Guide to writing law dissertations

Info: 7898 words (32 pages) Study Guides

Published: 13 Dec 2025

For expert guidance on writing law dissertations, our UK-qualified writers offer tailored academic support. Explore our law dissertation help page to find out more.

Writing a law dissertation is a challenging yet rewarding process. It involves conducting an in-depth independent legal research project on a topic of your choosing. The purpose is to demonstrate that you can engage in sustained independent study and produce work that is substantially your own.

In other words, you must take the initiative to identify a research question, gather and analyse legal sources, and present a well-argued analysis without relying on others to do the thinking for you.

Successfully completing a dissertation not only fulfils an academic requirement – it also allows you to develop a specialism in your chosen area of law. In the process, you gain valuable skills that can set you apart as a graduate (Kherbane 2015).

Understanding the purpose of a law dissertation

A law dissertation (sometimes called a legal research project) is typically undertaken in the final stages of a law degree. It may be an optional module in the final year of an undergraduate LL.B., a core requirement for a Master of Laws (LLM) degree, or an independent research project as part of a Legal Practice Course (LPC) or similar professional qualification.

In all cases, the fundamental goal is the same: to conduct independent legal research on a defined question or problem and communicate your findings in a clear, structured thesis.

Unlike ordinary coursework or exams, a dissertation is student-directed. You choose the topic, design the research, and carry it through from start to finish with guidance from a supervisor.

This exercise is intended to cultivate your ability to think critically, explore legal issues in depth, and manage a large project. It is also an opportunity to explore in detail an area of law you are passionate about beyond the constraints of the taught curriculum.

Writing a dissertation tests a range of skills that are crucial for legal professionals. It requires advanced research skills – a good lawyer is not expected to know all the law offhand, but rather to know where to find the law on a given issue. By working on a dissertation, you will learn how to efficiently locate and sift through case law, legislation and academic commentary on your topic (Kherbane 2015).

You also develop the ability to construct a sustained argument. Dissertations demand succinct arguments and the reduction of complex information into concise, logical writing (Kherbane 2015).

Furthermore, the project builds self-discipline and project management skills, as you must plan your work and meet deadlines with relatively little oversight.

In the process, you effectively learn how to “think like a lawyer”. That means identifying relevant facts and legal questions, reviewing what others have said about them, and then formulating your own reasoned conclusions. These are qualities that will serve you well whether you go into legal practice or academic research.

Types of law dissertations: undergraduate, LLM and LPC projects

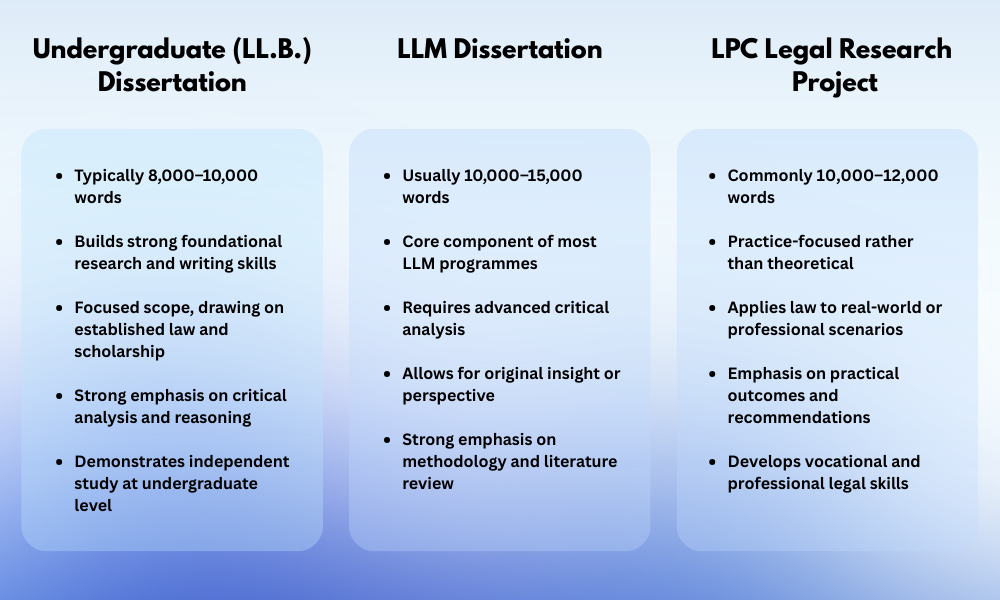

Law dissertations can arise at different levels of study, and the expectations may vary between an undergraduate project, an LLM thesis and an LPC research project. It is helpful to understand the context and requirements of each:

Undergraduate law dissertations

At the undergraduate level (LL.B.), a dissertation is often an optional module in the final year, though some universities make it compulsory. An undergraduate law dissertation is typically 8,000–10,000 words in length.

The goal is to allow students to delve into a legal topic of their choice and showcase skills in research, critical analysis and written argument. Because undergraduates are new to this kind of independent research, the scope of an LL.B. dissertation is usually narrower and more focused on synthesising existing knowledge rather than breaking entirely new ground.

You are expected to demonstrate that you can formulate a clear research question, engage deeply with primary and secondary legal sources, and present a coherent analysis. For example, you might examine a controversial court decision or compare how a particular law operates in two jurisdictions.

Completing a dissertation at this stage is an excellent way to explore an area of law that interests you beyond the core curriculum. It can also highlight to employers or postgraduate admissions that you have a genuine enthusiasm and aptitude for legal research.

LLM dissertations

In a taught postgraduate law degree (LLM), the dissertation is usually a core component and often the capstone of the program. LLM dissertations are expected to be more advanced in analysis than undergraduate ones. They are often around 10,000–15,000 words in length, depending on the university’s requirements (Kherbane 2015).

At Master’s level, you are expected to engage critically with your topic and perhaps provide some original insight or perspective. The dissertation allows you to study a specific field of law in depth – far beyond what is covered in classes – and to contribute to discussions in that field.

For instance, an LLM student might undertake a comparative analysis of data protection laws, or a critical evaluation of an emerging issue in international law. Because this is a higher qualification, there is a strong emphasis on rigorous methodology and a thorough literature review. Your arguments should reflect a deep understanding of the theoretical frameworks or policy debates relevant to the topic.

The LLM dissertation demonstrates your “intellectual drive and dedication” to explore a legal issue independently (Taylor 2021). In practical terms, it proves you can produce a substantial piece of academic legal writing to a professional standard. This is a skill that is valuable for careers in academia, policy or specialised legal practice.

LPC legal research projects

If you are pursuing the Legal Practice Course (LPC) – now often taken alongside a Master’s in Legal Practice – you may have to complete an independent legal research project as part of that program.

An LPC research project serves a purpose analogous to a dissertation, but it tends to be practice-oriented. The focus is often on applying law to real-world scenarios or current legal issues in practice, rather than purely theoretical inquiry. For example, you might research how a recent regulatory change impacts solicitors’ professional responsibilities, or propose improvements to a practical aspect of commercial law procedure.

The target length can be similar to an LLM dissertation (commonly around 10,000–12,000 words, depending on the institution). However, the key difference lies in the approach. The LPC project emphasises vocational skills and the practical application of the law (Taylor 2021). This means your research might culminate in something like a detailed advice to a (hypothetical) client, a proposal for law reform, or an evaluation of how effectively the law achieves certain policy objectives.

You will still need to perform rigorous research and analysis, but you are expected to keep an eye on practical outcomes and recommendations. In some combined LPC/LLM programmes, completing the research project can earn you a Master’s degree in addition to the LPC, demonstrating both practical training and academic research ability (The Lawyer Portal 2025).

Overall, whether at LL.B., LLM or LPC level, the dissertation or research project is an exercise in independent learning and a chance to hone your expertise in a particular legal subject.

Choosing a research topic

One of the first and most important steps is choosing a suitable topic for your law dissertation. This decision will shape your entire project, so it’s worth investing time and thought at the outset.

A good dissertation topic is interesting, original and feasible. Since you will be spending many months on this research, you should pick a subject that genuinely engages you. Passion for the topic will keep you motivated and will shine through in the quality of your work.

Moreover, you are likely to produce better analysis if you care about the questions you are investigating (Queen Mary University of London 2024).

Refining your research question

Be guided by your intellectual curiosities. For example, you might choose a topic that emerged from a course that fascinated you. Alternatively, a pressing legal controversy you encountered in the news could spark your research question.

When refining your topic, aim for a scope that is narrow enough to be manageable but broad enough to find sufficient research material.

It is a common mistake to start with an overly broad idea. Instead, try to identify a specific legal question or a precise problem within a wider area. For instance, “human rights law” is far too broad, but “the impact of UK surveillance laws on the right to privacy under the ECHR since 2016” is specific and focused. Ensure that your research question is also academically significant – it should not be trivial or purely descriptive.

Ask yourself: is this an issue that raises debate or uncertainty in the law? Does it have practical, theoretical or social importance? If the answer is yes, then it likely has the substance needed for a good dissertation (Queen Mary University of London 2024).

On the other hand, a question like “whether Shakespeare used the word ‘and’ more often in his comedies than in his tragedies” might be answerable. However, it would not be meaningful to a wider audience (Queen Mary University of London 2024).

Ensuring feasibility and academic value

It’s also crucial to check the availability of sources on your prospective topic. Before committing, do some preliminary research to ensure there is enough material (cases, statutes, journal articles, data, etc.) to support your work.

If you discover that key information is inaccessible or that very little has been written on your chosen issue, you may need to rethink or refine the scope. A dissertation topic is only viable if you can gather adequate evidence and authorities to examine it properly (Queen Mary University of London 2024).

In short, balance ambition with pragmatism. Choose a topic that excites you, but also one you can realistically research with the time and resources available.

Common sources of law dissertation topics

To generate ideas, it can be helpful to survey recent developments in law and society. Pay attention to new legislation, high-profile court cases or legal debates in the media – these can all spark interesting research questions (Moffatt 2020).

University coursework or internships might have exposed you to unresolved issues that you could explore further. Be creative and look for an angle that stands out. Often, strong dissertation topics fall into one of a few categories, for example:

- Controversial issues or reforms: e.g. examining the legal implications of a recent contentious bill or Supreme Court decision.

- Unsettled questions in case law or statute: e.g. analysing a point of law where courts or commentators disagree on the interpretation.

- Gaps or inconsistencies in the law: e.g. identifying areas where the law is conflicting, outdated or does not effectively achieve its purpose.

- Comparative or international perspectives: e.g. comparing how different jurisdictions tackle the same legal problem, and what each can learn from the other.

These are just illustrative categories – a good topic can come from anywhere as long as it meets the criteria of interest, significance and feasibility. Discuss your ideas early with faculty or with your assigned supervisor (if you have one). Get feedback on the scope and suitability of your chosen topic.

Research proposal and planning

Many law programs require students to submit a research proposal before embarking on the full dissertation. Even if it’s not mandatory in your case, writing a proposal is highly recommended.

A research proposal is essentially a blueprint of your project: it outlines what you intend to study and how you plan to do it.

Typically, a proposal will include several elements: a provisional title or research question, an introduction explaining the context and importance of the topic, and a brief literature review to show your awareness of key writings on the subject (Essays UK 2018). It will also outline your proposed research methodology or approach, and provide a plan or timeline for completing the work.

Defining aims and objectives

In a proposal you should also have clearly stated aims and objectives – what questions will you answer, or what argument will you advance? The more detailed and concrete your proposal, the more useful feedback you are likely to receive from your supervisor or proposal reviewers (LawTeacher 2018).

Crafting the proposal forces you to clarify your thinking at an early stage, which can save you from floundering later on. It’s much better to discover early if a project is unfeasible or too broad. You do not want to find that out when you are already halfway through writing it (Moffatt 2020).

Final checks

Before finalising your proposal, make sure it meets your law school’s requirements (word count, format, any specific sections required) and then take advantage of any feedback.

Your supervisor might point out, for example, that you need to narrow your question further, or suggest additional sources you hadn’t considered. Use that input to refine your plan.

Once the proposal is approved, it serves as a roadmap for your dissertation. Refer back to it to stay on track, but remain flexible because research can evolve as you discover new information.

Building a dissertation timeline

Planning and time management are critical in a research project of this scale. It is often said that you should spend as much time planning your dissertation as writing it.

At the very beginning, draw up a rough timetable from now until your submission deadline. Identify major milestones and target dates for each (for example: “complete initial literature review by [date]”, “finish data collection by [date]”, “draft Chapter 1 by [date]” and so on). Mark your final deadline clearly and work backwards to allocate time for each phase.

One academic advisor emphasises that getting yourself organised early – right now – by mapping out a plan is perhaps the single most important step to make the dissertation process as stress-free as possible (Moffatt 2020). Think about what you need to do and break it into smaller tasks. Then assign those tasks to weeks or months in your calendar.

Diarising deadlines

As you plan, be realistic about how long each part of the work might take. It’s better to give yourself some buffer time than to assume everything will go perfectly. Also build in time for unexpected delays – for instance, difficulty obtaining a source or waiting for feedback.

Critically, immediately diarise all key dates. If your department has interim deadlines (such as submitting a draft or a progress report), note those, as well as meetings with your supervisor and, of course, the final submission date (Moffatt 2020). Set reminders a week or two before each important date to prompt you to prepare.

Many students find it helpful to impose personal deadlines too, even if the university doesn’t. For example, set a date by which you aim to have a full first draft. A common piece of advice is to try to finish writing your dissertation at least two weeks before the actual due date (Moffatt 2020). By doing so, you leave yourself a cushion for revising and dealing with any last-minute issues, rather than scrambling up to the deadline.

Conducting legal research

Once your topic and plan are set, the next phase is extensive research. This will likely be the most time-consuming part of your dissertation journey.

Start with a thorough literature review. A literature review entails identifying, reading and synthesising all the relevant literature on your topic. In law, this includes primary sources (cases, statutes, regulations, treaties) as well as secondary sources (textbooks, journal articles, reports and commentary by legal scholars).

Aim to get a comprehensive view of what is already known and said about your research question (Queen Mary University of London 2024). This process helps you understand the current state of the debate and locate where your dissertation can contribute.

Make sure you engage critically with the material – don’t just passively read. Take notes on key points, and note any disagreements or gaps you observe in the existing scholarship.

Engaging critically with different viewpoints

It’s important to cast your net wide and not cherry-pick only sources that support your argument. A good researcher considers all sides of an issue.

As you review the literature, include differing viewpoints and contrary arguments, and be prepared to address them in your dissertation. Demonstrating that you have examined all relevant material – not just the authorities that back up your hypothesis – will strengthen your analysis (Queen Mary University of London 2024).

For example, if some authors argue one interpretation and others disagree, acknowledge that debate and explain which view you find more convincing and why. Being honest about the complexity of the issue shows academic maturity. It also prevents you from ignoring a key source that an examiner will expect you to know about.

Using legal research tools and managing sources

In practical terms, you should make use of the legal research tools and resources available to you.

University law libraries (including online databases like Westlaw, LexisNexis, HeinOnline, etc.) are treasure troves for finding cases, legislation and journal articles. Take advantage of library research training sessions or guides – knowing how to efficiently search case law or academic journals will save you endless time.

Consider also less traditional sources where relevant: for example, official statistics, NGO reports or interviews (if you are doing field research).

Keep organised records of what you read. It’s often useful to maintain an annotated bibliography or a research log. This can be as simple as a document or spreadsheet where you list each source and jot down its key points and how it might fit into your dissertation. Not only does this keep you organised, it will also make citation easier later on (because you’ll have all the details of each source at hand).

Choosing and justifying a research methodology

As you deepen your research, be mindful of your research methodology – essentially, the approach you are taking to answer your question.

In law dissertations, a common methodology is doctrinal research, sometimes called the “black-letter law” approach, which involves close analysis of legal texts (cases, statutes) to ascertain what the law is and to reason about it.

Many dissertations are largely doctrinal, especially if they aim to clarify an area of law or analyse how legal principles apply. However, there are other methodologies that might suit your project. Comparative legal research might compare how different jurisdictions handle a problem. Historical methodology might trace how a legal doctrine developed over time.

In addition, some legal dissertations incorporate empirical research – for example, surveying public attitudes to a law, interviewing practitioners or analysing datasets on how a law is implemented. Empirical methods bring in tools from social sciences (like questionnaires, statistical analysis or case studies) to study the law’s impact in the real world.

If you choose an empirical or socio-legal approach, you will need to plan for research ethics approval and methodological rigor in collecting and analysing data (Lammasniemi 2021).

The key is that you must identify and justify your methodology in the dissertation. Explain briefly why your approach (be it doctrinal, empirical, comparative, etc.) is appropriate for answering your research question. Outlining the methodology shows the reader that you approached your study systematically and understand the limits of your methods.

Staying focused as your research evolves

Throughout the research phase, keep aligning what you find with your evolving thesis. Research is not a linear process – you might discover new pieces of information that make you adjust your focus or even rethink your argument. That’s normal. It’s often a dialectical process where your understanding deepens and your ideas refine as you engage with sources.

Just remember to periodically step back and ask: Is this information helping to answer my research question? If you find yourself going down a rabbit hole that’s only tangentially related, make a note of it. It might be useful background information. However, you should stay focused on the core issues to avoid wasted effort.

Structuring the dissertation

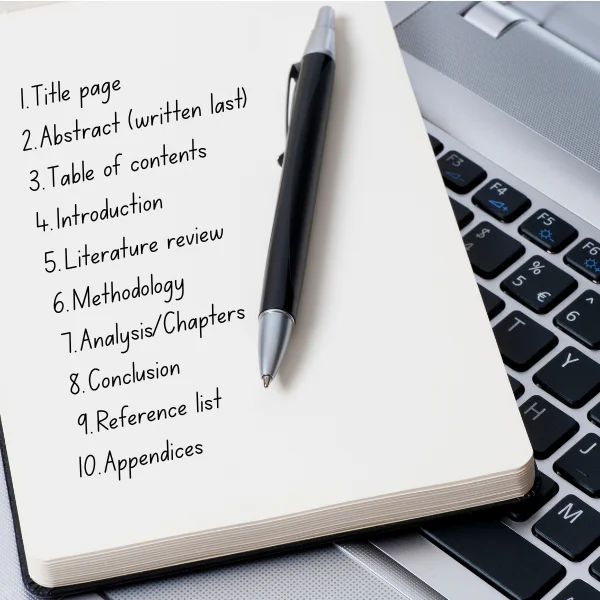

Early on, you should develop an outline for the structure of your dissertation. A clear structure is vital to guide the reader through your argument and to ensure you cover all necessary elements. See my guide to dissertation structure here.

Most law dissertations follow a conventional structure, which can be summarised as follows:

Title page

The cover page with your dissertation title, your name, student ID, degree program and the submission date. Your university may have specific format requirements for this.

Abstract

A short summary (usually around 200–300 words) of the dissertation. It should state the research question, outline the methodology and summarise the main conclusions. Although the abstract appears first, it is often written last.

Table of contents

A list of chapters and subheadings with page numbers to help readers navigate your document. You might also include lists of any tables or figures and a list of abbreviations, if relevant.

Introduction

The opening chapter introduces the topic and sets the stage. Here you explain the background and context of your research and state the central research question or hypothesis.

You should also outline your aims and objectives, and possibly give a brief overview of how the dissertation is structured.

By the end of the introduction, the reader should understand exactly what question you are investigating and why it matters.

An introduction is usually about 8-10% of the total word count, so in a 10,000-word dissertation it might be around 1,000 words (UKDiss, 2025).

Literature Review

This chapter surveys the existing literature and situates your research in relation to it. You summarise and analyse key sources (theories, case law, academic opinions) that are relevant to your question.

The literature review not only demonstrates the depth of your reading but also identifies gaps or debates your dissertation will address.

In some law dissertations, especially those that are purely doctrinal, the literature review may be integrated into the introduction or spread across the substantive chapters rather than a standalone chapter. But as a process, you will definitely conduct a literature review even if it’s not labeled as such in the final write-up.

Methodology

A chapter (or section) describing the research methods you adopted.

If your approach is doctrinal, you might describe how you selected and analysed sources (for instance, focusing on case law of a certain court and period).

If you did empirical research, here you would detail your research design: how you gathered data, your sample, what analytical tools you used and any ethical considerations.

For interdisciplinary work, you might also discuss theoretical frameworks here.

The methodology section justifies that your approach is sound and enables readers to understand how you obtained your results.

Analysis/Chapters

The main body of your dissertation will consist of one or more analysis chapters (the exact number and division will depend on your topic). This is where you present your findings or arguments in detail.

You might split the body into thematic chapters or perhaps chronological ones, depending on what makes sense for your argument. For example, in a 10,000-word dissertation you might have two or three substantive chapters, each focusing on a major aspect of the overall question.

Throughout these chapters, ensure that you maintain a clear line of argument. Start each chapter with an introduction to that section’s purpose, and end with a mini-conclusion summing up how it has advanced your overall thesis. Use headings and sub-headings to signpost the structure of your argument for the reader.

Conclusion

The final chapter draws together your findings and states the overall conclusion to your research question. This is not the place to introduce new evidence or arguments, but rather to synthesise what has been discussed in previous chapters and to answer the question posed in the introduction.

You should also reflect on the implications of your findings – for instance, you might suggest areas for further research or comment on the state of the law. Some dissertations include recommendations (especially if it’s a policy or practice-oriented topic) on how the law or problem should be addressed going forward.

The conclusion should give the reader a sense of closure and a clear understanding of what has been learned.

Reference list / Bibliography

A complete list of all sources cited in the dissertation, formatted according to the required referencing style. In law, this typically includes cases, statutes, books, journal articles and possibly websites or reports.

Some universities ask for a bibliography that also includes sources consulted but not explicitly cited. Be meticulous in compiling this list and following the style guide.

Appendices

An optional section for any supplementary material too bulky to include in the main text, such as interview questionnaires, extensive datasets or copies of documents.

Appendices usually do not count towards the word limit and should only include reference material that adds to your dissertation (not essential analysis).

Adjusting the structure to your project

This structure can be adjusted to fit your project. For instance, an empirical dissertation might have a separate “Results” chapter before a discussion, while a purely theoretical one might merge the literature review with the analysis.

Always follow any specific structure guidelines given by your law school in the dissertation handbook. Within this framework, ensure that the structure follows the logical flow of your argument (Queen Mary University of London 2024).

Each part of the dissertation should connect to your overall thesis, maintaining focus and coherence. If a section doesn’t clearly tie in, reconsider why it’s there. As you write, you might find you need to rearrange sections or chapters – that’s a normal part of refining the structure.

The ultimate goal is a well-organised dissertation where a reader can easily follow your reasoning from the introduction through to the conclusion.

Writing style and referencing

Writing a law dissertation requires a formal and clear academic style. Strive to write in the active voice and with clarity. Avoid long, unwieldy sentences – it is often better to express complex ideas in a series of precise, shorter sentences than one convoluted paragraph. Make sure each paragraph sticks to one main idea or point.

Transition words (such as “furthermore”, “however”, “for example”, “therefore”) are very useful to guide the reader and show how your ideas interrelate. A well-written dissertation will flow logically, almost like telling a story – albeit a scholarly and evidence-backed story – about your chosen legal issue.

Remember that clarity and precision are vital in legal writing. Define key terms, and don’t assume the reader has specialised knowledge of obscure points (examiners may not be experts in your exact topic). If your dissertation uses a lot of abbreviations or technical terminology, consider including a glossary or list of abbreviations for reference.

Throughout your writing, support every significant statement with evidence or reasoning. In legal analysis, this often means citing a case, statute or academic opinion to back up what you say. For example, if you assert that “the current law on X is inconsistent,” the reader will expect you to cite authorities or examples illustrating that inconsistency.

Writing concisely and structuring your argument

One hallmark of writing a good law dissertation is the ability to be succinct. Lawyers value conciseness – judges and senior partners don’t have time for waffle, and neither do dissertation examiners. Work on eliminating unnecessary filler words and getting to the point.

As one commentator notes, writing a dissertation teaches you to make succinct arguments and distill complex information into concise sentences (Kherbane 2015). This skill is extremely useful when drafting legal briefs or advising clients, where clarity and brevity are at a premium. However, being succinct does not mean being superficial. Your writing should still thoroughly explain your reasoning and engage with nuance where necessary, but without going off on tangents.

Using an appropriate tone is also important. Academic writing in law should be objective and measured. Avoid overly emotional language or bias. You can and should present a viewpoint or argument, but do so in a reasoned way, considering counterarguments.

Phrases like “it is submitted that…” can introduce your analysis in a formal, respectful tone. Also, write in British English if you are studying at a UK institution (e.g. use “organisation” instead of “organization”, and follow UK spelling and punctuation conventions).

Another key aspect is organisation. Use headings and sub-headings to break up the text and signal your structure. Each chapter should have a clear title, and longer chapters can be divided into sections with descriptive sub-headings. This not only helps the reader, but also helps you stay on track while writing. Numbering your sections (if allowed) can be useful for cross-referencing later.

Good organisation in writing is akin to presenting a legal argument in court – it should be easy for the audience to follow the progression of points. In fact, compiling a dissertation with contents pages, chapters and appendices is a bit like preparing a legal bundle or brief. This is a skill directly transferable to legal practice (Kherbane 2015).

Referencing and citation in law dissertations

Referencing deserves special attention when writing a law dissertation. Proper citation of sources is absolutely non-negotiable in academic work. Failing to cite sources correctly can expose you to allegations of plagiarism, which universities treat very seriously. From the start, keep track of all sources you consult and note down all bibliographic details (author, title, year, publisher, etc., or case name and citation for legal sources). This will save you a frantic scramble at the end to compile references.

Law schools typically specify which citation style to use. Many UK law faculties prefer the OSCOLA system (Oxford Standard for Citation of Legal Authorities), which uses footnotes for references to cases, legislation and literature. Others might allow or require an author-date style like Harvard.

Always check your dissertation handbook or ask your supervisor which referencing style is required, and then stick to it meticulously. For instance, OSCOLA style uses footnotes and a bibliography with specific conventions for different sources (cases, statutes, journals, etc.), whereas Harvard style uses in-text citations (author, year) and an alphabetical reference list at the end.

Each style has detailed rules, so familiarise yourself with the appropriate guide provided by your university.

Make sure you apply formatting consistently. For example, if case names should be italicised, do that every time. If ibid. is used for repeat citations in footnotes, use it correctly.

Beyond avoiding plagiarism, solid referencing has another benefit: it lends credibility to your work. When you back up a point with a citation to a respected journal article or a landmark case, you show the reader that your argument has grounding in established authority. It demonstrates the breadth and depth of your research.

As a practical tip, add citations as you write rather than leaving all referencing to the end. This ensures you don’t lose track of sources and saves time later. If you quote directly from any source, use quotation marks and cite the source with a page reference. If you paraphrase or summarise someone’s idea, cite them as well (without quotation marks). Every assertion of fact or law that is not common knowledge should have a reference.

Working with your supervisor

During your dissertation journey, your supervisor will be an invaluable resource. Most institutions assign each student a faculty supervisor – typically a professor or lecturer knowledgeable in your general area of research – to provide guidance and feedback. It’s important to understand how best to use this relationship. Remember, while the supervisor is there to help, the dissertation is ultimately your independent project.

In the early stages, schedule a meeting with your supervisor to discuss your topic and proposal. Come to the first meeting well-prepared – have an outline of your idea, some preliminary research, and questions to ask. The first discussion can significantly influence the direction of your entire dissertation, so you want to make a good start (LawTeacher 2018).

Don’t be afraid to raise any uncertainties about your topic’s scope or to ask for suggestions on sources – supervisors have overseen many dissertations and can often spot issues or opportunities that you might not. Additionally, use this opportunity to clarify mutual expectations. For example, discuss how often you should meet, in what format you will submit drafts, and what kind of feedback you can expect.

Used effectively, supervision can sharpen your thinking and keep your project on track, while still preserving the independence required when writing a law dissertation.

Managing feedback and expectations

Throughout the process, maintain a professional and proactive approach with your supervisor. Regular communication is key. If you have agreed to deadlines (for example, to produce a chapter draft by a certain date), do your best to meet them or inform your supervisor in advance if you need to adjust. Supervisors understand that things can evolve, but you will get more constructive feedback if you provide material in a timely manner.

When you do receive feedback, try not to take critique personally. Supervisors might make extensive comments or point out weaknesses in your draft – this is intended to help you improve your work. Engage with their suggestions: if they indicate that your argument in Chapter 2 is unclear, revisit it and consider how to clarify or strengthen it.

That said, a supervisor won’t usually tell you exactly how to rewrite a section. They will highlight problems, but it’s up to you to solve them, which is part of demonstrating independent thinking (LawTeacher 2018). A good student-supervisor dynamic is one where you seek discussion and advice, rather than simply asking “What shall I do next?” at every turn (LawTeacher 2018).

Supervisors are there to guide your independent study, not to micromanage it. They will expect you to take ownership of your project as it progresses. For example, instead of asking “I don’t know how to structure my argument, please tell me what to do,” you could draft a proposed structure yourself. Then you might ask for your supervisor’s opinion on it – for instance, whether they see any gaps or issues with your plan.

Another important tip is to ask specific questions to focus your supervisor’s feedback. For example, you might ask, “Do you think my analysis of the case law in Chapter 2 is sufficient?” or “Is the scope of my question appropriate?” This approach is often more productive than simply expecting general comments.

Also, be mindful of your supervisor’s availability. It’s wise to find out early on how often they can meet or review work, and what their preferred communication method is (email, office hours, etc.). If you hit a serious obstacle or crisis between scheduled meetings, most supervisors will try to help if you reach out. However, they are busy people, so only flag urgent issues that truly cannot wait (Moffatt 2020).

Finally, remember that while a dissertation is an academic endeavour, it can also be a chance to build a professional connection. If you show enthusiasm, diligence and receptiveness to feedback, you might impress your supervisor – who could later serve as a reference for jobs or further study.

Indeed, a good working relationship with your supervisor can lead to opportunities beyond the dissertation itself. Some students have gotten involved in research projects, received invitations to events or other networking opportunities through their supervisors (Kherbane 2015).

It goes without saying: always be respectful of your supervisor’s time. Prepare an agenda for meetings, be punctual and keep communications (like emails) clear and concise. In sum, use your supervisor’s expertise, but continue to own your dissertation. They are there to guide you, not to do the work for you.

Time management and work process

Managing your time effectively is crucial when undertaking a law dissertation. Unlike a regular assignment that might be due in a few weeks, a dissertation unfolds over many months, which can lull some students into procrastination. Don’t let the extended timeline lead to complacency. The most successful dissertation writers are those who work consistently and stick to a plan.

As mentioned earlier, start by creating a project timeline that breaks the work into stages. It helps to treat your dissertation like a part-time job or a regular class: dedicate specific hours each week to it, and increase that commitment as deadlines approach.

Begin working on your dissertation early – far earlier than you think you need to. Research suggests that students who start early feel less stressed and produce better work. Paula Moffatt (2020) advises that organising yourself from the outset and drawing up a plan “now” is vital for a smoother experience.

In practical terms, this means that as soon as your proposal is approved (or even before that if possible), you should get going with your reading and research. Even if your final deadline is a year away, what you do in the first few months sets the foundation. You could aim to finish your background reading and literature review in the first third of the time, so that you have a strong base for your own analysis.

Use interim deadlines to keep yourself on track. If your department doesn’t provide them (some do, such as a deadline for a literature review or a draft submission), set your own. For instance, commit to writing 1,000 words by the end of the month, or completing a particular chapter draft by a certain date.

Write these targets down and monitor your progress – it can be motivating to tick off milestones. Moreover, keep a careful calendar of any fixed deadlines: topic confirmation, proposal submission, draft submissions, final submission, etc. Set reminders for each a week or two in advance (Moffatt 2020). This way nothing sneaks up on you.

Expect that your progress might not be perfectly linear – sometimes research or writing will take longer than anticipated and you may need to adjust your schedule. That’s fine as long as you keep moving forward.

If you hit a snag (for example, difficulty analysing a particular concept or trouble obtaining a source), don’t freeze up. You can temporarily switch to another task (say, working on a different chapter or doing some editing on what you’ve already written) and then come back to the troublesome part fresh. Just avoid the trap of doing nothing on the dissertation for weeks because you’re stuck on one issue.

Avoiding last-minute pressure

Avoid last-minute cramming. A dissertation cannot be done in a few days or even a few weeks of all-nighters – it’s too much work, and the quality will suffer.

Give yourself the gift of time. Aim to have a full draft of your dissertation well before the actual deadline. In fact, having a complete draft a month early is ideal, but at minimum try to finish at least two weeks before (Moffatt 2020). That might sound overly cautious, but completing a full draft early means you can spend the remaining time refining and polishing it (which often elevates a piece of work from good to excellent). It also insulates you from disasters – if you fall ill or your computer crashes at the last minute, you have time to recover or resolve the issue.

Keep in mind that alongside your dissertation you may have other commitments (courses, exams, work, personal life). Balancing these requires discipline. Treat your dissertation tasks with the same importance as other deadlines by allocating dedicated time.

Some students set aside certain days or half-days every week solely for the dissertation. During those times, eliminate distractions and focus, as if you were in a class or an important meeting. Over the long run, consistent incremental work beats sporadic bursts of panic-fuelled writing.

It’s also important to take care of yourself during this marathon of research and writing. Working efficiently doesn’t mean working every single waking hour. In fact, taking regular short breaks can improve your productivity.

If you’ve spent an entire day reading cases, give your mind a rest in the evening. If you meet a major milestone, reward yourself in some small way. Maintaining a healthy study-life balance will keep you from burning out before the finish line.

Editing and proofreading

The final stage of producing your law dissertation – editing, revising and proofreading – is where you polish your work to the highest standard.

Do not underestimate the importance of thorough editing. A brilliantly researched dissertation can be undermined by poor structure, unclear writing or grammatical errors. Conversely, a well-edited dissertation can make even a modest analysis shine by presenting it clearly and logically.

Reviewing structure and overall coherence

Start editing at the structural level. Re-read your entire draft and examine the big picture: Does the overall argument flow logically from chapter to chapter? Is your research question clearly answered? Check if your introduction and conclusion are aligned – the conclusion should explicitly address the goals set out in the introduction. Ensure there is no contradiction or unexplained gap in your reasoning.

At this stage, you might decide to reorganise paragraphs or sections for better coherence. It can be helpful to outline your dissertation after writing to see its skeleton and test whether the structure makes sense (sometimes during writing we digress or repeat points – editing is the time to fix that).

Refining writing at paragraph and sentence level

Next, refine the writing at paragraph and sentence level. Read each paragraph critically: does it have a clear topic sentence? Does every sentence logically relate to the main idea of that paragraph? Remove redundancy – you can often tighten a paragraph by deleting repetitive statements or unnecessary words. Make sure each sentence is clear on first read; if you find yourself stumbling over a long sentence, consider splitting it into two.

Check terminology for consistency (for example, don’t switch between “claimant” and “plaintiff”, or “ECJ” and “CJEU”, arbitrarily – pick one term and use it consistently, unless context demands otherwise). Also verify that you have explained any abbreviations or acronyms that you use.

Checking citations and references

Pay attention to your citations and quotations during the proofreading stage. Ensure every citation is complete and formatted correctly. It’s easy to make small errors like an incorrect page number or a missing italicisation of a case name – now is the time to catch and correct those.

Cross-check the citations in your footnotes or in-text references against your bibliography: every source cited should appear in the reference list, and vice versa. If you quoted any source, double-check that the quote is exact and appears within quotation marks with an appropriate reference. Likewise, make sure any paraphrased ideas are properly attributed.

Final proofreading and submission checks

Proofreading for language mechanics is also crucial. Run a spell-check, but do not rely on it solely – it won’t catch legal proper nouns or words that are spelled correctly but misused. Manually proofread to catch typos, punctuation errors and formatting inconsistencies.

It often helps to proofread a printed copy or to read your work out loud; this can make awkward phrasings or errors more noticeable. Some students have a friend or family member read through the dissertation to spot unclear bits or mistakes – just ensure the person is only suggesting changes and not rewriting anything (to maintain academic integrity). Many universities also have writing centres or support services that can provide a proofreading checklist or even review a sample of your work for common issues.

During the final edit, also check all the “technical” details. Are your page numbers, headings and font size/margins in accordance with the submission guidelines? Did you include all required components (for example, a signed declaration, abstract, cover sheet)?

These might seem minor, but failure to adhere to formatting rules can annoy examiners or even cost you marks under presentation criteria. It’s worth making a final checklist to tick off all administrative and formatting requirements.

Finally, ensure you remain within the word limit. Most dissertations have a word count policy (for instance, 10,000 words ± 10%). Know what is included or excluded from the word count – usually footnotes are included or excluded based on specific rules, and appendices typically don’t count.

If you are over the limit, you will need to cut down in the editing phase by being more concise. If you are under, consider whether you have analysed things in sufficient depth. It’s not advisable to add fluff just to meet a number, but a dissertation significantly under the word count might be missing some analysis.

Editing can be a lengthy process, often requiring multiple passes. Allocate sufficient time for it in your schedule – some say you should spend as much time editing as you did writing the first draft. While that may not always be feasible, it underscores that polishing your dissertation is a major task, not an afterthought.

A well-edited dissertation reads elegantly and confidently. It allows your hard-won research and insights to stand out, unmarred by sloppy writing or presentation.

Conclusion

Writing a law dissertation is undoubtedly a demanding undertaking, but it is also one of the most intellectually enriching experiences in legal education. In completing a dissertation, you prove your capacity to conduct independent legal research – framing a pertinent question, critically analysing sources and formulating your own reasoned argument.

This process transforms you from a consumer of knowledge (studying textbooks and lecture notes) into a producer of knowledge. It is an achievement to take pride in.

By following a structured approach – from choosing the right topic, through rigorous research and careful writing, to thorough editing – you can navigate the challenges step by step. Along the way, you will deepen your expertise in your chosen area of law, whether it be constitutional law, international trade, criminal justice or any other field.

You will also hone transferable skills: research skills, analytical thinking, project management and written communication. These skills are highly valued in legal practice and other professional arenas. In fact, graduates who have completed dissertations often possess a level of specialist knowledge and research ability that sets them apart in interviews and jobs (Kherbane 2015).

In conclusion, approach your law dissertation as both an academic journey and a personal challenge. There will be moments of frustration – every researcher encounters dead ends or writer’s block at some point – but perseverance and good planning will carry you through.

Use the support available (your supervisor and academic resources), but also trust in your own abilities to steer the project. If you stay organised, remain critical and curious, and write with clarity, you will produce a piece of work that meets the standards of your degree and perhaps even contributes to a better understanding of the legal issues at stake.

Writing a law dissertation is not easy. However, the reward is not just a grade or a degree requirement checked off. There is also the deep satisfaction of having taken a complex legal question and, through your own effort, turned it into a coherent, insightful piece of scholarly writing. That sense of accomplishment, and the knowledge you gain in the process, will be with you long after graduation.

For expert guidance on writing law dissertations, our UK-qualified writers offer tailored academic support. Explore our law dissertation help page to find out more.

References:

- Kherbane, R. (2015) “Why law students should consider writing a dissertation”. The Guardian, 3 July 2015.

- Moffatt, P. (2020) “Three problems students face when writing a dissertation – and tips to address them”. LawCareers.Net, 27 Oct 2020.

- LawTeacher (2018) “Writing a Law Dissertation – what is expected?” LawTeacher.net, 7 Mar 2018.

- Queen Mary University of London (2024) Student Handbook 2024/25: Dissertation Writing Guidelines. School of Law, QMUL.

- Taylor, B. (2021) “The Legal Practice Course (LPC) – A Guide”. FindAMasters.com, 09 Aug 2021.

- The Lawyer Portal (2025) “What is the LPC LLM?” TheLawyerPortal.com.

- UK Essays. (2018). How to write a master’s dissertation proposal. UKEssays.com, 03 Apr 2018.

- Lammasniemi, L. (2021) Law Dissertations: A Step-by-Step Guide. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- UKDiss (2025) “Introduction to a dissertation”. UKDiss.com, 29 October 2025.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: