Pathways to Resilience in the Context of Somali Culture and Forced Displacement

Info: 48730 words (195 pages) Dissertation

Published: 28th Feb 2022

Tagged: Cultural StudiesPsychology

Abstract

Little is known about resilience among Somali refugees. This study employed a participatory, sequential, mixed-method research design to: a) culturally adapt and validate the Resilience Research Center- Adult Resilience Measure (RRC-ARM) for use with Somali people; and b) Explore pathways to resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement.

The study was completed in three phases. First, interviews were conducted with resilient Somali people (n = 10) living in the US. These interviews produced information about Somali conceptualizations of resilience and informed selection of study measures administered during phase three. Second, study measures were translated and back-translated. Third, a quantitative survey of resilience, life difficulties, well-being, and meaning in life was administered to 137 Somali people living in the US.

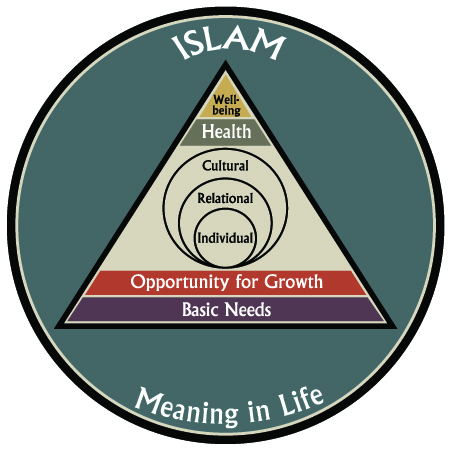

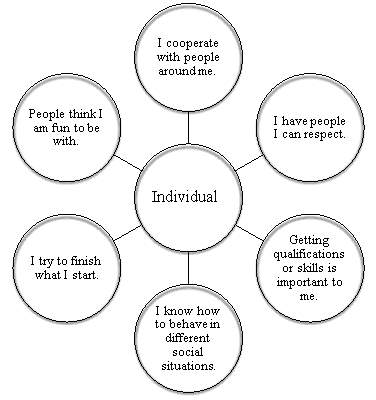

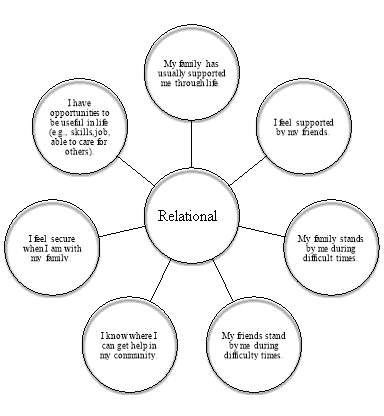

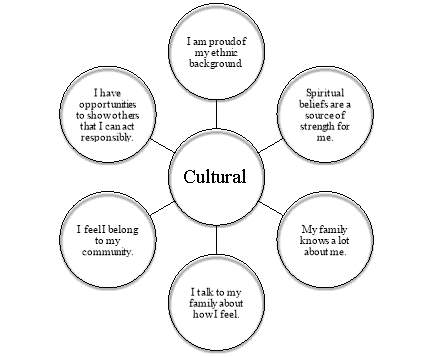

An exploratory factor analysis of the RRC-ARM produced a three-factor structure (viz., individual, relational, and cultural) with good internal consistency and convergent validity. Evidence was also found to support the incremental validity of the measure. Resilience positively associated with presence of meaning in life; and meaning in life predicted a good portion of variance in well-being. The qualitative findings suggest that “presence of meaning in life” is reflective of the broader influence of Islam on understanding life experiences in the context of Somali culture; and resilience resides within broader geographic and political contexts that influence access to resources that promote health and well-being. Qualitative and quantitative findings were integrated to develop the Somali Multidimensional and Multilevel Resilience (SMMR) model. Key elements of the model include the factors that emerged from EFA and a hierarchy of health-sustaining resources, all nested in a form of existential resilience experienced through Islam and presence of meaning in life.

The Somali RRC-ARM seems to be a psychometrically sound measure of resilience with Somali people. Complementing administration of the Somali RRC-ARM with qualitative data is essential for proper interpretation of quantitative data. The SMMR Model provides a framework from which to assess resilience factors across multiple dimensions and multiple levels across a variety of contexts and promotes strengths-based programming and practice.

Chapter 1: Introduction

This study employed a participatory, sequential, mixed-method (qualitative-quantitative) research design to explore resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement. The research design ensures that quantitative data reflected the underlying cultural and contextual realities of Somali refugees. Qualitative information provided context to quantitative data. Cultural advisors contributed to research design, methodology, selection of culturally relevant measures of variables that may be theoretically related to resilience, and interpretation of study findings. Researchers and research assistants worked closely with professional consultants, cultural advisors, and community partners to produce the first psychometrically sound measure of resilience for Somali refugees and the Somali Multidimensional and Multilevel Resilience Model. This chapter presents the background and significance of studying resilience in the refugee context is presented, followed by an overview of research design and methodology. The chapter closes with a problem statement and presentation of research questions and study aims.

Background and Significance

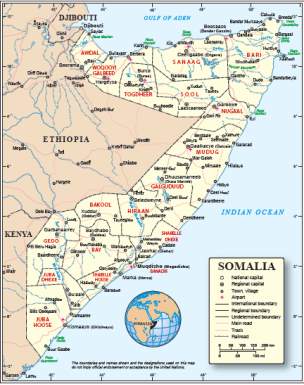

Figure 1: Map of Somalia

Somalia is a country located in the northeastern corner of Africa in a region commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa (Google Maps, 2013). In 1991, local rebel groups overthrew the government of Somalia. Mogadishu and most of southern and central Somalia disintegrated into civil war. Simultaneously, a deadly drought settled over the region (Abdullahi, 2001). With no formal government in place, food and power belonged to those with guns (Putnam & Noor, 1993). Over the course of one year, hundreds of thousands of Somali people died from political violence, disease, and famine. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), by August 1992, about one fourth of the population of Somalia was in danger of starvation. At least 40% of the population in the city of Baidoa died between August and November, and various relief organizations estimated that one half of all Somali children under five years old had died (CDC, as cited by Putnam & Noor, 1993). Conflict in Somalia continues today, especially in central and southern regions of the country. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR; 2010), about 1.4 million people are internally displaced within Somalia and over 600,000 Somali people have taken refuge in Kenya and Ethiopia.

High rates of exposure to adversity among Somali refugees are well documented. The most commonly reported adverse experiences include political violence, death of loved ones, torture, rape, and starvation (Bhui et al., 2003). Conditions in refugee camps are only slightly better than Somalia. Food and water are in short supply, security is minimal, and livelihood opportunities are nearly non-existent in refugee camps (Ingleby, 2005). Many Somali refugees spend years, even decades in refugee camps, waiting for a durable solution to their crisis. Only small fractions of people are considered for resettlement in a third country. Those who are resettled in a third country encounter additional forms of adversity, including acculturation stress and racial discrimination (Young, 2006).

Research suggests Somali refugees experience high rates of physical illnesses (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, chronic pain) and mental health disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, PTSD) following resettlement (Bentley & Olson, 2008; Halcón et al., 2004; Jaranson et al., 2004; Robertson et al., 2006). According to Bentley and Olson (2008), Somali refugees rarely seek mental health treatment due to social stigma and differences in conception of mental disorder across cultures.

Western culture views mental health from the perspective of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). According to the DSM-IV, individuals experience a range of thoughts, emotions, memories, and sensory experiences that combine to create general psychological experience. Love, grief, anxiety, sadness, stress, posttraumatic stress, intellectual disorders, and developmental disabilities are dimensions of psychological experience considered within the Western conception of mental health and illness (Arnett, 2012). Seeking mental health services is not uncommon in Western culture and services include a range of approaches from brief psychotherapy to long-term, residential treatment (Pomerantz, 2010).

In comparison, Somali culture views mental health more dichotomously: one is either sane or insane (Bentley & Olson, 2008). The sane may experience many conditions Western culture labels as disordered, such as sleep disturbance, nervousness, fatigue, headache, and sadness. Traditionally, Somali people consider these types of experiences a normal part of life, spiritual challenges to overcome. Mental disorders are highly stigmatized in Somalia. Families often isolate and care for the insane alone, or the individual is hospitalized indefinitely (Bentley & Olson, 2008).

Some researchers have sought to understand barriers to help-seeking behavior among refugee populations in general (Ingleby, 2005), such as communication difficulties and lack of understanding of the healthcare system in the US. Public health initiatives have focused on decreasing stigma associated with mental disorders among diverse populations in an effort to boost help-seeking behavior (Henderson, Evans-Lacko, & Thornicroft, 2013). These efforts rest on at least two assumptions: a) Western mental health services are the best avenue for addressing mental distress among Somali refugees; and b) correcting Somali conceptions of mental disorder will lead to increased engagement in the context of traditional Western mental health services. Given the choice, however, it seems most Somali people prefer to cope with mental health concerns within the family system and through spiritual practice and prayer (Bentley & Olson, 2008).

According to Luthar, Cicchetti, and Becker (2000), “resilience refers to a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (p. 543). The construct offers an alternative lens through which to consider health and well-being. Resilience research began in the early 1980s when researchers first became interested in the subpopulations of peoples who were adapting and developing well despite the experience of adversity. A robust body of literature on resilience has developed since that time, contributing to an understanding of individual and environmental dimensions of the construct (Anthony & Cohler, 1987; Garmenzy, Masten, & Tellegen, 1984; Kobasa, 1979; Luther et al., 2000; Scales & Roehlkepartain, 2003; Werner & Smith, 2001).

This literature has developed, however, with little attention paid to the role of cultural and contextual factors in the understanding, expression, and experience of resilience (Liebenberg & Ungar, 2009). The study of resilience presents an alternative avenue for understanding health and well-being among Somali populations that is focused on strengths as opposed to deficits and disorders. Most quantitative measures of resilience, however, were developed based on Western cultural norms and assumptions. Indeed, out of 15 measures of resilience identified in a literature search of the EBSCO database (see Appendix A), only one measure, the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM), was developed and validated for use cross-culturally (Ungar & Liebenberg, 2011).

The CYRM was developed by the International Resilience Project (IRP), which is a part of the Resilience Research Center (RRC) located at Dalhousie University in Fairfax, Nova Scotia. Drs. Michael Ungar and Linda Liebenberg are co-directors of the research center and principal investigators on the IRP, a multisite, cross-cultural investigation of resilience among children living in developing nations and children living among marginalized populations within developed nations (Ungar & Liebenberg, 2009).

Using an iterative and participatory model of mixed-method research to investigate resilience, IRP brought together over 40 researchers across 14 research sites in 11 countries. They developed and pilot-tested the innovative CYRM across the 14 research sites, analyzed findings from the administration of the CYRM to 1451 youth globally, collected 89 interviews and life histories from children across sites, conducted 5 focus groups with youth and 12 interviews with adults in different communities, and collected field notes on the process of the study design.

The IRP predicted the CYRM to sort into an ecological model similar to that proposed by Bronfrenbrenner (1979), but the researchers were unable to produce a valid and stable factor structure across all cultures and context. Scores did not sort neatly into the hypothesized model. Qualitative data helped contextualize differences observed across cultures. Ungar (2008) concluded that cultural context shapes how ecological components of resilience (e.g., family, community) contribute to the expression of resilience. Therefore, qualitative and quantitative methods alone cannot capture resilience completely, which suggests mixed-methods are necessary. Indeed, Ungar and Liebenberg (2011) recommend complementing quantitative data with qualitative inquiry and participant input to ensure the validity of data interpretation. The RRC recently adapted the CYRM for use with adult populations (Liebenberg, 2011, personal communication), resulting in the RRC-Adult Resilience Measure (RRC-ARM; Liebenberg, 2012, personal communication).

The present study is theoretically aligned with the work of the RRC and IRP. Following Ungar and Liebenberg’s (2011) recommendations, this study employed a partially participatory, sequential, mixed-method research design to:

- Explore the factor structure, construct validity, and clinical utility of the RRC-ARM when administered to a Somali population;

- Examine pathways to resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement.

The following definition of resilience guided our inquiry:

In the context of exposure to significant adversity, whether psychological, environmental, or both, resilience is both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to health-sustaining resources, including opportunities to experience feelings of well-being, and a condition of the individual’s family, community and culture to provide these health resources and experiences in culturally meaningful ways (Ungar, 2008, p. 225).

Research Design and Methodology

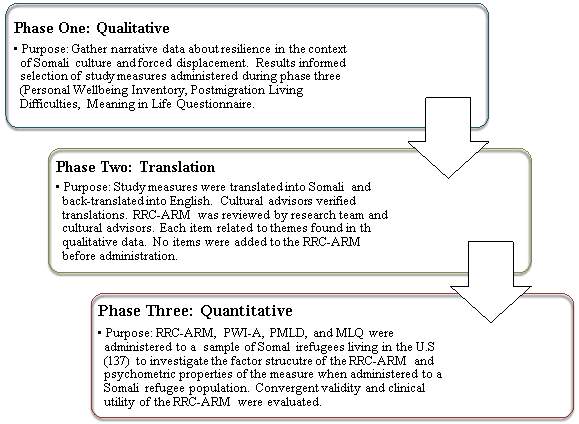

This study employed a participatory, mixed-method research design in three phases. During phase one, the research team conducted interviews with resilient Somali people (n = 10) living in the US about experiences of health and well-being in the context of adversity across three distinct contexts (i.e., Somalia, refugee camps, US). These interviews produced information about Somali conceptualizations of resilience and informed selection of study measures (with support of the cultural advisors) to be administered during phase three. During phase two, study measures were translated and back-translated in an iterative process until deemed culturally equivalent by translators and cultural verifiers. During phase three, a quantitative survey of resilience, life difficulties, well-being, and meaning in life was administered to 137 Somali people living in the US. Qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed separately and then integrated to develop a multidimensional model of resilience for Somali refugees.

Cultural advisors

Ungar and Liebenberg (2009) recommended collaborating with cultural advisors and community members when researching resilience. Our research team included three cultural advisors with whom we collaborated on each phase of the study. Cultural advisors were chosen because of their own experience overcoming adversity and their understanding of Somali culture, language, and community, and their interest in the project.

Cultural advisors were involved in:

(1) the conceptualization of the research project;

(2) the development of the key-informant interview protocol;

(3) conducting key-informant interviews;

(4) selecting, translating, and adapting study measures;

(5) consulting on the survey format;

(6) connecting the project with community organizations who helped facilitate quantitative data collection;

(7) general cultural navigation; and

(8) the interpretation and presentation of research findings.

Meetings were held as needed, most typically in the form of telephone conversations, followed by email communications. Many other Somali community members, as well as many academic and professional consultants, were less formally involved in shaping the project.

Problem Statement and Study Aims

Somali people form one of the largest and fastest-growing refugee populations in the world (UNHCR, 2010). Research documents extremely high rates of exposure to adversity among Somali refugees, including political violence, death of loved ones, torture, rape, and starvation (Schuchman & McDonald, 2004). Likewise, many researchers have observed high rates of psychopathology among Somali refugees following resettlement (Halcón et al., 2004 Jaranson et al., 2004; Robertson et al., 2006). Despite high rates of exposure to adversity and high rates of psychopathology (e.g., PTSD, depression), Somali refugees often are reluctant to utilize Western mental health services (Bentley & Olson, 2008). The academic literature disproportionately focuses on pathology, as defined by Western cultural norms and expectations, with little attention paid to resilience among Somali refugees. Resilience may be an alternative avenue toward understanding and promoting well-being among Somali refugees living locally and globally. However, a measure for examining resilience among Somali refugees has not yet been validated, and little is known about how resilience is conceptualized among Somali people.

To begin to address these gaps in the literature, and elucidate pathways to resilience among Somali refugee populations, the present study:

- Qualitatively explored resilience and well-being among Somali refugees using key-informant interviews;

- Identified additional study measures based on qualitative findings and consultation with cultural advisors;

- Translated and back-translated all study measures;

- Administered a survey of resilience, life difficulties, personal well-being, and meaning in life to a purposive sample of Somali people living in the US;

- Produced data on the factor structure and psychometric qualities of the RRC-ARM when administered to a Somali population; and

- Integrated qualitative and quantitative data into a multidimensional model of resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Global Refugee Crisis

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) documented 43.7 million forcibly displaced persons living worldwide at the close of 2010 (UNHCR, 2010). The organization cited political violence and persecution as the driving force behind displacement. This is the highest reported number of forcibly displaced persons in over 15 years. To aid in comprehension of the following literature review, I will use the term refugee broadly to include all seven UNHCR categorizations of forcibly displaced persons: refugee, asylee, internally displaced person, stateless person, returned refugee, returned internally displaced person, and others of concern. These categories are described here to offer an appreciation for the breadth of experiences encompassed by the global refugee crisis.

Forcibly displaced populations

According to Article 1A of the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, a refugee is a person who:

Owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owning to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country (UNHCR, 1951, p. 1, as cited by UNHCR, 2012).

An asylee is defined exactly as a refugee in the definition above. Unlike refugees, however, asylum seekers arrive in the host country before they have evaluated the asylum claim. Refugees typically arrive in host countries en masse from known conflict areas. UNHCR grants asylum upon registration at the refugee camp. Asylum seekers must prove they have a well-founded case constituting designation as a refugee before they are granted asylum in the host country. This process results in legal fees, living under the threat of forced repatriation to their country of origin, and at times, indefinite confinement (Ingleby, 2005). Once granted asylum, asylees share similar access to immigration and social services as refugees.

An internally displaced person (IDP) is one who is displaced within the borders of their home country due to war, persecution, or natural disaster. IDPs are officially nationals of their home country, and their home government is officially responsible for their protection. IDPs are often displaced due to government-fueled war or persecution, placing their very protection in the hands of their persecutors. IDPs are particularly vulnerable populations. They are difficult to access due to their dispersion in war torn areas, making aid and other service delivery challenging. Although the number of IDPs is difficult to estimate, UNHCR (2012) reported over 27.5 million IDPs received their assistance in 2010. This is the highest number of IDPs ever recorded; nearly double the figure from 2005 (UNHCR, 2012).

A stateless person is one who lives without formally acknowledged nationality or citizenship in any State. Statelessness occurs for many reasons, including discrimination against minority groups in nationality legislation and failure to include all citizens when states declare independence. Stateless persons live on the fringes of society, often unable to obtain documentation of their identity. Without identification, stateless persons are often detained and denied access to education and health care services. About 12 million stateless people live worldwide (UNHCR, 2010).

Returned refugees and returned IDPs are the populations of people who are able to return to their country of origin to an environment deemed adequately safe by the UNHCR. Only 197,600 refugees were returned to their country of origin in 2010, the lowest number in two decades. This low number is offset by the 2.9 million IDPs returned to their home communities in 2010, the highest number on record in 15 years. Others of concern are a UNHCR category of displaced persons who do not fit one of the previous definitions of forced displacement but still receive aid or benefits from UNHCR programming (UNHCR, 2012).

Durable solutions

After fleeing persecution, many refugees spend years, even decades in refugee camps, waiting for a durable solution to their crisis. The UNHCR outlines three durable solutions for forcibly displaced populations: a) repatriation to their country of origin; b) integration into the local (host) community; or c) resettlement in a third country.

Repatriation has steadily decreased since 2004. As previously noted, only 197,600 refugees were returned to their homes in 2010, the lowest number reported in two decades. Integration into the local (host) community is uncommon due to a constellation of legal, economic, and sociocultural challenges (UNHCR, 2010). Finally, less than 1% of the total refugee population resettles in a third country (Ingleby, 2005).

Resettlement has slowed in recent years due to increased security measures and screening protocols for refugees seeking resettlement (UNHCR, 2010). In 2010, the UNHCR submitted more than 108,000 refugee cases for consideration; 22 countries accepted refugees for resettlement and only 98,800 refugees were resettled. Many refugees find themselves in protracted situations, defined by the UNHCR as:

Situations in which refugees find themselves in a long-standing and intractable state of limbo. Their lives may not be at risk, but their basic rights and essential economic, social and psychological needs remain unfulfilled after years of exile (UNHCR, 2006, p. 106).

One such situation is evident along the borders of Somalia where 70,000 Somali refugees have fled to neighboring countries in the past year alone, contributing to the world’s largest protracted refugee crisis (UNHCR, 2011).

Somali refugees

Somali refugees comprise one of the largest and fastest growing refugee populations in the world (UNHCR, 2011). Following the fall of government in 1991, Somalia has been in a brutal civil war, prompting large numbers of men, women, and children to flee the country seeking refuge in bordering countries (Putnam & Noor, 1993). Many other Somali people remain displaced within Somalia’s borders (UNHCR, 2011).

Due to ongoing political violence and famine, the UNHCR and other humanitarian aid organizations reported a dramatic increase in the number of Somali refugees in recent years (Médicins Sans Frontières, 2009; UNHCR, 2011). Since 2008, over 120,000 Somalis have entered Kenya as refugees, and over 70,000 new Somali refugees have arrived in Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, making the camp the largest in the world (UNHCR, 2011).

The UNHCR originally established Dadaab to accommodate 90,000 refugees. It is now over three times that capacity, and more than 5,000 refugees continue to arrive at the camp monthly—exhausted, malnourished, and in need of immediate medical attention (Médicins Sans Frontières, 2009). According to the UNHCR (2011), Dadaab represents a protracted refugee situation and one of the most acute emergencies in the world.

Mental health of refugees

Global concern for the mental health of refugees has increased in recent years. Policy makers and healthcare providers are increasingly recognizing mental healthcare as a priority for many refugees (Ingleby, 2005). Many studies document high prevalence of mental health disorders among refugee populations. Refugees experience high rates of mental disorders due to a constellation of pre-migration and post-migration stressors. The body of literature reflects studies conducted with refugee populations since the early 1980s. Researchers in Western academic institutions have conducted most studies on refugee mental health, such as The Harvard Trauma Center, which developed the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) and adapted the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL) for use with refugee populations. Researchers consider these measures the gold standard screening measures for PTSD, anxiety, and depression among refugee populations. The HTC and HSCL have demonstrated good reliability across many studies (Bentley, 2011; Jaranson et al., 2004; Mollica et al., 2002).

All of these studies, however, must be understood within the context in which they occurred. Most studies of refugee mental health impose a Western model of disorder without careful consideration of cross-cultural validity. Measurement tools are most often developed by Western researchers and validated among large samples of Western participants. When these tools are translated and administered to non-Western populations, researchers must take caution to ensure the validity of data. Translation and back-translation is an iterative and active process. Researchers seldom explain thoroughly how and why the measure was deemed equivalent in meaning across cultures.

History of refugee mental health research

Early contributions to the refugee mental health literature came during the 1980s when Southeast Asian populations (viz., Cambodian, Vietnamese, and Hmong/Laotian) first resettled in the West. Researchers conducted a longitudinal study of PTSD among a group of Cambodian youths (n = 46) who had endured internment in Khmer Rouge re-education camps (Kinzie, Sack, Angel, Clark, & Rath, 1989; Sacks, Angle, Kinzie, & Rath, 1986). The Pol Pot regime subjected these youths to forced labor, beatings, and starvation. Each lost an average of three family members due to the violence. Four years after departure from Cambodia, over 50% met diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Kinzie et al., 1986). At three-year follow up, the researchers found nearly identical rates of PTSD (Kinzie et al., 1989). Unfortunately, they were unable to determine whether the same youths experienced the disorder, or if there were unique cases.

Mollica and colleagues (1993; 2002) published a group of studies documenting rates and correlates of PTSD and depression among Southeast Asian refugee populations. They conducted one study in a Thai refugee camp. Over 50% of Cambodian refugees (n = 993) met diagnostic criteria for depression, and an additional 25% met criteria for PTSD. Most refugees reported experiencing multiple acts of violence, loss, and deprivation (Mollica et al., 1993). McSharry and Kinney (1992) documented a 43% prevalence of PTSD among Cambodian refugees (n = 124) after living in the US between 12 and 14 years. Mollica and colleagues (1993) measured trauma exposure and PTSD symptomatology among a sample of Vietnamese survivors of torture (n = 51). They found 90% met diagnostic criteria for PTSD and another 49% met criteria for depression (Mollica et al., 1993). Mollica and colleagues (1993) point to a link between intensity of torture experienced by the individual (as indicated by the number of traumatic events endorsed) and severity of PTSD symptomatology.

Many researchers have described a dose-response relationship between trauma exposure and PTSD (Friedman, Keane, & Resick, 2007) and several have documented the phenomenon among refugee populations. Thabet and Vostanis (2000), for example, examined traumatic events and PTSD among a sample of Palestinian children living in the Gaza Strip. They found a positive relationship between the number of traumatic events experienced by the children and severity of PTSD symptomology. Forty-one percent of the sample met criteria for PTSD. Smith and colleagues (2008) conducted a large study on the mental health of Bosnian children (n = 3000) living in southern Bosnia-Herzegovina. They found an estimated PTSD prevalence of 52% and reported the degree of exposure to war related violence was the strongest predictor of PTSD.

El Sarraj, Pumamäki, Salmi, and Summerfield (1996) documented a 20% prevalence of PTSD among torture survivors living in Gaza. Shrestha and colleagues (1998) documented significantly higher rates of PTSD, anxiety, and depression among Bhutanese refugees (n = 526) compared to matched controls both living in Nepal. Researchers documented high rates of PTSD among: Central American adult refugees (Michultka, Blanchard, & Kalous, 1998), Sierra Leonean refugees living in the Gambia (Fox & Tang, 2000), and Sudanese refugee women (Kim, Torbay, & Lawry, 2007) and children (Paardekooper, de Jong, & Hermanns, 1999).

Pre-migration and post-migration stressors

Porter and Haslam (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of pre-migration and post-migration stressors associated with mental health outcomes of refugees. They documented significant pre-migration predictors of mental health outcomes including: age at the time of displacement (younger refugees seem to fare better than older refugees); gender (male refugees seem to fare better than female refugees); region of displacement (refugees displaced from urban areas seem to fare better than refugees displaced from rural areas); educational level (refugees with lower levels of formal education seem to fare better than refugees with higher levels of education); and socioeconomic status (refugees with lower pre-migration socioeconomic status seem to fare better than refugees with higher pre-migration socioeconomic status).

They also documented significant post-migration predictors of mental health outcomes including: living accommodations (refugees with permanent, private accommodations seem to fare better than refugees with institutional or temporary, private housing); economic opportunity (refugees with access to employment and ability to maintain pre-migration socioeconomic status seem to fare better than refugees with limited access to employment and marked loss of socioeconomic status); locus of displacement (externally displaced refugees seem to fare better than internally displaced refugees); repatriation status (permanently resettled refugees seem to fare better than repatriated refugees); and the stage of the conflict (refugees from conflicts that have since been resolved seem to fare better than refugees from conflicts that are ongoing). Refugees also report a multitude of migration stressors including loss of loved ones, shortage of food and basic necessities, exposure to war-related violence, and torture (Porter & Haslam, 2005).

Somali mental health

Like other refugee populations, Somali refugees experience high rates of exposure to adversity and are at risk for developing mental health disorders. Research has revealed generally high rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among Somali refugees. Roodenrijs, Scherpenzeel, and de Jong (1998) conducted one of the first studies on mental health disorders among Somali refugees. They measured symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in relation to the number of traumatic events experienced among Somali refugees (n = 54) resettled in the Netherlands and found that the most prevalent disorders were depression (63%), anxiety disorder (36%) and PTSD (31.5%). Depression and PTSD were comorbid in 7.5% of the sample. Pre-migration trauma strongly related to post-migration depression, anxiety, and PTSD, but no significant correlations were found between the number of traumatic events experienced and subsequent psychopathology.

Similarly, Bhui and colleagues (2003) studied traumatic events, migration characteristics, and psychiatric symptoms among 180 Somali refugees living in the U.K. About 22% of women and 28% of men met diagnostic criteria for comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders. Cumulative pre-migration trauma was a risk factor for both anxiety and depression. Traumatic experiences commonly associated with psychological distress included food shortage and being in a war-like situation. They found torture to be a non-significant contributor to psychopathology. In fact, individuals who were exposed to combat or imprisonment actually exhibited a lower risk for depression, anxiety, and suicide in this study. Bhui and colleagues suggested the findings might reflect resilience factors not yet represented in the literature (Bhui et al., 2003).

Jaranson and colleagues (2004) conducted an epidemiological study of torture prevalence and related problems among a community-based sample of Somali and Oromo refugees (n = 622) living in the Midwest US. They found a 36% prevalence of torture among the sample, a higher rate of torture than typically reported in the literature. Women reported torture experience as often as men and all but six participants reported traumatic experiences. Both trauma and torture positively associated with social, physical, and psychological problems. Social problems were more common among women and individuals who reported decreased religious practice. Social problems were less common among individuals with English language fluency, who had a high school diploma/GED, who had lived in the US longer, who were employed, and those who were homeowners.

Halcón and colleagues (2004) investigated life circumstances, health, and trauma history among a sample of Somali and Oromo youth (n =338) living in the US. Overall, they found higher rates of trauma exposure strongly associated with psychological and physical difficulties but only weakly associated with an increase in social problems. Men reported more physical and PTSD complaints than women, whereas women endorsed more social problems. Robertson and colleagues (2006) found that symptoms of PTSD among Somali and Oromo women (n = 459) significantly correlated with older age, a larger family, an absent spouse, and caring for children while living alone.

Bhui and colleagues (2006) examined anxiety, depression, and PTSD among a sample of Somali refugees (n = 143) in the early stages of resettlement in the U.K. They were interested in rates and correlates of comorbid anxiety and depression and PTSD. About 35% of the sample met criteria for anxiety or depression (referred to by the authors as common mental disorders) and 14% met criteria for PTSD. The researchers noted higher risk of mental disorders among asylees, users of khat (a flowering plant native to the horn of Africa that is chewed for stimulant-like effects), and recruits from primary care settings. They found lower risk of mental disorder among individuals who were educated and employed. Overall, 30% of participants met criteria for a depressive disorder and 80% of participants who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD also met criteria for anxiety or depression. These findings suggest that the comorbidity of depression, anxiety, and PTSD is so high that it is difficult to measure them as discrete disorders among Somali refugee populations.

Cross-cultural comparison studies

Cross-cultural research comparing rates of psychopathology among Somali refugees to other refugee populations is slight, but interesting. Strutters and Ligon (2001), for example, found anxiety to be highest among Somali refugees when compared to refugees from either Yugoslavia or Vietnam. Gerritsen and colleagues (2006) compared rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD between three groups of refugees and asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Iran, and Somalia and found that while Somali refugees and asylum seekers experienced the greatest number of traumatic events (M = 7.6, SD = 3.9), they also reported the lowest levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Among all refugee groups, however, an increase in the number of traumatic events experienced was associated with an increase in psychological distress; greater post-migration stress; and low social support was also related to increased anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic symptomology (Gerritsen et al., 2006).

Kroll, Yusuf, and Fujiwara (2011) examined PTSD, psychosis, and depression among an outpatient clinical sample of 600 Somali refugees living in the US. They compared prevalence of these disorders to a cohort sample of 3,009 non-Somali patients after observing a seemingly high rate of Somali refugees reporting psychotic symptomology. Overall, Somali refugees experienced significantly higher rates of depression and psychosis compared to non-Somali patients, while rates of PTSD did not differ significantly between the two groups. Interestingly, 80% of Somali men under age 30 in the sample were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. These rates decreased with age; about 40% of Somali men ages 31-50 were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder and only 8% of men over age 50 were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. Somali women were diagnosed with psychosis at a much lower rate (32%). This rate, however, was still significantly higher in Somali women compared to non-Somali women (14%) in the sample. In the same study, only 3% of Somali men under the age of 30 met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. This number increased with age resulting in 15% prevalence among men over 50 years old. Likewise, only 9% of women in the study met criteria for PTSD, with the prevalence rate remaining relatively stable across age groups.

The authors explained the low rates of PTSD were likely due to young Somali men’s reluctance to acknowledge or discuss past traumas. When trauma was acknowledged, the authors described a strong denial of emotional impact or lasting effects of witnessing or experiencing the traumatic event. Men and women alike denied sexual violence against women despite contrary evidence elsewhere in the literature (Jaranson et al., 2004).

Post-migration adaptation

Post-migration adaptation is a key factor in psychological well-being after resettlement (Ingleby, 2005). Political, social, physical, and psychological factors may prevent refugees from adapting to life in their host country. The process of relocation puts refugees at risk for problems due to stress, acculturation problems, employment status, individual personality characteristics, and traumatic experiences during the various stages of migration (Bhugra, 2004; Williams & Berry, 1991). Several studies have pointed to post-migration mobility in the host country as a significant factor associated with mental-health status of Somali refugees (Palmer, 2006; Warfa et al., 2006). For example, changes in residential status within the first five years for Somali refugees living in the U.K. was strongly related to depression after controlling for area of residence, age, and gender (Warfa et al., 2006). Moreover, Silveira and Allebeck (2001) linked loss of social status (e.g., vocational status) to increased depression in older Somali male refugees.

Young (2006) examined the role of acculturation in psychological adjustment among a sample of Somali refugee women living in Canada. She found a longer residence in Canada related with increased perception of discrimination, both individually and collectively as a Somali. Finally, Halcón and colleagues (2004) studied the current living situations of 140 Somali refugees living in the US and found that 21% of males and 6% of females reported living alone, 51% of men and 38.5% of women participants reported problems getting a job, and half of men and nearly half of women reported difficulty adjusting to life in the US. Nearly half of all women and one-third of all men in the sample reported feeling alone since migration. The majority of Somali participants, however, reported receiving more respect in the US than in Somalia, and about 80% reported having made the correct choice in migrating to the country.

Although protective factors have not been the focus of any quantitative study of Somali refugees, several studies have alluded to potential protective factors that may buffer the impact of risk factors on the development of mental health disorders. Bhui and colleagues (2006), for example, found that greater educational experience and employment in the host country related to lower risk for anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Halcón and colleagues (2004) reported that fluency in English, immigration at a younger age, immigrating to the US with a family member, and a longer time living in the US all significantly related to lower PTSD scores among Somali refugees. Moreover, Silveira and Allebeck (2001) identified support from their family, interaction with peers, and engagement in religious practices as protective factors against depression for Somalis.

In sum, the UNHCR documented 43.7 million forcibly displaced persons living worldwide at the close of 2010 (UNHCR, 2010). Refugees experience high rates of mental disorders and social problems due to a constellation of pre-migration and post-migration stressors and psychological tendencies. Many factors seem to contribute to poor mental health outcomes, including age, gender, region of displacement, educational level, socioeconomic status, living accommodations, economic opportunity, locus of displacement, repatriation status, and stage of the conflict. Post-migration adaptation is a key factor in psychological well-being after resettlement (Ingleby, 2005). Political, social, physical, and psychological factors may promote or hinder adapting to life post-migration. Although protective factors have not been the focus of any quantitative study of Somali refugees, several studies have alluded to potential protective factors that may buffer the impact of risk factors on the development of psychopathology.

Resilience is a term used to capture the processes, predictors, and outcomes related to positive adaptation in the context of adversity. Instead of focusing on problems and disorders, resilience focuses on solutions and health promotion. The following section presents a brief history of resilience research, cultural and contextual considerations for the study of resilience, and an overview of the IRP.

Resilience

The term resilience comes from the Latin word resile, which means “to leap back.” Early conceptualizations of resilience typically emphasized individual or individually mediated factors associated with positive outcomes in the context of adversity (e.g., Anthony & Cohler, 1987). Anthony and Cohler’s (1987) work on ego-resilience marks the early research on the construct. Ego-resilience is a multidimensional personality trait largely dependent on intellect and behavioral temperament (e.g., a sunny disposition) and expressed through one’s ability to see multiple perspectives, plan for the future, express creativity, and maintain a sense of humor—even in the context of adversity (Anthony & Cohler, 1987).

Confusion between the term ego-resilience and resilience more broadly defined has contributed to criticism of the construct as a tautology. Indeed, ego-resilience is closely related to the personality construct hardiness (Kobasa, 1979), and measurement in this context offers little additional information outside of this well-established psychological construct (Waaktaar & Torgersen, 2010). Much of the research on ego-resilience, therefore, falls outside of the parameters of contemporary conceptualizations of resilience, as the narrow conceptualization largely overlooks the potential influence of environmental factors. Longitudinal research, however, has elucidated the role of environmental factors on development of psychopathology in addition to individual-level factors.

Brief history of resilience research

Garmenzy and colleagues’ (1984) longitudinal study investigated developmental risk factors for psychopathology and the effects of stressful life events on the functional competence of children considered at-risk for psychopathology. The study captured an outlier group of at-risk children who experienced marked deficiencies in functional competence (as measured by social competence and attentional functioning). Surprisingly, the majority of at-risk children in the study displayed adaptive social behavioral patterns and work achievement and presented little to no indication of psychopathology or social incompetence over time (see Garmenzy & Devine, 1984; Nuechterlein, Phipps-Yonas, Driscoll, & Garmezy, 1990 for details). Positive engagements in the classroom and academic achievement were both associated with positive adaptation (i.e., adaptive social behavioral patterns and work achievement) among the at-risk sample; however, the relationship between both of these variables and positive adaptation was moderated by overall intelligence. Moreover, socioeconomic status and social support (family and community) were also related to positive adaptation.

The Kauai study was another longitudinal investigation of resilience, which examined human development from birth to midlife among a cohort of 698 infants born on the Hawaiian island of Kauai in 1955 (Werner & Smith, 1982; 2001). According to Werner and Smith (1977), over one-third of the Kauai study sample experienced marked risk factors or adversity during childhood. Of this at-risk sample, two-thirds developed a learning disability, mental health problem, or behavioral problems by age 18. The remaining one-third developed into competent, well-adapted adults. As children and adolescents, none of these participants developed a learning or behavioral disorder; they all did well in school, managed home and social life adequately, and set realistic educational and job goals. By age 40, all of these individuals were employed, none had a history of legal trouble, and all were financially self-sufficient. Divorce rates were low in this subpopulation of at-risk participants, mortality rates and rates of health problems were significantly lower than their same sex peers, and their educational and vocational accomplishments equaled (even surpassed) those of children who grew up in economically secure and stable home environments (Werner & Smith, 2001).

The Kauai study elucidated the pervasive effects of early childhood relationships on subsequent developmental outcomes, as well as the role of internal locus of control and communication skills in moderating the relationship between risk and poor developmental outcomes (i.e., poor academic achievement). The study continues to explore the impact of biological and psychosocial risk factors, stressful events, and protective factors on human development (Werner & Smith, 2001), with the most recent report from the study highlighting the interactional effect of perinatal stress on the quality of family environment as well as the antecedents and consequences of childhood mental health problems and disabilities. This report links social class and vulnerability, and likelihood of persistence of childhood disorders, with biological and temperamental underpinnings (Werner & Smith, 2001).

Researchers have learned a great deal in the past several decades about protective factors that seem to buffer the impact of severe adversity. The Search Institute has developed lists of developmental assets specific to particular age groups that are associated with positive development. These lists have been integrated into educational programming and parent education programs across the US (Scales & Roehlkepartain, 2003). Each list includes external assets (e.g., support, empowerment, boundaries and expectations, constructive use of time) and internal assets (e.g., commitment to learning, positive values, social competencies, and positive identity), which differ slightly according to age. The developmental assets lists are available in 14 different languages on the Search Institute website (http://www.search-institute.org/developmental-assets/lists). The developmental assets movement calls attention to factors that are associated with positive development among all people, and these assets can be utilized to promote well-being and prevent problems (Scales & Roehlkepartain, 2003).

The notion of resilience evolved largely in a Western context with little consideration for cultural or contextual dimensions of the construct (Liebenberg & Ungar, 2009). Positive adaptation is typically operationalized based on Western assumptions and norms. Protective factors identified in the literature are based on research primarily conducted in Western contexts. A few notable exceptions involve qualitative investigations of resilience factors in several non-Western contexts and point to the need to understand adaptation as influenced by culture and context (Apfel & Simon, 2000; Felsmen, 1989; Klevens & Roca, 1999; Rousseau, Said, Gangé, & Bibeau1998a; Whittaker, Hardy, Lewis, & Buchan, 2005).

International Resilience Project (IRP)

Researchers at RRC conducted the IRP to begin to address the lack of research on resilience among non-Western populations. As previously mentioned, the IRP was a multisite, cross-cultural investigation of resilience among youths living in developing nations or among marginalized populations within developed nations (Ungar & Liebenberg, 2009). The IRP developed and pilot tested the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM), which was later adapted into the RRC-ARM. The IRP concluded the CYRM was a valid measure of resilience, appropriate for use across cultures and contexts.

The IRP concluded neither qualitative nor quantitative methods alone can completely capture resilience. Culture is captured well through qualitative methodology. One can observe and document the tone and tempo of narrative, the environment in which the interview took place, behavioral and interpersonal characteristics that shaped the interview experience. These factors can be easily lost in quantitative data, and often these factors are even controlled for methodologically. Qualitative data can provide honesty to research conclusions and contextualize our understanding of quantitative data. The IRP produced a contextual definition of resilience:

In the context of exposure to significant adversity, whether psychological, environmental, or both, resilience is both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to health-sustaining resources, including opportunities to experience feelings of well-being, and a condition of the individual’s family, community and culture to provide these health resources and experiences in culturally meaningful ways (Ungar, 2008, p. 225).

This definition includes the process of navigating and negotiating for health-sustaining resources. This inclusion highlights the dynamic nature of resilience and distinguishes it from more static explanations, such as those defined by outcome variables (e.g., school success) or culturally independent processes. The term navigation relates to individual capacity (or personal agency) to seek health-sustaining resources, as well as availability of those health-sustaining resources. One can only navigate toward experiences that are available and accessible to them (Ungar, 2008). The term negotiation refers to provision of health-sustaining resources in ways that are meaningful to the individual. In other words, individuals negotiate for resources that members of their culture consider health-enhancing. Resilience as a process can be examined through qualitative data. Processes explain how more static factors work together to promote culturally meaningful pathways toward the experience of health and well-being in the context of adversity (i.e., resilience).

Health and well-being, of course, are also culturally embedded experiences, and resources are contextually bound. Careful consideration should inform selection of outcome markers when conducting cross-cultural investigations. A common outcome marker of resilience across studies among youth, for example, is staying in school. Indeed, staying in school is reflective of positive adaptation in a typical Western context and is likely an appropriate outcome variable with shared meaning within this context. In some non-Western contexts, however, staying in school may not be as important. Working the family farm in order to earn enough income to meet basic needs of the family may be more important than staying in school. Measuring educational attainment in this hypothetical context may lack cultural relevance as a marker of resilience. Identifying culturally valued and contextually relevant markers of resilience is essential to culturally-relevant investigations of resilience.

Four propositions for the study of resilience

The IRP offered four propositions useful to the contextualized study of resilience (Ungar, 2008). Each proposition builds on the other, concluding in the presentation of seven tensions through which resolution (using four common strategies) results in the experience of resilience.

Proposition One states resilience has universally and culturally and/or contextually specific dimensions. Ungar (2008) explains how individuals share a common set of characteristics and processes related to resilience. The IRP produced reliable and valid quantitative data across cultures; but, they were unable to produce a universally valid factor structure.

Proposition Two states various dimensions of resilience exert differing amounts of influence on an individual’s life depending on the culture and context in which resilience is realized. Ungar (2008) explains how understanding the amount of influence a particular aspect of resilience exerts on well-being is difficult to determine, particularly through quantitative methods alone.

For example, comparing mean scores (on a 5-point scale) on the CYRM item ‘Are religious or spiritual beliefs a source of strength for you’ across three different contexts, Sheshatshiu (M = 1.7), Halifax (M = 2.64), and Palestine (M = 4.44), may lead to the conclusion that religious beliefs are of greater importance to Palestinian youth compared to youth in the other two contexts. What is unclear based on quantitative data alone, however, is whether higher endorsement of the item by Palestinian youth represents a greater influence on resilience given Palestinian culture and context, or whether higher endorsement simply reflects cultural relevance, not necessarily influence. Palestinian youth may simply be surrounded in more religious and spiritual expressions of culture leading to greater endorsement of the item. Measuring any aspect of resilience in one context may or may not relate to measurement of the same aspect of resilience in another context (Ungar, 2008).

Proposition Three states that aspects of individuals’ lives that contribute to resilience are related to one another in patterns that reflect individuals’ culture and context (Ungar, 2008). Rather than neatly sorting into individual, relational, communal, and cultural aspects of healthy functioning, aspects of resilience link together thematically in different ways depending on the culture and context in which individuals reside. For example, Ungar and colleagues (2007) hypothesized CYRM items related to self-efficacy would load at the individual level. They found that response patterns on the CYRM linked individual-level self-efficacy, with self-efficacy in relationships, in the community, and in the cultural context (e.g., political efficacy).

Proposition Four states that individuals who successfully resolve the seven tensions (viz., access to material resources, relationships, identity, power and control, cultural adherence, social justice, and cohesion) are those who experience themselves, and are seen by their communities, as resilient. These seven tensions emerged from IRP qualitative data analysis. There is not a prescriptive way in which individuals successfully navigate through these tensions. It is the fit between the attempted solutions and how well the solution resolves the challenges posed by each tension, within the norms of each community (Ungar, 2008). See Table 1 for a summary of the seven tensions described by the IRP.

Table 1

Seven Tensions

| Tension | Explanation |

| Access to Material Resources | Availability of financial, educational, medical and employment Assistance and/or opportunities, as well as access to food, clothing and shelter |

| Relationships | Relationships with significant others, peers and adults within one’s family and community |

| Identity | Personal collective sense of purpose, self-appraisal of strengths and weaknesses, aspirations, beliefs and values, spiritual and religious identification |

| Power and control | Experiences of caring for one’s self and others, the ability to effect change in one’s social and physical environment in order to access health resources |

| Cultural adherence | Adherence to one’s local and/or global cultural practices, values, and beliefs |

| Social justice | Experiences related to finding a meaningful role in community and social equality |

| Cohesion | Balancing one’s personal interests with a sense of responsibility to the greater good; feeling a part of something larger than ones’ self socially and spiritually |

Note. Reprinted from Ungar, 2008, p. 231

Ungar (2008) identified four principles that govern the resolution of the seven tensions. First, individuals can only select from available and accessible health resources. Second, individuals will choose the available health resources that are most likely to influence their health positively (as determined by culture and context). Third, the way individuals relate one aspect of resilience to another will reflect similarities and differences in how individuals behave across cultures. And fourth, relationships between aspects of resilience will be expressed differently within and between populations.

To provide a context through which to consider cultural implications of the present study, an overview of Somali culture is presented next.

Somali Cultural Profile

Somalia is a country located in the northeastern corner of the African continent in a region commonly referred to as the horn of Africa. The country is roughly the size of Texas and has the longest coastline on the African continent. The Indian Ocean is to the east and the Gulf of Aden to the North; the country of Djibouti borders to the north, and Ethiopia and Kenya border to the west and southwest respectively (Putnam & Noor, 1993). The climate of Somalia is very hot and dry, although the higher elevations in the northern part of the country offer cooler temperatures (Putnam & Noor, 1993). This semi-arid to arid environment is conducive to nomadic pastoralism, a form of agriculture practiced by over 50% of the Somali population, in which livestock are herded either continuously or seasonally in search of fresh pastures for grazing. Somali people are also fishermen and seafarers, farmers, and urban businesspeople (Putnam & Noor, 1993).

Culturally, Somali people may be a group for whom Western conceptualizations of mental health treatment are not intuitive (or applicable). According to Schuchman and McDonald (2004), Somali people are traditionally unfamiliar with the concept of mood disorders, such as dysthymia or depression. Mental illness is viewed as a dichotomous construct – either the person is crazy (waali) or not. Somali conceptualizations of mental illness can involve spiritual or metaphysical explanations, and Islam seems to provide an explanatory model for human suffering at the individual and collective level (Koshen, 2007).

Religion

Nearly all Somali people practice Islam, and the religion serves as a unifying force across the country. According Koshen (2007), Islamic teachings suggest all events are of God’s will and are therefore out of individual control. Therefore, some Somali people conceptualized the suffering and social turmoil as God’s punishment for straying from the Islamic path. The way to get back on path is to collectively redirect the society toward Islamic law (Koshen, 2007). The increase in more fundamentalist interpretations of Islam may partially be the result of this conceptualization. Islamic fundamentalists advocate for Shari’ah law (law based on the Quran), which is passed down orally through generations and is thought to preserve basic values in Somali society (Koshen, 2007). Shari’ah law traditionally guided management of communal land and pastures, conflict management and prevention, family law and justice, and diya (the paying of blood money; see Putnam & Noor, 1993 for more details).

Language

A rich oral tradition is an essential component of Somali culture. According to Mire (2007), knowledge of all forms of social life and expression were traditionally transmitted from generation to generation through oral tradition. Poets were the keepers of the clan history, including their relations with other tribes. Poets often acted as a form of mass media, sharing information and public opinion (Mire, 2007). The Somali script was written in 1972 and the Barre administration launched a massive literacy campaign across rural and urban Somalia, purporting to raise the literacy rate to 55% (from 5% prior to the campaign; Putnam & Noor, 1993). Interestingly, Koshen (2007) observed how younger generations of Somali people are more likely to be literate in Somali and English, whereas older generations of Somali people are likely to be illiterate in both Somali and English. Moreover, people born after 1972 are less likely than their older counterparts to speak any other language (e.g., Arabic, Italian, Swahili; Putnam & Noor, 1993).

Social structure

Somali people belong to a patrilineal society, and their clans and subclans identify everyone (Abdullahi, 2001). This fact is reflected in the common Somali question, tol maa tahay, which means, what is your lineage? The clan identity forms the foundation of social structure in Somalia – clan identity defines relationships, rights, and obligations (Koshen, 2007). Illustratively, children are taught to memorize and recite their genealogy backwards along the male bloodline (fathers, grandfather, etc.) until they reach the founding father of the clan, which is often up to twenty generations back (Koshen, 2007).

According to Putnam and Noor (1993), there are two overarching clans in Somalia: Samaale and Sab. Samaale are the majority group and consist of four main subclans: Dir, Isaaq, Hawiye, and Daarood. Each of these subclans is divided into additional subclans. Samaale are primarily of nomadic ancestry and live across east Africa. Sab have two main subclans: Digil and Raxanweyn. Sab live mainly in southern Somalia and mix farming and herding, making them more likely to live a sedentary lifestyle than Samaale (Putnam & Noor, 1993). Clan stability is unpredictable, and changing alliances and temporary coalitions are common.

Family

Five Islamic prescriptions define Somali family structure. First, marriage is a religious duty and social necessity. Second, sex outside of marriage is prohibited. Third, the husband is obligated to provide for his wife. Fourth, the wife must obey her husband. And fifth, family members are obliged to be kind to relatives and express concern for their well-being (Houseknecht & Pankhurst, 2000, as cited in Koshen, 2007).

Somalis tend to value family, and the family serves as a source of support and security during difficult times (Koshen, 2007). It is not unusual for a Somali family to have seven or eight children, and household composition typically involves extended family members and often exceeds ten persons. Extended family includes paternal and maternal relatives and people who are several times removed and belong to another clan (Koshen, 2007). Nurturing Islamic values in children is of primary importance, and children are granted incremental duties in the family along gender lines (Abdullahi, 2001).

Gender roles

Somalia is primarily a male-centered society in that men are responsible for clan and family decision-making, at least publically. Women do, however, play an essential economic role in farming, herding, and business in the city, and men often seek counsel from women regarding important decisions (Putnam & Noor, 1993). Division of labor in pastoral life is clearly defined. Men are responsible for the safety and security of their herd, and they travel long distances scouting for water and fresh pastures on which the herd can graze. Women are responsible for domestic work, caring for the children and elders, loading and unloading camels, raising and taking apart the traditional shelter (awal), and keeping count of the livestock (Koshen, 2007).

Marriage in Somalia was traditionally arranged. Marriages across clans were encouraged as these strengthened alliances across clan groups; however, one of the consequences of the Civil War is that women are more likely to marry within the clan or sub-clan to reduce their chances of falling victim to inter-clan conflicts (Koshen, 2007). After marriage, women maintain their legal rights with their agnatic group (i.e., their father’s clan group). These rights serve to protect her well-being. If a husband were to mistreat his wife and the woman was in distress, for example, her kinsmen are responsible for providing her material assistance, and they may seek compensation from the husband’s clan. Likewise, if the wife were to commit a crime, her kinsmen would be responsible for paying compensation (Koshen, 2007).

Health and health-sustaining resources

According to the United Nations Human Development Report (UNDPR, 2001), the average life expectancy in Somalia was estimated at 47 years old, with women living slightly longer than men. The infant mortality rate and the under-five mortality rate are among the highest in the world (132 and 224/1,000 live births, respectively). At the time of the report, only 28% of people living in Somalia had access to any form of modern health services, and there were only 0.4 doctors per 100,000 persons living in the country (UNDPR, 2001). Little is known about the health and well-being of people living in Somalia.

History of Somali Civil War

The Somali Civil War started roughly in 1991 with the collapse of the Said Barre regime (Abdullahi, 2001). A drought settled over East Africa at about the same time, and food and power fell into the arms of those with guns. Over the course of one year, hundreds of thousands of Somali people died from violence, disease, and famine (Putnam & Noor, 1993). In 2011, the UNHCR reported alarming deterioration with regard to the situation in Somalia yet again. The number of Somali refugees arriving in neighboring Kenya, Ethiopia, and Yemen during the first quarter of 2011 was reportedly double that of the number during the first quarter of 2010 (50,000 from 25,000, respectively). Another drought settled over East Africa in 2011 (said to be the “deadliest in 60 years”), leading to widespread famine and fueling the ongoing political violence. News emerged recently (September, 2012) from Somalia of an elected government now formally recognized by the United Nations. This is the first formally recognized government in Somalia in over 20 years.

Study Aims

Now that an overview of Somali history, culture, and current sociopolitical context has been presented, I will next present a brief discussion of studies on resilience among Somali refugees, leading to a presentation of this dissertation’s study aims. As mentioned previously, only two studies have explicitly examined resilience with Somali refugees, and both were qualitative studies. Rousseau and colleagues (1998a) conducted an ethnographic exploration of resilience with a historically high-risk group of refugees – unaccompanied minors. They analyzed the collective mechanisms of the pastoral society of Northern Somalia that “put the resistance and ability of young refugees to the test” (Rousseau et al., 1998a, p. 161). Using ethnographic data and storytelling, the authors showed how the collective meanings attributed to early separation from family (e.g., learning, positive development) served as a protective factor, buffering the impact of later separation from family due to the Civil War and violence.

In the context of pastoral life in Northern Somalia, children are first assigned their own role in pastoral life around the age of five. The child begins to look after the small animals in and around the camp. Gradually assuming more responsibility, the young men become apprentice camel drivers (dabadonn) at the age of 12. This involves participation in the practice of transhumance (hergeeline) and the experience of lengthy separations from their community and family. During hergeeline, the dabadonn (like his seniors, the geeljirs) must abstain from eating or drinking all day long and wait until all of the camels are milked before feeding himself in the evening. The memories of exhaustion, hunger, and perseverance are firmly implanted in a young man’s early experience. The dabadonn lives with his peer group during the months of separations, as they ensure survival during these months through emotional support and shared experience.

Separation from family in pastoral life is associated with learning and positive development. A boy cannot become a man until he is able to endure the hardship of hergeeline, and gains full acceptance as a man only after he marries. Rousseau and colleagues (1998a) suggest the meaning linked with culturally mandated separation may serve as a protective factor, essentially buffering Somali men from the negative effects of stress later in life. Rousseau and colleagues’ (1998a) qualitative finding offers a contextually bound explanation related to subsequent expressions of resilience (e.g., positive adaptation in the context of forced displacement).

In the second study of resilience among Somali refugees, Whittaker and colleagues (2005) examined the psychological well-being of Somali refugee women living in Northern England. They defined psychological well-being in terms of positive emotional and mental health, life satisfaction, positive affect (happiness), and coping abilities, and they considered the construct (well-being) through social, political, and psychological lenses.

The participants described the importance of moving on, being strong, not dwelling on the past, and coping as essential components of psychological well-being, and they sought support from family, friends, and professional services. However, the women also discussed the need for concealment of mental health problems from others in their community due to stigma associated with mental illness. Refugee populations often report resistance toward engaging in research focused on psychopathology due to culturally embedded stigma related to mental illness (Ingleby, 2005). Whittaker and colleagues (2005) demonstrated how this stigma might play a role in the Somali refugee community as well.

The present study extends the literature on Somali conceptualization of resilience and the work of the IRP by administering the RRC-ARM to a sample of Somali refugees living in the US and exploring dimensions of resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement. A participatory, sequential, mixed-method design was chosen for this study in order to capture both depth and breadth of information about resilience in this context. The research design included three broad phases. During phase one, we conducted interviews with resilient Somali people (n =10) living in the US about experiences of health and well-being in the context of adversity across three distinct contexts (i.e., Somalia, refugee camps, US).

We sought to answer the following research questions during phase one to gain contextual information about resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement:

- How do “resilient” Somali refugees currently living in the US conceptualize resilience?

- What resources contribute to resilience processes and outcomes, health and well-being?

- How does context and culture shape the experience of health and well-being?

These interviews produced rich descriptions of resilience and well-being and formed the backbone for a quantitative investigation (phase three) of resilience. During phase two, we selected study measures for phase three based on findings from phase one. Also, during phase two, we engaged in an iterative process of translation, back-translation, and cultural adaptation of all study measures. During phase three, we administered a quantitative survey of life difficulties (PMLD), well-being (PWI-A), meaning in life (MLQ), and resilience (RRC-ARM) to a sample of Somali refugees (n = 137) living in the US. We sought to answer the following research questions in phase three:

- What kind of factor structure can be established for a measure of resilience among Somali refugees?

- Can enough evidence be produced to support the reliability of the RRC-ARM?

- Can enough evidence be produced to support the construct validity of the RRC-ARM?

- Can enough evidence be produced to support the incremental validity of the RRC-ARM?

Qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed separately and then integrated into a proposed Somali Multilevel and Multidimensional Resilience (SMMR) model.

Chapter 3: Research Design and Methodology

Overarching Study Design

This study employed a participatory, sequential, mixed-method research design to examine resilience in context of Somali culture and forced displacement. Cultural advisors participated during each phase of the study. Mixed-methodology (qualitative and quantitative) allowed for examination of resilience with both depth and breadth (Onwuegbuzi & Leech, 2005). The study involved three broad phases, depicted by Figure 2.

Figure 2. Three-phase research design

Cultural Advisors

As recommended by Ungar and Liebenberg (2009), three cultural advisors oversaw all phases of the project. Most importantly, cultural advisors contributed to the selection of study variables considered culturally relevant and respectful of participant and cultural boundaries. Cultural advisors’ feedback was taken seriously and resulted in several key changes to research design. For example, when this study was originally conceptualized, the key variables of interest were resilience, depression, and anxiety disorders. However, the cultural advisors suggested that measurement of mental disorder might serve as a disincentive to participation in the study. They recommended selection of a positive psychological construct, such as well-being. Thus, the Personal Well-being Index-Adult (PWI-A) was selected as a substitute for measurement of disorder.

Cultural advisors participated in a variety of other ways, including:

- Co-conceptualizing the research project;

- Reviewing key-informant interview protocol and making recommendations for revisions;

- Consultation on key-informant interviews and codebook development;

- Translating and verifying study measures and adapting the study measures, consulting on the survey format;

- Facilitating connections with community organizations who helped facilitate quantitative data collection;

- Interpretation and presentation of research findings.

Meetings with advisors occurred as needed, most typically in the form of telephone conversations, followed by email communications. Somali cultural advisors consisted of one male living in Anchorage, Alaska, and one man and one woman living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. These advisors were chosen because of their own experience overcoming adversity and their understanding of Somali culture, language, and community. Many other Somali community members, as well as many academic and professional consultants, were less formally involved in shaping the project.

Human Subjects Protection

In compliance with Federal Laws and Regulations (42 CFR, Part 2), all aspects of the qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis adhered to strict confidentiality policies and procedures. The University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed all procedures and measures used in this study to ensure the highest ethical standards were respected. All participants were informed of the purpose of the study, what was expected of them if they chose to participate, efforts to ensure confidentiality, and were provided an opportunity to withdraw from the study. If a participant chose to be in the study, he/she was asked to sign informed consent (electronically or in-person depending on the phase of the project as described below) and was reminded that he/she could withdraw from the study at any point without penalty. This study followed all guidelines for the protection of data, including limited access to the data. Data were stored in a locked file room with locked fireproof file cabinets at the University of Alaska Anchorage, and de-identified data were stored in password-protected files on a secure password-protected computer, accessible only by the research team.

Phase One: Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

A qualitative phase was implemented to gather information about resilience in the context of Somali culture and forced displacement. In-person, key-informant interviews with resilient Somali people (i.e., those who have adapted well per the conceptualization of the individual identifying the participant despite exposure to significant adversity) living in Minnesota and Alaska were conducted. Phase one data collection and analysis addressed the following broad research question: How is resilience conceptualized in the context of Somali culture and the refugee experience? More specifically, phase one data collection and analysis sought to answer:

- How do “resilient” Somali refugees currently living in the US conceptualize resilience?

- What resources contribute to resilience, processes and outcomes, health and well-being?

- How does context and culture shape the experience of health and well-being?

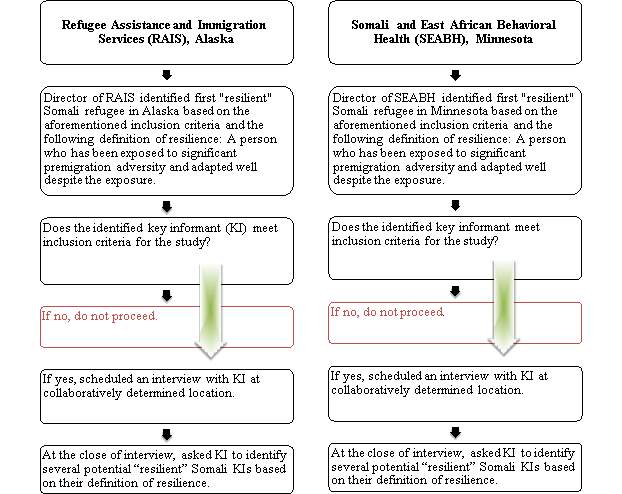

Sampling and recruitment