Relationship Between Aggression and Violent Offending

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Criminology |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3645 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

What is the relationship between aggression and violent offending?

Introduction

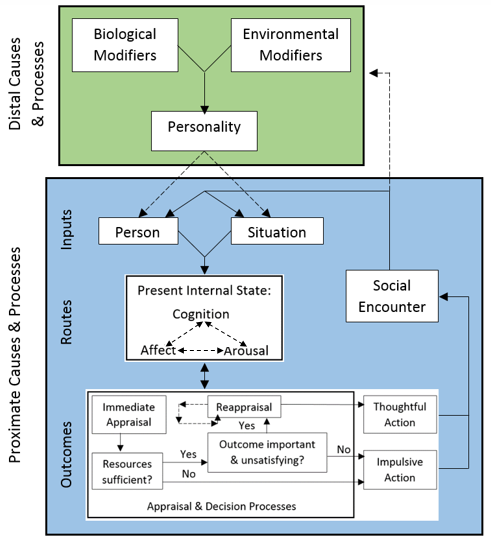

Aggression may be associated with violent crimes as homicide and rape, the meaning of this term deserves a much more extensive description and is in general a difficult concept to define. Whereas aggression is referring to causing harm, injury and destruction to another, this behaviour is also seen as a necessary adaptive device or an emergency mechanism (e.g., self-protection). It has several subtypes and degrees that eventually flow into each other and has thin lines to cross, between being positively or negatively used. “Violence sometime has been treated differently from aggression by criminologists, political scientists, public policy makers and the general public, whereas social psychologist see it as a subset of aggression” (Warburton & Craig, 2015). This causes ambiguity while reading researches or speaking to one another and therefor needs to be clarified. In order to gain a stronger understanding of these concepts, an attempt has been made to explain aggression, violence and violent offending differently. Causes of aggression and factors that may influence this behaviour are described through the most used and comprehensive theory which fits these concepts; the General Aggression Model (GAM), presented in figure 1. A theory that is commonly used and is a bundle of half a century research and philosophy. Each stage of the model has been looked into in order to make theoretical explanations or presumptions made by others or the writer himself. In the conclusion, we described what the possible outcomes could be of the factors that influence aggression negatively or positively. Throughout this paper the terms “aggression” and “aggressive behaviour”, as well as “violent offending” and “violent crimes”, are used interchangeably.

Aggression and Violent Offending

Warburton & Craig (2015) argued that there are three key issues which are important to understand while defining human aggression. Firstly, researchers have used different clarifications and meanings what has resulted in definitions of aggressive behaviour that are hard to compare. One of the most common definitions found is by Bushman & Huesmann (2010), two leading professors in the field of Social Psychology. They stated that “aggression is any behaviour enacted with the intention to harm another person who is motivated to avoid that harm.” They suggested that a good addition to this definition would be that there is no free will included by the person who is being harmed. This will exclude any (sexual) deviate behaviour where there is a thrive to feel a certain level of pain, such as body suspension.

Secondly, aggression is interchangeably used with related concepts such as anger, hostility and competitiveness. It is important to understand that aggression is referring to an emotional state. “Attitudes like wishing the worst for another, and motivations such as the desire to win or control one’s environment may contribute to a person behaving aggressively but are not aggression per se” (Warburton & Craig, 2015). For example, a football coach who is coaching his players to play aggressively, is not instructing to harm other players. He is trying to get his team to operate on the thin line between playing hard but fair versus really aggressive and harmful. The term aggression is often in theory misused to contemplate a mindset. If the behaviour is applied correctly, fair play, then this could be seen as positive aggression. On the other hand, Richard (2009) claimed that some acts of violence are not criminal or even deviant. For example, violence in self-defence, violence by social control agents and violence in war are typically neither criminal nor deviant. Punishment made by police, parents of sometime teachers can be seen as appropriate. Needless to say, this is only allowed if people think the punishment is fitting the deviant behaviour. Striking is, when the punishment isn’t hard enough we condemn them that they are too lenient. They will be criticized if the wrong-doer will get away with it. Applied aggression seems a moral necessary.

Thirdly, violence is interchangeably used with the term aggression. Misapplying this concept is causing again miscommunication and confusion among all disciplines.

A frequently found definition by Warburton & Craig (2015) states that “violence is aggression that is intended to cause harm extreme enough to require medical attention or to cause death.” Therefore, all violent behaviour could be labelled as aggression. Besides, nonphysical forms of aggression have earned the label ‘violence’ when the consequences are severe enough, “usually when directed at children or intimate partners with the goal of severely harming the target’s emotional or social well-being” (Allen & Anderson, 2017). These recent statements demonstrate that there is a shift in labelling aggression. The believe in a broader perception of the term aggression will cause even more ambiguity. Therefore, if this trend will continue most definitions need to be reviewed. A clarifying addition to the definition by Warburton & Craig (2015) of aggression is that medical treatment could be described as both physical and psychological. As one of the few, The World Health Organization [WHO] (2014) does include emotional violence in their definition. They describe it as, “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.” This definition provides a broader view in which violence can occur, describes three forms in which it can be feasible and in addition to that, it includes the results of violent behaviour. In their article regarding violence “A global public health problem” (WHO, 2014) they argued, that the nature of violent behaviour can be physical, sexual, psychological or involve deprivation or neglect. What WHO does not include but is occasionally found in the literature, is that damaging objects can be classified as violence. Allen & Anderson (2017) claimed that, “attacks on inanimate objects are classified as violence (e.g., the burning of cars or homes and the destruction of property), but the concept of aggression is often limited to attacks on people”. Striking, is that New Zealand legislation has a Crimes Act 1961; 307A: Threats of harm to people or property. This crime act combines behaviour that results in creating risk to the health of one or more people, major property damage, major economic loss to one or more persons or major damage to the national economy of New Zealand. Taking that into account, for causing damage to objects you could be sentenced with a crime act that includes harming people. This is a significant contradiction to what most research is showing and seems morally incorrect. Most common definitions of violence behaviour that are found do not included property damage or economic loss. Moreover, if you put this to the test by asking a person if he could choose between being sentenced for damaging an object or harming a person, they will definitely choose damaging an object. Instead of damaging an object, harming a person will never be tolerated by our society and could have a major impact on our career and life. For that reason, this crime acts could lead to severe consequences for a person’s future by “only” damaging an object. This does not feel socially responsible and justifiable.

If we zoom in on violent offending, violent behaviour and violent offending are clearly overlapping domains. As we described, not all violent behaviour can be considered as criminal behaviour but all violent crimes include violent behaviour. Crime involves rule breaking, whereas violence involves intentional harm-doing using physical force (Richard, 2009). To clarify and distinguish, “aggressive and violent behaviours are best conceptualized as being on a continuum of severity with relatively minor acts of aggression (e.g., pushing) at the low end of the spectrum and violence (e.g., homicide) at the high end of the spectrum.” (Allen & Anderson, 2017). In addition, violent behaviour does not have to cause actual harm to be classified as violent. Attempting to shoot someone, but missing, is still considered a violent act. You could distinguish violent crimes in two forms, indirect or direct cause of harm. For example, theft and illicit drug use are crimes but do not directly evolve in violent behaviour. “Different types of crime involve different attitudes toward harm. Some offenders want to harm the victim (e.g., most assaults), some do not care (e.g., most robbery and property crimes).” (Felson, 2009). Controversial is that some studies of rape illustrate findings that the primary intent of some rapists is not to harm the victim but rather to gain sexual gratification. Therefore, theoretical it could be considered as an indirect cause of harm. However, there is certainly a direct cause of harm to the victim.

Through this brief summary we tried to explain aggression, violence and violent offending and their differences and similarities. But to gain even a stronger understanding of the relationship between aggression and violent offending, we need to understand which factors influence aggressive behaviour, directly or long-term. Therefore, a theory of aggression is needed to systematically deepen this relationship. Throughout the years multiple theories have developed to understand why aggressions is present in people. Some examples are: frustration–aggression theory (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939); socioecological models (Heise, 1998); cognitive neoassociation theory (e.g., Berkowitz, 1989); social learning theory (e.g., Bandura, 1973; Mischel & Shoda, 1995); script theory (e.g., Huesmann, 1986); excitation transfer theory (e.g., Zillmann, 1983) and social interaction theory (e.g., Tede- schi & Felson, 1994). (Bushman, DeWall & Anderson, 2011). These theories have given vital knowledge into the reasons why people behave aggressive. However, it is not giving a broad framework to understand aggression in different contexts. Therefore, the most important theories are combined which resulted in the GAM. Each episodic stage of the cycle of the GAM is examined with respect to the relationship of aggression and violent offending. Hypothetically, factors that negatively influence aggression presume directly that there is a greater likelihood that someone could behave aggressively and, therefore, may get involved in violent crimes. Positive factors suggest the opposite. Someone should more likely capable to control aggression and may not get involved in violent crimes. More important, each episode of aggression or non-aggression serves as a learning trial that can influence the development of aggressive knowledge structures and thereby personality over time. The GAM includes both distal causes and processes and proximate causes and processes. The distal causes and processes are the biological and environmental factors, which contribute to the personality of a person. They operate in the back of each cycle and are either developed through genes or learned by experiences (scripts). The proximate causes and processes have three important stages to understand the cycle of aggression. Person and situation inputs, present internal states (i.e., cognition, arousal, affect), and outcomes of appraisal and decision-making processes. A feedback loop can influence future cycles of aggression, which can produce a violence escalation cycle (Anderson, Buckley & Carnagey, 2008).

Firstly, we will start looking into the distal causes and processes. There are multiple biological factors that could increase the likelihood of aggression. One of these factors is testosterone which is positively related to aggression. Researches showed that there is correlation between higher levels of testosterone and physical aggression in boys (Scerebo & Kolko, 1994). Which suggest that girls, who have significant less testosterone, are less likely to behave in a physical aggressive manner. Next to that, there is an association between cortisol, our stress hormone, and externalizing behaviour such as aggression. (Van Goozen, Fairchild, Snoek & Harold, 2007). This suggests that a person who is only stressed but has violent behavioural scripts could be a direct danger for his environment. Other biological factors that can have a direct or indirect influence on aggressive behaviour are ADHD, low serotonin and low arousal. (Anderson, 2004).

Research demonstrated that environmental factors can increase the likelihood of developing aggression. “The first researches pointed to social inequality, poverty and the environment as the main reasons for the display of aggressive and criminal behavior.” (Buss & Okami, 1997). Which implies that the violent offending rate is lower in high social economic areas. Other early findings demonstrated that “consistent parental discipline increased positive parental involvement, and increased monitoring of the child’s activities are accompanied by significant reductions in a child’s antisocial behaviour.” (Farrington, 1978). Other important factors which could influence aggressive behaviour negatively are cultural norms supportive of violence, violent or group conflicts and chronic exposure to violent media (Anderson, 2004). A positive index of these factors would most likely result in a less aggressive outcome.

Secondly, we will start looking into the proximate causes and processes. Person factors are any individual differences that may influence how a person responds to a situation, e.g., characteristics with low self-esteem. A systematic review examined 19 studies, 12 of which were found low self-esteem to be related to violence (Walker & Bright, 2009). Presumably, low self-esteem could trigger anxiety, which in turn could resulted in a fight- or flight mode and could lead into aggression, e.g., used as a self-defence mechanism. Similar researches finding by Lee & Hankin (2009) argued that “negative emotions among people with low self-esteem, such as depression, anxiety, and anger may be predictive of aggression and violence”. (Lee & Hankin, 2009). Next to that, research showed that aggressive behavioural scripts, moral justification of violence, certain personality disorders, narcissism and low agreeableness could lead to an increase of aggressive behaviour (DeWall, Anderson & Bushman, 2012).

Situation factors are aspects of the situation that may influence whether aggression occurs. Many situation factors have been identified as an increasing factor for the likelihood of aggression. For example, data regarding heat and warm climate regions in de United States consistently showed that violent crime rates are higher than in colder regions (Anderson, 1989). Next to heat, alcohol could be a negative influencer with regards to violent behaviour, this is a regular known factor for most of us and a major problem for our society. A Canadian general population study found that alcohol was present in roughly 38% of incidents involving serious arguments, 57% of incidents involving threats, and 68% of incidents involving physical aggression (Wells, Graham, & West, 2000). Other common factors are social stress, social rejection, bad moods, frustration and the presence of weapons (Anderson & Carnagey 2004).

Person and situation factors can be influenced by a person’s affect, cognition or arousal. These three variable types make up a person’s present internal state and changes in these variables could have an effect on the likelihood of aggression.

For example, research shows that individuals with a low IQ may be less able to successfully negotiate social relationships and situations, which result in a greater likelihood of violent offending (Farrington & Welsh, 2008). Megreya (2015) showed that his study provides significant contributions to understand criminal behaviour. Large and strong deficits in EI were observed among offenders. Meaning, that a low EQ could have strong relations with violent offending. Furthermore, study towards arousal showed that men who are expressing minor sensitivity to their wives, were more likely to commit intimate partner violence compared to men who did. (Marshall & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2010).

The third stage of the proximate processes focuses on appraisal and decision processes, and on aggressive or nonaggressive outcomes. The person or group who appraises the situation will decide how to respond, the outcome of this action will influence the encounter, which again influences the person or group and situation factors. The episodic cycle will restart after this last stage. The violence escalation cycle is a good example of negative outcome of the third stage of the GAM. The violence escalation cycle demonstrates that retaliation, negative appraises and decision processes by the encounter person or group, could again trigger an aggressive outcome, which in turn could end in retaliation over retaliation by both sides. For example, a violence escalation cycle of two nations. Nation A tries to increase its power by invading a neighbouring country. Nation B, the neighbouring country, encounters this lack of respect of boundaries and a shoots one missile to show their strength but not to harm. Accidently, this missile kills a powerful person in nation A their government, who seems to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Nation B is in state of mourning and retaliate in their turn to show the world their suffering and strength. They strike and shoot a missile in the main capital which kills a large number of innocent civilians. Several other neighbouring countries choose their alliances and the situation quickly gets out of control. The cycle persists through several iterations of violent actions in which one nation perceives its retaliation appropriate and justified, whereas the second unit perceives it to be inappropriate and exaggerated.

Conclusion

Researches demonstrate that aggression, “any behaviour enacted with the intention to harm another person who is motivated to avoid that harm” (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010), is used as a broader concept of violence and violent offending. It describes a large number of behaviours that could be either negatively or positively used by a person or group. Violence is often described as a subcategory of aggression that is intended to cause harm extreme enough to require medical attention or to cause death (Warburton & Craig, 2015). On the other end of the spectrum, findings show that violence can be used appropriate if it fits the deviant behaviour (e.g. self-protective) or against objects. Predominantly, the more severe the aggressive behaviour is, the more likely it will be described as violent behaviour or violent criminal behaviour. But due to different interpretations and definitions of these concepts by e.g., criminologists, psychologists, political scientists and public policy makers, there is unclarity among these concepts.

Critically reviewing the relationship between aggression and violent offending showed that a person who is showing only minor aggression, could easily become violent influenced by the wrong conditions. Each stage of the GAM cycle showed that a broad spectrum of factors, through years or situational circumstances, can influence aggression majorly. Even a bad mood (Anderson & Carnagey 2004) could eventually lead into violent behaviour if this person has developed violent behavioural scripts throughout experiences in the past. An unequivocal answer why someone reacts aggressively eventually cannot be given but could partially tracked back by psychological researches using the GAM

Bibliography

-

Anderson, C.A. (1989). Temperature and aggression: Ubiquitous effect of heat on occurrence of human violence. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 74-96.

Anderson, C. A., Buckley, K. E., & Carnagey, N. L. (2008). Creating your own hostile environment: A laboratory examination of trait aggression and the violence escalation cycle. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 462-473.

Anderson, C.A., & Carnagey, N.L. (2004). Violent evil and the General Aggression Model. In: A. Miller (Ed.), Social Psychology of Good and Evil (pp. 168–192). New York: Guilford Publications. - Allen, J. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2017). Aggression and violence: Definitions and distinctions. In: P. Sturmey (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of violence and aggression (pp. 3-31). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley.

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning theory analysis. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration–aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 59-73.

- Bushman, B.J., DeWall, C.N. & Anderson, C.A. (2011). The General Aggression Model: Theoretical Extensions to Violence. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 245-258.

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2010). Aggression. In: S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 833-863). (5th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (1997). Human Aggression in Evolutionary Psychological Perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 605-619.

- DeWall, C. N., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2013). Aggression. In I. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of Psychology, 2nd Edition, Volume 5, 449-466. H. Tennen & J. Suls (Eds.), Personality and Social Psychology, New York: Wiley.

- Dollard, J., Miller, N. E., Doob, L. W., Mowrer, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Farrington, D.P. (1978). The family backgrounds of aggressive youths. In: Hersov LA, Berger M, Shaffer D (eds). Aggression and Antisocial Behavior in Childhood and Adolescence (pp. 73–93). Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press.

- Felson, R.B. (2009). “Violence, Crime, and Violent Crime.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 3(1), 23-39.

- Heise, L.L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4, 262-290.

- Huesmann, L. R. (1986). Psychological processes promoting the relation between exposure to media violence and aggressive behavior by the viewer. Journal of Social Issues, 42, 125-139.

- Lee, A., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Insecure attachment, dysfunctional attitudes, and low self-esteem predicting prospective symptoms of depression and anxiety during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38, 219-231.

- Marshall, A. D., & Holtzworth-Munroe, A. (2010). Recognition of wives’ emotional expressions: A mechanism in the relationship between psychopathology and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 21-30.

- Megreya, A.M. (2015). Emotional Intelligence and Criminal Behavior, Journal Forensic Science, 60.

-

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102, 246–268.

Scerebo, A., & Kolko, D. (1994) Salivary testosterone and cortisol in disruptive children: Relationship to aggressive, hyperactive, and internalizing behaviors. Journal of the American Academic Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 1174-1184. - Van Goozen, S.H.M., Fairchild, G., Snoek, H., & Harold, G.T. (2007). The evidence for a neurobiological model of childhood antisocial behaviour. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 149-182.

- Walker, J., Bright, J. (2009). False inflated self-esteem and violence: A systematic review and cognitive model. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20, 1-32.

- Warburton, W. A., & Anderson, C. A. (2015). Aggression, Social psychology of. In: J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 373-380). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- WHO Global Consultation on Violence and Health (1996). Violence: a public health priority. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Wells, S., Graham, K., & West, P. (2000). Alcohol-related aggression in the general population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61, 626 – 632.

- Zillmann, D. (1983). Arousal and aggression. In: R. Geen & E. Donnerstein (Eds.), Aggression: Theoretical and empirical reviews (vol. 1, pp. 75-102). New York: Academic Press.

Figure 1. The General Aggression Model (GAM)

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal