Balanced scorecard guide

Info: 2661 words (11 pages) Study Guides

Published: 06 Oct 2025

Need clarity on the balanced scorecard? Get tailored management assignment help from a UK-qualified expert and boost your grades today.

The balanced scorecard (BSC) is a strategic planning and performance management framework. It gives organisations a balanced view of performance beyond traditional financial measures (Kaplan and Norton, 1992).

Kaplan and Norton introduced the BSC in the early 1990s to address the limitations of relying solely on financial metrics. Traditional financial measures often gave misleading signals for continuous improvement and innovation. As a result, managers gain a holistic perspective of business health. They can better link short-term actions to long-term competitive success.

The balanced scorecard has since evolved into a comprehensive strategic management system. Organisations across industries and sectors worldwide have embraced the BSC as a tool to improve performance (Balanced Scorecard Institute, n.d.).

Indeed, more than half of major companies globally have adopted the BSC as a strategy management tool (Balanced Scorecard Institute, n.d.). Public sector agencies and non-profit organisations have also implemented adapted versions of the BSC to improve mission outcomes.

Moreover, management surveys consistently rank the balanced scorecard among the top strategic management tools globally (Rigby and Bilodeau, 2018). Harvard Business Review’s editors cited the BSC as one of the most influential business ideas of the past 75 years (Sibbet, 1997). This recognition underscores the scorecard’s lasting impact on management practice.

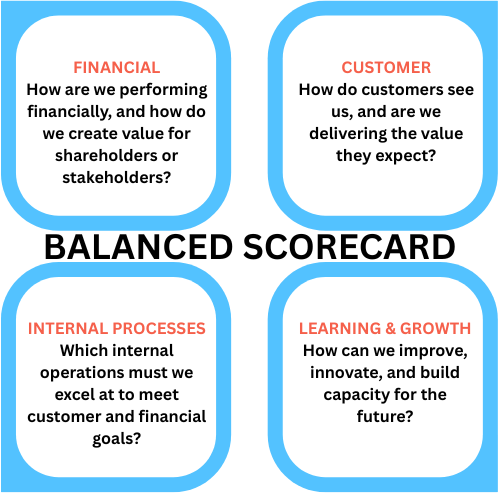

The four perspectives of the balanced scorecard

At its heart, the balanced scorecard is built around four interrelated perspectives. Together, these provide a balanced view of organisational performance (Kaplan and Norton, 1992). Each perspective focuses on a different set of objectives and metrics. This approach ensures that managers do not concentrate on one dimension at the expense of others.

These four perspectives translate the organisation’s vision and strategy into specific, measurable targets (Kaplan and Norton, 1996). By examining goals and indicators across multiple areas, companies maintain a mix of short-term and long-term priorities.

Financial perspective

The financial perspective addresses a fundamental question: How is the organisation performing financially? It also considers how the organisation creates value for its shareholders (or for the budget in public organisations).

This perspective includes traditional financial metrics such as revenue growth, profitability, return on investment and cost management.

- In a for-profit business, financial objectives might include increasing annual sales by a certain percentage or improving profit margins.

- For a government agency or charity, this perspective instead emphasises efficient use of funds and cost-effectiveness (Balanced Scorecard Institute, n.d.).

The financial perspective remains crucial, because strong financial results ultimately sustain the strategy and provide resources for future growth.

Customer perspective

The customer perspective considers how customers perceive the organisation. It asks: How do our customers see us, and are we delivering value to them? This perspective typically measures customer satisfaction, retention, loyalty, market share and service quality. For example, a company might track its net promoter score or on-time delivery rate as key performance indicators. It could also monitor how quickly customer complaints are resolved as a measure of service quality.

High performance in customer metrics indicates that the organisation is meeting customer needs, which usually precedes strong financial results. Therefore, the balanced scorecard links customer objectives with financial goals — satisfied customers drive revenue growth and profitability (Kaplan and Norton, 1996).

Internal processes perspective

The internal processes perspective looks at the efficiency and quality of the organisation’s internal operations that create value. It identifies the business processes most critical for achieving the customer and financial objectives. It then tracks how well those processes are performing using appropriate metrics.

This ensures the organisation excels at the internal activities needed to satisfy customers and achieve financial targets. By doing so, organisations can deliver better outcomes more efficiently through continuous improvement of key processes (such as production, logistics or customer support workflows).

Learning and growth perspective

The learning and growth perspective focuses on the intangible drivers of future success. (It is sometimes called the organisational capacity or innovation perspective.) This view covers the people, information and cultural factors that enable improvement and long-term growth.

It addresses questions like: How can we continue to improve and create value? This perspective measures employee skills and training, knowledge management, culture and morale, and technological infrastructure.

Strong performance in learning and growth metrics indicates that the organisation is building capacity for the future. These improvements will enable it to excel in the other three perspectives.

In essence, this perspective ensures the company is investing in its future. It develops talent, builds necessary tools, and fosters a culture of continuous improvement to drive strategic success (Kaplan and Norton, 1996).

Developing and implementing a balanced scorecard

Building an effective BSC requires translating the organisation’s high-level strategy into specific objectives, measures and targets. These should cover all four scorecard perspectives.

In practice, developing a BSC starts by clarifying the organisation’s vision and strategic goals. Next, the team identifies a handful of strategic objectives within each perspective that are most critical for success (Niven, 2006).

For each objective, managers define how to measure progress – typically by selecting key performance indicators (KPIs). They also set specific targets for these measures to quantify the desired results.

The BSC connects strategy to actions, so it is important to select measures that are meaningful and logically linked. Improvements in learning and growth should drive better internal processes. In turn, stronger processes should lead to enhanced customer outcomes and, ultimately, improved financial performance.

The strategy map is another important implementation tool. It provides a visual representation of the cause-and-effect relationships among objectives in the different perspectives (Kaplan and Norton, 2004).

Managers typically create a one-page strategy map to illustrate these connections. For example, it might show that improving employee training (a learning perspective objective) will boost service quality (an internal process outcome). This, in turn, leads to higher customer satisfaction (customer perspective) and ultimately increases revenue (financial perspective).

Example strategy maps:

- Mobil – https://hbr.org/2000/09/having-trouble-with-your-strategy-then-map-it

- Amanco (Page 8 of the PDF) and Riau (page 13 of the PDF) – https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%2520Files/WP21-028_Triple_Bottom_Line_8.28.20abstract_correction_dd38a54c-48f2-4471-80db-e0ed6f962309.pdf

In the following video you can see how a balanced scorecard strategy map is created using the ‘Strategy Scorecard Wizard’ tool:

Once created, leaders should communicate the strategy map throughout the organisation. This helps employees at all levels understand how their work contributes to strategic goals. Such understanding increases buy-in and alignment.

Once the top-level scorecard is set, the approach encourages cascading the scorecard throughout the organisation (Balanced Scorecard Institute, n.d.). Cascading means developing aligned scorecards for departments, teams and business units. Each level defines its own relevant objectives and KPIs that support the overarching strategy. As a result, the entire organisation stays focused on a common strategic agenda. Individuals can see a clear line of sight from their day-to-day activities to the higher-level goals (Kaplan and Norton, 2000).

Regular monitoring and review are essential. Many organisations hold monthly or quarterly strategy meetings to discuss BSC results, assess progress on targets, and decide on corrective actions if performance is lagging. By integrating the balanced scorecard into routine management processes, organisations ensure that strategy execution becomes a continual, focused effort. It is not a one-time exercise.

The nine steps to success

While Kaplan and Norton provided the conceptual foundation for the balanced scorecard, many organisations found implementation challenging. To address this, the Balanced Scorecard Institute developed the Nine Steps to Success™ framework, a structured methodology for designing, deploying and sustaining a scorecard system. It complements, rather than replaces, the original model by offering a practical, repeatable process for turning strategy into action (Balanced Scorecard Institute, n.d.).

The nine steps begin with organisational assessment and end with performance sustainability. They are:

- Assessment – evaluating readiness, leadership commitment and organisational context.

- Strategy – refining mission, vision and core values to clarify strategic intent.

- Objectives – identifying strategic objectives within the four perspectives.

- Strategy mapping – creating a visual cause-and-effect map linking objectives.

- Performance measures – selecting key indicators to monitor progress.

- Initiatives – defining actions and projects that drive performance improvement.

- Automation – integrating scorecard data into management systems for monitoring.

- Cascade – aligning departmental and individual scorecards with the enterprise-level system.

- Evaluation – reviewing, adapting and sustaining the strategy management process.

Each step reinforces the link between strategic intent and operational execution. In essence, the Kaplan–Norton framework provides what to measure, while the Nine Steps model provides how to implement it. This combination enhances strategic alignment, ensures disciplined follow-through, and builds an enduring performance management culture. Many organisations adopt this approach to embed the balanced scorecard effectively, ensuring it becomes a living management system rather than a static reporting tool.

Adapting the balanced scorecard to different sectors

Organisations in manufacturing, healthcare, education, government and non-profit sectors have all applied the balanced scorecard successfully (Madsen, 2025). Core principles remain the same — the BSC maintains a balance between financial and non-financial goals. However, each perspective’s emphasis is tailored to fit the organisation’s mission.

For instance, in public sector and charitable organisations, financial metrics (like staying within budget) serve as important constraints. However, the ultimate measures of success are mission-related outcomes or stakeholder satisfaction rather than profit. These organisations often relabel the financial perspective as a “Stewardship” perspective to highlight responsible use of funds. They also place the customer (or citizen) perspective at the top of their scorecard (Niven, 2008).

A government agency might measure success through community impact or service quality delivered to citizens. Financial efficiency is viewed only as a supporting goal.

In contrast, a private sector company typically prioritises financial results for shareholders. However, it will still use customer, internal, and learning perspectives to drive those results.

Adapting internal process metrics:

Different industries adapt internal process metrics to what matters in their domain. For example:

- A hospital’s internal measures may focus on patient care pathways and safety indicators.

- By contrast, a software company might track product development cycle time or system uptime.

The balanced scorecard’s flexibility allows it to be customised. Organisations choose objectives and metrics that make sense for their strategic context. Ultimately, the BSC provides a disciplined approach to translate strategy into operational terms in any context – be it a bank, a university or a government department. It ensures that everyone is working toward common objectives.

Benefits of using the balanced scorecard

When implemented well, the balanced scorecard offers several benefits for strategic management and performance improvement.

Firstly, it provides a clear framework that translates vague strategic visions into a coherent set of goals and measures. This structured approach ensures that all key areas are considered – financial, customer, internal, and learning. This breadth prevents tunnel vision on short-term financial metrics alone (Kaplan and Norton, 1996).

Secondly, the BSC improves communication of strategy throughout the organisation. Leaders can use strategy maps and concise measures to convey priorities and expectations more effectively. This approach aligns teams and departments with the overall game plan. Employees can see how their individual objectives link to broader organisational goals. This clarity in turn fosters engagement and a greater sense of purpose.

Another key benefit is alignment: the balanced scorecard ensures organisational activities and initiatives support the strategy. It forces management to focus on a few strategic objectives in each perspective, rather than juggling hundreds of uncoordinated KPIs. This prioritisation and alignment help break down silos, as different parts of the business work toward shared outcomes (Jackson, 2020).

The BSC also encourages regular strategic review. Organisations that adopt it tend to establish a cadence of monitoring and discussing performance on strategic objectives, rather than simply reviewing financials. As a result, strategy becomes a continual process and can adapt more quickly when conditions change.

Finally, the BSC balances short-term financial targets with metrics on customer loyalty, internal efficiency and innovation — factors that drive future success. This balance helps organisations avoid the pitfall of short-termism and fosters sustainable performance improvement (Madsen, 2025).

Challenges and limitations

The balanced scorecard is a powerful tool, but there are challenges and pitfalls that organisations must navigate.

One common issue is that developing a good BSC can be complex and time-consuming. Building a useful scorecard requires careful thinking to choose the right objectives and metrics. If too many indicators are tracked, the scorecard can become unwieldy. On the other hand, if important areas are omitted, it loses value. Organisations sometimes struggle to select meaningful non-financial measures. They may even copy metrics from generic examples that do not reflect their unique strategy (Norreklit, 2000).

Critics note that assumed cause-and-effect relationships in a BSC do not always hold in practice (Norreklit, 2003). For example, improving employee training will not automatically boost customer satisfaction without the right conditions in place. Some argue that many scorecards lack empirical validation for their claimed links.

Successful implementation also hinges on strong leadership commitment and cultural buy-in (Antonsen, 2014). Without top management support, a balanced scorecard initiative may falter. It could be seen as just an additional reporting burden rather than a new way of managing. Ensuring that all levels of the organisation understand and embrace the BSC concept is crucial.

Another challenge is integrating the BSC into existing systems and processes. Some organisations fail by treating the scorecard as a one-off project. They might create a nice-looking scorecard but not change how meetings, reviews, and rewards are structured. Consequently, the BSC might sit on a shelf instead of driving real change. It is vital to embed the scorecard into routine management processes. For example, leaders should use BSC results in management meetings and decision-making, and link incentives to BSC measures. This way the scorecard becomes a living tool.

There are also practical difficulties in data collection and reporting. Gathering timely and accurate data for various non-financial metrics can be challenging and resource-intensive. If data systems are inadequate or teams rely on cumbersome spreadsheets, maintaining the scorecard can become a frustrating exercise. To address this, many organisations use specialised performance management software to automate data capture and reporting for their scorecards.

Finally, the balanced scorecard needs to be flexible and updated as strategies evolve. If the business environment shifts or goals change, the scorecard should be revised. A static scorecard can quickly become obsolete. In summary, organisations must be prepared to invest effort into designing, implementing, and continuously refining the balanced scorecard. If these challenges are addressed, the BSC can deliver on its promise. But if they are ignored, even a well-designed scorecard may not give the desired results.

Need clarity on the balanced scorecard? Get tailored management assignment help from a UK-qualified expert and boost your grades today.

References and further reading:

- Antonsen, Y. (2014) ‘The downside of the Balanced Scorecard: a case study from Norway’, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(1), pp. 40–50.

- Balanced Scorecard Institute (n.d.) ‘Balanced Scorecard Basics’. Balanced Scorecard Institute website. Available at: balancedscorecard.org (Accessed 30 September 2025).

- Jackson, T. (2020) ‘A thorough list of Balanced Scorecard advantages & disadvantages’, ClearPoint Strategy Blog. Available at: https://www.clearpointstrategy.com/blog/thorough-list-of-balanced-scorecard-advantages-disadvantages (Accessed 30 September 2025).

- Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1992) ‘The balanced scorecard—measures that drive performance’, Harvard Business Review, 70(1), pp. 71–79.

- Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1996) The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (2000) The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (2004) Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Madsen, D.Ø. (2025) ‘Balanced Scorecard: History, Implementation, and Impact’, Encyclopedia, 5(1), 39. doi:10.3390/encyclopedia5010039

- Niven, P.R. (2006) Balanced Scorecard Step-by-Step: Maximizing Performance and Maintaining Results. 2nd edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Norreklit, H. (2000) ‘The balance on the Balanced Scorecard – a critical analysis of some of its assumptions’, Management Accounting Research, 11(1), pp. 65–88.

- Norreklit, H. (2003) ‘The Balanced Scorecard: what is the score? A rhetorical analysis of the Balanced Scorecard’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(6), pp. 591–619.

- Rigby, D. and Bilodeau, B. (2018) Management Tools & Trends 2018. Boston: Bain & Company.

- Sibbet, D. (1997) ‘75 years of management ideas and practice 1922–1997’, Harvard Business Review, 75(5), pp. 2–12.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: