Social Justice Education: Centering Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy in Teacher Education

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Education |

| ✅ Wordcount: 2740 words | ✅ Published: 03 Nov 2020 |

Abstract

Currently, children from various ethnic backgrounds and cultures are attending schools in the United States. However, newly graduated teachers are not prepared to teach children with different cultural backgrounds of their own, leading to deficit perspectives towards students of color (Hill, 2009). Teachers entering their careers with this limiting perspective can embody implicit biases throughout their teaching, which has a detrimental impact on students of color and their quality of education. This perspective can also reinforce inequities and sustain privilege within groups of students (Ladson-Billings, 1995). That being said, a teacher’s pre-service education is crucial in creating teacher mindsets that embrace a culturally sustaining pedagogy. This research intends to explore how current pedagogies and curriculum for pre-service teachers can be improved to inform teachers towards a social justice mindset.

Throughout this research, it is explored how teacher education programs are formed in relation to academic content and pedagogy. Analysis from researchers indicate that a social justice pedagogy must be integrated throughout a teacher education program to provide accountability for teachers in creating a culturally sustaining mindset. This can be supported through meaningful field experiences, provided if mentor teachers are adept at explaining concepts and scaffolding teachers to success. Pre-service teachers also need a space to critically reflect on their self-identity in relation to its influence on students. The implications of this research indicate that these facets of social justice education will create teachers that are more prepared to help students of color succeed in schools.

Teacher Curriculum and Pedagogy

Teacher education programs have certainly evolved over last few decades. Although more universities are implementing social justice education into their teacher education programs, more empirical research is needed to explore its effectiveness (Mills & Ballantyne, 2016). Lee Shulman (1986) and his work pertaining to Pedagogical Content Knowledge is used frequently in teacher education programs to balance academic content and pedagogy instruction. Shulman himself questions “how can a successful college student transform expertise in subject matter in a for students can understand?” (p. 8) This is an even more loaded question when placed in terms of cultural relevance (Ladson-Billings, 1995). For teachers that are not well-versed in cultural responsiveness, students that come from various cultural backgrounds unfortunately are thought of as students who have deficits that must be fixed. Teachers are expected to learn about multicultural education however, the integration of multicultural education within teacher education programs varies across the United States (McDonald, Bowman, & Brayko, 2013). Despite this, there needs to be more than one course about multicultural education, as one course does not provide an adequate amount of time for one to develop an in-depth understanding of culturally responsive teaching (Bennett, 2012).

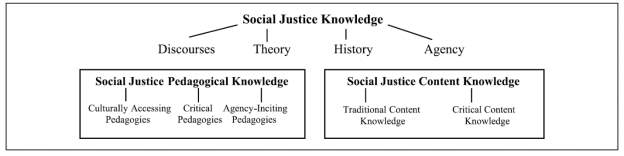

Researchers are now looking at past frameworks of teacher curriculum and pedagogy, while reframing it to suit the increasing need to develop teachers’ understanding of equity and social justice. For example, Dyches and Boyd (2017) used Shulman’s initial sources of teacher knowledge and created the framework called Social Justice Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (SJPACK). This framework consists of three domains: Social Justice Knowledge, Social Justice Pedagogical Knowledge, and Social Justice Content Knowledge. The first domain, Social Justice Knowledge, reiterates the importance of the teacher’s knowledge of systems of oppression, privilege, and domination, knowing that these issues are exacerbated by everyday actions for students of color. The second domain, Social Justice Pedagogical Knowledge (SJPK), is how a teacher makes decisions from classroom management to learning strategies to maximize student learning in ways that have students thinking critically not only about the academic content but how students can apply their activism outside the classroom. Culturally accessing pedagogies is a crucial part of SJPK in that teachers must be intentional about how they respect and integrate students’ cultures, utilizing students’ funds of knowledge in the curriculum. The third domain, Social Justice Content Knowledge, is the teacher’s understanding of how traditional forms of content, standards, and language project a sense of power and privilege. The culturally responsive teacher will still present traditional content but in a way that responds to students’ emotional needs and motivations.

Figure 1. SJPACK (Dyches and Boyd, 2017)

Although SJPACK has not yet been fully integrated into teacher education programs, it is a fresh, new take on what could be in the near future. It is also an excellent starting point for current teachers who need a social justice framework to utilize when planning curriculum. The website Teaching Tolerance (2016) has also provided a list of Social Justice Standards for primary grades up through twelfth grade for teachers to use and reframe their lessons in terms of identity, diversity, justice, and action. Another framework that has been rethought in recent years is Ladson-Billings’ Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (1995). Ladson-Billings warns of the danger of cultural mismatch, stating that schools and their power structures have the potential to reproduce social inequalities. She states that culturally relevant teachers must have high expectations for all students, demonstrate a connectedness with all students, and that teachers be flexible and fluid with the formation of knowledge. Her work has also been connected to its implications in incorporating multiliteracies in the classroom. Smolin and Lawless (2010) assert that a culturally relevant approach should also include students’ digital identities and experiences to build upon their unique funds of knowledge.

Although Ladson-Billing’s piece was a landmark in framing social justice education, Paris and Alim (2014) stated it is overdue for an updated perspective. For example, even the term “relevance” does not carry enough prominence in its goals to support students of color. Paris and Alim (2014) offer the concept of culturally sustaining pedagogy, to focus on sustaining the outcomes of the challenges to social justice education. In doing so, we must distance ourselves from deficit approaches that aim to have marginalized communities become like the dominant group, which causes them to lose their heritage and cultural traits to gain a quality education. Paris and Alim (2014) also state that teachers must sustain cultural traditions, as well as adapt to the fluidity and ever-changing ideals of the culture of young people within communities. A culturally sustaining pedagogy must be incorporated through each course taught in a teacher education program, in order for teachers to question their own roles in maintaining a cultural pluralistic society that values students’ funds of knowledge and moving away from a monolingual and monocultural environment (Paris, 2012).

Impact of Field Experiences

Teachers need to be taught to care for students and form meaningful relationships with them. Teachers also need to learn how to appreciate and see the wealth in students’ funds of knowledge and use that to frame the curriculum (McDonald et al., 2013). Gonzalez, Wyman, and O’Connor (2011) assert that “learning about students and their communities is as important as learning about subject matter and content” (p. 482). In order to do so, pre-service teachers need to “see” students, which is key to building relationships with children and their families, fundamental to teaching from a social justice perspective, and central to high quality teaching. Doing so allows teachers to make concrete notions of students and communities that may seem abstract from coursework. For teachers to gain a sense of the diversity that exists in schools, meaningful field experiences can be a valuable part of a teacher education program. (Mcdonald et al., 2013).

Through multiple studies, pre-service teachers have shown a developed sense of cultural awareness by participating in a field experience during their program. McDonald et. al (2013) had participants at University of Washington interact with children and families at Community-Based Organizations (CBOs). Not only did participants get to have one-on-one interactions with children and staff, but they also got to see the workload students took home with them and how their schooling impacted children outside of school. It was clear that interacting with children had a profound impact on some candidates, but the study highlighted how important it is certain factors play into a candidate’s experience.

One aspect that was instrumental to a candidate’s experience were the directors and mentors involved in the CBOs. One candidate, Claire, was able to deepen her knowledge about the students and families involved in her CBO, due to program’s director providing Claire with background information about specific families, preventing Claire from forming assumptions. Another candidate from the study, Margo, was guided by her mentor teacher, Jessica, and invited to participate in practices at the CBO and was explained why certain aspects of their routine were important in building a community. Margo seized these opportunities to learn and was given feedback and support, which was notably absent from another candidate’s experience. Dallas was another closely followed candidate in the study who although was placed in a similarly structured CBO, did not experience the same deep understanding of community as Margo. Dallas’ mentor, Rosaline, was not as adept of conveying her knowledge to candidates, which restricted Dallas’ learning opportunities, affecting his ability to reflect upon his practice during school assignments.

Bennett (2012), another researcher focused on field experiences, was able to offer a similar example of how one-on-one interactions are a fundamental part of a field experience. Each of the participants had little knowledge of culturally responsive teaching before starting their field experience. All of the participants developed a greater understanding of culturally responsive pedagogy after their experience was over. However one group of participants demonstrated deeper knowledge and were more self-aware. Part of the reason why Group A was able to develop deeper knowledge and self-awareness was because the participants had more one-on-one interactions with students than Group B, being able to form personal relationships with specific students and reflect on the impact of those relationships.

On the other hand, Vass (2017) studied the impact of detrimental mentor relationships in Australia. Vass explained that in Australia participants thought of communities they worked in as very segregated. Participants were faced with multiple barriers in their field experiences, one of which being that their mentor teachers had established deficit perspectives of students. One mentor teacher introduced a student to a participant as “low-ability.” Another participant, Alice, found that her mentor teacher undermined her efforts to see the wealth of her students’ cultural knowledge and instead enforced assimilation into a White dominant curriculum. Participants also mentioned the barriers within the strict curriculum, despite the ever-growing diverse populations in Australia. Vass stated the power struggle between participants and mentor teachers and explained participants had a lot to lose by speaking up against their mentor teachers, doing so creating barriers to their success in completing the program.

Either way, there is not always a set standard for how field experiences are implemented and how mentor teachers are vetted. It implies that there needs to be specific training for mentor teachers to employ specific social justice standards and know how to navigate situations in which participants experience cognitive dissonance, when their prior knowledge does not match their new knowledge. This is crucial to helping teachers challenge their prior beliefs in order to form new understandings of diversity and think more positively about their students’ cultures and beliefs (Bennett, 2012).

Critical Reflection

According to Dyches and Boyd (2017), “Reflection, then, is a key component of agency because it requires teachers to channel their social awareness to catalyze change for their students.” In other words, the ability for teachers to self-reflect is a crucial part in developing a social justice mindset. Being able to do so helps teachers identify implicit bias, which can greatly affect their view of students and contribute to deficit perspectives towards groups of students. Howard (2003) explores the components of critical reflection and emphasizes its importance in teacher education programs. He states that teachers must be prepared to participate in discomfort and look deep within themselves before attempting to see their students. According to Palmer (1998), “we teach who we are” and without knowing our own perspectives and de-centring our points of views, we will contribute to the underachievement of groups of students.

Howard (2003) explains that teacher educators must provide spaces for pre-service teachers to explore their prejudice and uncertainty and be able to facilitate conversations about race and culture. Howard even created a course titled “Identity and Teaching,” focusing on pre-service teachers’ self-identity in relation to race, social class, and gender. Instructors of the course had to undergo a three-day workshop to be prepared to discuss these complex topics.

Hammond (2014) also identified three tasks every teacher must work through to uncover implicit bias and prepare to work with diverse students: a) identify your cultural frame of reference, b) widen your cultural aperture, and c) identify your key triggers. By identifying your own cultural frame of reference, you are accepting your own cultural identity and being aware of the space you take up through that identity. Widening your cultural aperture allows you ask questions about your culture and examine your deep cultural values and how they intersect with what influences your teaching. Identifying your key triggers allows the teacher to manage their own emotions, which influences’ students’ mood and productivity. All of this is crucial to teachers’ continual self-reflection and needs to be implemented in teacher education programs. Using Howard and Hammond’s work, if all teacher education programs had a course or incorporated topics from this course, pre-service teachers would have multiple opportunities to participate in critical reflection and be able to apply this during their field experiences and coursework.

Conclusion

Although there has been research about culturally sustaining pedagogy and adopting a social justice perspective for pre-service teachers, these frameworks have yet to be implemented nationwide, nor are they a requirement for all teachers. However, with our diverse populations of students and fluidity of cultural customs among young people, it is necessary for teachers to be educated in these frameworks. Pre-service teachers must also interact with diverse children and families through field experiences, be mentored by capable educators that are adept at explaining cultural customs and their importance, as well as p be provided with spaces to self-reflect about their own cultural identities.

It is implied from this research that not only could pre-service teachers greatly benefit from this work, but educators could also benefit from trainings about culturally sustaining pedagogy, incorporating funds of knowledge, as well as participating in critical self-reflection. With the continued research in regards to social justice and teacher education, it is hopeful that more universities will adopt a social justice approach and embed it throughout their programs. Pre-service teachers will greatly benefit from developing a deep understanding of culture, equity, and power structures and applying their knowledge to helping their students of color, who are the furthest from educational justice.

References

- Bennett, S. V. (2012). Effective Facets of a Field Experience That Contributed to Eight Preservice Teachers’ Developing Understandings About Culturally Responsive Teaching. Urban Education, 48(3), 380–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085912452155

- Dara Hill, K. (2008). A Historical Analysis of Desegregation and Racism in a Racially Polarized Region. Urban Education, 44(1), 106–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085907311841

- Dyches, J., & Boyd, A. (2017). Foregrounding Equity in Teacher Education: Toward a Model of Social Justice Pedagogical and Content Knowledge. Journal of Teacher Education, xd68(5), 476–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117705097

- Gonzalez, N., Wyman, L., & O’Connor, B. H. (2011). The Past, Present, and Future of “Funds of Knowledge.” In B. A. U. Levinson & M. Pollock (Eds.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Education (pp. 481–494). Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Howard, T. C. (2003). Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Ingredients for Critical Teacher Reflection. Theory Into Practice, 42(3), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1353/tip.2003.0031

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163320

- Mcdonald, M. A., Bowman, M., & Brayko, K. (2013). Learning to See Students: Opportunities to Develop Relational Practices of Teaching through Community-Based Placements in Teacher Education. Teachers College Record, 115(4). Retrieved from https://www.tcrecord.org

- Mills, C., & Ballantyne, J. (2016). Social Justice and Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(4), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116660152

- Palmer, P. J. (1998). The Courage to Teach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Paris, D. (2012). Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189×12441244

- Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2014). What Are We Seeking to Sustain Through Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy? A Loving Critique Forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.982l873k2ht16m77

- Smolin, L. I., & Lawless, K. (2009). Using Multiliteracies to Facilitate Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in the Classroom. In D. R. Cole & D. L. Pullen (Eds.), Multiliteracies in Motion (1st ed., pp. 173–187). New York: Routledge.

- Teaching Tolerance. (2016). Social Justice Standards. Retrieved December 9, 2019, from https://www.tolerance.org/frameworks/social-justice-standards

- Vass, G. (2017). Preparing for Culturally Responsive Schooling: Initial Teacher Educators into the Fray. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(5), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117702578

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal