Ipplepen Project Excavation Analysis

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Archaeology |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3219 words | ✅ Published: 23 Sep 2019 |

IPPLEPEN FIELDSCHOOL REPORT

AN OVERVIEW AND DISCUSSION OF EXCAVATION IN IPPLEPEN 2018

Table of Contents

Romano-British History of South West Devon

Post Roman History of South West Devon

Introduction

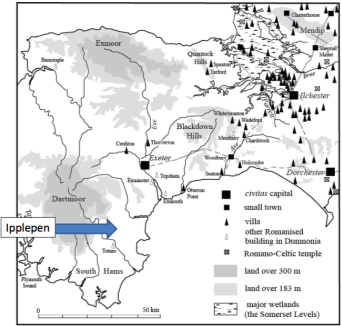

Ipplepen is a site located near Newton Abbot in the South West county of Devon.

Throughout excavations from 2007-2018 Ipplepen has emerged as a site rich with history, dating from late prehistoric, Romano-British and early medieval time periods. For the particular site in the summer of 2018, funded by the Heritage Lotter Fund the excavations are hoped to be those of a Romano-British and possibly post Roman settlement.

Aims

Overall, the aims of the Ipplepen project from 2007-present has been to understand the character of the site of Ipplepen and the context of the large and unusual assemblage of metalwork that has been reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme throughout the years. As well as this, Ipplepen is ideal to use as a case study of how late prehistoric, Romano-British and early medieval communities exploited the Devon landscape. Specifically, there’s interest in the relationship between this area and the Roman communities in South-West England. Ipplepen can be used to understand the origins of today’s historic landscape by using the existing patters of fields, roads and settlements and comparing them to the historic finds of the excavations.

This season, the aim is to explore areas of the site that were not previously examined. Chosen based on the location of geophysical anomalies, the site’s goal is to locate the Romano-British and possibly the post-Roman settlement that was present in the area at the time.

With utmost importance, this season continues the long standing work with community and public engagement. Working with volunteers, students and the local community is aimed at educating and enriching the local culture and education, and culminates with a community open day that reaches further than just the local community and is open to all.

Context

As stated in the aims, the goal of the excavation is to locate evidence of a Romano-British settlement and possible post-Roman settlement based off of the geophysical surveys. Britain as a whole has a rich history linked to Romano-British settlements and post-Roman settlements.

Iron Age Settlements in Britain

The area of South West Britain where the excavation occurred was occupied by the Dumnonii. In settlement terms this area was inhabited by farmers or stockbreeders on fortified hil-top or hill slope villages. Mainly in settlements of an enclosed agricultural homestead called a round (Thomas, 1966). Non hillfort settlements in the Iron Age appear to be characterized by long continuity and stability in contrast to hillforts and their major changes of form (Collis, 1966).

Romano-British History of South West Devon

In AD 43 when Emperor Claudius and his government invaded southern Britian the Roman’s were interested in the resources and metal wealth in England. The relationship between the Romans and the Dumnonii is difficult to archaeologically confirm (Thomas, 1966). There is no real evidence that the South West’s incorporation into roman Britain was marked by strife that can beassociated with the neighbouring areas (Thomas, 1966). Rural settlement in the south-west of England during the Roman period is argued in large part to be a product of the local Late Iron Age settlements rather than of Roman influence. This is due to the lack of evidence of large Roman establishments, the nearest single town to Ipplepen being the civitas capital of Isca Dumnoniorum, known today as Exeter. It seems that the task of the military in Exeter was the annexation of the Dumnonian peninsula, due to the tin deposits. No evidence has been found that suggests that the site of Exeter was occupied when the Roman military arrived. Although evidence suggests a sparsely settled landscape in the South West, there is palaeo-environmental evidence that indicates that the area was largely cleared of woodland by the Iron Age and remained this way throughout the Roman period (Rippon, 2018). The rural settlements in this area were associated with ditched field systems of the type found in lowland Roman Britain. The scarcity of Romano-British field systems is interesting due to the face that there is evidence of planned landscapes from the Middle Bronze Ages in lowland areas (Rippon, 2018). Evidence suggests that most people in the countryside were living in a style which had its roots deep in prehistoric society, and these settlements endured into the post-Roman period (Pearce, 1978).

Post Roman History of South West Devon

In the mid 4th century to approximately the 12th century, Christian establishments were assimilating into the composition of the British land. The Roman Army had departed from Britain by the 4th Century. In the 4th century Britain was reorganised as a ‘diocese’ with military forces under the command of the Duke of the Britains (English Heritage, 2018).

Features and Date Ranges

The features that are usually found in the project area are boundaries, tracks, enclosures, roundhouse. Finds that have been uncovered in this area also include material culture such as ceramics, building materials, metal finds and coins. Not all of the material culture found originates from the South Devon area but these finds are not unusual. The features and material culture that have been excavated come from the Bronze Age, Iron Age, Romano-British settlements and post Roman settlements.

Relationship to Nearby Sites

Relevant sites to the 2018 excavation in Ipplepen are those of Denbury, Milber and the Roman Roads that are found in Devon.

- Milber Down Hillfort is a multivallate hillfort, and when excavated was found to have evidence of Iron Age occupation and Romano-British activity to the South-East.

- Denbury Hill Fort has two close set ramparts and a deep ditch on the east and south sides, the fort was built around 300-100BC. There are Bronze age barrows inside that were built earlier than the fort itself. Although there are no excavations Early forms of the place name ‘Defnasburh’ and ‘Deveneberie’ meaning ‘Fort of the Devon People’ suggest it was an important place inhabited in post-Roman times as well as in the Iron Age.

- Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum) is one of the closest large Roman city to the site of Ipplepen. Roman roads have been traces as far as Teign. Another small road has been traced outside of Newton Abbot.

These nearby sites are relative to the Ipplepen project because they are evidence of the continuity of occupation of the south west Devon area from the Iron Age to Roman periods. Denbury also links the area to earlier prehistoric features.

Through the excavation, questions will be answered, such as, to what extent is there continuity of occupation from the Romano-British period to post-Roman periods? Through the discovery of material culture and features such as ditches can we relate the site to the record of the wider area and relative nearby sites?

Methods & Results

In brief, the method in which the excavation took place is as follows. The machine opens and backfills trenches. This season’s trenches are numbered TR16 and TR17. The team then verticalises and cleans, trench edges. Once this is done the next task is to shovel out loose soil from base of trench. Next, a planning grid is set and the base of the trench is cleaned using trowels to expose the surface without having any deep furrows holes or bumps that could misguide interpretations of features. Features are given context numbers and the pre excavation plan is started. Excavation plan determined by supervisors was to excavate several features at once. This included the circular anomalies, ditches and post holes. Earliest contexts were excavated first and then the later ones. For some bulk samples were take to see if there were any charred plant remains. Then record of a feature is done once the excavation is complete. Dry sieving was utilized in important features such as the well and in certain parts of the ditches. As well as, finds washing and processing for all the materials found within the trenches.

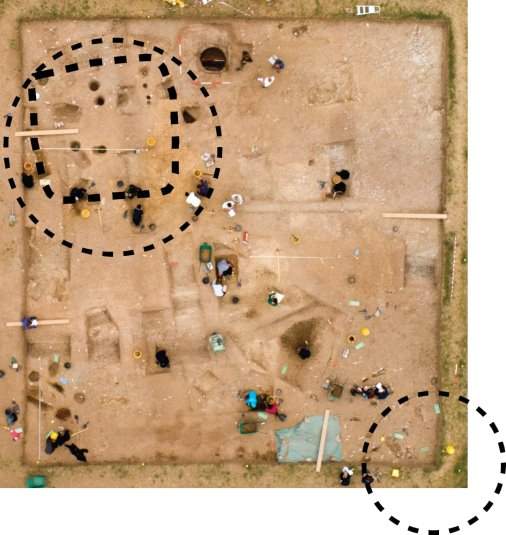

Based off of the geophysical surveys there were interesting anomalies that were the deciding factor in where to place trenches in 2018. Trench 16 and Trench 17 were then excavated and these excavations revealed features and material culture that was quite complex.

Trench 16

(Thomas, 1966) (Collis, 1966)Features

The features that are mentioned in this report are those that provided insight into the occupation of that settlement. Furthermore, the relationship between each of the features is important to distinguish to help theorize the use of the site in different time periods.

Most distinguishable in the photo are the two round houses in the south east corner and south west corner of the trench. Inside the largest roundhouse is a rectangular feature. This feature does not cut the roundhouse and thus, it is debatable as to what it could be.

The main well was found in the eastern most side of the trench and contained hordes of material culture. There was also a smaller well located slightly to the south east of the main well. The largest well cuts the feature of the round house and thus is more contemporary than the roundhouse in the south east corner.

On the south side of the trench two ditches were excavated that run parallel to each other. On the north east side of the trench another ditch was excavated and it became visible that this ditch curved around to create a boundary around the north east round house.

Post holes were found throughout the site, mainly within the largest round house and near the hearth. The post holes near the hearths could have potentially been for a structure that was needed in relativity to the hearths. The post holes in the round house could relate to either the roundhouse or the rectangular structure, the depth and way they are position could potentially indicate the presence of a shrine or perhaps as part of the structure of the rectangular or roundhouse features.

The hearth in the south western corner indicates the presence of smelting or metal working.

Throughout the excavation material culture contributed to the understanding and dating of different areas of the excavation.

Pottery/Ceramics

Notably, a lot of Late Romano-British Pottery was recovered from Trench 16. Specifically, black burnished ware. Black burnished ware was produced at a series of sites scattered around the shores of Poole Harbor, they came in forms of simple pots, some with a body zone of lattice decoration (Pearce, 1978, 35-36). The sherds found on site did have some evidence of lattice decoration. Production of black burnished water came to an end at the beginning of the 5th century, but the pots themselves could have been used and distributed for longer (Pearce, 1978, 36).

A significant find was that of Roman roof tiles, what this means is that there was definite Roman occupation at the site. Combine with the finds of slate roof tiles this shows a continued occupation from Iron Age to the Romano-British period and could perhaps suggest a cultural change in the settlement due to Roman occupation.

Large pieces of amphora were also recovered from the site. These were found in the North Eastern ditch where the Roman tile was found their presence indicates that wares that had been made outside of England had reached this settlement and indicates interactions with the larger part of the Roman Empire.

Metal Work

The coins found at the site dated from 2nd 3rd and 4th century they were found around various contexts in the site the date range and location of these finds suggest that the site was continually occupied and the coins were not just dumped. Although the amount of finds for coins in the far south west was lower than the rest of Britain, the percentage of 4th century coins against the totals know suggest that the countryside west of Exeter was receiving fewer coins than before from the mid-fourth century onwards (Pearce, 1978, 40).

Found in the south east corner of the trench was burnt clay soil, indicating the presence of a hearth. Several copper smelting chunks were found throughout the site, notably in the ditches near the hearth. Pearce suggests that there isn’t evidence of fine worked metal in the South West. However, found in the south eastern most ditch was a metal bracelet. This find specifically helps develop a picture of cultural practices from the time and provides evidence that there could have been fine metal work. Also in the trench was a brooch, some sites in south west Britain produced early brooches and were recovered from Iron Age burials which suggests that at least certain members of society wore brooches pre-conquest (Smith et al. 2018, 41-44). Rural population wore clothes that didn’t often require the use of brooches to fasten them. The rare recovery of adornments from rural sites suggests that native populations couldn’t acquire material in a tightly controlled military landscape (Smith et al. 2018, 41-44).

Furthermore, a stylus was found in the well, this stylus is an indication of communication which is one of the most significant finds. People in urban and military sites spoke Latin and could read and write the language. Spatulae or styli mainly of iron or copper alloy were used to write (Smith et al. 2018, 69). This stylus would have meant that there was correspondence with bigger Roman cities in Britain or even communication with the wider Roman empire. It gives evidence that although evidence of occupation in the South West is considered sparse, the settlements were not necessarily on the edge of the empire and rather could have been occupied at some point by the military.

Another important find was clusters of hobnails, they were found in the eastern ditches in several locations. These hobnails came from Roman military shoes, although the presence in the ditch indicates that they were thrown away, it still suggests that there was military occupation within the settlement.

Skeletal Remains

Animal Bones were found frequently in Trench 16, probably of most importance was the sheep, cattle and horse bones.

Butchery marks on bones found in ditch indicate that there was agricultural practices and use of animals for meat. Rural life would have encapsulated a wide range of activities the primary goal of which would have been to provide food (Smith et al. 2018, 78-79). Changing patterns of land tenure after the roman conquest would have had significant affect on agriculture and livestock (Smith et al. 2018, 78-79). With the suggested military presence from the hobnails and the high quantity of cattle bones found, agriculture and livestock output would have been necessary to support the military.

Trench 17

Features

The features discovered in Trench 17 were 21 Romano-British graves, only 2 were excavated. The graves are either late roman or post roman in date because they are not cremations in postholes and rather are inhumations, although the acidity of the soil damaged the bones. Small rural settlements blur the boundary between larger, separate formal cemeteries and more integrated burials within and around the settlement they would seem to have been deliberately placed in specific burial zone but lie at the edges of a nucleated settlement (Smith et al. 2018, 231). The presence of these graves close to Trench 16 could potentially link both the trenches together.

A linear feature on the North side of the trench is thought to be a medieval trackway, the linear ditch on the South side of the trench is suggested o predate the graves and is prehistoric.

Also found in Trench 17 was an Iron Age roundhouse.

Both Trench 16 and 17 show evidence of continual occupation or human activity from the Iron Age to the Roman period and in Trench 17 this time period even extends to the Medieval time period.

Public Engagement

Volunteers

Volunteers

Engaging with the community is a key part of the Ipplepen Project that brings in people from lots of different backgrounds and different interest. Volunteers from the local area aided in the excavations and find processing throughout the 3 weeks of the dig.

School Engagement

As part of the community engagement, the team on site worked with two schools with kids aged 6-10 years old. As well as educating them about the site and about the culture of the time periods we were investigating, there were lots of activities to interest in archaeology. These included looking at finds and drawing them, sieving through the spoil heap to find important finds we missed, and clearing away the top layer of dirt in the trenches. By teaming up with the schools we were able to educate the local children about the history of their home, and develop and interest in the past and archaeology.

Community Open Day

With over 600 people visiting the site, on the 8th of September members of the public were invited to take tours of the excavated trenches and visit several stalls of educational value, including the finds tent where they could learn about the material culture and organic material found during the excavations. The Community Open day allowed the local community and members of the public around the area to learn more about the history of their home and provided a great educational opportunity for the younger generation. This was all a part of the Heritage Lottery Funding project “Understanding Landscapes” and was a huge success in opening a gateway to the past for the community.

Evaluation

The aims of excavation this year were to locate the Romano-British and possibly the post-Roman settlement that was present in the area at the time. As well as, the publicly engage the community with the project. Ultimately, the excavations in 2018 succeeded in it’s goals.

The excavations provided evidence of occupation from the Iron Age to Medieval Age and uncovered large amount of material culture that can be further analysed to understand the site better. Further analysis or soil samples and carbonized remains will help date specific contexts and confirm the theories of each of the features.

The work with the community was a huge success as many volunteers learned about the site and the time period throughout the excavation. Furthermore, children from the local schools were able to experience valuable educational activities that helped them understand the local history. Overall, with the community open day receiving over 600 people, the engagement and educational value of the Ipplepen Project surpassed the aims set out at the beginning.

Bibliography

- Collis, J., 1966. Hill-Forts, Enclosures and boundaries. In: J. Collis & T. Champion, eds. The Iron Age in Britain and Ireland: Recent Trends. Sheffield : J.R. Collis Publications, pp. 87-94.

-

English Heritage, 2018. English Heritage: Romans. [Online]

Available at: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/story-of-england/romans/

[Accessed 12 January 2019]. - Pearce, S., 1978. The Kingdom of Dumnonia. 1st Edition ed. Padstow: Lodenek Press.

- Rippon, S., 2018. Making Sense of A Historic Landscape. 1st Edition ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, A., Allen, M., Brindle, T. & Fulford, M., 2018. New Visions of the Countryside of Roman Britain: Life and Death in the Countryside of Roman Britain. 1st Edition ed. London: Society for Promotion of Roman Studies.

- Thomas, C., 1966. The Character and Origins of Roman Dumnonia. In: C. Thomas, ed. Rural Settlements in Britain. London: Council for British Archaeology, pp. 74-99.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal