Evaluation of Game-Based Learning Tools for Students

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Education |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3306 words | ✅ Published: 03 Nov 2020 |

Rationale Behind My Resource

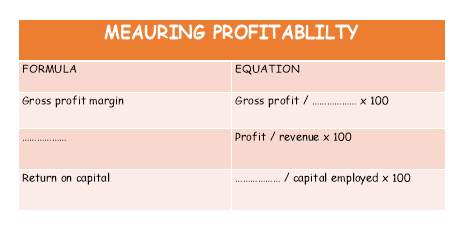

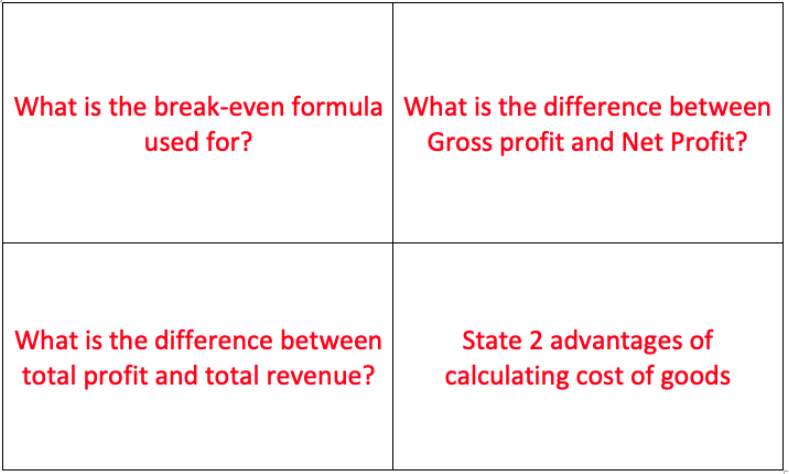

Recent literature states that game-based learning is the means of taking an idea and creating an exercise to produce that idea in a manner that is engaging, motivating, challenging, and effective and has quantifiable learning objectives (Tham & Tham, 2012). Based on this this definition I have thought about how it would be possible to use game-based learning as a pedagogical tool to benefit the process of students’ learning. In addition to this, the business curriculum requires students to memorise a variety of key words, theories and financial formulas (Pearson Education, 2016). As a result, my resource focuses on learning and recalling the vast amount of formulas which have to be studied for the BTEC Business syllabus (Brant and Davies, 2005) but in a game-based learning format.

Gee (2007) ranks the field of game-based learning among the most important power of play to improve learning. Other literature further supports this by stating that there are a number of factors being demonstrated as to why games are effective in learning environments (Jan L. Plass, Bruce D. Homer & Charles K. Kinzer, 2015). One of these key factors is motivating the pupils. The reason for this is that games have shown that motivated pupils stay engaged over long periods through a series of game features (Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Rotgans & Schmidt, 2011). In the case of my resource, the features that are being used as incentives are scoring points and as a result improving a pupil’s position on the leader board. Improving the cognitive load is another feature of conducting game-based learning (Woo, 2013). The psychiatrist William Glasser created the Glasser’s Choice Theory (1999) and in it recognised fun to be one of the basic needs that drives working memory. As a result, for genuine learning to occur and for learners to remember the material for a long time, fun is necessary (Willis, 2007). Thus, my resource will help the pupils to incidentally increase the level of cognitive load while playing and having fun (Tham & Tham, 2012).

Lastly, another factor to consider for game-based learning is that it allows for a high level of student engagement (Prensky, 2005). Prensky (2005) states that when games are used correctly in a classroom, they can provide lessons that are more learner-centred, more enjoyable, and therefore more engaging. For example, the Plass, Homer, et al. (2013) study describes that a competitive game designed for school pupils increased their interest, enjoyment, and mastery goal orientation. Furthermore, from analysing the Interaction model of learner activity (Domagk, Schwartz, & Plass, 2010), my resource uses cognitive engagement section of the model (i.e., mental processing and metacognition). The resource does this through engaging the pupil by remembering the answers on the flash cards. Domagk, Schwartz, & Plass (2010) suggests that games that do not achieve cognitive engagement are not likely to be effective in helping the learner achieve their learning goal.

As the use of game-based learning is becoming increasingly popular due to the high growth in the number of studies on game-based learning and its effectiveness (Hwang & Wu, 2012). As a result, this method is receiving more credibility by offering significant potential to increase pupils learning (Papastergiou, 2009; Huang, 2011). In particular, I believe my resource can be beneficial to pupils studying BTEC Business. The use of games can overcome the issues identified in the literature; that trying to memorise and recite formulas for academic purposes can be tedious and result in demotivation (Kim, 2009). Pupils need to learn these formulas if they are to answer the finance questions in their exam correctly. Furthermore, learning these formulas will be beneficial for the future of the pupils if they are to work in the financial sector or create their own business, which is highly likely as business students. I expect that my resource will achieve teacher standards 3 and 4 (Department for Education, 2011), specifically securing the subject knowledge of the finance area of the curriculum, whilst maintaining interest. Combining this with a love of learning and curiosity to contribute to the development of an engaging resource.

Use Of The Resource

As stated previously my resource was created and used for the purpose of the BTEC Business course. In particular my year 11 class, learning Pearson BTEC Business Level 2, in preparation for their Unit 2: Finance for Business exam. This unit is highlight in the scheme of work in Appendix A. The resource itself contains a number of flash cards, which covers all the financial formulas that the students have to learn for their exam. Wissman et al (2011) stated that pupils would benefit from the utility of flashcards for learning a vast amount of material. The more correct answers the pupils gave, the more points are accumulated which in turn increased the likelihood of them winning their game. From this I created a league table (Appendix B) to log the points and a line graph (Appendix C) displaying the amount of points scored each week from each pupil. As a result, I could assess the pupils progress week by week and to what extent they have developed their knowledge on these financial formulas.

Overall, I feel the use of the flash cards made the resource a success, which is further supported in my appendices. During my placement at the school I developed a strong relationship with the class and therefore I felt confident in delivering this new resource to them whilst creating a safe environment. The drawback, however, was that the pupils only had a small amount of opportunities to complete a set of fixtures for the resource. The fact that the class could only complete five rounds of matches meant the pupils could only practice the questions five times. Therefore, the pupils will have had less chance to learn every formula that is in the resource, which means more progress could have been made with more time available.

Critical analysis of the resource

On reflection, I feel my resource was effective at developing the pupil’s knowledge of the BTEC Business financial formulas. The evidence to support this are shown in the results on Appendix D. As stated previously I collected the points scored by each pupil weekly. Appendix D is a result of all the points scored in total by week, showing the progress the class main as a whole over the 5 weeks. From analysing these figures, it is clear that the pupils have progressed dramatically from week 1 to week 5. This is due to the fact that 57 more points were scored at week 5 compared to week 1. Furthermore, a consistent increase in total points scored week by week quantitatively supports the effectiveness of the resource. In addition to this, there are 2 pupils that made a dramatic improvement in the 5 weeks. As Appendix E shows, pupil 1 and 2 consistently increase their score week by week with pupil 1 scoring the highest score out of any of the pupils during the 5 weeks.

In contrast, the resource was only beneficial to some degree as it only assesses factual knowledge and but not what the application of these formulas means for a business, which is critical if pupils are to earn high marks in their exam (Pearson Examiner Report, 2015). This could mean that the pupils may struggle to apply the knowledge learnt from the resource to exam questions with higher marks available. Chin and Osbourne (2008) argues that questions that require pupils to critically think and problem solve are far more beneficial to assess students’ progress than factual recall questions. Therefore, it would have been beneficial to add some flashcard questions that focus on the application of the formulas to ensure critical thinking skills are developed as well as knowledge.

Furthermore, certain pupils did not make the same level of progress compared to the rest of the class. The main reason for this was that some pupils struggled to work with other pupils in the class. This was due to conflicting characters in the class and as Tuckerman (1964) stated that conflict is a natural part of learning but if students don’t learn to overcome conflict then they will limit themselves of the cognitive benefits of working collaboratively. From acknowledging this study and analysing the data in Appendix D and E, it is clear that pupils 6 and 10 struggled to work collaboratively with their opponents during the game, resulting in large fluctuations to their score’s week on week. This is further supported by pupil 10 in particular who would complain if their opponent wasn’t a friend of theirs, which would then lead to them becoming disinterested in the upcoming game and less motivated to participate (Chan and Chen, 2011).

The impact of gender on pupil’s participation, motivation and engagement in a in this game-based learning resource became apparent from the initial stages. In this particular class the gender split was 12 males and 4 females showing that the majority of the class were male pupils. A study found that males are more likely to benefit from the use of a competitive game in the classroom (Griffiths and Hunt, 1995). Yen et al (2011) supports this further by stating that females tend to be stand and watch during a game-based exercise compared to their male classmates, which indicates a stronger link to engagement.

Another issue with the resource was the lack of prior knowledge the pupils had on reciting the financial formulas. Ausubel (1968) stated that a pupil’s prior knowledge is one the most important factors in learning. Further literature suggested that in order to have a more engaged pupil, prior knowledge and experiences must be used (Hattie and Yates, 2013). This literature is further supported by the results shown in week 1 (Appendix E). The larger the increase in total points scored by the pupils, after the pupils had taken part in the resource twice. For example, the points differences between weeks 3, 4 and 5 were +30 and +25 respectively. Thus, indicating that the pupils showed more progress once they had prior knowledge learnt from weeks 1 and 2.

The final limitation of my resource was the large amount time between the resource being used, which ultimately affect the pupil’s memory of the formulas. Banham (2017) suggests that pupils will have forgotten a large amount of information they learnt within a day of learning it. As the time between each occasion that the resource was used was 7 days this could have impacted on the pupil’s ability to memorise the formulas. Banham (2017) goes on to say that in order for the information to integrate into the long-term memory, constant revisiting of the information is paramount. The timing of the resource can also have an influence on the effectiveness of the resource as the BTEC pupils have to complete large amount of coursework during their course. Therefore, I was also having to swap to other topics in the specification in order for the pupils to complete sections of their coursework successfully. After week 2 the class had moved onto learning about enterprise and entrepreneurship, so it could have proved difficult to memorise the financial formulas. This vast amount of information could lead to cognitive overload resulting in the pupil being unable to process this information (Shibli and West, 2018).

Overall, the initial purpose of my resource was to improve pupils’ factual knowledge of the financial formulas required in the BTEC Business syllabus, and on reflection after analysing the whole class data (Appendix B, C, D and E), I can deduce that a significant improvement was made, with 100% of the class improving their score from week 1 to week 5 as a result of my resource.

Further Development

Despite my resource showing that was a definite improvement of pupils’ factual knowledge on the financial formulas for BTEC Business. The class struggled to engage in the first week due to the lack of prior knowledge. Therefore, I feel that it is essential to give some initial support to the students in order to accelerate learning during the first week of using the resource. As a result, I have created support sheets that I will hand out to the pupils to help them before and whilst using the resource (Appendix F). These fill-in-the-blank support sheets are a beneficial way to not only assess prior learning but to help pupils retrieve learnings from their long-term or short-term memory (Butler and Roediger, 2007). Once I feel that an individual pupil has sufficient knowledge, I will encourage them to use the resource without the support sheets, thus improving their factual knowledge of the formulas further. I feel that the use of these support sheets will help engage the pupils from the outset and kickstart the learning progress.

As previously discussed, whilst the resource was extremely beneficial at enhancing a pupil’s factual knowledge it did not drive the pupil’s to critically think about the application of these formulas. Hence, I have produced a sample of extra flashcards that include exam style questions in order to offer them the crucial practice they need to answer the longer exam questions (Appendix G). These extra flash cards will give the pupils the necessary capabilities to complete and achieve higher marks in the exam.

The resource is a game-based learning exercise and is centered around working in pairs, which required a certain amount of teamwork. From the start of using the resource it became apparent that some students struggled to work with others. Capel et al (2016) stated that not all students learn in the same way so teamworking may not be a good method of learning for some pupils. This led to a few students becoming disinterested in participating and ultimately not only lead to their lack of engagement, but also affected their opponents’ contribution, due to the resource requiring one people to ask the questions and one pupil to answer. Newcomb and Bagwell (1995) discovered that friendship collaborations leads to a more effective task performance. In addition, Azmitia (1999) suggested that the psychological context of friends working together may be connected with productivity and learning benefits. Therefore, when I organise the use of this resource again for future practice. I may split the pupils into mini leagues that are compiled of groups of students that I know will work well together rather than a whole class league.

Overall, I am very pleased with the outcome of my resource. I feel it definitely improved pupils’ factual knowledge of the key financial formulas that have to be learnt for the Pearson BTEC Level 2 Business syllabus and in particular for their Unit 2: Finance for Business exam, taking place in February 2020. I have been able to quantitatively measure the degree of improvement on my year 11 BTEC class and this has enabled me to discover the further improvements that can be made to the resource in order to overcome the limitations stated previously. It has given me an insight into some of the challenges that I did not expect to face, such as, teamworking and lack of prior knowledge. Which have been extremely useful to understand and resolve as I progress as a new teacher. Moreover, I have learnt the importance of factual knowledge being taught to my pupils but also the application of this knowledge. This discovery has informed my future planning and development of the resource. I am eager to see how future classes develop their analytical and critical skills from the expansion of the resource.

References for the resource

- Howard-Jones, P.A. and Demetriou, S., 2009. Uncertainty and engagement with learning games. Instructional Science, 37(6), p.519.

- Speck, G. (2019). Secret Teacher: my students know all about exams but little of the wider world. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/2018/apr/14/secret-teacher-my-students-know-all-about-exams-but-little-of-the-wider-world

- Cropper, C., 1998. Is competition an effective classroom tool for the gifted student?. Gifted Child Today, 21(3), pp.28-31.

- Howard-Jones, P.A. and Demetriou, S., 2009. Uncertainty and engagement with learning games. Instructional Science, 37(6), p.519.

- Griffiths, M.D. and Hunt, N., 1995. Computer game playing in adolescence: Prevalence and demographic indicators. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 5(3), pp.189-193.

- Bruner, R.F., 2001. Repetition is the first principle of all learning. Available at SSRN 224340.

- Guskey, T.R., 2018. Does pre-assessment work. Educational Leadership, 75(5), pp.52-57.

References for the commentary

- Ausubel, D.P., Novak, J.D. and Hanesian, H., (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view.

- Azmitia, M., (1999). Peer interactive minds. Learning relationships in the classroom, pp.207-233.

- Banham, D. (2017). ‘Raising attainment’ in Davies, I. (eds) Debates in History Teaching, 2nd ed. Routledge: Oxon, pp.215-226.

- Brant, J. and Davies, P., (2005). Business, economics and enterprise: teaching school subjects 11-19. Routledge.

- Brooks, V., Abbott, I. and Huddleston, P. eds., (2012). Preparing to teach in secondary schools: a student teacher’s guide to professional issues in secondary education. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Butler, A.C. and Roediger III, H.L., (2007). Testing improves long-term retention in a simulated classroom setting. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4-5), pp.514-527.

- Capel, S., Leask, M. and Younie, S. (2016). ‘Meeting Individual Differences’ in Capel, S. et al. Learning to Teach in the Secondary School: A companion to school experience. 7th ed. Routledge: Oxon, pp.215-216.

- Chan, L.H. and Chen, C.H., (2010). Conflict from teamwork in project‐based collaborative learning. Performance Improvement, 49(2), pp.23-28.

- Chin, C. and Osborne, J., (2008). Students’ questions: a potential resource for teaching and learning science. Studies in science education, 44(1), pp.1-39.

- Department for Education (2011). Teachers’ Standards. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/283566/Teachers_standard_information.pdf (Accessed: 4th January 2020).

- Domagk, S., Schwartz, R.N. and Plass, J.L., (2010). Interactivity in multimedia learning: An integrated model. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), pp.1024-1033.

- Gee, J.P., (2007). Good video games+ good learning: Collected essays on video games, learning, and literacy. Peter Lang.

- Glasser, W., (1999). Choice theory: A new psychology of personal freedom. HarperPerennial.

- Hattie, J. and Yates, G.C., (2013). Visible learning and the science of how we learn. Routledge.

- Howard-Jones, P & Jay, T., (2016). ‘Reward, learning and games‘, Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, vol. 10, pp. 65 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.04.015

- Kim, B., Park, H. and Baek, Y., (2009). Not just fun, but serious strategies: Using meta-cognitive strategies in game-based learning. Computers & Education, 52(4), pp.800-810.

- Newcomb, A.F. and Bagwell, C.L., (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 117(2), p.306.

- Plass, J.L., Homer, B.D. and Kinzer, C.K., (2015). Foundations of game-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), pp.258-283.

- Plass, J.L., O’Keefe, P.A., Homer, B.D., Case, J., Hayward, E.O., Stein, M. and Perlin, K., (2013). The impact of individual, competitive, and collaborative mathematics game play on learning, performance, and motivation. Journal of educational psychology, 105(4), p.1050.

- Prensky, M., (2003). Digital game-based learning. Computers in Entertainment (CIE), 1(1), pp.21-21.

- Pearson Education, (2016). Pearson qualifications. Available at: https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/BTEC-Firsts/Business/2012/Specification-and-sample assessments/9781446936085_BTECFIRST_L12_AWD_BUS_Iss3.pdf [Accessed 13 Jan. 2020].

- Pearson Examiner Report (2015). Available at: https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/BTEC-Firsts/Business/2012/External-assessments/Examiner-report-Unit-2-Nov-2015.pdf [Accessed 8 Jan. 2020].

- Rotgans, J.I. and Schmidt, H.G., (2011). Situational interest and academic achievement in the active-learning classroom. Learning and Instruction, 21(1), pp.58-67.

- Shibli, D. and West, R., (2018). Cognitive load theory and its application in the classroom. Impact Journal of the Chartered College of Teachingfrom.

- Tham, L. and Tham, R., (2012). Is game-based learning an effective instructional strategy to engage students in higher education in Singapore? A pilot study. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology (RCET), 8(1), pp.2-10.

- Tuckman, B.W., (1964). Personality structure, group composition, and group functioning. Sociometry, pp.469-487.

- Willis, J., (2007). The neuroscience of joyful education. Educational Leadership, 64(9).

- Woo, J.C., (2014). Digital game-based learning supports student motivation, cognitive success, and performance outcomes. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 17(3), pp.291-307.

- Wu, W.H., Hsiao, H.C., Wu, P.L., Lin, C.H. and Huang, S.H., (2012). Investigating the learning‐theory foundations of game‐based learning: a meta‐analysis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(3), pp.265-279.

- Wissman, K.T., Rawson, K.A. and Pyc, M.A., (2011). The interim test effect: Testing prior material can facilitate the learning of new material. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(6), pp.1140-1147.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Pupil 1

Pupil 2

Pupil 3

Pupil 4

Pupil 5

Pupil 6

Pupil 7

Pupil 8

Pupil 9

Pupil 10

Pupil 11

Pupil 12

Pupil 13

Pupil 14

Pupil 15

Pupil 16

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal