Cryptocurrency in Organisational Business Use

Info: 7043 words (28 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Colliding Worlds -Cryptocurrency Organisational Business Use

Cryptocurrency has both proven to be more secure in transaction due to encryption transactions and smart contracting by government and financial institutions through achieve widespread adoption as such, regulation standards must be in place to ensure safe and secure transactions (D’Alfonso, et al., 2016). Individuals involved in bribery and corruption will constantly seek to exploit new areas and opportunities to offend and launder their corruption proceeds and evade the scrutiny of law enforcement, and other government or international agencies (Choo, 2015). This study will analyse the pitfalls of acceptance by the Liberian government and its potential use in combatting corruption and bribery. It will question, ‘What are the concerns and factors that cryptocurrency and smart contracts need to overcome to help combat of governmental corruption and enhance transactional transparency?’. The study will be conducted using an interaction analysis. Its goal is to look at the concerns/factors regarding smart contracts and cryptocurrency pitfalls that would require addressing before a beneficial adoption by Liberia for use in combatting country wide corruptive practices and how it relates to widespread acceptance as a secure transactable currency and smart contract permit trusted transactions.

Keywords: Virtual Currency; Blockchain; Digital Currency; Cryptocurrency; Virtual Currency Regulations; Bribery; Corruption;

Statement of Original Authorship

2.2 Prevalence of the Cryptocurrency and Smart Contract Environment

2.3 How the new age transaction network works

2.4 engageMENT in digital financial corruptive practice

2.5 Types of digital financial corruptive practice.

2.6 Concerns of virtual currency in anti-corruptive practice

1.1 Background

Today virtual currency is becoming increasingly common in the use of financial transactions worldwide. Best stated by John Maynard Keynes in 1930, “Money was reached when the State claimed the right to declare what thing should answer as money to the current money-of-account—when it claimed the right not only to enforce the dictionary but also to write the dictionary” (Dowd, Hutchinson, & Kerr, 2012).

Cryptocurrency today can revert to or from fiat currency free from any constraints of law or even conventional morality making it difficult for government to make an important decision whether there is a need to regulate cryptocurrency or not (Dowd, Hutchinson, & Kerr, 2012; Abboushi, 2016). Through the emergence of virtual money, several factors have developed, such as technology; economic law of substitution; a new decentralized payment system all going beyond government control without regulatory permission raising both concern but more so possibilities that can be taken advantage of such as transactional speed, low operational costing, transparency, no geographical boundaries, fraud negation and based on cyber security asymmetric encryption algorithms (Artemov, Arzumanova, Sitnik, & Zenin, 2018; Ivashchenko, 2016).

In under two years cryptocurrency and smart contracting has grown exponentially at a rate of 33.44 times from $17.7 billion to a staggering $592 billion by the end of 2017, an example of this is like Ripple (XRP) that multiplied by 24,000% in price during that year also (Vasin, 2018). For example, as for countries on a fateful day in December 2016, Australia was the first global country to first ever use of a pilot blockchain leger, to facilitate the first ever wheat sale, further leading to promises of reducing settlement of agricultural sales and reduce the number of intermediary actors per transactions from 27 different parties down to 9 parties (Ivashchenko, 2016). This technology pilot has led to a high degree of economical interlocking technology replacing a trusted third party, replacing the already pre-agreement of price for grain, automatic weighing of the grain delivery, verification of the funds via blockchain, and an automatic release of the funds to the farmer (Bacina, 2018).

Furthermore, cryptocurrency and smart contracting has become an acceptable currency for the purchase of food or means of payment in accordance with coinmap.org the heatmapping shows approximately 13 thousand locations across North & South America, Europe, Asia and small groupings in lower Australia (Vasin, 2018; SatoshiLabs, 2018).

1.2 Context

The context will further advance essential understanding of fintech cryptocurrency and smart contracts collision with the current economic environment, because it adds to the ongoing company understanding of current uses amongst government, business and the financial sector.

1.3 Purposes

This purpose of this thesis is to dive into the the potential of cryptocurrency across the transaction network and the potential of for it use to prevent illegal activity and illegitimate use. Due to the instability of cryptocurrency prices, regulators are worried about the implications criminals who are increasingly using cryptocurrencies for activities like fraud and manipulation, tax evasion, hacking, money laundering and funding for terrorist activities. The problem is the permissible context of cryptocurrencies and smart contracts to the extent relevant in connection with financial crime, money laundering and tax evasion to the perspective of how this can be combated via the corresponding technology.

1.4 Thesis Outline

This thesis will outline how cryptocurrency is being used by government, business and the financial sector at the present time and the technology can be applied in the in financial industry to combat illegal activity and illegitimate use.

The outline of the thesis analyse the current uses of cryptocurrency use within government, business and the financial sectors, extending to a high level look at digital financial corruptive practice, prevalence of corruption, governmental concerns of virtual currency in anti-corruptive practice and proposed enforcement technique.

In the field of cryptocurrency there has been numerous amounts of research into its possible usages of cryptocurrency either as a whole, focused on (1) transactions and scripts, (2) consensus and mining, (3) the peer-to-peer communication network, (4) Node Hacker attacks, (5) potential market basis, (6) overlap between hard-money advocacy and Shari’a-compliant finance, and (7) security and efficiency of blockchain protocols (Rizun, 2015). The research problem that has not been explored in-depth is of how the transaction network could possibly explore the use of cryptocurrency in the fight against corruption within governments.

The following literature reviews analyse how cryptocurrency is being used by government, business and the financial sector now, how this blockchain technology can be used to prevent corruptive practice as well as proposed safeguard measures.

2.1 Historical Background

2.2 Prevalence of the Cryptocurrency and Smart Contract Environment

Smart contracts and cryptocurrencies have helped to advance the current economic environment of contract management and fiat currency through blockchain-trust-based smart legal contracts and asymmetric encrypted algorithmic currency proofs (Lansky, 2018; Ryan, 2017).

According to Vasin (2018), Koeppl & Kronick (2018) and Bacina (2018) there is a strong presence of business acceptance of smart contracts and cryptocurrencies in Europe, North America, South America, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan, and other countries which has given rise to the proving and managing trust in e-commerce, commercial transactions and the eliminating expensive third parties in the transaction network. Chen, Xu, Chen, & Lu (2018) go on to state this interlocking technology is part of the fourth industrial revolution as this technology is being applied to area such as education, finance, insurance, judiciary, and commerce due its ability for use as a hash-based Proof-of-Work (PoW) distributed consensus algorithm; proof-of-zero-knowledge consensus algorithm; and asymmetric encrypted algorithmic peer-to-peer transaction network.

In an analysis conducted by Farell (2015) finding that the market capitalisation use of cryptocurrency and smart contracting to be valued at Point of Stake $18,051,579; Hybrid POW/POS $30,975,020; Proof of Work $3,393,062,083; Byzantine Consensus $268,652,002 partaking for some cryptocurrency up to an average of 122,121 transactions a day for example through major retailers like TigerDirect, Overstock.com, and Zanga (DHS, 2014; Chiu & Koeppl, 2017).

According to MyungSan (2018), more than 100 blockchain projects have been created to transform government systems in more than 30 countries from blockchain voting to digital currency system projects along with research into the physical technology possibilities to help transform and modify the fields of engineering and scientific knowledge. For example, according to MyungSan (2018), specific government blockchain projects that are currently taking place are as follows:

- Australia – Australian senators launch parliamentary friends of blockchain group

- Estonia – Development of a blockchain eID (electronic ID management system), E-health (medical information management system) and e-Residency (a first-of-a-kind a transnational digital identity

- The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia – The central banks of the UAE and Saudi Arabia announced the launch of a pilot initiative that two institutions would test a new cryptocurrency for cross-border payments

- United Kingdom (UK) – The government department of Work and Pensions are testing a welfare payment blockchain distribution system and blockchain as a service within their departments

2.3 How the new age transaction network works

In accordance with Letourneau & Whelan (2017) blockchain, or distributed ledger technology (DLT) foreshadows the future of the transition to the new transaction network, due to its ability not to have to rely on intermediaries to broker FX transactions, maintain records, control title transfers, and even charge mark-ups for services rendered.

The blockchain-based cryptocurrency is a decentralized-computer-terminal participant that are linked together through a trust-based smart legal contracts and asymmetric encrypted algorithm that enables direct contracting between buyer and seller without employing intermediaries (Crosby, Nachiappan, Pattanayak, Verma, & Kalyanaraman, 2015; Zheng, Xie, Dai, Wang, & Chen, 2017)

Furthermore, the other side of the blockchain channel is blockchain-based smart contracts according to Alharby and Moorsel (2017) is contained in a distributed database that records all transactions built around executable code that runs on top of the blockchain to facilitate, execute and enforce an agreement between untrusted parties without the involvement of a trusted third party. Allowing for peer-to-peer transactions through a decentralised ledger enables buyer and seller to communicate directly with confidence that the ledger is accurately represented in their chronological dealings without the intermediary costs (Alharby & Moorsel, 2017).

The core concepts behind blockchain-based technology are:

- Transactions: individualized transfers are seen from one subject to another represented as A to B transactions, neither as a physical or software object but rather of incoming and outgoing transactions being tracked from its birth (Gatteschi, Lamberti, Demartini, Pranteda, & Santamaría, 2018).

- Blocks: transactions are grouped into blocks, as a collective reference to all the transactions given over a timeframe and keeping reference to the proceeding block known as the concept of “chaining”, in which these are used to validate on the distributed ledger (Chen, Xu, Chen, & Lu, 2018)

- Nodes: The blocks that are created as reference points to transactions are not stored like conventional transitions in a centralized database but are spread across “nodes” or a network distributed area since a central authority is missing, and decisions on the network are made in accordance with a majority consensus (Gatteschi, Lamberti, Demartini, Pranteda, & Santamaría, 2018);

- Mining: nodes are either passively storing a copy of the blockchain, or actively take part to the maintenance of the blockchain, through a process of “mining” validation via the use of complex computational-intensive mathematical problem limiting the probability success adding a new (malicious) block or modify a previously added block to the chain (Gatteschi, Lamberti, Demartini, Pranteda, & Santamaría, 2018).

- Wallet: A wallet is the credential storage of a complex, unchangeable combination of automatically assigned numbers and letters representing an asymmetric encrypted algorithm created associated addresses, and stored credentials of one or more unique information points on validated transacted, amounts in association of the blockchain (Bacina, 2018; Gatteschi, Lamberti, Demartini, Pranteda, & Santamaría, 2018)

In such, by gaining insight into how blockchain technology works and extended to smart contracting by adding in more variables to the blockchain transaction requirements, there is several capabilities that are presented into how it works across different vectors as described through Gatteschi, Lamberti, Demartini, Pranteda, & Santamaría (2018):

- Government: It would provide an autonomous governance system where it can create transparent citizen voting capabilities or politician programs;

- Finance: transferring money between parties without the relying on traditional banking;

- Education: it would allow for the storage and verification of qualification authenticity to help reduce fraudulent applications as it would store information about when and where the competency was obtained;

- Internet: the use of blockchain would reduce censorships through the exploitation of object-oriented and functionally programmed immutable information that is stored on the chain;

- Commerce: this would allow for goods’ characteristics such as ownership authenticity especially in the arena where there is a potential of counterfeiting or potential for theft; and even

- Internet of Things: this could be achieved by exploiting smart contracts to automatically process data coming from the new areas of robotics and artificial intelligence

2.4 engageMENT in digital financial corruptive practice

An important factor when analysing concerns and factors in governmental adoption is how cryptocurrency and smart contracts can negatively impact digital anti-corruptive practice and who engages in this practice. The first thing that needs to be discussed when analysing this is the simple matter of who engages in digital corruptive practice. Bryans (2014) and Bray (2016) found that when it comes to cryptocurrency digital corruptive practice is the association of an individual for anonymity online with the opportunity to commit illegal acts or make illegal purchases. DHS (2014) also found that predominate results of American senior management engagement in financial corruptive practice increased from 12% in 2009 to 18% in 2011 looking to increase company performance internationally and stock prices. This is further represented through findings of Liberian corruptive practice and use of digital fintech development to secure expected gifts from contractor applicants (Chêne, 2012; Adermu, 2013; Couto de Souza, et al., 2018). This is intriguing as a study conducted by Fanusie & Robinson (2018) over half a million bitcoins moved directly from illicit sources (Darknet Marketplace, Ransomware, Darknet Services, Darknet Vendors, Fraud Activity and even Ponzi Schemes) to conversion services (Bitcoin ATMs, Bitcoin exchange, Crypto-Exchange, Gambling, mixer, multi-service) between the period of 2013 to 2016.

2.5 Types of digital financial corruptive practice.

Researchers have also conducted various studies and literature investigations into the type of financial corruptive practices that have occurred using fiat currency to the transition of more anonymous digital currencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Menero, Zcash etc (Choo, 2015; Lang , 2017; MWR InfoSecurity , 2017).

MWR InfoSecurity (2017) conducted a study, which concluded that in recent times the use of cryptocurrency due to the changes in e-payment systems is causing a paradigm shift in cyber-criminal underground markets, and use in cyber-extortion attacks against organisations and governments. Furthermore, it has been identified through sources significant levels of corruption have increased in peer to peer anomoumous digital currency payments from illegal sources or for illegal activities (Mauro, et al., 2017; Giungato, et al., 2017; MWR InfoSecurity , 2017; He, et al., 2016). The International Monetary Fund (He, et al., 2016) found that cryptocurrency or virtual currencies can be used to conceal and disguise illicit origin or sanctioned destination of funds, thus helping to facilitate potential money laundering, and even the evasion of sanctions.

These findings appear to remain true to governmental findings where they found that virtual currency is also used as a vehicle for activities terrorist financing, or even tax evasion through the use of decentralized virtual currency schemes where law enforcement may not be able to investigate due to regulatory catch-up (Choo, 2015; He, et al., 2016).

2.6 Concerns of virtual currency in anti-corruptive practice

The first part of this literature review focused on the prevalence of cryptocurrency within government, business and the financial sector followed by corruptive overview and the types of digital financial corruptive practice but will now focus on the concerns of government regarding the acceptance of virtual currency as a beneficial adoption. While there are a high number of cryptocurrencies with such currencies as Bitcoin averaging 122,121 transactions a day this gives way to serval barriers such as infrastructure, volatility, taxation, credit card, consumer understanding, and consumer protection (DHS, 2014; Chiu & Koeppl, 2017). As such DHS (2014) has outlined that due to the evolving crypto industry there is still a long way to go before entering mainstream usage with these regulatory and governmental concerns including:

- Infrastructure – Virtual currencies are based on a sta ndard computer code that traverses several worldwide servers around the world for regulating the creation of each currency/coin/blockchain, along with peer-to-peer transactions using a decentralised distributed leger (DHS, 2014; Fico, 2016). In infrastructure such as Bitcoin a staggering amount between $20 million and $580 million per day in transactions during the first nine months of 2014 equating to roughly 2,400 per second on its network as this rises the network infrastructure sustainability and scalability will need to surpass its current capacity to banking level commercial viabilities (DHS, 2014; European Central Bank, 2015)

- Taxation – Taxation departments around the world have issued guidance’s surrounding the use of cryptocurrency, how it should be considered a property for tax purposes implying that holders track and report the price of every good and service acquired and paid for using this form of currency (DHS, 2014; Dostov & Shust, 2014). This creates a liability for all cryptocurrency users, investors and even businesses as they are liable to pay tax on capital gains, as such this regulation may introduce a barrier of mainstream day to day adoption by end-users (DHS, 2014; Lee & Chuen, 2015)

- – The issue with virtual currency is that it is a representation of a commodity with a fixed supply with no intrinsic value as such remains highly volatile which has seen vast fluctuations after high-profile exchange bankruptcies, numerous occurrences of hacking and theft, and even regulatory uncertainty announcements (DHS, 2014).

- Consumer Understanding – Due to the loss of trust in the banking sector in recent times and the fear of capital loss, interest rates and economic uncertainties. Cryptocurrency is starting to be embraced more hastily without complete understanding of security threats, system collapses, value fluctuation, and even the real-life implications of crypto-exchange bankruptcy and closures (DHS, 2014; Ritcher, et al., 2015)

- Credit Card – Credit cards are a form of digital credit that is familiar to consumers and essential for merchants, as there are three main reasons that differ mainstream to the new cryptocurrency these are in accordance with DHS (2014) findings of:

- Customers being able to use debt to pay for items by which cryptocurrency acts like a debit card;

- Credit card technology provide a high level of sophisticated fraud prevention and recovery; and

- There is an added element of reward or discount capabilities attached to each card subscription.

However, the barrier that will be required to be overcome for end user acceptance and governmental regulatory acceptance is ‘Customer protection’ as current banking environments have layers of robust security controls and mechanisms, inclusive of regulatory backing, regulatory auditing and financial insurance backing (Abbasi & Weigand, 2017; DHS, 2014). However, there is high incidence of security breaches at cryptocurrency exchanges that are not properly regulated either nationally or globally hamper consumer confidence, this in turn has seen a non-acceptance and non-insurability by programs such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund that provide a level of protection secondary of banking debt (DHS, 2014; Dubauskas, 2012).

The focused on the prevalence of corruption and the types of digital financial corruptive practice, can be seen through the extending circumstances above such as tax evasion, infrastructure usage and even in consumer protection laws or regulations, along with the currency retainment of anonymity for peer-to-peer transactions. The security of cryptocurrency is a hotly debated topic with its ability also to easily be accessed and the data compromised at the peer end or exchange node points in which at times an individual can purchase hacking tools or simply purchase a service for attack (Bray, 2016). Due to its premature nature the cybercrime capabilities of cryptocurrency usage in financial crimes leaves it capable of being exploited as a strategy for conditional anonymity thus leading governments such as Liberia with a double-edged sword of having a secure transactable method that can be tracked if the technology is imposed to replace of current regulatory banking, but several issues as described that would require consideration prior.

2.7 anti-corruptive INTELLIGENCE MODEL

In accordance with Budhram (2015), Lee and Chuen (2015) an approach that has been proposed for adoption to help fight crypto-illicit transactability is the “intelligence-led Anti-Money Laundering (AML)/Counter Terrorism-Financing(CTF) Directive policing model” by which criminal intelligence (e.g., of organized crime and corruption activities) and data analysis are used to provide valuable input to a decision making framework in an effort to reduce, disrupt, and prevent crime through strategies and management.

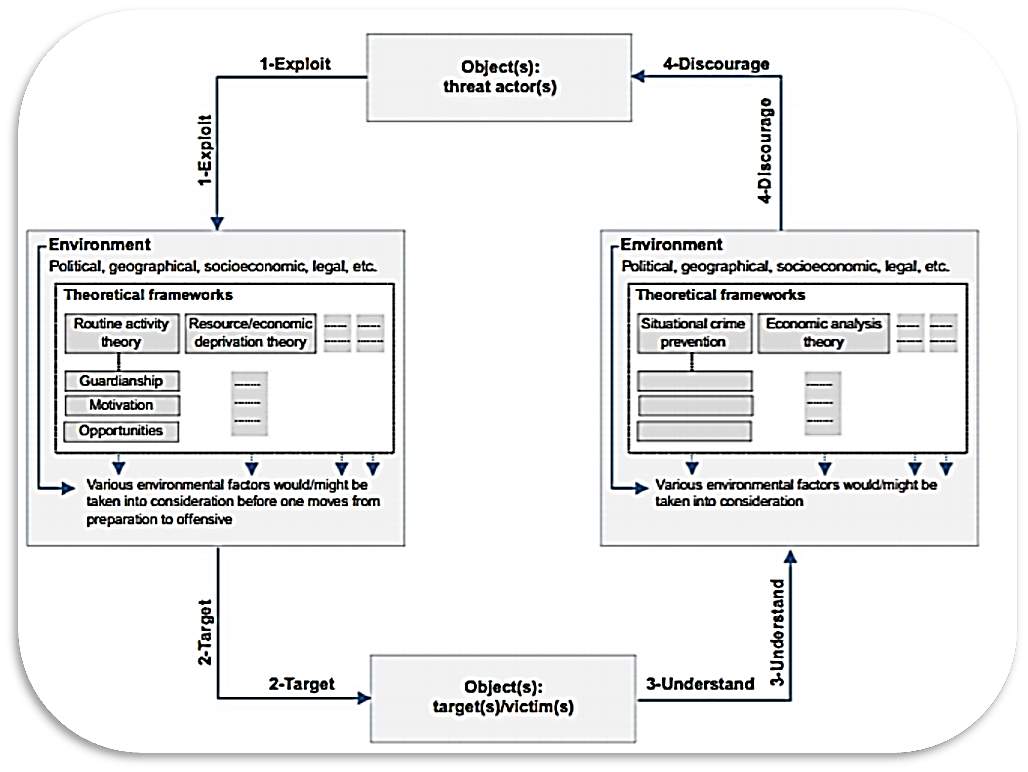

Figure 1: Intelligence-led AML/CTF strategy

The intelligence-led AML/CTF strategy is a conceptual framework that has been adapted to study and understand complex threat landscape faced by governments, government agencies (e.g., financial intelligence units and AML/CTF regulator cewqs), and cryptocurrency and virtual currency providers and intermediaries (Budhram, 2015).

In order understand these complex threat landscapes, an understanding of the interplay between the objects (e.g. threat actors in way of this thesis would be represented as corrupted individuals seeking to exploit virtual/crypto-currencies to launder corruption proceeds and victims such as government agencies); environmental factors (e.g. technologies, political, geographic, socioeconomic, legal and regulatory, and cultural); environment; and interplay factors further shaped due to integrated governance and risk management strategy evolution as circumstance requires (Budhram, 2015).

The ILP AML/CTF strategy is to ensure the effective use of up-to-date intelligence combined with top-down/bottom-up built information-organising process risk assessment and risk management (Budhram, 2015; Choo & Lui, 2014). As such this model heavily requires criminal intelligence analysis to actively interpret the criminal environment through (Lee & Chuen, 2015; Choo & Lui, 2014) :

- providing situational awareness;

- making careful predictions about future trends for ICT, regarding new payment methods including cryptocurrencies and virtual currencies;

- making careful predictions regarding the scaling threat landscape at both localized and international levels;

- making careful predictions regarding the impact of corruption;

- making careful predictions regarding the potential for ICT exploitation to launder corruptive proceeds on the society; and

- assurance that appropriate controls (e.g. resources and investment) are in place to ensure that criminal exploitation is minimized.

2.8 Summary and Implications

Summarise the literature review and discuss the implications from the literature for your study – the theoretical framework for your study. Here you can make an explicit statement of the hypotheses, propositions or research questions and how they are derived from existing theory and literature. Establish from the literature (or gap in the literature) the need for this study and the likelihood of obtaining meaningful, relevant, and significant results. Outline any conceptual or substantive assumptions, the rationale and the theoretical framework for the study. Explain the relationships among variables or comparisons, and issues to be considered. This section should demonstrate the contribution of the research to the field and be stated in a way that leads to the methodology.

This chapter of the thesis should outline the design and methodology of your research. The basis for the choice of research method should be whether it will help you answer your research question(s).

Give an overview of what is to be included in this chapter. For example:

This chapter describes the design adopted by this research to achieve the aims and objectives stated in section 1.3 of Chapter 1 [if you wish, you can restate those objectives]. Section 3.1 discusses the methodology [to be] used in the study, the stages by which the methodology was [will be] implemented, and the research design; section 3.2 details the participants in the study; section 3.3 lists all the instruments [to be] used in the study and justifies their use; section 3.4 outlines the procedure [to be] used and the timeline for completion of each stage of the study; section 3.5 discusses how the data was [will be] analysed; finally, section 3.6 discusses the ethical considerations of the research and its [potential] problems and limitations.

3.1 Methodology and Research Design

3.1.1 Methodology

Discuss the methodology [to be] used in your study (e.g., experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, casual-comparative, survey, discourse, case study, analysis, action research). If using stages, outline them here. The methods used must link explicitly to the research question and must be suited to the nature of the question. Discuss any methodological assumptions.

3.1.2 Research Design

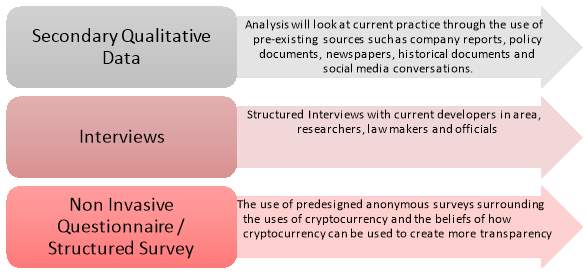

The nature of this research is to identify and explore the relationships between cryptocurrency what is its current usage in the transaction network and the potential it has to lead to better practice helping to negate corruptive practice. Therefore, a mixture of methods both qualitative and quantitative are used in the collection methods of Interviews, Surveys and Secondary Qualitative Data

3.2 Participants

The sample size of this will look at a controlled group of 15 Interviews and 150 Surveys as this will help draw some conclusions due to them known as “sample population”. This allows for the study data obtained to be analyzed and conclusions to be drawn.

Participants have been chosen based on their proximity to the monetary policy, digital forensic accounting and researchers within the academia, and practical fields of cryptocurrency.

Contact will be made with participants via personalised invitation and surveys will be developed through the approach of accounting firms with permission being sort to contact individuals within government departments such as the reserve bank or gateway engineers from mastercard here in brisbane.

3.3 Instruments

List and briefly describe all the instruments (e.g., tests, measures, surveys, observations, interviews, questionnaires, artefacts) [to be] used in your study for data collection and discuss their theoretical underpinnings, that is, justify why you used [will be using] these instruments. So that the line of argument is not broken, it is useful to place copies of instruments in Appendices to which this section can refer.

3.4 Procedure and Timeline

Outline the procedure across and within the techniques [to be] used in your study for collecting and recording data. This could include how, when (in what order) and where the instruments were [will be] administered (for example, field, classroom or laboratory procedures, instructions to participants or distribution of materials) and how the data was [will be] recorded. Include the rationale for the procedures used. If the study was [is to be] done in stages, give a timeline for the completion of each stage.

3.5 Analysis

Discuss

3.6 Ethics and Limitations

[Extra page inserted to ensure correct even-page footer for this section. Delete this when chapter is at least 2 pages long.]

Chapter 5 contains a full discussion, interpretation and evaluation of the results with reference to the literature. This chapter can also include theory building.

As with the previous chapters, include a paragraph at the beginning summarising the structure of the chapter. Organise the chapter in terms of the objectives of the study and/or the theoretical framework. For each objective, discuss the results with reference to the literature, for example, the similarities/differences to the findings in the literature review. Develop theory or models from this comparison and evaluation.

It can be useful to check your literature and try to find a place for as much of the literature as you can. If you find that a section of your literature can not be used in this chapter, it may be useful to consider the pertinence of this literature and reduce the space in the literature chapter given to it.

Thus, your research outcomes are tied together in relation to the theory, review of the literature, and rationale.

[Extra page inserted to ensure correct even-page footer for this section. Delete this when chapter is at least 2 pages long.]

This chapter contains conclusions, limitations, and recommendations – so what is the theory? Where to from here? What are the practical implications? Discussion of where the study may be extended.

Again, the chapter should begin with a summary paragraph of the chapter structure. The opening section(s) of the chapter should be a summary of everything covered so far. Follow this with your conclusions. This is the “so what” of the findings – often the hypothesis/research question(s) restated as inferences with some degree of definitive commitment and generalisability, and the raising of new and pertinent questions for future research. You could include a final model of the theory.

It can be useful to use the purposes from Chapter 1 as an organising structure for this chapter. The chapter should also include a discussion of any limitations of the research and should end with your final recommendations – practical suggestions for implementation of the findings/outcomes or for additional research.

[Extra page inserted to ensure correct even-page footer for this section. Delete this when chapter is at least 2 pages long.]

- Abbasi, T., & Weigand, H. (2017). The Impact of Digital Financial Services on Firm’s Performance:a Literature Review. arXiv, 1-15.

- Abboushi, S. (2016). Global Virtual Currency – Brief Overview. Competition Forum; Indiana, 14(2), 230-236.

- Adermu, W. A. (2013). Eradicating Corruption in Public Office in Nigeria. Interpersona, 7(2), 311–322.

- Artemov, N. M., Arzumanova, L. L., Sitnik, A. A., & Zenin, S. S. (2018). Regulation and Control of Virtual Currency: to be or not to be. Journal of Advanced Research in Law and Economics, 1428-1435.

- Bray, J. D. (2016). Anonymity, Cybercrime, and the Connection to Cryptocurrency. Richmond, USA: Eastern Kentucky University.

- Chiu, J., & Koeppl, T. (2017). The Economics of Cryptocurrencies – Bitcoin and Beyond. Bank of Canada.

- Choo, K.-K. R. (2015). Chapter 15 – Cryptocurrency and Virtual Currency: Corruption and Money Laundering/Terrorism Financing Risks? In D. Lee, & K. Chuen, Handbook of Digital Currency (pp. 283-307). Adelaide, South Australia, Australia: University of South Australia. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802117-0.00015-1

- D’Alfonso, A., Langer, P., & Vandelis, Z. (2016). The Future of Cryptocurrency. Toronto, Canada: Ryerson University.

- DHS. (2014). Risks and threats of cryptocurrencies . Falls Church, USA: Department of Homeland Security.

- Dostov, V., & Shust, P. (2014). Cryptocurrencies: an unconventional challenge to the AML/CFT regulators? Journal of Financial Crime, 21(3), 249-263.

- Dowd, K., Hutchinson, M., & Kerr, G. (2012). The Coming Fiat Money Cataclysm. Cato Journal, 32(2), 363-388.

- Dubauskas, G. (2012). SUSTAINABLE GROWTH OF THE FINANCIAL SECTOR: THE CASE OF CREDIT UNIONS. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 1(3), 159-166.

- European Central Bank. (2015). Virtual currency schemes – a further analysis. Frankfurt: European Central Bank. Retrieved from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/virtualcurrencyschemesen.pdf

- Fico, P. (2016). Virtual currencies and blockchains: potential impacts on financial market infrastructures and on corporate ownership. Melourne Business School. Melbourne, Australia: The University of Melbourne. Retrieved from https://mbs.edu/getattachment/fircg/FIRCG-2016/Papers/7-Paola-Fico_-virtual-currency-blockchain-mb.pdf

- Giungato, P., Rana, R., Tarabella, A., & Tricase, C. (2017). Current Trends in Sustainability of Bitcoins and Related Blockchain Technology. Sustainability, 1-11.

- He, D., Habermeier, K., Leckow, R., Haksar, V., Almeida, Y., Kashima, M., . . . Verdugo-Yepes, C. (2016). Virtual Currencies and Beyond: Initial Considerations. Monetary and Capital Markets, Legal, and Strategy and Policy Review Departments. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2016/sdn1603.pdf

- Lang , B. (2017). Engaging China in the fight against transnational bribery: “Operation Skynet” as a new opportunity for OECD countries. OECD Global Anti-Corruption & Integrity Forum (pp. 1-18). Paris, France: OECD.

- Lee, D., & Chuen, K. (2015). Handbook of Digital Currency: Bitcoin, Innovation, Financial Instruments. Kidlington, UK: Elevier Ltd.

- Mauro, C., Sandeep, K., Chhagan, L., & Sushmita, R. (2017). A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues of Bitcoin. arXiv, 1-36.

- MWR InfoSecurity . (2017). Linking Factors between Cryptocurrencies, Crime and Enterprise Cyber-Attack. Basingstoke, United Kingdom: MWR InfoSecurity.

- Okereke, G. O. (2013). Crime and punishment in Liberia. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 63-74.

- Ritcher, C., Kraus, S., & Bouncken, R. (2015). Virtual Currencies Like Bitcoin As A Paradigm Shift In The Field Of Transactions. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 14(4), 575-586.

[Extra page inserted to ensure correct even-page footer for this section. Delete this when bibliography is at least 2 pages long.]

Start each appendix on a new page. Place appendices in the same order as they are referred to in the body of the thesis. That is, the first appendix referred to should be Appendix A, the second appendix referred to should be Appendix B, and so on. Appendix formatting can be different to the main document. Refer to Thesis PAM for information about appendix figures and tables.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Cryptocurrency"

Cryptocurrency is digital currency that can be used to pay for goods and services, using blockchain technology to ensure secure transactions. Bitcoin is almost certainly the most commonly known Cryptocurrency, though others such as Dogecoin, Ethereum and more are now seeing increased popularity.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: