Analysis of Curriculum Approaches in Chinese Kindergardens

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Education |

| ✅ Wordcount: 4238 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

Introduction

Education in China has been held in high-regard ever since the time of Confucius; engrained in culture and tradition. Due to its size and population, many statements about China can be both true and untrue; rural areas are third-worldly and first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai are at the forefront of development on a global scale. Drawing from personal experience teaching in China for the past seven years, I have based the premise of my ideal school as being located in an expanding third-tier city, such as the one where I currently reside.

China has undergone immense cultural changes over the past thirty years and “there is evidence that rates of depression have increased over this same period” (Ryder, et al. 2012, p.683). Professor Zhang Ning, one of China’s leading psychiatrists has seen an unprecedented rise in patients suffering from work related stress, treating mostly white-collar workers and high achievers for occupational burnout (Al Jazeera English 2014). Mental illnesses in China carry a stigma and can bring shame to the family so often people hide it and allow it to go untreated (ibid.). To address this crisis, I suggest an educational model that develops emotional literacy in early childhood education.

The importance of early childhood education can be demonstrated by one of the most famous case studies within social science; the 1960’s Perry Preschool project in Ypsilanti, USA. The purpose of the project was to raise the intelligence of children from low-income backgrounds. The project collected data on children from three to four years old, compared to a control group of children who did not attend preschool. The research revealed that although the project did not do much in the long term to raise their IQ, it did reveal diverse results in terms of income and occupational prestige (see Tough 2012, Luster and McAdoo 1994). The Perry Preschool students were more likely to have finished high-school, be earning more than twenty-five thousand dollars a year by age forty, less likely to have a criminal record or to have ever lived on benefits (Tough 2012).

The project ultimately proved that early education really does matter. This was exhibited by the students involved appearing to make better choices later in life when compared to the control group. Once it has been proven pre-school education is beneficial, the natural progression is then to determine which approach is the most appropriate.

For the purpose of this assignment, the term ‘successful’ or ‘fulfilling life’ will be based on factors as described by Layard et al. (2014); income, relationships, educational achievement and perceived life-satisfaction. This paper will present a summary of research studies comparing approaches to early childhood education, the ideal pedagogy to use, and the perceived limitations of this in a classroom in China.

I will consider the arguments of what constitutes an ideal school, an optimum curriculum and exemplary teachers in the classrooms; as a successful school relies on these core aspects. I have used specific case studies, theories and statistics to support my ideas, whilst recognising the limitations of applying a westernised model in an eastern setting.

Values and Pedagogies

The clear understanding of core values that underline a school’s purpose predetermines the success of any educational establishment. The aim and purpose of education has long been discussed since the times of Socrates, with a view to developing self-directed ‘‘human beings living with beauty, living with wisdom, and loving the common good’’ (Castoriadis 1991, p. 123, cited in Grant 2012). Plato’s ethical approach towards education referred to this as flourishing life (Grant 2012).

By discussing the goals of a school’s curriculum, Becker and Birkelbach (2011) say that an effective school “should consider both the actual achievement and the future development possibilities for the students” (p. 4) and can use this to create a ‘definition of the situation’ where the vision and values are shared by the students and teachers. On this basis of future development possibilities, I will not only go on to discuss the efficacy of early childhood education and its influence in a context of academic or vocational success, but also as a means of providing the tools for a fulfilling life.

Inspired by the Perry Preschool project, the High/Scope Preschool Curriculum Comparison study through to Age 23 (Shweinheart and Weikart 1997) was conducted, also in Ypsilanti, using a sample of children from low-income backgrounds. The purpose of this project was to find out if benefits from early childhood education measured equally across various curriculum approaches. They chose three different styles which varied in degree between the child’s expected initiation and the teacher’s expected initiation; the Direct Instruction curriculum model, the Nursery School curriculum model and the High/Scope curriculum model.

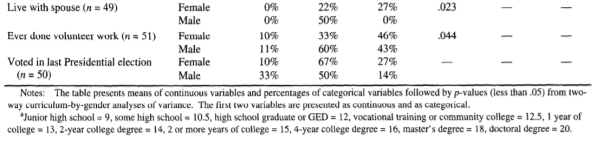

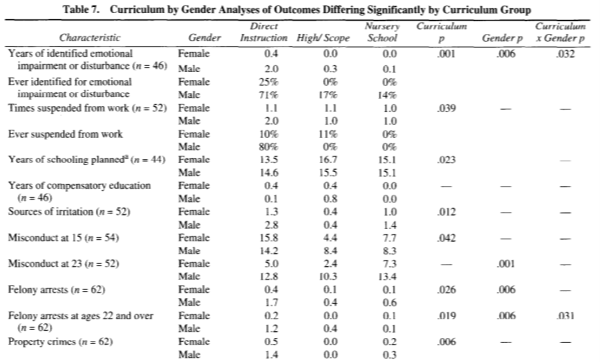

When the results of the variables were compared, the High/Scope model did the best overall. By the time they were twenty three years old, children educated by this model were the least likely to have a criminal record, most likely to be living with a spouse, had experienced fewer years of emotional impairment, and most likely to have done any volunteer work (see appendix 1).

To understand the success of the High/Scope model, a breakdown of what is happening in each of the three approaches is required. The Direct Instruction model is a programme learning approach, teaching academic skills that are assessed via IQ tests. This aligns with the approach found in the majority of kindergartens in China (Li, et al. 2016). Out of the three models, this requires teachers to initiate to the highest degree and the students the least. Paulo Freire (1970) referred to this pedagogy as banking education; asking the learner to ‘bank’ information that does not belong to them. The children are the most passive in this position, and it is assumed that children simply know less than adults. The goal is, therefore, to give them more information. When reviewing the results of the children who followed this formal approach thirty years later, they were far more likely to have a criminal record, unable to hold down jobs or maintain close relationships with family or spouses. Dr David Weikart, a researcher on the High/Scope comparison study, when referring to schools employing Direct Instruction methodology, noted “formal education at ages below age six certainly seems to be a negative experience for children, and I wouldn’t recommend it” (Upstart Scotland 2015).

The Nursery School model represented the child-centred approach. This is the approach inverse to the Direct Instruction model in terms of teacher and child initiation; here, the curriculum is led by the child’s interests and experiences. Children are active learners and lessons are situations facilitated by the teacher for the children to learn through their own discovery. It makes good sense to use the children’s interests as a starting point to increase the likelihood of engagement thus chances of successfully delivering a lesson. However, there is a risk that the child is unable to empathise or appreciate others’ opinions if only led by their own thoughts and feelings, “it is surely a very limiting education which focuses only upon the child’s interests” (Bottery 1990, p.12).

The High/Scope model was based on Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s constructivist theory. In this approach, “adults engaged children as active learners and arranged their classrooms in discrete, well-equipped interest areas” (Schweinhart and Weikart 1997, p.120). Their ethos was to always ‘plan–do–review’, work in small and large group activities and teachers engage children in intellectual, social and physical experiences. Such practices allow different learners to respond to audio, visual and kinaesthetic styles of learning and attempts to provide an inclusive, positive ethos.

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was renowned in the field of epistemology, and his work led to a breakthrough into understanding how people process information, develop language, think and solve problems. His work dispelled the assumption that children simply knew less than adults, as assumed in the Direct Instructive approach. When children are between the ages of two and seven, defined by Piaget as the ‘pre-operational stage’, “the child’s mental work consists principally in establishing relationships between experience and action; his concern is with manipulating the world through action” (Piaget cited in Bruner, 1976, p.34). The difficulty of the classic Direct Instruction approach is that the child is taught how and what things are, but does not understand the circumstances under which they change or stay the same, even though the child witnesses and is faced with these changes all the time (Elkind 1968).

There is a common misguided notion among parents that it is never too soon to start on academic skills. In Sweden, children have no formal education until they enter primary school at age seven with most not knowing how to read or write, yet they lead the literacy table in Europe. Swedish pre-primary education is centred on building community values and on play and relaxation (EDCHAT 2012).

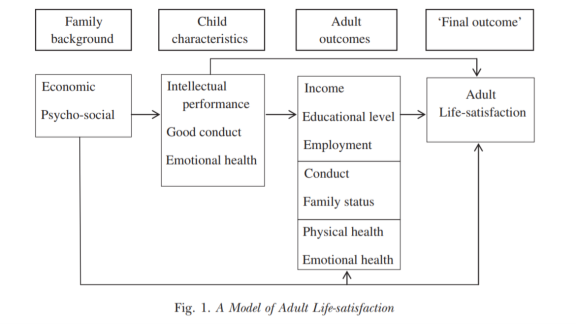

A Successful Life

While success is subjective and can be interpreted in many ways, such as obtaining a good job, having meaningful relationships and positively contributing to society, these are linked to the broader, enveloping term of ‘life-satisfaction’. The Perry Preschool project and the High/Scope Comparison study quantified life-satisfaction in terms of income, relationships and presence of a criminal record. To consider another perspective, which I feel gives a more in-depth account of factors contributing to liklihood of success, Layard et al. (2014) produced a model of indicators for predicting a fulfilling life (appendix 2).

“We show that the most powerful childhood predictor of adult life-satisfaction is the child’s emotional health, followed by the child’s conduct. The least powerful predictor is the child’s intellectual development.” (ibid. 2014, p. 1)

Paul Tough’s book, How Children Succeed; Grit, curiosity and the hidden power of character, emphasises the importance of character building and non-cognitive skills “we can’t get better at overcoming disappointment just by working harder at it for more hours” (2012, p. xv). Tough also explored why some children from high-income families with superior education available to them were outperformed by children from low-income backgrounds. The difference between them was not their IQ, but their differences in personality traits such as determination. Tough, like Layard, also recognised the impact of the family and culture as crucial during early childhood, and concluded “as much as possible, you protect him from serious trauma and chronic stress; then, even more important, you provide him with a secure, nurturing relationship with one parent, ideally two. That’s not the whole secret of success, but it is a big, big part of it” (p.182). Perseverance, curiosity, self-control and optimism. These are all character skills are described by Tough as vital for a successful life, yet they remain undervalued and overlooked by national curriculums. Character Lab Research Director, Andrew Sokatch, reinforces Tough’s argument when referring to the short-comings of curriculums, “science is suggesting to us we are missing half of what kids need to become fully engaged, successful, flourishing adults” (TEDx Talks 2014).

Also in support of this, Daniel Goleman has been championing the term Emotional Intelligence for over two decades, often referred to as EQ (1995). Goleman wrote a best seller based on his claim that non-cognitive skills were as important as IQ in the workplace and identified the core components as; self-awareness, self-regulation, internal motivation, empathy and social skills.

The research and case studies from Layard et al., Piaget and Tough all conclude that direct programme learning approaches are the least appropriate for early childhood education. To summarise, for Piaget, children need to be active learners, for Tough, children’s character and personality traits need to be nurtured to overcome day to day stressors as adults, and for Layard et al. their emotional needs and the family impact is the most important variable. The most outlying issue is the difficulty in obtaining quantitative results for EQ, due to disparity in construct, methodology and defining terms (non-cognitive, character, soft skills, and emotional intelligence).

Nonetheless, based on the determiners of success explored, it would be prudent to apply the High/Scope curriculum model to attempt to define the ideal classroom in an ideal school, whilst being conscious of the imitations of the study.

The Ideal Classroom

The classroom is where the teacher, the children and the environment assemble. There are two, very key points that needs to be kept in mind; those being the children’s cognitive and emotional development. Since the children need to learn though action to understand the circumstances under which things change or stay the same, the classroom should be set to enable this through a variety of materials. These materials should be provided with the freedom to explore, whilst the classroom remains to be a place where children can learn to understand and manage their own feelings and those of their peers.

According to Kress et al. (2005) there are messages and meanings being conveyed everywhere in the classroom; wall displays, classroom layout, teacher’s gesture, children’s gaze, and so on. Kress provides a full account of how meaning is made through multiple ways of examining discourse and that evaluating these aspects can reveal the weight of ‘power’ in the classroom. Whilst Kress raises important considerations, there is a danger of getting distracted by potentially negligible details and looking for meanings that are possibly interpreted in an overly subjective manner. The value of Kress’ work is making practitioners aware of the multiple modes and encouraging self-reflection, and reflection on the environment. Being a reflective teacher is beneficial to both the teacher and the children (Bracey 1987).

A Classroom in a Chinese Kindergarten

Similarly to America and the UK, many Chinese private kindergartens exist for profit. However, unlike in the west, private kindergartens in China tend to provide early education to children from low to mid-income families (Bu 2008, as cited in Li et al. 2016). Whilst public and private kindergartens both charge tuition, public schools receive significantly more subsidies from the government and generally have better facilities, resources and higher qualified teachers than private kindergartens (Hu and Li 2012, as cited in Li et al. 2016).

In a study researching the quality of early childhood education in China, across eleven provinces, it was identified that the majority of kindergartens use the direct instruction approach, “Most teacher-child interactions were one-way in a large-group manner and teachers paid little attention to children’s individual learning needs and interests” (Pan et al. 2010, cited in Li, et al. 2016).

A school adopting the proposed ideal approach as the aforementioned High/Scope curriculum would likely be faced with resistance from teachers and parents. As revealed by Li et al, the biggest problem with providing high-quality education in rural areas was hiring and retaining quality teachers. In addition to this, on the question of reforms, one teacher said to Wong in an interview; “if the government inspected the schools, teachers would implement the reform. If not, things would go back to normal” (2018 p. 11). To exemplify this further, the Chinese educational bureau forbids teaching reading and writing skills in kindergartens, as they wish this to be taught by appointed government teachers in primary school. Nevertheless, the teaching of reading and writing continues to happen in every Chinese kindergarten I have worked for over the past seven years. In kindergartens across China, teachers maintain authoritative positions in the classroom and work towards pleasing the parents in terms of academic results and displays of ‘ability’ which in reality can consist of reciting learned scripts with no regard to the child’s core understanding.

According to Dave Lenin, co-founder of KIPP (Knowledge is Power Programme) the finding, hiring and retention of high-quality teachers and principals, being those that understand what the school is trying to achieve according to its core values and visions, are the most important success factor. “Great leaders are the hallmark of great schools” (Lenin 2012).

The second key barrier to implementing this change of approach would be attitudes of parents. Up until recently, China’s one-child policy put immense pressure on children to do well. As a result, families invest in their child’s future and ultimately their own futures as elderly persons who may rely almost solely on the financial support of their kin. Since tuition fees for kindergartens are expensive, some higher than college fees (Wang, 2009), parents expect results in terms of language acquisition and academics. From my own interactions in one-to-one parent meetings, the majority of parents’ primary concern is their child’s English skills, with comparatively less attention centred on their child’s characteristics, how they deal with challenges, or emotional intelligence. I find that parents’ perception of education is often based upon their own experiences, and an approach differing to their own, notably a High/Scope curriculum, almost certainly contrasts to the type of early education that they would have received, if any education at this level at all. It is very likely they would have been educated via direct instruction throughout childhood, and often only identify with this method as being correct. This situation can cause tension between the parents’ and the school’s values, resulting in a ‘values drift’ (Gewirtz and Cribb 2009) as the school is inclined to satisfy the parents funding the school. It can also be attributed to tradition. According to Wang, Chinese epistemological traditions are based on ancient beliefs such as Confucian and Taoist educational thoughts (2004 cited in Fu, 2018). During this time of globalisation, China is faced with the juxtaposition of valuing both deep-rooted, cultural beliefs and rapid modernisation.

Conclusion

Having reviewed various curriculum approaches, the High/Scope model was identified as being best placed to support the idea of an ideal classroom in an ideal school. On the basis that the ideal school would essentially set up its attendees for a successful life, this model does not put the emphasis on high academic achievement. Instead, it fosters cognitive development and emotional health in an open and secure environment, where the teacher is not the paradigm of control.

It still remains that the Direct Instruction approach is the most inappropriate for early years education and that teachers should not be unquestionable authoritative figures, rule-makers and knowers-of-all, but a reflective person who facilitates tangible activities, real things to see and do, works together with others and a embodies a model of emotional intelligence.

Indicators of a successful life place intelligence in third place after emotional health and conduct (Layard, et al. 2014), making emotional intelligence a key factor in being successful. When applying this model in China, a country experiencing never before seen levels of depression, the evidence from this study supports how an emotional intelligence approach could offer a possible solution to the future emotional health of generations.

Having identified a lack of emotional development in most Chinese kindergartens and a leniency towards formal Direct Instruction, the findings of the High/Scope comparison study suggests that this could in fact be damaging for the children’s well-being and a shift in curriculum perspectives in kindergartens would allow children to focus on developing their cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Various factors can account for why this continues to be the case, such as traditional values, and the ease of providing a system that can be assessed, versus the High/scope curriculum that lacks an identified system of evaluation.

A shift from a results-based approach could also be expected to face stern resistance, notably from parents. This could be countered by offering evidence to show that success in academics is not a reliable indicator of success in adulthood. This could carry additional weight when there is evidence as to how such an education could be crucial at the most important time of emotional development; early childhood education as displayed by the Perry Preschool Project.

References

- Al Jazeera English (2014) Depression stalks millions in modern China . Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3d2fIf6NAGQ [accessed: 7 January 2019].

- Becker, D. and Birkelbach, K. (2011). Teachers’ evaluations and the definition of the situation in the classroom. St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis [online]. Available at: http://ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/docview/1698178971?accountid=8018 [accessed: 8 December 2018].

- Barnard, R. (1998). Classroom observation: Some ethical implications. Modern English Teacher, 7(4), pp. 49-55 [online]. Available at: https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/871 [accessed: 12 January 2019].

- Bottery, M. (1990) Values behind the practice. The morality of the school: The theory and practice of values in education, pp.6-16 [online]. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=values+behind+the+practice+bottery&btnG= [accessed: 9 December 2018].

Bracey, G. (1987) Reflective Teachers. The Phi Delta Kappan, 69 (3), pp. 233-234 [online]. Available at: https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/stable/20403584?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents [accessed: 5 January 2018].

Bruner, J. (2009) The Process of Education, Harvard University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 163-174 [online]. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nottingham/detail.action?docID=3300117 [accessed: 8 December 2018].

EDCHAT (2012) Teachers TV- How Do They Do It In Sweden? . Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FofjbSdsgq4 [accessed: 2 December 2018].

Elkind, D. (1968).Giant in the nursery – Jean Piaget. New York Times26th May [online]. Available at: http://ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/docview/118265693?accountid=8018 [accessed: 28 December 2018].

Fu, G. (2018). The knowledge-based versus student-centred debate on quality education: Controversy in China’s curriculum reform. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, pp. 1-18 [online]. Available at: https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/doi/citedby/10.1080/03057925.2018.1523002?scroll=top&needAccess=true [accessed: 5 January 2019].

- Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the oppressed. Race and Secondary Education Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 163-174 [online]. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25595010?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [accessed: 8 December 2018].

Layard, R., Clark, A., Cornaglia, F., Powdthavee, N., andVernoit, J. (2014). What Predicts a Successful Life? A Life‐course Model of Well‐being. Economic Journal, 124(580), pp. F720-F738 [online]. Available at: https://nusearch.nottingham.ac.uk/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_wj10.1111/ecoj.12170&context=PC&vid=44NOTUK&search_scope=44NOTUK_COMPLETE&tab=44notuk_complete&lang=en_US [accessed: 15 December 2018].

Li, K., Pan, L., Hu, B., Burchinal, M., De Marco, A., Fan, X., and Qin, J. (2016). Early childhood education quality and child outcomes in China: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 427-438 [online]. Available at: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0885200616300096 [accessed: 30 December 2018].

Luster, T., McAdoo, H. (1995) Family and Child Influences on Educational Attainment: A Secondary Analysis of the High/Scope Perry Preschool Data Department of Family and Child Ecology, Michigan State University [online]. Available at: https://ovidsp-tx-ovid-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/sp-3.32.0a/ovidweb.cgi?WebLinkFrameset=1&S=NLMIFPPEBBDDGNGGNCDKHHIBLKNEAA00&returnUrl=ovidweb.cgi%3f%26Complete%2bReference%3dS.sh.24%257c1%257c1%26FORMAT%3dcitationFormatPrint%26FIELDS%3dFORMATl%26S%3dNLMIFPPEBBDDGNGGNCDKHHIBLKNEAA00&directlink=https%3a%2f%2fovidsp.tx.ovid.com%2fovftpdfs%2fFPDDNCIBHHGGBB00%2ffs046%2fovft%2flive%2fgv025%2f00063061%2f00063061-199601000-00003.pdf&filename=Family+and+Child+Influences+on+Educational+Attainment%3a+A+Secondary+Analysis+of+the+High%2fScope+Perry+Preschool+Data.&navigation_links=NavLinks.S.sh.24.1&PDFIdLinkField=%2ffs046%2fovft%2flive%2fgv025%2f00063061%2f00063061-199601000-00003&link_from=S.sh.24%7c1&pdf_key=B&pdf_index=S.sh.24&D=ovft [accessed: 20 December 2018].

Ryder, A., Sun, J., Zhu, X., Yao, S. and Chentsova-Dutton, Y. (2012) Depression in China: Integrating Developmental Psychopathology and Cultural-Clinical Psychology, Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41:5, 682-694, [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.710163 [accessed: 15 December 2018].

- Seligman, M., Ernst, R., Gillham, J., Reivich, K. andLinkins, M. (2009) Positive education: positive psychology and classroom interventions, Oxford Review of Education, 35:3, 293-311, [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934563 [accessed: 12 December 2018].

Schweinhart, L. and Weikart, D. (1997) The High/Scope Preschool Curriculum Comparison Study through Age 23. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 12(2), 117-43 [online]. Available at:https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0885200697900090 [accessed 20 December 2018].

TEDx Talks (2014) Teaching character – the other half of the picture, Sokatch, A. . Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxHGSTV3LF0 [accessed 12 December 2018].

Upstart Scotland (2015) High/Scope Preschool Curriculum Comparison Study . Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BlfJMFtHjbw [accessed 20 December 2018].

- Walker, S., Wachs, T., Grantham-McGregor, S., Black, M., Nelson, C., Huffman, S., Richter, L. (2011). Inequality in early childhood: Risk and protective factors for early child development. The Lancet, Volume 378, pp. 1335 [online]. Available at https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.nottingham.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0140673611605552 [accessed 2 December 2018].

Wang, H. (2009) Young parents struggle with kindergarten fees, ChinaDaily.com.cn [online]. Available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2009-07/15/content_8429809.htm [accessed 16 December 2018].

Appendices

Appendix 1:

Curriculum by Gender Analyses of Outcomes Differing Significantly by Curriculum Group. Schweinhart, L. and Weikart, D. (1997) The High/Scope Preschool Curriculum Comparison Study through Age 23. pp. 136-137.

Appendix 2:

A Model of Adult Life-satisfaction. Layard, R., Clark, A., Cornaglia, F., Powdthavee, N., and Vernoit, J. (2014). What Predicts a Successful Life? A Life‐course Model of Well‐being, ppF271.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal