Importance of Safety Netting Patients

Info: 11548 words (46 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Healthcare

I declare the use of pseudonym/s within this assignment in respect of individuals and/or healthcare services. This declaration recognises the need to uphold anonymity and confidentiality where evidence related to my professional practice in healthcare is shared / disseminated.

Presenting Complaint: – Left sided flank pain

HxPC: – 81 year old female complaining of left sided flank pain for the past 2 days. She was seen by her GP yesterday who queried diverticulitis, the GP advised regular pain relief, to be taken. The manager of the nursing home phoned 111 for advice, in regards to this patient, as she was unhappy with the patient’s progress. A 999 response was indicated by 111 and an emergency RRV was sent.

PMHx: – Pt has arthritis and Alzheimer’s disease

DHx: – Donepezi, paracetamol and codeine

SHx: – Resides in a nursing home

Allergies: – No known drug allergies

Examination:

RS: – Good colour. No shortness of breath. Talking in full sentences. No recent colds or chest infection. Chest clear on auscultation, bilateral air entry, no wheeze. SpO2 96%. Respiratory rate 18b/min

CVS: – No central chest pain. No pedal oedema. No Hx of cardiac conditions. Regular radial pulse at 92b/min. Blood pressure 145/85. 12 lead ECG Normal sinus rhythm. Capillary Refill < 2 seconds

CNS: – GCS 15. No headache. No dizziness. FAST Negative. Alert. Orientated to time of day, location and current situation. No neurological deficit. Blood Glucose: 7.3mmol/L. Tympanic temperature 37.2°C.

Abdo: Soft. No boarding. Guarding on palpitation to left flank. Strong smell of urine. No incontinence. Urine sample tested, turbidity is dark and offensive. Urinalysis, positive for nitrates and leucocytes, Indicates UTI

MSK: – Full range of movement in all limbs. Able to mobilise well, witnessed by staff and crew. No evidence of trauma in left flank area.

DD: – Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

?? Pyelonephritis

IMP: – UTI

Action Plan

- Adopt standard precautions.

- Gain consent, introduce self and crew and reassure.

- Gain patient and current complaint history.

- Conduct physical examination.

- Obtain urine sample and test, positive for UTI.

- Contact patients GP, inform GP of findings, GP happy for patient to be treated with Trimethoprim for a UTI after considering co-amoxiclav.

- GP to visit in the afternoon and take bloods.

- Inform staff to encourage the patient to take fluids and pain relief as prescribed.

- Trimethoprim supplied under PGD. One tablet to be taken twice a day for three days.

- Inform patient and carers of possible side effects.

- Worsening advice – 999 call back if required.

This case study focuses on the importance of safety netting patients that are not conveyed to a definitive place of care by pre-hospital clinicians. Emergency admissions and attendances to Emergency Departments (ED) have increased every year, over the past twelve years, in England. (Blunt, Bardsley and Dixon, 2010; Appleby, 2013; The King’s Fund, 2013; Parliament. House of Commons, 2017)

After assessing a patient, there may me the option of treating the patient out of hospital, therefore, preventing a hospital admission. If the patient requires further treatment or assessment, it is important to give the patient appropriate advice, in regards to ongoing care or any complications that may occur. This needs to include who to contact and how to contact them if the condition worsens (de Vos-Kerkhof et al., 2015)

Using safety netting as a consultation technique ensures a timely reassessment of a patient (Almond, Mant and Thompson, 2009). The consultation model by Neighbour (1987) is a popular model. It consists of a five point checklist; connecting, summarising, handing over, safety netting and housekeeping. This consultation model is easy to use and follow, this is aided by its natural flow. It is concise and promotes partnership by being patient centred. This model was originally developed for use by General Practitioners (GP), however it can be easily used by paramedics as it aims for the clinician to work within their knowledge base, freeing them from using their intuitive input (Evans et al., 2013). When safety netting a patient to leave them at home, paramedics should remember the three C’s, as shown in appendix one (Silverton, 2014). By following these processes, clinicians can question the appropriateness of the safety netting.

When it is decided that a patient can be managed in the community safely and therefore does not require admission to an ED, but does require further care, safety netting and arrangement of an alternative pathway must be carried out (South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust, 2014). Alternatives to ED admission are varied, including, but not limited to, GP, Minor Injury Units, self care, Pharmacist, District nurses (Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, 2015) .

Overcrowding within ED is at crisis point and currently at the centre of national attention (Smith and Wilkinson 2017), it is important for the ambulance service to make appropriate referrals for patients. To meet the demands of the changing National Health Service (NHS), it is necessary to ensure patients are referred to the most appropriate services for their condition. According to the Commissioning for Quality and innovations (NHS England, 2015), there is an ‘increase in the number of patients with urgent and emergency care needs who are managed close to home, rather than in a hospital (A&E or inpatient) setting’. This report highlights that there is a government agenda, where, when appropriate, patients are left at home ensuring they get the right care at the right time in the right place (South, 2012).

In conclusion, patients need to be aware of why they are not being conveyed to ED and how they are being safety netted. They need to understand what they need to if their condition worsens or fails to improve. Finally patients need to understand how to seek further help if required. More research into safety netting is required to identify how to improve this process for the safety of patients.

References

Almond, S., Mant, D. And Thompson, M. (2009) ‘Diagnostic Safety-netting’, The British Journal of General Practice. 59(568), pp 872-874. Doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X472971

Appleby, J. (2013) ‘Are Accident and Emergency Attendances Increasing?’, British Medical Journal, 346, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3677

Blunt, I., Bardsley, M. and Dixon, J. (2010) Trends in Emergency Medicine in England 2004 – 2009. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/trends-emergency-admissions-report-web-final.pdf. (Accessed: 13 March 2017)

de Vos-Kerkhof, E., Geurts, D. H. F., Wiggers, M., Moll, H. A. And Ostenbrink, R. (2015) “Tools for ‘Safety Netting’ in Common Paediatric Illnesses: A Systematic Review in Emergency Care”, Archives of Disease in Childhood. 101(2), pp. 129-131. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306953

Evans, R., McGovern, R., Birch, J. and Newbury-Birch, D. (2013) ‘Which Extending Paramedic Skills are Making an Impact in Emergency Care and can be Related to the UK Paramedic Systems, A Systematic Review of the Literature’. Emergency Medicine Journal, 31, pp. 594-603. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-202129

Neighbour, R. (1987) The Inner Consultation. How to Develop an Effective and Intuitive Consulting Style. Lancaster: Kluwer Academic Publisher

NHS England (2015) Commissioning for Quality and Innovation. Guidance for 2017/19. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/cquin-2017-19-guidance.pdf (Accessed: 13 March 2017)

Parliament. House of Commons. (2017) Accident and Emergency Statistics: Demand, Performance and Pressure (6964). London: The Stationery Office.

Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust (2016) Do you need to come to A&E? Available at: https://www.royalfree.nhs.uk/services/services-a-z/emergency-department/do-you-need-to-come-to-ae/ (Accessed 13 March 2017)

Silverton, P. (2014) ‘Reducing Risk/Improving Safety: Safe Management Plans’, Ambulance UK. 29(4). pp. 178-179

Smith, M. and Wilkinson, R. (2017) ‘One in six A&E wards under threat amid overcrowding crisis’, The Mirror, 6 February 2017. Available at: http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/one-six-ae-wards-under-9765930 (Accessed: 13 March 2017)

South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (2014) Appropriate Care Pathway Policy. Available at: http://www.swast.nhs.uk/Downloads/SWASFT%20Bulletin/Bulletin%20links/Appropriate%20Care%20Pathway%20Policy.pdf (Accessed: 13 March 2017)

South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (2016) Right Care, Right Place, Right Time. Available at: http://www.swast.nhs.uk/right_care.htm (Accessed: 13 March 2017)

The King’s Fund (2013) Urgent and Emergency Care: A Review for NHS South of England. Available at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/Journals/2013/05/02/z/d/s/Kings-Fund-report-urgent-and-emergency-care.pdf (Accessed: 13 March 2017)

Appendix One

The three C’s in safety netting

| Capacity | Assess the person’s mental capacity and mental competence

to follow the safety-netting instructions that you are providing. |

| Compliance | Assess the person’s ability to comply with instructions, in

terms of the equipment that they have available; their knowledge base and any psycho-social or logistical factors that may influence their ability to comply with your instructions. |

| Comprehension | Assess the person’s comprehension of the information

that you have imparted, both in terms of the clinical re-assessment that you are asking them to perform; the decisions that you are asking them to make; and the actions that you are asking them to take in response to their findings. |

Silverton, P. (2014)

Student Number: 10480521

Programme Title: BSc (Hons) Paramedic Practitioner

Module Code: PARA301

Module title: Refining Practitioner Skills for Patient Care

Faculty of Health and Human Sciences

School of Health Professions

Submission deadline date: 08 May 2017

Word Count: 545

I 10480521 declare the use of pseudonym/s within this assignment in respect of individuals and/or healthcare services. This declaration recognises the need to uphold anonymity and confidentiality where evidence related to my professional practice in healthcare is shared / disseminated

Presenting Complaint: – Shortness of Breath (SOB)

HxPC: – 61 year old Male claims to have been short of breath for the past 1/52, with a productive cough, green phlegm. He has been unable to get a GP appointment for another 2 weeks. He phoned 111 for advice, an emergency 999 response was sent.

PMHx: – COPD, Left Leg Amputation, Diabetes

DHx: – Paracetamol, Salbutamol inhaler, Tiotropium, Metformin

SHx: – Lives at home with partner, Carers visit twice daily

Allergies: – No known drug allergies

Examination:

RS: – Good colour. No shortness of breath. Talking in full sentences. No recent colds or chest infection. Chest clear on auscultation, bilateral air entry, end expiratory wheeze. No intercostal recession, no use of accessory muscles. No flared nostriles. Non-smoker. No home O2. SpO2 94%. Respiratory rate 18b/min. Initial peak flow 350l/min final peak flow 500l/min.

CVS: – No central chest pain. No pedal oedema. No Hx of cardiac conditions. Regular radial pulse at 86b/min. Blood pressure 130/75. 12 lead ECG Normal sinus rhythm. Capillary Refill < 2 seconds

CNS: – GCS 15. No headache. No dizziness. FAST Negative. Alert. Orientated to time of day, location and current situation. No neurological deficit. Blood Glucose: 8.4mmol/L. Tympanic temperature 36.9°C.

Abdo: Soft. No boarding or guarding, urine frequency and bowel movements all normal for patient

MSK: – Full range of movement in all limbs. Able to mobilise well, witnessed by staff and crew. Pt has prosthetic left leg

DD: – Chest Infection

??Pulmonary Embolism

IMP: – Chest Infection

Action Plan

1. Adopt standard precautions.

2. Gain consent, introduce self and crew and reassure.

3. Gain patient and current complaint history.

4. Conduct physical examination.

5. Nebulise with 5mg salbutamol with 6l/min O2. Peak flow above 75% of reported best

6. Advice patient on ‘Rescue Pack’ from GP

7. Drugs administered/supplied:

a. Salbutamol Inhaler 100mcg PRN

b. Prednisolone 5mg x 6 OD

c. Clarithromycin 500mg BD

8. Advice patient to complete course of antibiotics

9. Worsening advice given

10. Inform patient GP and arrange GP visit

This case study focuses on the importance of accurate history taking and using that history to come to a diagnosis whilst considering differential diagnosis, within the pre-hospital environment. Differential diagnosis refers to the consideration of different conditions that share similar symptoms, the clinician then decides on which condition is most likely. (Stiggelbout, Vries and Scherer, 2015). This systematic review safeguards clinicians, helping to prevent target fixation, reducing the chances of them missing other important observations.

The 111 service is used by patients to obtain medical advice, this service is used more than any other National Health Service (NHS) pathway (NHS England, 2015). Patients want to know the cause of their illness and how it can be treated efficiently. The paramedic’s role is to find a route cause for the patient’s condition, and rule out anything life threatening, treating the patient. If they can’t find a cause they are to treat the symptoms.

Accurate history taking enables the clinician to understand the events leading to the patients call. A good history taking and examination technique are more important than advances in treatment (Douglas, Nicol and Roberson, 2005). Introducing staff, and gaining informed consent must always be the first thing that happens with patient contact (Mental Capacity Act, 2005), this is also a professional obligation (Health and Care Professions Council, 2014). If the primary assessment does not highlight any time critical conditions, a secondary assessment is carried out.

History of presenting complaint is the most detailed part of an assessment. This is achieved through good questioning, good communication and vital sign observations. Gregory and Mursell (2010) break down the history into the categories shown in appendix one. Previous medical history and current medications are also important factors (Blaber and Harris, 2011; Gregory and Ward, 2010). Before considering any drug interventions, it is important to document any allergies as well as family history (Hughes, 2008). This will highlight any potential genetic predispositions to certain conditions (Bickley, 2013).

For some patients, social history holds a higher importance (Jenkins, 2013). This builds a picture of the patient’s illness or injury and helps the clinician to understand how it is affecting the patient’s life. A patient with a chest infection, who is well and young may be able to cope at home alone, where as an elderly patient with comorbidities, may struggle at home alone.

A full system review of a patient can uncover other symptoms the patient was unaware of, thus protecting the clinician from missing something. Questions ordered by bodily system should prompt the clinician to areas which need a thorough assessment (University of California, 2015). Appendix two shows an example of this.

It is a professional obligation for paramedics to form a differential diagnosis. The Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) Standards of Proficiency for Paramedics states ‘Paramedics must be able to conduct a thorough and detailed physical examination of the patient using appropriate skills to inform clinical reasoning and guide the formulation of a differential diagnosis across all age ranges’,

By carrying out a thorough assessment, a clinician, by treating a patient on scene, can prevent unnecessary ED admissions. This means the patient can stay at home, reducing the workload within ED and reducing the spread of infection (National Audit Office, 2009)

With government drivers such as Taking Healthcare to the Patient 2 (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2011), NHS Business Plan (NHS England, 2016) and Transforming the NHS Ambulance Services (Department of Health, 2011), treating patients at home meets these.

References

Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (2011) Taking Healthcare to the Patient 2: A Review of 6 years; progress and Recommendations for the Future. Available at: http://aace.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2015/05/taking_healthcare_to_the_patient_2-Pdf (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

Bickley, L. S. (2013) Bates’ Pocket Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 7th edn. London: Lippincott Mlliams and Nllkins

Blaber, A. and Harris, G. (2011) Assessment Skills for Paramedics. Maidenhead: McGiaw-Hill.

Department of Health (2011) Transforming NHS Ambulance Services. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2011/06/n10121086.pdf (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

Douglas, G,. Nicol, F. and Roberson, C (2005) Macloed’s Clinical Examination. London, Elsevier.

Gregory, P. and Mursell, l. (2010) Manual of Clinical Paramedic Procedures.

Chichester: VWey-Blackwell.

Gregory, P. and Ward, A. (2010) Sanders Paramedic Textbook. Burlington MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Health and Care Professions Council (2014) Standards of Proficiency: Paramedics. Available at: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/1000051CStandards_of_Proficiency_Paramedics.pdf (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

Hughes, R., G. (2008) Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Jenkins, S(2013) “History Taking, Assessment and Documentation for Paramedics”, Journal of Paramedic Practice, 5(6), pp. 310-316.

Mental Capacity Act 2005, c. 9. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/introduction (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

National Audit Office (2009) Reducing Healthcare Associated Infections in Hospitals in England. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wpcontent/upIoads/2009/06/0809560.pdf (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

NHS England (2015) NHS 111 opens new front door to improved urgent care. Available at: https:I/www.england.nhs.uk/2015/10/nhs1 1 1-urgent-care (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

NHS England (2016) Our 2016/17 Business Plan. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-contentluploads/2016/03/bus-plan-16.pdf (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

Stiggelbout, A. M., de Vries, M. and Scherer, L. (2015) Medical Decision Making, in The VWey Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK.

University of California (2015) A Practical Guide to Clinical Medicine. Available at: https://meded.ucsd.edu/clinicalmed/ros.htm (Accessed: 15 March 2017)

Appendix One

Gregory, P. and Mursell, I. (2010)

History of presenting complaint

| Categories within of history of presenting complaint |

| ►Location of the symptom |

| ► Duration of symptoms |

| ►Onset of symptoms |

| ► Aggravating and Alleviating factors 0 Any attributable causes |

| ► Previous episodes |

| ► Severity of symptoms |

| ► Nature of the symptoms |

| ► Any medications used to relieve the symptoms |

Appendix two

Gregory, P. and Ward, A. (2010)

Review of Systems

| System | Considerations |

| General | Appearance, Orientation and communication ability. |

| Respiratory | Cough, Haemoptysis, Chest Pain, Breathlessness. |

| Cardiovascular and Circulatory | Chest pain, Palpitations, intermittent claudication, Ankle oedema, Orthopnoea, Dyspnoea. |

| Nervous System | Headaches, Dizziness, Disturbance of vision, taste, smell, hearing or speech, Faints, fits or loss of consciousness, falls. |

| Musculoskeletal System | Altered mobility, Muscle weakness or loss of power or function, Joint pain or swelling or stiffness, Muscle pain |

| Gastrointestinal System | Changes in appetite or thirst, vomit or nausea, bowels, diarrhoea, constipation, changes in frequency, bowel habit, rectal bleeding or melaena, jaundice, dysphagia, weight loss/gain, abdominal pain. |

| Genitourinary System | Disuria, haematuria, frequency, incontinence, pain or discomfort, colour and smell. |

Student Number: 10480521

Programme Title: BSc (Hons) Paramedic Practitioner

Module Code: PARA301

Module title: Refining Practitioner Skills for Patient Care

Faculty of Health and Human Sciences

School of Health Professions

Submission deadline date: 08 May 2017

Word Count: 506

I 10480521 declare the use of pseudonym/s within this assignment in respect of individuals and/or healthcare services. This declaration recognises the need to uphold anonymity and confidentiality where evidence related to my professional practice in healthcare is shared / disseminated

Presenting Complaint: – Dizziness

HxPC: – 57 year old Male, past 2/7 been having dizzy spells upon standing. He has recently been diagnosed with hypertension. His GP prescribed Ramipril 1/52 ago He phoned 111 for advice, an emergency 999 resource was dispatched.

PMHx: – Hypertension

DHx: – Ramipril

SHx: – Lives at home with his wife

Allergies: – No known drug allergies

Examination:

RS: – Good colour. No shortness of breath. Talking in full sentences. No recent colds or chest infection. Chest clear on auscultation, bilateral air entry, no wheeze. SpO2 94%. Respiratory rate 16b/min.

CVS: – No central chest pain. No oedema. No Hx of cardiac conditions. Regular radial pulse at 74b/min. Blood pressure 100/70 sitting 90/70 standing. 12 lead ECG

Normal sinus rhythm. Capillary Refill < 2 seconds, Normal heart sounds.

CNS: – GCS 15. No headache. Constant dizziness. FAST Negative. Alert. Orientated to time of day, location and current situation. No neurological deficit. Blood Glucose: 4.8mmol/L. Tympanic temperature 37.3°C.

Abdo: Soft. No boarding or guarding, urine frequency and bowel movements all normal for patient

MSK: – Full range of movement in all limbs. Unsteady on his feet

DD: – Hypotension

? Vasovagal

?? Presyncope

IMP: – ?Hypotension due to new medication

Action Plan

1. Adopt standard precautions.

2. Gain consent, introduce self and crew and reassure.

3. Gain patient and current complaint history.

4. Conduct physical examination Including a sitting and standing BP.

5. Explain to patient the findings and what the probable cause of his dizziness is.

6. Inform patient that it is advisable for him to go to hospital.

7. Patient taken out to ambulance on carry chair

8. Convey the patient to the nearest ED

9. Hand over patient to ED Nurse

This case study focuses on the importance of concise patient handovers to other health care professionals and the challenges that may arise. It is a professional responsibility for health care professionals to handover patients and is an essential part of practice (Evans et al., 2010). A clinical handover is a process wherein the professional responsibility for the patient or patients is passed on to another person or professional group, this can be for all or some aspects of the patients care (The National Patient Safety Agency, 2004). The Royal College of Surgeons (2007) highlighted that there is an increase in patient handovers and that there is a need for clinicians to provide quality handovers, also recommending improving handovers and regulating them.

There are many ways paramedics can hand over a patient, by using radio, telephone, verbal and written e.g. Patient Clinical Records and electronic Patient Clinical Records. Paramedics may hand over patients to many other clinicians, including Emergency Department (ED) doctors and nurses, General Practitioners, carers etc. (Wood et al., 2014)

‘Zero Tolerance – Making ambulance handover delays a thing of the past’ (NHS Confederation, 2012), focuses on reducing handover times within the National Health Service (NHS). It is expected to take 15 minutes to hand over a patient between an ambulance crew and the receiving hospitals ED (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012). The National Audit Office report that around 500,000 hours were lost during 2015-16 due to handovers in ED taking longer than 30 minutes, this is putting pressure on ambulance services and their staff (National Audit Office, 2017). There have been year on year increases in hand over delays since 2011 (Monitor, 2015). These delays can have a knock on effect, increasing delays.

Challenges that can limit handover effectiveness may be a lack of structure, getting the attention of the clinician receiving the handover, noise, duration or recalling information about a complex patient (Thakore and Morrison, 2001). Handovers can be complex with other professions involved requiring different information regarding the patient (Royal College of Surgeons, 2007).

The patient care should focus on the needs and wants of the patient, without effective handovers, the continuity of care can fail resulting in the patient not getting the care they require (Loseby, Hudson and Lyon, 2013). Poor communication and human factors can result in a failed handover which may cause the patient harm (Royal College of Physicians, 2015).

Improvements have been made by ambulance staff, however, hospitals need to make improvements in how handovers are received and every hospital has a different way of accepting a patient. Conflict, hierarchical differences, interpersonal power and concerns with upward influence have a bearing on how a handover is received (Sutcliffe, Lewton and Rosenthal, 2004).

Research highlights that handovers need to be understood as a sociotechnical activity that is part of an organisations practice. National targets, capacity and patient flow are intricately linked to the quality of the handover. To improve, focus should be aimed at providing clinicians with the flexibility to resolve tensions within handovers by making trade-offs (Sujan et al., 2014)

References

Evans. S. M., Murray. A., Patrick. I., Fitzgerald. M., Smith. S. and Cameron. P. (2010) ‘Clinical Handover in the Trauma Setting: a Qualitative Study of Paramedics and Trauma Team Members’, Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19(6), pp. 1-6. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.039073.

Health and Social Care Information Centre (2012) Ambulance Services England 2011-2012. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB06869/ambu-serv-eng-2011-2012-rep.pdf (Accessed: 19 March 2017).

Loseby. J., Hudson. A. and Lyon. R. (2013) ‘Clinical Handover of the Trauma and Medical Patient: a Structured Approach’, Journal of Paramedic Practice, 5(10), pp. 563-567.

Monitor (2015) A&E Delays: Why Did Patients Wait Longer Last Winter? Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/458764/AE_delay_main_report_final.pdf (Accessed: 19 March 2017).

National Audit Office (2017) NHS Ambulance Services. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/NHS-Ambulance-Services.pdf (Accessed: 19 March 2017)

National Patient Safety Agency (2004) Seven Steps to Patient Safety: Full Reference Guide. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/collections/seven-steps-to-patient-safety/?entryid45=59787 (Accessed: 19 March 2017).

NHS Confederation (2012) Zero Tolerance – making ambulance handover delays a thing of the past. Available at: http://aace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Zero_tolerance061212.pdf (Accessed: 19 March 2017).

Royal College of Physicians (2015) Acute Care Toolkit 1: Handover. Available at: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/acute-care-toolkit-1-handover (Accessed: 19 March 2017)

Royal College of Surgeons (2007) Handover: Guidance from the Working Time Directive Working. Available at: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/publication.2007-05-14.3777986999/ (Accessed: 19 March 2017).

Sujan. M., Spurgeon, P., Inada-Kim, M., Rudd. M., Fitton, L., Horniblow, S., Cross, S., Chessum, P. and Cooke. M. W. (2014) ‘Clinical Handover Within the Emergency Care Pathway and the Potential Risks of Clinical Handover Failure (ECHO): Primary Research’, Health Services and Delivery Research, 2(5), pp. 1-170. doi: 10.3310/hsdr02050.

Sutcliffe. K. M., Lewton. E. and Rosenthal. M. M. (2004) ‘Communication Failures: An Insidious Contributor to Medical Mishaps’, Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 79(2), pp. 186-194.

Thakore. S. and Morrison. W. (2001) ‘A Survey of the Perceived Quality of Patient Handover by Ambulance Staff in the Resuscitaion Room’, Emergency Medical Journal, 18(4), pp. 293-296. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.4.293.

Wood, K., Crouch, R., Rowland, E., & Pope, C. (2014). ‘Clinical handovers between pre-hospital and hospital staff: Literature review’, Emergency Medicine Journal, 32. Pp. 557-581. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-203165.

Student Number: 10480521

Programme Title: BSc (Hons) Paramedic Practitioner

Module Code: PARA301

Module title: Refining Practitioner Skills for Patient Care

Faculty of Health and Human Sciences

School of Health Professions

Submission deadline date: 08 May 2017

Word Count: 508

I 10480521 declare the use of pseudonym/s within this assignment in respect of individuals and/or healthcare services. This declaration recognises the need to uphold anonymity and confidentiality where evidence related to my professional practice in healthcare is shared / disseminated

Presenting Complaint: – Fall, Injured ankle

HxPC: – 54 year old female, Walking down the stairs in a garden centre after going to the toilet. She slipped off a stair and inverted her left ankle. On arrival she was siting on a chair in the restaurant with her leg elevated and cryotherapy taking place (freezer gel pack), She was shopping with her 20 year old daughter. Ankle pain was 7/10 with mild swelling

PMHx: – Normally fit and well

DHx: – None

SHx: – Lives at home with partner

Allergies: – No known drug allergies

Examination:

RS: – Good colour. No shortness of breath. Talking in full sentences. No recent colds or chest infection. Chest clear on auscultation, bilateral air entry, no wheeze. SpO2 99%. Respiratory rate 18b/min.

CVS: – No central chest pain. No oedema. No Hx of cardiac conditions. Regular radial pulse at 74b/min. Blood pressure 140/80 sitting Capillary Refill < 2 seconds, Normal heart sounds.

CNS: – GCS 15. No headache. No dizziness. FAST Negative. Alert. Orientated to time of day, location and current situation. No neurological deficit. Blood Glucose: 6.4mmol/L. Tympanic temperature 37°C.

Abdo: Soft. No boarding or guarding, urine frequency and bowel movements all normal for patient

MSK: – Full range of movement in all unaffected limbs. Unable to weight bare on left leg, No Pain in left knee, no swelling in left calf, no bony tenderness in tibia or fibula, no crepitus on movement. Pain in lateral malleolus, no pain on achilles tendon, no pain in 5th metatarsal, no pain in calcaneum. Pedal pulse present and marked.

DD: – Left ankle # Ottawa positive

? left ankle sprain

IMP: – Left ankle # Ottawa positive.

Action Plan

1. Adopt standard precautions.

2. Gain consent, introduce self and crew and reassure.

3. Gain patient and current complaint history.

4. Conduct physical examination and establish pain score.

5. Patient taken paracetamol 2 hours ago

6. Patient in 7/10 pain Entonox administered to good effect bringing pain to 1/10

7. Ankle immobilised using vacuum splint – re check pedal pulse

8. Patient taken out to ambulance on carry chair

9. Convey the patient to the nearest ED for x-ray and assessment

This case study focuses on diagnosing an ankle fracture or sprain, using the Ottawa ankle rules, shown in appendix one. Up to 1 in 5 sports injuries, which require an emergency response, are ankle injuries (Bahr and Maehlum, 2004). Mechanical falls are the most common cause for ankle injuries, 85% are caused by inverting the ankle (Lin, Hiller and Bie, 2010).

Every year between 1 and 1.5 million visits a year to Emergency Departments (ED) are due to ankle injuries (Boyce and Quigley, 2004). Making a diagnosis of a closed ankle fracture is often challenging out of hospital. The Ottawa rules by Stiell et al. (1994) are recommended for clinicians to use by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) (NICE, 2016), they are also suggested for managing minor injuries, as a way of deciding whether an x-ray is required (Willis and Dalrymple, 2015).

Accurately diagnosing a patients injury can help reduce the patents anxiety levels (Sman, Hiler and Refshauge, 2013), helping the clinician to direct the patient to the most appropriate care pathway (Swain et al., 2014). This ensures that patients get the right care at the right time (South, 2012), by achieving this the patients recovery time can be reduced and help the National Health Service trusts to meet their targets

Using a reflective model of history taking, asking what? Where? Why? When? And how? Is important during an assessment. This enables the clinician to carry out a full and accurate assessment of the patient, and highlights exactly how the injury occurred and events leading up to it (Ghaye, 2011).

The most common symptoms for ankle fractures are deformity, swelling, contusion, inflammatory response, instant and severe pain and the patient no longer has the ability to weight bare (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2013).

A sprain to the ankle occurs when the ligaments are damaged, this causes an inflammatory response, swelling and contusion. Sprains are classified in three grades as shown in appendix two (Wolfe, et al, 2001). The mnemonic PRICE is the treatment method recommended by NICE and is shown in appendix three (NICE, 2016). However immobility can have a negative effect on healing time and circulation (Medicine Information, 2016), this questioning the benefits of using PRICE

With bony tenderness in the lateral malleolar zone and she couldn’t weight bare for four steps after injury this made her Ottawa positive, this indicated a requirement for the patient to have an x-ray.

Using Ottawa ankle rules to rule out fractures has a high sensitivity, however, due to this it often gives a false positive. Patients who don’t meet requirements for x-ray are unlikely to have a fracture that is clinically significant. Utilising Ottawa ankle rules helps to reduce the number of x-rays and improves the flow of patients through ED

Diagnosing ankle injuries, either sprains or fractures, is complex and the injuries can result from varying types of trauma. Knowledge of the anatomy of the ankle and Ottawa ankle rules can help the clinician make an appropriate diagnosis and direct the patient to the right care.

References

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (2013) Ankle Fractures (Broken Ankle), Available at: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00391 (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (2015) Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care. 5th edn. Chicago: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Bahr, R. and Maehlum, S (2004) Clinical Guide to Sports Injuries: an Illustrated Guide to the Management of Injuries in Physical Activity. Leeds:Human Kinetics.

Boyce, S. H. and Quigley, M. A. (2004) ‘Review of Sports Injuries Presenting to an Accident and Emergency Department’, Emergency Medicine Journal, 21(6), pp. 704-706. doi: 10.1136/emj.2002.002873.

Ghaye, T. (2011) Teaching and Learning Through Reflective Practice: A Practical Guide for Positive Action, 2nd end. London: Routledge.

Hawkins. S. W. and Hawkins, J. R (2016) ‘Clinical Applications of Cryotherapy Among Sports Physical Therapists’, The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 11(1), pp. 141-148.

Health and Care Professions Council (2014) Standards of proficiency: Paramedics. Available at: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/1000051CStandards_of_Proficiency_paramedics.pdf (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

Hwang, C. (2003) Ottawa Ankle Rule. Available at: http://www.mdcalc.com/ottawa-ankle-rule/ (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

Jones. P., Dalziel, S. R., Lamdin. R., Miles-Chan. J. L. and Frampton. C. (2015) ‘Oral Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Versus Other Oral Analgesic Agents for Acute Soft Tissue Injury’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews’, 7, pp. 1-129. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007789.pub2.

Lin. C. W. C., Hiller. C.E. and Bie. R. A, (2010) ‘Evidence-Based Treatment for Ankle Injuries: A Clinical Perspective’, Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 18(1), pp. 22-28. doi: 10.1179/106698110X12595770849524.

Medicine Information (2016) Treating Sprains and Strains: Are You Doing It Wrong? Available at: http://www.aboutmedicine.tk/2016/05/treating-sprains-and-strains-are-you.html (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

National institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) Sprains and Strains. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2016) Sprains and Strains: When should I X-Ray?. Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!diagnosissub:1 (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

Sman. A.D., Hiler. C. E. and Refshauge. K.M. (2013) ‘Diagnosis Accuracy of Clinical Tests for Diagnosis of Ankle Syndesmosis injury: a Systematic Review’, British Association of Sport and Medicine, 47(10, pp. 20-628. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091702.

South. A. (2012) ‘Right Care, Right Place, Right Time?’, Journal of Paramedic Practice, 4(2), pp. 67

Stiell, I. G., McKnight. D. Greenberg. G. H. McDowell, I., Nair. N. C., Wells. G. A., Johns. C. and Worthington. J. R. (1994) ‘Implementation of the Ottawa Ankle Rules’, Journal of the American Medical Association, 271(11), pp. 827-832. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510350037034.

Swain. M.S., Henschke. N., Kamper. S. J., Downie. A.S., Koes. B.W. and Maher. C. G. (2014) ‘Accuracy of Clinical Tests in the Diagnosis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Systematic Review’, Chiropractic and Manual Therapies, 22(25), pp. 1-10. doi: 10.1186/s12998-014-0025-8.

Thompson. C., Kelsberg. G. and St Anna. L. (2003) ‘Heat or Ice for Acute Ankle Sprain?’, The Journal of Family Practice. 52(8).

Willis, S. and Dalrymple, R. (2015) Fundamentals of Paramedic Practice: A Systems Approach. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Wolfe, M. W., Uhl, T.L., Mattacola, C., G., and McCluskey ,L. C. (2001) Management of Ankle Sprains. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0101/p93.html#ref-list-1 (Accessed: 10 April 2017)

Appendix One

Ottawa ankle rules

(Stiell et al., 1994)

An ankle x-ray is only required if there is any pain in the malleolar zone and any of the following:

- Bone tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of lateral malleolus

Or

- Bone tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of medial malleolus

Or

- Inability to weight bare immediately and at the emergency department.

Appendix Two (Wolfe, et al, 2001)

Classification of Ankle Sprains

| I: partial tear of a ligament | Mild tenderness and swelling

Slight or no functional loss (i.e., patient is able to bear weight and ambulate with minimal pain) No mechanical instability (negative clinical stress examination) |

| II: incomplete tear of a ligament, with moderate functional impairment | Moderate pain and swelling

Mild to moderate ecchymosis Tenderness over involved structures Some loss of motion and function (i.e., patient has pain with weight-bearing and ambulation) Mild to moderate instability (mild unilateral positivity of clinical stress examination) |

| III: complete tear and loss of integrity of a ligament | Severe swelling (more than 4 cm about the fibula)

Severe ecchymosis Loss of function and motion (i.e., patient is unable to bear weight or ambulate) Mechanical instability (moderate to severe positivity of clinical stress examination) |

Appendix Three

PRICE mnemonic

(National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2016)

| Protection | Protect from further injury |

| Rest | Avoid activity for the first 48 – 72 hours. |

| Ice | For the first 48 – 72 hours, apply ice wrapped in a towel for 15-20 mins every 2-3 hours. |

| Compression | Compression or bandage to the injured area to limit swelling and movement that could damage it further. |

| Elevation | Keep the injured area raised to reduce swelling |

Student Number: 10480521

Programme Title: BSc (Hons) Paramedic Practitioner

Module Code: PARA301

Module title: Refining Practitioner Skills for Patient Care

Faculty of Health and Human Sciences

School of Health Professions

Submission deadline date: 08 May 2017

Word Count: 522

I 10480521 declare the use of pseudonym/s within this assignment in respect of individuals and/or healthcare services. This declaration recognises the need to uphold anonymity and confidentiality where evidence related to my professional practice in healthcare is shared / disseminated

Presenting Complaint: – Self harm

HxPC: – 19 year old female, Deliberatly cut left upper arm in the lateral medial location, this happened 20 mins before arrival, her friend saw her do it and called 999, Advanced Nurse Practitioner (ANP) Rapid Response Vehicle (RRV) responded within 15 minutes. Previous history of self harming from the age of 13. Patient has capacity.

PMHx: – Depression, Hx of self harm (Cutting), up to date with Tetanus.

DHx: – Citalopram 40mg – one at night

SHx: – Lives at home with friend – house is cold

Allergies: – Penicillin

Examination:

RS: – Good colour. No shortness of breath. Talking in full sentences. No recent colds or chest infection. Chest clear on auscultation, bilateral air entry, no wheeze. SpO2 97%. Respiratory rate 16b/min.

CVS: – No central chest pain. No oedema. No Hx of cardiac conditions. Regular radial pulse at 96b/min. Blood pressure 120/80 sitting Capillary Refill < 2 seconds,

CNS: – GCS 15. No headache. No dizziness. FAST Negative. Alert. Orientated to time of day, location and current situation. No neurological deficit. Blood Glucose: 5.4mmol/L. Tympanic temperature 36.3°C.

Abdo: Soft. No boarding or guarding, urine frequency and bowel movements all normal for patient

MSK: – Full range of movement in all limbs. Laceration to left lateral position on upper arm. One laceration, 5cm in length 5mm deep, tissue was normal around wound, evidence of previous lacerations. Base of sound seen, no underlying structures visible.

IMP: – Laceration to left upper arm, deliberate.

Action Plan

1. Adopt standard precautions.

2. Gain consent, introduce self and crew and reassure.

3. Gain patient and current complaint history.

4. Conduct physical examination and establish pain score.

5. Patient refused to travel to ED, Pt informed that closing the wound in situ would not be cosmetically pleasing, patient stated she knew and already had scars in the location.

6. Would cleaned with sodium chloride 0.9%

7. Lignocaine used wound closed with 4/0 suture x3

8. Wound dressed

9. Patient left in care of friend

10. told patient to pop down to local MIU in 3 days time to have the would reassessed

11. Wound care leaflet handed out and worsening advice given

This case study focusing on communication with a patient, with a brief look at shared decision making. It is a professional obligation to communicate effectively with patients, whilst registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). Communication plays an integral part of everyday living (Zumbrum, 2006).

18.6% of all complaints received by the National Health Service (NHS) were related to poor communication in 2015-2016. This period is the first time there has been a reduction in complaints since 2010. (NHS Digital, 2016).

Communication can be through speech, body language, written and touch. Successful communication requires the message to be encoded, transmitted, received and decoded by the person receiving (Chandler, 2014). Utilising the skill of instant rapport requires the clinician to quickly gain the patients trust, respect and cooperation (Lang, E. V., 2012).

To gain a patients trust it is important to introduce yourself and find out what the patient would like to be called. Using non verbal communication, maintaining eye contact, smiling and an open posture helps relax the patient. Being mindful not to encroach on a patients personal space any more than required. Once this trust is gained consent is acquired to fully assess the patient. Using active listening helps to show empathy and allows the patient to explain in their own words how they are feeling.

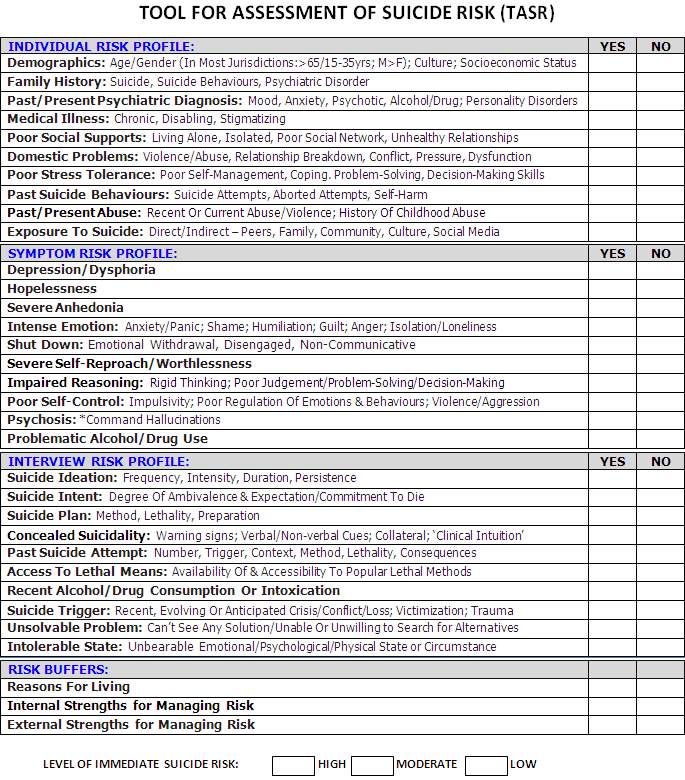

Using the capacity checklist on the electronic Patient Clinical Record (ePCR) it was deemed that the patient had capacity (Mental Capacity Act, 2005). According to Cooper, et al, (2005) this patient group is at a higher risk of suicide. In appendix one the Tool for Assessment of Suicide Risk (TASR) (British Medical Journal, 2016), is used to assess risk of suicide, this patient scored low risk. Another assessment tool for suicide risk is SAD PERSONS by Bolton, Spiwak and Sareen, (2012), is shown in appendix two. Obtaining a suicide risk score aids in the assessment of the patient and is a valuable identifier for the patients care (Sisask et al., 2009).

It is a common occurrence for people to suffer with mental health problems (Mind, 2015), research shows one in three people in the United Kingdom will suffer with mental health problems during their lifetime (NHS Digital, 2014). This patient had refused travel to an ED, she was aware of the consequences of this decision, she was advised of the possibilities of complications arising if she failed to see the staff in a local Minor Injuries Unit if a few days time. This communication and shared decision making is in line with the General Medical Council’s ethical guidance, (GMC, 2013), the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2014) and the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2006)

Shared decision making is an ethical process which is imperative for delivering high quality care (Department of Health, 2012).This process enables the clinician to work with the patient to deliver patient centred care, making the patient feel part of the process (Coulter and Collins, 2011).

In conclusion improving communication improves patient outcomes (Kurtz and Silverman, 1996, Street, 2013). Patient centred care will help patients feel like part of the process and increase job satisfaction for the clinician (Brinkman, et al, 2007; Ha and Longnecker, 2010).

References

Bolton, J,. M. Spiwak, R. and Sareen, J. (2012) ‘Predicting Suicide Attempts with the SAD PERSONS Scale: A Longitudinal Analysis’, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(6), pp. 735-741. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07362

Brinkman, W,. B. Geraghty, S,. R. Lanphear, B,. P. Khoury, J,. C. Gonzalez Del Ray, J,. A. Dewitt, T,. G. and Britto, M,. T. (2007) ‘Effect of Multisource Feedback on Resident Communication Skills and Professionalism: A Randomized Control Trial’, Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161(1), pp. 44-49.

British Medical Journal (2016) Suicide Risk Management. Available at: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/1016/diagnosis/step-by-step.html (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Chandler, D. (2014) The Transmission Model of Communication. Available at: http://visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/short/trans.html (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Cooper, J. Kapur, N. Webb, R. Lawlor, M. Guthrie, E. Mackway-Jones, K. and Appleby, L. (2005) ‘Suicide After Deliberate Self Harm: A 4-Year Cohort Study’, The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), pp. 297-303. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297

Coulter, A and Collins, A (2011) Making Shared Decision-Making a Reality. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Department of Health (2001) Psychiatric Morbidity Report. London: Office for National Statistics

Department of Health (2012) Liberating the NHS: No Decision About Me, Without me. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216980/Liberating-the-NHS-No-decision-about-me-without-me-Government-response.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

General Medical Council (2013) Consent Guidance: Sharing Information. Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_sharing_information.asp (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Ha, J,. F. and Longnecker, N (2010) ‘ Doctor-Patient Communication: A Review’, The Ochsner Journal, 10(1), pp. 38-43.

Health and Care Professions Council (2014) Standards of proficiency: Paramedics. Available at: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/1000051CStandards_of_Proficiency_paramedics.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Kurtz, S,.M. and Silverman, J,. D. (1996) ‘The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: An Aid to Defining the curriculum and Organizing the Teaching in Communication Training Programmes’, Medical Education, 30(2), pp. 83-89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00724.x

Lang, E,. V. (2012) ‘A Better Patient Experience Through Better Communication’, Journal of Radiology Nursing, 31(4), pp. 114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jradnu.2012.08.001

Mental Capacity Act 2005, c. 9. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/introduction (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Mind (2015) Mental Health Problems – an Introduction. Available at: http://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/mental-health-problems-introduction/#.V5-8-GXUH-Y (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2014) Quality Statement 6: Shared Decision Making. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs15/chapter/quality-statement-6-shared-decision-making (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

NHS Digital, (2014) Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014. Available at: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB21748 (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

NHS Digital, (2016) Data on Written Complaints in the NHS. Available at: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB21533/data-writ-comp-nhs-2015-2016-rep.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (2014) Complaints About Acute Trust 2013-14 and Q1, Q2 2014-15. Available at: http://www.ombudsman.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/28876/Complaints_about_acute_trusts_2013-14_and_Q1,-Q2_2014-15.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Sisask, M., Kolves, K. and Vamik, A. (2009) ‘Severity of Attempted Suicide as Measured by the Pierce Sucicidal Intent Scale’, Crisis, 30(3), pp. 136-143.

Street, R,. L. (2013) ‘How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modelling pathways from talk to outcome’. Patient education and Counselling, 92(3), pp. 286-291. Doi: 10.1016/j-pec.2013.05.004

World Health Organization (2006) A Process for Making Strategic Choices in Health Systems. Available at: http://www.who.int/management/quality/assurance/QualityCare_B.Def.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Zumbrum, D,. C. (2006) Effective Communication Skills for Security Personnel. Available at: http://www.ifpo.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Zumbrum_Effective_Communication_Skills.pdf (Accessed: 24 April 2017)

Appendix One

Tool for Assessment of Suicide Risk (TASR)

(British Medical Journal, 2016)

Appendix Two

SAD PERSONS

| S | Sex (male = 1, female = 0) | /1 |

| A | Age (<19yo >45yo = 1, 19yo-45yo = 0) | /1 |

| D | Depression/Hopelessness | /2 |

| P | Previous suicide attempts, DSH or Ψ care | /1 |

| E | Excessive alcohol +/- drug abuse | /1 |

| R | Rational thinking loss | /2 |

| S | Separated, divorced or widowed | /1 |

| O | Organised +/- series attempt | /2 |

| N | No social support (friends and work-colleagues) | /1 |

| S | Stated future intent or ambivalent | /2 |

| Total: | /14 |

(Bolton, Spiwak and Sareen, 2012)

Student Number: 10480521

Programme Title: BSc (Hons) Paramedic Practitioner

Module Code: PARA301

Module title: Refining Practitioner Skills for Patient Care

Faculty of Health and Human Sciences

School of Health Professions

Submission deadline date: 08 May 2017

Word Count: 538

I 10480521 declare the use of pseudonym/s within this assignment in respect of individuals and/or healthcare services. This declaration recognises the need to uphold anonymity and confidentiality where evidence related to my professional practice in healthcare is shared / disseminated

Presenting Complaint: – Head Injury

HxPC: – 45 year old male, was in his loft and hit his head on a metal beam, he had just came home from the pub and his wife had asked him to put some bits in the loft.

PMHx: – Normally fit and well

DHx: – Citalopram 40mg – one at night

SHx: – Lives at home with his wife

Allergies: – no known drug allergies

Examination:

RS: – Good colour. No shortness of breath. Talking in full sentences. No recent colds or chest infection. Chest clear on auscultation, bilateral air entry, no wheeze. SpO2 96%. Respiratory rate 16b/min.

CVS: – No central chest pain. No oedema. No Hx of cardiac conditions. Regular radial pulse at 96b/min. Blood pressure 145/85 sitting Capillary Refill < 2 seconds,

CNS: – GCS 15. No headache. No dizziness. FAST Negative. Alert. Orientated to time of day, location and current situation. No neurological deficit. Blood Glucose: 7.0mmol/L. Tympanic temperature 37.3°C. not KO’d, No C-Spine pain, Pupils PERRL size 3, normal gait, Cranial nerves two to twelve intact, 3cm Laceration to forehead, left side, just inside hair line, no swelling, no deformity or bogging. No memory loss, patient did not fall.

Abdo: no nausea urine frequency and bowel movements all normal for patient

MSK: – Full range of movement in all limbs. Patient mobilises well.

IMP: – Laceration to left forehead

Action Plan

1. Adopt standard precautions.

2. Gain consent, introduce self and crew and reassure.

3. Gain patient and current complaint history.

4. Conduct physical examination

5. Pain relief refused

6. 3cm laceration seen

7. Base of wound seen

8. Wound cleaned with sodium chloride 0.9%

9. Wound closed with glue

10. Patient given advice on would care and leaflet regarding minor head wounds.

11. Worsening advice given

12. Patient discharged at home in the care of his wife

This case study focuses on the clinical examination of a head injury. In 2014 1.4 million people were seen in Emergency Departments (ED) in England and Wales with a head injury (National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2015). Aetiology throughout England and Wales is varied, socioeconomic status, gender and age are the main variations (Jennett, 1996; Tennant, 2005; Yates et al., 2006; and Pandor et al., 2011).

Hampton, et al, (as cited in Cooke, 2012) found that 83% of patients were diagnosed correctly, which is where the aphorism “80% of diagnoses are made on patient history” came from. A further 5-10% is made on examination with the rest made on investigations (Epstein et al. 2008). Barsky, (2002) found that patients often fail to recollect correctly previous symptoms, episodes and illnesses accurately, patents underreport events and symptoms.

Neurological exams are a series of physical and cognitive tests, these provide an insight into how well the nervous system is working. This type of exam is used to assess motor and sensory skills including gait, balance, coordination, hearing, vision, speech, changes in mood, behaviour and mental status (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2015). Neurological exams performed by ambulance clinicians can be quick if clinicians have regularly used this tool however, clinicians need to be aware that rushing this could miss something.

With nearly 50% of traumatic brain injured patients being intoxicated with alcohol it is important to understand how this might affect an assessment. Stuke et al. (2007) found that using the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) on an intoxicated head injury patient compared to a sober patient, there was no clinically significant difference in GCS. GCS is used to assess and monitor the neurological status if the patient, it can be used on patients with head injuries and those with reduced levels of consciousness regardless of aetiology (Teasdale and Jennett, 1974), it can be used to aid decision making in regards to the patients treatment. GCS only has a moderate inter-rater reliability within hospital and in the pre-hospital environment, variations can also occur between health care professionals (Zuercher et al., 2009).

Cognitive and recall problems may be caused by mild traumatic brain injuries (American Academy of Neurology, 2014) with Gangavati et al., (2009), concluding that anticoagulation therapy did not raise the risk of intracranial haemorrhage, they also highlighted aspirin my afford the patient some protection however, more research is required. A study by Vilke, Chan and Guss (2000), tried to see if patients with GCS 15/15 and a normal neurological exam result could be excluded from having a Computerised Tomography (CT) scan as the risk of significant intracranial injury could be lower. They concluded that this wasn’t the case and that CT scanning should not be excluded on patients with minor head injuries despite having normal neurological exam results and a GCS of 15/15.

Using guidance from the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2014), this patient was treated and discharged back into the community. He had no loss of consciousness and no other signs or symptoms of a brain injury after a through neurological exam was carried out. Worsening advice was given.

In conclusion, when assessing minor head injuries, it is essential that clinicians have extended skills in this area, as a thorough assessment that is accurately recorded, supports the clinicians decision to discharge the patient back into the community. Due to the nature of head injuries, patients that are discharged at home must be advised of worsening signs and symptoms and know how to get help if required.

References

American Academy of Neurology (2014) Even Mild Traumatic Brain Injury May Cause Brain Damage. Available at: https://www.aan.com/PressRoom/home/PressRelease/1297 (Accessed: 01 May 2017).

Barksy, A. J. (2002) ‘Forgetting, Fabricating, and Telescoping. The Instability of the Medical History’, Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(9), pp. 981-984. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.9.981.

Cook, G., (2012) A is for aphorism Is it true that ‘a careful history will lead to the diagnosis 80% of the time’?, Australian Family Physician, 41(7). pp. 534-534 Available at: http://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2012/july/a-is-for-aphorism/

Epstein, O., Perkin, G.D., Cookson, J., Watt I. S., Rakhit, R., Robins, A. W. and Hornett, G. A. W. (2008) Clinical Examination. 4th edn. Phillidelphia: Mosby Elsevier.

Gangavati, A. S., Kiely, D. K., Kulchycki, L. K., Wolfe. R. E., Mottley. J. L., Kelly. S. P., Nathanson. L. A., Abrams, A.P, and Lipsitz. L.A. (2009) ‘Prevalence and Charateristics of Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage in Elderly Fallers Presenting to the Emergency Department Without Focal Findings’, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(8), pp. 1470-1474. doi: 10.111/j.1532-5415.2009.02344.x.

Hills. L. (2010) ‘Defusing the Angry Patient: 25 tips’, The Journal of Medical Practice Management. 26(3), pp. 158-160.

Jennett, B. (1996) ‘Epidemiology of Head injury’, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry’, 60, pp. 362-369.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2014) Pre-hospital assessment, advice and referral to hospital. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg176/chapter/1-recommendations#pre-hospital-assessment-advice-and-referral-to-hospital (Accessed: 01 May 2017).

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2015) Head Injury: Assessment and Early Management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg176/chapter/introduction (Accessed: 01 May 2017).

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (2015) Neurological Diagnostic Tests and Procedures. Available at: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/misc/diagnostic_tests.htm#tests (Accessed: 01 May 2017)

Office for National Statistics (2015) Crime in England and Wales: Year ending March 2015. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/2015-07-16#violent-crime. (Accessed: 01 May 2017)

Pandor, A., Goodacre, S., Harnan, S., Holmes, M., Pickering, A., Fitzgerald, P., Rees, A. and Stevenson, M. (2011) ‘Diagnostic Management Strategies for Adults and Children with Minor Head Injury: A Systematic Review and an Economic Evaluation’, Health Technology Assessment, 15(27), pp. 1-202.

Stuke.L., Diaz-Arrastia. R., Gentilello. L. M. and ShafI. S (2007) ‘Effect of Alcohol on Glasgow Coma Scale in Head-Injured Patients’, Annals of Surgery. 245(2), pp, 651-655. doi: 10.1097/01sla.0000250413.41265.d3.

Teasdale.G. and Jennett. B (1974) ‘Assessment of Coma and Impared Consciousness: A Practical Scale’, The Lancet, 7872(2), pp. 81-84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0.

Tennant, A (2005) ‘Admission to Hospital Following Head Injury in England: Incidence and Socio-Economic Associations’, Biomed Council, 5(21), pp. 1-8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-21.

Vilke. G. M., Chan. T. C. and Guss, D.A. (2000) ‘Use of a Complete Neurological Examination to Screen for Significant Intracranial Abnormalities in Minor Head Injury’, The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18(2), pp. 159-163

Yates, P. J., Williams, W. H., Harris, A., Round, A. and Jenkins, R. (2006) ‘An Epidemiological Study of Head Injuries in a UK Population Attending an Emergency Department’, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 77(5), pp. 699-701.

Zuercher, M., Ummenhofer, W., Baltussen, A. & Walder, B. (2009) ‘The use of Glasgow Coma Scale in injury assessment: a critical review’, Brain injury, 23(5), pp. 371-384.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Healthcare"

Healthcare is defined as providing medical services in order to maintain or improve health through preventing, diagnosing, or treating diseases, illnesses or injuries.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: