Reusing Empty Properties as a Solution to Scotland’s Social Housing Shortfall

Info: 9280 words (37 pages) Dissertation

Published: 17th Nov 2021

Abstract

The aim and objectives of this dissertation are to research the problem of long term empty homes within Scotland, investigating regeneration for social housing and exploring the solutions available to local authorities in tackling the issue.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

1.1 Rationale

There is an undeniable housing crisis in Scotland that is becoming an increasing priority for the government and local authorities. Social housing in particular has severely decreased since the introduction of the right to buy scheme in 1980 which has resulted in the overall loss of nearly 500,000 local authority homes from the social rented sector (Shelter Scotland 2017). Glasgow has been particularly affected after the City Council transferred its entire stock of 81,000 public housing units into the hands of the Glasgow Housing Association (GHA) in 2003. GHA’s significant demolition programme of large numbers of social rented properties (in particular multi storey high-rise flats) carried out in the past 15 years has created a severe reduction and availability of social/below market rent stock and affordable housing in the city. (Glasgow City Council 2017)

The Scottish Government has pledged to commit over £3bn across Scotland over the next 5 years (2017-2022) to fund the delivery of 50,000 affordable homes, 70% of which will be for social rent.(Scottish Government 2017) Glasgow City Councils housing supply target for the strategy period has increased from the 12,500 figure quoted in the consultation draft to 15,000, the increase being specifically for social rented (SR) and below market rent (BMR) properties, with a minimum target of 7,500 properties in this category. (Glasgow City Council 2017)

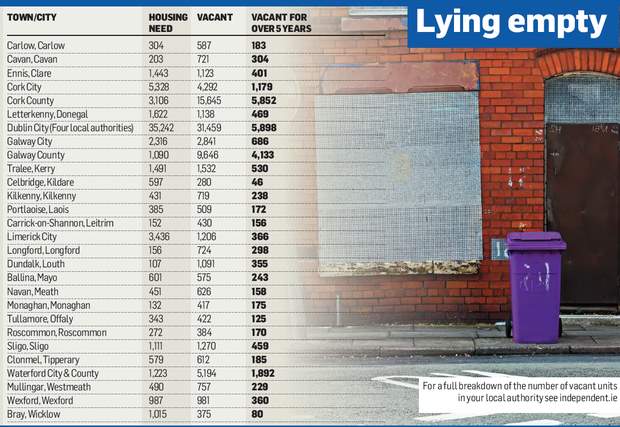

New development however is simply not meeting the increasing demand and a large amount of the properties being delivered are homes for sale that are not accessible to a large proportion of society introducing huge affordability challenges. Availability and affordability of housing is a vital foundation in a sustainable economy and the deficit requires a substantial reform in the construction industry to meet the housing needs of the country’s growing population. Glasgow in particular has developed a serious issue when it comes to the availability of affordable/social housing and the city is suffering from an unacceptably high level of homelessness. The latest government figures also show over 200,000 families are currently on accommodation waiting lists in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2017) (GHA, 2017). Yet statistics also show that in the last decade the countries number of long-term empty homes has nearly doubled, from around 20,000 in 2007 to almost 40,000 in 2017 (Scottish Government, 2017).

Yet it is a paradox that the city has a copious amount of empty, derelict and abandoned properties going to waste. In a recent interview with Barry Sheridan, the Empty Homes Officer (EHO) for Glasgow City Council, he stated that there are currently nearly 3000 private homes in Glasgow that have been empty for more than 6 months.

No one gains from an empty property, there is no rental income being generated for the owner, there is generally a reduced amount of taxation that the local authority could be receiving, the utilities companies are not making any revenue, the value of adjoining properties are reduced and the local economy does not benefit from the spending power of the potential residents. The Scottish Empty Homes Partnership estimate that long-term private empty homes across Scotland are worth a combined total of £4.5 billion. (SEHP 2017), thus the question can be posed, with so many people unable to find social housing or even shelter, why are there nearly 40,000 long term empty dwellings going to waste in Scotland alone, and could the reuse of these properties be part of a holistic solution to the social housing shortfall?

1.2 Focus of the Study

This research will look to consider empty property regeneration as a sustainable way to help meet Scotland’s housing demand and help alleviate the pressure to develop on greenfield sites. An investigation into the plausibility of converting the countries copious amount of empty, derelict and abandoned buildings into social housing stock or affordable homes will be carried out. The research will investigate the wider picture to establish the reasons that dwellings fall empty and fail to return to use and identify the problems associated with empty properties. The initiatives the Scottish Government has took to increase the reuse of empty properties to house homeless or low-income households will be identified. The research will also consider what enforcement powers local authorities possess to deal with the issue of empty properties and if new legislation is needed to increase their reuse as social housing stock or affordable homes. This concept was developed through the writers concerning interest and moral dissatisfaction with the number of wasted real assets in Glasgow despite the fact there are still thousands of people being refused the fundamental human right to housing.

1.3 Aim

The primary aim of this dissertation is to investigate the regeneration of Glasgow’s long term empty properties into social housing stock or affordable homes.

1.4 Objectives

This study intends to achieve this aim through a number of objectives:

- Investigate the extent of Glasgow’s social housing shortage.

- Investigate the reasons properties become empty and fail to return to use.

- Identify the associated social/economic problems.

- Identify the Sottish Governments empty property initiatives.

- Investigate local authority response to empty properties and enforcement options.

- Compare legislation and attitude towards enforcement in Scotland and England.

- Consider the effectiveness of current and if specific legislation is needed.

1.5 Outline of Dissertation Structure

Chapter 1 – Introduction

The first chapter includes a general introduction to the writer’s chosen topic, and outlines the aim and objectives of the research being undertaken. This chapter highlights the methodology applied in the research and explains the techniques used to gather the information. The structure of the document containing a summary of each chapter is also included.

Chapter 2 – Literature Review

The second chapter of this paper will review the literature available relating to the issues of social housing and empty dwellings. The literature review will consist of library searches, computer data base searches, analysis of government publications and statistics data, and researching news articles. The review will include facts and figures obtained during the writer’s attendance of Shelter Scotland’s Empty Homes Conference 2017, which formed an integral part of the research. The review will summarise the Scottish Government, local authority and housing associations policies surrounding the management of empty homes. The research will also look at what enforcement methods are available to local authorities to deal with empty houses and identify any issues or a need to reform legislation.

Chapter 3 – Methodology

The third chapter will explain the author’s choice of methodology and outline the research methods implemented in the report including quantitative data collection and qualitative research techniques.

Chapter 4 – Results and Analysis

The fourth chapter will contain the data collected during the research phase of the dissertation and the results of the analysis carried out. This will include the explanation and interpretation of the quantitative and qualitative research results.

Chapter 5 – Conclusion and Recommendations

The final chapter will provide a conclusion to the research topic and will explain how the author achieved the aims and objectives set out at the beginning. Recommendations will be made as to whether the author feels there is a need to reform local authority legislation surrounding empty homes and whether the Scottish Government can improve its initiatives on reusing empty properties.

Chapter 2 – Literature Review

2.1 Scotland’s Social Housing Shortage

Scotland has developed a serious issue when it comes to the availability of affordable/social housing and the country is suffering from an excessively high level of homelessness. In the past acquiring a council house was not considered a difficult undertaking however in Scottish cities today it can seem like an almost impossible task. Latest government figures show there are currently over 162,000 applicants on local authority housing lists (Scottish Government, 2017). However, this figure does not include the six councils (Glasgow, Inverclyde, Argyll and Bute, Dumfries and Galloway, Western Isles, Scottish Borders) that transferred their entire stock to housing associations and the Scottish Government has been accused of underestimating the social housing demand (Barnes 2017).

During a recent interview with the writer, an employee for Glasgow Housing Association stated that there are currently more than 35,000 people on their accommodation waiting list with some applicants waiting years to be housed (Glasgow Housing Association). Recent analysis of the Scottish Housing Regulator gave a “conservative estimate” of the total number of people on accommodation waiting lists in the remaining five local authorities stood at around 40,000. This bring the countries total number of social housing applicants to over 240,000 more than 40% than stated in the official government figures.

Scotland’s biggest homeless charity, Shelter Scotland, estimates there to be between 5000 and 6000 people living on Scotland’s streets every day (Shelter Scotland 2017) with official figures showing at least 4,751 people slept outside overnight in 2017, an increase of 15% from 2016 (Scottish Government 2018). The Scottish Governments local area statistics show 35377 homeless applications were made between November 2016 and 2017, and as at 31st of November 2017, 10,899 households were in temporary accommodation, an increase of 2% (Scottish Government 2017). Although mental health, substance abuse and family and relationship breakdowns are the main reasons behind homelessness (Shelter Scotland 2016), an acute lack of suitable and available social housing is likely contributing to these unacceptably high figures.

2.2 Empty homes

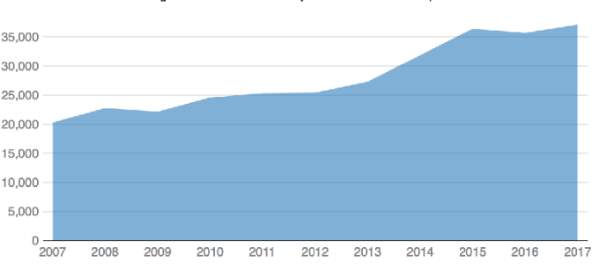

Government figures show the total number of homes considered long-term vacant in Scotland has risen to 37,135, an increase of more than 80 per cent since 2007 when the total stood at 20,328. (Scottish Government, 2017) However it is important to recognise the limitations of official statistics on vacant dwellings. These figures derive from the council tax list the purpose of which is not to count empty homes. The council tax data does not class derelict properties (one where no one could reasonably be expected to live in) as dwellings therefore the official empty homes figures do not include properties that have been removed from the council tax list due to their state of repair. This data also excludes properties where there is an exemption from paying council tax (i.e. repossessed by bank or mortgage lenders), thus the actual number is considered to be significantly higher. Nonetheless, these figures are a good starting point.

Long-term empty homes in Scotland over the past decade –

Source: Scottish Government

Derelict properties are often of particular concern to local people as their poor physical state may have a direct detrimental impact on nearby properties and the neighbourhood. Derelict properties often stand out as eyesores and symbolise waste in the face of so many people being priced out of decent housing across England. Many derelict properties can be, and are being, brought back into use. For all these reasons it is important that strategies to tackle empty homes are broad-based and not just focused on properties that are recorded and counted as empty in the official statistics.

2.2 Reasons Properties Become Empty

There is a common misconception that it is simply a financial issue that so many properties are being left empty, and that no rational person would just let their asset go to waste. However previous studies have found the individual reasons dwellings can become empty are as varied as the properties themselves with barriers such as time, skills, owner’s attitude, emotion, relationships and legal issues often all intertwining resulting in properties being left empty for years. (Lucas, C 2014) In 2016 a national empty homes helpline was set up by the Scottish Empty Homes Partnership in attempt to help reduce Scotland’s growing number of unoccupied properties. When asked why the property was unoccupied the top two reasons given by private homeowners were; unwilling to/fear of becoming a landlord, and bought for capital gain/waiting for property market to improve. (SEHP, 2017) https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2014/jan/03/mortgage-lenders-restoration-empty-homes

The following results are from a survey carried out by Ipsos MORI on the reasons for homes being empty in England:

Source: Ipsos MORI

http://www.emptyhomes.com/assets/empty-homes-in-england-final-september-2016.pdf

2.2.2 Housing Market

There are vast numbers of properties lying empty that have been purchased for speculative reasons by developers and investors. Many wealthy individuals and organisations buy up properties during dips in the market where it is possible to make a considerable profit simply by waiting to resell the property (Davies, 2017). These investors are relying on capital appreciation to create a return, so in order for the initial investment to be worthwhile they must wait for the market to pick back up. (Hunter, T 2017) These owners frequently leave the properties unoccupied to avoid the costs and complications that come with letting a property, repairs and administration etc. according to property expert Henry Pryor, this is contributing to the number of empty properties in the new-build market as many buyers will pay a premium for pristine apartments. “Just as they would feel when buying a new car, some buyers don’t want to live in a second-hand home, and this applies even when they’re buying a place that’s five years old”. This phenomenon was reported on by STV News and referred to as buy-to-leave, where investors have no intension of ever letting out their properties as their only goal is capital appreciation. (Vevers, 2017)

2.2.1 Disrepair

Renovation costs can be extremely high. Often, the owner of a dilapidated property may have the desire to live in it or rent it out, but finds the necessary work either too expensive or overwhelming in scale. There may well be practical and financial assistance available, however, it is often the case that owners of empty properties are either not aware of these initiatives or there may be other barriers that prevent them from taking advantage of the help available. In many surveys, disrepair is stated as the commonest reason why properties are left empty.

2.2.4 Other common

A lack of motivation, knowledge or insurance to cover a damaged home were also often quoted as the reason a property had been left empty for six months or longer.

Some empty home owners admitted they had an emotional attachment to their empty homes and found it hard to let go of them – sometimes for decades on end – because they had grown up there.

One of the more unusual reasons include owners who do not realise that they have inherited a property after a relative passes away and come sometimes be years.

2.3 Associated Social and Economic Problems

The obvious problem that an indispensable asset is being left to waste and further restricting the housing supply can overshadow the surrounding social and economic problems that are brought about as a result of empty houses. Long term empty houses can cause antisocial behaviour and increase crime in the surrounding area. They often fall victim to vandalism and fly-tipping, but can also pose more serious potential risks, such as been used to cultivate and sell drugs or being taken over by addicts (Scottish Government). Homes lying empty in communities can cost an average of £7,500 a year through lost rent, lost council tax and the cost of securing or making safe the property.

This figure doesn’t take into account other financial burdens associated with empty homes such as anti-social behaviour, crime, and lost spend in the community from potential tenants (West Dunbartonshire Council, 2016). In July 2016 the Scottish Empty Homes Partnership carried out a YouGov survey that looked at the public’s attitude towards the problem.

The results show that 75% of Scottish adults believe that empty homes cause anti-social behaviour, 54% reported a decreased sense of safety caused by empty homes, and only 3% thought empty homes cause no problems in communities. (SEHP, 2016) Another poll found that only 20% of people in Scotland think local authorities are doing enough to reduce the number of long-term empty homes in their area. (Shelter Scotland, 2016).

These surveys highlight the public’s concern surrounding empty homes in their communities and that the people of Scotland are not satisfied with the action and initiatives currently being taken to tackle the problem. The fact that only 3 % of Scottish adults think empty homes cause no problems suggests there is strong support from the public for councils to view this issue as a priority.

Effect on surrounding properties

Instances of empty homes are not simply a matter of concern to those who own them During the writer’s attendance of the Empty Homes Conference 2017 a recurring topic of discussion was the reductions in local property values observed as a result of properties being left empty and poorly maintained. Dilapidation problems such as damp and dry rot can often arise along with the possibility of attracting vermin. These problems can then spread to neighbouring properties, which is a particular issue when the owner of the house is uncontactable or the property is abandoned. (EHC 2017). This not only raises concern for the health and safety of the local residents but also how the issue affects the value of their homes. Research shows where there are empty properties located it can considerably reduce the value of the houses in the surrounding area. In 2009 Haart Estate Agents carried out research into the impact an empty home can have on the local market value. The results revealed that the presence of an empty dwelling/dwellings outweighs the negative impacts of being in the proximity of a flight path or close to a public bar with a late licence. (Nurton, J 2009) The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors also carried out research that estimated properties adjoining poorly maintained empty homes can be devalued by as much as 18 %. (RICS) (National Archives)

Impact on taxpayers

Empty houses are also costing the taxpayer money. Councils can be paying over £400 for an empty property to be boarded up and made secure, some councils have even resorted to increasing the police presence or paying for security around some the worst hit areas of derelict houses in order to prevent illegal activity occurring. (Shelter Scotland 2016) This is a ludicrous and unacceptable drain on public resources that could potentially and deservedly be spent on reusing these houses.

Case Studies

This property in South Ayrshire has been empty for over 4 years. Council officers have made numerous attempts to engage in a meaningful way with the owner’s son who is responsible for her estate though none have succeeded. The property has severely deteriorated, there is damage to the soffits and fascias which are rotting due to lack of repair, the gutters are overflowing and the neglected garden is now completely overgrown. Neighbours have also complained to the council about the property attracting vermin. The son was engaging with council officers briefly for a time but he has now fallen off the radar. 31 potential buyers have been matched with this property.

Case study provided by Lesley Cockburn, Empty Homes Officer, South Ayrshire Council.

This property in East Ayrshire has been lying empty since 2008, the windows have been smashed and the interior is in a poor state of repair. causing problems to the adjoining property owners.

The owner has been contacted however they are uncooperative and reluctant to rent or sell the property.

It is unknown how long this property in Perth & Kinross has been left empty. Again neglect has resulted in deterioration of the exterior and the garden becoming completely overgrown. The interior has been severely vandalised over the years and after been set on fire in 2012 the council was forced to board up the doors to prevent local kids from getting access. The owner of the property is unknown and can’t be traced.

This tenement flat in Port Glasgow has been left empty for the past 5 years. It is a magnet for anti-social behaviour and has been broken into several times by drug users and homeless people. disgruntled local residents to applied to Inverclyde Council to reuse the empty flat as a base for a food bank. It was proposed that two bedrooms would be used for storage and collection and a third bedroom and the lounge would be used for office and administration but this had to be refused (Inverclyde)

2.4 Sottish Governments Empty Property Initiatives

The Scottish Empty Homes Partnership is a government funded organisation that works with councils to help develop policies and processes to bring private sector empty homes back into use. It was set up in 2009 following the

In 2016 the Scottish Government appointed 8 national outcomes for local authorities to meet:

- We live our lives safe from crime, disorder and danger.

- We live in well-designed, sustainable places where we are able to access the amenities and services we need.

- We have strong, resilient and supportive communities where people take responsibility for their own actions and how they affect others.

- We value and enjoy our built and natural environment and protect it and enhance it for future generations.

- We reduce the local and global environmental impact of our consumption and production.

- We have tackled the significant inequalities in Scottish society.

- We have improved the life chances for children, young people and families at risk.

- Our public services are high quality, continually improving, efficient and responsive to local people’s needs

(Scottish Government 2016)

The Scottish Conservatives have called for a mixture of new incentives and stronger regulation to be introduced to bring more properties back into use. Housing spokesman Graham Simpson said: “Throughout their decade in government the SNP has seen empty properties soar, taking valuable properties out of use. “For the thousands of people waiting for housing this latest increase in empty properties will feel particularly frustrating.

A spokeswoman for the Scottish Government said: “We agree that empty homes can be a blight on communities and are a wasted resource at a time when people across Scotland need homes. “New powers introduced in 2013 allow local authorities to apply a council tax levy on long term empty properties to encourage private owners to bring them back into use.

“Ministers have committed to doubling funding for the Partnership for the next three years. This provides support for a network of Empty Homes Officers who help private owners return their houses into homes.”

By addressing the problem with empty properties it could contribute to meeting several of these.

Issues with current scheme

As part of the government’s national empty homes programme many local authorities offer repair and lease schemes to bring empty properties back into use. Under these schemes an owner can sign their property up to a housing association which refurbishes it using government money that is recovered by leasing the property for a number of years.

Many empty properties have mortgages secured on them, but currently most lenders are refusing permission for their borrowers to enter into lease and repair schemes

Sticking points relate to lenders’ terms, tightened following the financial crash. These commonly prevent a property being leased to someone in receipt of housing benefit, while the schemes are designed to provide affordable housing for those in highest need. Lenders only permit one-year assured shorthold tenancies, while under the repair and lease scheme owners are required to agree to a minimum term of two years (often five or more) to cover the loan period.

There has also been some confusion from lenders as to where the repair and lease loan sits in the hierarchy of charges secured against the property. The loan is in fact placed as a second charge with the banks retaining their position as the priority creditor.

While this major structural issue is not being addressed by the government, the Empty Homes Network (a partnership of empty property practitioners from local authorities) has been working with the Council of Mortgage Lenders and lenders themselves to find a way to bring properties back into use. They have been working to draw attention to the scale of the problem nationally, as well as providing detailed guidance outlining the positives of these schemes for lenders.

2.5 Local Authorities Response to Empty Dwellings

There are currently no specific statutory requirements on local authorities with respect to bringing empty properties back into use. It is the responsibility of each authority to determine their approach and priority towards reusing empty homes according to the local needs and priorities.

2.5.1 Homes Officers (EHO)

There are 21 local authorities in Scotland with a dedicated empty homes officer. applying creative thinking for traditionally harder to bring back into use properties. However, there is still a challenge to influence the remaining councils to understand the importance of empty homes work and recognise the difference a dedicated officer can bring. This is difficult given the reduced budgets and pressures local authorities are currently faced with.

2.6 Enforcement and Other Options Available to Local Authorities in Scotland

2.6.1 Enforcement

Unlike in England where local authorities have Empty Dwelling Management Orders, there is currently no specific power that Sottish local authorities possess to take over the management of an empty private home. (Scottish Government 2016),

Example case stories from Empty Homes Officers:

“We had an issue with a property that had been empty since 1999 and was in a serious state of disrepair. The council spent thousands of pounds repairing the property and stopping it from causing further damage to the two adjoining properties. Thousands of officers’ hours were also used chasing the owner and trying to deal with the state of the property. The council were reluctant to use CPO as they had already spent a large amount of time and resource on the property, and has also had bad experiences using it previously, when the order had not been granted, despite all the effort put in.”

“a first floor flat in the centre of town which has been empty for 14 years. The elderly resident of the ground floor flat struggles to cut the grass on the entire garden whereas she is only responsible for half of the rear garden. Lengths of guttering are hanging off the building which should be common repairs. When I last stopped to look at this flat, a builders van pulled up to ask if the property was on the market. There is strong demand for this type of property from either a developer or an owner occupier”

“The property was a private let and as far as I can tell from the documentation it has been empty since 2008. We have lettered the owner constantly and went to the extent of having a letter hand delivered by an officer from another local authority. At the time of the delivery of the letter the owner spoke to the officer, she explained that her husband dealt with all the finances and he works away. She said that the property was left in a poor state by the previous tenant and they haven’t done anything with it. I have sent the empty homes information but have still had no response. Building control have advised that they do not have any powers available to deal with this property.”

In England

Empty Homes Officers have recourse to both Empty Dwelling Management Orders (to take over the lease of an empty home for up to 7 years), and Enforced Sale (under the Law and Property Act 1925). There are issues with both of these powers including long bureaucratic processes (Empty Dwelling Management Orders) and the requirement for there to be a debt against the property (Enforced Sale) that make them less than desirable for the Scottish context. However what they do offer, that Compulsory Purchase at the moment does not, are powers that councils are actually willing to pursue for single empty homes. The end goal of course is to not have to use the power. However having a power that the council feels confident it could follow through on if needed has been shown to make the other steps in the process above – especially those around negotiation and problem solving with owners – more effective.

Empty Dwelling Management Order

Empty Dwelling Management Orders (or EDMOs) were introduced by the Housing Act 2004 which give the local authority management control of an empty property and the power to let it for seven years, without taking ownership.

The background to the introduction EDMO was a perceived need for a mechanism to return empty dwellings to use that would complement the existing strategies of housing management. Local authorities already had far reaching powers and options available, and were being encouraged by central government to address the problems associated with empty dwellings.

5.2 ‘Positive Ripple Effect’

Local authorities in England have reported that a positive ‘ripple’ effect is often observed after successful intervention opdm 2005

Then problem properties are targeted with enforcement, or when the owners carry out renovation work, the effects are not just witnessed on the target properties. Those properties in the immediate area also show signs of improvement. (ODPM 2005) Word gets out about the actions of the local authority, either by word of mouth or through publicity and other property owners take action without intervention from the council, spurred on either by the fear of council enforcement or a general feeling of well-being and optimism.

http://www.johnpullen.co.uk/uploads/1/9/3/0/19305517/explanatory_memorandum_to_si_367.pdf

CPO

Under powers given by central government to local authorities and other statutory bodies such as national parks and development agencies, it is possible for them to apply for compulsory purchase orders (CPO) on land (and property) provided that certain criteria are met.

“Compulsory purchase powers are provided to enable ‘acquiring authorities’ to compulsorily purchase land to carry out a function which parliament has decided is in the public interest”(ODPM – 2004)

CPOs are used as one of the enforcement tools of a number of pieces of primary legislation such as Housing Act 1985 and Town and Country planning Act (1990).

The Scottish Empty Homes Partnership has also received feedback from numerous councils who have highlighted the need for more empty homes enforcement tools in Scotland. They mainly raise concern about both the cost, timescales and risks of pursuing a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO).

“Time taken to carry out searches, advertise, negotiate with owners if we can find them, prepare a statement of reason, liaise with Scottish Government etc. The process on average takes more than 2 years which can be delayed further if owner appeals the CPO or appeals the valuation and we have to go to a PLI or a Land Tribunal. The whole process in some cases have taken up to 5 years.” – Duncan Thomson, Group Manager of Private Sector, Housing & Regeneration Services, Glasgow City Council. (SEHP)

Through discussions with Empty Homes Officers more specific issues with using Compulsory Purchase have also been raised including: – No clear guidance on what constitutes reasonable efforts to contact or engage with an owner before pursuing Compulsory Purchase. – The requirement to pay market price to the owner represents a direct cost to the council which may not be able to be recouped.

2.6.2 Council Tax Powers

In April 2013 legislative changes were put in place that allow local authorities in Scotland the discretionary power to impose an increase of up to 100% of the relevant council tax rate on long-term empty homes (properties that have been empty for more than 12 months) unless it is being actively marketed for sale or for let. (Scottish Government 2013)

2.7 Property Regeneration Compared to New Builds

2.7.1 Financial aspect

When looking at the financial elements of reusing empty homes and new build the value for money is considerable. The Empty Homes Agency in England has estimates refurbishing an empty home costs an average of £6,000 – £25,000. Compared to the average cost of a new build home in Scotland of £100,000 +. Existing infrastructure and local services will already be in place so there is no need in further investment when bringing an empty home back into use.

2.7.2 Sustainability

The Empty Homes Agency in England carried out research showing that over the short term refurbishing empty homes produces less carbon dioxide emissions than building even environmentally friendly designed new builds. (EHA 2015) New build gives rise to 50 tonnes of Co2 per house; refurbishment 15 tonnes. Empty properties already exist, so the resources needed for new build are not required =

A new building that is 30% more energy efficient than the average building could take 10 to 80 years to overcome the negative carbon impact that comes with new construction versus renovation when you factor in having an existing building and infrastructure. There is an immense amount of energy and CO2 locked into existing buildings from the foundation, materials, energy to make new materials, transport materials, etc. that provides a savings in carbon dioxide compared to the demolition (energy to destruct and haul away) of an existing structure and the creation of a brand new building. http://ecovisionslc.org/renovation-vs-new-construction/

Chapter 3 – Methodology

3.1 – Introduction

The methodology section relates to how the author has planned to achieve their objectives of research (Breach, 2009). The chapter looks at the different ways in which research can be carried out. Several different methods can be implemented to collect and analyse research data, the method that prevailed as most suited was utilized to obtain and collect the necessary data needed in the construction and delivery of this dissertation.

3.2 Rationale for research

3.3 Research Strategy

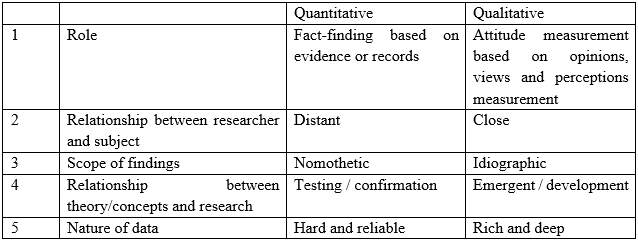

The two main methods of research for a topic are those of qualitative and quantitative research (Naoum 2012).

3.3.1 Qualitative and Quantitative Research – Comparison

In

“The difference between quantitative research and qualitative research is rather like the difference between counting the shapes and types of design of a sample of green houses as against living in them and feeling the environment” (Naoum, 2012)

Bryman 1998 expresses his opinion of the main comparable differences between qualitative and quantitative research methods shown in the table below –

(Source: Quantity and Quality in Social Research, Bryman 1998)

There is no one correct method of data collection, the data collection method is used should be determined by what the author is looking to achieve throughout the research project.

The information collected and subsequent research carried out will highlight the extent of the problem and gather views from local authorities on the types and numbers of empty properties, identify their plans for reuse, assess how effective initiatives have been, look at the constraints of current legislation and identify if a more formal structure is needed. In depth analysis of statistical data will be carried out in order to assess the extent of the housing problem in order to consider the regeneration concept as a possible solution.

The aim of this research, coupled with the type of information that will be collected presented itself as a primarily quantitative study, utilising a large number of facts and figures and analysing statistical data. This contrasts with a predominantly qualitative study that would have focused mainly on people’s opinions and perceptions (Bell, 2014). In depth analysis of statistical data will be carried out in order to assess the extent of the housing problem in order to consider the regeneration concept as a possible solution. account the writer’s approach was to employ a hybrid of both qualitative and quantitative.

If both are used the writer should be able to gain a wider spectrum and more detailed amount of research. The main quantitative research carried out will provide the writer with hard facts and data regarding the topic which will be enriched with the use of the qualitative research findings (Naoum 2012) of gaining the views and perceptions of people affected by the issues.

Data

Two main methods of data collection were used in gathering information for the purpose of this investigation. Firstly, primary data was collected in the form of semi-structured, open-ended questionnaires that were sent, via email, to each of the thirty-two local authorities in Scotland. housing associations and other organisations involved in affordable housing initiatives, e.g. Shelter. The reason for semi-structured questionnaires was so that results will not be constrained but also the results are not increasingly difficult to analyse, even if this method was slightly more time consuming.

Secondary data was collected from a number of sources such as books, journals, published statistics, websites and newspapers. One obvious advantage of collecting secondary data was that not a lot of time was spent collecting the data but instead time was used analysing it and coming to conclusions. Secondary data play a key part in coming to conclusions in this investigation as factual and statistical evidence can be used to either back up or contradict the data collected from questionnaires. For example, the Government or housing association may not be willing to admit that they have initiatives that are not functioning efficiently; however figures gathered could help to prove otherwise.

3.4 Questionnaire Design

As part of the research a structured questionnaire was sent to Scotland’s 32 local authorities made up of a series of questions covering a range of empty property issues, and requested both factual and attitudinal responses. It was designed to establish the main reasons behind the problem, what tools are available to, and if more could be done by councils in the regeneration of empty dwellings.

The questionnaire utilises a mix of ‘closed’questions, limited to a yes/no answer, ‘open’ questions, where the recipient is requested to provide an opinion or expand on the issue the question addresses and ‘Quantity’ questions where a numerical response is requested. Certain questions request the recipient give a ‘ranked’ response in order of the most common situation where there is expected to be more than one answer, and a several questions invite the recipient to give further information or opinions if desired.

The research questions were tested against the following standards as they were composed:

- Is the question relevant to survey objectives?

- Is the question clear and concise?

- Is the question leading or biased?

- Could the question be sensitive for any member of the population?

- Will the data recovered be in a format that will lend itself to analysis?

(Frazer, L & Lawley, M 2000)

The expected data produced will be mainly quantitative numerical information but will also yield integral qualitative observations and narrative data.

Additional Telephone Interview

Additional telephone interviews were carried out to gain a better understanding of the problem with CPO. For these short interviews 6 councils with a dedicated empty homes officer were contacted and as such phonesuited a personal

3.5 Ethical Considerations

This dissertation does not specifically involve a particularly sensitive subject however, the method of data collection utilized involved requesting participants to fill in a questionnaire asking for their professional opinions as well as personal views for analysis. The following principles stated by Bryman and Bell, 2007 as the ten most important ethical considerations in dissertations were therefore considered and followed during the research project –

- Research participants should not be subjected to harm in any ways whatsoever.

- Respect for the dignity of research participants should be prioritised.

- Full consent should be obtained from the participants prior to the study.

- The protection of the privacy of research participants has to be ensured.

- Adequate level of confidentiality of the research data should be ensured.

- Anonymity of individuals and organisations participating in the research has to be ensured.

- Any deception or exaggeration about the aims and objectives of the research must be avoided.

- Affiliations in any forms, sources of funding, as well as any possible conflicts of interests have to be declared.

- Any type of communication in relation to the research should be done with honesty and transparency.

- Any type of misleading information, as well as representation of primary data findings in a biased way must be avoided. (Bryman and Bell, 2007)

With any survey, there is a degree of risk that questions may be hurriedly answered or answered in a less than truthful manner. For this reason, it was decided to offer anonymity to those requiring it.

3.6 Research Restrictions

Regarding restrictions faced by the author during the research, the following factors were apparent:

- As personal interviews were the chosen approach, this limited the data collection as it was only taken from professionals in the central belt of Scotland. This eliminated the chance to gather data from other areas within Britain, or further still, overseas.

- As qualitative research and data collection methods were adopted, there was no statistical analysis in regards to project cost or time, for example, which numerical data and quantitative analysis would have portrayed, thus basing the researcher’s information solely on opinion rather than fact.

3.7 Chapter Summary

After carrying out research into the different methods of approaching data collection and subsequent analysis, the researcher obtained a thorough knowledge and understanding of the various techniques available. Through analysing the chosen subject and the data available, a mix of qualitative and quantitave approach was used with personal interviews being the main method of data collection to allow for descriptive responses around prefabrication and to gather personal opinion on the subject in relation to different projects. Ethical considerations and research limitations were also stated.

Chapter 4 Survey Results and Analysis

4.1 Main Survey

The questionnaire was sent out to every Local Authority in Scotland giving a potential maximum return of thirty-two. The questionnaire received twenty-three replies, achieving an overall response rate of a 72%. After several emails and follow up phone calls it was accepted that a proportion of the councils contacted would not reply. This figure compares with similar surveys such as the Scottish Empty Homes Partnership Annual Report 2017 and the Review of the Homelessness (Scotland) Act 2003 conducted by Shelter Scotland in 2016 that managed to gain a response of 77% and 50% respectively.

Questionnaire results

Question 1 – Which Local Authority are you employed within?

The first question simply asked the respondent to state which Local Authority they represented.

90.9% of this Local Authorities that responded indicated that a specific Scottish empty homes enforcement tool would be ‘very useful’ (63.6%) or ‘useful’ (27.3%). We also asked councils what type of enforcement tool they would find useful, and received the following ideas:

Summary of Survey Findings

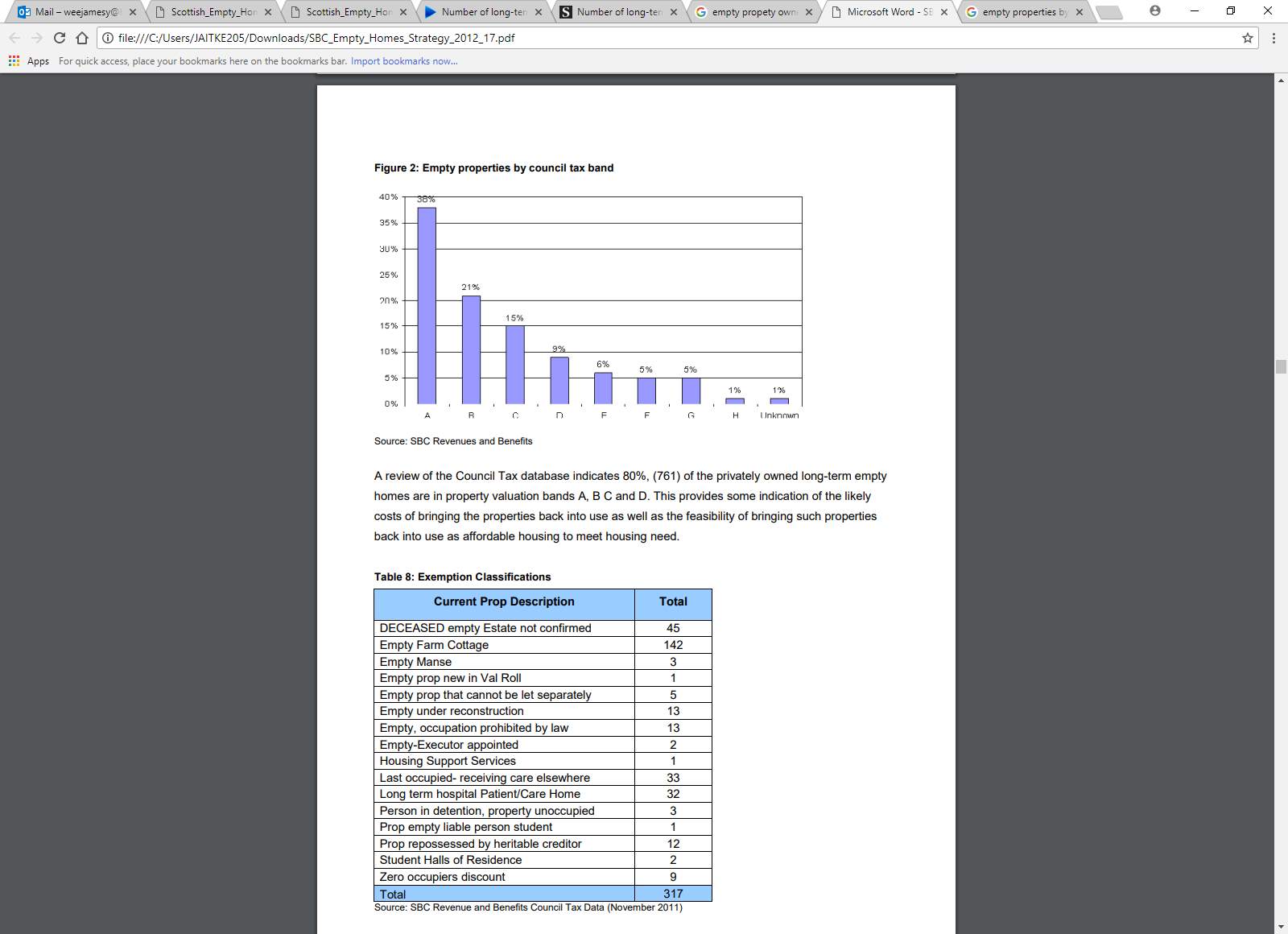

Half of empty properties are found within the central area of the Scottish Borders, unsurprising given it is the most densely populated area

55% are houses and a further 24% are flats

Almost half of respondents said the standard of the property was ‘poor’ or ‘very poor

Question 1 – Which LA are you employed within ?

Question 2 – Is there an Empty Homes Officer employed within this Local Authority?

19 of the 23 councils that responded stated that there was an Empty Homes Officer employed

Question 3 – Does your Local Authority have an Empty Homes Strategy?

To your best knowledge, how many private homes in your LA have been empty for?

More than 1 year –

Chapter 5

In addition, some local authorities offer financial assistance for bringing an empty home back into use through either grants or loans. Conditions are often attached, for example, that the property must be let to a household nominated by the council.

Discuss with mortgage lenders

+

Housing Re-Use Power Proposal

This research has uncovered the necessity for a new tool for Councils to take action on behalf of neighbours and the wider community on property which is empty and causing problems and where other action to address it has not been successful. In England and Wales the two existing tools – enforced sale and EDMOs – have quite different origins and have evolved quite separately. In the writers view, the starting point for discussion should be a single unified approach with the decision as to sale or renting regarded as a form of action towards the end of the process. So an overview of the process might be:

A long term empty property is manifestly causing problems in a neighbourhood.

The local authority seeks to engage with the owner, offering advice and assistance; possible access to funding to bring it up to standard if needed; and access to other parties who might help with its re-use.

If all of these approaches fail to resolve the problem, the local authority seeks to use the powers outlined here, by first making a declaration that the property is long term empty and that the best way to address problems it is causing is to secure its re-use.

The owner then is given a final specified period to bring the property into use

If and when that period elapses, the council then has the power to apply an order to secure the property for re-use, either for letting or for sale.

The property is brought up to a specified standard as part of the process – for example, the repairing standard and in a way which addresses the detriment.

The sale price and the level and length of letting allows the Council to cover its costs of taking action and any ongoing management costs, with the remaining receipts or rental income going to the owner.

At the point of the council declaring the property to be long term empty and at the point of securing its re-use the owner can apply to the court or another form of tribunal to challenge that process.

Chapter 6 – References

Anon, (2017). Available at: https://www.gha.org.uk/about-us/media/blogs/is-housing-first-the-silver-bullet-to-end-homelessness [Accessed 6 Dec. 2017].

Bell, J. (2014). Doing Your Research Project. Milton Keynes: McGraw-Hill Education.

Creswell, J W. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd.

Direct.gov.uk. (2016). Council action on empty properties. [online] Available at: http://www.direct.gov.uk/article/7387/Council-action-on-empty-properties [Accessed 29 Nov. 2017].

Ipsos MORI (2006) Survey of Empty Properties July 2006, Ipsos MORI

Frazer, L & Lawley, M (2000) Questionnaire Design & Administration. John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd.

Glasgow City Council. (2017). Glasgow’s Housing Strategy 2017-2022. Glasgow: Glasgow City Council, 2017. Web 6 May 2017

Glasgow City Council, 2017. Telephone conversation regarding empty property figures. Personal communication, 05 May 2017.

Glasgow Housing Association, 2017. Telephone conversation regarding waiting list figures. Personal communication, 06 May 2017.

Naoum, S. (2012). Dissertation research and writing for construction students. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

North Lanarkshire Council (2016) Empty Homes Statement for the Development of the Local Housing Strategy 2016-2021. (2016). Glasgow: North Lanarkshire Council.

Nurton, J (2009) ‘The house next door is a derelict eyesore – what can we do?’ The Independent, London 7th Jan 2009.

Scottish Government (2017). Housing Statistics for Scotland – Housing lists. Public Document 2017

Scottish Government. (2017). Housing Statistics for Scotland – New House Building. Public Document 2017. Web 4 May 2017

Scottish Housing News. (2017). New research reveals Scottish public’s concerns regarding empty homes – Scottish Housing News. [online] Available at: http://www.scottishhousingnews.com/10407/new-research-reveals-scottish-publics-concerns-regarding-empty-homes/ [Accessed 23 Nov. 2017].

Shelter Scotland (2016). Scottish Empty Homes Partnership Annual Report 2015-16. 2016. Web, 5 May 2017.

Scotland.shelter.org.uk. (2017). Scottish Empty Homes Partnership. [online] Available at: https://scotland.shelter.org.uk/empty_homes/scottish_empty_homes_partnership [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

Shelter Scotland (2016). Empty property case studies and current projects. 2016. Web, 5 May 2017.

Walliman, N. (2011). Your Research Project. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

https://stv.tv/news/politics/1404292-number-of-long-term-empty-homes-rises-to-more-than-37-000/

http://www.johnpullen.co.uk/uploads/1/9/3/0/19305517/explanatory_memorandum_to_si_367.pdf

Scottish Borders Council Empty Homes Strategy 2012 – 2017

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Property"

Property refers to buildings and structures, owned by an individual, group of people, or an organisation. There are three types of property, including public property, private property, and collective property.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: