Bridges’ transition model of change

Info: 2492 words (10 pages) Study Guides

Published: 28 Dec 2025

If you’re applying Bridges’ Transition Model in an essay or any other academic task, our UK‑qualified writers can support you in presenting your ideas clearly and effectively. See our business assignment help page to learn more.

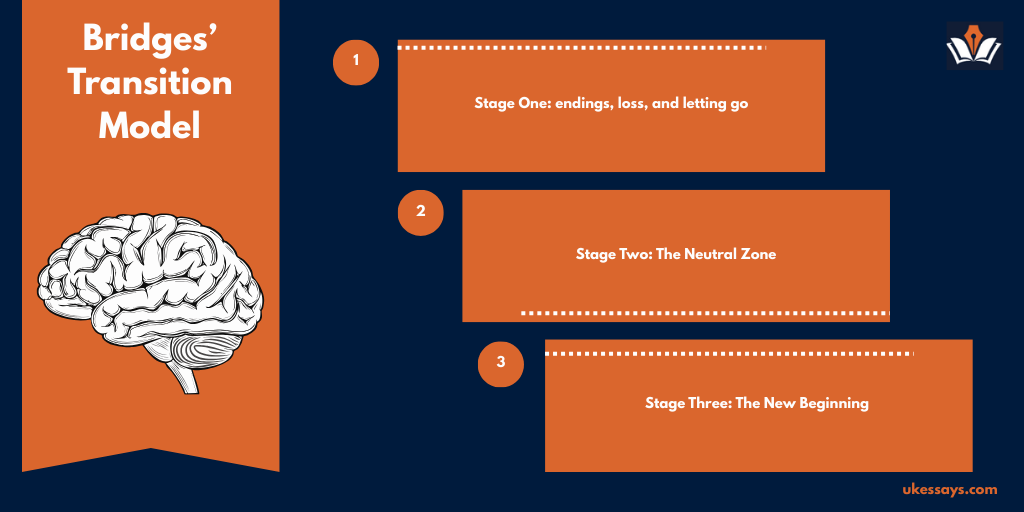

Change is a constant feature of modern organisations. However, individuals often experience it not as a simple event but as an internal psychological journey. William Bridges’ transition model, first introduced in 1991, focuses on this human side of change, emphasising how people gradually move from endings, through uncertainty, to new beginnings (Bridges, 1991).

Bridges’ model highlights the emotional and cognitive transitions that individuals undergo when adapting to new situations (Bridges, 1991; Bridges and Bridges, 2017). Developed over three decades ago, it has been widely applied in guiding organisational change efforts because it recognises that change will only succeed if leaders also address the personal transitions that accompany it.

Indeed, a well-planned change initiative can falter unless managers help people at each step of the transition. They must enable employees to let go of the old ways and navigate the ambiguous “in-between” period. Only then can people eventually embrace the new reality (Bridges, 1991). This approach has resonated with many practitioners and researchers. Evidence shows that supporting employees emotionally during change improves outcomes such as engagement and retention (Leybourne, 2016).

Change versus transition

Bridges draws an important distinction between change and transition. Change refers to the external event or situation. For example, it could be a new company policy, a restructuring, or the introduction of a different technology. Such changes can happen quickly and may be mandated from the top.

Transition, by contrast, is the inner psychological process that people go through to come to terms with a new situation. It is inherently personal and usually unfolds more slowly than the external change event. In practice, even after a change has officially “happened”, employees may still be in the midst of transition. For example, an organisation might announce a merger or roll out a new software system. However, its staff will continue to grapple with uncertainty, emotional reactions, and the redefinition of their roles.

Bridges’ core insight is that change management must address these internal adjustments. Empathetic leaders recognise that significant change often puts people in a state of flux or even crisis. Therefore, people need support to navigate the psychological journey (Bridges, 1991; Bridges and Bridges, 2017).

The starting point for managing transition is not simply implementing the new solution, but rather helping people deal with what is ending. Often this means letting go of familiar routines or identities that had been part of the old way of working. Only by acknowledging and managing these endings can people open up to accepting the new beginning (Bridges, 1991).

Stage 1: ending, losing and letting go

According to Bridges, every transition begins with an ending. This first stage involves people letting go of what used to be. When a change is introduced, individuals initially focus on what they are losing. This might include comfortable routines, established relationships, or even a sense of competence in an old role. Not surprisingly, this stage often triggers resistance and emotional upheaval (Bridges, 1991).

Common reactions include fear, anger, denial, sadness, disorientation and a sense of loss. For example, a long-standing process might be replaced by a new system. Employees who mastered the old way could feel anxious about losing their expertise. They might even become resentful of having to abandon skills they had perfected. At this point, people have not yet bought into the new situation. They are still grappling with the reality that something is ending.

It is crucial for leaders to accept and acknowledge these emotions. They should also allow people time to mourn the loss of the old (Bridges, 1991; Bridges and Bridges, 2017). If management ignores or minimises people’s feelings at this stage, resistance is likely to increase. Employees might cling to the past or actively oppose the change.

To guide people through Stage 1, leaders should communicate openly about why the change is necessary. They must listen empathetically to concerns and provide reassurance about what will remain intact (Bridges and Bridges, 2017). They can also help individuals see that their existing skills and experience will still be valued. This assurance shows employees that their strengths have a place in the new context.

By validating the sense of loss and showing support, change leaders lay the groundwork for trust. This in turn makes it more likely that people will begin to loosen their grip on the old ways. They can then start to prepare to move forward (Bridges, 1991).

Stage 2: the neutral zone

After the initial ending, people enter what Bridges calls the neutral zone. This is an ambiguous intermediate phase where the old reality has been left behind. In this stage the new reality is not yet fully in place (Bridges, 1991). In organisational transitions, this is often the most challenging stage.

The neutral zone can feel disorienting and stressful. People may be uncertain about their new roles and overwhelmed by new processes that are still in flux. It is common to see lower morale and productivity during this period. Many people also experience increased anxiety and scepticism (Bridges, 1991; Bridges and Bridges, 2017). For instance, employees might question whether the change will really work. They may also worry about how their responsibilities and identity in the organisation are evolving.

However, Bridges argues that the neutral zone is not purely negative. It is also a critical time of renewal and innovation if managed well. Because old assumptions have been loosened, this in-between phase can spark creativity and open-minded problem solving. People are exploring new approaches even as they feel vulnerable (Bridges, 1991).

To support people in the neutral zone, leaders should provide structure and short-term goals to create some stability amidst uncertainty. Regular check-ins, feedback, and open dialogues are important so that employees do not feel adrift. Managers might set quick wins – small attainable targets – to build confidence and demonstrate progress (Bridges and Bridges, 2017).

It is also vital to remind everyone of the bigger purpose and vision behind the change. This reinforces the rationale that motivated the transition in the first place. By guiding people with clarity and compassion through the neutral zone, leaders help prevent drift or burnout. They also encourage employees to experiment and contribute to shaping the new ways of working. Over time, confidence slowly builds and confusion starts to subside. As this happens, the group becomes more ready to move into the final phase of transition.

Stage 3: the new beginning

The final stage of Bridges’ model is the new beginning. Here, people start to embrace the change and see themselves moving forward into a fresh reality. In the new beginning stage, there is a noticeable rise in energy, openness and commitment (Bridges, 1991). Individuals have accepted the need for change and are adopting new behaviours and attitudes. They have a clearer understanding of their roles in the changed environment. They can also see early wins or benefits resulting from their efforts.

For example, after implementing a new project management system, a team may not see benefits immediately. However, after a period of adjustment they could start to experience increased efficiency or better collaboration. These improvements reinforce their acceptance of the new tool. In this phase, motivation rebounds as people feel a renewed sense of purpose and identity aligned with the change.

Bridges emphasises that while this stage is positive, it must be nurtured carefully (Bridges and Bridges, 2017). Leaders should celebrate the milestones achieved and recognise individuals’ contributions in reaching the new beginning. This helps to cement the change as the “new normal” and encourages lasting adoption.

At the same time, managers need to remain vigilant. Not everyone will arrive at the new beginning at the same time. Some individuals might even slip back into old mindsets temporarily if they encounter setbacks (Bridges, 1991). Therefore, reinforcing the new behaviours through continued support, training and feedback is key to sustaining the transition.

When well managed, this stage leaves people feeling reoriented and renewed. They also have greater confidence in the future (Bridges and Bridges, 2017). At both an individual and organisational level, a successful new beginning means the change has truly taken root. In other words, the workforce has psychologically shifted to embrace the new state of affairs.

Managing the transition process

Bridges’ model not only describes the stages of transition but also offers guidance for facilitating transitions effectively. Managing the human side of change requires deliberate actions that complement any formal project plan. Key practices recommended by Bridges and colleagues include the following (Bridges and Bridges, 2017):

- Communicate the purpose – Clearly articulate why the change is needed and what goals it seeks to achieve. People are more willing to let go of the old ways when they understand the rationale. They also need to see the bigger picture.

- Acknowledge and engage – Allow those affected by the change to express their feelings and concerns. Gather feedback to understand the impact on them, and involve them in the transition process. This engagement helps build buy-in and trust.

- Assess readiness – Evaluate the organisation’s “transition readiness”. For example, determine whether there are sufficient resources and leadership support to help people through the change. Address any gaps (e.g. by providing training or coaching) to improve readiness.

- Support and educate leaders – Ensure that managers themselves understand how change can emotionally affect people. Equip leaders at all levels with the skills to guide their teams through uncertainty. When leaders are empathetic and competent in managing transition, employees feel safer and more supported.

- Set short-term wins and milestones – As noted earlier, quick wins are vital in the neutral zone. Plan for some early successes that teams can achieve and celebrate. These milestones provide evidence that the transition is on track. This in turn boosts morale and motivation.

- Reinforce new beginnings – Once people start embracing the change, reinforce it. Recognise and reward behaviours that align with the new way of working. Continually communicate success stories and the benefits emerging from the change. This consolidation phase ensures that the change is sustained. It also prevents people from reverting to old habits.

By following these steps, organisations can create a more emotionally sustainable change process (Leybourne, 2016). In practice, this might involve change managers acting as transition coaches. They help individuals navigate the personal journey alongside implementing the technical aspects of the change.

Numerous case studies have demonstrated that attending to the transition (not just the change itself) leads to better outcomes. For example, organisations report faster adoption of new initiatives and lower employee turnover when they focus on the human side of change (Leybourne, 2016).

Real-world example: Atlassian’s transition to remote work

A useful example of Bridges’ model in action can be seen at the Australian tech company Atlassian, which underwent a major work policy change in 2020–2021. Atlassian introduced a permanent “Team Anywhere” policy that allows employees to work from anywhere. It requires office attendance only a few times per year (Marsh, 2021). This was a significant shift from traditional office-based work. Employees had to transition psychologically to the new arrangement.

Initially, in the ending stage, many workers had to let go of familiar routines such as daily commutes and face-to-face teamwork. They also had to relinquish the clear separation between home and office life. It is likely that some felt uneasy about losing the structure and social interactions of office work. Atlassian’s leaders acknowledged these concerns and emphasised the benefits of the new policy. They highlighted advantages such as better work–life balance and greater flexibility (Marsh, 2021).

As employees moved into the neutral zone, they had to navigate practical uncertainties. For example, they needed to learn how to collaborate effectively via digital tools and adjust to new norms of communication. The company supported staff through this period by providing resources for remote work. It also offered regular feedback on how to improve virtual teamwork (Atlassian, 2022).

Despite the ambiguities of this phase, it also spurred innovation. Teams experimented with new ways to maintain culture and cohesion while working in a distributed manner. Over time, Atlassian’s workforce began to experience a new beginning as they grew confident in the remote model. Productivity remained strong or even improved. Employees also reported benefits like reclaimed commuting time and the ability to live where they preferred.

Within 18 months of the change, Atlassian saw a surge in employee satisfaction and a record number of new hires. This indicated that the organisation had successfully embraced the new way of working (Atlassian, 2022).

In sum, Atlassian effectively managed the transition that accompanied its strategic shift to remote work. It did so by consciously guiding employees through each phase – helping them address fears and losses in the ending, supporting them during the neutral adjustment period, and leading them into a positive new beginning.

Wrapping up:

Bridges’ transition model provides a profound reminder that change is not just an operational issue but a human one. By concentrating on the psychological transition rather than only the external change event, the model helps leaders foster resilience and adaptability in their teams.

Each stage – ending, neutral zone, and new beginning – comes with its own challenges and opportunities. Understanding these phases enables managers to tailor their support. For example, they can move from empathetically handling losses, through steering people during an uncertain limbo, to ultimately celebrating and solidifying new starts.

The model is arguably more relevant than ever in today’s fast-paced environment. Organisations frequently face transformations that require not just new processes but genuine buy-in from their people.

However, Bridges’ framework is not a standalone recipe for success. It works best in conjunction with sound project management and a clear strategic direction (Bridges and Bridges, 2017). What it offers is a compassionate, psychologically informed approach that can dramatically improve how change is experienced.

Indeed, research and practice over the past decades have reinforced Bridges’ core insight. When people are guided through the emotional landscape of transition, they are far more likely to embrace change and carry its benefits forward (Leybourne, 2016). In an era of constant change, that lesson is one that leaders ignore at their peril.

If you’re applying Bridges’ Transition Model in an essay or any other academic task, our UK‑qualified writers can support you in presenting your ideas clearly and effectively. See our business assignment help page to learn more.

References:

- Bridges, W. (1991) Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Bridges, W. and Bridges, S. (2017) Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change (4th edn). London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Leybourne, S.A. (2016) ‘Emotionally sustainable change: two frameworks to assist with transition’, International Journal of Strategic Change Management, 7(1), pp. 23–42.

- Marsh, S. (2021) ‘Atlassian’s work from home policy to see staff come into the office just four times a year’, 9News, 29 April. Available at: https://www.9news.com.au/national/atlassian-work-from-home-policy-into-the-office-four-times-a-year/8b9d8a3d-d61e-48e1-9e41-366abd027100 (Accessed 10 December 2025).

- Atlassian (2022) ‘Atlassians are on the move as our people embrace Team Anywhere’, Atlassian Blog (Inside Atlassian), 6 April. Available at: https://www.atlassian.com/blog/inside-atlassian/embracing-team-anywhere (Accessed 10 December 2025).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: