Modern Day Slavery in the UK and Anti-Modern Slavery Measures

Info: 17227 words (69 pages) Dissertation

Published: 28th Oct 2021

Tagged: Human RightsHuman Rights Law

To what extent does slavery still exist in the 21st Century United Kingdom, what is being done and how effective are the anti-modern slavery measures currently enforced by the government?

Table of Contents

Introduction

Section 1

Key terminology

Origins and background of slavery in Britain

Definition and forms of modern slavery

Modern Slavery in the United Kingdom

Human Trafficking

How is human trafficking able to take place?

Case Study

Forced Marriage

Section 2

What is being done to combat modern slavery in the 21st Century United Kingdom by the government?

Section 3

How effective are anti-modern Slavery efforts in the 21st Century United Kingdom?

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

This project will first investigate the extent to which slavery still exists in the 21st Century United Kingdom and in what forms, despite its abolition in 1833. The project findings will then be used to examine the efforts being made by the government of the United Kingdom to tackle slavery and to make a critical evaluation of how effective they have been to date. The project also intends to discuss the United Kingdom’s historic links to and involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, with a focus on Britain, and the process of the abolition of slavery within Britain. Predominantly, this project will look at the definition and various practices of modern slavery, those which are potentially taking place in the United Kingdom and the reasons as to why they are able to occur.

Slavery is a concealed yet paramount and archaic abuse of human rights that strikingly still exists in the 21st Century, however, it is coming increasingly to light. Through this project, it is intended to develop an awareness of slavery and the depth of the government’s response by discussing the potential presence of modern slavery in the United Kingdom. The scope of research relating to modern slavery covered in this essay will predominantly be regarding the practices of human trafficking, which manifests itself into various forms of exploitation, forced marriage, their definitions and the legislation regarding them. Chattel slavery will also be researched and explained when discussing Britain’s historic involvement in the slave trade. In this project, the government’s response to modern slavery is researched and evaluated and potential methods for their enhancement are also proposed. Discussion of how improvements could be enforced are beyond the scope of this research project.

Section 1

Key terminology

I have chosen to include definitions of the terms used in the title to ensure continuous clarity of expression of what is being asked in the question and what is covered in this project.

Slavery – There are a broad range of definitions for the term slavery and no universal one term, I have chosen to use two definitions, one from the Oxford English Dictionary and the other from the Slavery Convention of 1926.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary slavery is defined as “The condition of a slave; the fact of being a slave; servitude; bondage”.[1]

In the Slavery Convention of 1926 slavery is defined as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised, and “slave” means a person in such condition or status”.[2]

Slave – “One who is the property of, and entirely subject to, another person, whether by capture, purchase, or birth; a servant completely divested of freedom and personal rights”.[3]

The verb “exist” in this project refers to slavery being a reality in the 21st Century United Kingdom.

Origins and background of slavery in Britain

Prior to the 1066 Norman conquest, chattel slavery, in which slaves are the personal property of their masters and can be bought and sold,[4] had existed in England.[5] The slave trade, however, was abolished with the arrival of William the Conqueror.[6] Later, in 1102 “at the Council of Westminster, the Church had outlawed slavery”.[7]Britain’s involvement, however, in the lucrative yet morally contested industry of slavery was reignited by naval commander John Hawkins who conducted a series of three main voyages between 1562 and 1567.[8] During these he kidnapped Africans from the West Coast of Africa and sold them as slaves in the West Indies.[9] Hawkins was cousin to Sir Francis Drake, an English Sea Captain, alongside whom he is thought to have enslaved between approximately “1200 to 14000”[10] Africans.[11] Although Hawkins’ final voyage in 1567 ended disastrously[12] he had rekindled an industry in Britain which lasted a further “250 years”.[13]

Before the endeavours of John Hawkins, the interests of the British primarily lay in the purchasing and trading of African produce.[14] The British, however, became embroiled with the trading of slaves when sugarcane was introduced to Barbados by the Dutch in the 1640’s.[15] Sugarcane production required high numbers of labourers and the Dutch had initially supplied Barbadian farmers with Africans,[16] introducing “plantation slavery”[17]and indentured convicts and servants were supplied by the British.[18] As sugar became a commodity[19] and “Barbados rapidly converted from an English style of agriculture to a few landowners who grew sugarcane and monopolized most of the land”[20] such labour became inefficient regarding the planters’ needs.[21] The British became aware of the abundance of slave labour which the Dutch could supply and followed suit.[22] From then on, the British were involved in the infamous triangular slave trade through which they travelled to Africa and sold manufactured goods to traders for people whom they then supplied to the colonies in exchange for produce.[23] Britain alongside Portugal is reported to be responsible for the transportation of approximately 70% of Africans to the Americas during the slave trade.[24] The three most paramount ports in Britain to which slave trading was solely restricted to in the 1799 Slave Trade Act were in London, Bristol and Liverpool.[25] Britain was also involved in the slave trade through the East India Company which was implicated in the East African slave trade and traded goods with the intentions to acquire slaves from West Africa for its settlements in South and East Africa, India and Asia.[26]

Although Britain’s most prominent involvement in historic slavery was through the trading of slaves, slavery was also present within Britain when Africans were transported to the country along with imperial goods to work in aristocratic households.[27] Once sold into domestic servitude they worked often as butlers or attendants but their main purpose was to provide an image of exoticism, symbolising yet another luxury imperial good from a faraway continent.[28]

Britain’s involvement in historic chattel slavery was arguably abolished in three paramount stages, the first being in the Somerset v Stewart case of 1772[29] in which The National Archives state “a slave’s liberty and status as property”[30] was fought over. The slave in question was James Somerset an enslaved African who was bought by customs officer Charles Stewart in Boston.[31] On his return to England in 1769, Stewart brought Somerset with him, however, Somerset escaped in 1771 but was recaptured in November and put on a ship bound for Jamaica.[32] Granville Sharp, leading abolitionist, among others applied for a writ of Habeas Corpus to the Court of King’s Bench.[33] Habeas Corpus is, according to Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary, “a prerogative writ used to challenge the detention of a person either in official custody or private hands. [In the 21st Century] Under CPR Sch. 1, RSC Ord. 54, application for the writ is made to the divisional court of the Queen’s Bench, or during vacation to any High Court judge. If the court is satisfied that the detention is prima facie unlawful the custodian is ordered to appear to justify it and if he cannot do so the person is released”.[34] The Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, William Murray 1st Earl of Mansfield, granted the writ and ordered Somerset to be brought before the court for a hearing[35]. During the case “Somerset’s legal team argued that although slavery was tolerated in the colonies, the Court of King’s Bench was bound to apply the law of England,”[36] consequently, it was implied that slavery was unlawful in England as it was unrecognised in the law of England or by any passed by Parliament.[37] Lord Mansfield gave his judgement on the 22nd June 1772 which was reported by the English lawyer Capel Lofft[38] quoted in the article Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World in The University of Chicago Law Review journal by Professor Emeritus of History and Law William M. Wiecek. Mansfield reportedly said “the state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political; but only positive law…It’s so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged”.[39] Somerset was freed and although this case did not end slavery in Britain it set an important precedent as Lord Mansfield’s judgement stated that no slave could be unwillingly removed from Britain and sold into slavery.[40] The article in The University of Chicago Law Review journal, which is regarded as “among the most influential journals in the field”[41], also states that the ruling on the case “was a significant judicial expansion of the scope of habeas corpus and a benchmark in the development of the law of personal liberty”.[42] This highlights just how prominent a case Somerset vs. Stewart was in the process of abolishing slavery in Britain.

The next stage in the removal of Britain’s involvement in slavery was the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act which was passed on the 1st May 1807[43] and stated “all manner of dealing and reading in the purchase, sale, barter, or transfer of slaves or of persons intending to be sold, transferred, used, or dealt with as slaves, practiced or carried in, at, or from any part of the coast or countries of Africa shall be abolished, prohibited and declared to be unlawful”.[44] This act ended the British slave trade and its key provisions were that “any ships found to be involved in the slave trade were liable to be seized and condemned”[45], their masters and owners fined £100 per slave and their goods confiscated and handed over to the Crown.[46]

Slavery in the British colonies, however, was not abolished until 1833 in the Slavery Abolition Act which received Royal Assent on 28th August 1833 and took effect on 1st August 1834.[47] “The Slavery Abolition Act did not explicitly refer to British North America. Its aim was rather to dismantle the large-scale plantation slavery that existed in Britain’s tropical colonies, where the enslaved population was usually larger than that of the white colonists. Enslaved Africans in British North America were relatively isolated and far smaller in number”.[48] From this point onward historic chattel slavery was abolished in Britain and it’s “tropical colonies”.[49]

In regard to the question posed in the title, the phrase “still exist” refers to slavery occurring after the abolition of Britain’s involvement in chattel slavery, as explained above, and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. It also refers to after the passing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) following the Second World War and the Supplementary Convention of 1956. The UDHR was announced by the United Nations General Assembly on 10th December 1948 in Paris.[50] The document is “a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected…”.[51] The title of this project refers specifically to slavery occurring in 21st Century Britain after these acts and following Article Four of the UDHR which states “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms”.[52] According to the Talking Points series Slavery Today issue, slavery is also a violation of the fundamental rights “summed up by Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: ‘Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.’ Slavery violates these rights because it deprives people of life, liberty and security”.[53] The phrase “in all their forms”[54] taken from the UDHR is especially important regarding this project as it is in “forms”[55] other than the historical chattel slavery which the Supplementary Convention endeavours to eliminate[56] and this project seeks to uncover whether they continually exist after this and are being practised in Britain.

Definition and forms of modern slavery

Anti-Slavery International, which was established in 1839 and claims to be ” the world’s oldest international human rights organisation and works to eliminate all forms of slavery around the world, “[57] define modern slavery as “exploitative labour that places one person in the control of another… However, if a person is forced to carry out work for which they didn’t offer themselves voluntarily, and they are not free to leave, it is a case of slavery”.[58] The types of slavery that can be categorised under modern slavery go beyond that of “traditional” chattel slavery. “Traditional slavery”[59] is defined by Human Trafficking (Global Issues) as “ownership of other human beings, so that they are treated as property that can be bought, sold, inherited or given to others…a slave is under the total control of their owner and is expected to work without payment”.[60] The Modern Slavery Act 2015 (MSA 2015), the key primary source regarding slavery in 21st Century Britain, passed by the UK Parliament is “An Act to make provision about slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labour and about human trafficking, including provision for the protection of victims; to make provision for an Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner; and for connected purposes”.[61] The MSA 2015 and Anti-Slavery International both acknowledge the forms of “exploitative labour” [62] most commonly synonymised with modern slavery as the following:

- “Slavery, servitude and forced or controlled labour”[63]

- Human Trafficking in which

“A person commits an offence if the person arranges or facilitates the travel of another person (“V”) with a view to V being exploited”.[64]

According to Interpol, the largest international police organisation in the world, trafficking for forced labour, sexual exploitation and the harvesting of organs, cells and tissues are the three main purposes of human trafficking.[65]

Other forms of modern slavery acknowledged by Anti-Slavery International are:

- Bonded Labour which is defined as demanding labour from a person to repay their debts. The person is then coerced into working for minimal or no pay and the value of their labour becomes greater than that of the original debt. Debts can be passed onto next generations[66]

- Descent Based Slavery which is most commonly evident in hierarchical societies and occurs when people are born into a sect of society deemed to be in slavery. This is like chattel slavery in that the people subject to it can be inherited by so-called “masters”,[67] treated like property and as soon as they are born they can be automatically dehumanised and deemed property[68]

- Slavery in global supply chains in which forced labour is used at varying stages in large supply chains[69]

- Child and forced marriage – child marriage can be deemed slavery if the child has not given their informed consent, is under control in the marriage or cannot realistically leave the marriage[70]

These are the forms of slavery publicised by a high profile, global anti-slavery organisation and identified by the MSA 2015 and those which this project will investigate to determine the existence and extent of slavery in the 21st Century United Kingdom.

Modern Slavery in the United Kingdom

To the majority of residents in the United Kingdom, slavery is a thing of the past, an archaic 18th-century shadow looming over the UK’s history and its abolition is generally perceived to have been absolute. The striking reality is, however, that there are estimated to be “more slaves today than ever before in human history– even more than the transatlantic slave trade”.[71] It is estimated that there are approximately 45 million people living in modern slavery worldwide[72] and according to the findings of The Global Slavery Index 2016 (TGSI) out of a population of 64,856,000, 11,700 people are estimated to be living in modern slavery in the UK. The Global Slavery Index is “the world’s first all-encompassing global estimate of slavery with country by country data”[73] produced by the Walk Free Foundation which is an “initiative to end modern slavery”.[74] These findings by TGSI represent approximately 0.02% of the UK population who are living in modern slavery[75], which according to TGSI vulnerability to modern slavery rank, the UK scored 26.79 out of 100.[76] Furthermore, according to The Global Slavery Index’s prevalence of modern slavery rank, the UK is 52 out of 167 countries worldwide regarding the occurrence of modern slavery within the country.[77]These findings from external sources themselves show that slavery does still exist in the 21st Century United Kingdom. The Walk Free Foundation defines modern slavery as “situations where one person has taken away another person’s freedom – their freedom to control their body, their freedom to choose to refuse certain work or to stop working- so that they can be exploited. Freedom is taken away by threats, violence, coercion, abuse of power and deception. The net result is that a person cannot refuse or leave the situation”.[78] Through the course of this project as definitions of modern slavery can differ I have chosen to use both this definition and that provided by the Anti -Slavery International website when referring to modern slavery.

Modern Slavery is a hidden crime, as both the practice of it and its victims are concealed even though we, as residents of the UK, may both engage with victims and in such practices as part of our everyday lives. Through my research of servitude based practices exercised in the UK I have found that slavery is taking place in the 21st Century UK and arguably the two most prevalent forms, that have been made aware to the authorities, of modern slavery taking place in the UK, are human trafficking and forced marriage.

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking as defined earlier in this project by the MSA 2015 is when “A person commits an offence if the person arranges or facilitates the travel of another person (“V”) with a view to V being exploited”.[79] During the course of this project, the research that has taken place and statistics gathered regarding the prevalence of human trafficking in the UK have been through the National Crime Agency (NCA), particularly through the National Referral Mechanism Statistics – End of Year Summary 2015 PDF.

The National Crime Agency is a national law enforcement and policing agency which works alongside the police and other organisations across the UK[80] and whose aim is “to protect the public from the most serious threats by disrupting and bringing to justice those serious and organised criminals who present the highest risk to the UK”.[81] Within the NCA exists the Organised Crime Command(OCC) and within the OCC exists the Modern Slavery Human Trafficking Unit (MSHTU) whose aim it is to “combat modern slavery crimes”.[82] The MSHTU produce the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) which is a “framework for identifying victims of human trafficking or modern slavery and ensuring they receive the appropriate support”.[83] This is used by the MSHTU to gather information about victims of trafficking or modern slavery to produce a clearer image of the breadth of the existence of human trafficking and modern slavery in the UK.[84] As the UK is still currently a member of the European Council, at the time of writing this project, and therefore subsequently a member of the Council of European Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings Treaty it is part of its obligations to produce the NRM and ensure that it’s central focus is the location and identification[85] of “potential victims of trafficking”.[86] The identification of potential victims is important as their existence suggests the extent of vulnerability and the risk of people in the 21st Century UK being involved in modern slavery and therefore importantly contributes to an understanding of the presence of slavery in the UK.

The National Referral Mechanism Statistics – End of Year Summary 2015 was published on February 11th, 2016 and authorised by the OCC and United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre.[87] According to the report it “presents a summary of the number of potential victims of trafficking referred in to the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) in 2015”.[88] The report also establishes a disclaimer which states “This report does not provide any analysis of the picture of human trafficking in the UK. It provides figures relating to the number of potential victims that have been referred in to the NRM process during 2015″.[89]

Through my research of potential victims of human trafficking and modern slavery in the United Kingdom using the NRM Statistics- End of Year Summary 2015 I have gathered the following key points:

- 3266 Potential Victims of Trafficking (PVoT) were referred to the NRM in 2015, a 40% increase from 2014[90]

An increase in the number of human trafficking victims could be due to an increase in people’s vulnerability such as that presented by the recent surge in the migrant crisis across the world or crisis experienced in their countries of origin.

- PVoTs were reported to be from 102 different countries of origin[91]

- Albania, Vietnam and Nigeria were reported to have been the most common countries of origin for referrals[92]

- Biggest increase of country of origin of referred PVoTs was Sudan compared to 2014[93]

- Most common form of adult exploitation for PVoTs was labour exploitation[94]

- Most prevalent form of exploitation for PVoTs first exploited as minors was labour exploitation[95]

- 1744 (53%) of the 3266 referrals were made up of females[96]

- 1518 (46%) were males[97]

- “2 (<1%) [cases] recorded as transsexual and in a further 2 (<1%) cases, the gender was not recorded”[98]

- 2284 (70%) were referrals for adult exploitation and 982 (30%) were for exploitation as a minor[99]

All of the above statistics in the Human Trafficking section of this project have been summarised from the National Referral Mechanism – End of Year Summary 2015.[100]

These statistics show that slavery, specifically modern slavery through human trafficking, is present to a considerable degree within the 21st Century UK. Modern slavery is present in the UK and human trafficking affects both the male and female gender in considerable proportions as well as those who are transsexual. In addition to this the most common exploitation type, because of human trafficking, faced by both adults and minors was labour exploitation. The statistics also highlight that the most common countries of origin for victims of trafficking are those which my research confirmed are identified as lower-middle-income countries, these are Nigeria, Albania and Vietnam. This could suggest that trafficking is more prevalent in these countries as there are high unemployment rates and low standards of living and people could, therefore, be encouraged to move away to higher-income countries and coerced into the prospect of working in such countries through employment opportunities offered by traffickers. Finally, not only does modern slavery exist in the 21st Century United Kingdom through human trafficking, from these statistics it is evident that this crime is increasing and therefore posing an even greater threat to the human rights supposedly supported and defended by the UK government.

How is human trafficking able to take place?

One such legal loophole through which human trafficking is taking place and modern slavery still exists in the 21st Century UK that my research has confirmed is the Overseas Domestic Workers’ visa or the Domestic Worker in a Private Household visa (DWPH visa). Introduced in April 2012 it is a visa which people from “outside the European Economic Area (EEA) and Switzerland”[101] can apply for with their employer if they are “a domestic worker for a private household”[102] or “have worked for your [their] employer for at least one year”.[103] According to the UK government, domestic workers can include “cleaners, chauffeurs, cooks, those providing personal care for the employer and their family [and] nannies”.[104] These workers are eligible to stay in the UK for up to six months, after which they must return home or go when their employer returns home, whichever is sooner.[105]

According to TGSI the tied nature of this visa increases the vulnerability of domestic workers as it is only valid for up to six months, non-renewable and domestic workers are unable to change employers.[106] The implication, therefore, is that workers cannot legally remain in the UK if they should wish to change employers, allowing them to potentially be exploited by their current employers and then be intimidated into not leaving their employment for fear of involvement of the immigration services.[107] Although it is neither the sole nor direct reason for the cause of human trafficking, a form of modern slavery, in the 21st Century United Kingdom, it is dangerously linked to it. This is since the risk of the involvement of the authorities deters employees from reporting abuse or mistreatment, which they may be subject to in their employment, to the police, because if they did so it is likely this would result in termination of their employment and removal to their home country.[108] Cases involving overseas domestic workers in diplomatic households are even more complex. Up to and including throughout 2014, diplomats employing domestic workers possessed an immunity that surpassed the offence of exploitation.[109] According to the Talking Points series Slavery Today issue which “looks at some of the most important and controversial issues facing the world today”[110] by Kaye Stearman between 1980 and 1998, the UK government also regarded these domestic workers “as members of their employer’s households, not as individuals”.[111] This refusal to acknowledge the personal freedoms of domestic workers in diplomatic households went on for 18 years. Stearman is an author and “has worked for international organizations in the field of human rights, minorities, health and development,”[112] she is, therefore, a reliable source who is appropriately experienced and equipped with knowledge of human rights including their abuse through slavery such as trafficking. The Deputy Director of Anti-Slavery International was also a consultant on the book adding to its credibility.

Although this visa is not a direct cause for the occurrence and practice of human trafficking in the 21St Century United Kingdom, it is linked to the vulnerability of overseas domestic workers in the UK and is a legal window contributing to the potential exploitation of human beings who are in the UK on this visa. Many victims feel as though they cannot report abuse for fear of termination of their employment and being forced to return to their home countries.[113] Consequently, this visa legally allows modern slavery through human trafficking and subsequent common labour exploitation to take place in the United Kingdom.

Case Study

Kalayaan is a London based charity established in 1987 by domestic workers and their supporters who aim to provide advice and support to migrant domestic workers in the UK as well as campaign for their rights.[114] According to Kalayaan at the time of its establishment migrant domestic workers were not recognised by immigration rules and therefore came into the country through informal measures, brought by their employers.[115] Providing these workers remained with their employers there were no issues, however, if they decided to leave, for example, due to ill treatment or poor wages, they would be left without formal acknowledgement of their arrival in the UK or their status within it, leaving many in vulnerable positions.[116] Kalayaan state that they were “formed to campaign for the formal recognition of migrant domestic workers in the UK within the immigration rules,” [117] without which it was argued migrant domestic workers would not be able to oppose mistreatment nor defend their rights.[118]

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines domestic workers as people who “work for private households, often without clear terms of employment, unregistered in any book, and excluded from the scope of labour legislation”.[119] According to the ILO, due to their status being potentially unclear, domestic workers can often be exploited for example in terms of receiving low wages, excessive hours, limited rest guarantees and are potentially vulnerable to[120] “physical, mental and sexual abuse or restrictions on freedom of movement”.[121] Such exploitation of domestic workers, according to the ILO, can occur because of labour shortages or chinks within employment laws,[122] demonstrated in the UK by the effect of the restrictions imposed by the Domestic Worker in a Private Household visa.

This trafficking case study is from the Kalayaan website and was published on October 28th, 2014. It is titled “Trafficked,” and is an example of how the Domestic Worker in a Private Household visa contributed to the trafficking, and later labour exploitation, of an individual into the UK and therefore the practice of modern slavery. As the victim of this case wished to remain anonymous,[123] Kalayaan has named them “Regina”.[124] “Regina was brought to the UK by her employer to work in their private household”.[125] Regina explained to Kalayaan that before coming to the UK she had worked for the employer a month before[126] and was promised a “reasonable job and good salary”.[127] The contract which Regina was required to present to the British Embassy as part of her application for a DWPH visa reportedly displayed[128] “excellent terms and conditions and salary”. [129] Regina told Kalayaan that she was made to work in her employers’ apartment situated in central London from 6 am to 11 pm every day, during which time she was not paiyed, nor was she permitted to contact her family or indeed anyone outside of the household.[130] Regina slept in the laundry room, ate leftover food and was regularly verbally abused by her employers.[131] Regina’s employers threatened to cut her wage even though she was not paid it.[132] Regina also cared for a six-year-old child who reportedly verbally and physically abused her.[133] When this was brought to the attention of the child’s mother, she screamed at Regina[134] “and threaten[ed] to jail her in the UK”.[135] Regina said that she could not challenge her employment as her passport was being kept from her and she had nowhere to go.[136] After an incident involving Regina being accused of losing an item of clothing she was kicked out from the household by her employer and was told not to return until she found said item of clothing.[137] Regina could not find it and too frightened to return to the employer she appealed to the reception staff of the apartment block for help who called the police.[138] The police took Regina up to the apartment to retrieve her passport, escorted her to the embassy and left her there.[139] They did not recognise Regina as a trafficked individual, despite the signs nor did they issue her with a crime reference number or their card.[140] Regina’s employers, however, as she understands were given contact details, but she was left essentially helpless, with no money, aid to retrieve her wages or way of returning to her home country.[141]

“Regina’s” experience is just one of the evidently numerous cases of trafficking taking place in the 21st Century United Kingdom, one which has arguably been incurred because of the restrictions imposed by the Domestic Worker in a Private Household visa such as not being able to change your employer. This highlights that even through legal means modern slavery exists within the 21st Century United Kingdom.

Forced Marriage

Although forced marriage may not strike many people as a form of slavery and is not criminalised by the MSA 2015, coercing anyone into a marriage in which either one or both spouses have not consented or are incapable of consent is stripping them of their freedom to choose to get married and is therefore a form of slavery.[142] Forced marriage was, however, made a criminal offence by the UK government according to the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act in 2014.[143] The UK government then established the Forced Marriage Unit (FMU) in January 2015, which is a joint Foreign Office, Commonwealth and Home Office unit intended to carry out the work of the government’s forced marriage legislation.[144] The FMU works both in Britain and overseas helping British nationals as well as dual nationals.[145] Since its establishment, the FMU has dealt with cases from over 90 countries across Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe and North America.[146] According to the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 the following situations regarding marriage are criminal offences:[147]

- “Taking someone overseas to force them to marry (whether or not the forced marriage takes place)

- Marrying someone who lacks the mental capacity to consent to the marriage (whether they’re pressured to or not)

- Breaching a Forced Marriage Protection Order is also a criminal offence”[148]

The FMU provides public and professional help to aid and support victims.[149] According to the FMU forced marriage is recognised in the UK as a form of violence, domestic and child abuse and a violation of human rights [150]and is defined as “a marriage in which one or both spouses do not (or, in the case of some adults with learning or physical disabilities or mental incapacity, cannot) consent to the marriage and violence, threats or any other form of coercion is involved. Coercion may include emotional force, physical force or the threat of physical force and financial pressure “.[151] This is different from an arranged marriage in which “both parties have consented to the union and can refuse to marry if they choose to,”[152] according to the FMU.

Through my research, I have collated and summarised the following statistics on forced marriage and related crimes in the UK from the Forced Marriage Unit Statistics 2015 which was published on the 8th March 2016.[153]

- FMU gave advice to 1,220 potential cases in 2015[154] and “received approximately 350 calls per month”[155]

- 329 cases (27%)of cases involved victims under the age of 18[156]

- 427 cases (35%) involved victims aged 18-25[157]

- 980 cases (80%) involved female victims[158]

- 240 (20%) involved male victims[159]

- “As in previous years, in 2015 the UK region with the greatest number of cases was London (263 cases, 22%>)”[160]

- 29 cases (2%) of the cases dealt with in 2015 involved victims identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender[161]

- 141 cases (12%) dealt with by the FMU in 2015 involved victims with either a physical or learning disability[162]

According to the Forced Marriage Unit Statistics 2015 “In 2015, the FMU handled cases involving 67 ‘focus’ countries which a victim was at risk of, or had already, been taken to in connection with a forced marriage”.[163] The “focus country”[164] is the country to which the forced marriage risk relates, either the country in which a spouse or both are presently living in or the forced marriage is going to take place in.[165] The following are statistics on the five countries with the highest number of cases summarised from the Forced Marriage Unit Statistics 2015 report.[166]

- Pakistan – 539 cases (44%)

- Bangladesh – 89 cases (7%)

- India – 75 cases (6%)

- Somalia – 34 cases (3%)

- Afghanistan – 21 cases (2%)[167]

175 cases (14%) of those dealt with in the UK by the FMU in 2015 had no “overseas element”[168] compared with 23% from 2014, typified by the FMU as “domestic cases”.[169] This reduction in cases could imply that more people are making calls to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as opposed to the FMU.[170]

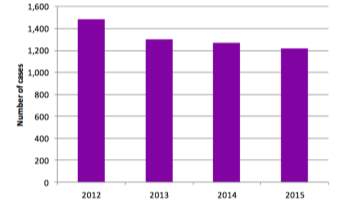

Figure 1:[171]

This graph demonstrates the trend in how the number of calls being made to the FMU has gradually decreased over the course of three years.

Forced marriage is a covert crime and the statistics in the FMU Statistics 2015 only represent the cases brought to the FMU and not the many more which have been concealed – therefore these statistics do not represent the full scale of the offence. However, according to the FMU, a reduction in calls could imply that victims of forced marriage are increasingly reluctant to come forward, fearing retaliation from their families[172] – highlighting the concealed nature of forced marriage. Cases in 2015 ranged from involving very young children to those of an age beyond retirement.[173] Those involving young children often entailed the promise of future marriage as opposed to forthcoming marriage.[174] A minority of those involving older people entailed either the forced marriage having taken place years before or a victim with a learning disability.[175]

Analysis of these statistics show that forced marriage which is a form of modern slavery does exist within the UK predominantly affecting females and those aged between 18-25, however, a considerable proportion of victims of forced marriage related crimes are also male. Slavery regarding forced marriage is also shown to affect those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender dispelling any misconceptions that victims of forced marriage are only heterosexual. Furthermore, these statistics also show that the majority of countries with which forced marriage risks related to were in South Asia and therefore perhaps highlight that forced marriage related crimes that the FMU dealt with in 2015 predominantly affected and existed amongst a minority migrant population of UK nationals.

It is difficult to specify reasons as to why forced marriage is taking place in the 21st Century United Kingdom, however, the FMU is also clear to state that they do not dissect cases by religion and they also note that freely given consent is a prerequisite of Christian, Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Jewish marriages.[176]

The research findings as demonstrated in Section 2 have shown that slavery does still exist within the 21st Century UK, however, following Britain’s abolitionist response to chattel slavery during the 18th and 19th centuries it is in the form of modern slavery which has itself numerous manifestations. The two most predominant forms of modern slavery currently present within the UK are human trafficking and forced marriage both of which affect those of the male and female genders and those classified as adults and minors. Human trafficking is also shown to affect those who are transsexual. These forms of slavery also affect minors and victims from a range of origin countries. Human trafficking in particular also does not only exist within the UK but is an increasing crime.

Section 2

What is being done to combat modern slavery in the 21st Century United Kingdom by the government?

Over the last three years, in particular, the UK government has implemented a number of anti-slavery measures, most predominantly the MSA 2015, advocated by the then Home Secretary Theresa May. The roles of NGO’s such as Kalayaan, Anti-Slavery International and The Global Slavery Index have also increased. The government’s recent efforts were primarily linked to the criminalization of various types of modern slavery, however, there have been fewer developments in decreasing the vulnerability of those already in and those coming to the UK in order to prevent them from being susceptible to modern day enslavement as well as preventing people from committing acts of modern slavery in the first instance.

In 2014, the UK Government established a Modern Slavery Strategy which outlined how the government, law enforcement and NGO’s would address modern slavery.[177] This strategy follows the same structure as that of the Home Office’s approach to defeating terrorism and serious organised crime[178] and is as follows:

- “Pursue: Prosecuting and disrupting individuals and groups responsible for modern slavery

- Prevent: Preventing people from engaging in modern slavery

- Protect: Strengthening safeguards against modern slavery by protecting vulnerable people from exploitation and increasing awareness of and resilience against this crime

- Prepare: Reducing the harm caused by modern slavery through improved victim identification and enhanced support”[179]

This new strategy highlights a commitment to heightening the importance with which modern slavery is regarded and dealt with in the UK.

In addition to this, the landmark MSA 2015 received Royal Assent on Thursday 26th March 2015 and it reinforced existing legislation on a range of forms of modern slavery as well as pivotally increasing the maximum sentence from 14 years to life imprisonment.[180] The Act also importantly includes confiscation of perpetrators assets, the introduction of Slavery and Trafficking Prevention Orders and Slavery and Trafficking Risk Orders[181] “to restrict the activity of individuals where they pose a risk of causing harm,”[182] and increased law enforcement powers at sea.[183] After pressure from parliamentarians and the voluntary sector, the Act also includes provisions for victims of modern slavery.[184]

According to Prime Minister Theresa May, the MSA 2015 is “the first legislation of its kind in Europe”.[185] May also argues that it has made many achievements which include being a tool to prevent convicted traffickers from travelling to countries where they have been known to previously exploit vulnerable people, provided improved protection and support for victims and leading worldwide transparency of business to prove that modern slavery is not taking place in their companies or supply chains.[186]

Part 4 of the MSA 2015 also established a key new role in the fight against modern slavery in the 21st Century UK, the position of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner.[187] According to the Independent Anti- Slavery Commissioner’s website the Commissioner’s role is detailed and involves encouraging effective practice in the “prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of slavery and human trafficking offenses, as well as in the identification of victims,”[188] consistently across the UK. The Commissioner is also required to submit annual reports to Parliament relating how well objectives have been achieved.[189]

The first and current Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner is Kevin Hyland.[190] Hyland was formerly head of the London Metropolitan Police Service’s Human Trafficking Unit and worked as an officer for 30 years, specialising in the investigation of “serious organized crime”.[191]

In an interview by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, an international organisation fighting against modern slavery and human trafficking,[192] in October 2016 Hyland stated that prevention of modern slavery would include a “three-pronged attack in many areas”.[193] This involves working alongside communities to ensure awareness of the risks of modern slavery and dispelling fabrications made by criminals that the UK, along with other parts of Europe,[194] are “places where you can earn fortunes and live these lavish lifestyles”.[195] Following this, Hyland suggests the provision of opportunities such as jobs so that people are less likely to take[196] “dangerous risks to leave their own places but also so the criminals again haven’t got an easy job”.[197] The final part of this approach is ensuring the enforcement and fulfilment of the Rule of Law.[198] According to Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary it is classically “the doctrine of English law expounded by Dicey, in Law of the Constitution, that all men are equal before the law, whether they be officials or not…so that the acts of the officials carrying out the behests of the executive government are cognizable by the ordinary courts and judged by the ordinary law…”. [199] In criticism of the UK’s approach to modern slavery Hyland states that not enough appropriate resources are being designated to the fight against it nor is there enough coordination[200] and consequently “the criminals are acting with impunity”.[201] Hyland also argues that for too long the UK has not viewed modern slavery as “a serious organized crime”.[202] Finally, Hyland states that in response to low numbers of prosecutions once these resources, methods and strategies begin to be utilised and more work is done with countries of origin, prosecutions will begin to change.[203]

Another specific example of the UK’s work to combat modern slavery are the repeal demands for the tied Domestic Workers in a Private Household Visa which has been linked to the vulnerability of victims of human trafficking. On the 2nd of December 2015, the London Assembly made a call to then Home Secretary Theresa May[204] “to make the case to repeal the tied visa system”.[205] In response to this May requested an independent review of the visa[206] by barrister James Ewins. According to the review, the “existence of a tie to a specific employer and the absence of a universal right to change employer and apply for extensions of the visa are incompatible with the reasonable protection of overseas domestic workers“.[207] Therefore, despite the call, the visa still currently remains in place and it is unclear what the UK Government’s plans are surrounding it.

According to an article on the guardian website, regarding the independent review, the then Immigration Minister James Brokenshire argued to MP’s that the Government’s concern was that allowing overseas domestic workers (ODW’s) to change jobs whilst in Britain would decrease the likelihood of them reporting abusive employers.[208] Brokenshire stated that it would instead “perpetuate a revolving door of abuse in which perpetrators remain unidentified and free to bring other domestic workers to the United Kingdom with impunity”.[209] By this, it can be understood that Brokenshire believes that if ODW’s are permitted to change employers during their stay in the UK and they are subject to abuse or mistreatment by their employers they would have the opportunity to instead move on to a different employer and not feel the need to report their current one. This would mean that abusive employers or those who do not treat ODW’s appropriately would go unreported and instead be able to continue with their abusive behaviour, enacting it upon other ODWs whom they may employ in the future. The article also, however, reports that the Home Office stated that they would, instead of repealing the visa, provide an[210] “immediate escape route”[211] providing the reported “17,000”[212] people a year that come to the UK on DWPH visas the “right to switch employers within their first six months in the country”.[213] Those found to be victims of abuse “can stay in the country from six months to two years”.[214] In view of the whole argument, as the visa remains, such reforms could be interpreted as concessions by the Home Office and are still a long way from preventing human trafficking, a form of modern slavery, in the 21st Century UK.

Section 3

How effective are anti-modern Slavery efforts in the 21st Century United Kingdom?

The effectiveness of the anti-slavery measures put into place by the UK government in regard to eliminating modern slavery is contentious as although a number of them have set a precedent in the fight against modern slavery within the UK, they could arguably be considered as only establishing the groundwork in eliminating slavery. The development of these anti-slavery measures is required to permeate all areas of modern slavery, most importantly eliminating the vulnerability of potential victims in the first instance as it is through susceptibility to exploitation that people are lured into and trapped by modern slavery. Reducing the vulnerability of people and therefore decreasing the number of potential victims of modern slavery is arguably more effective than intimidating perpetrators through punishments as although effective, those responsible for carrying out modern slavery are likely to still do so if their potential victims are still vulnerable and able to be coerced or forced, regardless of the risks. This method of combating modern slavery is, however, arguably more applicable to eliminating human trafficking than forced marriage, therefore, the UK government also need to develop their response to preventing forced marriage from taking place although this may first require the clearer identification of why it is happening and how people can be susceptible to it.

In 2016 the MSA 2015 underwent an independent review by barrister Caroline Haughey, which was commissioned by Prime Minister Theresa May in her previous role as Home Secretary. The findings of the review are outlined in the 2016 Report of the Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group (IDMG) on Modern Slavery which is a group that produces updates on the government’s strategy to inhibiting modern slavery.[215] According to the report summary, the independent review found that the MSA 2015 established an “international benchmark to which other jurisdictions aspire” [216], however, there is “a lack of consistency in how police and criminal justice agencies deal with victims and perpetrators of modern slavery”.[217] This is an enforcement and protection issue and therefore implies that there is yet far more work to be done and the act is not fulfilling its potential effectiveness.

Following the reported findings of the review, the UK Government announced a significant £33.5m investment[218] “of official development assistance to support victims and bring perpetrators to justice by working in partnership with key source countries, civil society, businesses and consumers”.[219] This money is going towards tackling modern slavery in countries where victims are regularly trafficked to the UK, for example at least of £5m of it will be spent Nigeria.[220] As well as this monetary investment, the Prime Minister also announced in July 2016, in the wake of the review, the establishment of a modern slavery taskforce[221] “to pioneer a more coordinated policy and operational response to modern slavery”.[222] The taskforce’s objectives include improved use of:[223] resources, investigations, “international collaboration”[224] and “increased education of prosecuting authorities”[225] about modern slavery.

Despite such responses by the government to independent reviews, few measures are in place to decrease people’s vulnerability when in or travelling to the United Kingdom to avoid falling into the snare of modern day enslavement. Additionally, despite the MSA 2015 requiring businesses to be transparent in proving that modern slavery is not taking place in their supply chains, there are no formal repercussions for those making no effort to examine their supply chains nor is there an enforcement agency.[226]

The 2016 report by the IDGM on modern slavery does, however, outline the UK’s intended future response to tackling modern slavery. This included continued efforts to guarantee that legislation, tools and strategies currently in place in the UK are fully enforced and are operating efficiently to ensure the protection of victims and perpetrators being brought to justice.[227] Finally, as well as ensuring the response to modern slavery is alongside that of other serious crimes[228] the UK government state that they intend to also particularly focus on “enhancing our international cooperation with key source countries to try to prevent vulnerable people from becoming victims in the first place”.[229] This claimed intention of the UK government of preventing people living in and coming to the country from being in a position in which they are susceptible to falling into the hands of modern enslavement perpetrators is one that is a key factor, as it regards vulnerability, in the fight against modern slavery in the 21st Century UK.

In order to better protect people, the vulnerability of potential victims my research suggests could be reduced by ensuring that the UK government has “accurate information”[230] of its population in order to protect it to their best ability. This is corroborated by social geographer Danny Dorling in his book So You Think You Know About Britain? an analysis of modern-day Britain, in which he argues in the chapter “Overkeen, Underpaid and Over Here”[231] that the UK government’s methods of measuring the population have been inherently inaccurate.[232] This could highlight one of the reasons as to why so many potential victims of modern slavery, from foreign countries, exist in the United Kingdom as their presence in the UK is not being officially recorded. Therefore, they do not appear, in the eyes of the government, to be a part of the population which the government is committed to safeguarding and are consequently at risk of exploitation.

Conclusion

Over the course of this project, I have investigated the reality of the existence of slavery in the 21st Century United Kingdom, the extent of it within the country, the methods undertaken by the UK government to combat it, as well as how effective these methods have been. Despite modern slavery being an overarching term it can be summarised as stripping a person of their essential freedoms through coercion and trickery, which in the 21st century has manifested into numerous forms. Modern slavery is a hidden crime, both its victims and perpetrators walk amongst us every day and this research project has shown that it does exist within the 21st Century United Kingdom and most prominently in the forms of human trafficking with a view of exploitation of the victim, most commonly forced labour, and in the form of forced marriage. In addition to this, human trafficking is not only taking place in the UK but reports made to the NRM are increasing, considering this and the number of cases which presumably go unreported for various reasons, modern slavery is a growing threat to human rights.

One of the key arguments as to why human trafficking is taking place in the 21st Century UK is the initial vulnerability of victims which is primarily linked to the tied DWPH visa system currently in place in the UK.[233] Without the ability to change employers whilst in the UK or inform the authorities for fear of employment termination and being forced to return to their home country[234] victims are left trapped and in a vicious cycle. This is despite the claims of former Immigration Minister James Brokenshire that allowing ODWs to change employment when in the UK will result in a “revolving door of abuse…”[235] as those who have in fact been trafficked are suffering abuse of their human rights which they cannot escape and is not being penalised. Ultimately modern slavery is taking place on both a global and national scale that has gone unrecognized for far too long and despite the UK government’s successful efforts to increase the punishments for it as well as improve provisions for victims, in the most notable form of the MSA 2015, it is paramount that they develop efforts to decrease the vulnerability of potential victims. By bringing an end to legal loopholes for exploitation, such as the Domestic Worker in a Private Household visa and the restrictions they impose, as well as increasing the government’s knowledge of their population the UK government’s anti-slavery measures will arguably take a decisive step towards ending the practice of modern slavery in the 21st Century United Kingdom. It should mean that fewer people are in a position in which they can be subjugated and exploited.

In relation to forced marriage, a possible improvement on the government response to it could be to acknowledge it as a form of modern slavery, as it does fundamentally involve stripping a person of their freedom, and therefore criminalise it under the MSA 2015. This would also ensure that future government responses to modern slavery would also encompass the covert crime of forced marriage which is a human rights abuse.

Tackling the complex issue of modern slavery on a national, let alone global scale, is evidently going to remain a challenging issue for the near future, however, identifying the extent of its confirmed presence in the United Kingdom and assessing the efficiency of current combating measures in place, in order to enhance them, is a significant place to begin in the fight against it.

Bibliography

Websites

Anti-Slavery International, Unknown. Frequently Asked Questions: What is modern slavery?. [Online] Available at: http://www.antislavery.org/english/who_we_are/english/who_we_are/english/who_we_are/frequently_asked_questions.aspx#2.%20What%20is%20modern%20slavery?

[Accessed 3 January 2017].

Anti-Slavery International, Unknown. Who We Are. [Online] Available at: http://www.antislavery.org/english/who_we_are/english/who_we_are/english/who_we_are/antislavery_international_today.aspx [Accessed 3 January 2017].

BBC Devon, 2007. Abolition: England’s first slave trader. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/content/articles/2007/01/18/abolition_plymouth_slave_trade_feature.shtml [Accessed 9 November 2016].

BBC History, 2011. The First Black Britons. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/black_britons_01.shtml [Accessed 9 November 2016].

BBC History, 2011. The First Black Britons. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/black_britons_01.shtml [Accessed 9 November 2016].

BBC History, 2011. The First Black Britons. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/black_britons_01.shtml [Accessed 9 November 2016].

Government Digital Services, 2016. Countries in the EU and EEA. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/eu-eea [Accessed 10 January 2017].

Government Digital Services, 2016. Domestic Workers in a Private Household visa Overview. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/domestic-workers-in-a-private-household-visa/overview [Accessed 10 January 2017].

Government Digital Services, 2016. Domestic Workers in a Private Household visa Your employment rights. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/domestic-workers-in-a-private-household-visa/your-employment-rights [Accessed 10 January 2017].

Government Digital Services, 2016. Forced Marriage Legislation on Forced Marriage. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/forced-marriage#legislation-on-forced-marriage [Accessed 6 January 2017].

Government Digital Services, 2016. Forced Marriage Overview. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/forced-marriage#legislation-on-forced-marriage [Accessed 6 January 2017].

Henry, N. L., 2016. Slavery Abolition Act United Kingdom [1834]. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Slavery-Abolition-Act [Accessed 13 November 2016].

Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017. About the Commissioner. [Online]

Available at: http://www.antislaverycommissioner.co.uk/about-the-commissioner/the-commissioner/ [Accessed 19 February 2017].

Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017. History of Slavery. [Online] Available at: http://www.antislaverycommissioner.co.uk/about-modern-slavery/history-of-slavery/ [Accessed 8 April 2017].

International Criminal Police Organisation, Unknown. Crime Areas: Trafficking in Human Beings. [Online] Available at: https://www.interpol.int/Crime-areas/Trafficking-in-human-beings/Trafficking-in-human-beings [Accessed 5 January 2017].

International Labour Organization, Unknown. Who are domestic workers?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/docs/WCMS_209773/lang–en/index.htm [Accessed 6 January 2017].

Kalayaan, 2014. Case Study 1: Trafficked. [Online] Available at: http://www.kalayaan.org.uk/case-study/case-study-1-trafficked/ [Accessed 6 January 2017].

Kalayaan, Unknown. About Us: Our History. [Online] Available at: http://www.kalayaan.org.uk/about-us/our-history/ [Accessed 10 January 2017].

May, T., 2016. Defeating modern slavery: article by Theresa May. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/defeating-modern-slavery-theresa-may-article [Accessed 19 February 2017].

Morris, Marc, Unknown. 10 surprising facts about William the Conqueror and the Norman Conquest. [Online] Available at: http://www.historyextra.com/article/bbc-history-magazine/10-facts-william-conqueror-norman-conquest [Accessed 19 April 2017].

National Crime Agency, Unknown. About Us: Our Mission. [Online] Available at: http://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/about-us [Accessed 29 March 2017].

National Crime Agency, Unknown. Modern Slavery Human Trafficking Unit (MSHTU). [Online] Available at: http://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/about-us/what-we-do/specialist-capabilities/uk-human-trafficking-centre [Accessed 29 March 2017].

National Crime Agency, Unknown. National Referral Mechanism. [Online] Available at: http://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/about-us/what-we-do/specialist-capabilities/uk-human-trafficking-centre/national-referral-mechanism [Accessed 29 March 2017].

Oxford University Press, 2015. Oxford English Dictionary Quick search. [Online] Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/181500?rskey=pTZrHo&result=1#eid [Accessed 7 January 2017].

Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dicitionary Quick search. [Online] Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/181477?rskey=lG8HqF&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid [Accessed 23 December 2016].

Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dictionary Quick search. [Online]

Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/190286?rskey=fQnpTH&result=2#eid [Accessed 7th January 2017].

Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dictionary Quick search. [Online] Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/23449?rskey=f3fibm&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid [Accessed 7th January 2017].

Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dictionary Quick search. [Online] Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/181498?rskey=BatxdI&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid [Accessed 9 November 2016].

Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dictionary Quick search. [Online]

Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/181477?rskey=hwQemJ&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid [Accessed 7 January 2017].

Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dictionary Quick search. [Online]

Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/66261?redirectedFrom=exist#eid [Accessed 7 January 2017].

Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2017. Slave Trade 1807. [Online]

Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slave_Trade_Act_1807 [Accessed 14 March 2017].

Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Dowing Street and The RT Hon Theresa May MP, 2016. Press Release: Prime Minister urges international action to stamp out modern slavery. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-calls-for-global-action-to-stamp-out-modern-slavery [Accessed 19 February 2017].

Sandhu, S., 2011. The First Black Britons. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/black_britons_01.shtml [Accessed 9 November 2016].

The British Library, 2016. Minutes of Committee for Abolition of Slavery. [Online]

Available at: https://www.bl.uk/taking-liberties/articles/minutes-of-committee-for-abolition-of-slavery [Accessed 23 December 2016].

The Global Slavery Index, Unknown. About The Global Slavery Index. [Online]

Available at: http://www.globalslaveryindex.org/about/ [Accessed 6 January 2017].

The Global Slavery Index, Unknown. Country Study: United Kingdom. [Online]

Available at: http://www.globalslaveryindex.org/country/united-kingdom/ [Accessed 5 January 2017].

The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown. Slave or Free?. [Online] Available at: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/slave_free.htm [Accessed 9 November 2016].

Thomson Reuters Foundation, 2014. Who we are and what we do. [Online] Available at: http://about.trust.org/who-we-are-and-what-we-do/ [Accessed 13 April 2017].

The University of Chicago Law Review, Unknown. The University of Chicago Law Review Description. [Online] Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1599128?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=Somerset&searchText=vs.&searchText=Stewart&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3Ffilter%3Ddisc%253Alaw-discipline%26amp%3BQuery%3DSomerset%2Bvs.%2BStewart&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 29 March 2017].

Travis, A., 2016. Government rejects call to end UK tied visas for domestic workers. [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/mar/07/government-rejects-call-scrap-uk-tied-visas-domestic-workers [Accessed 5 January 2017].

United Nations, Unknown. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. [Online]

Available at: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ [Accessed 10 November 2016].

Walk Free Foundation, Unknown. About the Foundation. [Online] Available at: http://www.walkfreefoundation.org/about/ [Accessed 5 January 2017].

Documents from websites and PDFs

The National Archives, Unknown. Abolition. [Online] Available at: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/slavery/pdf/abolition.pdf [Accessed 15 April 2017].

The National Archives, Unknown. Britain and The Slave Trade. [Online] Available at: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/slavery/pdf/britain-and-the-trade.pdf [Accessed 9 November 2016].

Journals

Wiecek, M. W., 1974. Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World. The University of Chicago Law Review, 42(1), p. 61.

Books

Dorling, D., 2011. Overkeen, Underpaid and Over Here – Immigration. In: Unknown, ed. So You Think You Know About Britain?. London: Constable , p. 308.

Stearman, K., 1999. Breaking the chains: Human Rights. In: A. Edmonds, ed. Slavery Today – (Talking Points). London: Wayland Publishers, p. 64.

Stearman, K., 1999. Migrant Workers: Unfair contracts. In: A. Edmonds, ed. Slavery Today – (Talking Points). London: Wayland Publishers, p. 64.

Stearman, K., 1999. Slavery Today – (Talking Points). In: A. Edmonds, ed. Slavery Today. London: Wayland Publishers, p. 64.

Stearman, K., 2008. Human Trafficking. 1st Edition ed. London: Wayland Publishers.

Woodley, M., 2013. Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary. 12th Edition ed. London: Sweet & Maxwell.

Parliamentary Acts

Parliament of the United Kingdom, 1807. Slave Trade Act 1807. London: Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2015. Modern Slavery Act 2015. London: Home Office

Government publications

Ewins, J., 2015. Independent Review of the Overseas Domestic Workers Visa, s.l.: Home Office and UK Visas and Immigration.

Interviews

Hyland, K., 2016. Interview: Kevin Hyland, UK Anti-Slavery Commissioner [Interview] (12 October 2016).

Graphs

Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016. Number of cases the FMU gave advice or support to, 2012 to 2015. London: s.n.

Reports

Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016. Forced Marriage Unit Statistics 2015, London: Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office.

Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016. Report of the inter-departmental ministerial group on modern slavery 2016, London: Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery.

Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016. National Referral Mechanism – End of Year Summary 2015, London: National Crime Agency.

Miscellaneous

United Nations, 1956. Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similiar to Slavery Preamble. Geneva: United Nations.

[1] (Oxford University Press, 2016)

[2] (United Nations, 1956)

[3] (Oxford University Press, 2016)

[4] (Stearman, 2008)

[5] (The British Library, 2016)

[6] (Morris, Unknown)

[7] (The British Library , 2016)

[8] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[9] (BBC Devon, 2007)

[10] (BBC Devon, 2007)

[11] (BBC Devon, 2007)

[12] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[13](BBC Devon, 2007)

[14] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[15] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[16] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[17] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[18] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[19] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[20] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[21] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[22] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[23] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[24] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[25] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[26] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[27] (Sandhu, 2011)

[28] (Sandhu, 2011)

[29] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[30] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[31] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[32] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[33] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[34] (Woodley, 2013)

[35] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[36] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[37] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[38] (Wiecek, 1974)

[39] (Wiecek, 1974)

[40] (The National Archives and the Black and Asian Studies Association, Unknown)

[41] (The University of Chicago Law Review, Unknown)

[42] (Wiecek, 1974)

[43] (Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2017)

[44] (Parliament of the United Kingdom, 1807)

[45] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[46] (The National Archives, Unknown)

[47] (Henry, 2016)

[48] (Henry, 2016)

[49] (Henry, 2016)

[50] (United Nations, Unknown)

[51] (United Nations, Unknown)

[52] (United Nations, Unknown)

[53] (Stearman, 1999)

[54] (United Nations, Unknown)

[55] (United Nations, Unknown)

[56] (United Nations, 1956)

[57] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[58] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[59] (Stearman, 2008)

[60] (Stearman, 2008)

[61] (Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2015)

[62] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[63] (Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2015)

[64] (Parliament of the United Kingdom , 2015)

[65] (International Criminal Police Organisation, Unknown)

[66] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[67] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[68] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[69] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[70] (Anti-Slavery International, Unknown)

[71] (Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017)

[72] (Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017)

[73] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[74] (Walk Free Foundation, Unknown)

[75] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[76] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[77] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[78] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[79] (Parliament of the United Kingdom, 2015)

[80] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[81] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[82] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[83] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[84] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[85] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[86] (National Crime Agency, Unknown)

[87] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[88] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[89] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[90] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[91] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[92] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[93] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[94] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[95] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[96] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[97] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[98] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[99] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[100] (Organised Crime Command/ United Kingdom Human Trafficking Centre, 2016)

[101] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[102] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[103] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[104] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[105] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[106] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[107] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[108] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[109] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[110] (Stearman, 1999)

[111] (Stearman, 1999)

[112] (Stearman, 1999)

[113] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[114] (Kalayaan, Unknown)

[115] (Kalayaan, Unknown)

[116] (Kalayaan, Unknown)

[117] (Kalayaan, Unknown)

[118] (Kalayaan, Unknown)

[119] (International Labour Organization, Unknown)

[120] (International Labour Organization, Unknown)

[121] (International Labour Organization, Unknown)

[122] (International Labour Organization, Unknown)

[123] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[124] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[125] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[126] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[127] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[128] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[129] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[130] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[131] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[132] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[133] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[134] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[135] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[136] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[137] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[138] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[139] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[140] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[141] (Kalayaan, 2014)

[142] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[143] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[144] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[145] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[146] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[147] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[148] (Government Digital Services , 2016)

[149] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[150] (Government Digital Services, 2016)

[151] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[152] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[153] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[154] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[155] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[156] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[157] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[158] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[159] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[160] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[161] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[162] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[163] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[164] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[165] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[166] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[167] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[168] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[169] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[170] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[171] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[172] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[173] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[174] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[175] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[176] (Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Home Office, 2016)

[177] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[178] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[179] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[180] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[181] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[182] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[183] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[184] (The Global Slavery Index, Unknown)

[185] (May, 2016)

[186] (May, 2016)

[187] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[188] (Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017)

[189] (Inter-Departmental Ministerial Group on Modern Slavery, 2016)

[190] (Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017)

[191] (Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, 2017)

[192] (Thomson Reuters Foundation, 2014)

[193] (Hyland, 2016)

[194] (Hyland, 2016)

[195] (Hyland, 2016)

[196] (Hyland, 2016)

[197] (Hyland, 2016)

[198] (Hyland, 2016)

[199] (Woodley, 2013)

[200] (Hyland, 2016)

[201] (Hyland, 2016)

[202] (Hyland, 2016)