How Physical Education Contributes to Pupil Development

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Education |

| ✅ Wordcount: 4172 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Explain how your subject contributes to the spiritual, intellectual, moral, social and cultural development of pupils.

I paraphrase the use of ‘spiritual, intellectual, moral, social and cultural development of pupils to (SIMSC). My subject is Physical Education (PE). I am referring to different types of PE: PE in the historical public education sense, and the similar games of today’s independent school system and PE as a subject that encompasses “exercise, sports and activities out of school” (PE national curriculum, 2013). PE does not have just to be part of the explicit school curriculum but it can represent something much more implicit that occurs in sport participation. PE may refer to the compulsory National Curriculum (NC) KS3 subject, the KS4 foundation subject (Gov.uk, 2017) or the PE GCSE which differs greatly. The GSCE is increasingly more theoretically scientifically based (up to 70%) with little practical. The KS3/ KS4 compulsory subject is more practical. I will also consider how PE develops citizenship, as this discipline can encompass all of the developmental characteristics. I expand on the discussion within the confines of this question and the ambiguity of how SIMSC can be defined, taught and measured. My of definition ‘explicit’ in this essay represents an obvious or direct learning outcome that is mentioned. Within this essay I have used implicit in two ways: the idea of implicitly learning without intending to and when SIMSC can be developed without it being a direct consequence of the PE.

“PE can encourage individual initiative and effort, as well as teamwork skills” (QCA, DFEE, 1998, p.45). Is this PE contributing to SIMSC? After defining the meanings of SIMSC education in this context, exploring the 1998 and 2013 NC’s of PE, this question could be more answerable. Ultimately I recognise that dependant on the differing definitions; it may affect how much I decide PE contributes to SIMSC curriculum. I will draw on the professional body, the Association for Physical Education’s (AfPE) published subject content who demonstrate SMSC is part of the curriculum. I acknowledge historical aspects of PE within this discussion (McIntosh, 2013) as I recognise PE and its relation to SIMSC and citizenship is concurrent throughout historical PE. Considering varying viewpoints on the subject I draw on the work of scholars who accept PE can contribute to SMSC education (Bailey, 2005,2014), (Laker, 2002). This understanding is evident within the AfPE‘s definition for SMSC and citizenship education (Leach, 2015). In contrast some hold that PE does not contribute to SIMSC education (Laker, 2002). Some struggle to learn explicitly anything other than the physical requirements within PE. Whilst I cannot examine all the variables of SIMSC education within the constraints of this essay I will be exploring this topic through my own (albeit somewhat narrowed) viewpoint and experiences. This is not unlike the 2005 lecture, ‘Miss Goddard’s Grave’ where Pullman said we “bring our own preconceptions and experiences to an encounter” (Pullman, 2005, p.2). Thus I bring my experiences of being a PE pupil, a PE teacher, and a student of education (to this discussion).

An understanding of SIMSC can be problematic with the multiple definitions that are available, though it can be linked to developing an understanding of rights, duties and relationships with others as part of British values. To aid clarity throughout, I have adapted the Ofsted based definitions of Social, Moral, Spiritual, and Cultural (SMSC), (Doingsmsc.org.uk, 2015). Whilst I consider not all educationalists agree with Ofsted’s classifications I have modified them to suit my beliefs and experiences. SMSC has formed an important part of Ofsted’s inspections (particularly within section five) where schools must demonstrate they promote British values through SMSC (DFE, 2014). Appendix C shows the how Ofsted is ‘Defining SMSC development’ (Ofsted,2016).My definitions are in reference to this document. Spiritual is based on “Exploring [sic] beliefs and respecting others experience, faith, feelings and values”. Moral is being able recognise “right and wrong; respecting the law, understanding consequences and offering reasoned views”. Social is “using a range of skills to participate in the local community; appreciate diverse viewpoints; participate, volunteer and cooperate, engage with the ‘British values’ of democracy, and show respect and tolerance”. Cultural can be “appreciating, respecting, understanding and accepting cultural influences, participating in cultural opportunities and celebrating diversity” (Ofsted, (2016), p.35). Thus when I consider PE and the effects on SMSC it is to these definitions I will be referring.

Intellectual development can be even more problematic in its definition. Unlike SMSC it is not widely associated with British values. I am thus principally going to address intellectual development separately, specifically as it does not form part of the SMSC acronym. There are differing psychological and philosophical explanations for intellectual. In children’s PE development intellectual can be physical, social, emotional, cognitive (Slater and Bremner, 2003) and includes sport specific language. It can be focused on how a child understands their environment and gains knowledge. This can be developing skills such as concentration or reasoning. In PE (particularly within GCSE) the intellectual side of the subject enables pupils to learn theories and try them out practically or apply to theories to real life sporting examples.

Not all agree PE contributes towards SIMSC development. “Critical pedants argue the subject can contribute to the hidden curriculum that allows social injustice, prejudice and inequality” (Larker, 2002, p.2). Therefore with these described negative attributes it cannot positively contribute to a SIMSC. Social and cultural developments are based on relationships and understandings with one another (Oxfam, 1997). When these are unequal the developmental learning may not occur. If pupils do not enjoy, engage with or participate in PE (Capel & Whitehead, 2010) they may not explicitly or implicitly develop themselves as an outcome. However, it can be argued this is true for many interactions young people have. This exclusion does not just occur within PE, some pupils “experience problems commonly… with exclusion” (Jermyn, 2001, p.4). This is can be prevalent when young people have to work socially. If PE lessons exclude individuals, they will not be able to actively contribute towards an individual’s SIMSC development. It is clear that when attempting to assess PE’s contribution it cannot always affect all individuals, so I will continue to analyse a much wider basis for assessing these connections.

Although SIMSC is not mentioned specifically in the 1998 and 2013 PE NC there are many aspects of the development or inclusion of skills that can be under SMSC. The 2013 PE NC declares PE must “build character and embed values such as fairness and respect” (DFE, 2013, p.2, p.5). The concepts respect and fairness can connect with social relationships and respect for difference, these are components of social and cultural development, and they can be demonstrated in lessons and sports implicitly. Within the 1998 NC there is the addition of outdoor and adventurous activities where a focus was “identifying the roles and responsibilities of individuals within a group” (QCA/DFE, 1998, p.112). This is more explicit of how social development is to be attained within PE activities. Paralleled to the concise 2013 PE NC the 1998 NC is lengthier and more personal. It contains individual’s quotes such as: Lucy Pearson, ex England Cricketer and teacher. She mentions PE is about “learning how to work with and to respect others” (QCA/ DFEE, 1998, p118)”. This inherent part of PE is important for SMSC development. An awareness of working with others with difference of belief, cultural, social and even moral circumstance is integral to SMSC growth. To simplify this politically it seems that SMSC is important in education in both the 1998 (Labour government) curriculum and the 2013 (Conservative government) curriculum. Despite a change in political party it still has relevance.

The AfPE is influential within school PE development at local and national level as it responds to governmental changes on PE on behalf of its membership body. It publishes advice and resources based on the NC. They highlight PE “contributes so much to areas such as SMSC” (AfPE, 2015).

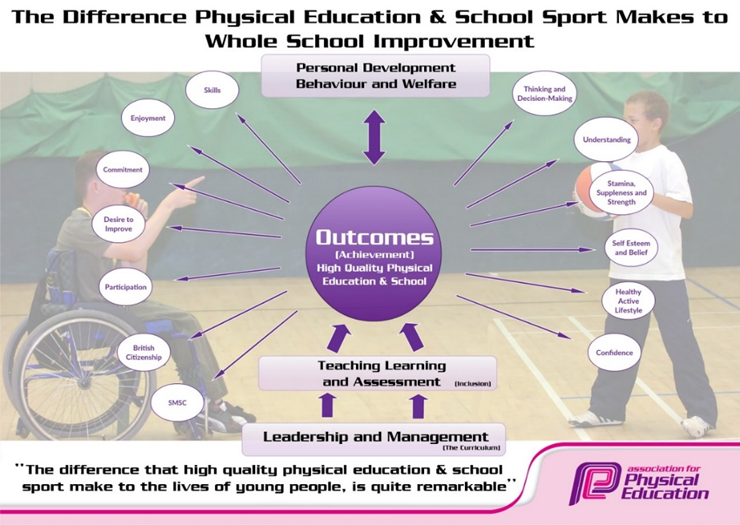

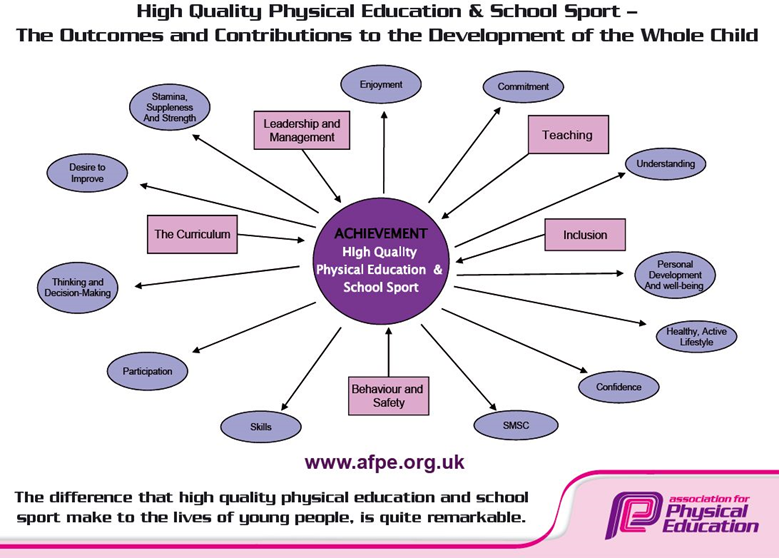

This is also evident in their published “School Sport leads To Whole School Improvement”. They state “Taking part for the individual requires confidence, skills, knowledge, the ability to manage time and relationships and having a group of supportive friends and companions, including some who share the same desire to take part” (Leach, 2015, p.80) . In addition this is apparent in their 2015 posters: The Difference PE & School Sport Makes to Whole School Improvement (fig,1) and ‘The outcomes of PE to the whole child’ (fig,2). Both posters explicitly exhibit the connections to SMSC. Neither poster clearly mentions the intellectual development. For me, the AfPE are important in my teaching and the realisation of the PE curriculum. They trust PE to have multi-disciplinary effects in the education of the individual and believe that SMSC is one of these outcomes. I concur that PE can actively contribute to SMSC.

It is worth noting PE and the development of an individual’s SIMSC have been connected since the ancient Greeks (Mandell, 1999; Kyle 2014) and more recently from nineteenth century Public education. In both historical educational systems PE formed an important part of the total education (McIntosh, 2013). Plato supported Physical Education and warned against merely training the mind. It is thought Plato originated the belief “sport builds character”(Reid,2007). This ‘character’ can be linked to the origins of civic moral duties and citizenship in community within Ancient Greece (Heater, 2003). Therefore Plato’s emphasis on the physical also has a cultural link. A connection can be also drawn with the Spartans where there was also an important link between physicality and citizenship. Sparta believed the physically strong and active strengthened the moral, cultural and civic pride of the nation (Wooyeal and Bell, 2004).

This can link to the idea that young people playing can physically develop and learn through the social self (Rosseau, 1974). Although this could link to the all-round and even cognitive intellectual this is not my focus. In the nineteenth century PE was seen as a developmental part of the education, additional to a ‘gentlemanly pastime’ (Shrosbree, 1988). Aside from the idea that physical activity can improve intellectual ability in other lessons ,it begun to be seen as a contributor to pupil’s intellectual growth in its own right.

In the nineteenth century, the ideal of muscular Christianity and the public schools athleticism was supported by ‘1864 Clarendon Commission’. It stated that “the football and rugby pitches…. were not merely for amusement…. they help form many of the social qualities and virtues” (Shrosbree,1988). This demonstrates a link in historical sport education to SMSC development. This is not just a former philosophy of PE, a link could be also made to the views of the previous Prime Minister David Cameron during a public addresses on education. The BBC in 2011, reported he said “Frankly, we need a… much more active, muscular liberalism” (p1). Cameron later said (In June 2014) the country should be “far more muscular” in promoting its values and institutions. He endorsed “British values” in the classroom (Cameron for MailOnline, 2014). This idea of muscularity (moral, spiritual, social development) can link to both nineteenth century and the recent PE curriculum. Currently in education this can also be relevant with the conservative educationalists and Ofsted who are keen to develop ‘character’ in schools across the whole curriculum (Gov.uk, 2015). This can draw the distinction in physical education that sport can impact character. This ‘character’ can be seen as specifically a component of moral development.

Notably, it is not just PE contained within schools that can build young people’s social and moral character. The idea of PE is to encourage activities throughout life and to be able to understand and apply the long-term health benefits of physical activity throughout life (DFE, 2013, p.3). Learning outside the lessons is part of a PE, as it contributes to the whole holistic education. Internationally hosted and televised events can implicitly form part of PE. It is events like the 2012 London Olympics that can be part of an informal education in aiding development of moral character (Reid, 2006). Within England and the UK many of the population felt united by the hosting and support for our home nation. This links to the social and moral development, akin to being a citizen and contributing to the whole society (Aoyagi et al., 2008). This can be true for both the athletes and support teams, or those that contribute by spectating. There were also those that ‘Gamesmakers’ that volunteered. Volunteering is a component of social development. Volunteering can also be seen as participating in cultural opportunities like the Olympics as an active, participating citizen (Eley and Kirk, 2002). The London Olympics impacted in school PE teaching when a triumphant international profile of sport in the games gave school sport a boost. Prior to 2012 the was a Wenlock and pre-Olympic movement in the UK (Penney, 2005) where money was given (£1.5 billion) for “sports for all”. It was reasoned to “ensure good behaviour and citizenship in society” (Penney,2005, p.6). Although this moral development cannot be easily measured it is clear high profile events can influence citizens’ behaviour.

The media has a large influence, alongside the prime televised events as to how sports contribute to our understanding of values, particularly moral ones. In 2012, Oscar Pistorius was celebrated as a disabled athlete fairly competing in able –bodied sport. In 2012 as viewers we were to value his hard working attitude and training ethic, achieving against the odds. This can be spiritual development “respecting others experience and values” (Ofsted, 2015). Even though he was not a Brit he was celebrated, socially, morally and culturally as a London Olympic hero (Tyng, 2014). In retrospect however, after his Villainous transformation in the media, it makes me question whether the values I gained 2012 still stand? I merely speculate but does that mean that some SMSC values are only temporary and not always fixed? Or as ever, it is just hard to pinpoint?

Outside the PE classroom, but still representing the school by participating in teams, the development of SMISC can be aided. It is like a type of active citizenship that can be promoted through team games (O’Donovan et al., 2010). It can be observed that in team sports the participation and value of playing the game for enjoyment are a main aim. Whilst winning in sport is significant, it does not have to be about winning at all costs. Taking part is more important. With sport as a microcosm of society (Frey and Eitzen , 1991), I believe this is a vital lesson that must be learnt. Participation can make greater contribution to society than a mere win can. Reflecting on my own PE this is something that I have learnt in my sporting engagements. Being a part of large events can contribute to a social, cultural and spiritual development. In an annual large rowing race in London of up to 3,000 crews, it was about the participation for my team, achieving our personal best as a crew -not gaining medals at the event.

The idea about participation is reflected in my current (independent) school’s games options. Our games options are varied much more so than the traditional three term system like: Rugby, Hockey and Cricket. Students are able to choose activities like yoga and skateboarding, they partake in these for enjoyment and development, not competition. Yoga can develop pupils spiritually as it aids mental practice where emotional stresses are reflected upon (Duff, 2003). It can also include meditation as a main goal of Yoga is to develop spiritually (Goyeche, 1979). It can also be argued that this development of stress management can be a form of emotional intelligence, where pupils have the capacity to be able to be aware of and control their emotions.

The idea of PE (as an education for more than the physical self) despite originating in historical education has been arguably more incorporated ‘post-millennium’ (Laker, 2002). It has reformed to emphasise “the society’s and government’s new focus on citizenship …and aspects of a young person’s growth” (Laker, 2002, p.2).This PE is for social responsibility, moral behaviour and democracy (Lupton, 2007) and the “expected role that the subject can fulfil is complementary to current educational trends and practices and to the political ideal currently being proposed” (Laker,2002, p.3). I note the current PE NC (since 2013) is less prescriptive and as a consequence it possibly could be harder for some teachers to implement all the SMISC aims when PE teaching.

I am concluding it is based on the assumption that PE is part of the whole holistic physical education of pupils, (informal and formal education) not just merely confined to what schools can offer us in the statutory one lesson a week at KS3. PE can contribute to a SMSC education. Traditionally PE and the SMSC aspect of the subject can be seen from ancient Greeks and a nineteenth century public school education (Mandell, 1999), (Kyle 2014) (McIntosh, 2013) (Bailey, 2014). I have identified in my learning and teaching that pupils’ involvement in PE (and many aspects of education) is unequal and this impacts outcomes learnt in PE (including SIMSC). I do not believe that it is worth discounting the contribution that PE could have to SMSC due to the unequal outcomes of education. Despite this unfortunate circumstance, I largely discredited this antithesis. I have concluded that the explicit (where SMSC is a stated learning outcome) and implicit (where the values of SMSC are outcomes that can be learned) can be evidenced by the national curriculums (1998, 2013) and the AfPE as well as other scholars (Laker, 2002) (Bailey, 2014).

Overall with my analysis on the intellectual development is less clear cut. It can be harder for some of the practical, statutory PE lessons within their constricted time to actively contribute to the intellectual development of individuals. It is easier to assess how PE GSCE contributes with the theory, demonstrating a practical application to knowledge and therefore the intellectual development. I recognise not all pupils will undertake this option, so the basis for the intellectual development can be seen to be reduced. I hope this thesis provides an insight into the means that PE can contribute to SMSC development. It is up to us, the teachers, to ensure PE continues to develop the ‘whole’ pupil.

References:

- Bailey, R. (2005). Evaluating the relationship between physical education, sport and social inclusion. Educational review, 57(1), 71-90.

- Bailey, R. (2014). Teaching values and citizenship across the curriculum: educating children for the world. Routledge.

- BBC News,. (2011). State multiculturalism has failed, says David Cameron – BBC News. Retrieved 4 February 2016, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-12371994

- Cameron for MailOnline,. (2014). DAVID CAMERON: British values aren’t optional, they’re vital. Mail Online. Retrieved 18 February 2016, from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-2658171/DAVID-CAMERON-British-values-arent-optional-theyre-vital-Thats-I-promote-EVERY-school-As-row-rages-Trojan-Horse-takeover-classrooms-Prime-Minister-delivers-uncompromising-pledge.html

- Capel, S., & Whitehead, M. (Eds.). (2010). Learning to Teach Physical Education in the Secondary School: A companion to school experience. Routledge.

- DFE,. (2013). Secondary National Curriculum Physical Education (1st ed.). GovUk. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239086/SECONDARY_national_curriculum_-_Physical_education.pdf

- DFE,. (2014). Promoting fundamental British values as part of SMSC in schools. Departmental advice for maintained schools . Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/380595/SMSC_Guidance_Maintained_Schools.pdf [Accessed 24 Feb. 2017].

- Doingsmsc.org.uk. (2015). What is SMSC?. [online] Available at: http://www.doingsmsc.org.uk/ [Accessed 24 Feb. 2017].

- Duff, L., 2003. Spiritual development and education: A contemplative view. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 8(3), pp.227-237.

- Eley, D., & Kirk, D. (2002). Developing citizenship through sport: The impact of a sport-based volunteer programme on young sport leaders. Sport, Education and Society, 7(2), 151-166.

- Gov.uk,. (2015). Nicky Morgan discusses the future of education in England – Speeches – GOV.UK. Retrieved 18 February 2016, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/nicky-morgan-discusses-the-future-of-education-in-england

- Gov.uk. (2017). The national curriculum – GOV.UK. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/national-curriculum/key-stage-3-and-4 [Accessed 26 Feb. 2017].

- Goyeche, J.R.M., 1979. Yoga as therapy in psychosomatic medicine. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 31(1-4), pp.373-381.

- Heater, D. (2003). A history of education for citizenship. Routledge.

- Jermyn, H. (2001). The arts and social exclusion: A review prepared for the Arts Council of England (pp. 1-43). London: Arts Council of England

- Kyle, D. G. (2014). Sport and spectacle in the ancient world (Vol. 5). John Wiley & Sons.

- Leach, Simon. (2015) “Association For Physical Education:The Difference PE & School Sport Makes To Whole School Improvement”. AfPE.org.uk. Web. 1 Feb. 2016.

- Laker, A. (2002). Beyond the boundaries of physical education: Educating young people for citizenship and social responsibility. Routledge.

- Lupton, D. (1999). ‘Developing the “whole me”’: Citizenship, neo-liberalism and the contemporary health and physical education curriculum. Critical Public Health, 9(4), 287-300.

- Mandell, R. D. (1999). Sport: A cultural history. iUniverse.

- McIntosh, P. C. (2013). Landmarks in the history of physical education (Vol. 22). Routledge. (1st edition 1957)

- O’Donovan, T. M., MacPhail, A., & Kirk, D. (2010). Active citizenship through sport education. Education 3–13, 38(2), 203-215.

- Ofsted,. (2016) Guidance School inspection handbook. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspection-handbook-from-september-2015 [Accessed 24 Feb. 2017].

- Oxfam, A. (1997). A curriculum for global citizenship. Oxfam GB.

- Penney, D. (2005). Sport education in physical education: Research based practice. Psychology Press.

- Physical Education Matters Autumn (2015) Official Journal of the Association for Physical Education. Association for Physical Education, Vol.10, No.3

- Pullman, P., 2005. Miss Goddard’s Grave. University of East Anglia Lecture. Dec, 13.

- QCA (1998) Education for Citizenship and the Teaching of Democracy in Schools: Final Report of the Advisory Group on Citizenship, London: Qualifications and Curriculum Authority

- QCA/DFEE,. (1998). The National Curriculum: Handbook for secondary teachers in England (1st ed.). Gov.uk. Retrieved from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/http://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/QCA-04-1374.pdf

- Reid, H. L. (2006). Olympic sport and its lessons for peace. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 33(2), 205-214.

- Reid, H.L., 2007. Sport and moral education in Plato’s Republic. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 34(2), pp.160-175.

- Rousseau, J. J. (1974). The essential Rousseau: The social contract, Discourse on the origin of inequality, Discourse on the arts and sciences, The creed of a Savoyard priest.

- Shrosbree, C. (1988). Public schools and private education: the Clarendon Commission, 1861-64, and the Public Schools Acts. Manchester University Press.

- Slater, A. & Bremner, G. (2003) An Introduction to Developmental Psychology. Blackwell. Pages 154,155 & 156 .

- Tyng, O. L.(2014) Analysing Media Communication 2014.

- Wooyeal, P., & Bell, D. A. (2004). Citizenship and state-sponsored physical education: Ancient Greece and ancient China. The Review of politics, 66(01), 7-34.

Appendix:

A: Fig.1: AfPE Poster: The Difference PE & School Sport Makes to Whole School Improvement, Accessed from: http://www.AfPE.org.uk/images/stories/New_2015_Outcomes_Poster.jpg

B: Fig2: AfPE Poster: The outcomes of PE to the whole child Accessed from: http://www.AfPE.org.uk/images/stories/HQ_PE_Outcomes_Poster.jpg

C: Appendix C : Defining spiritual, moral, social and cultural development from Section 5. School inspection handbook ,DfE,August 2016, No. 150066

Defining spiritual, moral, social and cultural development

136. The spiritual development of pupils is shown by their:

ability to be reflective about their own beliefs, religious or otherwise, that inform their perspective on life and their interest in and respect for different people’s faiths, feelings and values

sense of enjoyment and fascination in learning about themselves, others and the world around them

use of imagination and creativity in their learning

willingness to reflect on their experiences.

137. The moral development of pupils is shown by their:

ability to recognise the difference between right and wrong and to readily apply this understanding in their own lives, recognise legal boundaries and, in so doing, respect the civil and criminal law of England

understanding of the consequences of their behaviour and actions

interest in investigating and offering reasoned views about moral and ethical issues and ability to understand and appreciate the viewpoints of others on these issues.

138. The social development of pupils is shown by their:

use of a range of social skills in different contexts, for example working and socialising with other pupils, including those from different religious, ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds

willingness to participate in a variety of communities and social settings, including by volunteering, cooperating well with others and being able to resolve conflicts effectively

acceptance and engagement with the fundamental British values of democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs; they develop and demonstrate skills and attitudes that will allow them to participate fully in and contribute positively to life in modern Britain.

139. The cultural development of pupils is shown by their:

understanding and appreciation of the wide range of cultural influences that have shaped their own heritage and those of others

understanding and appreciation of the range of different cultures within school and further afield as an essential element of their preparation for life in modern Britain

knowledge of Britain’s democratic parliamentary system and its central role in shaping our history and values, and in continuing to develop Britain

willingness to participate in and respond positively to artistic, musical, sporting and cultural opportunities

interest in exploring, improving understanding of and showing respect for different faiths and cultural diversity and the extent to which they understand, accept, respect and celebrate diversity, as shown by their tolerance and attitudes towards different religious, ethnic and socio-economic groups in the local, national and global communities.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal