Reflective and Reflexive Activities in Short Term Study Abroad Programs for Student Development

Info: 15826 words (63 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Background

Traditionally educational opportunities in the United States were largely limited to wealthy males, serving a small minority who could afford the privately controlled and exclusive academies (Ogden, 2007). Wealthy families who could afford education were also able to finance traveling abroad for either education or leisure (Brooking, 2010). The common school movement in Massachusetts however, ushered in a commitment to educate everyone, views consistent with the views of founding fathers Washington, Jefferson and others, who saw an educated society as the foundation upon which a democracy could be based (Ogden, 2007). The founding father’s views of an educated society meant American academies encouraged the study of subjects considered to be practical or utilitarian (Ogden, 2007).

In the 1900s, thanks to waves of immigrants of mainly European descent, accompanied by increasing child welfare concerns and a series of compulsory attendance laws, the population explosion resulted in demands upon public schools that had been the privilege of the best, brightest, and most motivated of students (Ogden, 2007). During the 1920s and 30s teachers in public schools were preoccupied with finding the ultimate methodology learning that would unlock all student minds and open the floodgates of cognition (Ogden, 2007). For American education in the 20th century, most of the proposed changes were attempts to give learners better roles in the classroom, a view that sought to disconnect the concept that teachers were dominant and learners were passive and learning required only classroom cognitive skills (Buhler, 1988). Criticism of education mounted steadily as critics deplored the lack of standards, loss of rigor, and concentration of effort on subjects considered by many to be beyond the scope of the schools (Ogden, 2007).

Preexisting metaphors of the school presented a conveyor belt which took in raw, uneducated but willing students and produced the necessary workers and professionals for a well ordered and smoothly functioning society (Ogden, 2007). However, rapid and remarkable changes in the society within the context of increasing globalization processes forced the national education system to play a crucial role in enhancing a country’s development and the creation of a highly qualified workforce that were able to create, adapt, access and apply new knowledge and technologies (Bidyuk, 2016). Students were expected to link their education to economic realities, social processes, technological and media innovations, and cultural flows traversing national boundaries, requiring them to develop new skills far ahead of what most educational systems could deliver (Eisenhart, 2008).

The higher education system in the United States recognized the need to equip students with the skills needed to navigate the complexities of an increasingly globalized world (Van Deusen, 2007) through a vision to improve global business, cross cultural awareness, and global engagement (Zahabioun, Yousefy, Yarmohammadian, & Keshtiaray, 2013). Globalization became the most fundamental challenge higher education institutions faced, according to the outstanding theorist of higher education and vice chancellor of the Kensington University P. Scott (Bidyuk, 2016). In U.S. higher education institutions, the study abroad movement grew, fueled by the urge to enhance intercultural knowledge, intercultural communication skills, and to gain competencies necessary to function in the global marketplace (Tucker, Gullekson, & McCambridge, 2011).

Following the end of the First World War, university sponsored study abroad truly began (Brooking, 2010). Two pieces of legislation passed by the U.S. Congress between 1944 and 1946 gave study abroad programs national backing and enabled students from across the nation to participate (Brooking, 2010). Higher education institutions encouraged a global view of the exchange of ideas, scholars, and students, not just through exchanging people and scholars, but also through developing internationally recognized curricula and promoting the partnerships with different higher education institutions all over the world (Bidyuk, 2016). Campus statements began including phrases such as “cultivating diversity”; “developing communities that recognize and respect difference”; and “increasing international and global understanding” (Anderson, Lorenz, & White, 2016). Phrases such as global citizenship, geopolitics, sustainability, multilateralism, global competency, and empathy, became part of the lexicon of higher education (Babb, Womble, & De’Armond, 2013)

Nearly all higher education institutions established or begun the process of making commitments to expand their global exposures so students can participate in a global society, partially through establishing international study abroad programs (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013). Even though faculty members serve as catalysts and initiators of international programs and collaborations (Finkelstein, Walker, & Chen, 2013), higher education institutions face five challenges regarding increasing globalization: 1) institutional mission definition; 2) funding structures and arrangements; 3) student engagement methodologies; 4) institutional transparency and accountability practices; 5) ability to partner in a variety of ways (Bidyuk, 2016).

Short term study abroad programs are perceived as the most efficient way to internationalize (Institute of International Education, 2009). Over 50% of students opted to participate in short term programs, making short term programs the most popular form of study abroad experience (Institute of International Education, 2013). Short term programs allowed students to have a more viable and affordable study abroad experience for students (Gonsalvez, 2013) without detracting from earned credits at their home institutions (Institute of International Education, 2009).

Students chose short term study abroad benefits not just for convenience, but the contextual learning that surpassed traditional classroom educational experiences (Domke-Damonte, Martin, & Fine, 2014). The study abroad environment provides an enhanced opportunity for learning concepts and process to be applied and observed, allowing a more focused educational experience for students (Drake, Luchs, & Mawhinney, 2015). According to Brooking (2010), research has shown that students who engage in study abroad programs experience multiple benefits, including increases in academic learning, cultural competence, foreign language proficiency, personal development, self efficacy and career development. In matched samples of students who had studied abroad versus those who had not, researchers found higher functional knowledge, greater knowledge of global interdependence, greater knowledge of cultural relativism, greater knowledge of world geography, and greater cultural sensitivity (Domke-Damonte, Martin, & Fine, 2014).

Study abroad learning experiences offered a rich variety and depth of learning spaces for a more focused educational experience abroad (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). However, the experiences of study abroad programs are not educational in and of themselves (Lutterman-Aguilar & Gingerich, 2002), but rather the reflection process which turns the experience into experiential education (Joplin, 1995). A need exists for a pedagogical frame that allows rich experiences to be critically analyzed and reflected upon (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). Action and reflection occur with an understanding that learning is an ongoing process that allows for the reflection about said experiences and then constructing new understandings (Joplin, 1995).

Donnelly-Smith (2009) found that students get the most from programs that are highly structured, require ongoing reflection, and include in depth experiences working or studying with host country participants. Allowing adequate time for reflection, discussion, and debriefing deepened student’s understandings of their experiences while also encouraging their development (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). Students should be encouraged to reflect on and connect their experiences in and outside of the classroom, reflection which in turn leads the student to conceptualize new thoughts and ideas based on their experiences, which leads to further action (Brooking, 2010). The reflection activities allowed the students to reflect on and observe their experiences from many perspectives (Kolb, 1984). The use of reflection also elicited an increase in students’ understanding of course concepts, allowing broader and deeper learning to occur (Brooking, 2010). The type and frequency of reflection within the programs differed, furthermore, the manner in which components were implemented had an effect on student outcomes (Brooking, 2010). Study abroad programs which lacked reflection showed lower rates of learning compared to study abroad program that included a reflection component, with many outcomes being linked to the reflection components of the study abroad program (Brooking, 2010).

Statement of the Problem

Being abroad does not promote language or culture, in fact, study abroad experiences do not guarantee that students’ worldviews would broadened and/or challenged, nor can students who participate in study aboard programs be guaranteed to have an increased cultural competency (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013).

The fact that students study abroad does not guarantee they will be successful academically or professionally (Brandauer & Hovmand, 2013). Just because students go abroad does not mean they will come back with the skills and knowledge they need to be successful in a global workforce (Brandauer & Hovmand, 2013). Considering the brief amount of time that short term study abroad students are in the host country, their exposure to the local culture is limited compared to students participating in long term study abroad (Brooking, 2010). Students can virtually isolate themselves, living with other Americans and frequenting only places catering to American students (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). Even if students are able to function in their host countries, they may not be able to make meaningful progress in developing intercultural competence if they do not learn how cultures function differently (Peckenpaugh, 2014).

Limited exposure prohibits well developed perspectives and cultural sensitivity, in fact, in some cases could merely reinforce negative stereotypes (Babb, 2013). More than good experiences, supporting pedagogies and education practices are required for students to develop cultural sensitivity (Younes & Asay, 2003). If students’ thoughts about their experience are not guided or critically reflected upon, students might be unable to understand new contexts, creating instead imaginary meanings made up of projection and negative stereotypes (Anderson et al., 2016).

Study abroad instructors are uniquely positioned to intervene in student learning through relationships with students that extend beyond the walls of the classroom (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Unfortunately, programs designed and led by faculty members or others who may have little or no experience with standards of study abroad program design and management can become little more than ventures (Institute of International Education, 2009). Anderson (2016) found that the most effective instructors are those facilitated intercultural learning for their students by serving as intercultural mentors, and supporting and guiding students through the incidents of cultural discord and created safe places for students to debrief. Effective instructors helped learners reflect on their own experience, helping organize and connect reflections to the knowledge base of the subject being studied (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012), maximizing the student development through intercultural learning immersive experiences opportunities (Anderson et al., 2016).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to examine and describe how faculty members in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences at the University of Georgia use reflective and reflexive activities in short term study abroad programs to encourage student development. The study sought to evaluate the way faculty members prioritize student learning and development in the design and management of short term study abroad programs as well to understand the way faculty members used program activities to support student learning and development. This study aimed to collect data that faculty members who are exploring the possibility of developing a study abroad program can utilize to incorporate reflexive activities into their curriculum.

The study was guided by the following objectives:

- Determine the factors that influence the activities faculty members chose to incorporate into their study abroad program

- Determine which reflective and reflexive activities are perceived as beneficial to student development

- Determine the perceived role of faculty members in student learning and development

Significance of the Study

Despite the assumption that study abroad programs lead to unique and beneficial outcomes for students, a dearth of consistent research exists on the outcome programs on student growth (Tucker et al., 2011). A gap in the literature exists on the use of reflective and reflexive activities on student development while studying abroad in short term programs. Studying faculty members who regularly incorporate reflective and reflexive activities into their short term study abroad programs will help create a model for producing outcomes identical to that of long term programs. Study findings can be used to compare the different strategies that faculty members employ when utilizing reflective and reflexive activities to stimulate student development, as well as determine which reflective and reflexive activities were most beneficial to student development, and determine the perceived role of faculty members in student learning and development. Findings will contribute to the development of models that assist faculty who plan to incorporate reflexive and reflective activities in their study abroad programs to assist student development.

Definitions

- Culture: An established framework of expectations and values in which a person views the world encompassing many ideas including, but not limited to: space, time, language, social relations, food, clothes, body, everyday life, religion, and rituals (Conner, 2013).

- Cultural development: the promotion of knowledge, respect and appreciation of different cultures.

- Curriculum: A set of expectations and requirements for an overall program of study (Forum on Education Abroad., 2009).

- Experiential Learning: educational strategy which combines experience, perception, cognition and behavior (Kolb, 2005).

- Globalization: The interconnectedness of the world’s economy, cultures, and all other aspects of life (Van Deusen, 2007).

- Globalized curriculum: Curricula with an international orientation in content, aimed at preparing students for performing professionally and culturally in an international and multicultural context (Crowther et al., 2000).

- Journal: written tool for promoting and deepening reflection.

- Orientation: group meeting explaining focal areas and highlighting key points for students in preparation for the upcoming study abroad program.

- Reflection: the focused and somewhat specialized serious thought that makes individuals aware of their reality (Benschop, 2002).

- Reflexive: the critical introspection that can nourish reflections as introspection leads to heightened awareness, change, growth and improvement of self (Ryan, 2005).

- Short term, study abroad program: In this study short term study abroad program was defined as a study abroad program taken for course credit lasting between one and six weeks in length (Institute of International Education, 2009).

- Student Development: the ways that a student grows, progresses or increases [their] developmental capabilities (Rodgers, 1990)

Delimitations

This study was delimited to faculty members of the University of Georgia’s College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences who incorporate reflective or reflexive activities into their study abroad program curriculum.

Limitations

Findings from qualitative studies cannot be extended to wider populations with the same degree of certainty because the findings were not tested to discover whether they are statistically significant or due to chance (Atieno, 2009). Therefore, the results of the study are limited to the participants of this study and do not represent the experiences of all faculty members of the University of Georgia and may not be generalized to other U.S. institutions. The small sample size faculty members who stated they use reflective or reflexive activities in their curriculum was the primary limitation of this study. Additionally, the conceptual framework and the literature review is based on scholarship where most of the work has examined overall student development, rather than the intentional use of reflective and reflexive activities

Chapter Summary

U.S. higher education institutions made global awareness and engagement a priority (Babb, 2013), fueled by the urge to enhance intercultural knowledge and to gain competencies necessary to function in the global marketplace (Tucker et al., 2011). Studying abroad allowed students the opportunity to learn through a rich variety of learning spaces (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Furthermore, short term study abroad programs allowed students to have an accredited international education experience (Institute of International Education, 2009) via an affordable study abroad experience (Gonsalvez, 2013).

Research on study abroad has shown that students who engage in these programs experience multiple benefits; however, there is no guarantee that study abroad experiences in and of themselves will broaden and challenge students’ worldviews (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). Experiences are not educational in and of themselves (Lutterman-Aguilar & Gingerich, 2002), but rather the reflection process turns the experience into an experiential education (Joplin, 1995). For students to develop cultural sensitivity, students require a good experience and supporting pedagogies (Younes & Asay, 2003).

The purpose of this study was to explore the way faculty members prioritize student learning and development in the design and management of study abroad programs as well as pre program, on site, and post program activities that support student learning and development. The study aimed to determine the factors that influence the activities faculty members chose to incorporate into their study abroad program, determine which reflective and reflexive activities were most beneficial to student development, and determine the perceived role of faculty members in student learning and development to understand how faculty members can incorporate reflexive activities into their curriculum.

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Research Objectives and Introduction

Chapter one introduced education in the United States and the rise of globalization in education, with an emphasis on the role short term study abroad programs in the promotion of cultural development in students. Student benefits and challenges of study abroad programs were also discussed. Studies have shown that being abroad is not enough to promote culture learning, and the experiences do not ensure changes in students. Supporting pedagogies and education practices are needed to develop cultural development. The purpose of this study was to explore the way faculty members prioritize student learning and development in the design and management of study abroad programs.

The following objectives guided the study: 1) determine the factors that influence the activities faculty members chose to incorporate into their study abroad program, 2) determine which reflective and reflexive activities are perceived as beneficial to student development, and 3) determine the perceived role of faculty members in student learning and development.

Chapter two will introduce a review of research and literature related to the outcomes of study abroad programs and the role of experiential learning, key elements of short term study abroad programs, and describe the conceptual framework for the study. The first part of this literature review focused on the historical background, the different types of study abroad programs, outcomes of study abroad programs, and the internalization of curriculum. The second section of this chapter will examine the format of short term study abroad programs (focusing on pre departure, on site activities, and post program activities) and some of the barriers to benefits students may experience. Section three will focus on reflective and reflexive activities and the role of faculty members in the learning process.

Background

Historically, American institutions of higher education were not involved in educational programs outside of their campuses; instead, individuals sponsored any travel abroad, educational or otherwise, for people of college age (Brooking, 2010). During the Colonial and Antebellum periods, Southern planters would send their sons to Europe for the “Grand Tour”, an educational rite of passage trip undertaken the upper class (Dulles, 1966). According to Dulles (1966), the number of Americans studying in Europe greatly increased during the Post Civil War period. However, American colleges and universities were not known to sponsor educational programs overseas and had little interest in doing so (Brooking, 2010). According to Brooking (2010), university sponsored study abroad in the United States truly began following the end of the First World War.

Increased global tensions served to highlight and deepen the need for greater international understanding and appreciation for diversity (Posey, 2003). Concurrently, the American higher education system started to recognize the need to equip students with the skills necessary to navigate the complexities of an increasingly globalized and interconnected world (Van Deusen, 2007). Campus mission statements reflected globalization goals, with three of the twelve most common campus goals being: appreciating diversity, building communities that acknowledge and respect difference, and international and global understanding (Anderson et al., 2016). American institutions sought to accomplish these goals via a variety of study abroad programs offered through colleges and universities (Posey, 2003). Study abroad programs were constantly changing and growing to meet the needs of institutions and national higher education policies (Hoffa & DePaul, 2010). Today, almost all United States universities have established or are in the process of establishing international study abroad programs and making further commitments to expand their global exposures so students can participate in a global society (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013).

Types of Study Abroad Programs

Traditionally, study abroad programs consisted of a group of humanities students from a particular institution traveling to another university in Western Europe during their junior year of undergraduate study for either one semester or an entire academic year, receiving full academic credit for programs taken abroad and enrolled in courses and shared living space with local students (Scally, 2015). Most recently, the study abroad definition included programs that result in progress toward an academic degree at a student’s home institution but excludes the pursuit of a full academic degree at a foreign institution (Forum on Education Abroad., 2009).

Program duration can range from long term programs (an academic year or longer) mid length programs (a semester or less), or short term programs lasting eight weeks or less (Institute of International Education, 2009). Short term programs can range from programs lasting a week that are conducted during school breaks, programs lasting three or four weeks conducted during the winter or summer breaks to longer programs of up to eight weeks (Gonsalvez, 2013).

Short term programs typically target full time students and allow students to complete up to 6 hours of academic credit, with ample opportunity for individual travel and exploration (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013). Short term programs can involve homestays, travel to multiple sites, and service or research experiences (Gonsalvez, 2013). Accredited institutions require 37.5 hours of contact time to be maintained for a three credit hour course (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013). The duration of the program has been a critical factor because time affects academic standards and the multitude of programmatic issues for the program directors, faculty, and students (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013). The different program structures all provide students with experiential learning by immersion in another culture, providing opportunities for learning by doing virtually 24 hours a day (Scally, 2015).

Rise of Short Term Study Abroad Programs

Expand study abroad opportunities to all students, particularly underrepresented students, such as minority students, low income students, students with disabilities, and students in non traditional fields, should be made a priority (Institute of International Education, 2009). Many institutions perceive short term programs being the quickest and most efficient way to “internationalize” (Institute of International Education, 2009). Furthermore, when the length of the program increases, the likelihood that a working student can participate decreases (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013).

In particular, short term, faculty led study abroad programs allow students to have an international experience without detracting from their ability to earn credits at their home institutions during the academic year or affecting their graduation requirements (Institute of International Education, 2009). Moreover, compared to longer programs, short term programs are a more affordable way to send students abroad (Institute of International Education, 2009). Short term study abroad programs have become more viable and affordable for students, and faculty now have a better grasp of maintaining and meeting the learning outcomes (Gonsalvez, 2013). Currently, short term programs have been found to be the most popular form of study abroad experience with 59% of students opting for a trip with this structure (Institute of International Education, 2013).

Outcomes of Study Abroad

Braskamp (2009) cites the overall goals of higher education including the learning, intellectual, moral, social, physical, and spiritual development of students. Study abroad programs offer a rounded education, by allowing participating students to gain international exposure (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013). Benefits of study abroad programs may include (1) increased academic credit towards graduation requirements, (2) foreign language course credit, (3) practical experience through hands on learning, (4) résumé building activity, and (5) an experience of a lifetime (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013). Although the overall goals of study abroad vary according to each individual program, many programs aim to strengthen students’ understanding of international issues, cultural awareness, language skills, and developing global citizenship skills (Scally, 2015). Lukosius & Festervand (2013) further separated the developmental processes into three major domains: cognitive (epistemological, awareness, knowledge), intrapersonal (identity, attitudes, emotion), and interpersonal (behavioral, skills, social responsibility).

Cognitive Outcomes

The intellectual growth and learning outcomes of students engaged in study abroad programs have been established in several studies (Brooking, 2010). In matched samples of students who had studied abroad versus those who had not, researchers have attributed the following differences to participation in study abroad: higher functional knowledge, greater knowledge of global interdependence, greater knowledge of cultural relativism, greater knowledge of world geography, and greater cultural sensitivity (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014). Research showed that students in study abroad programs integrate the course knowledge better than students in the same course at the home institution (Marine, 2013).

Interpersonal Outcomes

Higher education leaders and faculty are concerned with the intellectual development and learning of students, as well as the moral and social development of students such as intercultural competency (Braskamp, Braskamp, & Merrill, 2009). Posey’s (2003) study of the differences in educational achievement between study abroad participants and non participants moves beyond the commonly cited outcomes of personal development, language acquisition, and intercultural competence to demonstrate the impact of study abroad on skill building and human capital.

Education abroad literature often highlights the positive impact of study abroad, such as increased student’s global perspective, enhanced ability to learn, developed cross cultural awareness and sensitivity (Anderson et al., 2016). In the ongoing process of globalization, intercultural communication among nations leads to a workforce who can function in an increasingly interdependent world (Zhang, 2011). Study abroad programs have also been cited as preparing students to become competent business leaders capable of working in highly international environments and dealing with a culturally diverse workforce (Lukosius & Festervand, 2013).

Intrapersonal Outcomes

A student’s personal growth links with intellectual growth outcomes in study abroad programs (Brooking, 2010). The personal development of study abroad participants has been widely documented (Brooking, 2010). Evidence also exists that education abroad influences student’s attitudes, intercultural skills, and learning within a discipline (Braskamp et al., 2009). In general, an education abroad experience seems to have a general positive psychological impact on students (Braskamp et al., 2009).

In an increasingly globalized world, students need be prepared to interact with people of different cultural backgrounds, perspectives, customs, and beliefs (Braskamp et al., 2009). Higher education institutions embraced the idea that learning about other cultures was a critical component of becoming an educated person, succeeding at work, and becoming an effective citizen (Long, 2013). Education abroad has been recognized as an important catalyst for students developing personal attributes as a defining experiences of college students that advances them in their journey within a context of living in a global community (Braskamp et al., 2009)

Outcomes of Short Term Study Abroad Programs

Study abroad programs could not continue if they did not adequately prepare students (Drake et al., 2015). Furthermore, students report learning more in a study abroad context than in a traditional classroom (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014). Short term study abroad programs enhanced target language proficiency, increased out of class interactions, resulted in a deeper sociocultural understanding, fostered pedagogical and professional development and promoted personal growth (Scally, 2015). Short term study abroad programs require a more organized and intense application of instructional methods to provide opportunities for the same learning style support compared to the semester long course (Drake et al., 2015). Students became more receptive to learning concepts and process because the environment provided an enhanced opportunity for educational experiences (Drake et al., 2015).

In a study done by Drake (2015) comparing student academic performance on a short term study abroad program compared to a traditional semester long course, the study found no significant difference between the students’ performance on the final exam overall or isolated by the instructor. The performance on a final exam of a required business core course was compared between students who studied abroad and students who took a semester long version of the course with the same professors to ensure that the study abroad students were able to achieve a comparable level of learning. While the semester long students did perform nominally better for each instructor, the differences were both less than .05, which represented one question on a 20 question exam. Students over the two year period were able to learn the core material in the two week study abroad program at relatively the same level of competency compared those students who took a semester long version of the same course (Drake et al., 2015).

Another study, which evaluated the degree of global engagement of more than six thousand alumni from twenty universities who participated in study abroad programs over a period of fifty years presented evidence that duration of stay of students who study abroad is not significant (Paige, Fry, Stallman, Josić, & Jon, 2009). The researchers found no significant difference in global engagement scores between students who had studied abroad for longer or shorter time periods (Paige et al., 2009). However, a study done by Brooking (2010) found that students who enrolled in short term study abroad scored significantly lower on the global mindedness scale compared to their long term counterparts. In fact, short term study abroad participants had the same level of global mindedness compared students who indicated that they intended to study abroad (Brooking, 2010).

Globalization of Curriculum

Historically, even the most academically rigorous “junior year abroad” programs were primarily extensions of the home curriculum in subjects of languages or the arts (Long, 2013). Dependence on the home curriculum’s definition of what is important to learn and how it should be learned ensured the fragmentation of the educational component of study abroad (Long, 2013). Substantial changes in curriculums aimed to prepare students for working and living in global contexts (Zahabioun et al., 2013). However, gaps existed between the rhetoric of institutional policies on internationalization and how faculty members leading programs abroad understood and translated these policies into in their study abroad programs (Green & Mertova, 2016). The need for a shared vision to improve global business, cross cultural awareness, and global engagement for students must be continuously emphasized to the university community and more significantly be supported at the highest levels to allow for an expansion of study abroad offerings (Zahabioun et al., 2013). Many universities declared that graduate attributes such as global citizenship could be achieved through the internationalization of the curriculum (Green & Mertova, 2016).

Curriculum goals help in guiding a global framework and directing educational planning (Zahabioun et al., 2013). Ideally, a study abroad program should fulfill curriculum requirements (Eckert, Luqmani, Newell, Quraeshi, & Wagner, 2013). A generic study abroad program may not fulfill any graduation requirements especially if students already took elective courses (Drake et al., 2015). Requirements related to faculty contact hours with students and outcomes assessment must be satisfied for the institution to award academic credit (Drake et al., 2015). As Long (2013) stated, students today can learn subjects in a variety places, however, those studies continue emphasizing the home curriculum. Study abroad programs incorporated classes from the university’s regular curriculum, which created a greater demand for short term programs (Drake et al., 2015).

Ideally, curricula would emphasize active involvement, a variety of learning activities, and an element of choice to stimulate personal investment in learning (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). To truly capture the benefits of a logically planned experience, requires effective and logical curriculum design would be used to reduce disconnect between recall, understanding, and practice (Drake et al., 2015). However, the effectiveness of delivery methods varies by the educational context in which it takes place; actual program delivery mechanism must be decided after consideration of the overall context (Van Deusen, 2007). Domke-Damonte (2014) noted the criticality of intervening at pre departure, on site, and post return to create maximum learning benefits for students on study abroad programs. Examples of curriculum activities encouraging student development include: pre departure orientations, embedded written reflections, increased interactions with faculty and classmates, and post trip reflection meetings (Stebleton, Soria, & Cherney, 2013).

Format of Short Term Study Abroad Programs

Planning a study abroad program should start with defining the program objectives and outcomes which in turn guide the program content, format, location, length of travel, activities, and assessment (Marine, 2013). Leaders of short term programs are involved in every aspect of program administration, from identifying the community partner to initiating organized reflection (Brooking, 2010). Faculty leaders on short term study abroad trips often find themselves responsible for planning everything in the itinerary including flights, accommodations, ground transportation, meals, cultural activities, and the academic program (Drake et al., 2015).

Pre Departure activities

A number of studies have examined what programmatic changes can be made to prepare students for studying abroad and to support them during their stay abroad (Peckenpaugh, 2014). Pre departure considerations include student related factors, program orientation and culture, health and safety issues, behavioral issues, and logistics (Eckert et al., 2013). In a pre departure setting, explaining focal areas and highlighting key points for students in preparation for the upcoming study abroad program are necessary (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014).

Pre departure orientation

Orientations should include an introduction to the cultural conditions, historical evolution, and social issues within each study abroad location (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014). The vast majority of students have never traveled abroad before and the more information they know about international travel and the country to be visited prior to departure, the better they adjusted and the more they gained from the experience (Eckert et al., 2013). For students, proper preparation and setting expectations should be clearly defined in pre departure orientations, such as respect for each other, respect for the facilities being used, and respect for the professional host (Eckert et al., 2013). Furthermore, appropriate pre departure preparation and reflection provide a baseline experience of theoretical and conceptual learning for students (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014).

On Site Activities

Initial Orientation

This meeting usually happened shortly after arrival and was held in a room or lobby in the hotel where the group stayed at a predetermined time and location to discuss the plans and activities for the program and explain any changes that were made since the last pre departure session (Eckert et al., 2013). At the first orientation meeting, importance should be placed on reviewing the itinerary of the trip and distribution of the program syllabus along with expectations on course readings, assignments, research papers, participation requirements, and deadlines (Eckert et al., 2013).

Daily Meetings/Updates

Daily gatherings to discuss the daily itinerary and an end of the day wrap up to talk about insights and to remind everyone of the next day’s schedule were recommended because students typically fail at following an itinerary (Eckert et al., 2013). Group dinners, for example, provided an excellent opportunity to provide students with important details on the next day’s activities and requirements (Eckert et al., 2013). Daily meetings were helpful in reinforcing lessons learned and making observations that the students might have missed (Zahabioun et al., 2013). Boyle et al. (1999) asserted that time together where students have the opportunity to explore new ways of learning when in a different cultural context must be made a priority. The use of group based oral reflection had the added effect of encouraging dialogue between the program participants (Brooking, 2010). Boyle et al. (1999) stated the importance of time together where students have the opportunity to explore new ways of learning when in a different cultural context.

In Country Interactions

Tours of museums, research laboratories, historic labs, factories, and churches provided useful content or cultural appreciation if students recognized the clear connection to the program objectives (Marine, 2013). Professors, staff, peers, homestay families, roommates, supervisors and coworkers, tour guides, local citizens, and even other tourists comprised a student’s network of developing relationships abroad (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Meaningful relationships abroad not only eased the adaptive challenge of living abroad, they also facilitated transformative learning and the development of cultural competence (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012).

Program Assignments

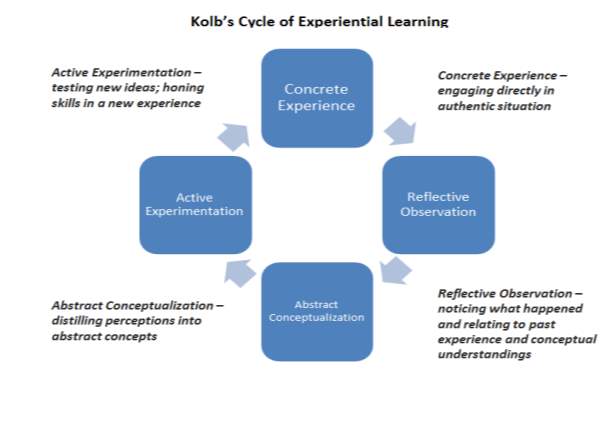

Action and reflection should be integrated with an emphasis on understanding learning as an ongoing process of having experiences, thinking about experiences, and then constructing new understandings and questions to take to another experience (Joplin, 1995) Therefore, development of the student assignments and preparation should be based on a strong appreciation of Kolb’s (1984) four learning abilities deemed critical to experiential learning: (1) concrete experience – to process the stimuli through cognitive memory; (2) reflective observation – to recover and consider their memories; (3) abstract conceptualization – to apply theoretical principles and concepts to the observed and experienced stimuli; and (4) active experimentation – to come to new understandings and problem solving. Eckert (2013) stressed the importance that to make assignments effective, expectations and firm criteria should be established.

Written Assignments

Writing is a method of discovery and reflective analysis (Craig, Zou, & Poimbeauf, 2015). Writing assignments can be blog entries, journals, or essays such as reflection papers. The proposed tasks encourage students to practically engage and reflect on their own development of intercultural awareness and the students’ experiences and reflections illustrate these processes in action (Holmes, Bavieri, & Ganassin, 2015). An advantage of blog use can be the documentation of the trip for the student, something for them to remember for some time afterward simultaneously allowing students to communicate with friends and family and providing another useful feedback source to potential students (Eckert et al., 2013).

Daily Journals

Journals have long been championed as tools for promoting and deepening reflection (Craig et al., 2015). Daily journals enabled students to tie course concepts to real world experiences and allowed the instructor to assess the depth of understanding each student attained (Drake et al., 2015). The journal trained students to observe their surroundings and resulted in a written record of these observations and travels, which helped students remember details of the localities, physical features, flora and fauna, statistics, and people encountered (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014). Journal writing assisted students in exploring the knowledge they have developed through their academic study abroad experiences (Craig et al., 2015).

Through journaling, retention of critical knowledge points and the connection of theory to practice allowed the incorporation of key transformational learning moments into new evolving understandings (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014). Reflective journaling offered prime insights into these transformations from a global perspective (Craig et al., 2015). The journal provided formative assessment, becoming a powerful tool for learning, although the quality of these reflections usually depended on the directions given and the requirements listed (Marine, 2013). Furthermore, Craig (2015) highlighted the gaining momentum of the use of web based journaling platforms as tools to cultivate reflection.

Post program activities

Post Program activities included written assignments, discussions, and evaluations. Simply being abroad did not mean students completed the program requirements and neither were students guaranteed a high grade for the course (Eckert et al., 2013). As with on site activities, clearly defined expectations up front meant fewer problems when the time comes for assigning grades (Eckert et al., 2013).

Program Evaluations

Evaluating the program and determining whether objectives were achieved and what changes should be made to the program should be the final step (Eckert et al., 2013). These evaluations should come from students, faculty and program leaders, and service providers. Currently, formal and informal instruments have been used to develop program specific questionnaires (Eckert et al., 2013). Faculty leaders should review all components of their program with particular attention to the assessment of the educational value of business and cultural visits, the professional and personal conduct of the students, the engagement of students, and how unexpected events were handled (Eckert et al., 2013). The latter included a range of problems that can emerge. For example, students losing passports, missed flight connections, getting lost, being scammed in currency exchanges or by taxi drivers, getting sick, feelings of loneliness, roommate conflicts, or suffering culture shock (Eckert et al., 2013).

Barriers to Benefits

Unfortunately, while short term study abroad programs may help to send more students abroad, programs led by faculty members or others who may have little or no experience with accepted standards for designing and managing education abroad programs do not experience the same types of outcomes (Institute of International Education, 2009). Students’ worldviews are not guaranteed to be broadened whilst abroad, nor can increased cultural competency be guaranteed for students who participate in study abroad programs (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). The mere fact that students study abroad does not mean they will be successful academically or professionally (Brandauer & Hovmand, 2013).

The assumption that as long as students go abroad they learned the skills and knowledge they need to be successful in a global workforce no longer holds true (Brandauer & Hovmand, 2013). There can be no expectation that a single program could magically transform students (Peckenpaugh, 2014) because students in short term study abroad programs have a brief amount of time and limited exposure to the local culture (Brooking, 2010). Furthermore, students can isolate themselves from the culture (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013) not allowing them to make meaningful progress in developing intercultural competence (Peckenpaugh, 2014). A lack of intentional engagement could lead to the reinforcement of stereotypes or inappropriate behavior issues abroad (Anderson et al., 2016). For students to learn about difference and to develop cultural sensitivity, a good experience and supporting pedagogies and education practices were found to be necessary (Younes & Asay, 2003).

Role of Faculty in Student Learning and Development

The quality of short term programs was dependent on the program leader/faculty’s administration (Brooking, 2010). Students have an opportunity to see faculty in a variety of roles – as a parent, traveling companion, gourmet, and a connoisseur of the arts (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Faculty led study abroad participants articulated the highest rates of everyday learning, possibly indicating that faculty led students recognized both the importance of everyday conversation to learning and the incorporation of the opportunity for learning into the study abroad curriculums (Graham & Crawford, 2012).

Highly effective instructors organize their educational activities in such a manner that they address the four learning modes of experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting, (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012) changing the role they play depending on the stage of the cycle being addressed. Instructors of study abroad programs draw on reflective observation to help learners get in touch with their own experience and reflect on it, helping students organize and connect their reflection to the knowledge base of the subject matter (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012).

Intercultural awareness and development that students might expect to gain from a study abroad were unlikely to without preparation to maximize the benefits of study abroad (Holmes et al., 2015). Faculty impacted intercultural gains in students through the spontaneous and frequent facilitation of reflection (Anderson et al., 2016). Anderson et al. (2016) found that the most effective faculty leaders facilitated intercultural learning for their students by serving as intercultural mentors who supported and guided students through the incidents of cultural discord, as well as intentionally support their group to achieve a healthy intra group dynamic, and created a safe place to debrief. Structured reflection was enhanced when faculty arranged for at least one group debriefing session led by a host country facilitator to expand how students receive support, feedback, and debriefing and to support student development of intercultural competence (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). The faculty’s level of engagement within the program also demonstrated its quality, as a fully involved faculty were in a better position to make minor changes to the program to facilitate a responsive learning environment (Brooking, 2010).

Reflective and Reflexive Activities

Reflection, defined as the focused consideration upon a specific method or level of interpretation, differed from reflexivity (sometimes called critical reflection), the multidimensional interpretation that comes from introspection (Benschop, 2002). To be reflexive supported critical introspection and can nourish reflections as introspection leads to heightened awareness, change, growth, and improvement of the self (Ryan, 2005). In reflectivity, participants reflect on various elements (verbal, nonverbal, feelings, and thoughts) following the action, but to be reflexive, participants must investigate their interactions via introspection as they occur (Ryan, 2005). Reflection made individuals aware of their reality and gives them an opportunity to change that reality (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Reflexivity involves the capability of students to constantly reflect upon, examine, and revise who they are as individuals, as well as what we do in the light of new knowledge. In other words, reflexivity is both a consequence and an attribute of reflection (Rigg, Trehan, Stewart, & Swan, 2008).

According to Rigg (2008), reflexivity ranges in characterization from critical reflection or “thinking about thinking” to more radical conceptualizations concerned with thinking about oneself from within. In a study done by Mathews (2001), attempts were made to find the distinction between reflection and reflexivity. Mathews (2001) found that reflective writing can enhance student’s engagement in reflexivity, however, care should be taken that students’ progress past reflection into reflexion (Mathews, Rivera, & Pineda, 2001). According to Rigg (2008), reflexivity can be engaged through an application of a range of reflective tools, such as journals, critical incident analysis, or repertory grids.

Ensuring adequate time for reflection, discussion, and debriefing allowed students the time needed to deepen their understandings of their experiences which encouraged student development (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). Reflecting on how the experience tied to course concepts and techniques was essential for learning (Eckert et al., 2013). Given the participant’s involvement as an input into each of the parts of the study abroad experience, capturing the participant’s experience with the encounters and how the participant responds to those encounters should be valued (Domke-Damonte et al., 2014).

The type and frequency of reflection within the programs differed; furthermore, the manner in which these components were implemented had an effect on student outcomes and perceived program quality (Brooking, 2010). Reflection established the connection between the academic and the experiential components of a study abroad program (Brooking, 2010). Furthermore, Boyle et al. (1999) asserted students needed the opportunity to explore new ways of learning when studying in a different cultural context. The use of reflection showed an increase of students’ understanding of course concepts and allowed for broader and deeper learning (Brooking, 2010). Study abroad programs without a reflection component demonstrated lower rates of learning compared to programs that included a reflection component (Brooking, 2010).

By understanding the experiential learning process faculty members leading study abroad programs will be more effective at maximizing learning opportunities abroad (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Therefore, students should be encouraged to reflect on and connect their experiences in and outside of the classroom, reflection which in turn leads the student to conceptualize new thoughts and ideas based on their experiences and leads to further action (Brooking, 2010). Formal reflection activities represent a vital role in Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning cycle.

Conceptual Framework

Because of the nature of this study, an experiential learning conceptual framework was used. Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning illustrated that as a student passed through the four stages of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation they acquire, new knowledge, skills, or attitudes that were achieved through engagement in the four modes of experiential learning (Kolb, 1984).

Experiential Learning

Experiential education came from an educational philosophy first articulated by John Dewey, Lewin, Piaget and other scholars, who developed theories of education rooted in and transformed by experience (Lutterman-Aguilar & Gingerich, 2002). Kolb then integrated those philosophies into the Experiential Learning theory, which offered a fundamentally different perspective that combined experience, perception, cognition, and behavior (Kolb, 2005). Due to the holistic approach of human adaptation through the transformation of experience into knowledge, Experiential Learning theory provided a good model for educational interventions in study abroad programs (Peckenpaugh, 2014).

Kolb described the learning through six characteristics. 1. Learning as a process that occurs through experiences. 2. All learning is re learning facilitated by constructing knowledge based on experience. 3. Learning requires the resolution of conflicts which initiates the learning process. 4. Learning is a holistic process of adaptation, the integrated functioning of the total person. 5. Learning results from the transactions between a person and the environment 6. Learning is the process of creating knowledge (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). Figure 1 describes the Cycle of Experiential Learning based on Kolb’s process where experiences become the basis for observations and reflections. These reflections then become abstract concepts of which can serve as guides in creating new experiences from which learning can arise (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012).

The first stage in the learning cycle consisted of concrete experience, upon which the other three stages were built (Kolb, 2005). Within the second stage, reflective observation, an individual built on concrete experience through the reflection and observation of their experiences from many perspectives (Kolb, 1984). This included organized reflection carried out in oral or written form (Brooking, 2010). The third stage, abstract conceptualization, developed out of reflective observation through the construction of ideas based on earlier reflections (Brooking, 2010).

Kolb (1984) believed that students moving through abstract conceptualization created concepts that integrate their observations into logically sound theories. After these new attitudes have been shaped, the individuals can put their thoughts into action (Brooking, 2010).

Individuals in the fourth stage must be able to use these theories to make decisions and solve problems (Kolb, 1984). Students experiencing active experimentation took what they learned and created outcomes that connected their experience in the community to their academic knowledge (Brooking, 2010).

One of the fundamental beliefs of experiential education included that experiences were not educational in and of themselves (Lutterman-Aguilar & Gingerich, 2002). It is the reflection process which turned the experience into experiential education (Joplin, 1995). Although international courses provided experiences, a need existed for a pedagogical frame that allowed rich experiences to be critically analyzed and reflected upon (VeLure Roholt & Fisher, 2013). Experiential learning should integrate action and reflection, as well as an emphasis on understanding learning as an ongoing process of having experiences, thinking about experiences, and then constructing new understandings and questions to take to another experience (Joplin, 1995). Furthermore, experiences should be discussed and then returned to and critically analyzed (Lutterman-Aguilar & Gingerich, 2002).

Learning Space

The learning space needs to be a hospitable, welcoming space that is characterized by respect for all in a safe and supportive environment, but is also challenging and must allow learners to be in charge of their own education (Kolb, 2005). The psychological and social dimensions of learning spaces have the most influence on learning (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012). The different modes of learning could be used to increase scores in the dimensions of responsibility, efficacy, global centrism, and interconnectedness (Stebleton et al., 2013). For a learner to engage fully in the learning cycle, space must be provided to engage in the four modes of the cycle—feeling, reflection, thinking, and action (Kolb, 2005). Study abroad programs are uniquely positioned to offer a rich variety and depth of learning spaces (Passarelli & Kolb, 2012).

Research showed that the integration of experientially based activities provided more meaningful and relevant learning because the effective introduction of experiential learning provided a level of extrinsic motivation to enhance the learning experience (Drake et al., 2015).

Study abroad should facilitate students’ intellectual growth, and contribute to students’ professional development and aid in the educational or professional development of outstanding individuals (Brooking, 2010). The change of environment can be temporarily unsettling, yet at the same time it opened students to the myriad of experiences they encounter and developed knowledge essential for a meaningful learning experience (Drake et al., 2015). The new surroundings, culture, language, currency, etc., helped raise the students’ awareness and attention level to create a learning experience (Babb et al., 2013).

Chapter Summary

Chapter two introduced a historical background of study abroad programs. A brief overview of the different types studyabroad programs, including the rise of short term study abroad programs was also explored. Outcomes of study abroad programs were outlined, focusing on the outcomes of short term study abroad programs. The globalization of curriculum was discussed. The format of study abroad programs was broken down into pre departure activities such as orientations, on site activities such as daily meetings, in country interactions, program activities like written assignments, and daily journals, and post program activities, including program evaluations. Barriers to benefits were also included in chapter two because studies have shown that simply being abroad will give students the skills and knowledge they need to be successful. The role of faculty members was discussed in the context of the impacts faculty had on intercultural opportunities of the students.

As Younes (2003) stated, for students to learn about difference and to develop cultural sensitivity, a good experience and supporting pedagogies and education practices are often required. Reflective and reflexive activates were discussed, paying special attention to the role in the experiential learning process. Chapter two introduced the conceptual framework used for the study, which included experiential learning, Kolb’s cycle of Experiential Learning, and study abroad programs as learning spaces. However, the review of the literature revealed a gap in the literature. Previous literature has not been clear on how faculty members of the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences use reflective and reflexive activities in short term study abroad programs to impact student development.

CHAPTER 3

METHODOLOGY

Chapter one introduced the rise of globalization in American education. Short term study abroad programs, in particular, have been used to foster cultural development in students, among other benefits. However, studies have shown that being abroad was not enough to promote culture learning, and supporting pedagogies and education practices are needed to develop cultural development in students. The objectives of this study aimed to 1) determine the factors that influence the activities faculty members chose to incorporate into their study abroad program, 2) determine which reflective and reflexive activities are perceived as beneficial to student development, and 3) determine the perceived role of faculty members in student learning and development.

A review of research and literature related to the outcomes of study abroad programs and the role of experiential learning was explored in Chapter two. The literature review focused on the historical background, the different types of study abroad programs, outcomes of study abroad programs, the internalization of curriculum, and study abroad used for a learning space. The format of short term study abroad programs, focusing on pre departure, on site activities and post program activities and some of the barriers to benefits students may experience was also explored in Chapter Two, as well as reflective and reflexive activities and the role of faculty members in the learning process.

The following components of the research methodology are discussed in this Chapter: (1) research design, (2) participants and sampling procedures, (3) data collection, and (4) data analysis. To address the legitimacy of the study, issues such as (1) trustworthiness and (2) subjectivity statement have also been addressed.

Research Design

The researcher used a qualitative case study design, consisting of a set of interpretive practices that attempt to make sense of phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them (Creswell, 2012). Qualitative research is the broad designation for the approach that generates, analyzes, and interprets data through non statistical means (Schwandt, 1997). Qualitative research attempts to identify and understand complex variables that cannot be easily measured by talking directly with people and allowing them to tell the stories unencumbered by expectations of findings (Creswell, 2012). Qualitative researchers gather up close information by examining documents, observing behavior, and interviewing participants (Creswell, 2012). Furthermore, relying on the researcher and the participants as the instruments to gather the data (Prasad, 2005).

A case study research design explores a real life case through detailed, in depth data collection involving multiple sources of information (Crotty, 1998). Case study research allows researchers to answer questions like “how” or “why”, particularly when the researcher has little or no possibility of controlling the events (Yin, 2013), unclear boundaries exist between the phenomenon and context, or when using multiple sources of evidence is desirable (Schwandt, 1997). Yin (2013) states that selected cases should reflect characteristics and problems identified in the underlying theoretical propositions or conceptual framework. For this study cases were chosen because the phenomenon (use of reflective and reflexive activities for student development) could be clearly identified in the study abroad programs with one case study providing a contrasting result.

An interview conducted with faculty members in their natural environment was the collection protocol used by the researcher (Prasad, 2005). Qualitative interviewing involves asking questions and getting answers from participants (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006). Qualitative interviewing takes a form as structured, semi structured, in depth, or unstructured (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006). For the purpose of this study semi structured interviews was the main method of data collection. The semi structured interviews in this study aimed to understand the experiences of the participants and the meaning that makes their stories rich (Prasad, 2005). Semi structured interviews were conducted with faculty members of the University of Georgia’s College of Agriculture and Environmental Education who direct study abroad programs. Document analysis was also conducted through an examination of study abroad program’s syllabus and/or program schedule.

Participants and Sampling Procedures

Participants

The research sample consisted of three instrumental study abroad programs purposefully selected to illustrate how reflective activities are conducted. Participants were selected if faculty conducted study abroad programs for more than five years, incorporated reflective and/or reflexive activities, and had a generally positive reputation. The original objective was to examine how faculty members use their study abroad programs to encourage student learning and development. Questions arose that faculty members might not prioritize student development and only focus on technical academic content, therefore the scope of the study was narrowed to faculty members who incorporate reflective or reflexive activities into their study abroad curriculum.

Sampling procedures

Purposive sampling was conducted when choosing the original participants. A search of study abroad programs at the University of Georgia Office of International Education website showed four programs that incorporated reflective or reflexive activities into their program. Faculty members were selected because they provide valuable information to the investigation (Schwandt, 1997). Recruitment emails were then sent to those professors (APPENDIX B). After the interviews participants were asked if they could recommend another faculty member who used reflective or reflexive activities in their study abroad programs, however, no new names were identified.

Data Collection

The primary method of data collection was semi structured interviews. Additionally, document analysis was conducted of program syllabus and schedules as well as documentation of their program planning documents (rationale, planning process, benefits to the UGA community and responsibilities). During the interview, faculty members were asked to describe the nature of the activities they conduct during their study abroad programs. Interviews provided thick descriptions of the way faculty members use reflective and reflexive activities in their programs. The findings in interviews were correlated by examining documents. The program syllabus, as well as the program plan, provided evidence that faculty members prioritized student development when considering their study abroad program. Program syllabus showed how faculty members incorporated activities into their program in terms of duration and frequency.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to conducting the study (APPENDIX A) to comply with University of Georgia guidelines. The researcher then contacted the faculty members via a recruitment letter sent to the email addresses they provide on their program website. Faculty members who volunteered to be interviewed were then contacted for more information about the study and to receive a consent form (APPENDIX C) via email. Interviewees were also asked to provide dates to schedule an interview that lasted approximately 60 minutes. Before the interview began the research went over the consent form and asked participants to sign the form before proceeding with the interview.

Primary Interview

Based on the literature reviewed and the conceptual framework described in Chapter two an interview protocol was developed and reviewed by the graduate student committee members (Appendix D). The main open ended questions asked to participants were the following:

1. What does a curriculum abroad offer that a university based program does not?

2. What kind of pedagogical objectives do the activities in study abroad programs incorporate?

3. What is the role that reflective or reflexive activities within the curriculum of study abroad programs?

4. What benefits arise from incorporating those activities that would otherwise not be available?

5. What challenges have been faced in implementing activities in the study abroad program?

Interviews were conducted in the faculty member’s office at their most convenient time. As stated in the consent form, interviews were audio recorded, transcribed by the researcher, and then deleted. The researcher saved each consent form and the notes packages in a locked cabinet located in the researcher’s office, digital copies of the interview and notes were kept on password protected computers. The individual interviews lasted between 70 and 80 minutes, depending on interviewees. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by the researcher and assigned an identification number as well as a pseudonym to preserve confidentiality (Table 1).

Table 1. Identification Numbers to Interview Transcriptions and Corresponding Pseudonyms

| Transcription name | Identification number | Pseudonym |

| Verbatim transcription one | R1 | Roger |

| Verbatim transcription two | R2 | John |

| Verbatim transcription three | R3 | Sam |

.

Data Analysis

The data analysis software ATLAS.ti version 7 was used for thematic coding and categorization of the interview data and document analysis. ATLAS.ti is an analytic process software program that allowed for the development of coding, organization of the data, hyperlinking, and the retrieval of coded segments (Silver & Lewins, 2014). The thematic coding process involved selecting fragments from the sources of information (i.e., interviews, documents) and transforming them into quotations (Friese, 2014). Using ATLAS.ti allowed for the exploration of relationships between units of the discourse rather than between conceptual constructs (Friese, 2014), keeping the researcher close to the data and close to the voice of the participant (Silver & Lewins, 2014). After identifying the codes, constructs were created which developed into a framework of thematic ideas (Gibbs, 2007).

Interpretative Analysis

Gibbs (2007) described different approaches to thematic coding and such as interpretative phenomenological analysis, grounded theory analysis, template analysis, and framework analysis. In this study, an interpretative analysis was conducted.

The interpretivist paradigm arose in educational research field beginning in the late 1970s, showing strong influences of anthropology which aims to understand other cultures from the inside (Taylor & Medina, 2013). The interpretivist paradigm was also heavily influenced by hermeneutics, the study of meaning and interpretation in texts, and phenomenology, which advocates the need to consider human beings’ subjective interpretations as the research starting point (Mack, 2010). Interpretivism was developed as a reaction with positivism, emphasizing the ability of the individual to construct meaning (Mack, 2010). Interpretivists seek to understand by learning to looking through the individuals eyes’ (Taylor & Medina, 2013). Interpretivist’s believe one can never be objectively observed from the outside rather one must be observed from inside through the direct experience of the people (Mack, 2010).

Interpretivist’s ontological assumptions state reality is seen by multiple who interpret events differently and create multiple perspectives of an phenomenon (Mack, 2010) and it is the role of the researcher to understand, explain, and demystify the reality through the eyes of different participants (Cohen et al, 2007, p. 19). Furthermore, interpretivist researchers seek to understand rather than explain (Mack, 2010) through trustworthy and authentic ethnographic methods such as informal interviewing (Taylor & Medina, 2013).

One of the limitations to interpretive research is the lack of scientific procedures for verification, therefore results cannot be generalized a wider population (Mack, 2010). However, Lincoln and Guba (1985) created quality standards of trustworthiness and authenticity which are different but in line with the values of the validity, reliability and objectivity standards of positivism. The standards set by Lincoln and Guba are arguably the most well known and coherent of qualitative research (Taylor & Medina, 2013). Another criticism of interpretivism is the lack acknowledgement of outside influences on knowledge and reality such as political and ideological stimulus (Mack, 2010). However, one of the strengths of interpretivist research is the depth and breath of familiarization with the data which informs the researcher about the phenomenon being studied, instead of the researcher’s own preconceptions (Mack, 2010).

Interpretivism enables educational researchers to build rich and deep understandings of the life world experiences of teachers and students and of the cultures of classrooms, schools and the communities they serve (Taylor & Medina, 2013).

Phase One: Transcription

Audio recordings can be beneficial in assisting interviewers to fill in blank spaces in their field notes and check the relationship between the notes and the actual responses, potentially reducing interviewer bias and allowing interviewers to reflect on the conversation to ensure that the meanings conveyed by participants are adequately represented (Halcomb & Davidson, 2006). Given the emphasis on exploration and inquiry of human phenomenon, interviews have traditionally been a method of data collection associated with the qualitative paradigm and verbatim transcription of interview data an integral part of the analysis and interpretation of verbal data (Halcomb & Davidson, 2006). Verbatim transcription refers to the word for word reproduction of verbal data, where the written words are an exact replication of the audio recorded words (Halcomb & Davidson, 2006). In this study, the researcher personally transcribed the interview audio recordings one by one, without outsourcing to a professional transcriber.

Phase Two: Familiarization and Coding Interviews

The verbatim record of the interview is beneficial in facilitating data analysis by bringing researchers closer to their data, allowing the researcher to become immersed in the data and begin the familiarization of possible codes, constructs, or ideas about the phenomenon under investigation (Halcomb & Davidson, 2006). Becoming familiar with the interview transcriptions, the interview notes, and the reflective notes written in the reflective journal is vital to interpretation (Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid, & Redwood, 2013). During phase two the researcher read the interview transcriptions, the interview notes, and other documentation carefully and in depth to better prepare for the upcoming data analysis.

The researcher chose ATLAS.ti software to facilitate coding. A Hermeneutic Unit was created to provide the space that contains the project, encompassing everything in the project such as primary documents, quotations, and codes (Friese, 2014). Primary documents such as interviews, syllabus, and trip schedules were then uploaded into the hermeneutic unit.

Analysis of data was based on Yin’s (2013) explanatory analytical techniques. Case study data was compared empirically for patterns of causal links. Findings of the initial case were then compared and revised for expected outcomes or rival explanations. After becoming familiar with the data the researcher applied a label (code) to the quotations in the passages that were essential to the phenomenon under investigation (Gale et al., 2013). The researcher then arranged the codes into categories that would later become the constructs. Next, the researcher arranged the codes into categories that would then form the constructs of the new themes based on the data. As constructs emerged, the researcher compared them constructs found in the literature review to better label them and to develop finalized themes.

Following data analysis, the researcher sought an external reviewer to provide feedback on codes, categories and themes for validation purposes and to reduce researcher bias. External researchers provide independent feedback about the coding process for validation purposes and to ensure that one particular perspective does not dominate (Gale et al., 2013).

Trustworthiness

Qualitative inquiry represents a legitimate mode of social and human science exploration without apology or comparisons to quantitative research (Creswell, 2012). Criteria used to judge the quality of qualitative inquiry is largely based on Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria for trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). The researcher sought to address trustworthiness through a rigorous process of data collection and analysis, and the external reviewing.