An Elected House of Lords

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Law |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3721 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

The reform of the House of Lords has been a popular political and constitutional agenda for over a century. Lord Hailsham commented:

No one in his right mind could ever have invented the House of Lords with its archbishops and bishops, Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, hereditary peerages marshalled into hierarchical grades of dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons, its life peers nominated by the executive, its truncated powers, its absence of internal discipline and its liability to abolition.[1]

While successive governments declare many intentions to reform the House of Lords, little progress has been made to a move towards greater legitimacy and a result over the balance of power between the Houses. The most effective reform was the House of Lords Act 1999[2] which reduced the hereditary peers significantly had given the second chamber more confidence and a greater degree of legitimacy that must be acknowledged as an improvement in parliamentary power.[3] However, ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ strategy is not appropriate at the moment. But there has been no consensus on the method of reform (election, appointment or the mixture between two), leading to the failure of many proposals recently, the latest being the House of Lords Reform Bill, introduced to Parliament following the draft bill published in 2011[4] under the Coalition Government.

This essay will explore the recent reform, based on the 2012 Lords Reform Bill, regarding the election method. Central to this analysis is the belief that election provides democratic legitimacy, and thus legislative authority. This has direct implications for accountability and the balance of power within bicameral legislatures. This paper will consider the reform of the House and ask if such an institutional shift would lessen the democratic accountability of Parliament, undermine the composition and duties of the House, and challenge the legislative primacy of the House of Commons.

House of Lords Reform Bill (2012)

The Bill proposed several primary changes.[5] First, the second chamber would be comprised of a mainly elected second chamber (eighty percent) on the basis of proportional representation-PR and the remaining (twenty percent) appointed by an independent commission. Second, the size of the Lords should be deducted to 450 and the number of Lord Spiritual would be down to twelve.[6] Third, the Lords’ power and functions would not be changing with the maintenance of the primacy of the Commons.[7] Fourth, the connection between hereditary peers and the Lords would be tear apart, so that neither can create membership of the House on the other.[8] However, the bill had been withdrawn by Nick Clegg, the Deputy Prime Minister in September 2012 due to the breaking the coalition agreement from Conservative Party’s backbenches.[9]

An Elected House of Lords

As discussed above, the most significant primary issue with the Lords is the lacks of democratic legitimacy.[10] In order to solve this, the 2012 bill proposed an elected (or mainly elected) House. However, this would deteriorate the Lords’ democratic legitimacy and cause more problems (the loss of expertise and balance of Parliamentary Power). It is suggested that the election method would diminish the present positive aspects of the House.

(1) Democratic Legitimacy

Democratic legitimacy is often the key driver justification for implementing elections in the Lords. On June 21st, 2011, Lord Strathclyde introduced the Government’s proposals for House of Lords reform. In his opening remarks, he stated:

This House, although it has many party-political members, does not have democratic authority from the people it serves. Elections will establish a democratic legitimacy for work to be carried out […] the central principal of legitimacy through election should not be forsaken.[11]

Former Speaker of the House of Commons, now Baroness Boothroyd, responded to Lord Strathclyde’s belief that the Lords lacked democratic legitimacy, stating:

Our fatal flaw is that we are not directly accountable to the British people. That is absolutely true, but nor are the monarchy, the judiciary, the chiefs of the armed service, the Prime Minister, his deputy Mr. Clegg or – lets face it – the Cabinet directly accountable.[12]

Baroness Boothroyd argued that the Lords, like many other internal institutions within the British government, is not democratically legitimate individually. However, as a whole, the system still respects fundamental constitutional principles: solidifying the Parliament sovereignty and separation of powers.

The Lords may currently only suspend the passage of legislation first introduced in the Commons against the will of the lower chamber for up to one year (one month for bills regarding taxations and funding).[13] Also, any amendments approved by the Lords are ultimately accepted by the democratically elected House of Commons, thus making such legislation democratically legitimate. The sole exception to this constitutional agreement regards attempts by a Government to extend its own life; in this case, the Lords still holds veto power, a provisional check on the abuse of control within the Commons.[14] Some of the other defeats have also involved issues that could have an impact on civil liberties and democratic processes, including the Criminal Justice and Immigration Bill and the Counter-Terrorism Bill.[15]

It must be noted, however, that the Lords may still veto amendments proposed by the Commons if the legislation is first introduced in the Lords.[16] This provision allows for an undemocratically elected body to have final say over certain legislation – the sole instance in which the institutional structure of the UK legislature indeed lacks democratic legitimacy. However, in this situation, it remains important to differentiate between theory and practice. The overwhelming majority of legislation is first introduced in the Commons.[17] Additionally, after the enactment of the Parliament Act of 1911, its provisions were only implemented three times until the Parliament Act of 1949, which reduced the Lord’s right of bill suspension from two years to one. Since 1949, the act has only been used four times in Parliament.[18] Also, the Lords often try to compromise rather than “hold out in the face of determined opposition from the Commons.”[19] In other cases, the Lords has maintained their opposition on government bills and the government has ultimately ended this issue by dropping the contested part of its legislation.[20]

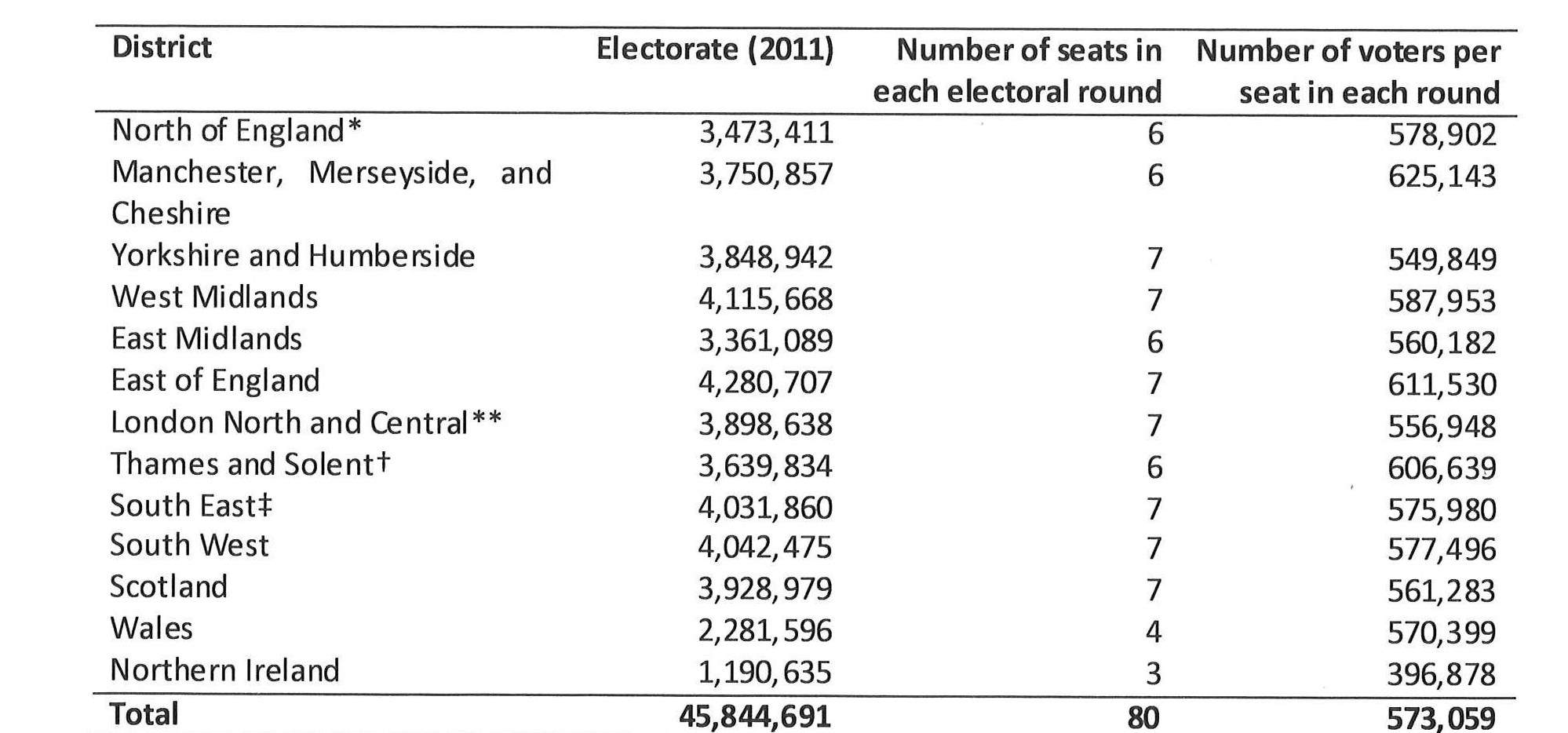

The White Paper Modernising Parliament: Reforming the House of Lords also emphasised that the introduction of an elected element into the reform which would become “more democratic and more representative second chamber.”[21] The composition of Lords should reflect different regions of the UK which are under-represented, including North West England, Yorkshire and the Humber, the East Midlands, and the North East. The PR method will divide the UK into thirteen electoral districts in terms of population and size, following Germany’s Bundesrat (The German Upper House).[22] Creating a territorial second chamber would give the UK a greater stake in the devolution settlement and prevent the country from tearing apart. However, the UK is not a federal state like Germany; instead an asymmetric, quasi-federal state after devolution, so regional peers hardly enjoy the electoral legitimacy. Additionally, the elected peers from devolved regions would initiate the debate on several contentious issues, regarding the devolution settlement. Scottish members, for instance, would scrutinise all government legislation, including its domestic affairs in order to protect its special interests and keep the distance from the central government. Bogdanor highlighted, “This would give them a wider remit than is to be enjoyed by non-Scottish MPs, who, following devolution, are no longer in practice in a position to scrutinise Scottish domestic legislation.”[23]

Democratic Accountability

Aside from the debate on legitimacy, proponents of an elected second chamber often overlook that Parliament enjoys an enormous amount of democratic accountability. The Westminster model guarantees this; the Prime Minister (PM) may be made accountable to Parliament at any time through a vote of no confidence, and the Government as a whole takes full responsibility for the creation and implementation of public legislation outlined in its manifesto.

In Parliament, such division of accountability is not usually considered a problem because power in Britain is highly centralised, and the executive is merged and directly accountable to the legislature. Accountability is centralised as well. The PM retains his or her position from the directly elected House of Commons, and if found unsatisfactory, may be replaced by a vote of no confidence via the Fixed Term Parliaments Act 2011.[24] Additionally, the PM is not directly elected by the voters, and cannot veto the decisions of Parliament based on the Salisbury Convention[25] and Parliamentary Acts[26]. Generally, when judging the quality of public legislation, there exists no confusion as to who is accountable – the Government in power.

This accountability, however, would be significantly threatened by an elected House of Lords. The second chamber gradually earned more power in legislative decision-making and the major institutional change could occur that led to a federal-style bicameral legislature in which the approval of both houses was needed for the passage of Acts, power, and accountability would be decentralised. If, in such a situation, the Government in power would hold a majority in the Commons but not in the Lords, failed public legislation could be blamed upon party politics and Parliament. This would lessen the responsibility of the PM and his cabinet, making government both less effective and less accountable. Power and responsibility in the Parliament are symmetrical; they rise and fall together. As a result, the introduction of an election would threaten Parliament’s high level of democratic accountability, thus making the creation and implementation of public legislation much more difficult.

(2) The Balance of Parliamentary Power

An adage regarding Lords reform states that by creating elections, one would ‘awake the sleeping Lords.’ The aphorism has negative connotations for the supposed lack of work in the second chamber, yet it also infers that by granting the Lords greater power via electoral legitimacy. In the circumstance that such dual democratic legitimacy developed in Parliament from the creation of an elected House of Lords, a constitutional crisis would ensue. Dual elections would represent an enormous challenge to the institutional design of the Parliament. Theoretically, in a legislature with an elected House of Lords, the primacy of the Commons, and in turn, the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 which reinforce such primacy, could be determined illegitimate. The House would no longer serve as a complementary body, but rather an equal body, to the Commons.

In a Parliament in which both Houses enjoy equal powers, the legislation would be subject to political strategy and stagnation. Exemplified by most recently the United States’ 2011 Congress crisis[27], disagreement between two equal houses can suspend the passage of critical public legislation. At present, the Westminster model nullifies such disagreement; the Commons retains primacy, and, crucially, mechanisms by which it may override the Lords’ power to suspend legislation.[28] This allows the House enough power to positively impact public policy and suspend controversial legislation, yet prevents the constitutional crisis of a doubly elected legislature. How Parliament would adjust to two elected, equally legitimate bodies is hypothetical and thus hard to predict. As democratic legitimacy is multiplied, authority is divided, and cooperation becomes increasingly difficult.

(3) The Level of Expertise

The primary purpose of the Lords is to scrutinise, critique and amend legislation. Thus, the effectiveness of the House is reliant upon the expertise of its members. Indeed, the greatest strength of the Lords is that it represents the most distinguished professionals in a wide variety of fields. Lord Chalfont remarked in 1977, “It is a rare experience to attend a debate in the House of Lords, on any subject from hare-coursing to nuclear strategy, in which there is not at least one participant who can legitimately be regarded as a leading authority on the subject.”[29] Such praise is not universal, however. As Baroness Murphy remarked, “Expertise has an expiration date.”[30] Measuring such expertise, however, is quite difficult as each member has differing interests and levels of involvement. Some continue to practise their profession part-time, while others are content to accept retirement and focus on their legislative duties. Nevertheless, this pool of expertise allows the Lords to undertake a better quality of scrutiny of legislation and executive action than its elected counterpart-the Commons. This is reflected in the highly regarded work of many of the Committees of the House of Lords: notably those concerning science, human rights, and constitutional matters; and the number of amendments tables in the Lords.[31]

European Union (EU) legislation, for example, is often highly technical, and advanced training in international law is often required to fully understand its provisions.[32] In this specific area, the Lords is particularly adept. The EU Committee is made up of a 19-strong Select Committee, appointed by the Lords and supported by six policy-specific sub-committees. Recently, the Committee has focused on scrutinising the Brexit process as well as holding regular meetings with UK Ministers and with political leaders from the EU-27.[33] It has recently published a report on the EU Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration on future UK-EU relations.[34]

Introducing elections to the Lords would, therefore, have both immediate and long-term negative consequences for the level of expertise within the House. In the short-term, because the overwhelming majority of current members are former or part-time professionals, with little to no political experience, many would choose not to retain their position through the election. This is compounded by the average of age of members being 69. Peers with distinguished careers and, in some cases health conditions, are unlikely to start making campaign signs and knocking on neighbourhood doors.[35]

Compounding this immediate loss in knowledge would be the long-term introduction of partisan nature and special interests. In fact, there is no overall majority of any political party, aided by the presence of 183 crossbenchers[36] with no political allegiance. The absence of elections, in the sense that members do not have to follow the party’s discipline and pressure to secure the seat. Since then members have more freedom to vote on their own personal views in comparison with the Commons. As a result, a Bill or amendment will be less likely blocked by one major section of the House.[37] Lord Strathclyde remarked in 1993 on the valued independence of the House, stating, “Members…speak for themselves entirely, not for lobbies, not for groups, not for interests, unions, they’re there on their own behalf.”[38] Additionally, special interests still exist in the Lords, but it is less dramatical than the Commons, particularly throughout the weekly PM’s Questions, where “MPs are often trying to make a good ‘sound bite’ for the next news bulletin, rather than take part in sensible, measured, and reasoned debate.”[39] The introduction of elections would exacerbate both issues.

Alternative Proposals

Any reform of the Lords needs to do several things: perceiving the issue of lacking democratic legitimacy; avoiding a replica of the Commons; and preserving the expertise of the House. It may also be considered that the inclusion of senior clergy of the Church of England, the continued presence of the hereditary Peers, and an unnecessarily large size that will continue to undermine the credibility of the House for many critics. There have been recent small-scale reforms concerning the resignation, expulsion, and exclusion of peers from the House via the 2014 and 2015 House of Lords Reform Acts.[40] Previously, peers could only leave the Lords through death or the voluntary retirement scheme as well as retain their title and position despite serious criminal offences.

Nevertheless, the principal and most commonly found proposals from those concerned with the reform all have flaws and do not meet these three requirements above. It may be necessary to re-consider a completely different reform for the upper House, particularly the Lord Bingham’s proposal of a ‘Council of the Realm’ could be seen as an acceptable and welcome one.[41]

What it has avoided, quite effectively, is abolition or unicameral like New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden. This has several causes. One of the most significant problems is the dominance of the governing party in the Commons that would impact on constitutional principles. In that sense, the Government is able to pass most of its proposals through the Commons by the whipped votes practice, with rare Government’s defeats.[42] The second issue is the Government’s control over the Parliamentary time. Also, the Government could not completely scrutinise all the works due to its complexity. Thus, if the UK adopted the unicameral model when abolishing the House of Lords, the Parliament would not be able to proceed with all the legislation and government action which could lead to a negative development.

Conclusion

The future of reform will most likely come as it has for over a century in the shape of small-scale changes meant to improve the workings of the current House. The election method has enjoyed mixed political motivation, and by all accounts little public interest. However, it has been seen that there are serious problems throughout the course of its debate and analysis with such a proposal. Regardless, the House of Lords will survive in some form. It has evolved as the concept of institutional design, and democracy has evolved; the chamber is a physical representation of re-invention, yet a continued tradition. In this sense, the Lords is the embodiment of English politics – deep respect for custom and convention, yet flexible enough for evolution and improvement. The Lords will continue to tread this awkward space between traditional concepts of bicameralism and the ever-changing definition of democracy, all the while enhancing the public legislation of Britain, and thus the state of Britain itself.

Appendixes

Appendix 1[43]

Bibliography

- 2010-2012 Parliamentary session, House of Lords Information Office, Work of the House of Lords 2010-12 (2013)

- Allan, P., The House of Lords (OUP 1988)

- Bingham, “The House of Lords: its future?” [2010] PL 261

- Bogdanor, Vernon, ‘Reform of the House of Lords: A Skeptical View’ [2003] 70(4) Rethinking Democracy 375-381

- Bogdanor, Vernon, The New British Constitution (4th edn Hart Publishing 2011)

- ‘Boundary Commission for England publishes final recommendations for new constituency boundaries’ (Boundary Commission for England, 31 March 2011)

- Boundary Commission for England, Newsletter Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland (Boundary Commission for England 2011)

- Bowers, Paul, ‘House of Lords Reform Bill 2012-2013: decision not to proceed’ (House of Commons Library, SN/PC/06405)

- ‘EU Select Committee: Scrutiny of Brexit-related treaties inquiry’ (UK Parliament, 21 January 2019) accessed 21 January 2019

- ‘European Union Committee – UK Parliament’ (UK Parliament, 3 July 2011) accessed 10 January 2019

- ‘Government defeats in the House of Lords’ (UCL Consitution Unit) accessed 20 January 2019

- House of Lords Debate, 21 June 2011

- Lord Hailsham, On the Constitution (Harper Collins 1992)

- Martin Elliot and Robert Thomas, Public Law (3rd edn OUP 2017)

- ‘Nick Clegg confirms Lords reforms have been officially withdrawn’ (BBC News, 3 September 2012) accessed 30 December 2018

- Parson, Michael, ‘Reform of the House of Lords: a “parliamentary version of Waiting for Godot’ (2009) 7(1) De la democratie au Royaume-Uni: perspectives contemporaines 1-20

- Russell, Meg, ‘Attempts to Change the British House of Lords into a Second Chamber of the Nation and Regions: Explaining a History of Failed Reforms’ (2018) 10(2) Perspectives on Federalism 268-299

- The report of the Joint Committee on Conventions (HL 265 HC 1212 2005-06)

- Wallace, Scott, ‘House of Lords Reform: Where Now?’ [2012-2013] 4(2) King’s College Law Review 74-81

- Watts, Duncan, The House of Lords: End, Mend or Defend? (Politics Association Resource Centre 1992)

Table of Legislation

- Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001

- Cabinet Office, ‘House of Lords Reform Draft Bill’ (Cm 8077, 2011)

- Counter-Terrorism Act 2008

- Fixed Term Parliaments Act 2011

- House of Lords Act 1999

- House of Lords Reform HC Bill (2012-2013)

- House of Lords Act 2014

- House of Lords (Expulsion and Suspension) Act 2015

- Parliament Act 1911

- Parliament Act 1949

- Salisbury Convention

[1] Lord Hailsham, On the Constitution (Harper Collins 1992), p. 48.

[2] House of Lords Act 1999, s 1 and s 2.

[3] Meg Russell, ‘Attempts to Change the British House of Lords into a Second Chamber of the Nation and Regions: Explaining a History of Failed Reforms’ (2018) 10(2) Perspectives on Federalism 268, p. 275.

[4] Cabinet Office, House of Lords Reform Draft Bill (Cm 8077, 2011)

[5] House of Lords Reform HC Bill (2012-2013) [52], sch 3

[6] House of Lords Reform HC Bill (2012-2013) [52], cl 1

[7] House of Lords Reform HC Bill (2012-2013) [52], cl 2

[8] House of Lords Reform HC Bill (2012-2013) [52], cl 1(4)

[9] See Bowers, House of Lords Reform Bill 2012-2013: decision not to proceed (House of Commons Library, SN/PC/06405); ‘Nick Clegg confirms Lords reforms have been officially withdrawn’ (BBC News, 3 September 2012) accessed 30 December 2018.

[10] But there needs clarifications between those two separated issues: legitimacy and and democracy. The Lords generally possess a degree of legitimacy, which means that it acts within the constitutional principles and proceed a great deal of valuable work. What the House does not possess is democratic legitimacy.

[11] House of Lords Debate, 21 June 2011, cl 155.

[12] House of Lords Debate, 21 June 2011, c1 172.

[13] Donald Shell, ‘The House of Lords and Constitutional Development’ in P. Allan (ed), The House of Lords (OUP 1988), p. 2.

[14] Shell, p. 190-207.

[15] Michael Parsons, ‘Reform of the House of Lords: a “parliamentary version of Waiting for Godot’ (2009) 7(1) De la democratie au Royaume-Uni: perspectives contemporaines 1, p. 14.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Duncan Watts, The House of Lords: End, Mend or Defend? (Politics Association Resource Centre 1992).

[18] Martin Elliot and Robert Thomas, Public Law (OUP 2017), p. 189-191.

[19] Parsons, p. 14-15.

[20] See further Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, s 23 and Counter-Terrorism Act 2008.

[21] House of Lords Reform HC Bill (2012-2013) [52], cl 1; Vernon Bogdanor, The New British Constitution (Hart Publishing 2011), c 6.

[22] See Appendix 1.

[23] Vernon Bogdanor, ‘Reform of the House of Lords: A Skeptical View’ [2003] 70(4) Rethinking Democracy 375, p. 379.

[24] Fixed Term Parliament Act 2011, s 2.

[25] See further the report of the Joint Committee on Conventions (HL 265 HC 1212 2005-06); Salisbury Convention.

[26] Parliament Act 1911, s 1 and s 2; Parliament Acts 1911-49, s 3.3.3.

[27] In 2011, the United States budget deficit approached the debt ceiling defined by US law. In the negotiations between Democratic President Barack Obama, and Republic Speaker of the House of Representatives John Boehner, party-politics and the approaching 2012 presidential election were often cited as an impediment to cooperation, and thus the passage of emergency legislation.

[28] Parliament Act 1911 and 1949.

[29] Shell, p. 66.

[30] Ibid.

[31] 2010-2012 Parliamentary session, House of Lords Information Office, Work of the House of Lords 2010-12 (2013) p. 2.

[32] ‘European Union Committee – UK Parliament’ (UK Parliament, 3 July 2011) accessed 10 January 2019.

[33] ‘EU Select Committee: Scrutiny of Brexit-related treaties inquiry’ (UK Parliament, 21 January 2019) accessed 21 January 2019.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Shell, p. 19

[36] 2010-2012 Parliamentary session, House of Lords Information Office, Work of the House of Lords 2010-12 (2013) p. 29.

[37] Scott Wallace, ‘House of Lords Reform: Where Now?’ [2012-2013] 4(2) King’s College Law Review 73, p. 74-76.

[38] Watts, p. 30.

[39] Wallace, p. 78.

[40] The House of Lords Act 2014 and 2015

[41] Bingham, “The House of Lords: its future?” [2010] PL 261

[42] There have been 48 government defeats in the House of Lords in the 2010-12 Parliamentary session; 27 in 2012-2013; 14 in 2013-2014; 10 in 2014-2015; 60 in 2015-2016; 38 in 2016-2017 ‘Government defeats in the House of Lords’ (UCL Consitution Unit) accessed 20 January 2019.

[43] Data originally taken from Boundary Commission for England, Boundary Commission for England publishes final recommendations for new constituency boundaries’ (Boundary Commission for England 31 March 2011)

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal