Advising and Students’ Academic Success

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Teaching |

| ✅ Wordcount: 4194 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Student retention and persistence to graduation are ongoing problems and have been for some time now especially in engineering technology (ET) programs around the country. It is a well-established fact that the quality of interaction between a student and a concerned individual on campus, often through academic advising, is a key contributor to college retention. Over the years professional academic advisors has developed effective advising strategies that research show have positively impacted students’ retention and their persistence to graduation. In this study, a national survey was conducted among academic advisors of ET programs in the USA. Results show that personalized and caring advising, being proactive and keeping students focused on their plan of study, actively listening students’ complaints and concerns and acting on them, and believing in them helped ET students’ retention and persistence to graduation. On the other hand, being passive, ignoring students’ complaints and concerns, embarrassing them on their academic struggles and limited knowledge about the curriculum and departmental procedures and practices are found to be the least effective. The overall contribution of this study to ET body of knowledge is that it provides ET academic advisors a set of best practices for student success. The findings of the study will also benefit ET faculty members, who directly or indirectly advise students, by sharpening their advising practices.

Introduction

Academic advisors are committed to the students they advise, their institutions, their professional practices, and the broader advising and educational community they serve. Academic advising is one of the best ways to assist the personal, intellectual, and social development of students. Advising as a service to students connects students’ academic and personal worlds; therefore, advising cultivates their holistic development. Well advised students are (a) more likely to enroll, (b) less likely to take classes that do not contribute towards graduation, (c) more likely to enjoy college, (d) more likely to balance study, work and personal life, (e) more apt to persist to graduation. The process of academic advising is important to institutions of higher education and the role of the academic advisor is critical to student retention and student satisfaction with the institution (Gerdes and Mallinckrodt 1994; Corts, et al. 2000; Thompson, et al. 2007; Hester 2008).

Academic Advisors in Engineering Technology (ET) programs play a major role by providing students timely and accurate information to cultivate connections, success, and advancement in engineering excellence. Besides academic planning, advisors help students with career goals, choice of major, field of specialization, degree requirements, general education requirements, academic policies and procedures, student petitions, and even provide support when students are in academic difficulty (Hagen 2008).

National data shows that approximately 60% of students leave engineering during their first-year (Marcus 2012). Several studies have identified various reasons why students leave engineering and/or engineering technology programs and do not earn degrees. One of the important factors identified in these studies was poor advising/guidance that students receive during their time of study (Cairncross, et al. 2015; Meyer 2014; Marra, et al. 2012). On the other hand, a sense of connection with academic advisor helps students feel like they belong at the institution and the program. When students feel connected to the campus community, they are more often retained and excel academically, creating a winning situation for everyone.

This paper examines effective strategies used by professional academic advisors in ET programs. A questionnaire is developed and completed by advisors to understand best practices that results in better students’ retention and persistence to graduation. It was anticipated that the results of the investigation would lead to a set of empirically-based recommendations to create a more effective academic advising system at colleges and universities that offer ET programs.

Advising and Students’ Academic Success

Academic advising when purposefully planned plays an important role in supporting students’ academic success. Effective retention programs reflect university administrators’ understanding that academic advising underpins student success (Tinto 1993,1999). (Kuh, et al. 2005) further affirm the role of academic advising in supporting students. They suggested that “advising is viewed as a way to connect students to the campus and help them feel that someone is looking out for them” (p. 214). This connection reflects an institutional commitment to the student and his or her education, which Tinto also finds essential to effective retention programs. Academic advisors try to keep students interested and engaged by building a successful rapport with them. This allows students to feel comfortable in an academic setting and they tend to be motivated to follow through and progress to graduation with degrees in engineering

Study Method

In order to identify advising best practices for ET programs, a systematic method was followed, which is described below

Step 1: For this project a questionnaire survey was created. Questions for the survey were created through extensive literature review and direct collaboration with the academics advisors in the authors’ department. National Academic Advising Association’s resource webpage and its journal provided a plethora of information about advising excellence which helped shaping the survey structure (NACADA 2018).

Step 2: Since human subjects were involved an Institutional Research Board (IRB) proposal was submitted and was approved to conduct the survey.

Step 3: A national ET academic advisor contact list was created by visiting individual university and department’s website. Only advisors who advises ET students were included on the list.

Step 4: For the survey instrument REDCAP was used, which is a secured surveying tool available at the authors’ university.

Step 5: An invitation to complete the survey was sent to ET academic advisor contact list. The survey was kept open for three months and several reminders were sent to remind ET advisors to complete the survey.

Data Collection and Analysis

A total of 22 complete surveys were received with a response rate of about 11%.

Basic Demographic Information of the Advisors

The survey participants were seventeen females and five males with an average of 8 years of experience in advising. They all have college degree and 25% of the advisors have advanced degree (master’s degree). Some of these advisor worked in multiple institutions before their current positions. All of the advisors have received training on advising provided by their respective institutions. Advisors mentioned that they regularly attend conferences organized by NACADA, TASSR, FYEE and various professional development activities.

Advisors’ Responsibilities

ET advisors maintain a busy schedule. Their primary responsibility is to help students with the courses and support them toward graduation. According to the survey, ET advisors advise an average of 280 students. Typically they advise all Engineering Technology majors that consist of traditional (100%), non-traditional (100%), transfer (100%), undecided/undeclared (54%) and others (23%). ET students are required to meet the advisor at least once a semester for course advising and progress. However, students with questions and concerns can meet multiple times during a semester. ET advisors also meet students with probation multiple times during a semester. Besides advising, many ET advisors hold other responsibilities such as teaching courses, recruitment, orientation, graduation paperwork, services in university committees, etc. ET advisors use wide variety of tools for advising purposes. Most commonly used advising tools are MyAdvisor, DegreeWorks, Banner System, Boilerconnect, Peoplesoft, Starfish, TechConnect, Course map. Some of these student success platforms combine predictive analytics with communication and workflow tools to help support, retain and graduate students.

Advising Methods/Models used for Engineering Technology Students

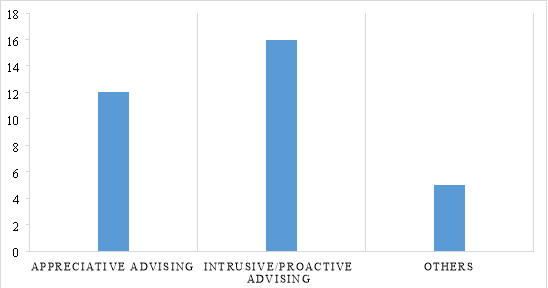

Strong academic advising has been found to be a key contributor to student persistence (Center for Public Education, 2012). A key step in delivering upon a commitment to student success includes purposeful advising practice. Various advising strategies exist, each of which has its own proponents. The survey asked advisors if they use any specific advising model or method when advising Engineering Technology students. Advisors mentioned that they employ mixed methods depending on the student and the situation. Advising methods that they found most effective for Engineering Technology students were appreciative advising, proactive/intrusive advising and learning-centered advising (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Advising methods/models used by advisor for Engineering Technology students

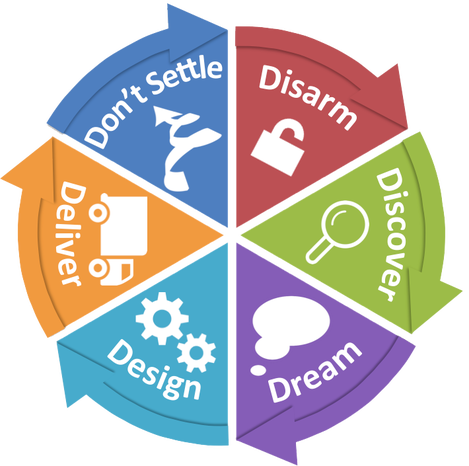

Appreciative Advising is the intentional collaborative practice of asking positive, open-ended questions that help students optimize their educational experiences and achieve their dreams, goals, and potentials (Bloom, Hutson and He 2008). Appreciative advising emerged from an article written by Jennifer L. Bloom and Nancy Archer Martin titled “Incorporating Appreciative Inquiry into Academic Advising” that appeared in the online academic advising journal at Penn State, The Mentor. The Appreciative Advising framework is a six-phase model that advisers can use in their work to help students realize and achieve their greatest hopes and dreams. 1) Disarm: Make a positive first impression with the student, build rapport, and create a safe, welcoming space. 2) Discover: Ask positive open-ended questions that help advisers learn about students’ strengths, skills, and abilities. 3) Dream: Inquire about students’ hopes and dreams for their

Figure 2: Appreciate Advising Model

futures. 4) Design: Co-create a plan for making their dreams a reality. 5) Deliver: The student delivers on the plan created during the Design phase and the adviser is available to encourage and support students. 6) Don’t Settle: Advisers and students need to set their own internal bars of expectations high.

The proactive/intrusive advising model is based on the premise that some students will not take the initiative in resolving their academic concerns, thereby needing the intrusive assistance of assigned advisors. The use of the word “intrusive,” as coined in Walter Earl’s 1987 article, “Intrusive Advising for Freshmen,” is used to describe this model of advising as “action oriented by involving and motivating students to seek help when needed” (Earl 1987). The proactive/intrusive model incorporates the components of prescriptive and developmental advising models, creating a holistic approach that meets a student’s total needs. The model seeks to address problems as they emerge, rather than being reactive. Essentially, advisors reach out to help students instead of waiting for students to seek help. Proactive strategies, such as academic alerts, enable advisors to help students while they still have time and options to improve grades. An example would be a student who is failing multiple courses and seeks help at the end of a semester when it is too late to recover academically. Intrusive modeling theory is based on three premises:

- Academic professionals can be trained to identify freshmen students who need assistance.

- Students do respond to direct contact regarding academic problems when guided help is offered.

- Students can become successful if provided the information about academic and college resources available to them.

Advisors and students benefit from this model in terms of advising effectiveness. For instance, the student-advisor relationship becomes more than just a “registration process” by engaging students in the whole academic process (e.g., career exploration, personal development, study strategies, etc.), thus building connectedness to the institution, and ultimately increasing retention rates.

Learning-centered advising model focuses on students and increases student involvement and facilitates discussion, critical thinking and call to action on the students part where the advisor can step back and do more coaching, mentoring, and counseling. This method places more responsibility on the student to take an active role in their academic planning and allows the advisor use teachable moments and direct students on a path – instead of handing them the all answers immediately without explanation.

Freshmen versus Upper Class Advising Strategies

Among the different groups of students on a university campus, the freshmen students experience most vulnerability as they transition to university life. Many freshmen students display characteristics such as “low academic self-concept, under-prepared, unrealistic grade and career expectations, unfocused career objectives, extrinsic motivation, external locus of control, low self-efficacy, and inadequate study skills for college success a belief that learning is memorizing, and a history of passive learning” (Ender 2000). As a result, sometimes they make poor choices or decisions that impacted negatively on their academics. Advising strategies for such at-risk freshmen students should be different than those for upper class students who already know the system and often know exactly where they are at and what is left for them to finish their education. This has been echoed in the survey as ET advising use distinct strategies for freshmen & at-risk students vs upper class junior and senior students. Establishing a rapport with freshmen and at-risk students is critical to their success. And an academic adviser can play a pivotal role by establishing and maintaining a relationship with these students that is ongoing and purposeful planned and supportive. As this relationship develops, it encourages student making better decisions and independence as they achieve educational, career, and personal goals through the use of the full range of institutional and community resources. One advisor mentioned that “We talk particularly to our freshmen students about resiliency. We try to remind the students that their courses are hard, will be challenging, and to not let this discourage them if they struggle. We try to normalize failure and struggle in college and emphasize resiliency and the importance of continuing to try and seeking out the resources available to succeed. For at risk students, we’re a bit more hands on in our approach. Reaching out more frequently, touching base every few weeks for check ins and seeing how they are progressing. We have excellent resources through an academic support center where we often refer at risk students for more in depth help with study strategies, time management, motivation, and tutoring for math/science courses as well”. For junior and senior students, advising is a combination of academic and career advising. ET advisors spend a lot of time talking about life after graduation, looking at job postings and strategies for finding the job such as strategic use of electives, minors, etc. Advisors also talk about graduate school if the student is interested.

Table 1. Advising Strategies for Freshmen & At-Risk vs Upper Class Students

|

Freshmen and At-Risk Students |

Upper Class students |

|

|

Focus |

student’s development of self-confidence and their ability to make sound decisions |

Combination of academic and career advising |

|

Advising Approach |

Practice/Intrusive, strength-based |

Appreciate |

|

Strategies |

|

|

Effective Advising strategies for ET students for Retention and Persistence to Graduation

The ET advisors have identified few unique advising strategies that worked better for retention and graduation for Engineering Technology students. These strategies are described below:

- Personalized advising: Many ET advisors believe that personalized advising by the same advisor appears to work well for ET students. When an advisor take time to talk with students, show that s/he cares about the student, connect them as a person and believe in them, they in turn become more interested in their education and stick around.

- Being proactive is key: While some students will reach out to their advisor when concerns or questions arise, the students most at risk are those that will not. This tends to be true for first-year and re-entry students who either don’t understand the process and procedures of the success coaching team or are unwilling to admit that they are struggling. By proactively identifying these students and checking on progress, discuss resources, and answer any questions that may have can go a long way to retain these students in the program. Robust technology and data analytics makes it possible to do everything from tracking first-generation student progress to triggering alerts when students miss classes. Analytics can make it easier to drive at-risk students to services or other supports before it’s too late.

- Provide support in normalizing academic challenges: Many freshmen and at-risk students may not be familiar with the feeling of having to put in a lot of effort in their college work, so this is a change for them when they start college. In this situation, getting students physically in front of you (not email) to talk about their progress in courses and honest conversations about what distractions they may be dealing with, what issues they may be facing outside of class is important. The more students can open up to the advisor the better they can help students by offering solutions, options and resources.

- Keep them motivated with career prospects: Be the campion of student success. Regularly complimenting students (in email, in person) on their accomplishments such as from getting off of probation, getting GPA above 3.0, getting through a class they were worried about, Dean’s List, Semester Honors, etc. boost students self-confidence and resiliency. Showing students how the classes they take have real-world application and how the curriculum prepares them for the many career opportunities help students to be persistent in the program and make them resilient toward graduation.

- Early semester progress reports on grades and attendance, Midterm grades, semester campaigns targeted at students near graduation thresholds, and mandatory advising each semester all assist in both retention and graduation because the students must see their advisor at a few times per year. Also, giving students a task to bring to their advising meetings gets them involved and can facilitate other questions about the program (“for instance my email to students tells them to look at courses for the next semester and come with a proposed schedule in hand”).

The advisors also pointed out few strategies that seems least effective for Engineering Technology students. Engineering Technology programs are highly completive programs and most students enter in engineering program are high performing students in high school. But when at college they hit their first roadblock – whether it is failing a test, an incomplete homework, or a general lack of confusion in a course – they panic. Because these students are not used to experiencing failure, they are not sure how to react to it; many of them start to question their own intelligence and their future in the program. So, telling these at-risk students that it only gets harder, so they better work harder does not work. Asking them to change majors if they do not experience immediate success, especially in math also not an effective way to advise these students. In most cases, these type of advices just work as an agent to drive students away from the program. In this situations, helping students to visit a tutor or to see a faculty member so that they get the support and assistance that they need to actually be successful in their courses help students stay in the program and graduate. As on advisor mentioned “Doing anything to make the students feel like they are dumb when they don’t do well on an exam immediately shut them down and shut people out. Lecturing or expressing disappointment/frustration doesn’t help the student, even though it might be out natural reaction at times. We want them to come to us, not shut us out, so we need them to feel like we’re a reliable, trusting, and understanding resource for them”. Being passive, ignoring students’ complaints or concerns, and limited knowledge about the curriculum and departmental procedures and practices are also detrimental to ET students’ persistence in the program. Advising technology such as mass emails and bulletins posted are good ways to get information out to the Engineering Technology students as a whole, but they are not as effective as face to face interactions.

Advisors’ recommendations for faculty advisors

As more and more ET programs now require faculty members to advise students, it will be beneficial for faculty member to partner with advisors and learn the art of advising. The survey asked the advisors to provide suggestions for ET faculty advisors so that they can be more effective in advising. Following are the suggestions provided by the advisors

- ET faculty advisors should take time to find out what is really going on with a student. Faculty advisor should be proactive and support students with difficult issues. Skipping class is a symptom of the real problem. Intentional contact with students with the goal of developing a caring and beneficial relationship typically leads to increased academic motivation and persistence. One advisor mentioned “Not all students are alike. Some need very little advising and do well. Others need more guidance throughout their tenure as students. Have a tool available to indicate this with clarity. Show that you care about them. Be patient. Be friendly. Be flexible. We are training people to become engineers. Help them cross the finish line”.

- When ET students faces academic challenges, sometimes they are hesitant to visit the faculty as they see it as a failure on them. What is intuitive to faculty is new to students. They may not see the relevance or meaning in the content or courses they have to take. Explaining it to them in a way that relates understanding is key to build a supportive relationship. They are not questioning your knowledge or authority, but rather seeking information and guidance. Getting to know the students as much as possible besides just “how are classes going” is the gateway to having more open and honest conversations about their progress in school.

- It is beneficial to faculty advisor to understand as much as possible about all programs and the department as a whole. Faculty advisor also should be knowledgeable about courses, curriculum, policies, strategies, and an in-house procedure. They should also be aware of any changes to the program and relay that information to students as soon as possible.

Conclusion

Effective academic advising is crucial to the long term success of students in Engineering Technology disciplines. The academic advisor is the liaison or link between the students and the university. It is believed that the success of a university is based on the success of its graduates. Given the projective shortage and demand for future engineers in the United States, it is vital that the retention rate and interest in pursuing Engineering disciplines is increased. With that said, academic advising can make a huge difference in the lives and persistence to graduation for engineering students. Academic advisors can intervene with students who are considering dropping out and assist them with developing a success plan that could “right the ship”, providing a platform for the student to stay in school and excel and feel positive about him/her self.

This paper summarizes results of a national survey of ET advisor to learn best of advising ET students. The paper describes the key characteristics of ET advisors, their roles and responsibility, computer tools used for advising, commonly used successful ET advising models, and effective advising strategies that help ET students’ retention and persistence toward graduation. The overall contribution of this study to ET body of knowledge is that it provides ET academic advisors a set of best practices for ET student success. The findings of the study will also benefit ET faculty members, who directly or indirectly advise students, by sharpening their advising practices. One key limitation of the study is that the results are summarized based on limited sample size (22) and a larger sample would provide more confidence on the findings. However, studies focusing on retention in engineering and other disciplines have similar findings which validate the results of this study. (REF)

The literature suggest that early intervention of academic advising is critical. Therefore, it is paramount that freshman engineering and engineering technology students are greeted with a trained advisor as soon as they step foot on the campus. This will help them make the adjustment of a new environment which is filled with many first times experiences. Many students who go to college need to learn how to make good academic decisions, as good academic preparation does not always predict success academically. Academic advisors have a great opportunity to intervene and provide guidance that students need to navigate what often can be viewed as a complex maze.

References

- Bloom, J. L., B. L. Hutson, and Y. He. 2008. The appreciative advising revolution. Stipes: Champaign, IL.

- Cairncross, Caitlin, Tammy VanDeGrift, Sharon Jones, and Lindsay Chelton. 2015. “Best Practices for Advising At-Risk First-Year Engineering Students.” 7th First Year Engineering Experience (FYEE) Conference. Roanoke, VA.

- Corts, D.P., J.W. Lounsbury, R.A. Saudargas, and H.E. Tatum. 2000. “Assessing undergraduate satisfaction with an academic department: A method and case study.” College Student Journal 399-409.

- Earl, W.R. 1987. “Intrusive advising of freshmen in academic difficulty.” NACADA Journal, 8 27-33.

- Gerdes, H., and B. Mallinckrodt. 1994. “Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention.” Journal of Counseling & Development 281-288.

- Habley, W.R. 2004. The Status of Academic Advising: Findings from the ACT Sixth National Survey. (Monograph No. 10). Manhattan, KS: NACADA.

- Hester, E.J. 2008. “Student evaluations of advising: Moving beyond the mean.” College Teaching 35-38.

- Marcus, J. 2012. ” High dropout rates prompt engineering schools to change approach.”

- Marra, R., K. Rodgers, D. Shen, and B. Bogue. 2012. “Leaving engineering: A multi-year single institution study.” Journal of Engineering Education 6-27.

- Meyer, M. and Marx, S. 2014. ” Engineering dropouts: A qualitative examination of why undergraduates leave engineering.” Journal of Engineering Education 525-548.

- Robbins, R. 2013. Implications of advising load. In Carlstrom, A., 2011 national survey of academic advising. (Monograph No. 25). . Manhattan, KS: National Academic Advising Association.

- Thompson, D.E., B. Orr, C Thompson, and K. Grover. 2007. “Examining students’ perceptions of their first-semester experience at a major land-grant institution.” College Student Journal 640-648.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal