Tools and templates for an effective systematic literature review

Info: 3179 words (13 pages) Blog

Published: 02 May 2025

For help from a UK subject specialist with writing your systematic literature review, see our systematic literature review service page.

Completing a systematic literature review can feel overwhelming – but the right tools can make each step much more manageable. From framing your research question to searching databases, screening studies, and writing up your findings, a variety of free and paid tools are available.

Download a copy of our free template and planning document here.

1. Research question frameworks (PICO, PEO, etc.)

A well-defined research question is the foundation of any systematic review. Using a question framework helps ensure your question is focused and answerable. Two popular frameworks are PICO and PEO (among others):

PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome)

Commonly used in health and clinical reviews to break a question into key components (e.g. Population: who? Intervention: what is being done? Comparison: compared to what? Outcome: what is measured?). This structured approach clarifies what exactly you’re investigating and guides your literature search. For example, a PICO question might be: “In adults with anxiety (Population), does mindfulness meditation (Intervention) compared to no treatment (Comparison) improve anxiety symptoms (Outcome)?”

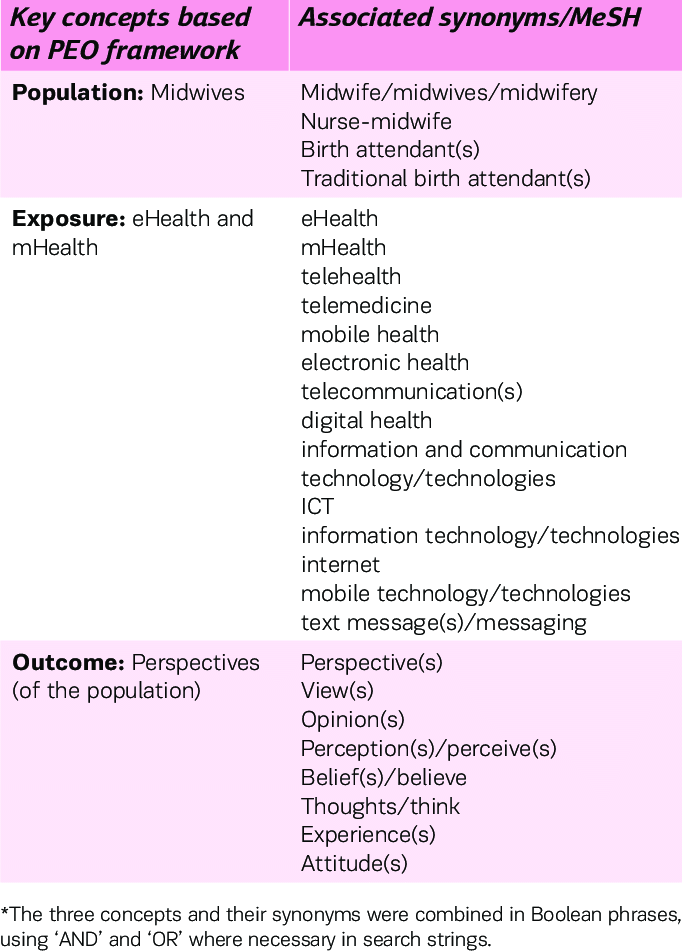

PEO (Population, Exposure, Outcome)

Often used for qualitative or epidemiological reviews. Instead of an “intervention,” PEO considers an Exposure (like a condition or experience). For instance: “Among university students (Population), how does social media use (Exposure) influence academic performance (Outcome)?” This short video explains how to use the PEO framework to develop your search strategy.

Other frameworks

Other frameworks like SPIDER or SPICE exist (there are at least 38 to choose from), but the key is to pick one that fits your topic. Many university libraries provide templates or worksheets for these frameworks. Using a framework provides a structure which can help you to clearly define your research question.

2. Search strategy templates

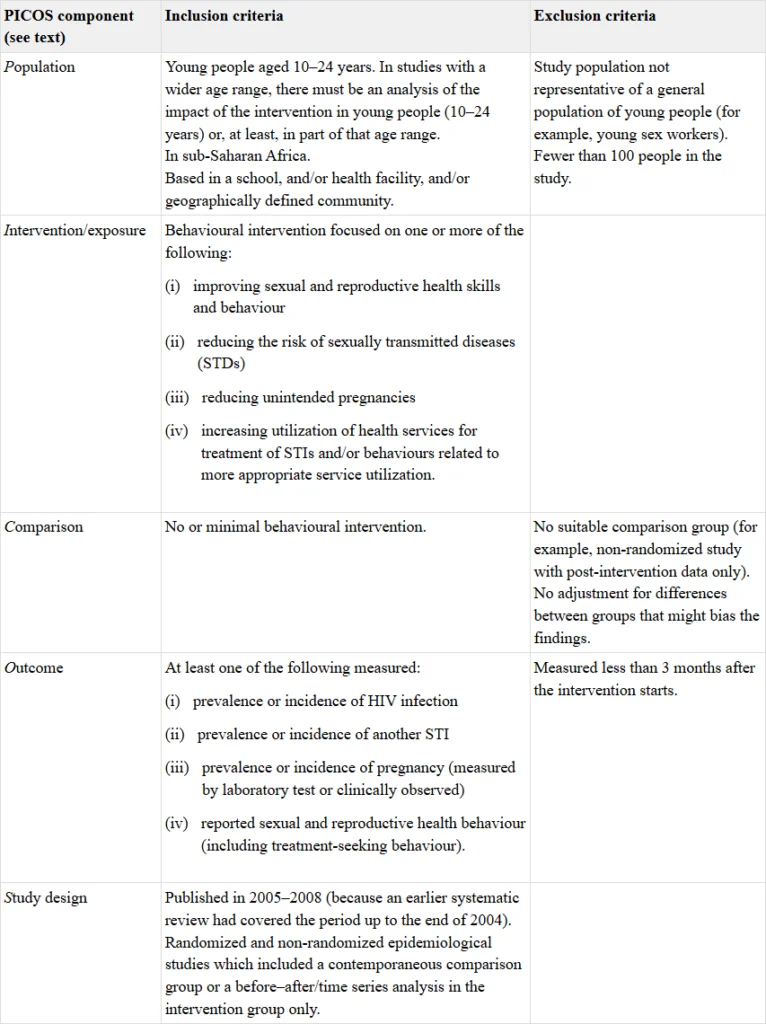

Up-front planning will save you loads of time when searching the literature. Two simple planning tools you should use are inclusion/exclusion criteria lists and search strategy tables:

Inclusion/exclusion criteria checklist

Define before you search what studies you will include or exclude. Criteria might involve study type (e.g. only peer-reviewed journals, no dissertations), population characteristics (e.g. age group, region), date ranges, language, etc. Writing these criteria in a checklist or table will help you stay consistent when screening results. It also makes your review more transparent and importantly, replicable – by clearly documenting why certain studies were filtered out.

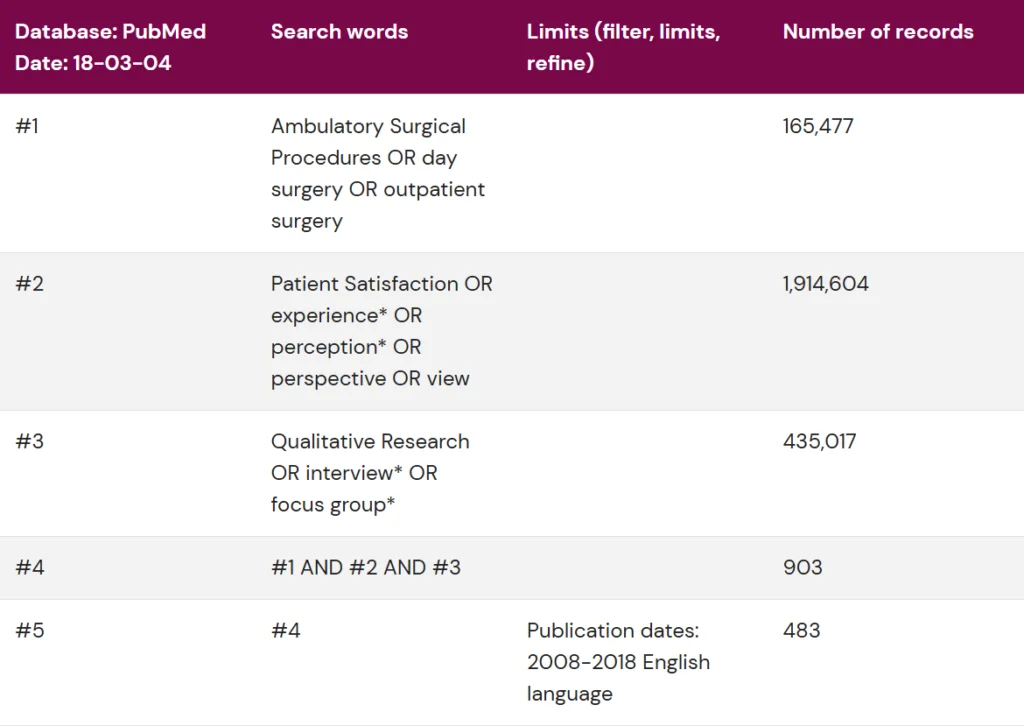

Search strategy table

This is essentially a table where you break your question into key concepts and brainstorm synonyms or related terms for each. For example, if one concept is “university students,” related terms might include “college students,” “undergraduates,” etc. You then mix-and-match these in database searches. The table might have columns for each concept and rows listing terms, and additional rows for how you combine them (using Boolean operators AND/OR). By planning your search strings in a table, you ensure a comprehensive search and you have a record of exactly how you searched each database (which is useful for the methods section of your review). Many libraries offer literature search planning templates for this purpose – or you can create your own in Word or Excel. There is a really excellent free guide to advanced search techniques here. You can also download a helpful search strategy planner here from the University of Derby.

Planning your inclusion criteria and search terms in advance will make the next step – the actual searching – much more effective.

3. Intelligent literature search tools

Finding the relevant literature is at the heart of a systematic review. Beyond the usual academic databases, you can leverage AI-powered tools and smart search services to discover papers faster and more efficiently:

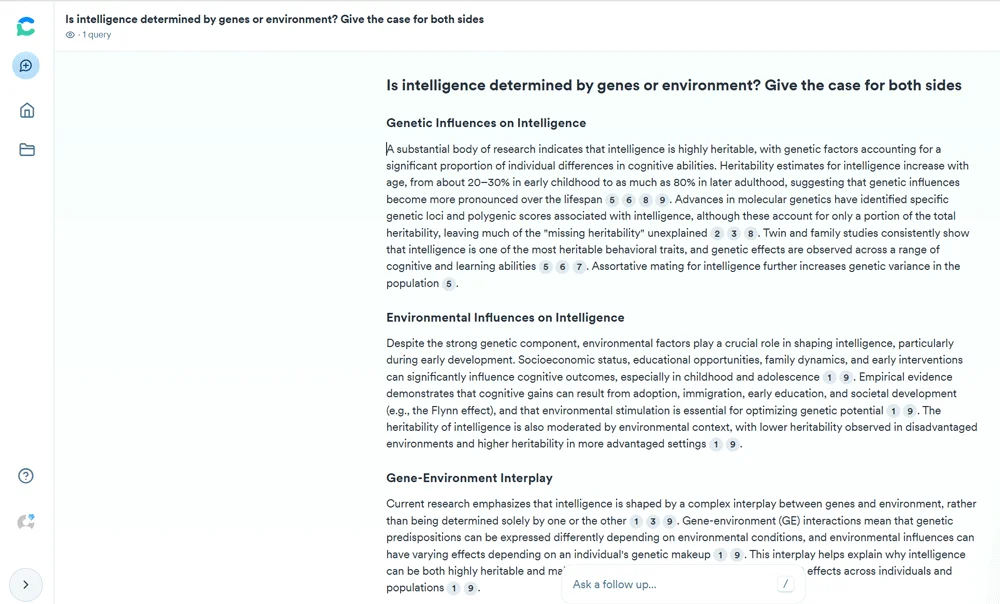

Consensus

Consensus (available at Consensus.app) is an AI-driven academic search engine. You can type in a research question and it uses natural language processing to find relevant scientific papers and even pulls out the consensus of findings. This tool helps you “find the most relevant and reliable research papers, faster” by using AI to scan a huge database of publications. For students, Consensus can speed up the preliminary literature review process by highlighting key results in response to your query. Keep in mind, it’s a supplement to – not a replacement for – thorough database searches, but it’s excellent for getting a quick sense of what the literature says on a question. (The free version gives you 10 “pro” analyses per month and a lot more.)

Elicit

AI research assistant (from Ought.org) is Elicit. Similar to Consensus, you can ask it a question and it will retrieve relevant papers (often with summaries of the abstracts or key points). Elicit also helps with tasks like finding sample size, methodology info from papers, etc. It’s a handy AI tool to support literature discovery and can even suggest potential papers you might miss via traditional keyword searches. The basic version is free and suitable for casual searches.

Subject databases & search engines

Of course, you should still use traditional databases like Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, or your field’s major databases. These remain essential tools for comprehensive searching. If your university library has a discovery service or specific database subscriptions, make full use of them. Many databases have alert features and advanced search builders that allow you to save search strategies. Also consider using tools like Library Access browser extensions (e.g. Lean Library, LibKey Nomad) which can help find full-texts through your library subscriptions while you search the web.

Combining smart AI search with traditional database searching ensures you cast a wide net. The AI tools can surface quick insights and find relevant papers faster. Always cross-check results from AI tools with database searches for completeness.

4. Screening and study selection tools

Once you’ve gathered a large set of articles from your searches, the next challenge is screening them (first by title/abstract, then by full text) against your inclusion criteria and selecting the final studies for your review. This step can be extremely time-consuming, but several tools can help you manage and document it:

Rayyan

Rayyan is a free web application specifically designed to help with systematic review screening. You can import all your references (from databases in formats like RIS/CSV), invite co-reviewers if you’re working in a team, and then go through titles/abstracts, marking studies as Include, Exclude, or Maybe. Rayyan lets you apply labels or keywords, do blinded screening (useful if multiple reviewers to reduce bias), and it can detect and flag duplicates upon import (saving you the headache of manual deduplication). It works offline in a browser and syncs when online. Cost: Rayyan has a free plan with limitations and a low-cost student plan.

Covidence (Paid)

Covidence is another popular systematic review management tool, widely used in academic research. It streamlines screening, data extraction, and even helps with risk of bias tables. Covidence is fee-based for most users (with subscription plans). However, it offers a free trial for one review and is free for Cochrane Collaboration authors.

If your university subscribes to Covidence or if you’re planning an extensive review (like a thesis or dissertation), it might be worth using for its all-in-one features (deduplication, screening interface, data extraction forms, etc.). Otherwise, for class assignments or smaller projects, free options like Rayyan usually suffice.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Generators (Free)

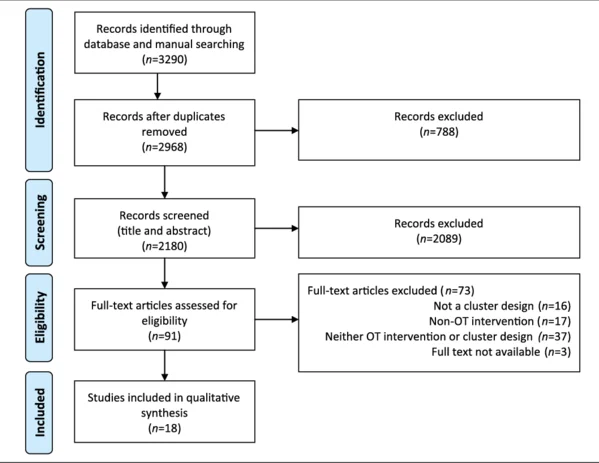

As you screen studies, you’ll need to document the flow of records through the selection process. The standard way to do this is with a PRISMA flow diagram – a chart showing how many results were found, how many duplicates removed, how many studies excluded at each stage and why, and how many ultimately included. Rather than drawing this by hand, you can use free tools to generate a PRISMA diagram.

For example, the PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram Shiny App (an online tool by Neal Haddaway et al.) lets you input your numbers and it creates an up-to-date PRISMA diagram for you. You can access it online (no install needed) at PRISMA Flow Diagram Shiny App and download the diagram as PNG, PDF, or even an interactive HTML. Another option is to use one of the PRISMA templates provided by the Prisma-statement.org website (they offer Word templates for different scenarios). These tools ensure your reporting is PRISMA-compliant with minimal hassle. (Remember to update the diagram later if you remove any additional studies during full-text review.)

Inclusion/Exclusion Tracking (Free)

It’s good practice to keep a table (even just in Excel or Word) to log the studies you exclude at the full-text stage and the reasons for exclusion (e.g. wrong population, irrelevant outcome, etc.). Some tools like Covidence will capture this as you mark reasons for exclusion, but if you’re doing it manually, a simple spreadsheet does the job. This information often accompanies the PRISMA diagram in the appendix or text of your review to show transparency.

By using tools like Rayyan or Covidence for screening and documenting your process with a PRISMA diagram, you’ll make the selection phase more efficient and ensure you have a clear record of how you went from thousands of search results to the final set of included studies.

5. Critical appraisal checklists (quality assessment)

After selecting the studies for inclusion, the next step is often to critically appraise their quality. Systematic reviews usually include an assessment of each study’s strengths and weaknesses (risk of bias). Thankfully, you don’t have to invent criteria for this – there are established checklists that serve as tools for appraisal:

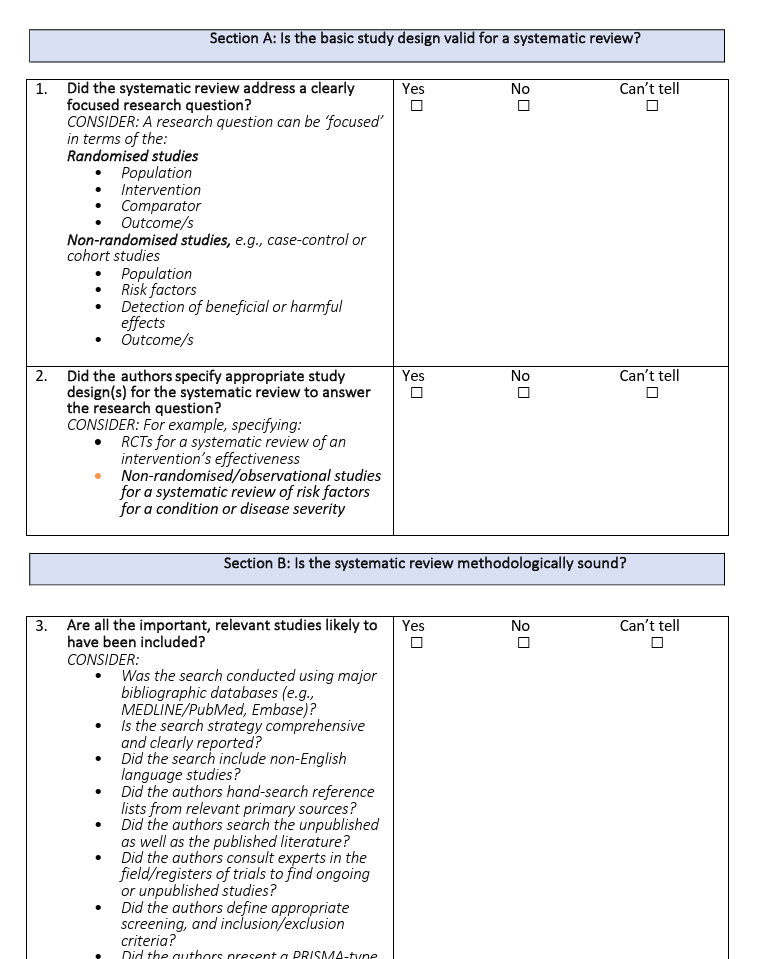

CASP Checklists (Free)

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) offers a suite of free downloadable checklists for different study types, including one for systematic reviews. The CASP Systematic Review Checklist, for example, walks you through 10 questions to evaluate a review’s validity, results, and relevance. Similarly, CASP has checklists for randomised controlled trials, qualitative studies, cohort studies, etc. Using a checklist helps ensure you consistently evaluate each study on important criteria (like: Was the methodology sound? Are the results credible? Were all outcomes reported?). You can get the CASP checklists from the official CASP website (in PDF or Word format) and fill them in for each paper, or use them as a guide for writing a narrative assessment.

Other appraisal tools (Free)

Depending on your field, there may be other quality appraisal tools. For example, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools are another set of checklists for various study designs (also freely available online). If you’re reviewing clinical trials, you might use the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) to assess bias in RCTs, or AMSTAR to appraise other systematic reviews (see this AMSTAR checklist). Check if your discipline has a preferred appraisal instrument. However, for most student projects, CASP is widely accepted and easy to use.

Using these checklists, create a table or paragraph in your review summarising the quality of each study (or at least noting if any studies are particularly weak or strong). This step adds credibility to your review by showing you’ve considered the reliability of the evidence, not just summarised it.

6. Data extraction and synthesis tools

With your final set of high-quality studies, you’ll need to extract data from each and then synthesise the findings. Organisation is key here, and a few tools can help collate the information so you can write it up coherently:

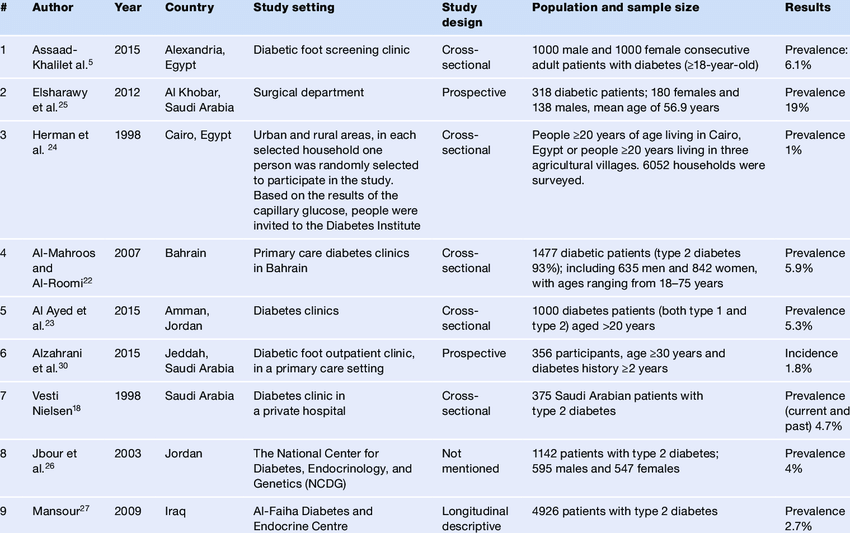

Data Extraction Matrix (Free)

This is simply a fancy term for a table (usually a spreadsheet) where you systematically record all the important information from each study. You might include columns for: authors/year, study design, sample size, population characteristics, interventions/exposures, outcomes measured, key results, limitations, etc. Creating a data extraction matrix in Excel or Google Sheets is highly recommended. As you read each paper, fill in the row. This makes it much easier to compare studies side-by-side. Many systematic reviewers swear by this method to organise evidence – it ensures you don’t miss reporting any critical data and forms the basis for your results sections (and evidence tables in the report).

Synthesis tools

If your review is quantitative (e.g. a meta-analysis), you might use software to statistically pool results. RevMan (from £75/yr for students), the Review Manager software from Cochrane, is a tool for doing meta-analyses and creating forest plots. It also has templates for risk-of-bias tables and such. Another meta-analysis tool is JASP or CMA (Comprehensive Meta Analysis) (CMA is paid, JASP is an open source project and is completely free) or even programming in R with packages like meta or metafor (advanced).

For a typical student assignment, you might not need these unless you are combining effect sizes. If your review is qualitative or mixed-methods, synthesis might involve thematic analysis – tools like NVivo (paid) or ATLAS.ti (paid) can help manage qualitative data/coding, but they are expensive and likely unnecessary for small-scale projects (unless provided by your university). In most cases, narrative synthesis can be done with good old Word processing. Simply put, you can use your extraction matrix to write a structured summary of findings across studies.

Evidence mapping tools (Optional)

If you are a visual thinker, you could use mind-mapping or concept mapping tools (like XMind or MindMeister). Such tools can visually connect themes or findings across studies. There are also some specialised tools (e.g. Connected Papers or Research Rabbit) that graph relationships between papers, which can be insightful for seeing clusters of literature. These aren’t traditional systematic review requirements. However, they can be fun to explore if you want to identify how studies relate to each other.

At the end of extraction, you should have a clear organised set of data from all studies. This makes writing the results and discussion much easier – you can group studies by:

- themes;

- interventions, or;

- outcomes.

In turn, you’ll be able to synthesise what the evidence shows. The main “tool” here is ultimately often just a well-structured table. But leveraging software for meta-analysis or qualitative synthesis is a bonus if applicable.

7. Reference management and citation tools

Throughout the review process, you’ll be accumulating dozens (if not hundreds) of references. Managing these manually is a recipe for frustration. Instead, use reference management tools to keep track of all citations and format your references correctly:

UKEssays’ referencing generators (Free)

If you need to get a citation formatted correctly without going through a lengthy registration process, or you only have a few sources, you can use the free referencing generators provided by UKEssays. They offer easy-to-use tools for Harvard, Vancouver, APA 7th edition and more:

An OSCOLA referencing generator can be found on sister site Lawteacher.net.

Simply choose the style, enter the details of the source (title, author, publication info, etc.). In turn, it instantly creates a properly formatted reference for you with no registration required. This can save you time and ensure your citations are error-free. For instance, the Harvard Reference Generator will format a book, journal, website, or many other source types into the correct Harvard style automatically. (Of course, double-check the output, and be sure to have all necessary source info.) These generators are handy learning tools as well – seeing the formatted result can teach you the nuances of each style.

Other referencing tools for an effective systematic literature review

For a more robust solution, we have reviewed the best referencing tools here.

Whichever reference tool you use, start using it early – import references as you find them. This way, when you’re writing the review, you can insert citations on the fly. It will also make alphabetising and formatting the bibliography at the end a one-click task rather than a manual nightmare. Good reference management tools not only save time but also help avoid accidental plagiarism by keeping clear track of what information came from where.

8. Writing, editing, and plagiarism-checking tools

Finally, after all the research comes the actual writing of the systematic literature review. At this stage, clarity, proper academic style, and originality are paramount. Several tools and services can assist you in polishing your work:

Viper plagiarism scanner (Paid)

Before you submit your review, it’s wise to run it through a plagiarism checker to ensure you haven’t inadvertently too closely paraphrased any source. Viper is an online plagiarism checker (from ScanMyEssay) that serves as a low-cost option. It allows you to upload your document and scans it against over 10 billion sources (web pages, publications, and its own database).

Viper provides a detailed report highlighting any matches and their sources. The interface is student-friendly, and importantly, it does not store your paper in any public database (so you retain your work’s privacy). Using Viper can give you peace of mind that your work is original before your university checks it.

UKEssays’ writing and editing service (Paid)

Systematic literature reviews are challenging to write, and if you feel you need expert help, UKEssays offers a Systematic Literature Review writing service that can assist at any stage. This is a professional service where you can get a qualified academic writer to help research and write your literature review or a portion of it, or even just proofread/edit your draft. The service is tailored to your needs – whether you require a model example to guide you or a thorough edit to refine your own work.

Using this service can show you “how an expert formulates a research question and approaches the research task,” giving you a template to learn from for your own work. All work provided is original and customised to your assignment criteria, with guarantees against plagiarism. Of course, this is a premium option (prices vary by level and word count – for instance, a part of a review can start around a few hundred pounds), so it’s usually considered if you’re really struggling or aiming for a very high standard. If you do choose to use such a service, use it ethically – as a learning aid – and ensure you understand your university’s stance on writing help. The bottom line is that this option exists for additional support, especially if time is short or the stakes are high in your final year.

Remember, the writing phase is where all your hard work comes together. Take the time to outline your review (e.g. organise by themes or chronologically, as appropriate), and use the tools above to ensure your final text is coherent and well-polished. Even the best tools can’t replace your own critical thinking, so while they help with mechanics, make sure your voice and analysis come through in the writing.

For help from a UK subject specialist with writing your systematic literature review, see our systematic literature review service page.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below: