Refining Practitioner Skills for Patient Care

| ✓ Paper Type: Free Assignment | ✓ Study Level: University / Undergraduate |

| ✓ Wordcount: 9230 words | ✓ Published: 06 Jun 2019 |

- Incident Details: 67 year old (Female) who had a fall; ankle injury.

Case study one: Appraisal of Ankle Injury Assessments in Pre-hospital setting.

| PC | Fall – Right Ankle injury | |||

| HxPC | The patient was walking up 5 stairs to her home when she tripped and fell up the stairs landing on her right ankle awkwardly. The patient fell on the concrete floor, the patient sat for a minute and then with help from her husband was able to get up. The pain then limbed to the front room and put her foot up on the sofa. The concrete ground was dry. The patient was wearing sandals on her feet at the time. The patient has had no previous injuries to right ankle or foot. The patient states she has not hurt or injured herself anywhere else, no pain or discomfort anywhere apart from her right ankle. The husband was right behind her and witness everything. The patient did not hit her head, no LOC. No c-spine tenderness on palpation or movement. The patient states that the ankle swelled straight away and bruising appeared soon after. The patient has not taken any analgesia for the pain. | |||

| PMHx | Asthma | |||

| FMHx | No family history of osteoporosis. | |||

| MHx | Ventolin inhaler – maximum of 4 times a day or PRN. | |||

| Allergies | Known None. | |||

| SHx | Lives with husband in a house. Patient believed not to be under the influence of any alcohol or drugs. Non-smoker. | |||

| O/A | Patient sat on sofa with her leg raised with no shoe on the right foot. Patient talking in full sentences, alert and GCS 15/15.

|

|||

| O/E | ||||

| RS |  Slight increased RR at 24. SP02 96% (Air). Equal air entry. Equal rise and fall.Trachea central. Slight increased RR at 24. SP02 96% (Air). Equal air entry. Equal rise and fall.Trachea central.

Equal resonance throughout. Chest sounds: clear. (Health References, 2012). |

|||

| CVS | HR 78. BP 130/82. Cap Refill <2. | |||

| CNS | Temp 36.7 | |||

| ABDO | NAD | |||

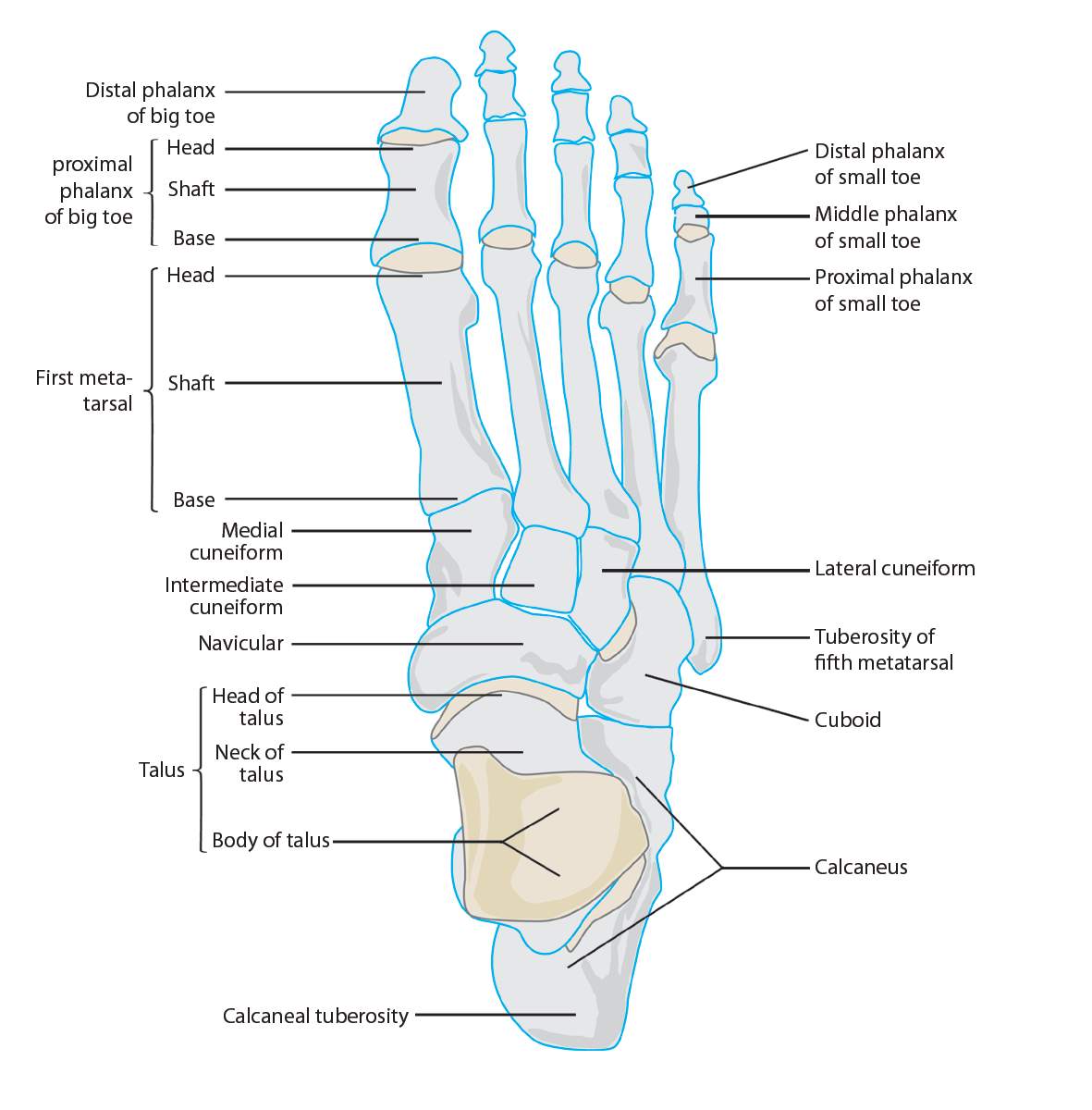

| LMS | Patient states she did not hurt or injury herself anywhere else apart from her right ankle. No pain of discomfort in left leg, both arms, neck and back.Look: Swelling to right ankle. No gross deformity.

Palpate: Well perfused cap refill <2 Peripherals. Warm to touch. Good pedal pulse. No pain, discomfort or swelling over the patella, or over the head of the fibula. Ligaments appear intact. No loss of sensation. No pain, discomfort or swelling down the tibia, fibula and calf. No loss of sensation. Simmons test NAD. Painful on palpation of base of 5th metatarsal. Bruising to and 5th metatarsal. Movement: Unable to do more than 2 steps without being in severe pain. Active: Dorsiflexion/plantarflexion – Able to do but painful. Inversion – Able to but painful Eversion – Not painful. Resistance: Patient seemed in too much pain to be able to resistance movement and as Ottawa Positive I didn’t want to cause any more damage.

|

|||

| IMP/DD | ? # Base of 5th metatarsal and/or ? soft tissue injury (Sprain/Strain) | |||

| Rx |

|

|||

| PLAN | Conveyed patient to A&E. | |||

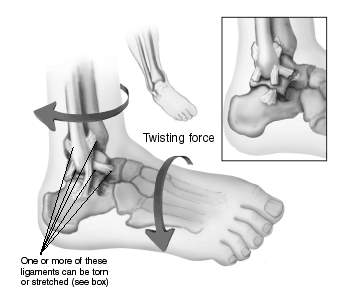

The most common lower limb fracture is the ankle, accounting for 9% of all fractures

(Bugler, White & Thordarson, 2015). Subtle fractures are commonly misdiagnosed as sprained ankle due to clinical presentation similarities (Judd & Kim2002), a thorough initial examination is vital for treatment and positive patient outcome. Common symptoms of a sprained and fractured ankle are sudden pain, swelling, bruising and an inability to walk (Kenny, 2015). The Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000 legislation provides patients and employers protection from the dangers of exposure to unnecessary radiation (Department of Health, 2000), because of this the Ottawa Ankle Rules (OAR) (Stiell, 2016) was implemented.

Implementing the OAR into a pre-hospital setting will enable paramedics to complete a thorough assessment and avoid unnecessary hospital admissions (Simpson, 2010) and radiation exposure (Bachmann et al, 2003).

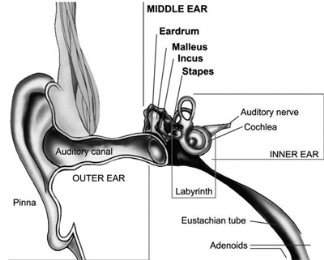

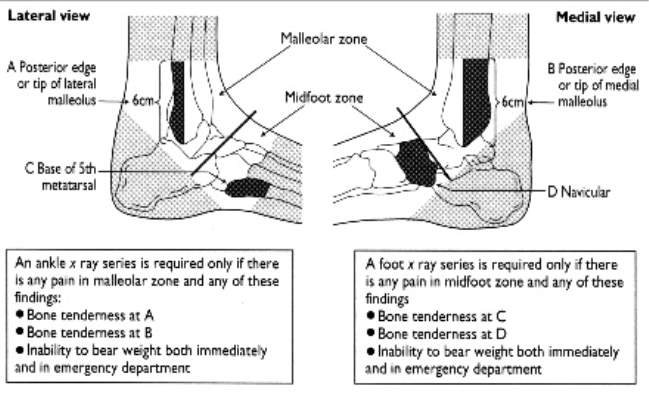

In 1992, the OAR (Appendix 1) was first introduced, the original rules recommended that an ankle X-ray is only required if the patient is: 55 years of age or older, unable to weight bear or walk more than 4 steps, experiencing bony tenderness on the posterior edge or inferior tip of the lateral malleolus and the posterior edge or inferior tip of the medial malleolus (Wright, 2016).

The OAR has a high sensitivity ranging from 96.4% to 99.0%, a negative test finding is an acceptable measurement that there is no fracture present; however, the Buffalo Rule, a modification of the OAR has an even higher sensitivity of 100%, all patients who had malleolar pain had fractures (Jenkin, Sitler & Kelly, 2010). The Buffalo Rule increases accuracy by the tender point measured from the crest or mid-portion of the malleoli, distal 6cm of the fibula and tibia; reducing palpating over ligament injuries (Jonckheer et al., 2015).

Both assessments can potentially decrease the number of patients exposed to unnecessary radiation and reduce the costs associated with ankle injuries. Bachmann’s (2003a) found the OAR could reduce this by 19% to 39%, whereas the Buffalo Rule could reduce this by 54% (Leddy et al, 1998). Although the OAR reduces the need for X-ray without misdiagnosing fractures and soft tissue damage, the Buffalo modifications improve malleolar fracture specificity without sacrificing sensitivity (Miller, Svoboda & Gerber, 2012).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) recommends the OAR as part of the assessment and management in non-complicated factures in patients over 5 years old to determine if an X-ray is required. The Health and Care Professions Council’s (2012, p.3) “you must act in the best interests of service users” (1) and also “act within the limits of you knowledge, skills and experience and, if necessary, refer the matter to another practitioner” (6). This protects patients against unnecessary hazards such as radiation from X-rays or if a paramedic feels deems it necessary from a thorough assessment using the OAR, referring them to another practitioner.

My patient matched one of the criteria of the current OAR and therefore guided our clinical decision to convey the patient to accident and emergency for an X-ray.

References

- Bachmann, L, Kollo, E, Koller, M, Steurer, J, Riet, G. (2003). Accuracy of Ottawa Ankle Rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. British Medical Journal. Vol. 326:417.

- Bugler, K.E., White, T.O and Thordarson, D.B. (2015) Ankle fractures. Available at: https://www.boneandjoint.org.uk/content/focus/ankle-fractures (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

- Department of Health (2000). The Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

- Docpods (2017). Metatarsal Anatomy. Available at: https://www.docpods.com/metatarsal-anatomy (Accessed: 12 December 2017).

- Health and Care Professions Council (2012) ‘Standards of Conduct Performance and Ethics.’ (Accessed: 12 December 2016)

- Health References (2012). Lungs. Available at: https://www.healthsanaz.com/lungs-drawing-for-kids-ldk08.html (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

- Jenkin, M., Sitler, M.R. and Kelly, J.D. (2010) ‘Clinical usefulness of the Ottawa ankle rules for detecting fractures of the ankle and Midfoot’, National Centre for Biotechnology Information, 45(5), pp. 480–482.

- Jonckheer, P., Willems, T.M., De Ridder, R. and Roosen, P. (2015) Evaluating fracture risk in acute ankle sprains: Any news since the Ottawa Ankle Rules? A systematic review. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287958805_Evaluating_fracture_risk_in_acute_ankle_sprains_Any_news_since_the_Ottawa_Ankle_Rules_A_systematic_review (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

- JRCALC (2016). Clinical practice guidelines: Entonox, Paracetamol and Morphine. (4th ed). Bridgewater: Class Professional Publishing

- Judd, D. and Kim, D. (2002) Foot fractures frequently Misdiagnosed as ankle sprains. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2002/0901/p785.html (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

- Kenny, T. (2015) Ankle Injuries. Available at: https://patient.info/health/ankle-injuries-leaflet (Accessed: 12 February 2017).

- Leddy JJ, Smolinski RJ, Lawrence J, Snyder JL and Priore RL. (1998) Prospective evaluation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules in a university sports medicine center: with a modification to increase specificity for identifying malleolar fractures. Am J Sports Med. 26(2): 158–165.

- Miller, J.M., Svoboda, S.J. and Gerber, P.J. (2012) ‘Diagnosis of an isolated posterior malleolar fracture in a young female military cadet: a resident case report’, National Centre for Biotechnology Information, 7(2), pp. 167–172.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) Fractures (non-complex): Assessment and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng38 (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

- Simpson, P.M. (2014) ‘Use of the Ottawa ankle rule by paramedics in the out-of-hospital setting’, Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care, 8(2), pp. 1–7.

- Stiell, I. (2016) Ottawa ankle rule. Available at: https://www.mdcalc.com/ottawa-ankle-rule (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

- Wright, M. (2016) Ankle fractures. Information about broken ankle. Patient. Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/ankle-fractures (Accessed: 12 December 2016).

Appendix

Appendix 1: Ottawa Ankle Rules

Appendix 1: Ottawa Ankle Rules

CASE STUDY TWO

- Incident Details: 4 year old boy with mild croup

Case study two – Evaluation of Dexamethasone in croup

| PC | Breathing difficulties | |

| HxPC | The patient had cold symptoms for 4 days. The patient woke up around 2am with a barking cough and stridor at rest. The last episode of croup that the patient had was 12 months ago. The patient has not been abroad recently and not been in contact with anyone who has been poorly recently. Slightly off food but has been drinking a lot more than usual. No diarrhoea or vomiting. Patient is still opening his bowels as normal and passing urine as normal. | |

| PMHx | Has had croup every year since birth. This was his 4th episode.Vaccinations up to date: Measles, mumps and rubella. | |

| FMHx | Mum used to suffer with croup when she was young. Otherwise no family history of respiratory problems. | |

| MHx | None. Normally fit and well. | |

| SHx | Patient lives with mum, dad and his little brother in their house. The patient goes their local nursey. The house is a smoke free house. | |

| O/A | Patient sat on sofa with dad watching television. Patient able to answer nodding his head or answering yes or no (seemed shy at first), alert and GCS 15/15. Using the patient triangle assessment tool the patient had rosy cheeks, normal neurological response and increased respiratory rate on initial look. | |

| O/E | ||

| RS |  Increased RR at 38. SP02 97% (Air). Patient was using accessory muscles. No tracheal tug present. No respiratory recession. Not cyanosed. Patient had a barking cough.Chest sounds were clear. Increased RR at 38. SP02 97% (Air). Patient was using accessory muscles. No tracheal tug present. No respiratory recession. Not cyanosed. Patient had a barking cough.Chest sounds were clear.

Equal rise and fall. Trachea central. Equal resonance throughout. (Health References, 2012). |

|

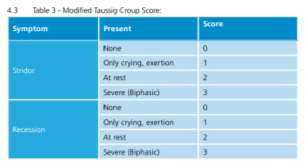

| RS |  Using the modified Taussig Croup Score the patient scored 1 (Only on exertion).(South Western Ambulance Service Trust, 2014) Using the modified Taussig Croup Score the patient scored 1 (Only on exertion).(South Western Ambulance Service Trust, 2014) |

|

| CVS | HR 150. Cap Refill <2. | |

| CNS | Temp 37.4. BM 4.2 PEARL 3mm | |

| ABDO | NAD | |

| LMS | NAD | |

| OTHER | No mottled skin, or rashes. Peripheries warm to touch. Throat: Moist mouth and tongue, throat not inflamed, red or sore. Straight uvela and tonsils not raised, red and no pits or puss. | |

| IMP/DD | Mild Croup | |

| Rx |

Patient’s observations improved: SP02 98% RR 30 HR 136 TEMP 36.8 No stridor present and the barking cough improved. The patient was happy chatting with us and watching television. |

|

| PLAN | Non-convey. Safety netting put into place: worsening advice given, patient left in care of parents. A croup leaflet left with parents. | |

Croup is a viral respiratory tract illness affecting children between 6 months and 3 years; however, it can affect children up to the age of 15 (SWAST, 2014). It causes swelling to the vocal cords causing the barking cough, any swelling narrows the airway and can obstruct breathing in severe cases (Sears, 2013). Some children may have cold-like symptoms a few days before developing croup symptoms (NHS, 2014). Using the modified Taussig Croup Score, croup is split into severity categories; mild (scoring 1-2), moderate (scoring 3-4) or severe (scoring 5-6). The case study patient scored as mild (JRCALC 2013). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2012) states that mild croup symptoms are; “occasional barking cough and no audible stridor at rest, no or mild suprasternal and/or intercostal recession and the child is happy, eating, drinking and playing”. Mild croup with no signs of moderate or severe/life-threating croup can be managed at home with administration of Dexamethasone (Dex) (SWAST, 2014)

Mild croup is generally self-limiting but a single dose of a corticosteroid is beneficial (British National Formulary for Children, 2017). A single dose of Dex should be administered to all children with mild, moderate or severe croup (NICE, 2012). One of the benefits of using corticosteroid is that its biological half-life is between 36 – 72 hours (SWAST, 2014).

The benefits of giving this drug to moderate or severe croup is well established but not for mild croup (McMorran, 2016). Bjornson et al’s (2004) randomised trial of a single dose for mild croup found that Dex is an effective treatment; quicker resolution of symptoms, less lost sleep and less stress for the parents. However, the long-term effects in mild croup is unknown (Kermode-Scott, 2004). O’Mara (2005) also supports the use of Dex as it reduces loss of sleep for the child and the chances of returning to medical care. Corticosteroids can have immunosuppressive effects which can lead to infectious complications, although this is rare it is still a concern when administering to children with mild croup (James, 2008). The advantage of Dex is that it works quickly within 30 minutes if the child is having a single dose (Dobrovoljac, 2011). A disadvantage is that child may find it unpleasant to taste and can cause vomiting in some cases, therefore the child may not get the correct dose needed to resolve the croup symptoms (Solemiani et al, 2013).

The long-term effect of Dex is unknown; however, Bjornson et al’s (2004) study supports the use in children with croup. Dex is an effective treatment for children with mild croup, it is an easy and low-cost therapy which relieves symptoms and has social and economic benefits (Evidence-Based Healthcare & Public Health, 2005). Children who receive oral Dex are less likely to need medical care later (Luria, 2001).

Research suggests the use of Dexamethasone in children is vastly beneficial and effective in mild, moderate and severe croup clinically for the patient and emotionally for the parent/guardian(s); these benefits outweigh the potential and rare risks.

References

- Bjornson, C.L., Klassen, T.P., Williamson, J., Brant, R., Mitton, C., Plint, A., Bulloch, B., Evered, L. and Johnson, D.W. (2004) ‘A Randomised trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild Croup’, New England Journal of Medicine, 351(13), pp. 1306–1313. Doi: 10.1056/nejmoa033534.

- British National Formulary for Children (2017) Croup. Available at: https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnfc/current/3-respiratory-system/31-bronchodilators/croup (Accessed: 2 February 2017).

- Dobrovoljac, M. and Geelhoed, G.C. (2011) ‘How fast does oral dexamethasone work in mild to moderately severe croup? A randomized double-blinded clinical trial’, Emergency Medicine Australasia, 24(1), pp. 79–85. Doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01475.x.

- Evidence-Based Healthcare & Public Health (2005) ‘Oral dexamethasone is effective for mild croup in children’, Evidence-based Healthcare and Public Health, 9(2), pp. 167–168. Doi: 10.1016/j.ehbc.2005.01.029.

- Health References (2012). Lungs. Available at: https://www.healthsanaz.com/lungs-drawing-for-kids-ldk08.html (Accessed: 2 February 2017).

- James, D. and Cherry, M.D. (2008) ‘Croup’, New England Journal of Medicine, 358(4), pp. 384–391. Doi: 10.1056/nejmcp072022.

- JRCALC (2013). Clinical practice guidelines: Respiratory illness in children. 4th ed. Bridgewater: Class Professional Publishing. P110-111

- JRCALC (2016). Clinical practice guidelines: Page for age. (4th ed). Bridgewater: Class Professional Publishing. P283

- Kermode-Scott, B. (2004) ‘Corticosteroids may be effective for most cases of croup, study shows’, BMJ, 329(7469), pp. 762–0. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.762-c.

- Luria, J., Gonzalez-del-Rey, J., DiGiulio, G., McAneney, C., Olson, J. and Ruddy, R. (2001) ‘Effectiveness of oral or nebulized dexamethasone for children with mild croup’, Archives of paediatrics & adolescent medicine. 155(12), pp. 1340–5.

- McMorran, J., Crowther, D., McMorran, S., Youngmin, S., Wacogne, I., Pleat, J. and Prince, C. (2016) Steroids in croup – general practice notebook. Available at: https://www.gpnotebook.co.uk/simplepage.cfm?ID=-536477621 (Accessed: 3 February 2017).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2012) Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/croup#!scenario (Accessed: 2 February 2017).

- O’Mara, L. (2005) ‘Dexamethasone reduced the incidence of children with mild croup who returned for medical care’, Evidence-Based Nursing, 8(2), pp. 41–41. Doi: 10.1136/ebn.8.2.41.

- Sears, W. (2013) Croup symptoms and treatment. Available at: https://www.askdrsears.com/topics/health-concerns/childhood-illnesses/croup (Accessed: 2 February 2017).

- Soleimani, G., Daryadel, A., Ansari Moghadam, A. and Sharif, M.R. (2013) ‘The comparison of oral and IM dexamethasone efficacy in Croup treatment’, Journal of Comprehensive Pediatrics, 4(4), pp. 175–8. Doi: 10.17795/compreped-4528.

- South Western Ambulance Service Trust (2014) Management of Croup. Available at: https://www.swast.nhs.uk/Downloads/Clinical%20Guidelines%20SWASFT%20staff/CG26_Croup.pdf (Accessed: 2 February 2017).

- South Western Ambulance Service Trust (2015) Medicines Protocol: Dexamethasone. Available at: https://www.swast.nhs.uk/Downloads/Clinical%20Guidelines%20SWASFT%20staff/SWASFTMedicinesProtocol_Dexamethasone.pdf (Accessed: 2 February 2017).

CASE STUDY THREE

- Student ID: 10191190

- Word count: 514

- Submission date: Monday 8th May 2017

- Module code: Para 301

- Module title: Refining practitioner skills for patient care

- Incident Details: Elderly woman fall non-injury, query urine tract infection in pre-hospital setting.

Case study three – Evaluation of urine dip analysis (Catheterised and non-catheterised patients).

| PC | Non-injury fall | |

| HxPC | The patient had an unwitnessed mechanical non-injury fall at her own home in the carpeted living room. The patient was only wearing socks at the time. The patient had no chest pain and did not feel dizzy before the fall. No recent headaches. The patient feels well in herself. Patient remembers the whole event, the patient did not bang her head and no LOC. | |

| PMHx | AsthmaHypertension

AF |

|

| FMHx | Unknown. | |

| MHx | Ventolin Salbutamol InhalerRamipril

Atenolol |

|

| Allergies | Mushrooms. No medication allergies known. | |

| SHx | Patient lives home alone, has carers in 3 times a day. The patient does have a pendant alarm in place which she push to make contact with the ambulance service. | |

| O/A | Patient was sitting on the floor leaning against the sofa. Patient was conscious and breathing. The patient states she was walking with her frame to the kitchen from the living room when she felt her sock slip on her television magazine which was on the floor and fell to the floor. The patient was unable to get back up due to mobility. | |

| O/E | ||

| RS |  RR 24. Equal rise and fall. SP02 94% (Air) Patient is a heavy smoker and has been all her life. Patient is able to talk in full sentences. GCS 15, (A) VPU. No cough or colds recently. Chest sounds clear.Good lateral air entry. RR 24. Equal rise and fall. SP02 94% (Air) Patient is a heavy smoker and has been all her life. Patient is able to talk in full sentences. GCS 15, (A) VPU. No cough or colds recently. Chest sounds clear.Good lateral air entry.

Equal rise and fall. Trachea central. Equal resonance throughout. (Health References, 2012). |

|

| CVS | HR 66. Cap Refill <2. ECG Normal Sinus Rhythm. Patient denies any chest pain or discomfort. | |

| CNS | Temp 38.4. BM 4.4 | |

| ABDO | No pain or discomfort on palpation, soft abdominal. No guarding or masses. Normal bowel sounds. Eating and drinking as normal for the patient. Patient states her urine has looked dark in colour recently. Patient has been going more often and stings when passing urine. Bowels open as normal. No nausea or vomiting. No scars seen. Patient denies any abdominal pain or discomfort. | ||

| LMS | Patient stated she has not hurt or injured herself and no complaint of any pain or discomfort. No C-spine tenderness on movement or palpation. No red marks or bruises. Patient did not bang her head. Usually uses a frame to mobilise around the flat. | ||

| IMP/DD | ? UTI | ||

| Rx |

Urine Analysis found:

|

||

| PLAN | Non-convey. Safety netting put into place: worsening advice given, patient’s carers coming in within the hour. Antibiotics given. | ||

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common in women and the elderly (WebMD, 2015). The infection can occur in the bladder, kidneys or the connecting tubes (NHS, 2016). This is the second most common bacterial infection seen in the elderly (Ho, 2016); up to 30% of the elderly have a UTI with a mortality rate as high as 33% (Cove-Smith and Almond, 2007). Patients with a catheter are at higher risk of getting a UTI, with 90-100% of patients with long-term catheterization developing a bacterial infection (Brusch, 2015).

UTI symptoms are; burning or stinging feeling when passing urine, increased frequency and urge, pain or pressure in the back or lower abdomen, fever, chills, tiredness, strange smell to urine, dark and cloudy or blood in urine (Smith, 2017). Symptoms of a UTI in a patient with a long-term catheter include; new onset of a fever, altered mental state, tiredness, flank pain and decreased urine output (Sign, 2013).

UTIs are commonly caused by the bacteria infection, Escherichia coli which is easily corrected with antibiotics (British National Formulary, 2014). Non-complicated UTIs are treated with a short course of antibiotics however, men and pregnant women may be given longer courses of antibiotics (NHS, 2016). Patients with a catheter should only be treated if symptomatic (Jarvis, Chan and Gottlieb, 2014) and if symptoms are present a dipstick analysis of urine can be performed (Bates, 2013).

Testing for a UTI using a dipstick is a common, quick and easy to use and low cost (Rehmani, 2004). Dipstick urinalysis is an accurate test to use and supports clinicians when diagnosing patients with a UTI (Sultaria et al, 2001). Bolann, Sandberg and Digranes (1990) found that once the dipstick results were complete, the microscopy did not give any additional information. Kayalp et al’s (2013) study showed urine dipstick and microscopy are accurate tools to use to rule out a UTI however, microscopy is the highest accuracy tool to use when looking for bacteriuria UTI. Similarly, Devillie et al (2004) found that a urine dipstick test is a valuable tool to rule out the presence of an infection with negative results. Therefore, in clinical assessment, dripping urine is an adequate method to diagnose a UTI (Sultana et al, 2001).

When testing asymptomatic catheterised patients, the use of urinary dipsticks is a very effective and cheap diagnostic tool (Tissot et al, 2001). However, Southern Health (2017) suggest, when diagnosing a UTI in a patient with a catheter, dipstick testing is not an accurate tool and should not be used.

In conclusion, when patients are symptomatic the use of dipstick urinalysis is a useful and reliable diagnostic method to support the clinician’s diagnosis of a UTI (Zamanazad, 2009). However, using dipsticks in catheterised patients is an unreliable diagnostic tool and should not be used to diagnose a UTI (Schwartz and Barone, 2006). Emergency Care Practitioners find that dipstick testing for leukocyte esterase and nitrites is a useful, cheap and safe diagnostic tool in the prehospital setting to diagnose certain groups of patients and it is as useful as microscopy and cultures (South Western Ambulance Service, 2014).

References

- Bates, B. (2013). Interpretation of Urinalysis and Urine Culture for UTI Treatment. Uspharmacist.com. Available at: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/interpretation-of-urinalysis-and-urine-culture-for-uti-treatment (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Bolann, B., Sandberg, S. and Digranes, A. (1990). Implications of probability analysis for interpreting results of leukocyte esterase and nitrite test strips. Clinchem.aaccjnls.org. Available at: https://clinchem.aaccjnls.org/content/35/8/1663.long (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- British National Formulary(2014). 5.1.13 Urinary-tract infections: NHS. Available at: https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current/5-infections/51-antibacterial-drugs/5113-urinary-tract-infections (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Brusch, J. (2015). Catheter-Related Urinary Tract Infection: Transmission and Pathogens, Guidelines for Catheter Use, Diagnosis. Emedicine.medscape.com. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2040035-overview (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Cove-Smith, A and Almond, M. (2007). Management of urinary tract infections in the elderly. Trends in Urology, Gynaecology & Sexual Health, 12(4), pp.31-34. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tre.33/pdf (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Devillé, W, Yzermans, J, van Duijn, N, Bezemer, P, van der Windt, D. and Bouter, L. (2004). The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections. A meta-analysis of the accuracy. BMC Urology, 4(1). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC434513/ [Accessed 25 Apr. 2017].

- Health References (2012). Lungs. Available at: https://www.healthsanaz.com/lungs-drawing-for-kids-ldk08.html (Accessed: 25 Apr. 2017).

- Ho, J. (2017). Urinary Tract Infections in the Elderly. Mercury Pharmacy Services. Available at: https://www.mercuryrx.com/single-post/2016/11/28/Urinary-Tract-Infections-in-the-Elderly (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Jarvis, T., Chan, L. and Gottlieb, T. (2014). Assessment and management of lower urinary tract infection in adults. Australian Prescriber, 37(1), pp.7-9. Available at: https://www.nps.org.au/australian-prescriber/articles/assessment-and-management-of-lower-urinary-tract-infection-in-adults (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017)].

- Kayalp, D., Dogan, K., Ceylan, G., Senes, M. and Yucel, D. (2013). Can routine automated urinalysis reduce culture requests? Clinical Biochemistry, [online] 46(13-14), pp.1285-1289. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0009912013002920 (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- NHS (2016). Urinary tract infections (UTIs) in adults – NHS Choices. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Urinary-tract-infection-adults/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Rehmani R (2004). Accuracy of urine dipstick to predict urinary tract infections in an emergency department. – PubMed – NCBI. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15125171 (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Schwartz DS, Barone JE. (2006) Correlation of urinalysis and dipstick results with catheter-associated urinary tract infections in surgical ICU patients. Intensive Care Med; 32:1797–1801.

- Sign.ac.uk. (2013). SIGN Guideline 88: Management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults – section 6. Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/88/section6.html (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Smith, M. (2017). A Guide to Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs). WebMD. Available at: https://www.webmd.com/women/guide/your-guide-urinary-tract-infections#1 (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- South Western Ambulance Service. (2014). Urinary tract infection in children: Diagnosis, treatment and long-term management. Available at: https://www.swast.nhs.uk/Downloads/SWASFT%20NICE%20action%20plans/ActionPlan_14-13UTIChild.pdf (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Southern Health (2017). Urinary Catheter Care Guidelines. Available at: https://www.southernhealth.nhs.uk/EasysiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=70589&type=full&servicetype=Inline (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Sultana, R., Zalstein, S., Cameron, P. and Campbell, D. (2001). Dipstick urinalysis and the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of urinary tract infection. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, [online] 20(1), pp.13-19. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0736467900002900 (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Tissot, E., Woronoff-Lemsi, M., Cornette, C., Plesiat, P., Jacquet, M. and Capellier, G. (2001). Cost-effectiveness of urinary dipsticks to screen asymptomatic catheter-associated urinary infections in an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine, 27(12), pp.1842-1847. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11797017?dopt=Abstract (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- WebMD. (2015). Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) in Older Adults-Topic Overview. Available at: https://www.webmd.com/women/tc/urinary-tract-infections-utis-in-older-adults-topic-overview (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

- Zamanzad, B. (2009). Accuracy of dipstick urinalysis as a screening method for detection of glucose, protein, nitrites and blood. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. Available at: https://applications.emro.who.int/emhj/1505/15_5_2009_1323_1328.pdf (Accessed 25 Apr. 2017).

Plymouth University

Faculty of health and human sciences

School of health professionals

CASE STUDY FOUR

- Student ID: 10191190

- Word count: 537

- Submission date: Monday 8th May 2017

- Module code: Para 301

- Module title: Refining practitioner skills for patient care

- Incident Details: 72 year old, male dog bite to left thumb self-presented at the local minor injuries unit.

Case Study Four: Evaluation of cleaning Wounds; Saline Verses tap water

| PC | Dog bite – two puncture wounds to left thumb | |

| HxPC | The patient owns three dogs, one of which is a new puppy; the dogs were fighting and the patient tried breaking them up. The dog bit the patient’s left thumb. Patient had wrapped kitchen tissue around the wound. | |

| PMHx | Diabetic – diet controlledAcid reflex | |

| FMHx | Unknown | |

| MHx | Omeprazole | |

| Allergies | Known None. | |

| SHx | Retired, lives with wife and three Jack Russell dogs. Currently staying in their holiday home. | |

| O/A | Patient drove himself in to the minor injuries unit (MIU) near his holiday home. Patient talking in full sentences, alert and GCS 15/15.

|

|

| O/E | ||

| RS |  RR at 18. SP02 98% (Air).Equal air entry. RR at 18. SP02 98% (Air).Equal air entry.

Equal rise and fall. Trachea central. Equal resonance throughout. Chest sounds: Clear. (Health References, 2012). |

|

| CVS | HR 64. BP 128/78. Cap Refill <2. | |

| CNS | Temp 36.5 | |

| ABDO | NAD | |

| LMS | Good radial pulse. Hands, fingers and thumb warm to touch. No loss of sensation. Left thumb swollen. Two half cm sized puncture wounds to left thenar eminence. Approximate 15ml of blood loss. Patient described the pain as throbbing. No boney tenderness on palpation and no pain or discomfort on movement. No loss of power or strength in hand or thumb and had full movement. Neurovascular intact. | |

| IMP/DD | Two half cm puncture wounds to left thumb. | |

| Rx |

|

|

| PLAN | Patient discharged. | |

Around 250, 000 people a year attend an emergency department because of a dog bite (Harding, 2014). A puncture wound is when an object pierces the skin and creates a small whole (Blasko, 2016), this is common in dog bites caused from penetration of the teeth (Wound Care Society, 2016). A dog bite contains a lot of bacteria which can cause serious infections if not treated correctly such as tetanus and rabies (NHS, 2016). Effective wound care is vital for the patient to encourage normal healthy healing and to prevent further complications such as infections (Bishop, 2015). Cleaning the wound thoroughly provides the foundation and preparation of normal healing and removes bacteria, debris and other foreign bodies (Wolcott and Fletcher, 2014). To clean the wound thoroughly, either running water or saline can be used to reduce infection risks and allow healing or wound closure (Wilkins and Unverdorben, 2013).

Griffiths, Fernandez and Ussia,(2001) found that using saline gave 6.1% of subjects an infection compared to 0% when using water. In a more detailed study Resende et al. (2015) found that tap water reduced gram-positive bacteria in wounds but there was no difference in between tap water and saline in other bacterias; haemolytic, gram-negative or fungi.

In acute and chronic wounds, there were no differences found between tap water and saline (Beam, 2006); however, in acute soft tissue wounds tap water reduced relative risks of infection by 45% (Paone, 2008). The Health Service Executive national guidelines for wound management (2009) believe that tap water is adequate irrigation for adults with lacerations, chronic wounds however, when using aseptic techniques during irrigation saline should be used at room temperature.

Interestingly, Ghaeminia et al.’s (2017) study suggests that using tap water to irrigate a surgical wound reduces the risk of inflammation and infections. Griffiths, Fernandez and Ussia. (2012) suggest there is no significant difference in using saline solution to tap water, although this study suggests that tap water does reduce infection. While, tap water is deemed to be safe when cleaning wounds when out in the community quality of tap water needs to be considered (Betts, 2003).

Weiss et al. (2012) argue that using saline or tap water has a very minimal impact on infection rates in wound care nevertheless, in this study less wound infections occurred with tap water therefore making it a safe and cost-effective alternative.

Water is more cost effective as it is cheaper than saline (British National Formulary, 2006). Tap water can be easily accessible and can be delivered at high water pressures and over a longer period of time and is therefore efficient wound irrigation can be provided at low costs (Bansal et al., 2002).

The use of tap water is common in the community, research suggests that tap water is an effective method that reduces infection risks when irrigating a wound (Griffiths, Fernandez and Ussia2001; Paone, 2008; Ghaeminia et al., 2017; Fernandez, Griffiths. and Ussia. 2012). When making the decision to use tap water instead of saline the quality, nature of the wounds and patient’s medical history should be taken into account (Fernandez and Griffiths, 2012); Griffiths, Ferndez and Ussia’s (2001) study suggests that patients prefer warm tap water over saline when irrigating their wounds.

References

- Bansal, B., Wiebe, R., Perkins, S. and Abramo, T. (2002). Tap water for irrigation of lacerations. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 20(5), pp.469-472. Available at: https://file:///C:/Users/Katy%20Ianson/Downloads/Tap_water_for_irrigation_of_lacerations.pdf (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Beam, J. (2006). Wound Cleansing: Water or Saline? National Center for Biotechnology Information, 41(2), pp.196-197. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1472650/ (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Betts, J. (2003). Review: wound cleansing with water does not differ from no cleansing or cleansing with other solutions for rates of wound infection or healing. Evidence-Based Nursing, 6(3), pp.81-81. Available at: https://ebn.bmj.com/content/6/3/81 (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Bishop, A. (2015). The importance of effective wound care. Adjacent Open Access. Available at: https://www.adjacentopenaccess.org/nhs-health-social-care-news/importance-effective-wound-care-2/15498/ (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Blasko, B. (2016). Puncture Wound Care, Treatment & Infection. eMedicineHealth. Available at: https://www.emedicinehealth.com/puncture_wound/article_em.htm (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- British National Formulary (2003). 45th edition. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; pp. 529–530.

- Fernandez, R., Griffiths, R. and Ussia, C. (2012). Water for wound cleansing. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 15(2), pp.135-136. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22336796 (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Ghaeminia, H., Hoppenreijs, T., Xi, T., Fennis, J., Maal, T., Bergé, S. and Meijer, G. (2016). Postoperative socket irrigation with drinking tap water reduces the risk of inflammatory complications following surgical removal of third molars: a multicentre randomized trial. Clinical Oral Investigations, 21(1), pp.71-83. Available at: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/pmc/articles/PMC5203820/ (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Griffiths, R., Fernandez, R. and Ussia, C. (2001). Is tap water a safe alternative to normal saline for wound irrigation in the community setting? Journal of Wound Care, 10(10), pp.407-411. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12964289 (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Harding, M. (2014). Dog and Cat Bites. Dog bite and cat bite infection information. Patient.info. Available at: https://patient.info/health/dog-and-cat-bites (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Health References (2012). Lungs. Available at: https://www.healthsanaz.com/lungs-drawing-for-kids-ldk08.html (Accessed: 30 Apr 2017).

- HSE. (2009). National best practice and evidence based guidelines for wound management. Available at: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/Primary/woundguidelines.pdf (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Nhs.uk. (2016). Animal and human bites – NHS Choices. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Bites-human-and-animal/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Paone. (2008) Does tap water decrease wound infection rates as compared to sterile saline? The Internet Journal of Academic Physician Assistants. 2008 Volume 6 Number 2.

- Resende, M., Rocha, C., Corrêa, N., Veiga, R., Passos, S., Novo, N., Juliano, Y. and Damasceno, C. (2015). Tap water versus sterile saline solution in the colonisation of skin wounds. International Wound Journal, 13(4), pp.526-530. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/iwj.12470/full (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Weiss, E., Oldham, G., Lin, M., Foster, T. and Quinn, J. (2013). Water is a safe and effective alternative to sterile normal saline for wound irrigation prior to suturing: a prospective, double-blind, randomised, and controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open, 3(1), p.e001504. Available at: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/1/e001504 (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Wilkins, G and Unverdorben, M, (2013) Wound cleaning and would healing: a concise review. Advances in skin and wound care 26(4) 160-163

- Wolcott, R. and Fletcher, J. (2014). The role of wound cleansing in the management of wounds. Wint journal. Available at: https://www.wintjournal.com/media/journals/_/1133/files/randall.pdf (Accessed 30 Apr. 2017).

- Wound Care Society. (2016). Dog puncture wound care in humans – Wound Care Society. Available at: https://woundcaresociety.org/dog-puncture-wound-care-humans (Accessed 31 Apr. 2017).

Plymouth University

Faculty of health and human sciences

School of health professionals

CASE STUDY FIVE

- Student ID: 10191190

- Word count: 502

- Submission date: Monday 8th May 2017

- Module code: Para 301

- Module title: Refining practitioner skills for patient care

- Incident Details: 4 year old male, mum brought her son into minor injuries unit.

Case Study Five – Evaluation of antipyretics in children with a fever.

| PC | Unwell, rubbing his right ear and a high temperature. | |

| HxPC | The patient has a 4 day history of cough and cold symptoms. No vomiting or diarrhoea. The patient hasn’t been in contact with anyone that has been poorly. The patient is off food and sipping water throughout the day. He had is bowels open 24 hours ago which was normal and still passing urine okay. The patient has not been abroad or been swimming recently. Mum hasn’t given him any Calpol today. | |

| PMHx | None.Vaccinations (Measles, mumps and rubella) are up to date. | |

| FMHx | Mum suffers from asthma. | |

| MHx | None | |

| Allergies | None Known | |

| SHx | Patient has a family unit. The patient is not known to social services and goes to school locally. Smoke free house. | |

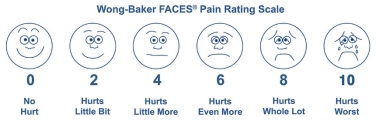

| O/A | The patient seemed quiet and clingy with mum. GCS 15, (A) VPU. Using the wong- baker face pain score for children, the patient scored 8/10.

(Wong-Baker FACES Foundation, 2017) |

|

| O/E | ||

| RS |  RR 28SP02 99% (Air) RR 28SP02 99% (Air)

Trachea central. Equal resonance throughout. No tracheal tug present. No respiratory recession. Not cyanosed. Patient was not using accessory muscles. Chest sounds clear, equal rise and fall. (Health References, 2012). |

|

| CVS | Cap refill 3.HR 135 | |

| CNS | Temp 38.8PEARL 3mm

No photophobia |

|

| ABDO | Look: Patient’s abdomen is not distended, no rashes, red marks or bruising. No scars seen.Listen: Normal bowel sounds.

Percuss: Normal percussion sounds. Palpate: Soft abdomen, no guarding, no pain or discomfort, no masses. Patient off food but still sipping water throughout the day. Opened bowel 24 hours ago. Passing urine as normal. |

|

| LMS | NAD | |

| OTHER | No rashes or mottled skin. Peripheries warm to touch. No headaches, not photophobic.Ears:

Look: Outer ears – normal, no swelling, redness or discharge. Palpate: Mastoid – no pain. Tragus – no pain. Pulled on the pinna – No pain. Look in external auditory canal: Pink in colour, no discharge and no swelling. Look in tympanic membrane: Bulging, dull, red edges and fluid visible. No perforations.

(National Institute of Deafness Children and Other Communication Disorders, (NIDCD) 2017)

Nose: Green discharge. Throat: Dry mouth and tongue. Generally red throat. Straight uvela. Tonsils equally raised on both sides, No pits and puss.

Glands:Tonsilia glands raised. No other Lyadenoplymphadanophathy. |

|

| IMP/DD | Otitis media – middle ear infection. | |

| Rx |

|

|

| PLAN | To keep the patient’s fluids up. Give the patient regular Calpol and Nurofen. Advise mum to keep the patient’s ears dry. Safety netting in place: mum will be staying at home with the patient to look after him and will keep him off school for a day (Friday) so he has the whole weekend to rest and recover. Worsening advice given to call 111 if worried. | |

The most common bacterial ear infection in children, more than in adults, is otitis media (NIDCD, 2017). This is a very painful middle ear infection with swelling and fluid behind the eardrum (Laflamme, 2016). Symptoms of an ear infections in children are: painful ears, rubbing ears, broken sleep, crying, quiet or clingy, hearing and balance is affected, a fever of 38 degrees or higher, and loss of appetite (Mayo Clinic, 2016). Infections cause fever, which is classed as a temperature of 38 degrees or above (NHS, 2015).

Graneto (2016) believes that 20% of children visit the emergency department due to having a fever. The body’s natural immune system response is to raise the temperature to direct white blood cells to fight the infection (Klaff, 2009). A child should only receive antipyretic medication if severely affected; high temp of 40 degrees or higher, taking little fluid, are in shock, chronic heart or lung disease, and stroke patients (Niehues, 2013). Lava et al’s (2012) study found that children are often prescribed antipyretics for discomfort that frequently is accompanied by a fever. In England, antipyretics are only used when the fever is causing harm to the patient such as sepsis and the patient is in distress (Martin, 2016).

Sarrell, Wielunsky and Cohen’s (2006) study found that the use of antipyretics to reduce fever and make the child more comfortable with a temperature of 38.4 and over to be beneficial and safe. Ravanipour, Akaberian and Hatami (2014) found that parents would give antipyretics to children because they were worried about adverse effects of a fever causing damage. Hays et al, (2008) found the use paracetamol and ibuprofen together to decrease fever in children aged between 6 months to 6 years with a temperature of 37.8 and up to 41 degrees worked effectively and quickly. Sullivan and Farrar (2011) agrees that the use of antipyretics in a fever should be to improve a child’s comfort and not to normalise their body temperature. Fevers are self-limiting although it is unpleasant it is deemed as a naturally helpful defence (Gardner, 2012).

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2013) does not recommend using antipyretics such as Calpol to solely reduce a children’s temperature. The South Western Ambulance Service Trust guidelines (2014) are to only consider Calpol or Nurofen if the child seems to be distressed and should not be used to decrease the body temperature or stop febrile convulsions.

In conclusion, studies such as Ullman (2009), NHS, (2016) and Doyle and Schortgen (2016) suggest that children’s fevers, generally up to 38 degrees are better treated without antipyretics such as Calpol and Nurofen. The role of the fever plays an important role in enabling host defence stimulating immunomodulatory molecules and immunity cells (Meng, 2004) and is deemed beneficial by protecting the child El-Radhi, 2012). However, antipyretics can be administered if child is in distress or pain due to the fever (Schortgen, 2012) or if they have a severe cardiovascular, respiratory or neurological impairments or disease, very poorly; septic (Outzen, 2009).

References

- Bartlett, D. (2017). Fever: Evidence Based Practice. Ceufast.com. Available at: https://ceufast.com/course/fever-evidence-based-practice (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Doyle, J.F., Schortgen. F. (2016). Should we treat pyrexia? And how do we do it? Crit Care, 3, 20 (1), 303.

- El-Radhi, S. (2012). Fever management: Evidence vs current practice. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 1(4), pp.29-33. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4145646/ (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Gardner, J. (2012). Is fever after infection part of the illness or part of the cure? Emerg Nurse, 19 (10), 20-25.

- Graneto, J. (2016). Emergent Management of Pediatrics Patients with Fever: Overview, Patient History, the Physical Exam. Emedicine.medscape.com. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/801598-overview#a1 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Hay, A., Costelloe, C., Redmond, N., Montgomery, A., Fletcher, M., Hollinghurst, S. and Peters, T. (2008). Paracetamol plus ibuprofen for the treatment of fever in children (PITCH): randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 337(sep02 2), pp.a1302-a1302. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/337/bmj.a1302.full (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Health References (2012). Lungs. Available at: https://www.healthsanaz.com/lungs-drawing-for-kids-ldk08.html (Accessed: 1 May 2017).

- Klaff, L. (2009). Fever Fears: A Guide for Treating Fever in Children. Parents. Available at: https://www.parents.com/health/fever/fever-fears-a-guide-for-treating-fever-in-children/ (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Laflamme, M. (2016). Acute Otitis Media. Healthline. Available at: https://www.healthline.com/health/ear-infection-acute (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Lava, S., Simonetti, G., Ramelli, G., Tschumi, S. and Bianchetti, M. (2012). Symptomatic Management of Fever by Swiss Board-Certified Paediatricians: Results from a Cross-Sectional, Web-Based Survey. Clinical Therapeutics, 34(1), pp.250-256. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22218087 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Martin, D. (2016). Fever: Views in Anthroposophic Medicine and Their Scientific Validity. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2016, pp.1-13. Available at: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2016/3642659/ (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Mayo Clinic. (2016). Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ear-infections/symptoms-causes/dxc-20199484 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Meng, D. (2017). Fever: the long and short of it. National University Hospital. Available at: https://www.nuh.com.sg/wbn/slot/u3609/Education/Healthcare%20Professionals/Education%20&%20Training%20Opportunities/Bulletin/bulletin_41.pdf (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- National Institute of Deafness Children and Other Communication Disorders. (2017). Ear Infections in Children. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/ear-infections-children (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- NHS (2016). Fever in children – NHS Choices. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/feverchildren/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- NHS. (2015).What is a fever (high temperature) in children? – NHS Choices. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/chq/pages/1633.aspx?categoryid=62&subcategoryid=64 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- NICE (2013). Do not use antipyretic agents with the sole aim of reducing body temperature in children with fever. NICE. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/donotdo/do-not-use-antipyretic-agents-with-the-sole-aim-of-reducing-body-temperaturein-children-with-fever (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Niehues, T. (2013). The Febrile Child: Diagnosis and Treatment. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 110(45), pp.764–774. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3849992/ (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Outzen, M. (2009) Management of fever in older adults. Journal of Erotological Nursing. 35, 5, 17-23

- Ravanipour, M., Akaberian, S. and Hatami, G. (2014). Mothers’ perceptions of fever in children. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 3(97). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4165093/ (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Sarrell, E., Wielunsky, E. and Cohen, H. (2006). Antipyretic Treatment in Young Children with Fever. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(2), p.197. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/204526 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Schortgen, F. (2012). Fever in Sepsis. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 78(11), pp.1254-64. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22772856 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- South Western Ambulance Service Trust (SWAST) (2014) Paediatric Fever, Available at: https://www.swast.nhs.uk/Downloads/Clinical%20Guidelines%20SWASFT%20staff/CG16_Paediatric_Fever.pdf (Accessed: 1st May 2017).

- Sullivan, J. and Farrar, H. (2011). Fever and Antipyretic Use in Children. Pediatrics, 127(3), pp.580-587. Available at: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2011/02/28/peds.2010-3852 (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Ullman, D. (2017). Epidemic of Fever Phobia: The Facts on Why Fever Is Your Friend. The Huffington Post. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/dana-ullman/epidemic-of-fever-phobia_b_305615.html (Accessed 1 May 2017).

- Wong-Baker FACES Foundation (2017) Pain Rating Scale. Available at: https://wongbakerfaces.org/ (Accessed: 1 May 2017)

Plymouth University

Faculty of health and human sciences

School of health professionals

CASE STUDY SIX

Student ID: 10191190

Word count: 533

Submission date: Monday 8th May 2017

Module code: Para 301

Module title: Refining practitioner skills for patient care

Incident Details: 38 year old women with an inversion ankle injury.

Case study three – Evaluation of mobilisation or immobilisation in ligament ankle injuries.

| PC | Left ankle injury | |

| HxPC | The patient was out running early this morning when she slipped on gravel and twisted her left ankle. The patient then had to walk a mile back home. When the patient got home there was sudden onset of pain and swelling to outer ankle. The patient found it very painful to weight bear. The patient was wearing running trainers at the time of the incident. The patient lives a very active life, loves running, swimming and going to the gym. The patient took 1g paracetamol and 400mg ibuprofen at 7 30am this morning. | |

| PMHx | None. Normal fit and well. Lives a very active lifestyle. | |

| FMHx | NAD | |

| MHx | None. | |

| Allergies | None known. | |

| SHx | Lives with husband and 14 year old daughter. Patient’s occupation is a waitress. | |

| O/A | Patient walked in to the minor injuries unit limping and walking on her toes, not putting her heel down. GCS 15, (A) VPU. Patient gave the pain a score of 7/10. Talking in full sentences. | |

| O/E | ||

| RS |  RR 16SP02% 99 (Air) RR 16SP02% 99 (Air)

Equal rise and fall. Trachea central. Equal resonance throughout. Chest sounds: Clear. (Health References, 2012). |

|

| CVS | Cap refill central <2HR 58

BP 118/64 |

|

| CNS | Temp 36.6 | |

| ABDO | NAD | |

| LMS | Patient denies any pain or discomfort anywhere else. No other injuries found, no pain or discomfort in right leg, both arms, neck and back.Look: Swelling ++ to lateral malleolus, no obvious gross deformity noted. Definite globalised bruising around ankle.

Palpate: Painful ++ over lateral malleolus. No pain over knee, lower leg, medial malleolus, tarsals, metatarsal or toes. Ligaments clinically intact. No pain or discomfort in calf on palpation. Achilles clinically intact and no pain or discomfort. No loss of sensation. Good pedal pulse. Well perfused, cap refill <2.

Movement: Patient is unable to weight bear fully, limping. Active: Reduced dorsiflexion / planter flexion, query due to swelling. Patient unable to do Inversion and eversion as it is painful and swollen. Resistance: Did not attempt to do resisted movement due to the paint being into much pain and Ottawa positive Left ankle – x-ray required, so could do more damage.

(American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2017) |

| Investigation | X-ray done. No bony injury seen. |

| IMP/DD | Ligament sprain / strain |

| Rx |

|

| PLAN | Patient advised to take regular paracetamol and ibuprofen. Advised for elevation, ice, analgesia and no running for 2 weeks. |

Clinicians in primary care and accident and emergency (A&E) settings see a lot of ankle injuries, commonly inversion and plantar flexion injuries (Lowth, 2016). Sprains and strains are common sporting injuries that affect ligaments and muscles supporting the ankle joint (NHS, 2016). Ankle injuries, from fractures to ligament and muscle injuries, account for over 1 million A&E admissions every year (Core, 2017).

The first 48 – 72 hours of a sprain or strain injury requires Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation to aid the recovery process (Allen, 2017). Lamb et al. (2009) found that patients who wore tubular compression bandages made a slower recovery than patients who wore a below-knee cast or Air cast for a short period of time. Watts and Armstrong (2001) found that double tubigrip in mild-moderate ankle sprains does not speed up recovery time and patients found they needed more analgesia to manage the injury when wearing the double tubigrip. However, Ogilvie-Harris and Gilbart (1995) found that patients had a quicker recovery when taking nonsteroidal anti-flammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and chose to actively mobilise the ankle injury.

Another study by Boyce, Quigley and Campbell (2005) found that using the air cast for short periods of time between 10 days and a month made significant improvements to the ankle injury and function. Although elastic bandage is the preferred choice and has less complications than tape, recovery time was longer than those in a semi-rigid ankle support (Kerkhoff et al, 2002). Patients found that lace-up ankle supports were for beneficial for reducing swelling, patient satisfaction, less complications compared to semi-rigid ankle supports, elastic bandages or tape although no significant difference was found in ankle function results and pain management (Lardenoye et al, 2012).

Ardèvol et al. (2002) found when treating an ankle injury immobilisation takes longer for patients to recover; however, functional treatment is faster and deemed safe. Karlsson et al. (2007) compared early mobilisation versus the air cast in chronic lateral ligament damage and found that function and stability did not differ in the two methods of treatment; however, plantar flexion strength returned quicker, and laxity complications were reduced in early mobilisation treatment safely. Conversely, Petersen et al. (2013) found that using a below knee cast for 10 days can reduce swelling and pain whilst the ligament is in the early healing stage.

Treating ligament ankle injuries with NSAIDs is really beneficial to the patient’s pain management and recovery (Paoloni et al, 2009). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) guidelines for managing sprains and strains is to take and keep on top of paracetamol and NSAIDs for at least 48 hours, and to use the Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation measure (PRICE); this includes using simple elastic bandages or elastic tubigrip bandage to help reduce swelling and support the ankle injury. According to South Western Ambulance Service (2017) minor sprains can be treated at home in accordance to NICE guidelines’ (2016) PRICE and encouraged to move the ankle if not too painful. Early mobilisation and NSAIDs are deemed to be the best methods for quicker recovery time and allows full function back to the injured ankle although, patients should be assessed on an individual basis (Doherty et al, 2016).

References

- Allen, B. (2017). Torn Ankle Ligaments. University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Available at: https://uihc.org/health-library/torn-ankle-ligaments (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Aofas.org. (2017). How to Care for a Sprained Ankle. Available at: https://www.aofas.org/footcaremd/how-to/foot-injury/Pages/How%20to%20Care%20for%20a%20Sprained%20Ankle.aspx (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Ardèvol, J., Bolíbar, I., Belda, V. and Argilaga, S. (2002). Treatment of complete rupture of the lateral ligaments of the ankle: a randomized clinical trial comparing cast immobilization with functional treatment. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 10(6), pp.371-377. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00167-002-0308-9?LI=true (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Boyce, S., Quigley, M. and Campbell, S. (2005). Management of ankle sprains: a randomised controlled trial of the treatment of inversion injuries using an elastic support bandage or an Air cast ankle brace. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(2), pp.91-96. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1725120/pdf/v039p00091.pdf (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Core, M. (2017). Different Types of Ankle Injuries. Ossur.co.uk. Available at: https://www.ossur.co.uk/about-ossur/news-from-ossur/172-different-types-of-ankle-injuries (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Doherty, C., Bleakley, C., Delahunt, E. and Holden, S. (2016). Treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent ankle sprain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(2), pp.113-125. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308955353_Treatment_and_prevention_of_acute_and_recurrent_ankle_sprain_An_overview_of_systematic_reviews_with_meta-analysis (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Health References (2012). Lungs. Available at: https://www.healthsanaz.com/lungs-drawing-for-kids-ldk08.html (Accessed: 3 May 2017).

- Karlsson, J., Lundin, O., Lind, K. and Styf, J. (2007). Early mobilization versus immobilization after ankle ligament stabilization. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 9(5), pp.299-303. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10512212 (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Struijs PAA, Marti RK, Assendelft WJJ, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. (2002) Different functional treatment strategies for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD002938. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002938.

- Lamb, S., Marsh, J., Hutton, J., Nakash, R. and Cooke, M. (2009). Mechanical supports for acute, severe ankle sprain: a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 373(9663), pp.575-581. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736 (09)60206-3/fulltext (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Lardenoye, S., Theunissen, E., Cleffken, B., Brink, P., de Bie, R. and Poeze, M. (2012). The effect of taping versus semi-rigid bracing on patient outcome and satisfaction in ankle sprains: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 13(1). Available at: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-13-81 (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Lowth, M. (2016). Ankle Injuries. Sprained ankle and ankle injuries treatment. Patient.info. Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/ankle-injuries-pro (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016). Sprains and strains – NICE CKS. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- NHS (2016). Sprains and Strains – NHS Choices. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Sprains/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in sports medicine: guidelines for practical but sensible use British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009; 43:863-865.

- Ogilvie-Harris, D. and Gilbart, M. (1995). Treatment Modalities for Soft Tissue Injuries of the Ankle. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 5(3), pp.175-186. Available at: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/pubmed/7670974?access_num=7670974&link_type=MED&dopt=Abstract (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Paoloni, J., Milne, C., Orchard, J. and Hamilton, B. (2009). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in sports medicine: guidelines for practical but sensible use. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(11), pp.863-865. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19546098 (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- Petersen, W., Rembitzki, I., Koppenburg, A., Ellermann, A., Liebau, C., Brüggemann, G. and Best, R. (2013). Treatment of acute ankle ligament injuries: a systematic review. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 133(8), pp.1129-1141. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00402-013-1742-5 (Accessed 3 May 2017).

- South Western Ambulance Service Trust (SWAST) (2017) Self Care, Available at: https://www.swast.nhs.uk/self-care.htm (Accessed: 3rd May 2017).

- Watts BL, Armstrong B A randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of double Tubigrip in grade 1 and 2 (mild to moderate) ankle sprains Emergency Medicine Journal 2001;18:46-50.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this assignment and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal (Docpods, 2017)

(Docpods, 2017)