Investigation of Effectiveness of Clozapine

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Sciences |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3648 words | ✅ Published: 15 Sep 2017 |

Catarina Scott-Beaulieu

Abstract: (250)

Background: Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic used for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. It is effective in treating the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia with a reduced chance of extrapyramidal side effects compared with other typical antipsychotics. Clozapine is known to have cardiac side effects including, but not limited to, myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Approximately 75% of cases, of clozapine-induced myocarditis, occur within the first month of titration, highlighting the need for monitoring.

Objectives: To assess the extent to which the monitoring guidelines for myocarditis, at a London mental health trust, are being followed.

Method: Patients who were registered with ZTAS from June 2014 to October 2016, at the trust, were identified. Data was collected based on the audit tool created from the guidelines. Using the patient notes and laboratory data, found using the trusts operating systems, data was collected and stored in the audit tool.

Key findings: The monitoring standards were met for full blood count in the week prior to initiation and in week 3. No other standards were met.

Conclusion:

Introduction: (500-1000)

Clozapine is the first atypical antipsychotic created and is used in treatment-resistant schizophrenia, which is defined as a lack of or an inadequate response to at least two antipsychotics.[1] It is a dibenzodiazepine derivative antipsychotic and interferes with dopamine binding with a strong affinity for D4-dopaminergic receptors and 5-HT2a serotonergic receptor affinity [2], in addition it has an anticholinergic effect and antagonizes histaminergic receptors. [3, 4]

Clozapine is useful in treating both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia [4] and is less likely to cause extrapyramidal side effects when compared to first generation ‘typical’ antipsychotics such as haloperidol[5, 6]. It has also been shown to significantly reduce the suicidal behaviors in schizophrenic patients [1, 7].

However, it is not used as a first line treatment due to its extensive side effect profile, most recognized being agranulocytosis which occurs in approximately 1% of patients in the first year of treatment [8, 9], explaining the need for regular, mandatory hematological tests for the duration of clozapine treatment. Other side effects include fever [4], metabolic effects and seizures.[4, 6, 10]

Agranulocytosis, however, is not the only potentially fatal side effect of clozapine use. There is an increasing number of clozapine-related cardiac complaints reported in the literature, resulting in cardiac effects from clozapine treatment having become more recognized over the past few years. [5, 7] Whilst tachycardia is a common side effect it can be indicative of other, potentially more serious, cardiac effects such as cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. [9]

Myocarditis is an inflammatory process of the myocardium, which is often of viral aetiology but may also include bacterial, fungal and drug-induced.[11, 12] The condition presents with a wide range of symptoms such as chest discomfort, flu-like symptoms and abnormal vital signs [9] and most are non-specific.[2] Reported cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis range from 0.15% to 1.2%,[5, 8, 13-15] with the highest incidence being reported in Australia, >1%. [16] Time to onset varies, but over 75% of cases occur within the first month of treatment. [12, 16-18]

Endomyocardial biopsy was the gold standard for diagnosing myocarditis, but the procedure has only limited sensitivity and specificity. It was by proposed Ronaldson et al.[18] in 2011 that combining C-reactive protein (CRP) and troponin T/I would give a sensitivity for clozapine-induced myocarditis of 100%. This is a less invasive method of diagnosis, with a higher specificity and sensitivity for myocarditis and has led to the current guidelines that are in place for the monitoring of clozapine treatment.

Whilst clozapine-induced myocarditis is still rare, the need for consistent monitoring within the first month of treatment is needed to ensure any possible cases are detected early, allowing for prompt treatment, increasing the chances of a better outcome for the patient.[1]

This audit aims to assess the extent to which the monitoring guidelines for myocarditis, at a London mental health trust, are being followed. Assessments will explore the extent to which the recommended additional blood tests, CRP and troponin, are being completed and the extent to which the advised echocardiogram (ECG) are being followed. Additionally, it will aim to check to see if a clinician is checking the above objectives and assess the extent to which the nursing staff are asking the patients about signs and symptoms of myocarditis.

Method: (500-1000)

This audit was designed to investigate the extent to which the monitoring requirements, in regards to clozapine initiation and titration within the first four weeks of treatment, at a London mental health trust had been completed. The monitoring requirements audited were specific to the detection and diagnosis of myocarditis. Data collection occurred between October 2016 and February 2017. It is a baseline, retrospective audit of case notes and laboratory data. As per the Health Research Authority regulations, this audit did not require ethical approval.

Audit standards and audit tool

The standards used in this audit were taken from the trust’s clozapine guideline, which can be found in table 3. The monitoring requirements for the detection of myocarditis involve an ECG, vital sign monitoring (pulse, blood pressure, temperature) and CRP and troponin T blood tests. These had to be completed prior to initiation and weekly for the first four weeks after initiation. It is also necessary for clinicians to verify the results of the CRP and troponin T tests, and for the nurses or clinicians to check if the patient has had any signs or symptoms of myocarditis. For the purpose of this audit, criterion 1 and 3 (table 3) will be met if the results of the investigations were documented. Criterion 2 (table 3) will be met if the clinician has made specific reference to CRP and troponin T tests in the patient notes, criterion 4 (table 3) will be met if there is specific reference to questions being asked about myocarditis symptoms. An audit tool was created using the specified monitoring requirements mentioned in the clozapine guideline, a template of the audit tool can be found in table x.

Identifying patients to be involved in the audit

Clozapine patients require regular and frequent prophylactic blood tests in order to initiate and continue treatment. As such, there is a mandatory need for patients to be registered to a clozapine monitoring service database, which collects and stores the results from the weekly blood tests. Zaponex Treatment Access System (ZTAS) is the monitoring company that was used by the trust. ZTAS provided a list of patients who were registered with them whilst under the care of the trust, from June 2014 to October 2016. This resulted in a total of n=57 patients. The patients were selected to be used in the audit after they adhered to the inclusion criteria, which are shown below.

Data Collection

Data was collected using various information sources at the hospital. Data on haematological tests were collected systematically from ZTAS, bloodresults.co.uk, and the trust clinical portal. ZTAS and bloodresults.co.uk offered information on the standard full blood count (FBC) monitoring that takes place weekly. The trusts clinical portal was used to collect information on other heamatological tests, CRP and troponin T; this source was also used to check any other available FBC test results. RiO, the trust’s operating system, was used to collect information on the other standards being measured in this audit (criterion 2, 3 and 4)(table 3). The data collected was stored in the audit tool. ( table x)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion of the patients in the audit required them to have been registered with ZTAS at the trust between June 2014 and October 2016. It was also necessary for the patient to have started some (at least two) of the required monitoring standards prior to initiation. Prior monitoring requirements included an ECG within a maximum of 3 months prior to initiation and FBC, CRP and troponin T within 10 days of the initiation date. Vital sign monitoring such as pulse, blood pressure and temperature were included if they had been completed a maximum of 7 days before initiation.

Patients were excluded from the audit if they had been transferred from another trust and were already on a controlled clozapine treatment regime.

Method of data analysis

Data analysis and statistical analysis was completed using Microsoft Excel 2013.

Overview

As stated previously, clozapine is associated with an increased risk of myocarditis, which has been fatal in some cases. Preventative monitoring measures for myocarditis are advised at this trust. Baseline troponin T, CRP and ECG should be done prior to beginning treatment and then weekly for the following first four weeks after initiation. These measures are specific in identifying myocarditis, but should also be done in concordance with standard monitoring during treatment. The standard monitoring procedures include pulse, blood pressure and temperature to be completed every other day and FBC weekly. These monitoring procedures are necessary in helping to diagnose myocarditis; symptoms of myocarditis are non-specific, but tend to indicate the presence of an infection (fever) or simulate myocardial infarction (chest pain). Nurses and practitioners are advised to question patients on the appearance of any side effects similar to myocardial infarction to help ascertain if they could have myocarditis.

Patient demographics and study data

In total, n=57 patients were reviewed. Of those, n=3 patients were excluded based upon the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the method. Of the remaining n=54 patients, n= 6 (11.11%) patients did not initiate clozapine treatment, but n=5 were included in the audit as they had started the monitoring required prior to initiating treatment. Reasons for not initiating treatment are outlined in table 1. A total of n= 3 patients ceased clozapine treatment in week one (n=2) and during week three (n=1); one patient was persistently tachycardic, one patient refused to continue treatment and one patient was severely hypotensive.

The patient group (n=53) was predominantly male 66% (n=35), 34% (n=18) were female. The mean age of patients who initiated treatment (n=48) was 34.42 years old, with the youngest patient age being 16.92 years old and the oldest being 65.21 years old.

Length of treatment was calculated as the time between a patient commencing clozapine treatment and either ceasing clozapine or the end of the audit period. A total of n=10 patients were excluded from the calculation, as they either did not start treatment or the end of treatment time was not able to be calculated; reasons for exclusion are explained in table 2. The mean length of treatment was 387 days ±268, with the shortest length of treatment being 1 day and the longest being 873 days. Of the 53 patients involved at the start of the audit, 65% (n=35) were initiated on an inpatient basis; this means the patients were initiated at the hospital, on a ward.

ECG monitoring

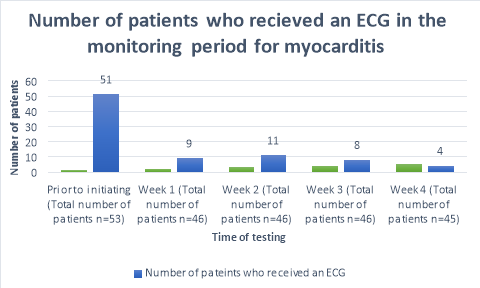

A baseline ECG had been completed in 96% (n=51)(Figure 1) of patients within 3 months prior to the commencement of clozapine. One patient refused to have an ECG prior to initiation. The percentage of patients who received ECG’s decreased to 20% (n=9), 24% (n=11), 17%(n=8) and 9% (n=4) of patients for the following 4 weeks after commencement respectively. A total of 41 out of 45 (Table 4) patients did not receive an ECG in week four of clozapine titration. During week one, a patient complained of flu like symptoms and was given an ECG to rule out myocarditis; likewise, one patient during week three was given an ECG after complaining of centralized chest pain.

Temperature monitoring

The quantity of patients who had recorded temperatures fluctuated through-out the weeks, being highest in week two of monitoring (n=. Week four had the lowest recorded amount of temperature monitoring of all 5 weeks at patients 69% (n=31) (table 4). In week one, n=2 patients refused to have measurements taken.

Pulse and blood pressure monitoring

The amount of patients who did not receive BP monitoring was highest in the week prior to initiating clozapine (n=13) and in week four (n=13). The highest proportion of patients who had their blood pressures taken occurred during week one at 96% (n=44 ), with 63% (n=29) of them having their blood pressure taken once and 34% (n=15) having their blood pressure taken twice (one reading measured whilst lying or sitting and one reading measured whilst standing). Week four had the highest proportion of patients who did not have their pulse measured at 29% (n=13) (table 4). One patient was discontinued from clozapine after one day of treatment when the BP check revealed them to be extremely hypotensive, in conjunction with a rapid pulse.

Full blood count monitoring

FBC monitoring occurred in the highest proportion of patients throughout the monitoring period; 100%, 98%, 93%, 100% and 96% respectively.

CRP and Troponin monitoring

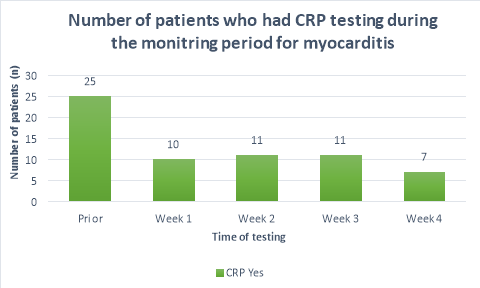

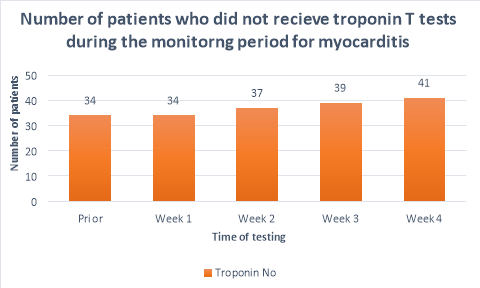

The majority (>50%) of patients did not receive CRP or troponin T blood tests throughout the duration of the monitoring period. Figure 2 shows a substantial decrease in the number of patients who had CRP tests prior to initiation (n=25) and the following weeks (n=10, n=11,n=11, n=7 respectively). A large propotion of patients (84%, n= 38) did not receive CRP blood tests during their fourth week of clozapine treatement. The number of patients who received troponin T tests were less than those who received CRP tests. Only 36%(n=19) of patients received troponin T tests prior to initiation, reducing to 26%(n=12), 20%(n=9), 15%(n=7) and 9%(n=4) in the following four weeks after initiation respectively. There were n=14 patients who had no CRP or troponin T tests throughout the entirety of the monitoring period. There were no patients who had weekly CRP and troponin T tests throughout the duration of the mointoring period.

Other monitoring parameters

In total, the number of patients who had their CRP and troponin checked by clinicians was less than 100% in all cases (69% (n=9), 75% (n=9), 56% (n=6) and 63% (n=5) for weeks one through four respectively). Due to the lack of data regarding criterion 4 (table 3), there are no results available to be discussed.

Summary of main findings

FBC monitoring requirements were met in the week prior to monitoring and in week three. All other standards were not met in any of the five weeks. Over all, there was a better outcome seen in the week prior to initiation for most of the standards. CRP and troponin T tests were completed in less than 50% of patients throughout the five weeks measured. Likewise, excluding the week prior to initiation, less than 50% of patients received an ECG for weeks one to four.

Limitations

Study data was collected using patient notes and the trust’s clinical portal, data was therefore reliant on the relevant health care professional entering the information onto the systems. Consequently, the lack of data could be attributed to the lack of documentation of the monitoring, as opposed to the lack of monitoring all together, especially in regards to criterion 4 (table 3). No useful results could be drawn for criterion 4 and criterion 2 may have also been significantly affected by a lack of documentation.

The sample size of this audit was small (n=53), any conclusions drawn from this data may not be relevant to a larger sample size. However, in future studies, a larger sample size could be used, if this is not possible the audit could be expanded to include other trusts.

Results could also be affected if the patient refused to have the relevant monitoring required, as advised in the trust’s clozapine guidelines.

This audit is the first one to be completed at this trust, therefore it cannot be compared to any previous data. However, the results are being measured against set standards (table x) and can be used to compare to future audits.

Results in context

Clozapine is highly effective in the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia; it reduces the risk of suicidal behaviours[5, 6]and it is effective in the treatment of both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[1] It is not widely used due to its extensive side effect profile [8], most recognised being haematological disorders, such as agranulocytosis and neutropenia which have strict monitoring protocols in place.

However, cardiac side effects of clozapine treatment have become more widely recognised over the past few years.[5] Myocarditis is an inflammatory condition of the myocardium, which is normally attributed to viral aetiology. Clozapine-induced myocarditis is a rare, but potentially fatal result of treatment. Over 75% of cases occur within the first month of treatment, making it important to monitor for myocarditis during the first four weeks of treatment.[2, 14-16]

A study by Ronaldson et al.[18] developed an evidence-based monitoring tool, based on 75 cases and 94 controls for routine monitoring up to 28 days. It suggested that an ECG, CRP and troponin I/T should be completed at baseline, with routine vitals every other day. CRP and troponin I/T tests should also be repeated on days 7, 14, 21 and 28. This study proposes that combining CRP and troponin tests provides a 100% sensitivity for myocarditis. The trust’s clozapine guidelines also suggest the same monitoring protocol, with the addition of an ECG every week, for the first four weeks.

Individuals with schizophrenia have a 20% shorter life expectancy than that of the general population and a greater vulnerability to several illnesses (diabetes, coronary heart disease).[19] Due to the nature of the illness and the heightened health risks associated with schizophrenia and the antipsychotic medications used in its treatment, it is important to adhere to the relevant monitoring protocols.

It is evident, from the results, that the proposed guidelines for the monitoring of clozapine-induced myocarditis are not being met. Likewise, a number of studies have shown a poor adherence to standards in the monitoring of antipsychotic medications.[20]

Physicians may have doubts about the relevance of monitoring, or feel that it is not necessary as the incidence of myocarditis is very low; rate of incidence occur in approximately 0.15-1.2%[1, 13, 21] of patients. If we consider other medications with stringent monitoring protocols, such as insulin, due to health care professional’s awareness of this medication and the implications if the standards are not met, there is often a higher standard of monitoring.

There may also be an implication of cost; extensive monitoring is often expensive, making it appear to be an unnecessary expense, particularly when the chances of myocarditis occurring are very low.

Health care professionals may have a lack of awareness of the need for the monitoring of myocarditis, and the implications if these are not met. The incidence of fatality due to clozapine-induced myocarditis can be as high as 50%[1], making it important to abide by the set guidelines. The monitoring guidelines are made to reduce the harm caused to patients and reduce the possibility of fatalities. However, a delayed diagnosis could result in poorer outcomes for the patients.[1] The standards allow for earlier detection and diagnosis of myocarditis, reducing the chance of poorer outcomes.

The results of this audit indicate a need for an increased awareness of clozapine-induced myocarditis among health care professionals. This would improve the clinicians’ awareness of the need for the monitoring of myocarditis and highlight the implications if the standards are not met. A standardised questionnaire could be created to monitor the signs and symptoms of myocarditis and be used by nurses to document the results, this could be incorporated into the clinical notes.

This baseline audit emphasises the need for future re-audits, to evaluate whether the standards have improved.

Table 1:

|

Reasons for not initiating treatment |

Number of patients (n) |

|

Consistent amber results |

1 |

|

Patient changed mind/ refused |

2 |

|

Previous health conditions made the patient unsuitable to start clozapine |

2 |

|

Unknown |

1 |

|

Total |

6 |

Table 2:

|

Reasons for not being included it length of treatment calculation |

Number of patients (n) |

|

Never initaited clozapine |

6 |

|

Patient transferred to another trust |

2 |

|

Patient returned to country of origin (unknown if they continued treatment) |

2 |

|

Total |

10 |

Table 3:

|

Policy |

|||||

|

Title |

Clozapine Guide Trust-Wide Medication Policy |

||||

|

Date |

July 2016 |

||||

|

Local/National |

Local |

||||

|

Standard Setting |

|||||

|

Criterion 1 |

Criterion 2 |

Criterion 3 |

Criterion 4 |

||

|

Criterion |

Full blood count, including troponin T, CRP, neutrophil and white blood cell count should be done prior to initiating clozapine and then weekly for the first four weeks. |

A clinician verifies the blood test results every week before treatment can be approved. |

An ECG is to be performed prior to clozapine commencement and every week for the first four weeks after initiation of clozapine. |

A nurse or physician enquires about the signs and symptoms of myocarditis weekly for the first 4 weeks of titration. |

|

|

Target |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

|

Exceptions |

None |

None |

None |

None |

|

Table 4:

|

Monitoring |

Prior to initiating (Total number of patients n=53) |

Week 1 (Total number of patients n=46) |

Week 2 (Total number of patients n=46) |

Week 3 (Total number of patients n=46) |

Week 4 (Total number of patients n=45) |

|

ECG |

|||||

|

Yes |

51 (96%) |

9 (20%) |

11 (24%) |

8 (17%) |

4 (9%) |

|

No |

2 (4%) |

37 (80%) |

35 (76%) |

38 (83%) |

41 (91%) |

|

Blood pressure |

|||||

|

Taken once |

36 (68%) |

29 (63%) |

26 (56%) |

25 (54%) |

21 (47%) |

|

Taken twice |

4 (7.5%) |

15 (33%) |

15 (33%) |

12 (26%) |

11 (24%) |

|

Not taken |

13 (24.5%) |

2 (4%) |

5 (11%) |

9 (20%) |

13 (29%) |

|

Temperature |

|||||

|

Yes |

39 (74%) |

38 (83%) |

40 (87%) |

37 (80%) |

31 (69%) |

|

No |

14 (26%) |

8 (17%) |

6 (13%) |

9 (20%) |

13 (31%) |

|

Pulse |

|||||

|

Yes |

42 (79%) |

43 (93%) |

41 (89%) |

37 (80%) |

32 (71%) |

|

No |

11 (21%) |

3 (7%) |

5 (11%) |

9 (20%) |

13 (29%) |

|

FBC |

|||||

|

Yes |

53 (100%) |

45 (98%) |

43 (93%) |

46 (100%) |

43 (96%) |

|

No |

0 (0%) |

1 (2%) |

3 (7%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (4%) |

|

CRP |

|||||

|

Yes |

25 (47%) |

10 (22%) |

11 (24%) |

11 (24%) |

7 (16%) |

|

No |

28 (53%) |

36 (78%) |

35 (76%) |

35 (76%) |

38 (84%) |

|

Troponin |

|||||

|

Yes |

19 (36%) |

12 (26%) |

9 (20%) |

7 (15%) |

4 (9%) |

|

No |

34 (64%) |

34 (74%) |

37 (80%) |

39 (85%) |

41 (81%) |

References

1.Munshi, T.A., et al., Clozapine-induced myocarditis: is mandatory monitoring warranted for its early recognition? Case Rep Psychiatry, 2014. 2014: p. 513108.

2.Aboueid, L. and N. Toteja, Clozapine-Induced Myocarditis: A Case Report of an Adolescent Boy with Intellectual Disability. Case Rep Psychiatry, 2015. 2015: p. 482375.

3.Fineschi, V., et al., Sudden cardiac death due to hypersensitivity myocarditis during clozapine treatment. Int J Legal Med, 2004. 118(5): p. 307-9.

4.Bruno, V., A. Valiente-Gómez, and O. Alcoverro, Clozapine and Fever: A Case of Continued Therapy With Clozapine. Clin Neuropharmacol, 2015. 38(4): p. 151-3.

5.Swart, L.E., et al., Clozapine-induced myocarditis. Schizophr Res, 2016. 174(1-3): p. 161-4.

6.Castle, D., et al., A clinical monitoring system for clozapine. Australas Psychiatry, 2006. 14(2): p. 156-68.

7.Annamraju, S., et al., Early recognition of clozapine-induced myocarditis. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2007. 27(5): p. 479-83.

8.Murch, S., et al., Echocardiographic monitoring for clozapine cardiac toxicity: lessons from real-world experience. Australas Psychiatry, 2013. 21(3): p. 258-61.

9.Wooltorton, E., Antipsychotic clozapine (Clozaril): myocarditis and cardiovascular toxicity. CMAJ, 2002. 166(9): p. 1185-6.

10.Kar, N., S. Barreto, and R. Chandavarkar, Clozapine Monitoring in Clinical Practice: Beyond the Mandatory Requirement. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci, 2016. 14(4): p. 323-329.

11.Cohen, R., et al., A Case of Clozapine-Induced Myocarditis in a Young Patient with Bipolar Disorder. Case Rep Cardiol, 2015. 2015: p. 283156.

12.Merrill, D.B., G.W. Dec, and D.C. Goff, Adverse cardiac effects associated with clozapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2005. 25(1): p. 32-41.

13.Ronaldson, K.J., et al., Clinical course and analysis of ten fatal cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis and comparison with 66 surviving cases. Schizophrenia Research, 2011. 128(1-3): p. 161-165.

14.Haas, S.J., et al., Clozapine-Associated Myocarditis. Drug Safety, 2007. 30(1): p. 47-57.

15.Barry, A.R., J.D. Windram, and M.M. Graham, Clozapine-Associated Myocarditis: Case Report and Literature Review. Can J Hosp Pharm, 2015. 68(5): p. 427-9.

16.Ronaldson, K.J., P.B. Fitzgerald, and J.J. McNeil, Clozapine-induced myocarditis, a widely overlooked adverse reaction. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 2015. 132(4): p. 231-40.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal