falter or be deprioritised. Management should also model data-driven decision-making and continuous improvement in their own actions.

Strategic alignment:

Lean Six Sigma efforts should be closely aligned with the organisation’s strategic objectives and customer needs. Selecting the right projects – those that address important business goals – ensures that improvement work delivers meaningful value. A clear link to strategy also helps maintain focus and justifies the investment in training and project time.

Organisational culture and change management:

Adopting Lean Six Sigma often requires a cultural shift in which employees at all levels embrace continuous improvement and feel empowered to challenge the status quo. This can be fostered through open communication, recognition of project successes, and involving staff in improvement workshops.

It is important to address resistance to change by demonstrating early “quick wins” and by highlighting benefits to employees (e.g., making their jobs easier by removing frustrating obstacles). A collaborative culture that encourages teamwork and knowledge sharing will amplify the impact of Lean Six Sigma.

Training and expertise:

Building internal capability through training is critical. Successful organisations invest in developing a cadre of Green Belts and Black Belts with the skills to lead projects. They also educate a broader base of employees in Lean Six Sigma basics, so that quality improvement is widely understood.

Inexperienced teams might struggle to apply statistical tools correctly or to choose the right lean techniques. Therefore, mentoring by experts (such as Master Black Belts or external consultants) can be extremely valuable. When people have the proper training and guidance, they are far more effective at delivering project results.

Effective project selection and management:

Improvement projects should be well-chosen, scoped appropriately, and managed rigorously. Projects need clear definitions and manageable scope – tackling a moderate-size problem is more likely to succeed than an unbounded one. It also helps to establish a governance mechanism (such as a steering committee) to monitor project progress and remove roadblocks.

Integration with existing initiatives:

Lean Six Sigma should be coordinated with other business improvement programs (like Total Quality Management or ISO 9001). This integration ensures consistency and prevents initiative overload.

In a survey of companies by Laureani and Antony (2012), top management commitment, cultural change, and linking Lean Six Sigma to business strategy emerged as the most critical factors for effective implementation. On the other hand, some factors often assumed to be important turned out to be less critical in practice. For example, tying Six Sigma results to individual performance rewards or trying to extend the program to suppliers early did not strongly influence success.

This suggests that organisations should focus first on leadership, culture and strategic alignment when rolling out Lean Six Sigma. Indeed, many failed deployments can be traced back to neglecting these fundamentals. For example, a company might train a number of Green Belts but then fail to give them proper management support or time to work on projects. This situation typically results in little impact.

It is also important to acknowledge that Lean Six Sigma has its limitations and may not solve every problem. If not applied thoughtfully, it can lead to an excessive focus on metrics or a rigid, box-ticking approach to improvement.

Some critics have argued that an overly rigid Six Sigma program can stifle creativity. If practitioners become too preoccupied with strictly following DMAIC steps, or if the belt hierarchy discourages input from non-experts, innovative ideas might be lost. To mitigate this, successful implementations remain flexible. They use Lean Six Sigma as a guiding framework but still encourage creative thinking and adaptation to the organisation’s unique context.

Wrapping up:

Lean Six Sigma has proven to be a powerful methodology for organisations seeking continuous improvement in quality, efficiency and customer satisfaction. By uniting the principles of lean and Six Sigma, it addresses both waste and variability. This combined approach delivers a “one-two punch” to process problems that few other methodologies can match.

Over the past few decades, Lean Six Sigma has matured from its origins in manufacturing into a broad business improvement strategy. It is now employed by hospitals, banks, technology firms and many other organisations, demonstrating that its principles can apply wherever processes exist.

Crucially, the success of Lean Six Sigma depends not just on technical tools, but also on human and strategic factors. Companies that weave Lean Six Sigma into their culture – with strong leadership support, engaged employees, and alignment to strategic goals – tend to reap the most sustained benefits. By contrast, organisations that neglect these fundamentals may struggle to get results, even if they adopt the right techniques on paper.

As global competition and customer expectations continue to rise, approaches like Lean Six Sigma will remain highly relevant. Its blend of analytical rigour and practical teamwork equips organisations to meet these evolving challenges. The journey of continuous improvement is never truly finished. However, Lean Six Sigma provides businesses with the mindset and tools to keep advancing toward ever higher levels of performance.

Need help with a lean six sigma assignment or project? From case studies to improvement plans, our business assignment help service supports students at every belt level.

References and further reading:

- DeFeo, J.A. (2024). Lean & Six Sigma Training: A Definitive Guide. Juran OpEx Blog, 25 January 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://www.juran.com/blog/guide-to-lean-and-lean-six-sigma (Accessed 10 November 2025).

- George, M.L. (2002). Lean Six Sigma: Combining Six Sigma Quality with Lean Speed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hayes, A. (2025). What Is Six Sigma? Concept, Steps, Examples, and Certification. Investopedia, updated 2 October 2025. [Online]. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/six-sigma.asp (Accessed 10 November 2025).

- Laureani, A. and Antony, J. (2012). Critical success factors for the effective implementation of Lean Six Sigma. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 3(4), 274-283.

- Pepper, M.P.J. and Spedding, T.A. (2010). The evolution of Lean Six Sigma. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 27(2), 138-155.

- Snee, R.D. (2010). Lean Six Sigma – getting better all the time. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 1(1), 9-29.

- Womack, J.P. and Jones, D.T. (1996). Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: