Critical Approaches to the Archaeological Heritage

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Archaeology |

| ✅ Wordcount: 3206 words | ✅ Published: 03 Nov 2020 |

Introduction and Significance:

The Caddo people, also known as the Hasinai, at their peak circa A.D.1100, were the most highly developed prehistoric culture within the state of Texas. The area that is now Alto, Texas, was selected by Caddo Indians as a permanent settlement in A.D. 800 (Perttula, 1992). Geoarcheological evidence in the area shows that the alluvial prairie contained qualities that would benefit the foundation of a village and synchronous ceremonial grounds – good sandy loam that would sustain crops to provide abundant food resources. The surrounding forest provided numerous materials including a permanent water source of springs that flowed into the Neches River (Story, 1990). For approximately 500 years, the Caddo people dominated life in that area, creating economical and social ties with similar cultures via trade and a sophisticated system that was both ceremonial and political.

The Caddo Mounds site served as the southwestern-most ceremonial center for the mound builders, which included the Caddo people. The mound builders were a collection of cultures that constructed earthen mounds as a way to memorialise the dead (O’Connor, 1995). Artifact analysis of raw geologic materials, such as shell from the eastern Gulf Coast, and copper from the Great Lakes region, show trading was occurring in Central Texas and as far away as present-day Florida and Illinois (Gregory, 1986). The site flourished until the 13th century, when most archeologists agree the ruling class left after a loss of their regional influence, and trade groups became less reliant on their cultural center for religious and political matters. The Caddo culture that remained in the area lacked its sophistication and material wealth (Swanton, 1942). Caddo groups continued to live in the area through the 1830’s in their traditional homeland but Anglo-American colonisation efforts in the 1840’s saw all groups removed from the area and placed on the Brazos Indian Reservation in 1855, until the Caddo (1,050 people) were removed to Indian Territory, now western Oklahoma, in 1959 (Smith, 1994).

Assessment of Visitor Population and Site Objectives:

The Caddo Mounds site seeks to educate the public about the development and significance of the Caddo culture. While general enthusiasts traveling in or around East Texas are the most common visitors, this site also hosts various educational programs. Prior to the tornado on April 13, 2019, which ultimately shut the site down temporarily for reconstruction, an ongoing project was being completed by a Girl Scout troop in the area dealing with heritage, tracing descent, and social hierarchy. In Caddo culture, descent was traced through the maternal line, rather than the paternal as most research is done now. Similarities to American social classes were recognised within the Caddo cultures, as religious and political authority in Caddo society was kept within a hierarchy of positions in communities and groups. Due to the excessive amounts of backfill and dirt recovered from ongoing and past archeological excavations, volunteer opportunities are also available at the site, which gave visitors a chance to learn how artifacts are not only recovered but processed and prepared for curation as well. A phone interview with Rachel Galan, the Caddo Mounds assistant site supervisor, took place on October 24, 2019, and detailed much of the information in this document (Galan, 2019).

Site Layout:

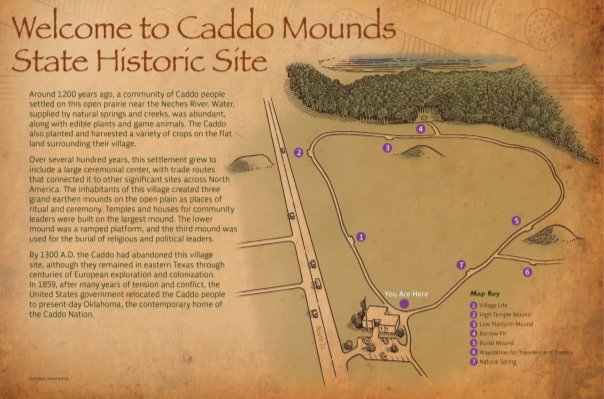

The Caddo Mounds site is a prehistoric ceremonial and occupational site that includes the mounds and a number of additional features (Figure 1). Visitors can walk a 0.7 mile (1.12 kilometer) self-guided tour, with an additional 0.4 mile (.64 kilometer) path that falls along the El Camino Real de los Tejas, mentioned in detail later. Tours, either guided or self-guided, typically take between 1.5 to 2 hours. Upon entering the visitors center, several exhibits are featured, which showcase artifacts recovered from the site (Figure 2) and detail the everyday life of the Caddo peoples, from their agricultural processes to their clothes and appearance (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Display in visitors center of the site overview.

Figure 2: One of the many exhibits in the visitors center detailing Caddo life.

Figure 3: A few of the artifacts on display in the visitors center.

After exiting the visitors center, the first stop along the tour is the village life area, which features a grass hut replica (Figure 4) complete with a shallow hearth (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Caddo grass hut replica outside of the visitors center.

Figure 5: Shallow hearth inside of the grass hut.

Following along the trail, the second stop is the High Temple Mound (Figure 6), which is the largest mound at the site and was used for ceremonial purposes. As this is the largest of the 3 mounds, a Texas Historical Marker plaque has been placed here (Figure 7), which commemorates the site as an area that effectively changed the course of Texas history.

Figure 6: Mound #1, the High Temple Mound.

Figure 7: The Texas Historical Survey Committee plaque at the High Temple Mound.

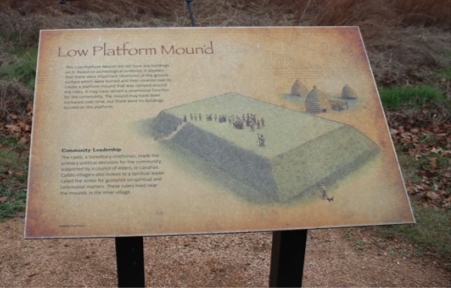

The third stop is the Low Platform Mound (Figures 8 & 9). This mound measures 175 feet (53.3 meters) north to south by 115 feet (35.1 meters) east to west. 1968 excavations of this mound produced evidence that this site was occupied from 800 A.D. to 1300 A.D. (Goolsby, 2010).

Figure 8: Mound #2, the Low Platform Mound.

Figure 9: Informational sign at the Low Platform Mound.

The fourth stop is the Borrow Pit (Figure 10), which is an area where dirt was removed to create the nearby mounds. From an outsiders view, it is apparent that the amount of man-power needed to construct these mounds was extensive and required well organised groups to complete such a task.

Figure 10: View of the Borrow Pit from the viewing platform.

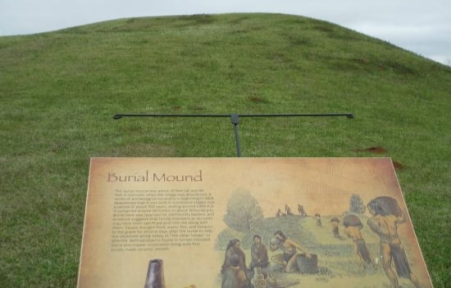

The fifth stop is the final mound, the Burial Mound (Figures 11 & 12), which was used as the ceremonial elite burial mound for the time the site was occupied. Archeological surveys have shown that the remains of approximately 90 Caddo Indians are buried here throughout six different levels (Goolsby, 2010).

Figure 11: Mound #3, the Burial Mound

Figure 12: Information sign at the Burial Mound.

The sixth stop branches out for a short distance into the El Camino Real de los Tejas (Figures 13 &14), which is a 2,500 mile (4023.4 kilometers) historic trail that was used by soldiers, settlers and missionaries to colonise the various communities of East Texas. The road became a means of change through migration, settlement, exploration, trade, and movement of livestock.

This trail connected numerous Spanish missions, posts, and presidios, from Los Adaes, the first capital of Spanish Tejas to Mexico City. This in turn linked many cultural and linguistic groups and promoted diffusion between the cultures as well as communication, and sometimes not for the best, biological exchange. While this meant new foods and agricultural practices were brought to the area, which helped with crop yields, production and processing, this also meant that new diseases were imposed on these areas, many of which were altogether unknown. Another problem with these routes is that they typically followed established trade routes and Indian trials, which cause irreversible impacts on the nearby populations.

A 17th century power struggle among England, France, and Spain to control North America is seen in the establishment of numerous presidios and missions along the camino real, indicating Spanish claim to the region. The camino real helped to settle the western and southern boundaries of the United States and Mexico. The road also provided passage for armies including those of the republic of Texas, the United States, Mexico, France, and Spain, for more than 150 years. During this time, thousands of American migrants came to Texas via the camino real, and it was their presence that led to the revolution against Mexico and ultimately to Texas independence and eventual statehood.

Use of El Camino Real de los Tejas promoted a blend of Mexican and Spanish traditions, cultures, and laws, resulting in a legacy and heritage that is still reflected in the landscapes, languages, names, music, and arts of Texas (National Park Service, 2018).

Figure 13: Informational sign about trade and traveling in the Caddo culture.

Figure 14: Sign located near the Caddo Mounds site.

The seventh and final stop on the site tour is an information board (Figure 15) about the natural spring located near the Caddo Mounds site, which was used by prehistoric people for numerous reasons. The spring feeds into the Neches River, and is one of the foundational reasons the Caddo settled in this area. This spring was used for cooking, drinking, washing, food preparation, and as an element in many construction processes, ranging from ceramics to structures. Pottery making in the Caddo culture is still continued by artisans today.

Figure 15: Informational sign about the nearby natural spring.

Site Constraints and Management Strategy:

On April 13th, 2019, a tornado swept through the communities of Weeping Mary and Alto, Texas, wreaking havoc at the Caddo Mounds site. Since then, the site has been closed, undergoing reconstruction after the visitor’s center and replica grass hut were destroyed. Several priceless artifacts in the exhibits were harmed and broken beyond repair. This natural disaster perfectly demonstrates a huge problem in the processes of preservation as well as conservation. The site is effectively being rebuilt and plans to reopen the site as early as February of 2020 are in place.

According to Rachel Galan, the site, being funded mostly by private donors, such as the recently founded Caddo Mounds State Historic Site Friends Association, which has raised $16,000 for reconstruction efforts (The Summerlee Foundation, 2019) as well as a visitor’s entrance fee ($4 per person, $3 per student ages 6-18, ages 5 and under get in free), has no financial issues aside from when archeological excavations are occurring on the area, which Rachel states are “embarrassingly underfunded”. However, volunteer work under the supervision of a formally trained archeologist helps with this, and since the site was forced to shut down, this has not been a problem to take into account. When it was open, an estimated 300 people a month, on average, would travel through the site, sometimes the summer seasons would see more visitors on account of larger educational groups, such as the aforementioned Boy and Girl Scouts of America. In regard to long-term preservation and conservation, any site within the state of Texas that is considered a Texas Historical Commission property and is therefore not in any danger of being demolished or uprooted in any sense. This applies to the Caddo Mounds site. (Texas Historical Commission, 2017).

In 1970 the area was designated as a site by the The Texas Historical Survey Committee, and in 1974 the area that the Caddo Mounds site is now located was established as a historic park. In 1981 another 23 acres was added, which include areas like the nearby natural spring and areas that were uncovered by associated archeological excavations, such as nearby occupation foundations and processing centers at which prolific amounts of lithics and preserved organic materials were found. It was at this time that the Caddo Mounds site was founded and an interpretive visitors center, complete with museum-characteristic exhibits was built, showcasing artifacts excavated at the sites. At this time the site only consisted of the visitor’s center, the 3 mounds, and knowledge of the borrow pit and nearby spring that was used, although it was not made a part of the tour until 2008 when the property was purchased by the Texas Historical Commission. The tour was later expanded to include the grass hut replica, borrow pit and viewing platform, nearby natural spring, and the short stent along the El Camino Real de los Tejas. Similarly, the Texas Historical Commission also purchased the nearby Indian Mound Nursery site in 2010, formerly owned by the Texas Forest Service. This property is adjacent to the Caddo Mounds site and is a densely forested area where many resources were foraged. The addition of this property expanded the overall Caddo Mounds site from 93 acres to 397 acres, which is all protected through state ownership (Goolsby, 2011).

Funding for the Texas Historical Commission comes from grants and fundraising. As of 2019, there are 46 different foundations, organisations and funders that are listed as the source of approximately 92% of their funding, the other 8% coming from singular donations, usually made online (Texas Historical Commission, 2019).

Qualitative Evaulation:

During the phone interview with Rachel, it was learned that during the tornado, Rachel’s husband Victor, who is the site president as well as lead archeologist, was critically injured. He sustained serious injuries to his neck and spine, and his recovery, though successful so far, still will be difficult. This led to the discovery of Rachel’s online blog, and the excerpt below:

“This morning, I started thinking about my own Sha-ho (Caddo word for one who experiences a tornado) story, thoughts triggered by songs and the telling of your memoirs. I read somewhere Jeff (Victor’s longtime friend and colleague) refer to Sha-ho as “he”. This struck me, because from my first thoughts about my experience, I knew Sha-ho as “she”. In her forceful, circular winds, she has given me a crash course in all it means to be a woman, Maiden – Mother- Crone. The very essence of Sha-ho is the ancient spiral of those feminine roles.

“Her fierceness cleansed ancient land and our lives and returned us to a time of awakening, a time of beginnings. In her wake, I’m mother striving to nurture my family and friends while allowing others to nurture me. In her wrath, I’ve embraced another of the ancient roles of women. I’ve made peace with giving death. I’ve given death to old ideas and beliefs. I’ve stood by my husbands’ bedside and given him permission to go if that was what he needed to do. I’ve been struck by the variety in what we experienced. As terrible as it was to see my husband so critically wounded, the pain in the eyes of my community, and the destruction of the site, I was oddly sheltered first by the building itself and then by my complete focus on keeping Victor breathing and conscious. I heard the work going on all around me, all the brave souls pulling people out of rubble and triaging the injured. I heard all that activity, but I didn’t see it. All I saw was Victor. I am thankful for the people who sat with us, gave us strength, and made sure I knew that we were not alone. Life flight came and ended that chapter. We are still in the second chapter of Sha-ho.”

Rachel’s words not only embody the tragedy she went through, but without a doubt showcase the immense respect she has for the Caddo people and her knowledge of the language as well as the culture (Galan, 2019).

Visitors Experiences:

According to Trip Advisor, the Caddo Mounds site has a 4.5 star rating, and a total of 36 reviews, 18 of which are excellent, 12 are very good, 5 are average, 0 poor, and 1 terrible. After looking into the terrible review, it was noted that this review was submitted only a few months after the tornado, and simply states that not much has been done to repair damage.

As this site has not officially reopened, I do not believe this review can even be considered as the reviewers could not have engaged in the site. The other reviews all agree that the site is “interesting”, “well worth the stop”, and “a great learning experience”. One of the other negative remarks is that it is quite a bit of a walk, which could be a hinderance for those incapable of walking the distance (www.tripadvisor.com, n.d.). Facebook only had 9 reviews for the site, all of which were 5 star ratings (www.facebook.com, n.d.).

Future Agenda:

During the phone interview, Rachel stated that the new exhibits at the site will emphasize the influence and impact that this culture had on the foundations of East Texas and the area as a whole. Rachel and Victor plan to continue working with the Caddo Nation to not only expand but improve public knowledge and education about the customs and cultures of the Caddo People. Most recently, an outreach program has been established inviting Caddo artists to create ceramics, textiles, jewelry, art, or any other items to display in the visitor’s center. Additionally, plans to construct an interpretive garden that will serve as a timeline of Caddo agriculture are also being designed. The Caddo Story of the Snake Women will be the inspiration for the garden, as seen below:

“The Great Father gave the seeds of all growing things to Snake-Woman. He taught her how to plant the seeds and how to care for the green things that grew from them until they were ripe, and then how to prepare them for food. One time, when Snake-Woman had more seeds than she could possibly care for, she decided to give some to the people. She called her two sons and asked them to help her carry the seeds. Each put a big bag full of seeds on his back, and then they traveled all over the world, giving six seeds of each kind of plant to every person. As Snake-Woman gave each person the seeds she told them that they must plant them, and must care for the plants that grew from them, but must allow no one, especially children, to touch them or even point to them as they grew. She said that until the seeds were ripe they belonged to her, and if any one gathered them too soon she would send a poisonous snake to bite him. Parents always tell their children what Snake-Woman said, and so they are afraid to touch or go near any growing plants for fear a snake will come and bite them”.

The garden will also include typical Native American herbs/medicines, such as yarrow, sumac, rosemary and mint, as well as small amounts of agricultural crops like maize, papaya, beans, peppers, potatoes, squash, and tomatoes (Galan, 2019).

References

- Caddo Mounds State Historic Site. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/pg/visitcaddomounds/reviews/. Accessed November 8 2019.

- Caddo Mounds State Historic Site. Trip Advisor. https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowUserReviews-g30160-d293123-r713876330-Caddo_Mounds_State_Historic_Site-Alto_Texas.html. Accessed November 8 2019.

- Galan, Rachel. Telephone interview. October 24 2019.

- Galan, Rachel. Figures 1-15 personal photographs, courtesy of Mrs. Galan.

- Goolsby, Dana. 2010. Caddo Mounds State Historic Site Caddo Indian Culture Day. Texas State Parks. https://www.texasescapes.com/DanaGoolsby/Caddo-Mounds-State-Historic-Site.htm. Accessed October 18 2019.

- 2011. Caddo Mounds State Historic Site: An East Texas Ancient Civilisation. https://myetx.com/caddo-indian-mound-state-historic-site-an-east-texas-ancient-civilisation/, Accessed October 18 2019.

- Gregory, Hiram F. 1986. The Southern Caddo: An Anthology. New York: Garland.

- National Park Service. 2018. El Camino Real de los Tejas: A Brief History. https://www.nps.gov/elte/learn/historyculture/index.htm. Accessed November 1 2019.

- O’Connor, Mallory. 1995. Lost Cities of the Ancient Southeast. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida.

- Perttula, Timothy K. 1992. The Caddo Nation”: Archaeological and Ethnohistoric Perspectives. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Smith, Todd F. 1994. The Red River Caddos: A Historical Overview to 1835. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 64.

- Story, Dee Ann. 1990. Cultural History of the Native Americans. Archeology and Bioarcheology of the Gulf Coast Plain. Research Series No. 38, Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Archeological Survey.

- Swanton, John R. 1942. Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 132, Washington: GPO.

- Texas Historical Commission. 2017. Historic Preservation and Sustainability: The THC’s Position on Sustainability. https://www.thc.texas.gov/preserve/buildings-and-property/historic-preservation-and-sustainability. Accessed October 23 2019.

- Texas Historical Commission. 2017. Grants and Fundraising. https://www.thc.texas.gov/preserve/projects-and-programs/museum-assistance/grants-funding. Accessed October 23 2019.

- The Summerlee Foundation. 2019. Texas History Grants for Fiscal Year Ending June 30 2019. https://summerlee.org/recent-grants/texas-history-grant-list/. Accessed November 1 2019.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal