Hong Kong: Culture, Economy, History and Politics

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: International Studies |

| ✅ Wordcount: 6001 words | ✅ Published: 18 May 2020 |

Table of Contents

Introduction: Some Key Statistics

The Cultural Economy in Hong Kong

Historical & Political Insights

Knowledge Management & the HKSAR Economy

Hong Kong is not only a large city, but a sophisticated, multi-dimensional economy with globally spanning links. Therefore, when overviewing its current state and role within the global market, it is crucial to consider this from not only economic, but historical, industrial, social and cultural perspectives too. Only then can one establish understanding of a seemingly incongruous trading environment, and comprehend its ever evolving role on the world stage.

Introduction: Some Key Statistics

According to the World Population Review (2019), Hong Kong currently has a population of approximately 7.4 million. 92% of this is ethnic Chinese, with 2.5% Filipino and 2.1% Indonesian minority groups also present respectively (CIA World Factbook, 2019). The remaining 3.4% are primarily made up of western expatriates, in addition to other Asian minority groups, including those of Indians, Koreans and Japanese (See Appendix A for full statistics).

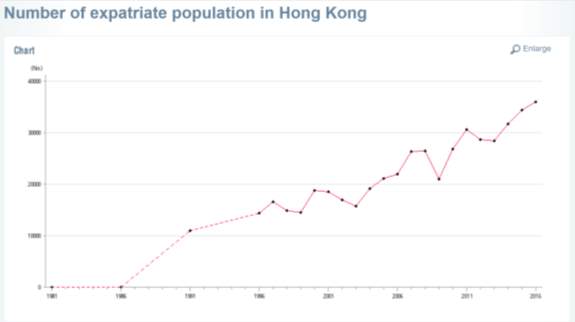

Given its colonial past under the UK, it may seem surprising that while 89% of the population is Cantonese speaking, only 4.3% are English speaking. However, while at one point a trade hub within the British Empire with more migrants than locals by the mid 20th century (Ching, 1974), Chinese immigrants later flooded the city, in escape from poor living conditions in the mainland (World Population Review, 2019). As such, the current expatriate population stands at roughly 36,000, comprising 0.49% of domestic inhabitants (see Appendix B for exact figures).

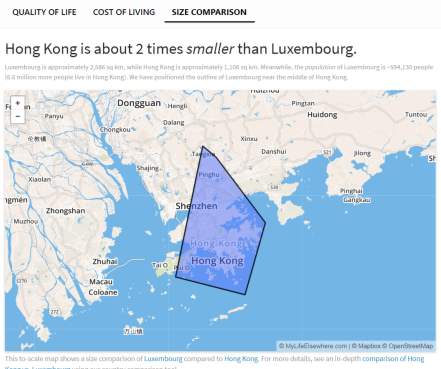

With a land area (~1073 sq. Km) less than half (MyLifeElsewhere, 2019) that of Luxembourg (2586 sq. Km), Hong Kong has little in the way of naturally occurring resources. In fact, Law (2014) reports that the city relies on the mainland for over half of its electricity supply, 70% of its water, and over 90% of meat & vegetable consumption.

Heaver (2017) reports that local mineral deposits fed an industry that thrived for a time. While the CIA factbook confirms that this is still in existence, its output is comparatively negligible to other key sectors.

How then, has the city achieved an annual GDP of $341.1bn (CIA, 2019), comparable to South Africa? The main natural advantage of concern is the city’s defining feature: its possession of an excellent natural harbour point. This gave the city a distinct advantage as a British trading post, and facilitated the commerce of goods from both sides of the world.

This feature permeates Hong Kong’s status as a nexus of trade to date, driven by an economy ranking 32nd worldwide based on IMF estimates (Statistics Times, 2018, see Appendix C). Indeed, the city currently stands as a global hub – whether it be for trade, finance, or logistics – of business activity, a miracle of paradox. While originally a British colony, the city-state now exists as a Special Administrative Region (SAR) under the People’s Republic of China, under the “one country two systems” model. This model was developed to ensure that Hong Kong retained its liberal policies and various freedoms for at least 50 years after the British handover in 1997.

The Cultural Economy in Hong Kong

Given its uniquely bridging position between the powers of East and West, one would think the cultural make-up of Hong Kong would be marred by the natural dichotomy at play. This could not be further from the truth. Some, including Kit-wai Ma (2005) muse that while “Hong-Kongers” are ethnically Chinese like their mainland counterparts, their capitalistic roots crucially raised them above their comparatively “primitive” communist counterparts. Carroll mentions that as early as the 1800s, Chinese residents began to self-distinguish themselves from those living in the mainland due to marked differences in social and economic structures. As Kit-wei Ma and indeed many researchers affirm, the moulding of this impression was aided in no small part by local television, which attained specific worldwide acclaim of its own.

With origins in the early 20th century, Hong Kong-based productions saw a surge in popularity in South-East Asia during the 1950s, with Mandarin productions also catering to the mainland market (Chu, 2009). As one of the largest of its kind in the world, the Hong Kong film industry accounts for 13% of mainland Chinese revenue, China currently holding the position as the world’s largest market for televised entertainment (HKDC, 2019).

Kong (2006) notes that the city, lacking natural resources, has gravitated more towards a “cultural economy” as she terms it. The film industry lies at the crux of that for Hong Kong. Given its nature, social networks play a key role in its continued development and evolution. As such, despite government schemes drafted in support of the industry, retaining competitiveness has been difficult in the face of the rapid expansion of regional counterparts such as the Bollywood industry in India. Some even attribute the industry’s demise to the loss of the culture from the colonial “golden age” of the city.

Interestingly, if we examine Hofstede’s analysis of the “Hong-Konger” culture (carried out using his famously cited six dimensions of culture), we can observe marked differentials between that of the city-state, its mainland counterpart, and especially their previous colonisers. This supports the notion of a distinctly localised culture being developed over time, and visualises a fascinating convergence of Eastern and Western cultural values into something entirely divergent itself.

Broadly touching upon Hong Kong’s scores, we can see a gravitation towards collectivism, in line with their Mainland counterparts. Taken in conjunction with their distaste for over-indulgence (final score) and a general acceptance of social inequality (first score), we can see the remnants of Chinese influence from pre-colonisation. Interestingly though, with the other three criteria – those being masculinity vs feminism, uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation – we witness a sometimes stark alignment with British values relative to those of their geographic neighbours. In light of the sheer geographic separation between Hong Kong and thee UK, as well as the somewhat temporary nature of the city-state’s colonisation in a grand timeline, we can view British cultural influence as a surprisingly strong factor in the shaping of local identity in the city.

Historical & Political Insights

The founding of Hong Kong seems rather accidental when reviewing British historical accounts. Indeed, Tsang (2004) notes that the initial adoption of colonial rule over the Hong Kong territories occurred as a side effect of the conclusive treaty to the first opium war in 1841. He asserts that “The main British concern was to secure the right to trade in China and make as much profit as possible”. It is clear that Hong Kong was a trading post first and foremost, a settlement second.

Duara (2017) notes that Hong Kong initially featured a trade-focused economy, having, as Carroll (2007) points, one of the best natural harbours in the world. This eventually evolved into an industrial hotspot, and later the financial hub we recognise at present, supported by efficient British administration and vital positioning within the Chinese silk-road. This final development, as she notes, occurred as a result of a unique monetary policy, which struck a tailor-made compromise between the colonial system of the British government and that of a Dollar-dominated global market. By granting local tradesmen the benefit of the Sterling Area while exempting certain stakeholder groups, notably those involved in the banking sector, from the constrictions of colonial policy. This is said to have attracted swathes of capital to the city-state from investors looking to exploit any resultant currency arbitrage opportunities (between the floating and fixed sterling rates).

When examining the financial system more closely, its Anglo-Saxon origins become more apparent. In fact, Carroll observes that much of Hong Kong’s initial trade and financial facilities were imported directly from other British colonies, especially during the 19th century. This applied to governance too, which itself was the product of lessons in administration learned from other colonies like India, Singapore and New Zealand. As such, officials at all levels of the hierarchy were themselves distinct from the overwhelmingly native Chinese population, which created an impasse between Hong Kong and its colonisers.

Overviewing these roots helps explain detachment between British and Chinese layers of colonial Hong Kong’s society. But why then, do locals today display such confident favour towards British rule?

Besides the liberties afforded to Western-style societies, a degree of cultural “symbiosis” played a significant role too. Wing Sang Law (2009) recounts that in the lead up to the Chinese revolution, the colonial administration took proactive steps to promote Chinese traditionalism within Hong Kong at a time when revolutionaries were on the rise in the mainland. This was reportedly done with the intention of addressing concerns regarding the potential spread of Chinese communism into the territory. In fact, after 1926, Hong Kong governor Cecil Clementi is said to have opened dialogue with Qing dynasty courtiers with the intention of preserving conservative Chinese culture in the colony. As a fluent Cantonese speaker and man of scholarly interest in Chinese history, Cecil embodied the unique colonial culture that became an offshoot of this venture.

The colony had for decades been painted in nationalist Chinese imagery as a “lost-soul”. Wing Sang Law reports that following the Sino-Japanese war of the 1930s, Chinese intellectuals streamed into the city-state, bringing with them strong elements of modernism and elitism into the fabric of Hong Kong society. British conservatism in combination with Chinese traditionalism ultimately served to preserve the city’s distinct culture.

Most threatening to the status-quo was the 1997 handover. Fong & Lui (2017) speculate that the executive authority post-handover failed to unite the diverse elements of the city’s governance structure – elites, institutions, public representatives and the like – in the same manner done by a socially conscious colonial administration. One attribute that did survive past colonial rule, was the unilateral authority of the chief executive as the head of government. The reasoning behind this preservation? Simply put: elitism, and Beijing’s vested interest in it. To iterate, Fong & Lui mention specific concerns raised by Chinese officials in the lead-up to the handover regarding the governance system China would inherit. Increasing diversity within the legislating body, while seemingly democratic, in reality allows for a stronger pro-Beijing front to dominate at the expense of several minority pro-democracy factions. These institutional changes were “engineered” by the Chinese as early as the 1980s, almost 20 years before sovereignty transferred.

Fong & Lui continue to make interesting points about the rather unique structural makeup of the city’s administrative system, and the political environment this creates. They cite the top-levels of this hierarchy as key differentiating factors with regard to the ability of constituents to make political power-plays, stating that with the “presidential” system commonly adopted by Western democracies, loyalties tend to lie with the general public, to whom the elected president is accountable. The key difference in Hong Kong lies in the absence of publicly elected officials at the top-level. Fundamentally, this means that pro-government officials ultimately look to fulfil their obligations to Beijing, not those of the governed public. This crisis of loyalty has only manifested itself deeper into the hierarchy, as the political noose is gradually tightened around populist platforms and independent parties operating within the legislature headed at present by Chief Executive Carrie Lam, who herself has never faced elections.

Economic Highlights

Shifting to a macro-based perspective, it becomes clear that Hong Kong’s economy currently stands at a point of distinctive polarity. Tied by sovereignty to China, but intrinsically tied to the US simultaneously through the pegging of the Hong Kong Dollar to the US Dollar, Coface (2019) comments that Hong Kong’s economy both benefits and suffers from a unique cyclical mismatch between those of the superpowers.

The slowing growth of China, which itself pegs the renminbi to the USD, threatens the local economy, which is prone to the shockwaves caused by the recent trade war between the country and the US. In fact, exports equate to 190% of GDP, of which more than half are “re-exports” to the mainland. This high dependence on external influences is dangerous, and places the $341bn economy in a precarious position, despite a healthy budget surplus of HK$149bn (Lam, 2019) and contingency capital. Increasing links to the mainland such as those already cemented between the stock exchanges of Hong Kong, Shanghai and Shenzhen, also expose the city to global market fluctuations.

In fact, in its most recent economic report (Q1) for the HKSAR Panel on Financial Affairs (2019), a marked decline in export activity was primarily attributed to a drop in global economic activity. As an open, “externally-oriented” economy, Hong Kong is vulnerable to increasingly volatile global markets, an issue which supports claims that economic downturn has cyclical tendencies, justifiable by its capitalistic roots and status as a premier IPO destination. After all, one can only sensibly assume that a global business hub may feature economic elements influenced (in part) by the business cycle.

With further reference to its mainland-based overseer, the city forms a crucial part of extensive planning on Beijing’s part around the Greater Bay Area (GBA) integration project. To iterate, this describes a long-term plan to integrate Hong Kong, Macau and the greater Guangdong province into one synergised economic area. It should be noted that upon completion of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau bridge, visitation rates to the city saw a 10% leap. This project forms partial foundation for the eventual realisation of the GBA initiative, and brings the city one step closer to greater integration with the behemoth mainland economy. The political aftermath of this however, rests as another matter entirely.

The Economist’s Intelligence Unit reports that the Chinese-lead initiative is expected to be complete by 2035, and will focus on leveraging economic strengths specific to each city/region within the area, Hong Kong’s strong financial services sector and judicial system being a prominent example of these. While practical in theory, the qualitative implications of this project may be difficult to project, especially those concerning the delicate political situation existent between Hong Kong and China, as the Unit reports. With regard to this, various incentives aimed at Hong Kong residents also risk the ire of comparatively disadvantaged mainland cities.

As an externally oriented economy, it comes as no surprise that trade statistics feature prominently in government economic reports. Indeed, according to the HKSAR Trade & Industry Department (2019), Hong Kong currently features the world’s 7th largest trade economy, alone constituting 3.2% of global trade flows, ahead of nations such as the UK, Italy and Canada.

Knowledge Management & the HKSAR Economy

Another concept of relevance to macro-development is that of knowledge management. With the term “knowledge management” defined as “the systematic management of information and learning” (APM, 2019), knowledge-based economies operate on the basis of efficiently allocating economic resources on the basis of effective information utilisation. Zhu & Chou (2018) report that concentrated ownership structures in the city drive larger, dominant organisations upwards at the detriment of small medium enterprises (SMEs). Following the city’s transition from manufacturing hub to tertiary sector powerhouse, labour pools promptly concentrated on organisations centred likewise. The extent of this resulted in a massive 84.6% of employable workers falling under the umbrella of large service-sector organisations. This ultimately harms entrepreneurial interests in the region, constricting knowledge-flows to the filters of conglomerates in the region. By encouraging self-influenced social mobility, the researchers suggest that knowledge-flow, and as such innovation beyond core industries, can be encouraged in the city. This may even provide potential solutions to the ailing film industry.

Fan et al (2019) shed light on the social value FDI can have to developing knowledge-flows. Citing studies on other highly internationalised economies including Australia and Canada, they point out that spikes in local competition triggered by multinational entries, encourage “knowledge diffusion” into the domestic market. Through created “linkages” and networks, such conglomerates can act as channels of knowledge exchange between the domestic economy and the wider world. They argue that presence of quality human capital helps to reduce communication and cultural barriers which may hinder knowledge absorption. One could argue that Hong Kong benefits from this more than its mainland counterpart, due to the presence of greater social freedoms and English-speaking ability.

Their data certainly supports such comments, with the coloniser-colony relationship found to facilitate even greater language transfer than shared borders and FDI alone (see Appendix D for data). The same can be said of economic data. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) World Investment Report (2019) highlights Hong Kong as the world’s 3rd largest recipient of FDI, as well as the 4th largest centre for FDI outflows (exact figures can be seen in Appendix E).

However grand in stature these results paint the city, Zhu & Chou’s research implies that much of the capital being invested or generated here is still concentrated heavily in commercial trade-based industries. With government investments in innovative enterprise lagging significantly behind those of their Asian counterparts, coupled with decreasing funds for education, facilitation of knowledge-generation remains a key economic issue to the city, still ripe with potential for growth in this area given its rich cultural heritage.

Strikingly, Zhu & Chou cite Human Capital Theory as a basis of justification for the economic significance of education. Given Hong Kong’s long past move from manufacturing to service sectors, worker skillsets must be upgraded accordingly to encourage continuation of knowledge-economies. As they argue, “overeducation” leads to natural economic adjustments to reclaim the inherent equilibrium between education and productivity.

Indeed, Findlay et al (1996) affirm that moves by Hong Kong-based manufacturers to exploit cheaper mainland labour in the late 20th century allowed local labour to gravitate towards more modern, skill-based industries, namely semiconductors. As a result, the IMD World Talent Ranking 2017 places Hong Kong 1st in Asia for enticing quality labour (FSDC, 2018).

Could this position be leaning on highly-skilled expatriates though? When researching distributions of expatriate workers across key local sectors, they found expertise and competence to be the main reasons cited for hiring these migrants over local talent. With Hong Kong-based companies known among the most active in the mergers & acquisitions industry (FSDC, 2018), it is possible that the above result could be influenced heavily by inorganic labour growth. This may help shed light on the domestic education issue, as the global destination may be relying on increasing migratory flows over domestic talent.

Could this also explain the elitism still prevalent in the city? Lo’s (2016) comments on increasingly pay-based educational programming certainly support this possibility. When moving towards this new status-quo from a previously equalitarian system, the effects on opportunities for social mobility are sure to be adverse.

While increased entrepreneurial incentive could offset such change, this, as mentioned, also seems to be on the decline. By neglecting SME activity, less opportunities are created for labour pools to diversify, leading Findlay et al to claim that this has a devaluation effect on domestic human capital. While positive drivers, such as a 200% tax cut to R&D expenditures (FSDC, 2018) do exist, diminishing social freedoms and democratic strength under Chinese authority post-handover can only serve to further such concerning trends.

Trade & Financial Sectors

Overholt (nd) casts attention to the dire effects the handover had on the city economy. First and foremost were the concerns about freedoms afforded under Chinese rule, leading to mass emigrations in the 1990s, totalling as high as 66,000 in 1992 (AFP, 2017). Moreover, In the midst of the 1998 financial crisis in Asia, Japanese banks initiated mass withdrawals of overseas funds. This action hit Hong Kong especially hard. As Overholt reports, withdrawals from the city totalled a sum equivalent to 150% of GDP at the time. The handover in conjunction with these events placed Hong Kong, in light of global perception, as a dying paradise of old.

With this in mind, the city’s recovery in the following decade should strike one as nothing short of incredible. Overholt argues that this can be attributed to the fact that libertarian rights were preserved, and investors quickly re-assured that no Chinese crackdown on asset holdings would occur immediately post-handover.

While this clearly did not occur, struggles stemming from systematic disparities between the city and the mainland continue to exist. Primary among them is the Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect, which allows traders on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange to directly purchase Chinese assets and securities trading on its Shanghai-based counterpart.

The system was drafted with the initial purpose of taking advantage of Hong Kong’s sophisticated trading system, as opposed to the rudimentary equivalent across the border. However, in line with China’s breakneck development, its system has fallen closer in line with the global marketplace, its derivatives offerings following suit, yielding Shanghai increasing power over a previously dominant Hong Kong. Recent disagreements over the banning of dual-class shares in China (John & Kwok, 2018) and the competition disequilibrium this move potentially creates within the Stock Connect have only highlighted this trend, and serve as an alarming reminder to Hong Kong institutionalists that their influence could be waning.

Before moving forward it is important to take a closer look at the development of the Hong Kong market itself. Its founding the result of a merger between the all-Chinese Hong Kong Sharebrokers’ Association and the (non-Chinese) Hong Kong Stock Exchange after the Second World War. While other exchanges did open in the decades following, Pauluzzo & Geretto (2013) report that they were again unified under the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong by 1980. After 1989 the Hong Kong Clearing Company was established as a central clearing house for securities trading.

By the turn of the millennium, moves were made to merge these entities into one unified organisation, the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX), which in turn came to be the largest RMB clearing centre internationally (FSDC, 2018). It was from the 2003 Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Agreement that the roots of the links between the HKEX, Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges stem.

Such links solidified the global standing of the HKEX. The exchange now acts as an intermediary for over 90% of mainland China’s global trade (FSDC, 2018). This in no small part aids Hong Kong’s status as the 6th largest exporter and 7th largest importer in commerce value globally. The GBA project and other Chinese trade integration projects also serve greater demand for domestic (and Chinese) securities.

Such broad trade is well serviced by a strong judicial system. This was ranked 16th globally on the Rule of Law Index, above other financial centres such as the US. Strong legal protections for intellectual property lend assurance to international investors anxious about prevalent copyright infringements across the continent.

With fiscal policy renowned for its business-friendliness, corporations establishing operations also enjoy a wide assortment of tax incentives, including a favourable corporate tax of 16.5%, extremely low income tax levels, an absence of capital-gains tax, and lax distinction rules between tax-liable organisations.

Looking at trading volume statistics surrounding the Asia Pacific region (available in Appendix F), the Hong Kong market accounts for approximately 16% of trading activity in the region (Focus,2019). The city also holds responsibility for the management of $135bn worth of private-equity in Asia, or around 15% of its aggregate asset pool. While this may be due in part to PE fund-targeted tax exemptions, the city’s position as the prime wealth management hub for an increasingly affluent China lends its industry substantial credibility.

Given the city’s status as a world financial centre, it would be prudent to dig deeper into this industry when exploring the city’s economic strength. Lee et al’s (2014) paper on “financialisation”, defined as the relative increase in influence of banking and financial sectors on both domestic and international economies, raises interesting points about how Hong Kong’s financial infrastructure not only strengthens its own economy, but acts as a pillar for the global one.

Under this proposed model, economic growth is spurred by not only productivity, but rather the appreciation in value of assets, current and non-current. This however, as they argue, creates a system promoting investor value over those of the common (non-investor) citizenry. This especially applies to corporations, which as such would further use shareholder value as a measure for growth success. Could this reflect a decline in consumerism in Hong Kong?

Research by Cheung et al (2007), stating that the Hong Kong Stock Exchange features many attributes mirroring those of Western (or developed) counterparts, seems to support this. While this would yield clear advantage to institutional investors, who would be able to cross-list with relative ease, one should note the tendency of Anglo-Saxon market participants to prioritise shareholder interest over that of consumers. It is true though, that alignment with global markets opens up opportunities for new market entrants, and as such expanded consumer choice.

Further claims are made, that Hong Kong based companies also exhibit characteristics similar to those in developing Asian nations. The contradictions continue with research by Claessans & Fan (2002) indicating that, while the benefits of concentrated ownership structures (common in Asia) generally favour less developed nations, this structure is common among enterprises in Hong-Kong, itself among Asia’s most developed economies. Given that entrenched shareholders have greater voting power over organisational decision-making, these findings would also support Lee et al’s arguments.

Have small (retail) investors lost market freedoms then? Despite the ominous findings detailed, this does not seem to be the case as of yet.

In fact, the Hong Kong Futures Exchange introduced the Hang Seng Mini Index shortly after the handover (HKEX, 2019). This entails futures and options contracts based on the renowned Hang Seng Index, but with lower multipliers and margin requirements. These are purposed towards retail investors with lower capital requirements, and help maintain open access to the market for general consumers.

As the leading world centre for Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), new entrants are also constantly flooding the market, in turn influencing a gargantuan market capitalisation value totalling 1277% of GDP, the largest of its kind in the world. This prompts continuous evolution in the marketplace, with vast opportunity entailed for institutional and retail investors alike.

Future Outlook?

Keeping the discussed economic variables in mind, Manzini (2013) claims that the dual nature of Hong Kong as a cultural and economic centre provides its greatest potential for future growth. Taken in tandem with its well-reputed distribution networks, he theorises that this allows for efficient “migration” of innovations based in the city to either China or the wider global community.

Economic realisations of this concept indeed already exist, the Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect and film industry being prime examples among them. This serves to prove that Manzini’s ideas of a culturally harmonious state capitalising on its primary synergies have evidential grounding.

To conclude, Hong Kong presents a multi-dimensional picture of not only its British colonisers and Asian neighbours, but the wider world too. As a melting pot of global culture and economic interrelation, the city’s present state is as vibrant, if not more so, than its past. While political uniformity remains a challenge, as Chinese enterprises begin to seek the global market, and international institutionalists the once barred promise in the mainland, Hong Kong still finds itself perfectly placed, and adapted, to facilitate commercial interests on both sides.

References

- Central Intelligence Agency (2019). The World Factbook. East Asia/Southeast Asia: Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/hk.html [Accessed on 02/03/2019]

- Social Indicators of Hong Kong (2019). Number of Expatriate Population in Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.socialindicators.org.hk/en/indicators/internationalization/22.10 [Accessed on 02/03/2019]

- Violet Law (2014). Hong Kong’s Inconvenient Truth. Foreign Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/08/21/hong-kongs-inconvenient-truth/ [Accessed on 02/03/2019]

- MyLifeElsewhere (2019). Country Size Comparison. Available at: https://www.mylifeelsewhere.com/country-size-comparison/hong-kong/luxembourg [Accessed on 02/03/2019]

- HKTDC Research (2019). Film Entertainment Industry in Hong Kong. Available at: http://hong-kong-economy-research.hktdc.com/business-news/article/Hong-Kong-Industry-Profiles/Film-Entertainment-Industry-in-Hong-Kong/hkip/en/1/1X000000/1X0018PN.htm [Accessed on 02/03/2019]

- Karen Chu (2009). 100 Years of Hong Kong Cinema. The Hollywood Reporter: Business. Available at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/100-years-hong-kong-cinema-81158 [Accessed on 12/03/2019]

- Lily Kong (2006). The Sociality of Cultural Industries: Hong Kong’s Cultural Policy and Film Industry. Pp. 61-76. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10286630500067812?needAccess=true [Accessed on 12/03/2019]

- Hofstede Insights (2019). Country Comparison. Available at: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/china,hong-kong,the-uk/ [Accessed on 14/03/2019]

- Prasenjit Duara (2017). Chapter 8: Hong Kong as a Global Frontier. Hong Kong in the Cold War, Chapter 8. By Priscilla Roberts, John M. Carroll. Pp.211-220. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UsM9DgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA211&dq=hong+kong+economy+&ots=YRG79UpboW&sig=sNv0SG8jkpj8YeNDALTZz7RRSww#v=onepage&q=hong%20kong%20economy&f=false [Accessed on 14/03/2019]

- John M. Carroll (2007). A Concise History of Hong Kong. Pp. 1-68, Chapter 1&2. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=fQofAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP3&dq=hong+kong+economy+history&ots=uOJgDmSW7Y&sig=xYSNT-h0vqha5eFXnjU_vkkbsGY#v=onepage&q=hong%20kong%20economy%20history&f=false [Accessed on 14/03/2019]

- Steve Tsang (2004). A Modern History of Hong Kong: 1841-1997. Pp. 1-29, Chapter 1&2. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=PeeKDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=founding+of+hong+kong&ots=c-0Xo4KIS4&sig=9WYtqE1xpRZPQyM2nm4sKHIVsPw#v=onepage&q=founding%20of%20hong%20kong&f=false [Accessed on 14/03/2019]

- Wing Sang Law (2009). Collaborative Colonial Power: The Making of the Hong Kong Chinese. Pp.100-130. Available at: https://hongkong.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.5790/hongkong/9789622099296.001.0001/upso-9789622099296-chapter-6 [Accessed on 14/032019]

- Brian C.H. Fong, Tai-Lok Lui (2018). Hong Kong 20 Years After the Handover: Emerging Social and Institutional Fractures After 1997. Studies in the Political Economy of Public Policy. Available at: https://link-springer-com.proxy.lib.strath.ac.uk/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-51373-7.pdf [Accessed on 15/03/2019]

- Coface for Trade (2019). Economic Studies: Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.coface.com/Economic-Studies-and-Country-Risks/Hong-Kong [Accessed on 14/03/2019]

- Hong Kong SAR Government (2019). Meeting of LegCo Panel on Financial Affairs. Available at: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr18-19/chinese/panels/fa/papers/fa20190603cb1-1138-1-ec.pdf [Accessed on 13/04/2019]

- The Economist, Intelligence Unit (2019). The Greater Bay Area: the shape of things to come? Available at: http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=187744002&Country=Hong%20Kong&topic=Economy [Accessed on 12/04/2019]

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Trade and Industry Department (2019). Trade Statistics. Available at: https://www.tid.gov.hk/english/aboutus/publications/tradestat/wmttt.html [Accessed on 12/04/2019]

- Alex Yue Feng Zhu, Kee Lee Chou (2017). Hong Kong’s Transition Toward a Knowledge Economy: Analyzing Effect of Overeducation on Wages Between 1991 and 2011. Available at: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs13132-018-0535-z.pdf [Accessed on 20/04/2019]

- Association for Project Management (2019). Context: Governance: Knowledge Management. Available at: https://www.apm.org.uk/body-of-knowledge/context/governance/knowledge-management/ [Accessed on 20/04/2019]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2019). World Investment Report 2019: Special Economic Zones. Pp. 1-7.Available at: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2019_en.pdf [Accessed on 04/05/2019]

- M. Findlay, F. L. N. Li, A. J. Jowett and R. Skeldon (1996). Skilled International Migration and the Global City: A Study of Expatriates in Hong Kong. Pp. 49-61. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/622923?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed on 04/05/2019]

- Alex Lo (2016). Only in Hong Kong: Elitism Spreads to Kindergartens. CNBC, Life. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/01/only-in-hong-kong-elitism-spreads-to-kindergartens.html [Accessed on 04/05/2019]

- William H. Overholt (nd). A Decade Later: Hong Kong’s Economy Since 1997. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/hkjournal/PDF/2007_fall/4.pdf [Accessed on 03/05/2019]

- Rubens Pauluzzo, Geretto Enrico (2013). Stock Exchange Markets in Hong Kong: Structure and Main Problems. Transition Studies Review 20.Pp. 1-15. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257677833_Stock_Exchange_Markets_in_Hong_Kong_Structure_and_Main_Problems [Accessed on 03/05/2019]

- Focus (2019). Market Statistics – June 2019. Domestic Capitalisation. Available at: https://focus.world-exchanges.org/issue/june-2019/market-statistics [Accessed on 02/05/2019]

- Kim Ming Lee, Benny Ho Pong To, Kar Ming Yu (2014). Financialisation and Economic Inequality in Hong Kong: The Cost of the Finance-led Growth Regime. Chapter 6. Pp. 127-146. Available at: https://link-springer-com.proxy.lib.strath.ac.uk/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-51373-7_6.pdf [Accessed on 02/05/2019]

- HKEX (2019). Mini-Hang Seng Index Futures. HKEX, Equity Index, Hang Seng Index (HSI). Available at: https://www.hkex.com.hk/Products/Listed-Derivatives/Equity-Index/Hang-Seng-Index-(HSI)/Mini-Hang-Seng-Index-Futures?sc_lang=en#&product=MHI [Accessed on 05/05/2019]

- Yan-Leung Cheung, J. Thomas Connelly, Piman Limpaphayom, Lynda Zhou (2007). Do Investors Really Value Corporate Governance? Evidence from the Hong Kong Market. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, Volume 18, Issue 2. PAGES NEEDED. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-646X.2007.01009.x [Accessed on 13/05/2019]

- Ezio Manzini (2013). Hong Kong as “Laboratory of the Future”. Pp. 59-70. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1511965?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed on 20/05/2019]

- Stijin Claessens, Joseph P. H. Fan (2002). Corporate Governance in Asia: A Survey. International Review of Finance, 3:2, 2002: pp. 71-103. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1468-2443.00034 [Accessed on 21/05/2019]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2019). General Profile: China, Hong Kong SAR. Available at: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/countryprofile/generalprofile/en-gb/344/index.html [Accessed on 22/05/2019]

- Statistics Times (2018). Projected GDP Ranking (2019-2023). Available at: http://statisticstimes.com/economy/projected-world-gdp-ranking.php [Accessed on 03/06/2019]

- Stuart Heaver (2017). Inside Hong Kong’s Abandoned Mines. Post Magazine, South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2077433/inside-hong-kongs-abandoned-mines [Accessed on 04/06/2019]

- Fan Shuh Ching (1974). The Population of Hong Kong. Department of Statistics, University of Hong Kong. The Committee for International Coordination of National Research in Demography. Pp. 1-49. Available at: http://www.cicred.org/Eng/Publications/pdf/c-c21.pdf [Accessed on 20/05/2019]

- AFP (2017). HK20: Looking Back – The Hongkongers Who Emigrated Before the Handover. HKFP, Community & Education, Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.hongkongfp.com/2017/06/24/hk20-looking-back-hongkongers-emigrated-handover/ [Accessed on 22/05/2019]

- World Population Review (2019). Hong Kong Population 2019. Available at: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/hong-kong-population/ [Accessed on 02/06/2019]

- Eric Kit-wai Ma (1999). Culture, Politics and Television in Hong Kong. Chapter 1-8. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203978313 [Accessed on 05/06/2019]

- Zhaobin Fan, Hui Li, Lin Pan (2019). FDI and International Knowledge Diffusion: An Examination of the Evolution of Comparative Advantage. MDPI, Sustainability. Pp.1-17. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/3/581/pdf [Accessed on 10/06/2019]

- Eric Lam (2019). Hong Kong’s Budget Surplus Shrinks as the List of Headwinds Grows. Bloomberg, Markets. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-25/hong-kong-s-budget-surplus-shrinks-as-list-of-headwinds-grows [Accessed on 10/06/2019]

- Hong Kong Financial Services Development Council (2018). Overview of Hong Kong Financial Services Industry. FSDC, May 2018. Available at: https://www.fsdc.org.hk/sites/default/files/Overview%20of%20HK%20Financial%20Services%20Industry_E.pdf [Accessed on 12/06/2019]

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2019). The Four Key Industries and Other Selected Industries. Available at: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp80.jsp?productCode=FA100099 [Accessed on 13/06/2019]

- Alun John, Donny Kwok (2018). Hong Kong’s Bourse Brushes Off Chinese Snub Over Dual-Class Shares. Reuters, Business News. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-stocks/hong-kongs-bourse-brushes-off-chinese-snub-over-dual-class-shares-idUSKBN1K60WV [Accessed on 14/06/2019]

Appendices

Appendix A

| Demographic (Hong Kong) | Statistic (2018) | |

| Population | Rank 104 (World Population Review) | 7,213,338 |

| GDP | $341.4bn (as of 2017) | |

| Ethnic Groups | Chinese (92%), Filipino (2.5%), Indonesian (2.1%), Other (3.4%) | |

| Languages | Cantonese (88.9%), English (4.3%), Mandarin (1.9%), Other (1.9%) | |

| Proportion of population aged 25-54 | 43.96%

(Median age = 44.8 years) |

|

| Life Expectancy | 83.1 years | |

| Growth Rate (population) | 0.29% | |

| Land Area: | ||

| Land Mass | 1073 sq. Km | |

| Water | 35 sq. Km | |

| Total Land Area | 1,108 sq. Km |

(Figure 1: CIA World Factbook – Hong Kong) – Quoted Statistics)

Appendix B

(Figure 2: Expatriate Population in Hong Kong, 1991-2016. Social Indicators of Hong Kong)

NOTE: The above data has been collected from the Hong Kong Immigration Department from 1991 onwards. Therefore, no pre-1991 data is displayed.

Appendix C

Appendix C

(Figure 3: GDP (Nominal) Ranking 2019 – International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook (October 2018) ).

NOTE: As nominal estimates, the data shown above does not represent actual economic output from the given period, but rather forecasts made by the IMF

Appendix D

(Figure 4: Fan et al (2019): Data and Descriptive Statistics. The General Effect of FDI on the Pattern of Competitive Advantage).

The coefficients given above denote correlations between chosen characteristics affecting the capacity of analysed economies to facilitate “knowledge diffusion”.

Appendix E

(Figure 5: UNCTAD, General Profile: China, Hong Kong SAR )

Appendix F

(Figure 6: Global Exchanges by Trading Volume – Asia Pacific Region. Focus, Market Statistics – June 2019.)

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal