Evaluation of low-cost housing provision and delivery in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Social Policy |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3994 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Evaluation of low-cost housing provision and delivery in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Introduction

Housing greatly influences any individuals’ living conditions. It has a lot to do with their quality of life because increasing the housing performance and meeting the occupants’ economic requirement will ultimately promote their well-being, safety, comfort, satisfaction and productivity (Olanrewaju, et al. 2018). In short, a house is more than just a basic shelter to most people; it can provide various positive experiences. However, many countries in the world such as the UK, the US, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Nigeria, Indonesia and South Africa have very unaffordable housing (Demographia 2017; Osman, et al. 2017). Malaysia is also one of the countries that has expensive housing where it has created a severe housing shortage problem (Department of Statistics 2017). In response to such a situation, the Malaysian government initiated various programs and policies that could increase the housing stocks and homeowners under the “Zero Squatters Policy”.

It is worth analyzing the policies and schemes related to low-cost housing and their current performance because the demand for such a housing has increased steadily, especially in a more urban area (Zaid 2015). Looking into affordable housing is also important because the majority of Malaysia’s population belong to this category or, in other words, is eligible for living in such housing units (Idrus & Ho 2008). This paper will evaluate the policies and programs with a particular focus on Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia and its urban agglomeration, “the Greater Kuala Lumpur” which, overall, belongs to the Selangor State. By analyzing from two different perspectives, housing governance and the delivery based on the end users’ point of view, this paper aims to assess the current situation and implications of Malaysia’s affordable housing provision.

Current situation in Kuala Lumpur

Kuala Lumpur is the national capital and the most populous city of Malaysia. It has an estimated population of 1.8 million people as of 2018 in the city proper or in an area of 243 square kilometers (Department of Statistics Malaysia 2018). This makes Kuala Lumpur not only the most densely populated city in Malaysia, but also the only global city in the country that is rapidly growing by attracting huge economic and social movements nationally as well as internationally (Teck-Hong 2012). It also creates an urban agglomeration known as “the Greater Kuala Lumpur” or “Klang Valley,” a region of 2,793 square kilometers where 7.25 million of people reside in a density nearly equal to that of the city proper (Department of Statistics Malaysia 2011).

Kuala Lumpur is characterized as one of the most liveable and safest cities in the world, being ranked the 70th globally by the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Liveability Ranking and the 31st by the Safe Cities Index (The Economist Intelligence Unit 2017). The city as a whole also has a high Human Development Index. These indicators may convey a wholistic picture of Kuala Lumpur, but they do not necessarily provide accurate information concerning the housing situation in the city.

Housing is especially important in a highly urbanized city such as Kuala Lumpur because securing a basic shelter can greatly influence an individual’s daily activities and needs to live in a city (Suhaida, et al. 2010). The reality is that those people who migrate to Kuala Lumpur with limited skills struggle to live on a day to day basis because housing is generally considered as extremely unaffordable and severely burdensome for buyers (Sulaiman, et al. 2016). Various studies similarly reveal that the cost of housing is too high that it has outpaced the increase of incomes and inflation (Real Estate and Housing Developers’ Association Malaysia 2016; Olanrewaju & Woon 2017; Olanrewaju, et al. 2018). The number of houses constructed in this area exceeds 45 percent of the total amount of constructed houses nationally, but the home ownership rate still falls to 53.5 percent, far below the national average (i.e. urban home ownership) of 69 percent (Ministry of Finance’s Valuation and Property Service Department 2009; Samad, et al. 2016).

As a result of the increasing cost of living, renting a house tends to be the alternative to finding a place to settle because owning a house to live in urban areas is not an affordable option for most people, at least not feasible in a short term (Sulaiman, et al. 2016). Moreover, fueled by continuous migration from rural to urban areas and the city’s rapid urbanization, the demand for low-cost housing has also continuously increased (Zaid 2015). It is, therefore, not a surprise that Kuala Lumpur faces serious shortage of low-cost housing units (Bakhtyar, et al. 2013).

The increasing cost of living has been affecting the majority of dwellers in the capital city. According to the Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), up to 27 percent of the households living in the city fail to earn sufficient level of income necessary to afford a minimum acceptable standard of living (Ridzwan & Idris 2018). In other words, about a quarter of Kuala Lumpur’s population constitutes urban-poor households who earn below the living wage. However, it is important to note the differences in the definition of “urban poor”.

A study by Sulaiman et al. (2016) indicates that half of the citizens in Kuala Lumpur is characterized as urban poor, but the definition varies; the study states that urban Malaysians with an income of below RM 2300 per month is generally defined as urban poor, whereas in Kuala Lumpur, specifically, an income below RM 3000 per month is considered an urban poor; they also acknowledge that the Department of Social Welfare defines urban poor as those households with an income below RM 1500 (ibid). Under the status quo, low-cost housing units in Kuala Lumpur are prepared for those households with less than RM 4,000 monthly income, while those in other Malaysian cities are targeted at an income level of RM 1,500 monthly (Zaid 2015). Overall, it is certain that, as the cost of living in Kuala Lumpur continuously increases, the needs for low-cost housing also increase.

“Zero Squatters Policy” and the housing governance

To begin with, the federal and state governments have provided numerous low-cost housing programs and schemes to low and middle-income households across the country, but the provision of those houses has consistently been motivated and followed by a national policy, Malaysia’s “Zero Squatters Policy” (Abdullah, et al. 2017).

Informal settlements or squatter settlements (as the government calls them) in major Malaysian cities have continuously increased as rural communities migrate to urban areas such as Kuala Lumpur, where most of the economic activities concentrate (Teck-Hong 2012). These incoming migrants to cities, however, do not only create new squatter areas but also increase such settlements in the existing ones (Shresta, et al. 2014). The local authorities have continuously controlled against illegal land occupation and, in fact, there are regulations and laws that prohibit people from illegally occupying the state-owned land, but squatters seem to still increase year by year (Murad, et al. 2014).

In response to the increasing number of squatter settlements in urban areas, the state governments implemented a program in 1998 to eradicate those settlements. The 1998 eradication program demanded the Department of Statistics to collaborate with the local authorities to determine and verify the old and new squatter settlements and immediately tear down any squatter settlements built after the 1st January 1998 (Abdul Aziz 2012). This program, however, was later followed by and evolved into the Malaysian “Zero Squatter policy” introduced in 2000; the policy aimed to reduce squatter settlements by ensuring that everyone in the state would legally own a house by year 2005 (Abdullah, et al. 2017). This was the starting point of Malaysia’s low-cost housing provision.

The introduction of the Zero Squatter policy then initiated the creation of the Program Perumahan Rakyat Bersepadu (PPRB), or the Integrated People’s Housing Programme in which residents of the existing squatter settlements were provided with basic utilities such as electricity and water until their relocation were to be completed (ibid). This particular program was initially targeted to reduce the squatter settlements in Kuala Lumpur and other major Malaysian cities. These informal settlements particularly concentrate in the Greater Kuala Lumpur region, comprising about 30 percent of the total population (Shuid 2010).

In the 9th Malaysian Plan (2006-2010), the government continued to focus on reducing the number of squatter settlements and decided to extend the period of the Zero Squatter mission up until 2020. Based on the policy statements and objectives prepared by the government, public and private housing developers were also demanded to continue to provide more low-cost housing units in their development projects. In this sense, the federal government took the lead to create incentives for both the public and private sectors concerning low-cost housing programs (Shuid 2004; Abdullah, et al. 2017). The involvement of private developers in the government-led programs is becoming more and more important for successful low-cost housing initiatives (Idrus & Ho 2008).

Numerous housing schemes were created, as a result. Examples include Perumahan Rakyat 1 Malaysian (PR1MA), Perumahan Penjawat Awam 1 Malaysia (PPA1M), Rumah Wilayah Persekutuan (RUMAWIP), and My Home Scheme and so on (Shuid 2016). Table 1 below briefly summarizes some of the major public housing programs in Malaysia.

Table 1. Public Housing Programs

|

Public Housing Program |

Description |

|

Perumahan Awam Kos Rendah (PAKR) |

The Federal Government provides funding in the form of loan to the state governments to build low-cost houses. |

|

Perumahan Awam Kos Rendah Bersepadu (PAKRB) |

Low-cost flats for rental to overcome the problem of squatters in Kuala Lumpur |

|

Program Perumahan Rakyat (PPR) |

To provide comfortable houses with adequate infrastructure and basic amenities in suitable locations. Implemented to address the increasing demand for affordable housing among the low-income households, particularly in urban areas. |

|

Perumahan Rakyat 1 Malaysia (PR1MA) -(2014) |

– Develop and maintain quality affordable housing for middle income group. – House price between RM 100,000 to RM 400,000 in major cities. |

|

Perumahan Penjawat Awam 1 Malaysia (PPA1M) -(2014) |

Housing for low and middle income civil servants (household income of RM 8,000 and below). Built on government land and priced between 20% and 30% lower than the market price |

Source from: Ministry of Economic Affairs Economic Planning Unit (2013)

As a result of the continuous emphasis on reducing squatter settlements in Kuala Lumpur fueled by the Zero Squatter Policy, the total number of low-cost housing units built by public and private developers increased to some extent (Abdullah, et al. 2017). Under the 8th Malaysian Plan (2001-2005), more than 200,000 or 86 percent of the planned low-cost housing units were actually delivered, of which 51.5 percent were constructed by the public sector, State Economic Development Corporations (Fallahi 2017).

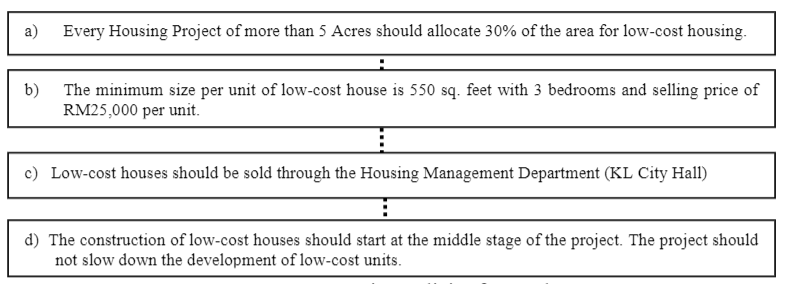

The number of squatter families, however, did not decrease but kept increasing even after the establishments of multiple government-led schemes as well as regulations on the private housing developers to allocate some portion of their housing projects to low-cost units (Abdullah, et al. 2017). As shown in Figure 1 below, the Kuala Lumpur City Hall introduced multiple policies and specifically issued guidelines concerning the provision of low-cost housing units in Kuala Lumpur, but the number of squatters remained high (ibid).

Figure 1. Low-Cost Housing Policies for Kuala Lumpur

Source from: Abdullah, et al. (2017)

Provision of Low-cost Housing and the end users’ point of view

The endless growth of squatter areas has something to do with how the low-cost housing units have been provided to the people. Under the status quo, the provision of low-cost housing is mandatory in Malaysia. Abdullahi & Aziz (2011) briefly summarizes the multiple levels of government involved in the delivery of low-cost housing:

In Malaysia the Federal government provides policy frameworks in general terms. But it is at the state level that the policy is translated into more detailed and strategized. At the state level the policies are expressed in the structure and strategies plans for each state. Finally, at the local government levels the prepared plans are made more detailed with specific requirements elaborations (pp.11).

The local administration carried out by the Kuala Lumpur City hall also mandates that housing developers must allocate 30 percent of their total development projects to low-cost housing in order to gain development approval (Shuid 2016). Such an administrative procedure, however, has brought unintended outcomes to the provision of the low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur. Couple of studies similarly point out that the quality of these low-cost housing tends to be substandard and inadequate as developers merely aim to meet the development’s approval quota (Abdullah, et al. 2017; Sulaiman, et al. 2016).

Moreover, it is not only the construction of these affordable housing units that is characterized as having a poor quality, but it is also the maintenance and service of them that do not meet the occupants’ satisfaction. The study by Sulaiman et al. (2016) reveals that the maintaiance of the low-cost housing units tends to halt or even be totally disregarded not only by the local authorities and developers but also by the government-led low-cost housing programs such as the People’s Housing Program or Projek Perumahan Rakyat (PPR).

Such a problem is attributed to the fact that the government, as recommended by the Malaysian Plan, provides the budget as subsidies to those programs for only five years so, as a result, the local authorities and developers have less incentives to continue to look after the low-cost housing units when the 5-year term ends (ibid). Indeed, there is a time frame or limit of some sort to the governments’ intervention on the housing programs, but the continuous subsidies allocated by the federal government proves to be crucial in the long term delievery of these affordable housing schemes in terms of the financial sustainability (Shuid 2016). Subsidies on the affordable housing units are supposed to alleviate the occupants’ burden so that they can attain acceptable level of dwelling, but the current situation hardly caters to such needs.

Even though the housing providers do have the motivation to carry out the maintainance and service, they tend to be financially burdened because the low-income tenants cannot pay for the energy and basic utilities fees in the first place (Sulaiman, et al. 2016).

Overall, it is arguable that low-cost housing is prepared and designed in a way that they can simply accommodate former squatters so that the state governments will be able to achieve the Zero Squatter mission by 2020 (Tan 2011). Abdullah et al. (2017) argues that the government does not have a specific policy to reduce squatter settlements other than merely increasing the number of low-cost housing units, thereby ignoring various factors that tend to be important for the provision of such a housing in a long-run. As a result, many of the affordable housing programs and schemes face challenges such as “the mismatch between demand and supply, house price increase, lack of integrated planning and implementation, poor maintenance, and insufficient amenities” (ibid).

This view is consistent with what Zaid (2015) states in his study: the housing affordability definition and its delivery in Malaysia overlook important matters such as the long-term operational costs (i.e. utility services and maintenance) and occupants’ satisfaction (i.e. construction quality). Thus, even though the low-cost housing programs do sell or rent the units below market price value backed up by the government’s subsidies, the overall quality of them tend to be substandard (ibid). Merely increasing the housing supply will not automatically make the houses affordable as a whole (Poon & Garratt 2012).

Discussions and conclusion

The current situation of low-cost housing provision in Malaysia therefore has serious problems not in the production of the units but in how they are allocated to the low-income people who are eligible for owning such houses (Shuid 2011). In other words, the programs fail to fully consider the end users’ satisfaction and needs that they end up creating a mismatch between the supplies and the demands (Abdullah, et al. 2017). The side effects of such a tendency can be seen as the following problems. There seem to be a huge gap in what people need and what the housing programs supply.

Firstly, the numerous low-cost housing schemes (existing or planned ones) in Kuala Lumpur create extra demands and competition between public and private developers which, ultimately, drive the housing prices to increase (Lean & Smyth 2012). The increased number of housing programs also create significantly varying definition of “affordable” housing as well (Siew 2017). Having more housing options may be important for the future residents, but, currently, the wide variety of the programs tends to cause more confusion to the public (Shuid 2016).

Secondly, the mismatch between the tenants’ needs and the providers’ intention can be seen as the oversupply of mid-income and luxury housing. In Kuala Lumpur, specifically, the housing developers mostly construct housing for medium income and above, and do not comply with the City Hall’s requirements of providing 30 percent of the total units as low-cost ones (Bakhtyar, et al. 2013). This situation seems to exacerbate the low-income group. According to a study by Zainon, et al. (2017), 85.7 percent of the low-income groups in Kuala Lumpur have difficulties in accessing these housing schemes in the first place because they cannot get housing loans due to the expensive housing prices, interest rates and the strict lending guidelines.

For more than a decade, the federal and state governments altogether have created numerous low-cost housing schemes that are designed to accommodate residents in the low-income groups. But the current situation as discussed above seems to indicate that those programs are essentially government interventions that merely focus on eradicating the informal settlements around the urbanized areas. The government’s Zero Squatter Policy aims to reduce such dwellers but in actuality the regulations and even programs simply authorize the local authorities to demolish the existing informal housing and ultimately relocate the squatters. To borrow Yap’s (2015) words, the forceful demolition and eviction cannot solve the fundamental problems concerning squatter settlements because those people will end up finding and creating new ones in the city, or add up to the existing ones under worse conditions.

Despite the government’s effort to encourage people to own their own houses, Malaysia is now said to be facing a potential housing crisis where the young generations cannot own a house or, to be more precise, cannot afford to purchase a house in their 20s or 30s (Lim 2017). As homeless generations seem to be emerging even today, it is necessary for the governments of all levels to review how the low-cost housing programs should be delivered in a long term, based on what most people need.

Works Cited

- Abdul Aziz, F., 2012. The investigation of the implications of squatter relocations in high risk neighbourhoods in Malaysia, Newcastle, United Kingdom: Newcastle University.

- Abdullahi, B. C. & Aziz, W. N. A. W. A., 2011. Pragmatic Housing Policy in the Quest for Low-income Group Housing Delivery in Malaysia, Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia http://jice.um.edu.my/index.php/jdbe/article/view/5305/3098 [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Abdullah, Y. A., Kuek, J. N., Hamdan, H. & Zulkifli, F. L. M., 2017. Combating Squatters in Malaysia: Do we have adequate policies as instrument?. Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners, 15(2), pp. 25-36. http://planningmalaysia.org/index.php/pmj/article/view/263/236 [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Bakhtyar, B., Zaharim, A., Sopian, K. & Moghimi, S., 2013. Housing for Poor People: A Review on Low Cost Housing Process in Malaysia. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development, 9(2), pp. 232-242. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267034869_Housing_for_Poor_People_A_Review_on_Low_Cost_Housing_Process_in_Malaysia [Accessed 8 January 2019].

-

Demographia, 2017. 13th annual Demographia international housing affordability survey: 2017 rating middle-income housing affordability.. [Online]

Available at: www.demographia.com/dhi.pdf [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2011. Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristic Report 2010. [Online] Available at: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=117&bul_id=MDMxdHZjWTk1SjFzTzNkRXYzcVZjdz09&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09 [Accessed 8 January 2019].

-

Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2018. Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur. [Online]

Available at: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cone&menu_id=bjRlZXVGdnBueDJKY1BPWEFPRlhIdz09

[Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Department of Statistics, 2017. Current population estimates, Malaysia, 2016-2017. [Online] Available at: https://www.dosm.gov.my/ [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Fallahi, B., 2017. Evaluation of National Policy Toward Providing Low Cost Housing in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), pp. 9-19. DOI: 10.20472/SS2017.6.1.002

- Idrus, N. & Ho, C., 2008. Affordable and quality housing through the low cost housing provision in Malaysia, Malaysia: Proceedings of Seminar of Sustainable Development and Governance. .

- Lean, H. & Smyth, R., 2012. Reits, interest rates and stock prices in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Society, 13(1), pp. 49-62.

- Lim, I., 2017. Warning of ‘homeless generation’, HBA wants Rent-to-Own for middle class too. Malay Mail Online, 4 April, pp. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/warning-of-homeless-generation-hba-wants-rent-to-own-for-middle-class-#ugTQjedFcsJrEZx9.97. [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Ministry of Economic Affairs Economic Planning Unit , 2013. Laporan kesejahteraan rakyat Malaysia. [Online] Available at: http://www.epu.gov.my/documents [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Ministry of Finance’s Valuation and Property Service Department, 2009. Property market status report. Government Printer, Kuala Lumpur.

- Murad, M., Hasan, M., Islam, M. & Alam, M., 2014. Socio economic profile of the low income and poor communities in Kuala Lumpur city, Malaysia. International Journal of Ethics in Social Sciences, 2(1), pp. 113-130.

- Olanrewaju, A. et al., 2018. Factors Affecting Housing Prices in Malaysia: Analysis of the Supply Side. Planning Malaysia: Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners, 16(2), pp. 225-235.

- Olanrewaju, A. & Woon, T., 2017. An exploration of determinants of affordable housing choice. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 10(5), pp. 703-723.

- Osman, M., Bachok, S., Shuid, S. & Khalid, N., 2017. Factors influencing housing prices among local people: a study in Perak, Malaysia.. Advanced Science Letters, 23(1), pp. 165-168.

- Poon, J. & Garratt, D., 2012. Evaluating UK housing policies to tackle housing affordability. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 5(3), pp. 253-271.

- Real Estate and Housing Developers’ Association Malaysia, 2016. MIER’s residential property survey report 4Q 2015. [Online] Available at: http://rehda.com/ [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Ridzwan, A. & Idris, A. N., 2018. Urban poor constitute a quarter of KL households. The Edge Financial Daily, 29 March, pp. http://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/urban-poor-constitute-quarter-kl-households.

- Samad, D. et al., 2016. Malaysian Affordability Housing Policies Revisited. MATEC Web of Conferences IBCC 2016, 66(00010). DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/20166

- Shresta, R., Tuladhar, A., Zevenbergen, J. & Banskota, M., 2014. Decades of struggle of space: about the legitimacy of informal settlements in urban areas.. 25 ed. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: International Federation of Surveyors Congress.

- Shuid, S., 2004. Low medium cost housing in Malaysia: issue and challenges. Asia Pacific Network for Housing Research Conference (APNHR).

- Shuid, S., 2010. Low Income Housing Allocation System in Malaysia: Managing. 22nd International Housing Research Conference , Volume WS-09.

- Shuid, S., 2011. Role of the state and market in low cost housing provision in Malaysia: The case study of open registration system for low cost house buyers, Wales: Cardiff University.

- Shuid, S., 2016. The Housing Provision System in Malaysia. Habitat International, 54(3), pp. 210-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.021

-

Siew, R., 2017. Affordable housing in Southeast Asia. [Online]

Available at: https://theaseanpost.com/article/affordable-housing-southeast-asia

[Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Suhaida, M. et al., 2010. A conceptual overview of housing affordability in Selangor, Malaysia. International Journal of Social, Human Science and Engineering, 4(12), pp. 287-289.

- Sulaiman, F. C., Hasan, R. & Jamaluddin, E. R., 2016. Users Perception of Public Low Income Housing Management in. Procedia Social and behavioral Sciences, Volume 234, pp. 326-335.

- Tan, T., 2011. Sustainability and housing provision in Malaysia. Journal of Strategic Innovation & Sustainability, 7(1), pp. 62-71.

- Teck-Hong, T., 2012. Housing satisfaction in medium- and high-cost housing: The case of Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Habitat International, 36(1), pp. 108-116.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2017. Safe City Index Security in a rapidly urbanising world. [Online] Available at: https://dkf1ato8y5dsg.cloudfront.net/uploads/5/82/safe-cities-index-eng-web.pdf [Accessed 8 January 2019].

- Yap, k. s., 2015. The enabling strategy and its discontent: Low-income housing policies and practices in Asia. Habitat International, 54 (DOI: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.026).

- Zaid, S., 2015. Is Public Low-Cost Housing in Malaysia really affordable? Measuring Operational Affordability of Public Low-Cost Housing in Kuala Lumpur, s.l.: International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

- Zainon, N. et al., 2017. Factors Affecting the Demand of Affordable Housing among the Middle-Income Groups in Klang Valley Malaysia. Journal of Design and Built Environment, Issue https://umexpert.um.edu.my/file/publication/00008434_155985_70407.pdf, pp. 1-10. [Accessed 8 January 2019].

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal