Effect of Supply Chain Relationships on Food Waste Management

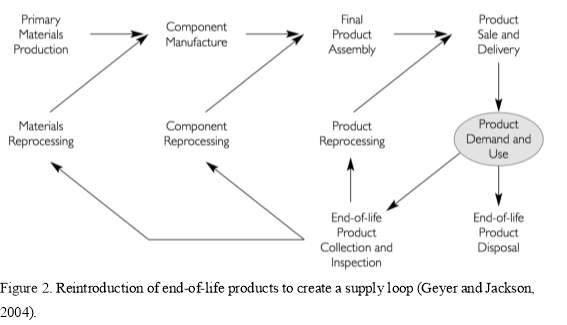

Info: 9953 words (40 pages) Dissertation

Published: 25th Aug 2021

Tagged: Supply ChainSustainability

Chapter 1

1.1 Introduction

This study aims to understand how supply chain relationships can contribute to food waste management within the Circular Economy (CE) framework. Food waste management is well established in sustainability literature; however, there has not been an investigation into how collaborating with supply chain stakeholders can support its management in the CE framework. This chapter will summarise food waste and implications for its management within the CE, followed by a justification for this research. Lastly, the research question, aim and objectives are presented, along with a research structure.

1.2 Research background

1.2.1 Food waste

The unsustainability of current food systems, as underpinned by linear economic development models, is a growing issue in today’s society. Wasting food is not only economically inefficient, but also environmentally and socially damaging, with rising greenhouse gases (FAO, 2017), depletion of natural resources, such as water and energy (Darlington, 2009), and food insecurity, becoming increasing concerns (Jurgilevich et al., 2016; WRAP, 2017). According to WRAP (2017), 7.3 million tonnes of food and drink were wasted in 2015 in UK households, representing a 4.4% increase compared to 2012 figures; avoidable food waste represents 60.2% of that figure. Globally, roughly one-third, or 1.3 billion tonnes, of food is wasted (FAO, 2017). The FAO estimates that if one-fourth of global food waste or loss was saved, it could feed 870 million hungry people.

Consequently, food waste management has received attention from various scholars, including Darlington (2009), Batista et al., (2015), Jurgilevich et al., (2016), Papargyropoulou et al., (2014), and Sert et al., (2014). These studies have identified the causes for food waste and the preferred methods for managing it.

1.2.2 Food waste management in the Circular Economy

Despite receiving greater attention, the increasing food waste figures point to the complexity of the problem, requiring extensive research into this multi-faceted issue. As one of the largest industrial sectors in the world (Batista et al., 2015), the food industry needs to be comprehensively examined. Following the increasing interest CE has gained as a model of sustainable economic development (Lieder and Rashid, 2016; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Genovese et al., 2017) academics have evidenced the framework’s applicability to food systems (Jurgilevich et al., 2016; Laso et al., 2016). Moreover, the solutions presented in the studies show that extensive engagement with different stakeholders is required at each stage to achieve a more sustainable food system. Particularly, in attempting to reduce waste, more government involvement is needed in supporting and implementing policies; additionally, customer and retailer expectations need to be managed to prevent food waste (Jurgilevich et al., 2016). These concerns are supported by the World Economic Forum; Albrectsen (2017) discusses the importance of finding “common ground” and not being afraid “to take risks to collaborate in new ways”.

1.3 Research justification

This complex background, and the lack of studies explicitly addressing the importance of collaborative relationships in sustainability settings, validate the need to gain a greater understanding of how supply chain relationships can assist the management of food waste within the CE framework. To fill this gap, this study examines how farmers currently manage their waste, and how they engage with supply chain members to support this. The data will be collected through semi-structured interviews and will be thematically analysed to gain in-depth insight into the collaborative relationships formed to tackle food waste, thus addressing the research objectives.

1.4 Research structure

Chapter 2: Literature review

2.1 Introduction

This chapter examines the body of literature concerned with sustainability in supply chains. It includes an overview of sustainable supply chain management, and investigates the role of collaborative relationships in the context of Industrial Ecology, Industrial Symbiosis, and Closed-Loop Supply Chains. These are used to understand the implications of collaborative supply chain relationships on food waste management in the context of the Circular Economy.

2.2 An overview of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM)

SSCM has been extensively discussed within the literature (Carter and Rogers, 2008; Pagell and Wu, 2009; Gupta et al., 2013). It considers factors other than profit-maximisation through efficient resource allocation, and thus cost reductions. Hence, in economic terms, traditional supply chain management has mirrored linear economics in its primary concern with efficient resource allocation, which fails to account for the finite nature of resources (Ghisellini et al., 2016).

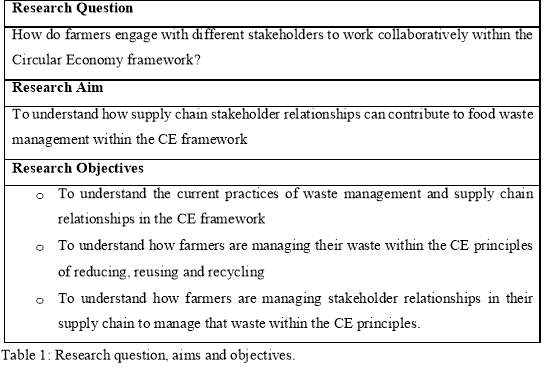

Given increasing stakeholder pressure as a result of supply chains’ exploitation of natural resources, these shifted from purely economic concerns towards greener environmental practices. However, as supply chains also utilise human capital (Gupta et al., 2013), they encompass social concerns as well as economic and environmental ones. Thus, SSCM encapsulates economic (profit-maximising), social (local communities’ quality of life) and environmental (sustainable usage of natural resources) interests. Hence, SSCM aims to simultaneously maximise performance of all three dimensions, which is consistent with Elkington’s (1998) triple bottom line concept, argued to create competitive advantage over firms only attempting to maximise performance of one or two dimensions (Figure 1).

The three-dimensional sustainable supply chain provides an overview of the goals a firm must pursue simultaneously to derive the greatest competitive advantage. However, it fails to address which and how different factors may affect the pursuit of such goals. Moreover, it propagates the pursuit of sustainable microeconomic performance as opposed to sustainable macroeconomic development. Consequently, an investigation into different sustainability models is required to address these concerns.

2.3 Supply chain relationships in Industrial Ecology (IE)

IE considers the efficiency of interactions between industrial ecosystems aiming at closing loops by using waste as a resource (Lombardi and Laybourn, 2012; Leigh and Li, 2015), “eliminating the notion of an undesirable by-product” (EMC, 2013, pp.27). In attempting to achieve a closed-loop with the lowest environmental impact, extant literature has focused on geographically bound industrial systems (Ehrenfeld and Gertler, 1997; Seuring, 2004), reuse and recycling of materials (Geyer and Jackson, 2004; Jacobsen, 2006) and superior competitiveness (Esty and Porter, 1998).

A prerequisite for the formation of viable IE networks is having industrial systems which are geographically bound (Seuring, 2004). However, Lombardi and Laybourn (2012) and Leigh and Li (2015) argue that as IE evolves, the need for geographic proximity is less evident; this lessens the importance given to geographic boundaries, expanding possibilities for firms, previously seen as separate entities (Leigh and Li, 2015), to work collaboratively towards more effective waste management (Chertow and Ehrenfeld, 2012). In considering a cyclical model where no negative impact is observed (Chertow, 2000), scholars argue that loop closing can be achieved at different supply chain stages (Leigh and Li, 2015). A focus on each stage is critical in facilitating the management of relationships necessary to achieve closed-loops. As such, Bansal and McKnight (2009) point to the key role collaboration plays in achieving a closed-loop resource flow, which differentiates IE from Industrial Symbiosis (IS). Thus, IS introduces the collaborative dimension previously neglected in IE literature.

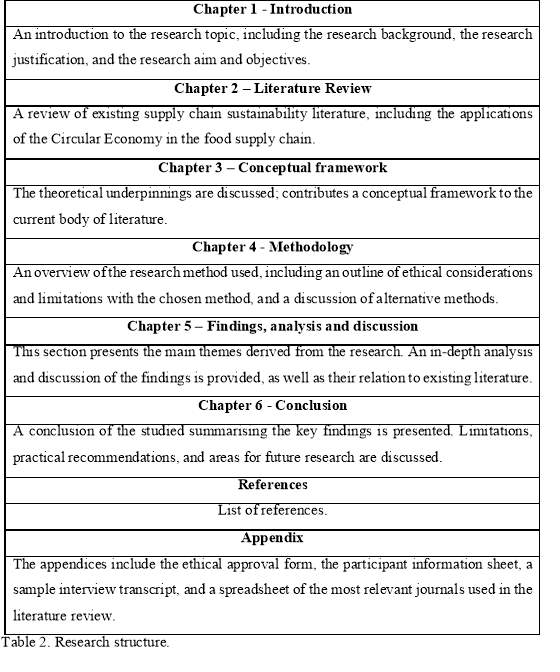

Furthermore, the focus on the reuse and recycling of materials in various industries has overlooked the importance of waste prevention (Leigh and Li, 2015). In investigating supply chain loops, scholars have examined the viability of reintroducing end-of-life products (Figure 2).

Furthermore, the focus on the reuse and recycling of materials in various industries has overlooked the importance of waste prevention (Leigh and Li, 2015). In investigating supply chain loops, scholars have examined the viability of reintroducing end-of-life products (Figure 2).

However, clear limitations are present with focusing solely on reuse and recycle. Geyer and Jackson (2004) highlight issues such as limited access to end-of-life products which can be reintroduced to the supply chain, limited demand for remanufactured products, and limited feasibility of reprocessing end-of-life products. These constraints can be managed through waste prevention, a key component of the CE framework (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Jurgilevich et al., 2016), by reducing the amount of materials that need to be reintroduced to the loop and the need for a market for remanufactured products. Secondly, access to end-of-life products can be facilitated by developing intra-firm relationships, allowing end-of-life products from one supply chain member to be reintroduced elsewhere. Hence, IE literature has neglected waste prevention (Leigh and Li, 2015) and the supply chain relationships necessary to develop industrial ecosystems (Chertow and Ehrenfeld, 2012).

2.4 Supply chain relationships in Industrial Symbiosis (IS)

Within the field of IE, IS presents tangible actors concerned with the utilization of by-products, materials, water and/or energy as inputs at a given point in a supply chain (Chertow, 2007; Posch, 2010; Boons et al., 2011). Central to the concept of IS is the opportunity of creating sustainable competitive advantage through the creation of synergistic collaborations, resulting in decreased costs and better environmental performance (Yuan and Shi, 2009; Yu et al., 2013). However, research suggests that geographical boundaries are also critical in establishing IS in industrial systems due to easier access to resources being reincorporated into a supply chain, enabling collaborative relationships to form (Chertow, 2007; Porsch, 2010). Although the importance of geographical boundaries is still recognized in IS literature (Chertow and Ehrenfeld, 2012), recent research has shifted its priority, focusing instead on the development of supply chain relationships to achieve sustainability (Bansal and McKnight; 2009; Lombardi and Laybourn 2012; Leigh and Li, 2015).

In studying the development of such relationships, Korhonen and Snäkin (2005) found that possibilities for collaboration are positively linked to increased levels of diversity among collaborating stakeholders in the evolution of an industrial park. However, they argue that introducing too many actors may hinder possibilities for collaboration and interdependence. Nonetheless, the study does not state an optimal level of stakeholder diversity for achieving efficient collaboration, nor does it consider how variables such as industry type, level of industry competition, and cultural norms, among others, may impact collaboration. Arguably, a high level of collaborating actors within an industrial system may present more opportunities for relevant knowledge to be shared. Mirata and Emtairah (2005) highlight the formation of industrial symbiosis networks as a tool for encouraging environmental innovation, achieved through collectively addressing common problems and “promoting a culture of inter-organisational collaboration oriented towards environmental challenges” (Boons et al., 2011, pp.906). Posch (2010) reiterates this by defining sustainable development as a direct outcome of relationships guided by sustainability-oriented interactions. Hence, collaboration must be broad and diverse to enable achievement of a culture of sustainability amongst firms.

However, critical to forming collaborative relationships which aim for sustainability in supply chains is the need for the creation and dissemination of key knowledge (Leigh and Li, 2015), which IS literature fails to address.

2.5 Collaboration and closed-loop supply chains (CLSCs)

Guide and Van Wassenhove (2009) define CLSCs as maximizing value creation throughout the entirety of the supply chain, recovering value from materials over time. With this in mind, scholars have highlighted the importance of not only limiting the damaging impact on natural resources, but also creating value (Krikke et al., 2013), as well as establishing collaborative relationships to create such value (Sarkis et al., 2011; Bell et al., 2013; Matopoulos et al., 2015). However, focus is given to the impact of collaborative relationships on supply chain performance in terms of the economic value that can be derived from CLSCs (Guide and Van Wassenhove, 2009; Kumar and Banerjee, 2012; Bell et al., 2013), neglecting the integration of sustainability issues into it (Miemczyk et al., 2016).

With a focus on economic performance rather than loop-closing, Kumar and Banerjee (2012) examined specific activities and their importance to collaboration. The findings of the study are congruent with extant literature, highlighting the need for sharing knowledge (Leeuw and Fransoo, 2009) and mutuality of interests (Abreu et al., 2009) for effective supply chain collaboration. Nonetheless, Kumar and Banerjee’s (2012) research methodology presents limitations which could have impacted the results. While the methodology accurately reflects the study’s aim by using a multi-industry sample, investigating a specific industry would have given an in-depth understanding of the framework’s applications in a specified context. This is observed in Miemczyk et al.’s(2016) study, which closely examined two case studies within similar industries (commercial carpets and composite textiles) to ensure consistency of results, thus generating “rich insights into CLSCs” (Miemczyk et al., 2016, pp.457). Hence, further research into the framework’s micro-level applicability in different industries is warranted. Moreover, using an online-based survey allowed data to be gathered in various locations (Kumar and Banerjee, 2012); however, the study exclusively investigated industries in India, possibly limiting a truly broad understanding of collaboration. Although results may be generalizable given the multi-industry sample, country-specific factors such as culture, may play a role in the legitimacy of results. Consequently, the study lacks external validity and further research into industries in different countries is needed to validate the framework.

Moreover, despite Kumar and Banerjee’s (2012) study introducing the knowledge-sharing component of collaborative relationships previously lacking from IE and IS literature, the focus is on the improved economic performance which can be derived from this. Hence, a sustainability perspective and a framework for this is still lacking.

2.6 Supply chain management in the CE framework

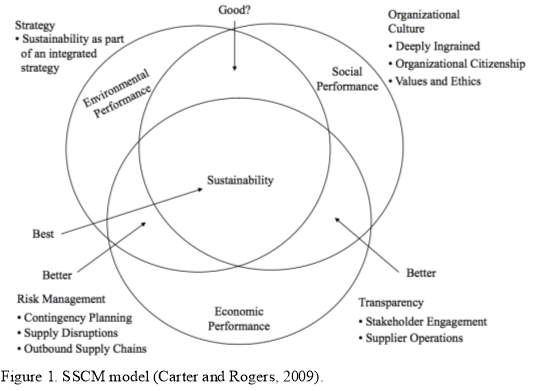

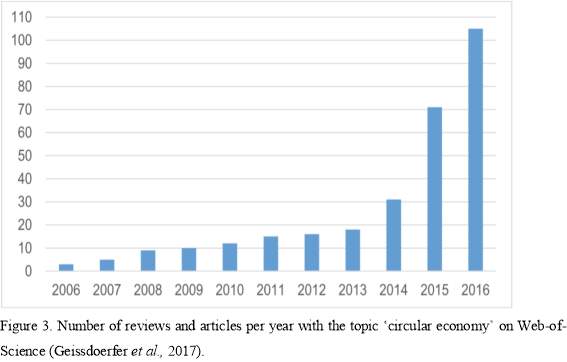

The Circular Economy is “an industrial economy that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design” (EMC, 2013, pp.07). The concept of CE has gained increasing attention (Figure 3) following Boulding’s (1966) description of the Earth as a closed system whereby the economy and the environment must “coexist in equilibrium” (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017, pp. 759).

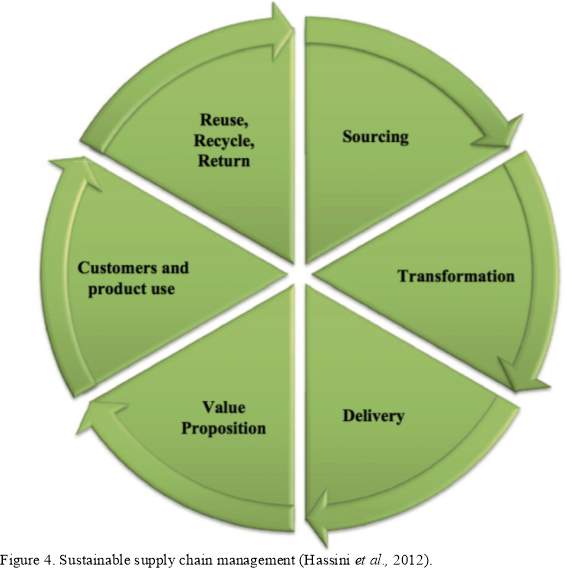

In attempting to achieve a “closed sphere of human activity” (Boulding, 1966, pp.01), three activities have been deemed essential: reducing, reusing, and recycling (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Jurgilevich et al., 2016; Winans et al., 2017) – the 3Rs. However, some scholars extend these to include repair, remanufacturing, refurbishing, long-lasting design, and maintenance (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). From these activities, it is clear to see the general applications of CE have focused on the manufacturing and construction industries (Lieder and Rashid, 2016; Nasir et al., 2016) and its mathematical modelling (George et al., 2015; Genovese et al., 2017). Particularly, Hassini et al., (2012) analysed the viability of material recycling as part of a six-factor supply chain wheel (Figure 4).

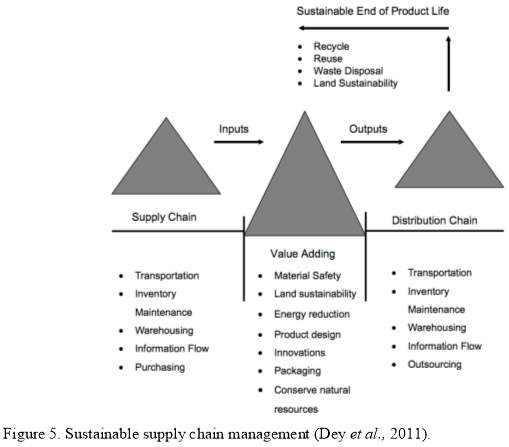

Hassini et al.’s(2012) vision of sustainable supply chains incorporates ‘reuse’ into a recycling function and neglects the reduction of waste altogether. Similarly, Dey et al. (2011) incorporate reuse and recycle into an ‘end of product lifecycle’ measure (Figure 5), as an afterthought rather than as a process to be incorporated throughout all the supply chain stages.

These models place greater emphasis on the recycling of materials than is traditionally observed in literature (Jurgilevich et al., 2016; Ghisellini, et al., 2016), which sees reuse and recycle as remedial actions to waste generation. As such, the resource-efficiency nature of waste reduction ensures the greatest economic, environmental and social benefits are achieved (Ghisellini et al., 2016), and thus deserves greater attention from scholars.

Nonetheless, the nature of the food industry lends itself to the seamless application of waste reduction strategies. This highlights the importance of investigating specific industries to gain in-depth understanding of the micro-level applicability of sustainability models, consistent with Miemczyk et al.’s(2016) investigation of CLSCs within similar industries for data consistency.

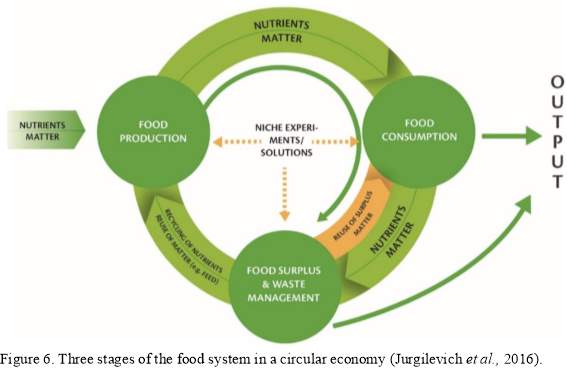

2.6.1 CE principles and food supply chain applications

The main CE principles (3Rs) have significant applicability to the food industry, appropriately highlighting the waste reduction principle previously overlooked in literature’s investigation of other supply chains in the CE context. In the food system, CE principles apply to the reduction in the amount of waste generated, reuse of food through redistribution channels, nutrient recycling, and by-product utilisation (Jurgilevich et al., 2016). In conceptualising a circular food supply chain, Jurgilevich et al., (2016) highlight the criticality of implementing the 3Rs at every stage of the supply chain (Figure 6).

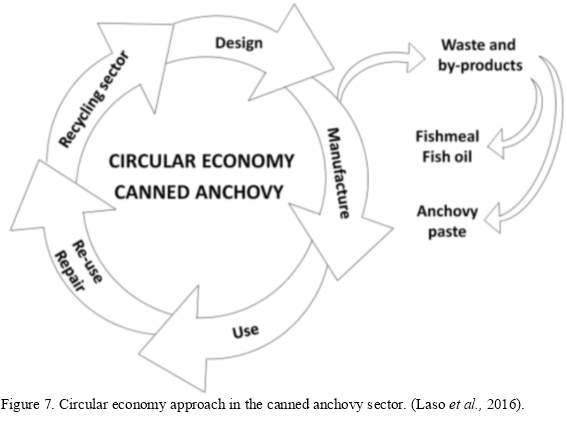

Laso et al., (2016) use a similar model (Figure 7) demonstrating the opportunities for applying CE in the canned anchovy industry. Hence, the model provides opportunities for wider applications to varying food supply chains; however, this is still lacking in current literature.

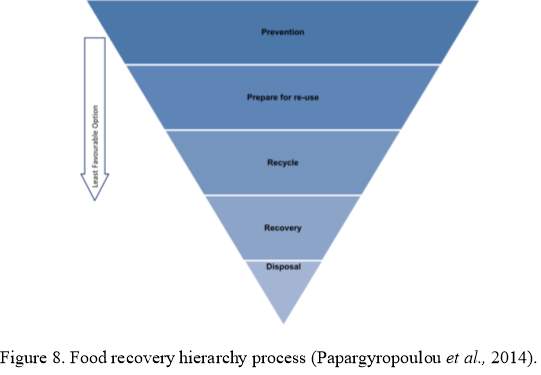

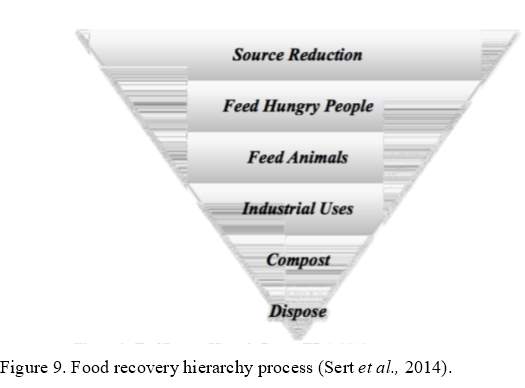

Moreover, a disconnect between the CE supply chain applications and a desirable hierarchy of activities in food systems is observed. Papargyropoulou et al., (2014) and Sert et al., (2014) argue that successfully tackling food waste requires a structured approach with specific activities ranked from most to least desirable. The scholars’ pyramids (Figures 8 and 9) show models consistent with the CE hierarchy identified in literature (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Jurgilevich et al., 2016).

However, Papargyropoulou et al., (2014) and Sert et al. (2014) fail to link this to the CE framework despite clear similarities between the concepts, causing a disjointed approach to finding a solution for current inefficiencies.

Furthermore, the importance of collaboration, which gained momentum in IS and CLSCs studies, is only briefly considered in CE literature by Genovese et al., (2017). They argue that the CE concept presents a framework for the creation of shared value through the collaborative engagement of businesses within and beyond their supply chains. Thus, a clear gap in extant literature is identified, warranting investigation into the importance of collaborative supply chain relationships in the successful application of the CE framework.

2.7 Summary

Overall, the literature discussed has presented shortcomings in achieving sustainable supply chains. While IE, IS and CLSCs present different factors each framework considers crucial to moving towards more sustainable practices, they have failed to take a holistic approach. CE presents a comprehensive framework for addressing sustainable economic development, however, fails to investigate how supply chain relationships can assist this transition. Chapter 3 incorporates the factors identified in previous literature, using these as the basis for achieving collaborative supply chain relationships in the CE framework.

Chapter 3: Conceptual contribution and theoretical underpinnings

3.1 Introduction

The theoretical underpinnings are hereby presented, followed by the study’s conceptual contribution.

3.2 Theoretical underpinnings

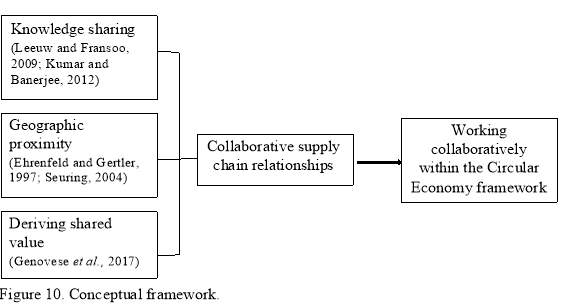

The role of collaborative relationships in CE is the main research gap this paper will address. As previously highlighted, IE extensively examined the impact of geographic proximity on the ability to form industrial ecosystems (Ehrenfeld and Gertler, 1997; Seuring, 2004); however, it neglected the importance of collaborative relationships in establishing industrial ecosystems. Subsequently, IS extended IE by incorporating the collaborative dimension to industrial symbiosis networks (Boons et al., 2011; Leigh and Li, 2015); however, it did not address the factors necessary for the establishment of collaborative supply chain relationships. Consequently, CLSCs addressed the importance of knowledge-sharing (Leeuw and Fransoo, 2009; Kumar and Banerjee, 2012) as a factor for establishing collaborative relationships; nonetheless, it focused on improving economic performance, failing to address the sustainability aspect of collaborative supply chain relationships. Finally, CE complements previous models by providing a framework for sustainable economic development and briefly considering the necessity to derive shared value from collaborative engagements (Genovese et al., 2017). However, collaboration, which previously received empirical attention, fails to be given adequate consideration in CE literature. Hence, the conceptual framework incorporates elements of the progressive development of sustainability models to address the aforementioned gap.

3.3 Conceptual framework

The framework extracts the three key constructs of collaborative relationships identified throughout literature and applies these as the basis for working collaboratively within the CE framework.

Chapter 4: Research methodology

4.1 Introduction

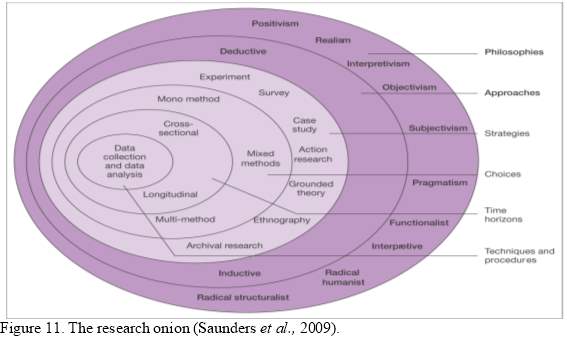

This section illustrates the adopted research strategy, data collection process, ethical considerations, alternative methods, and limitations. Saunders et al.’s (2009) model (Figure 11) is used as a guide for this project’s research methodology.

This section illustrates the adopted research strategy, data collection process, ethical considerations, alternative methods, and limitations. Saunders et al.’s (2009) model (Figure 11) is used as a guide for this project’s research methodology.

4.2 Research philosophy

The research philosophy adopted takes an interpretivist, axiological approach. Interpretivism describes research where the researcher takes an “empathetic stance” (Saunders et al., 2009, pp.116) and seeks to understand the subject’s point of view, taking a non-positivist approach. The axiological incline accepts that values are a guiding tool to human action (Heron, 1996), therefore the researcher’s values were used to make judgements about the way in which the research was conducted. This approach is most commonly used when undertaking qualitative data, using small samples to conduct in-depth investigation (Saunders et al., 2009). Contrastingly, a positivist approach assumes a theory-neutral stance to observation and adopts the ontological assumption that the researcher is separate from reality (Weber, 2004). Furthermore, it neglects the importance of acknowledging the effects of one’s own biases and assumptions in one’s research, although both philosophies seek to enhance one’s understanding of the world, despite contrasting approaches to reporting research (Weber, 2004).

Hence, a positivist approach is valuable in the collection of quantitative data, allowing it to be statistically interpreted, thus eliminating the need for bias consideration. This statistical data gathering allows the researcher to identify the relationship between variables (Saunders et al., 2009). Nonetheless, the aim of the research is to understand, rather than predict, human behaviour, thus the appropriateness of the chosen philosophy. Consequently, the data gathering process generated rich data about actual behaviours regarding supply chain collaboration and the motivations behind this.

4.3 Research approach

The research adopted an inductive approach. Saunders et al., (2009) describe this as a method used to collect data, and then identify common themes within it. It permits a more flexible structure, enabling the researcher to shift research emphasis as it progresses. Subsequently, an in-depth analysis was conducted.

Contrastingly, a deductive approach is predominant in quantitative methods, where hypotheses are presented and tested, and where law is the foundation for the explanation, anticipation and prediction of phenomena, thus allowing it to be controlled (Collis and Hussey, 2003). Although this method provides quantifiable, replicable results, it seeks to generalise social behaviour and interpretation, therefore ignoring individual experiences (Saunders et al., 2009). Due to the qualitative nature of the research project, and the interpretivist philosophy adopted, an inductive research approach was considered most appropriate.

4.4 Data collection

Considering the limited availability of literature which focuses on supply chain collaboration within the CE framework to analyse food waste, primary data will be used to investigate the research aim. As explored in the literature review, the majority of studies have focused on theory-building (Dey et al., 2011; Jurgilevich et al., 2016) and framework development (Boons et al., 2011; Kumar and Banerjee 2012). Hence, a need to investigate supply chain collaborative relationships within the CE framework in a specific industry, was identified. The research adopted a similar data collection method to Pagell and Wu’s (2009) study by using semi-structured interviews; it built upon it by focusing the sample to one industry, as per Hassini et al.’s(2012) recommendation, thus allowing in-depth investigation into similar supply chains, supporting the research objectives.

4.4.1 Semi-structured interviews

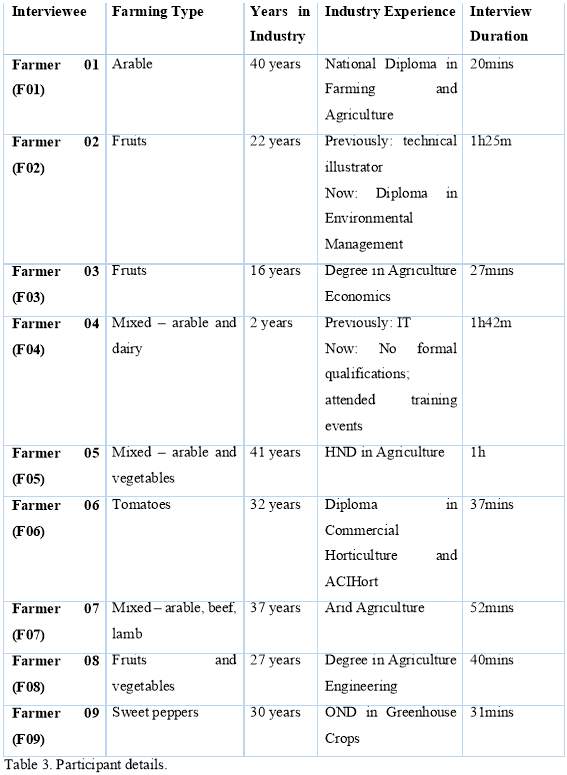

The research adopted a mono-method of data collection; nine semi-structured interviews were conducted with different farmers (Table 3) to explore the research topic. Participants were identified through LEAF; the farming sector was not part of the inclusion criteria to allow flexibility in investigating experiences and behaviours.

In semi-structured interviews the researcher has an interview guide of questions and topics that need to be covered. This method allowed interviewees freedom of response and ensured that key research areas were covered, allowing room for exploring other points of relevance which emerged from the discussion, without steering too far from the research aim (Bryman and Bell, 2015). However, it is recognised that semi-structured interviews have considerable limitations, including subjectivity in the interviewer’s interpretation (Bryman and Bell, 2015), lower reliability and validity as compared to structured interviews, and difficulties in research replication (Saunders et al, 2009). Nevertheless, this method was considered most appropriate due to the interpretivist approach adopted; it is also of relevance given previous study’s use of this method (Pagell and Wu, 2009): the current study adopted a similar research methodology with a different focus to further contribute to the literature.

4.4.2 Procedure

Participants were gathered through homogenous purposive sampling, focusing on a particular group where members are similar. This allowed data collection to be information-rich (Patton, 2002) rather than statistically representative, thus enabling the group to be studied in depth (Saunders et al., 2009).

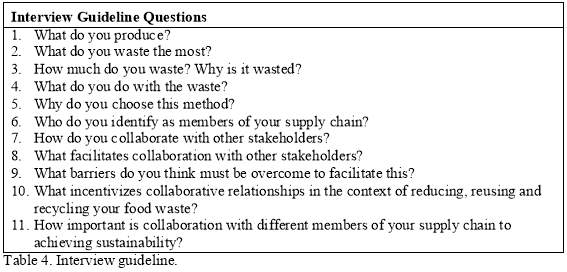

Twenty-eight individuals were targeted from farms across Southern England, of which fourteen responded, and nine agreed. The participants were firstly contacted via telephone, subsequently being emailed further information about the research. Six face-to-face interviews and three telephone interviews were scheduled. Eleven guideline questions (Table 4) formed the basis for the interviews, although participants were able to add comments emerging from the discussion.

Twenty-eight individuals were targeted from farms across Southern England, of which fourteen responded, and nine agreed. The participants were firstly contacted via telephone, subsequently being emailed further information about the research. Six face-to-face interviews and three telephone interviews were scheduled. Eleven guideline questions (Table 4) formed the basis for the interviews, although participants were able to add comments emerging from the discussion.

This structure ensured unexpected topics were explored (Sampson, 1972), contributing to the information-rich nature of the sampling approach. Interviews lasted up to an hour and forty-two minutes, depending on participants’ level of cooperation. Answers were recorded and a verbatim transcript produced.

4.5 Data analysis

Given the interpretivist approach to data gathering, a thematic analysis was conducted (Strauss and Corbin, 2008). Additionally, a computer aided qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS), NVivo, was used to identify the most frequently used keywords related to the identified themes. This approach was considered most appropriate as it maintains the value of qualitative methods whilst achieving the structure and direction observed in quantitative data (Boyatzis, 1998).

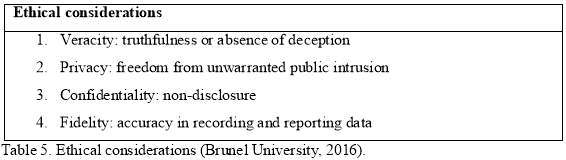

4.6 Ethical considerations

The current study took into account basic research ethics considerations of informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality. It also considered the University’s four key areas of ethical data gathering (Table 5).

The current study took into account basic research ethics considerations of informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality. It also considered the University’s four key areas of ethical data gathering (Table 5).

These issues were overcome by recording the interviews and informing participants of the purpose of the study, guaranteeing their right to withdraw from it at any moment (Appendix 1). Confidentiality was maintained by anonymising participants and any stakeholders they may have identified by name, ensuring interviews are not traceable.

4.7 Alternative methods

4.7.1 Primary vs Secondary data

Secondary data gathered by organisations is recognised by Stewart and Kamins (1993) as being of a higher quality than that gathered by an individual. Its ease of replicability increases its validity as results can be compared to previously recorded data (Rabinovich and Cheon, 2011). Nonetheless, secondary data is collected for a specific purpose which differs from one’s own research objective (Denscombe, 2007), and as such, may be only partly applicable. Consequently, given the specificity of the current study’s aim and the identified gap the research aims to fill, primary data collection was deemed most appropriate.

4.7.2 Quantitative vs Qualitative

Although quantitative data is useful in establishing relationships between variables, it does not allow data to be interpreted for its complexity and ambiguity given a specific context (Milliken, 2001; Cassell et al., 2006). Furthermore, qualitative data is concerned with the interviewee’s point of view, rather than focusing on the researcher’s interest, as is observed in quantitative data. Discussion of seemingly off-topic subjects are encouraged, as they highlight what the interviewee believes to be relevant, allowing related sub-topics to be explored – this is greatly discouraged in quantitative data gathering (Saunders et al., 2009). Consequently, qualitative data was deemed most appropriate for addressing the research aim.

4.7.3 Data Collection

Alternative qualitative data collection methods included unstructured and structured interviews. Unstructured interviews are conversational (Burgess, 1984); the interviewer uses an aide-mémoire as prompts to ensure a variety of topics are discussed (Bryman and Bell, 2015). This method is more widely used in exploratory scenarios where interviewees are allowed to discuss the topic freely (Saunders et al., 2009). Although this enables a vast amount of data to be gathered, it may lead to the discussion of loosely-related topics and is more time consuming than alternative data collection methods (Saunders et al., 2009; Bryman and Bell, 2015). Due to the time constraints present with the research, a semi-structured approach was considered most effective in collecting data.

Contrastingly, structured interviews follow a set protocol; they are used to collect quantifiable data and do not allow exploration of related sub-topics, limiting participants’ ability to express their thoughts (Saunders et al., 2009). Given the research’s aim to understand farmers’ interactions with supply chain members, a deeper understanding of such relationships was necessary to achieving such aim.

4.8 Limitations

Practical considerations taken into account included time constraints and participant sample size. Participants were contacted as early as possible and interviews were scheduled during a three-week period, following ethical approval. Given the specificity of the selected sample, the ideal number of interviews was considered to be between seven and ten.

Furthermore, interviewer bias is a limitation to response interpretation (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008) as the data gathered is open to the researcher’s interpretation (Kvale and Flick, 2007). To address this, interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, allowing an accurate and unbiased reporting. Nonetheless, it must be considered that the researcher’s interpretation inevitably influenced the analysis of the data.

Finally, the theoretical limitations considered included a lack of reliability, validity and generalisability. Due to the limited sample size, the data can lack reliability if universally applied. However, findings derived from this method are not intended to be repeatable (Saunders et al., 2009), given the complexity of supply chain relationships. Furthermore, despite a degree of subjectivity present in qualitative research, the study is of high validity given that it meets the research aim. Moreover, this research method is intended to reflect reality at the time of data collection (Marshall and Rossman, 1999); hence, it is unsuitable for replication and generalisability. Nonetheless, given the theoretical compatibility of the findings to existing literature, the research demonstrated it is of broad theoretical significance (Marshall and Rossman, 1999), thus counteracting generalisability limitations.

Chapter 5: Findings, analysis and discussion

5.1 Introduction

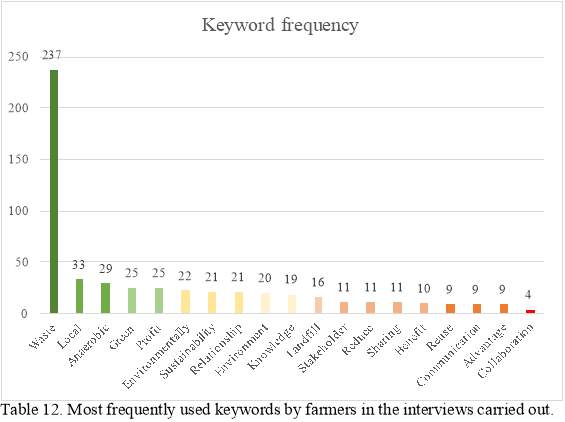

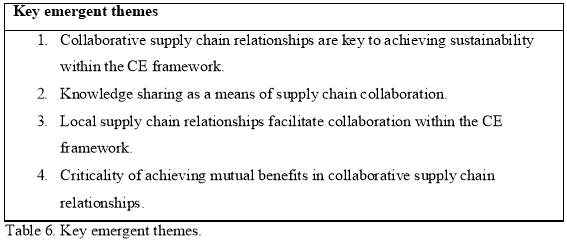

This chapter focuses on the main themes derived from the interviews; the analysis and discussion focus on how the information gathered corroborates or deviates from extant literature. The main themes identified are summarized below (Table 6). A frequency graph is presented (Figure 12) to illustrate the most commonly used keywords (Appendix 4).

This chapter focuses on the main themes derived from the interviews; the analysis and discussion focus on how the information gathered corroborates or deviates from extant literature. The main themes identified are summarized below (Table 6). A frequency graph is presented (Figure 12) to illustrate the most commonly used keywords (Appendix 4).

5.2 Theme 1: Collaborative supply chain relationships are key to achieving sustainability within the CE framework

A key finding which surfaced from the interviews was that of collaborative relationships enabling the achievement of sustainable practices. In accordance with extant literature (Chertow, 2007; Porsch, 2010; Boons et al., 2011; Lombardi and Laybourn 2012; Leigh and Li, 2015; Sarkis et al., 2011; Bell et al., 2013; Matopoulos et al., 2015), collaborative relationships are essential to transitioning towards more sustainable supply chains, as observed in IS, CLSCs and CE studies. Participants were emphatic about the role collaboration plays in their sustainable waste management activities. To further investigate this, the researcher asked “How important is collaboration with different members of your supply chain to achieving sustainability?”; F02 replied:

“you can’t survive on your own and you couldn’t even not try to work with other people”

F06 extended this view by saying:

“Vital. Vital. It’s the only way you do it; you cannot do that on your own […]. We need to share that best practice between producers, but also need all the stakeholders in the whole supply chain to interact to be able to get a message across to the consumer”

These excerpts corroborate with literature emphasising the need for collaboration in symbiotic relationships (Lombardi and Laybourn 2012; Leigh and Li, 2015) and closed-loop supply chains (Sarkis et al., 2011; Bell et al., 2013; Matopoulos et al., 2015), and thus could be easily applied to relationships within the CE framework. Additionally, this supports the movement observed throughout literature from IE concepts emphasising geographic boundaries (Ehrenfeld and Gertler, 1997; Seuring, 2004) and reuse and recycle of materials (Geyer and Jackson, 2004; Jacobsen, 2006) as primary determinants of sustainability, to frameworks supporting higher levels of sustainable practices through the incorporation of collaboration. Hence, higher levels of sustainable practices require greater involvement with supply chain members, as each theory of sustainability, IE, IS, CLSCs and CE, respectively, incorporates a further element to closing the loop of material flows.

5.3 Theme 2: Knowledge-sharing as a means of supply chain collaboration

A collaborative culture became a prominent theme throughout the interviews. When asked how collaboration takes place in their supply chains, interviewees consistently pointed to ‘knowledge-sharing’ as the basis of most collaborative relationships. This is consistent with Leeuw and Fransoo, (2009) and Kumar and Banerjee’s (2012) research, which suggest that collaborative relationships may suffer in the absence of a culture of knowledge and skill sharing. To explore the role that a collaborative culture plays in supporting supply chain members to work within the CE framework, the researcher asked “How do you collaborate with other stakeholders?”; F06 replied:

“We went out to the University of Berkley California, linked to the green science department of your university, […] and we’ve found that we can […] make the basis for a carton punnet to put our tomatoes in. […] we’re working with a commercial company and another university, […] we’ve made cellophane out of the cellulose in tomato leaves.”

This clearly demonstrates the role that knowledge-sharing plays in supporting collaborative relationships in exploiting opportunities to recycle waste, a key component of the CE framework (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Winans et al., 2017).

F05 commented on the role of knowledge-sharing as a means to increase the percentage of produce meeting specifications, which in turn reduces waste, demonstrating an understanding of the importance to achieve the first ‘R’ of the CE hierarchy (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Jurgilevich et al., 2016). He said:

“We collaborate closely with all our packing customers who help and advise on how to get the perfect spec for different products and we have our own agronomist specialist in each sector […] and they help us to try and get as much of our crop into spec as possible”.

F03 extended the notion of waste reduction by sharing knowledge of produce through their Open Farm Sundays:

“We do Open Farm Sunday, we meet different customers, we take them around the farm and talk about fruit with different people – that’s our exposure to the customer […] and you hope with years to come every farmer is participating in that, that something will change”.

This was also observed in F06’s interview, where he stated his role as knowledge-sharer:

“[…] I’m communicating into the Government that way, […] I do lots of things like Open Days for LEAF. […] as busy as I am, […] I still do gardening, doing speeches and things to try and promote what we do, […] particularly around sustainability of the way we produce”.

These are consistent with Kumar and Banerjee’s (2012) framework as well as the established hierarchy within the CE framework (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Jurgilevich et al., 2016). Interviewees acknowledged the role knowledge-sharing plays in the ability to work collaboratively within the principles of reducing, reusing and recycling waste, doing their part in varying degrees. However, F07 commented on the detrimental effect he believes knowledge-sharing can have:

“People say it’s a great thing but you know […]. We’re getting much more out of the resources and that’s what I want… well, as a producer that’s what I want, I wouldn’t want the whole industry to do that otherwise […] the price would just plummet’.

His view on knowledge-sharing contradicts the importance Kumar and Banerjee (2012) placed on this element of their framework. However, it follows the traditional view that sharing unique knowledge may hinder the business’ competitive advantage, posing “a dilemma for firms seeking to explore collaborative links” (Miemczyk et al., 2016, pp. 454). This is consistent with Esty and Porter (1998), who considered sharing core knowledge to hinder market advantages. This was thought to have been disproved by Singh and Power (2014), who argued that knowledge-sharing in supply chains acts as a contributor to improve different aspects of performance. However, this view is only shared by one interviewee, with all others considering knowledge-sharing as key to working with the CE framework. This may call for further research to determine whether fear of losing competitive advantage deters knowledge-sharing in supply chain collaboration towards CE. Nonetheless, this reinforces the need for all stakeholders to derive shared value from the collaboration, which CE advocates and emphasises as crucial for sustainable economic development to be achieved (Genovese et al., 2017).

5.4 Theme 3: Local supply chain relationships facilitate collaboration within the CE framework

Another emergent theme was that of keeping supply chain relationships local, defined in IE and IS literature as geographically bound industrial systems (Ehrenfeld and Gertler, 1997; Seuring, 2004; Yuan and Shi, 2009; Yu et al., 2013). Interviewees frequently mentioned that their waste disposal methods were influenced by the proximity of collaborating stakeholders. To investigate drivers of supply chain collaboration, the researcher asked “What facilitates collaboration with other stakeholders?”; F02 replied:

“Our main waste contractors are about 10 miles away so we do like to keep it all nice and local. It’s easier to build a relationship”

This was expanded by F03, who explained how their choice of waste management stream is based on a local supply chain member:

“we already have the business from the factory that supplies that anaerobic digestion power […] and we just go on the piggy back of that really, it’s easier for us as a farm […].”

In support, F09 explained the benefits derived from locally disposing of fruits which are unfit for human consumption:

“fruit that we’ve got like that or any that we’ve got in the pack-house that they grade out, that will go to a local farmer who will feed it through his cattle […]. It’s the convenience of it […] the farmer makes a lot of sense for the fruit part of the equation”

Given farmers’ emphasis on locally developed relationships, a clear deviation from recent research (Lombardi and Laybourn, 2012; Leigh and Li, 2015) is observed. Although Lombardi and Laybourn (2012) and Leigh and Li (2015) do not dismiss the importance of geographic proximity, they place it as a secondary contributor to achieving sustainable development, which is contrary to the study’s findings that geographic proximity of supply chain members involved in collaborative relationships is still critical to achieving supply chain sustainability. This is due to geographic proximity allowing supply chain members to “build a relationship” (F02) and due to “the convenience of it” (F09), in line with previous studies (Ehrenfeld and Gertler, 1997; Seuring, 2004) which place equal importance on geographic proximity and relationship building. However, whereas previous studies (Ehrenfeld and Gertler, 1997; Seuring, 2004) investigated geographic proximity and collaborative relationships as separate factors contributing to frameworks of sustainable development, the research findings show that these factors are in fact, interlinked, i.e.: the formation of collaborative relationships is facilitated by geographic proximity, showing a cause-effect relationship between the factors.

Nevertheless, these findings may be unique to the industry, and more specifically, to the supply chain members under investigation. Interviewees revealed that “you don’t want big lorries thundering down the countryside, moving what is effectively fuel” (F04) and “the actual green waste, all we do with that is we will chop that up and we will spread that on farmland adjacent to the Nursery” (F09). The comments reiterate that collaborative relationships formed locally are for “the convenience of” (F09) physical movements of waste, or potential waste, which are introduced as value into another stakeholder’s system. This demonstrates that the nature of the exchange determined the importance of having local collaborative relationships, as F06, due to the nature of the produce, preferred to deal with waste and potential waste “in house” (F06), instead forming long distance collaborative relationships with “the University of Berkley” (F06), which revolved around exchange of knowledge and information, thus not requiring physical proximity. Consequently, this prompts the need for research investigating the role of geographic proximity in different stages of a supply chain, as well as in different industries, to assess whether the importance of geographic proximity is dependent upon industry or exchange type. Additionally, the cause-effect relationship hereby observed should also be investigated further in different contexts, to assess whether the same interrelation is found in different industries.

5.5 Theme 4: Criticality of achieving mutual benefits in collaborative supply chain relationships

The final emergent theme was the importance of achieving mutual benefits from the collaboration in the management of food waste. Genovese et al., (2017) termed this ‘shared value’ and argued that the CE concept provides a framework which enables the creation of such value. To further investigate this, the researcher asked “What incentivizes collaborative relationships in the context of reducing, reusing and recycling your food waste?”; F09 replied:

“because […] there’s a mutual benefit for everybody, it has that strength to hold the relationship together. If there was a disadvantage to somebody […] then it would probably struggle a bit.”

Although not acknowledged in sustainability literature, F09 presents the view that their supply chain relationships are supported by goal congruence (Angeles and Nath, 2001; Cao et al., 2010), “because there’s a benefit” (F09), which demonstrates that it is secondary to the possibility of achieving advantages from the collaboration. Similarly, interviewees frequently described the intensity of collaboration as being relative to the activity from which they could derive the highest shared value. F04 described how “somebody had the bright idea” of using linseed straws to build “temporary wall of bale alongside the silage camp” as it could not be used as an immediate fertiliser. Similarly, F06 pointed to the creation of a separate business as a method of dealing with “fruit which is literally just knocked on the floor and there’s nothing wrong with it” and described this solution as “one of our most profitable parts of the business”. These efforts demonstrate that most collaborative relationships centred around waste prevention are those from which the highest value can be derived, consistent with the CE hierarchy (Sakai et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013; Jurgilevich et al., 2016) and its ability to create shared value (Genovese et al., 2017).

However, F02 presented a different viewpoint:

“[…] the end result really does interest me because I’m always fascinated with these new things […] trying to find how to sort it [waste] but it’s got to work for us as well, and I think that’s why it’s not really taken off”

F02’s statement shows further discordance with Angeles and Nath (2001) and Cao et al.’s (2010) studies; he explains that, although the congruence of their goals created the opportunity to form a collaborative relationship, it did not present enough mutual benefits, hence the collaboration had not “really taken off” (F02). Nonetheless, F03 explained that they maintain relationships with their retailers despite the misalignment in goals. F03 described their efforts to reduce waste by attempting to loosen supermarket specifications; however, the latter “have to make money” (F03) and do not pursue waste reduction although they have “the power to change that [customers’] perception” (F03). Hence, contrary to F09 and F02’s observations, there is a possibility of forming collaborative relationships, albeit not a satisfactory one, despite a divergence in goals. Consequently, supply chain power disparity strongly influences which and how supply chain goals will be pursued.

These excerpts shift the emphasis observed in literature of goal congruence as the relevant factor in collaborative relationships and place greater significance on the possibility and extent to which mutual benefits can be derived. This is especially significant in sustainability settings and reiterates Genovese et al.,’s(2017) argument for the creation of shared value as a result of partaking in collaborative supply chain relationships in a sustainability setting, particularly the CE framework. Hence, scholars should place greater emphasis on the creation of shared value and consider investigating this as a catalyst for collaboration in supply chains in the context of CE.

5.6 Summary

This chapter used data collected through semi-structured interviews and analysed this in relation to findings from previous research. Despite most findings aligning with extant literature, key divergences were observed: firstly, shared value creation, which previously had not received enough attention, emerged as a critical factor in establishing collaborative relationships in the CE context. Secondly, goal congruence was highlighted with varying degrees of importance among interviewees, suggesting further research into this construct as an important factor in sustainability settings is warranted. Lastly, geographic proximity was highlighted as a catalyst to collaborative supply chain relationships, thus disagreeing with current research which identifies it as separate from collaborative relationships. Overall, the identified themes are relevant in the synthesis of previous research.

Chapter 6: Conclusion

6.1 Main findings

The most prominent themes identified were: collaboration as a foundation for working within the CE framework; knowledge seeking and geographic proximity as catalysts for collaboration; and the need to derive shared value for the formation of successful collaborative relationships. These are in line with the proposed conceptual framework; specifically, they reiterate that factors identified in IE, IS and CLSCs studies are applicable to CE literature. In particular, the research findings corroborate with existing literature, reinforcing the reoccurring argument that collaborative relationships are essential to transitioning towards more sustainable supply chains (Chertow, 2007; Posch, 2010; Boons et al., 2011; Lombardi and Laybourn 2012; Leigh and Li, 2015; Sarkis et al., 2011; Bell et al., 2013; Matopoulos et al., 2015). Additionally, the findings echo Genovese et al.’s(2017) argument that CE provides a platform where shared value enables collaborative relationships.

Conversely, the interviews revealed that, contrary to Seuring’s (2004) study, geographic proximity is not a prerequisite for the formation of collaborative relationships where the nature of the collaboration entails the exchange of information and knowledge. Nonetheless, the findings suggested that this is still relevant where exchange of materials takes place. Finally, the findings uncovered the construct of goal congruence, not previously identified in sustainability literature. However, in contrast to Angeles and Nath (2001) and Cao et al.’s (2010) studies, goal congruence is secondary to the possibility of achieving shared value, demonstrating that the latter is most relevant.

6.2 Limitations

The most significant limitation to the study was the limited accessibility to the selected sample, i.e.: farmers. A larger sample size would have ensured the data was more representative and reliable, giving a better representation of how farmers in the UK are working collaboratively to manage food waste. Additionally, a mixed method approach to data collection, through the use of surveys, would have overcome the replicability concerns present with qualitative data; moreover, it would have addressed the sample size limitation by giving access to farmers whose contact details were kept private by the organisations to which they are affiliated.

6.3 Recommendations

The main findings suggest that interviewees are interested in forming collaborative relationships which help them manage their food waste more efficiently. As such, the creation of formal networks where different supply chain representatives can gather to share knowledge and best practice may be useful for farmers. This is especially valuable for the early stages of the supply chain, which can be neglected by upstream supply chain members who hold considerable power. Additionally, farmers can benefit from greater support from retailers in the prevention of food waste. Retailers can do this by creating a platform for communication between farmers, who have the knowledge of produce, and buyers, who hold the decision-making power in purchasing their produce.

6.4 Contributions

Theoretically, the study contributes new knowledge to the sustainability field, bringing together factors of collaboration previously investigated separately, i.e.: knowledge sharing, geographic proximity, and shared value, and applying them to the relatively new model of sustainable economic development, the Circular Economy. Additionally, it investigates these in relation to food supply chains, where the pillars of CE can be easily applied given the nature of the industry.

In practice, the study is of use to supply chain managers wishing to transition towards CE practices by highlighting the key elements needed in establishing collaborative relationships within their supply chains. Furthermore, it incentivizes farmers who have shown reluctance to share knowledge, to do so through informal and formal networks, supporting industry-wide collaboration.

6.5 Future research

The discrepancies observed between the identified themes and existing literature revealed avenues for further research. Specifically, future research should investigate if fear of losing competitive advantage deters knowledge-sharing in supply chain collaboration towards CE. Furthermore, as the importance given to geographic proximity by interviewees differs from that in extant literature, scholars should consider examining this variable further. Particularly, it should be studied in relation to different industries and different types of exchange, i.e.: knowledge or physical. Finally, the significance of shared value identified in the interviews warrants further research into its role as a catalyst for collaboration in supply chains in the context of CE, as current studies of this are limited.

6.6 Conclusion

The investigation met its aim to understand how supply chain stakeholder relationships can contribute to food waste management within the CE framework, particularly how farmers engage with different stakeholders to achieve this. It recognizes its limitations, contributes new knowledge to existing CE literature, and provides practical recommendations for further studies.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Sustainability"

Sustainability generally relates to humanity living in a way that is not damaging to the environment, ensuring harmony between civilisation and the Earth's biosphere.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: