The EU’s Emission Trading System (EU ETS)

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Environmental Studies |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3537 words | ✅ Published: 18 May 2020 |

The EU’s Emission Trading System (EU ETS)

Introduction

To introduce this topic we first need to know what EU ETS (European Union Emission Trading Scheme) consists on and which is it’s origin.

- What is EU ETS?

EU ETS is a keystone of the EU’s policy to mitigate climate change and lead to the depletion of the greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively.

It consists on a cap, which is the maximum amount of emissions that a company can produce. Thus, there is a limit that can’t be exceeded. Furthermore, this cap is reduced overtime so that emissions are lowered.

One of the keys of this policy are the trading emission allowances that may be traded among companies, so that if a company emits less than the cap it is able to sell the excess carbon permit to other company that pollute more. As there is a limit on the total number of allowances, they have a value which benefits less polluting companies and could be an incentive to reduce emissions.

If a company can’t cover its emissions with allowances a heavy fine will be imposed. On the other side if a corporation hasn’t covered all its emission allowances it can keep the remaining ones for the future or sell them to other firms that need them.

- Origin of EU ETS

To find the roots of the EU ETS we have to look at the Kyoto protocol (signed in 1997) which is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This commits its Parties, which are 38 countries called “Annex-B-countries”, by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets. This countries were essentially industrialised and in transition countries.

The targets of this protocol were settled to be applied to the period 2008-2012 when this countries were to reduce the emission discharge of greenhouse gases with 5.2% below 1990 levels and, according to Sonja butzengeiger and Axel Michaelowa (Volume 39, 2004, Number 3) in order to reduce compliance costs “flexible mechanisms” were defined – emissions trading at the country level and the project- based mechanisms Joint Implementation (JI) and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

On the one hand CDM projects were executed by non participating developing countries in the emissions trading scheme, on the other hand, JI projects were carried out in industrialised countries. Both mechanisms were a cost effective way to achieve the targets of the protocol.

European policy makers, after the Kyoto agreement was reached, were more aware about the emissions trading matter.

The European Commission published a Green Book on CO2 emissions trading in march 2000 due to the increase of CO2 emissions in the EU at the end of the 1990s. After that, a multi-stakeholder working group in the European Climate Change Programme was created. This group agreed to introduce trading permits in green house gas emissions (GHG) in Europe as soon as possible. Thereafter, in October 2001 the European Commission approved a directive based on European trading GHG permits which was published in July 2003 (it became a law in October later that year).

Furthermore, the emissions trading scheme that was developed covered more than 10.000 installations in 25 member states.

Theory of marketable pollution permits

In order to understand how the allowance permit system works we have to go back to 1968 when J.H.Dales introduced the idea of pollution permits.

This idea emerges when the authority allows only a level of certain pollutant emissions and so, issues permits for this quantity. This permits can be bought and sold in the market which makes them tradeable.

Before going on, we have to highlight some essential concepts such as what the Marginal Abatement Cost curve (MAC) and Marginal External Cost (MEC) are (chapters 4 and 6, Pearce and Turner):

“The MEC is the value of the extra damage done by pollution arising from the activity measured by Q“. When MEC and MNPB (Marginal Net Private Benefit) intersect we identify the optimal level of pollution.

When introducing taxes to the system, this charges in pollution try to encourage the installation of pollution abatement equipment among emitters. The polluter adjusts this pollution charge by altering the level of activity giving rise to the pollution.

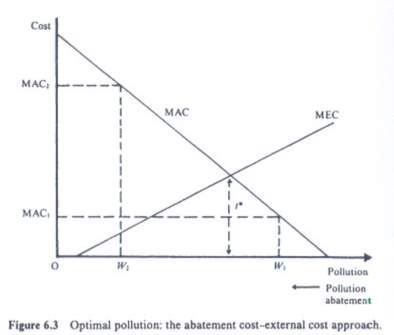

In this figure (Pearce and Turner chapter 6) it is shown the MAC and MEC curve. If we are in W1 level of pollution the marginal cost of reducing it is MAC1, the same happens with W2 (But in this case the Marginal cost is MAC2). This shows that at first, it is easier to clean up initial levels of pollution, but as there is less pollution left is much more expensive to reduce it.

MAC equals MNPB curve if only we can abate pollution by reducing output.

Now that we now these essential concepts we can continue with the explanation of tradeable permits. To do so, we will explain it using figure 8.1 (Pearce and Turner chapter 8).

We need one permit for each unit of emission of pollution. 0Q* is the optimal number of permits at the optimal price of 0P*. S* is the supply curve of permits (“Their issue is regulated and is assumed not to be responsive to price” (Pearce and Turner, 1990)). If the authorities want to achieve Pareto optimum, they should issue 0Q* permits.

We can associate the MAC curve with the demand curve for permits. Thus, if the price for permits is P1 the polluter will buy 0Q1 permits. So that, if the level of pollution is Q2 the polluter will abate pollution which is cheaper than to buy permits. But to the left of Q1 is cheaper to buy permits.

Permits must be tradeable for six reasons that we will briefly explain:

- Cost minimisation

Polluters that have low cost of abatement will need to buy less permits than others that have high costs of abatement. As there are different costs of abatement there will be a market where low-cost polluters sell their permits to high-cost polluters. This means that the total cost of abatement is minimised (compared to the regulatory approach of setting standards) and shows the cost-effectiveness of permits.

- New entrants

If new polluters enter the market, the permits demand curve will shift to the right. If authorities want to maintain the same number of permits (same supply S*), the price of them will increase to P** as shown in figure 8.3 (Pearce and Turner chapter 8). This will mean that if new polluters are high-cost abatement industries they will have to buy this permits. The overall cost minimisation properties of the permit system is maintained.

However, the authorities could increase the supply of permits if they wanted (to avoid relaxation in the level of pollution control) by issuing new permits (S* shifts to the right) or if they want to tight the system they could enter the market themselves and buy permits (S* shifts to the left).

- Opportunities for non polluters

The permits market is free so that if an environmental pressure group wants to lower pollution, they can enter the market and buy permits holding them out of the market or destroying them. If the government disagree with the level of pollution that is imposed they can simply issue new permits.

- Inflation and adjustment costs

Permits adjust to inflation as they respond to supply and demand. Furthermore with permits we just define a standard and find a way to issue this permits which is more efficient than using taxes.

- The spatial dimension

When establishing taxes we have to consider the different assimilative capacities of pollution of the different reception points (points where pollution is received). There are also synergistic effects which mean that aggregate damages are larger than single damages. Permits avoid this problem.

- Technological “lock in”

Permits are issued in a quantity equal to the standard required so that if abatement cost are underestimated the price of this permits will go up. If abatement costs are underestimated when using taxes, polluters will pay the tax (that is set lower than it should be) and won’t invest in abatement equipment. Permits have advantages over charges in this sense.

Benefits of EU ETS

EU ETS has been a successful implementation in a diverse range of contexts, both political, economical and social. Nevertheless, we will later see all the drawbacks this c

We will outline some of the benefits that this scheme has according to the international carbon action partnership (2016).

To do so, we will group this benefits into three categories: Environmental effectiveness, economic sense and further public policy objectives.

- Environmental effectiveness

ETS targets emissions:

As we mentioned in the beginning, establishing a cap that limits the amount of GHG emissions allows the system to ensure that those emissions are below a specific limit marked. This enables emission reduction targets to be met with high degree of certainty.

ETS enables clear emissions reduction paths

The objective of the scheme is the depletion of the GHG emissions. To achieve this, the cap that is established is not static but dynamic, so that is a progressively declining cap which enables a credible long term policy signal and emissions trajectory aligned with mid-to long-term targets.

In addition having a clear and defined emissions depletion pathway set provides predictability for economic actors, as it shows market expectations and gives us a clear signal for necessary long term investments.

- Economic sense

ETS delivers cost-effective abatement

Allowances can be bought and sold after the first distribution, that’s because a resale market creates the possibility of cost-effective reduction and puts a price on the emission allowances.

Companies that have cheaper abatement options can sell their allowances which can be purchased by companies with more expensive abatement possibilities. This leads to an efficient allocation of abatement efforts among firms.

ETS provides flexibility

This means that the participants can invest in the abatement when and where they want .

Temporal flexibility for example, allows participants invest whenever they decide so that firms can take benefit from innovations and invest at a time that is cheaper for them. This means that participants will invest when its more cost effective for them.

Another important fact is that, as mentioned in the international carbon action partnership (2016): “External crediting systems that generate ‘offsets’, such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), provide additional flexibility relating to where abatement takes place. Offsets allow certified emissions reductions to be made outside the scope of the ETS, expanding the range of abatement options available and driving down the cost of compliance. However, as the unrestricted use of offsets can pose a risk to the integrity of the ETS, limits on the quality and quantity of offsets are usually put in place.”

ETS encourages low carbon developement, decoupling emissions from economic growth

We tend to link carbon emissions with energy generation, so that if emissions are reduced this will have a negative impact in te economy growth, but this is not necessarily true. There are lots of developed and industrialised countries that are heading to decarbonisation and at the same time are improving the carbon intensity of their economies. This is mainly because the energy efficiency and productivity of these economies has grown overtime.

As an example, even though California’s carbon intensity has fallen 33% since 2001, its state’s economy has grown by 37%.

ETS promotes the deployment and innovation of low-carbon technology

Low carbon power comes from technologies that enable us produce power with substantially less amount of carbon dioxide emissions than is emitted from conventional fossil fuel power generation.

As ETS establishes a carbon price, market conditions change favoring low carbon production processes which are an incentive for firms and entrepreneurs to perform innovation activities and invest in the mentioned processes.

- Further public policy objectives

ETS generates revenues

ETS generates fiscal revenue by auctionuing allowances.

The uses that the regulator can give to this revenues are vast, but there are three that stand out among the rest: earmarking, tax reform and protecting low-income households.

- Earmarking: the government can allocate the revenues in many specific uses that can contribute to lower the costs of decarbonisation. Furthermore, this earnings can be invested in research and implementation of more effective low carbon technologies.

- Tax reform: the revenues earned can be reinvested by the government and reduce other taxes such as labour or capital ones. Thus, it will make the tax system more efficient. This is just an approach because it hasn’t been implemented yet anywhere.

- Low income household protection: Revenues can be used to compensate the poorest households for the increasing carbon costs (as they are the least equipped to adjust to them).

ETS produces emissions data and facilitates information sharing

Companies report information about the emissions that generate which is helpful to know whether the system is functioning well and tracking the progress in order to achieve mitigation targets.

ETS creates substantial co-benefits

Although the main objective is the depletion of the GHG emissions it can create other positive outcomes such as public health (if GHG emissions are reduced there will be less polluted air which is beneficial in the long run), energy security, job creation and land-use change.

ETS can be adapted to country-specific contexts

This means that EU ETS can be adjusted to fit national and sub national priorities and objectives. In addition, EU ETS as a supra-national system covers facilities in 31 different countries with economic profiles that differ.

ETS is politically feasible

This program is compatible with current policy frameworks and is politically acceptable. Furthermore, the scheme works well obtaining consensus among domestic interest groups and will also help by addressing concerns of particular stakeholder groups.

ETS allows for linking with other systems, fostering international climate action

Different systems can be associated with the mutual recognition of emission allowances which creates a larger and more efficient carbon market.

Drawbacks and critics to the EU ETS scheme

Although we have seen the benefits of this program there are also plenty of critics because of the results that have happened since the introduction of this policy:

- The ETS has not substantially reduced emissions

Since this program is active EU’s greenhouse emissions have fallen, but there’s no evidence that this reduction is due to the scheme. In fact, studies show that the reduction of this emissions in ETS sectors can be explained by a combination of increases in renewable energy, economic downturn post-2008, fuel switching from coal to gas and energy efficiency improvement.

- The EU ETS is used to undermine other climate emissions control policies

There was a modification in the EU’s integrated Pollution Prevention and control (IPPC) directive to exclude CO2 emissions as well as a revision to weaken the energy taxation directive so that carbon prices weren’t affected by these.

This shows that they worried more about the market rather than the efficiency of the energy or the well-being of the population.

- The ETS sets a ceiling on climate ambition

ETS ensures these targets of emissions are considered a ceiling not a floor so there is no incentive for countries to reduce more their emissions because that would encourage other companies to emit more. To date, the net result has been “cancelling out the abatement that is being delivered by other policies such as the Renewable Energy Supply Directive and the Energy Efficiency Directive.” (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2015).

- The EU ETS has not been cost-effective and has subsided polluters at tax payers’ expense

In this system carbon costs have been passed on to consumers by businesses and a lot of firms have gained billions of euros of unearned profits. The sector that has benefited the most is the power sector, one example that we can consider is a study from Uwe Leprich (Saarbrucken University, Germany) which shows that the introduction of CO2 costs was fully included in electricity prices even though energy companies received the majority of their credits for free.

The most affected are poorest households as a higher proportion of their income is spent on energy.

- The ETS remains susceptible to fraud and gaming

According to the Corporate Europe Observatory “The legal definition of emission allowances is not sufficiently clear, the Registry of allowances lacks adequate fiduciary controls, and there is poor cooperation between the Commission and national financial regulators”.

Conclusion

To end with, I’ll give a conclusion about this matter. There are arguments for and against this scheme.

EU ETS creates an open carbon dioxide market and gives incentives to companies in order to reduce their emissions. These incentives are essential for achieving the objective of the depletion of greenhouse gas emissions. In my opinion, in order to accomplish this objectives and have the benefits mentioned above, a structural change should be made to the EU ETS policy.

Furthermore, the policy was adopted by all 27 EU states which at least shows that they are all aware of this global problem (even if the program fails).

Despite all the benefits that we described before, we later saw all the critics this policy has due to all the bad results that the program carried in reality.

This policy not only did not make businesses reduce their emissions but allowed them to make extra profits by passing on the costs to the consumers. Other negative aspects from this policy include: over-allocation of permits, windfall profits, offsetting, price volatility and a failure in achieving their goals.

As stated by Friends of the Earth Europe “This is at a time when the EU urgently requires large infrastructure investments, such as modernised electricity grids[1], up-front financing for energy efficiency and greatly accelerated renewable energy development.”

Appendix

List of references

- Alexander Eden, Charlotte Unger, William Acworth, Kristian Wilkening, Constanze Haug (2016) “Benefits of Emissions Trading, taking Stock of the Impacts of Emissions Trading Systems Worldwide” International carbon action partnership

- Online at: https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/?option=com_attach&task=download&id=575

- Bagchi Chandreyee and Eike Velten (2014): The EU Emissions Trading System: Regulating the Environment in the EU.

- Online at: https://climatepolicyinfohub.eu/eu-emissions-trading-system-introduction

- Capros P, Manzos L (2000). The economic effects of EU-wide industry level emission trading to reduce greenhouse gases. Institute of Communications and Computer Systems of National Technical University of Athens

- Online at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/enveco/climate_change/pdf/primes.pdf

- Corporate Europe Obsevatory (2015). EU emissions trading: 5 reasons to scrap the ETS.

- Online at: https://corporateeurope.org/en/environment/2015/10/eu-emissions-trading-5-reasons-scrap-ets

- Davide timmons (2019). How to have an all-renewable electric grid. Online at: https://www.siliconrepublic.com/machines/all-renewable-electric-grid-possible

- Delbeke J (2006). Preface. In: Delbeke J (ed). The EU Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme, EU energy law vol IV. Claeys and Casteels, Leuven

- Online at: http://claeys-casteels.com/documents/toc/EEL4.pdf

- European Commission (2005) EU Action against climate change: EU emissions trading—an open scheme promoting global innovation. Brussels

- Online at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdfs/2007/pub-2007-015-en.pdf

- European Commission (2006) “The EU emission trading scheme”. Luxembourg

- European Comission . EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

- Online at: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets_en

- Friends to the earth (2010). The EU Emissions Trading System: failing to deliver.

- Online at: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/docs/0005/registered/9825553393-31_friends_of_the_earth_europe_en.pdf

- Helena Hansson (2010 ). Is emissions trading a solution to climate change? – A study with the focus on the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme. Lund university

- Online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3005/cb5e9492b6b6b821e8b6dd72648adec75ef8.pdf

- International carbon action partnership (2015) “7 Arguments for Emissions Trading”

- Online at: https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/?option=com_attach&task=download&id=378

- Pearce, D. & Turner, R.K. (1990). Economics of natural resources and the environment, Chapters 4, 6, 8.

- Skjaerseth JB, Wettestad J (2008). “Making the EU Emissions Trading System: The European Commission as an entrepreneurial epistemic leader” Global Environmental Change, Vol 20, No 2, 2010, pp. 314-321. Fridtjof Nansen Institute, P.O.Box 326, N-1326 Lysaker, Norway.

- Online at:

- http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.737.3953&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Sonja Butzengeiger, Axel Michaelowa, Claudia Kemfert, Jochen Diekmann, Hans-Joachim Ziesing, Joachim Schleich, Regina Betz, Werner Betzenbichler, Katja Barzantny, Michael Klein, Martin Kruska, Michael Hahn, Jens-Peter Wegner (Volume 39, 2004, Number 3, page 116 to 131). The EU Emissions Trading Scheme – Issues and Challenges.

- Online at: https://archive.intereconomics.eu/downloads/getfile.php?id=345

- Tamra Gilbertson (2009). Carbon trading how it works and why it fails. Online at: http://www.carbontradewatch.org/downloads/publications/mercado_de_emisiones.pdf

- United Nations Climate Change. What is the Kyoto Protocol?

- Online at: https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol

- Yanna G. Franco, (2003) El comercio de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero de la Unión Europea: “ Efectos sobre el crecimiento económico y la calidad ambiental”. Complutense University of Madrid. Law Faculty.

[1] As stated by David Timmons (2019 ) “Because solar and wind conditions vary across the landscape, system costs fall as a production area grows, so there needs to be a robust electric grid to move electricity from places where there is supply to places of demand”.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal