Signs of Metabolic Syndrome in Schizophrenic Patients Taking Atypical Antipsychotics

Info: 15333 words (61 pages) Dissertation

Published: 16th Dec 2019

Tagged: Mental HealthPsychiatry

Recognizing the Signs of Metabolic Syndrome in Schizophrenic Patients Taking Atypical Antipsychotics in the Primary Care Setting

Doris A. Davis

Armstrong State University

Recognizing the Signs of Metabolic Syndrome in Schizophrenic Patients Taking Atypical Antipsychotics in the Primary Care Setting

It is estimated that 1.1% of adults in the United States (U.S.) live with schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009). In comparison to those without schizophrenia, patients with this disorder are greater than 3.5 times more likely to die two decades earlier from cardiovascular disease or its complications (NIMH, 2009). Cardiovascular disease has the highest mortality rate (403.2 per 100,000 person-years) and is accountable for nearly a third of all natural U.S. deaths (Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal, & Stroup, 2015; Preidt, 2015). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Health Statistics Report of 2009, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome increases the risks for cardiovascular disease and increased mortality, and nearly 35% of the U.S. population age 20 years and over meets the criteria for metabolic syndrome (Ervin, 2009).

Atypical antipsychotics (AAPs), introduced for use in the late 1990s, have since become the most frequently prescribed and utilized management for patients suffering from an assortment of psychotic-related illnesses (Kang & Lee, 2015). Convincing evidence suggests the use of AAPs are directly associated with severe metabolic adverse effects, such as obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Kang & Lee, 2015). These metabolic disorders are associated with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular diseases, further linking its use to early mortality (Kang & Lee, 2015). The metabolic adverse effects associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics do not just cause an increase in mortality; their use will, in addition, further complicate and exacerbate the clinical course and capabilities of patients under their treatment (Demirel, Demirel, & Ugur, 2015).

It is highly significant that the formally educated medical professional in the primary care sector becomes proficient in the identification of mental disorders, and be cognizant of the existing resources available for further evaluation and initiation of early treatment (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). It is equally critical to understand, as future advanced practice nurses with a focus on primary care, that psychiatric disorders are associated with increased medical morbidity and mortality that are greatly contributable to the treatable medical condition cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). Recognition and management of these conditions in patients with psychiatric infirmities are complicated because of barriers related to the patient, the illness, the attitudes of the clinicians, along with the makeup and organization of healthcare delivery services (Bajaj, Varma, Srivastava, & Verma, 2013).

In light of the increasing amount of evidence suggesting a relationship between atypical antipsychotic medications and metabolic syndrome, it is recommended that routine medical monitoring of weight, glucose, and other indicators of hyperglycemia become the standard for all patients chronically medicated with atypical antipsychotics (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011). With that, patients treated with atypical antipsychotics should be screened regularly in reference to their metabolic status (Demirel, Demirel, & Ugur, 2015).

Statement of the Problem

Recognizing the associated signs of metabolic syndrome early, in addition to appropriate interventions and treatment can improve the long-term health outcomes of patients being serviced in the primary care setting (Hoffman, VonWald, & Hansen, 2015). Atypical antipsychotics are frequently being used in the primary care setting to treat the abnormal symptoms associated with and experienced by patients with schizophrenia. These medications can cause metabolic abnormalities placing the patients at an increased risk of non-compliance, further exacerbating the psychotic features of their disease processes, as well as cardiovascular mortalities (Demirel, Demirel, & Ugur, 2015).

Definitive rationales for the increased cardiovascular risk are complex when taking AAPs; however, it has been significantly contributory to the multifarious linking of schizophrenia-related factors, poverty, unhealthy lifestyle, poor quality health screening and care, in addition to the adverse effects of treatment (Corell, et al., 2014). Research shows that schizophrenia and schizoaffective related disorders occur in more than one percent of the American populace age 18 years or older; an equivalent to roughly 2.2 million Americans. This contributes to a considerable impact on healthcare consumption and costs (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011). Multiple studies support the conclusion that appropriate and effective monitoring of metabolic changes are not being provided to schizophrenic patients taking atypical antipsychotics in the primary care setting (Mittal, Li, Williams, Viverito, Landes, & Owen, 2013). With acknowledgement of this information, it can be appreciated that to reduce the prevalence of cardiovascular mortality, improved awareness of metabolic syndrome as a risk factor in the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD), as well as the adoption of an appropriately associated guide for screening, monitoring, and treatment are required (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011).

Schizophrenic patients with metabolic syndrome have an increased rate of coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke compared to patients with any singular factor of hypertension, insulin-resistance, dyslipidemia, or obesity. The risk of these conditions is further augmented by the use of psychotropic medications, and the risk may be greater with the use of many second-generation antipsychotic agents (Bajaj, Varma, Srivastava, & Verma, 2013). Interventions are needed to promote the mental and physical health of individuals with severe mental disorders. There is a great need for access to quality and proficient patient-centered care for patients with mental disorders to improve the diagnosis and treatment of coexisting physical conditions (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015).

Significance of the Problem

There is an increase in mental health patients being seen in the primary care setting after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (Olsen, 2014). Incorporating mental health into the primary care setting can be directly related to a lack of insurance and the requirement of health insurance plans to cover depression screening for adults and behavioral assessments for children as preventative services (Olsen, 2014). As a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), greater than 62 million Americans will have access to mental health and substance abuse care. Many of the health plans included in the ACA are required to cover primary and preventive services signifying that more patients will be turning to the primary care clinicians for initiation and maintenance of emotional and behavioral health problems (Olsen, 2014). In 2010, 18 percent of all visits to Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs) included at least one mental health indicator, which included screening, counseling, or diagnosis of a mental illness as the primary reason for the visit (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). The request, necessity, or application of a psychotropic drug was also included as part of these visits (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015).

The anticipated need for primary care services is projected to increase through year 2020. The supply, through 2010, of physicians in the primary care setting is significantly lower than the demand, and the demand for primary care physicians is anticipated to grow faster than their supply through year 2020 (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2013). The percentage of mental health–related visits to primary care sites serviced by APRNs increased with age through age 59 years (CDC, 2014) and these patients either have no healthcare insurance or are insured with plans requiring the initiation of medical care via primary care first (Freundlich, 2013; Primary Care Progress [PCP], 2016).

Patients suffering from schizophrenia and schizoaffective related disorders have a quadruple risk of developing metabolic syndrome (Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, & Bellomo, 2015). They are more likely to smoke, have a poorer quality diet, and are less likely to be physically active. Studies show that they have increased psychotic and depressive symptoms, in addition to a decreased compliance with disease process management (Flynn, Houtjes, Merks, Mierlo, & Van De Wetering, 2015). Despite these risks, these patients are less likely to initiate primary health care, and their overall mental health statuses are rarely undertaken within psychiatric settings. Appropriate and early screening of patients for signs of metabolic syndrome during the treatment course of atypical antipsychotics is crucial in decreasing their occurrence and death rate of cardiovascular disease and its precursors (Flynn, Houtjes, Merks, Mierlo, & Van De Wetering, 2015). When metabolic derangement develops into a disorder, then management guidelines particular to that disorder dictates intervention. Pharmacotherapeutic management should not negate non-pharmacologic approaches (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011). It is recommended that the standard for this care include the primary care provider and the psychiatrist working together, facilitating improved patient care (Mangurian, et al., 2013; Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011).

Role of the Advanced Practice Nurse

The advanced practice nurse is highly capable of assessing all patients under their care for cardiometabolic risks prior to and during treatment management (Thomas A. , et al., 2014). APRNs are accomplished in initiating changes and providing interventions as they are warranted to increase the probability of wellness and decrease the death rate of patients being treated in the primary care setting who are on atypical antipsychotics (Thomas, et al., 2012). With the anticipated expansion of insurance coverage under the affordable Care Act and population aging and growth, the demand for primary care services is predicted to increase along with the supply of primary care nurse practitioners (NPs). The prevalence of primary care nurse practitioners are projected to increase by approximately 30 percent by year 2020, a rate which is more rapidly growing than the current physician supply and it is further projected that the utilization of nurse practitioners to their full potential could alleviate the projected 2020 primary care physician shortage (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2013).

Primary care is essential to an effective, efficient health care system. For many individuals, the primary health care providers are the initial contact with the health care system (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). The nurse practitioners of primary care diagnose and treat common illnesses and identify minor medical issues before they become serious ones. They offer preventive services and counseling, and play an overall significant role in managing the care of patients with chronic health conditions (Freundlich, 2013). Advanced practice nurses care for their patients across the continuum of their care. They are the first point of contact for undiagnosed medical issues and provide comprehensive patient-centered care (PCP, 2016).

Statement of Purpose

The purpose of this project is to educate APRN’s on recognizing the signs of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic patients taking atypical antipsychotics in the primary care setting. The enactment of the Affordable Care Act along with an increased population of uninsured patients has increased the number of mental health patients being seen in the primary care settings under the care of advanced practice nurses (Olsen, 2014). Articles written by Mittal, Li, Williams, Viverito, Landes, & Owen (2013) and Nasrallah (2012) suggest that patients with schizophrenia, being treated with atypical antipsychotics are not being effectively monitored for the negative side effects associated with the treatment class of medications. The lack of this intervention directly places those patients at an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (CDC, 2014). There are multiple evidence-based recommendations detailing how to correct this very unfortunate miscarriage of care (Cenpatigo Integrated Care, 2016) and the advanced practice nurse is highly capable of providing this service in the primary care setting (Thomas, A., et al., 2014).

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this project is based on the Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior, a theoretical prescription for nursing by Cheryl L. Cox, RN, PhD. The Interactive Model of Client Health Behavior (IMCHB) was initially created in response to a noted deficiency in studies recognizing or identifying the client as the focal entity responsible for the outcomes of his or her medical care. This framework was also created because of a decrease in models supporting the association between the client needs and nursing interventions and the outcomes of client health as a result of advanced nursing intervention (Cox, 1982). This model was additionally developed to address the need for a client-focused theoretical framework to explain the relationship between the patients’ personal and environmental variables affecting positive health outcomes and the client-provider relationship influencing these outcomes. Cox investigated and created this theory based upon her conviction that way of life, actions and activities played a fundamental position in a patient’s responsibility to their existing health care problems and for that reason, today’s interventions must insist that clients take a more energetic, informed and autonomous role in both their health status and outcomes (Cox, 1982).

The IMCHB serves as a strong foundation on which to base the current knowledge and guiding principle in the importance of the role of the advance practice nurse in assessing, diagnosing, planning, intervening, and evaluating abnormal findings for the patients under their direct care. This model discusses, explains and contributes to the roles, relationships, and positive outcomes of the interactions between the patient and the practitioner. An additional rationale for using the IMCHB as the theoretical foundation for this topic and project was to utilize its resources to recognize and recommend associated interactions between patient singularity, patient-provider affiliation and consequent patient health care performance (Cox, 1982). The use of this model is not limited to the practice setting, suggesting its use applicability to any healthcare atmosphere (Cox, 1982).

The creation of this model was to explain and validate the successfulness of outcomes based on the relationship between client needs and nursing interventions. Dr. Cox suggested that while nurses served in advanced roles, the patient as an individual, the interaction between patient and professional, and the healthcare outcomes, because of nursing intervention had not been effectively investigated and confirmed. The processes proposed through the IMCHB was to (1) recognize patient individualism in achieving positive health outcomes, (2) recognize the concepts that structure client-clinician professional interaction in reaching positive health outcomes, and (3) direct the development of nursing interventions that focuses on the patient and their critically required health care. This model was purposed by Dr. Cox to recognize and recommend descriptive associations connecting client singularity, client-clinician relationships and the consequential client health care behavior (Cox, 1982). The three principles of Cox’s IMCHB are singularity, client-professional relationship, and overall health outcomes (Cox, 1982).

Client singularity focuses on the unique and individualized elements of the patient (Cox, 1986). The proficient clinician considers the essentials of client singularity; background variables, emotional reaction, cognitive appraisal, inherent motivation, expression of motivation, estimation of the health care concern and the emotional response to that concern, and applies these concepts to the promotion of client centered care (Cox, 1982). Background variables are the patients’ demographics, impact and influence of their communal society, previous occurrences and understanding of health care and situational resources (Cox, 1982). These variables interrelate over time and manipulate specific health behaviors. Motivation recognizes choice, desire, and the need for competency and self-determinism as causal factors in behavior.

The client-professional relationship proposes a mutual commitment between client singularity, communication, and health care results. This relationship has a major influence on healthcare activities and performance. There are four components to this category; health information, affective support, decisional control, and professional and technical competencies. The strength of each may change according to client singularity and wellness requirements (Cox, 1982).

The patient’s knowledge of health information can be used to create goals, reduce negative arousal, and provide feedback of one’s sense of proficiency and autonomy. Affective support refers to tending to the patient’s level of emotional arousal; meeting the patient at an equivalent intensity of emotional arousal (Cox, 1982). Decisional control increases the patient’s sense of power over process, encouraging the patient to participate in better health care behaviors. All interventions must be directed at providing the client with information that will develop a more accurate perception of the need, reducing their anxiety and increasing client control over their health care problem (Cox, 1982). Professional-technical competencies, the fourth competency of the client-professional interaction, focus on the client who depends on technical skills of the clinician. The greater the dependence the client has on the skills of the clinician, the less power the client feels over their health decisions and as that dependence decrease, the better the client feels about their contributions to their current care and overall health outcomes (Cox, 1982).

Health outcomes are based on the utilization of health care services, clinical health status indicators, severity of health problems, adherence to the recommended care regimen and satisfaction with care. The significance of the patient’s perception of autonomy of health care and their relationship with the clinician plays a part in how the patient will use the learned information (Cox, 1982).

The IMCHB is a tool which can be used to guide nursing practice as well as research. It can be used to substantiate the role of the advance practice nurse and the impact of professional intervention. With the growth and the increase of the nursing functionality and responsibility, the professional can now help lead the investigation of client behavior and professional intervention in the prevention of chronic disease and promotion of health (Cox, 1982).

Review of the Literature

The research for this literature review was conducted utilizing academic search engines and textbooks, in addition to medical, government, and professional organizational websites. All articles were retrieved from the search engines Medline, Galileo, CINHAL, and Google Scholar. Additional information was retrieved in various formats from American Heart Association (AHA), Centers for Disease Control (CDC), National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), National Institute of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Primary Care Progress (PCP), and World Health Organization (WHO). The keywords metabolic syndrome, atypical anti-psychotics, schizophrenia, evidence-based treatment, treatment barriers, mental health, mental illness, recognition and treatment, advance practice nurse, and population at risk were used in efforts to retrieve only the most relevant information necessary for the construction of an effective evidence-based teaching project and peer-reviewed, scholarly written thesis paper. Limiters were placed to allow the retrieval of professional, educational, organizational, and peer-reviewed information, constructed within a five year timeframe (2012 to present). After extensive searches via these requirements proved insufficient for my research in whole, it was necessary to elicit and utilize information dating back to 1982.

Research Utilizing the IMCHB Model

Cox’s Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior (IMCHB) was employed to direct an organized and comprehensive description of community-based elders. The abstract, concepts, constructs, factors, and variables described by one component of the model were able to account for greater than 50% of the difference of the elders’ health status and more than 45% of the difference in their well-being. The model highlighted and brought to the forefront understandable and comprehensible demographic, communal, and health profiles identifying those at risk for decreased health, wellbeing, and self-care potential. The IMCHB proved to be a positive and functional framework with which to create and launch a practical foundation on which nursing interventions could be developed (Cox, 1986).

Cox’s IMCHB was used in a weight control program for enlisted U. S. Army soldiers. Associations of client singularity variables to one another and to pre-intervention measures of client outcomes were studied in a sample of approximately 150 enlisted men. Concepts obtained from the framework were tested using several regressions or changing variables (Troumbley & Lenz, 1992). Cox’s model received incomplete support, as some client singularity variables were interrelated, explaining some variances in health status, but very little differences in health risk. Demographic characteristic were not completely effective predictors in this experimental program, however, it is noted and agreed upon that this framework had indeed demonstrated potential usefulness in offering baseline information for preventive health programs in work-related settings (Troumbley & Lenz, 1992).

In a 1984 study by Cox and Roghmann, the common concepts, variables, and relationships explained by the IMCHB were used to guide a secondary statistics investigation of a woman’s decision to request an amniocentesis. Step-wise multiple regressions clarified more than 58% of the difference in the patient’s decisions by examining the factors which identifies the patients individually as unique per their reactions to at-risk pregnancies and descriptions of patient-provider interactions. The study concluded that while the relationships proposed in the model need additional realistic evaluation, this first application effectively demonstrated the testability of the IMCHB and its potential to direct nursing investigations (Cox & Roghmann, 1984).

Lastly, the IMCHB framework was compared with other models, tested, and offered as a guide for practice in medical settings where the boundaries between medicine and nursing were considered distorted, vague and unclear (Mathews, Secrest, & Muirhead, 2008). The IMCHB was concluded to be a nursing model which observes and scrutinizes the essentials of patient individuality; incorporating the knowledge and skills of the advance practice nurse with the understanding and accountability of the client to utilize appropriate interventions to increase the positive changes in the outcome of their healthcare. This model further concludes as broad enough to cover the scope of advance practice, yet specific enough to provide role clarity and a basis upon which to guide the nursing process for positive health outcomes (Mathews, Secrest, & Muirhead, 2008). This framework assists to validate the assumption that the clinicians who observe the patient as a multifaceted unique individual and establishes a therapeutic nurse-client relationship, have a greater impact on the creation of positive patient health outcomes (Mathews, Secrest, & Muirhead, 2008).

Relevant Research Related to the Topic

The literary search concluded multiple research studies related to schizophrenia, atypical antipsychotics, metabolic syndrome, and the need for improved and proficient monitoring in the primary care setting. Henry Nasrallah (2012) suggests that patients with schizophrenia are compromised both physically and mentally, relying on the compassion and commitment of the medical professional to supply and provide the necessary treatment for them to lead normal existences (Nasrallah, 2012). Dr. Nasrallah further stated that both physicians and nurse practitioners are aware of the issues facing schizophrenic patients on atypical antipsychotics, but inconsistent monitoring was ongoing (Nasrallah, 2012). In 2013, Owen et al. performed a randomized trial testing the effectiveness of an evidence-based quality improvement plus facilitation intervention. This study investigated the effects of monitoring and management of metabolic side effects on 300 patients taking antipsychotics via 12 sites: six intervention sites and six control sites, over a six-month time frame. The interventions used in this study concluded that effective and timely monitoring and management would produce improved patient safety and long-term outcomes (Owen, et al., 2013).

Theophilos, Green, and Cashin, (2015) researched a Californian case study on nurse practitioner mental health care in the primary care setting to evaluate what approaches are needed to address health disparities facing patients without access to specialized care centers and clinicians. This study concluded that because of the limited access to specially educated psychiatric and mental health nurse practitioners and an adequate availability of primary care nurse practitioners in the research area, the services rendered in primary care needs to involve a holistic approach which includes mental health care services (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). These researchers also suggested per this study that because in many instances primary care nurse practitioners are the only treatment providers available, the treatment necessitates moving beyond screening to the initiation of an intervention, and the nurse practitioner’s educational curriculum should include proficiency in mental health (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). A study performed by Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, and Bellomo in 2015 on the proposed reduction of life expectancy of schizophrenic patients as a result of antipsychotic treatment conducted a study on the link between cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and the use of atypical antipsychotics. The authors researched multiple articles about schizophrenic patients, evaluating the many cardiovascular and metabolic anomalies experienced by schizophrenic patients being treated with atypical antipsychotic medications. The study concluded that the metabolic consequences experienced by schizophrenic patients taking antipsychotic medications significantly increased their risks of mortality, and many of the factors placing them at risk were highly preventable (Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, & Bellomo, 2015). This study further concluded that it is extremely essential for all primary care nurse practitioners encountering these patients to utilize international guidelines and preventative procedures to screen and monitor for the co-morbid conditions associated with antipsychotic use to reduce the mortality rates and improve the health outcomes of schizophrenic patients (Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, & Bellomo, 2015).

Mental Illness

Mental illnesses are health conditions concerning changes in thinking, emotion or behavior, alone or in combination, associated with distress and/or problems functioning in societal, employment or family activities (Parekh, 2015). Mental illness refers to a wide range of mental health conditions and disorders affecting your mood, thinking and performance (Mayo Clinic, 2015). Mental illnesses, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) are diseases of the brain. They are described in very broad terms encircling a long list of illnesses. Before a definitive diagnosis of mental illness can be made, a list of key principles must be met. Mental illnesses are believed to be caused by a variety of genetic and environmental factors. It is thought to be the result of inherited traits, environmental exposures before birth, and/or brain chemistry (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe mental disorder affecting how one thinks, feels and acts. People with schizophrenia may behave as if there is a disconnected or dysfunctional reality (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). Schizophrenia interferes with an individual’s ability to think clearly, manage emotions, make rational decisions, and communicate with others (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). Although schizophrenia is not as common as other mental disorders, its symptoms can be equally or more disabling than other disorders of its kind (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016).

The three categories describing the symptoms of schizophrenia are positive, negative, and cognitive. Positive symptoms are psychotic behaviors not generally seen in healthy people. Patients exhibiting positive symptoms show signs of a disorganized and distorted reality. These symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, thought disorders, and movement disorders (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). Negative symptoms are associated with disruptions to normal emotions and behaviors. They include flat affect, reduced feelings of pleasure in everyday life, difficulty beginning and sustaining activities, and reduced speaking (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). Cognitive symptoms are complex in that they are more subtle for some patients, and severe for others. These symptoms involve changes in memory and other areas of thinking. They include poor executive functioning, issues with focusing or paying attention, and problems with using information immediately after learning it (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016).

Patients with schizophrenia are 2 to 2.5 times more likely to die earlier than the general population. This is most often linked to physical illnesses, such as cardiovascular, metabolic and infectious diseases (World Health Organization, 2017). The symptoms associated with schizophrenia are usually noted between the ages of 16 and 30. Men often develop symptoms of schizophrenia earlier than women, and people are not typically diagnosed with schizophrenia after age 45 (Medline Plus, 2016). Schizophrenia is not as common as other illnesses of its kind, but affects more than 21 million people worldwide; 12 million in males, 9 million in females, without respect to race and socioeconomic background (World Health Organization, 2017).

Research has not identified one single factor responsible for the cause of schizophrenia. It is thought to have manifested from an interaction between genes and a range of environmental factors including brain chemistry and substance abuse (World Health Organization, 2017 ; National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). Successful diagnosis of schizophrenia consists of the manifestation of two or more of the following symptoms occurring persistently (at least 6 months) in the circumstance of reduced functioning: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). There is no cure for schizophrenia, but it can be successfully treated with atypical antipsychotic medications and psychotherapy (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017).

Atypical antipsychotics. Antipsychotics are medications used to manage and treat schizophrenia disorder; defined as conditions affecting one’s attention, concentration, thoughts, and awareness. Psychosis can be a symptom of a condition such as drug abuse or a mental disorder in itself, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or very severe depression frequently referred to as “psychotic depression” (NIMH, 2016). There are two types of antipsychotic medications, classified as typical and atypical. Typical antipsychotics are older, first generation antipsychotic drugs. Atypical antipsychotics are newer, second generation antipsychotic drugs that have a different chemical structure, giving them different side effects in comparison to the first generation (Purse, 2016).

The second generation “atypical” antipsychotic (AAPs) medications were developed in the 1950’s and launched for use in the late 1990’s. The term “atypical” implies that this generation is unlike its predecessor type class of medication; producing decreased adverse side effects, with the ability to treat both negative and positive signs and symptoms of the same processes (Jibson, 2016). First and second generation antipsychotic drugs are similar in their quantifiable effectiveness, with an exemption of clozapine, a second generation antipsychotic (SGA) with an unrivaled effectiveness in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Antipsychotic drugs have individualized dosing, routes of administration, pharmacokinetics, side effects, and prices; all of which are inclusive dynamics controlling their selection for individual clients (Jibson, 2016).

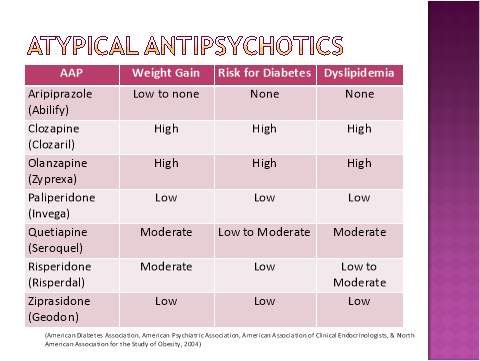

Research now shows that the use of the newer, second generation AAPs have shown a decrease of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) at clinically effective doses in patients being treated for schizophrenia and schizoaffective related illnesses (Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, & Bellomo, 2015). This class of medications also showed a lower ability to causing tardive dyskinesia (TD) with extended management, as well as the ability to treat both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Purse, 2016). All of the aforesaid were huge issues with the use of the older, typical version antipsychotic medications. Some atypical agents currently available and being used to treat psychotic related illnesses include clozapine (Clozaril), risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), ziprasidone (Geodon), aripiprazole (Abilify), and paliperidone (Invega) (NIMH, 2016). Not all AAPs are approved for the treatment of the same conditions (Purse, 2016).

Abilify (aripiprazole) is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat schizophrenia in those 13 years and older. Abilify is used particularly for manic episodes, and often prescribed with a mood stabilizing medication. The two black box warnings related to Abilify are increased rate of death in the elderly population with dementia-related psychosis, and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts in young adults and children when combined with antidepressants (Purse, 2016).

Clozaril (Clozapine; CLZ) is considered the main stay of all AAPs. It belongs to the chemical class of dibenzodiazepines (diazepine heterocycle fused to two benzene rings) and is approved to treat severe, treatment-resistant schizophrenia (Mauri, et al., 2014). It has five potentially serious black box warnings that include a risk of low white blood cell counts, seizures, heart inflammation and fainting related to orthostatic hypotension in addition to an increased risk of death with any use in the elderly patients (Purse, 2016).

Geodon is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia with a noted success during both acute symptoms as well as chronic management (NIMH, 2016). Geodon has less risk of weight gain than some other AAPs, while continuing to work effectively in controlling both positive and negative symptoms (FDA, 2016). Recent statistics showed approximately one in every 4000 patients can develop a heart arrhythmia while using Geodon, so it is suggested that it not be used in patients with a current or history of prolonged QT syndrome, heart failure or a recent heart attack, or those already experiencing an abnormal heart rhythm (Purse, 2016).

Risperdal and Seroquel are both approved to treat schizophrenia. Risperdal is available in both oral and a two week duration injectable form. Seroquel is also approved for the treatment of depression when combined with an antidepressant medication. It is sometimes used in conditions like insomnia, considered an off-label use, as it does not have an FDA approval for that condition (FDA, 2016).

Invega has been FDA-approved to treat schizophrenia in both adults and adolescents and schizoaffective disorder in adults only. Invega is the only oral AAP presently approved to treat schizoaffective disorder. It is additionally available in two injectable versions: a one-month and a three-month duration dose. Its black box warning is related to an increased risk of death in elderly patients (Purse, 2016). Zyprexa is approved in the treatment of patients 13 and older with schizophrenia and weight gain is the side effect most commonly reported by adolescent patients (Purse, 2016).

Atypical antipsychotics are directly associated with potentially serious unfavorable metabolic abnormalities. These include obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and type two diabetes mellitus (Kang & Lee, 2015). These metabolic disturbances can enhance the risk of cardiovascular diseases and premature death. The variance of metabolic side effects with the use of different AAPs strongly suggests that different AAPs are affiliated with different levels of risk for metabolic instability (Kang & Lee, 2015).

Four new second-generation antipsychotics are available: iloperidone, asenapine, lurasidone, and in the very near future cariprazine. Comparable to ziprasidone and aripiprazole, these upcoming agents are projected to have a lower tendency for weight gain and negative metabolic occurrences than previously used second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine or clozapine. Lurasidone is reported the best in this class for reducing problematic changes in body weight and metabolic factors (Mauri, et al., 2014).

Antipsychotic medications are thought to be unique in their usefulness in the treatment of acute psychosis associated to any origin and in the management of the chronic psychotic disorders noted in schizophrenic patients. Choosing an appropriate AAP in the management of schizophrenia and other like disorders, the risks of unavoidably developing metabolic syndrome have to be evaluated against the more urgent risks associated with destructive and aggressive behaviors as they relate to the potential harm of the patient and others (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011).

Mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotics. The principal dissimilarity between typical and atypical, first and second generation antipsychotics has been concluded on experimental and quantifiable clinical findings. Typical antipsychotics are characterized by the adverse side effects of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), hyperprolactinaemia, tardive dyskinesia and most probable neuroleptic malignant syndrome (Mauri, et al., 2014). Atypical antipsychotics are differentiated from first generation, typical antipsychotics because of their lower propensity of development of the same unwanted side effects, by effectiveness and for all purposes presumed improved safety (Mauri, et al., 2014). Research now suggests that the same mechanism by which AAPs are able to control and manage the negative signs of schizophrenia with insignificant side-effects is the same mechanism or process for which it possibly links the patients to metabolic syndrome. The action that makes it most effective is causing the greatest harm (Mauri, et al., 2014).

Both the positive and negative effects of the antipsychotic class of medications depend on the dopamine pathway and receptor occupancy. The dopamine pathway is believed to be the universal target for all antipsychotic drugs, and it is further supposed that no drug has yet been recognized with an antipsychotic action without a considerable similarity for D2 receptors (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014). The proposed method of action for the majority of first and second generation antipsychotics (FGAs and SGAs) has been viewed to be via the post-synaptic blockade of brain dopamine D2 receptors. There are three exceptions, aripiprazole and brexpiprazole, which are D2 receptor partial agonists and cariprazine, which is a D3-preferring D3/D2 receptor partial agonist. Multiple research studies endorse the function of these receptors in the positive action of antipsychotics; most particularly the strong association between D2 receptor binding and clinical strength, along with a steady requirement of 65 percent D2 receptor occupancy for antipsychotic effectiveness in useful imaging studies (Jibson, 2016).

Nearly all SGAs differ from older agents pharmacologically as serotonin 5HT2 receptor binding transcends their attractive force to dopamine D2 receptors, whereas in FGAs this does not commonly occur. Because of the previously stated, 5HT2 activity is considered one explanation for the overall decreased risks and manifestations of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) experienced with the atypical agents in contrast to FGAs (Jibson, 2016). Additional features of SGA pharmacokinetics corresponding with the reduced risk of EPS include loose D2 receptor binding with quick release rates and favorable binding of substances to receptors in the limbic and cortical brain sections instead of the rather than striatum (Jibson, 2016).

All antipsychotics are differentiated by their pharmacological composition via a multi-receptor attraction, essentially interacting with about 16 to 18 receptors of which, including their subtypes, are listed as dopamine, serotonin, cholinergic-muscarinic, adrenergic, histamine (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014). Antipsychotics are diversified in terms of structure. They are equally varied with respect to both their pharmacological and therapeutic properties. Their force of attraction in descending order for the D2 receptors (with the exception of aripiprazole which is agonist/antagonist) are as follows: risperidone, ziprasidone, olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014).

Potential side effects of atypical antipsychotics. Multiple research studies hypothesizes that autonomic nervous system dysfunction, essential to psychotic disorders and powerfully exacerbated by antipsychotic treatment, is the source of the insidious metabolic and vascular dysfunctions associated with psychosis related illnesses (Scigliano & Ronchetti, 2013). The metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics are thought to be mostly effective by their potential to inhibit peripheral dopamine reception, which physiologically transforms sympathetic actions (Scigliano & Ronchetti, 2013). Atypical antipsychotics are known to bind to a variety of non-dopaminergic targets, such as serotonin and histamine receptors, a functionality of weight gain and obesity, proposing that the ability of each antipsychotic to trigger metabolic derangements is a result of their actions on all of the receptor processes involved in maintaining metabolic homeostasis (Scigliano & Ronchetti, 2013).

A receptor involved in weight control is the 5HT6 antagonist which inhibits food intake. Studies revealed that 5HT6 antagonism does not protect against obesity, as antipsychotics with the highest attraction to this receptor, clozapine and olanzapine, showed the highest increase in weight. 5-HT1B/2C agonist mCPP generated a reduction in food intake, perhaps by decreasing neuropeptide Y (NPY) in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, involved in increased food intake and in regulating body weight because of its abundance of 5-HT2C (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014). Increased body weight, a key component of metabolic syndrome, is usually linked to insulin resistance and alterations in plasma glucose and lipid levels. With this, it is critical to be reminded that obesity is not the only contributing factor for many cases of diabetes occurring during antipsychotic treatment (Scigliano & Ronchetti, 2013), and for some, it is complicated to conclude whether the incidence of metabolic disorders is increased independent of antipsychotic treatment or a side effect of medication (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014).

Weight gain is the most recognized metabolic effect, while this varies considerably among atypical antipsychotics: clozapine and olanzapine had the greatest risk, quetiapine and risperidone had a moderate risk, aripiprazole, amisulpride and ziprasidone had the lowest risk, with a negative impact on the compliance to treatment and the perceived quality of life (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014). The presence of abdominal adiposity leads to insulin resistance. Atypical antipsychotics have a strong antihistaminic action, and H1 receptors are interrelated with increased weight gain (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014).

A known effect of obesity and of the metabolic syndrome is the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes can also occur in the absence of obesity in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics producing a potentially lethal ketoacidosis (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014). Studies confirm that two atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine and clozapine) demonstrated the greatest effects on weight gain and impairment of glucose levels, indicating a common pharmacological process (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014). The phenomenon for which atypical antipsychotics are able to cause diabetes is through their ability to block the pancreatic M3 receptor. The glucose attracted acetylcholine cannot trigger the M3 receptor when blocked by antipsychotic use. The plasma level of insulin is inadequate and therefore unable to reduce post-prandal hyperglycemia. Glucose blood levels remain elevated; acetylcholine stimulates a parasympathetic response, releasing insulin by increasing insulin synthesis, which reaches the insulin receptors desensitization and the insulin resistance. Many pancreatic M3 receptors can stimulate insulin secretion and consequently insulin resistance. The lengthened state of hyperglycemia creates a decreased sensitivity to glucose carriers resulting in glucose intolerance (Miron, Baroana, Popescu, & Ionica, 2014).

Metabolic Syndrome

High blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity are all major risk factors for heart disease, and together are classified as metabolic syndrome (CDC, 2015). Rapid weight gain linked to the use of antipsychotic medication in addition to poor physical wellbeing (smoking, sedentary lifestyle) leading to type two diabetes and metabolic syndrome are major sources of morbidity and premature mortality in individuals with schizophrenia and psychosis-related illnesses (NICE, 2013). Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of metabolic risk factors. In the presentation of these risk factors collectively, the propensity for future cardiovascular problems are larger than any individual factor presenting alone (AHA, 2016).

The original use of the term metabolic syndrome (MS) was notably coined by German researchers in late 1970s. Metabolic Syndrome is additionally identified as insulin resistance syndrome and the acronym CHAOS (coronary artery disease, hypertension, adult onset diabetes, obesity and stroke). Metabolic syndrome is fundamentally an assemblage of obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin insensitivity, unbalanced and disturbed glucose metabolism and hypertension (Shah, Nair, Kaira, & De Sousa, 2012).

The group of illnesses associated with metabolic syndrome increases a patient’s risk for heart disease, diabetes and stroke (AHA, 2016). Diagnosing metabolic syndrome requires the patient to be diagnosed with and treated for at least three of the following processes: increased blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels; occurring together increasing the probability of heart disease (Mayo Clinic, 2016). The serious health conditions of metabolic syndrome affects approximately 34 percent of U.S. adults, placing them at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke and other diseases linked to fatty buildups in arterial walls. The exact etiology is unknown; however, the causative factors of metabolic syndrome include obesity, sedentary lifestyle and genetics (AHA, 2016). It is a direct cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with schizophrenia and other psychosis related disorders and has an occurrence rate twice that of populations void of psychiatric illnesses (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011).

Metabolic syndrome promotes an inflammatory process causing injury to the linings of the blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. This is made most obvious by an increased level of the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein (Keller, Sabatino, Windland-Brown, Porter, & Keller, 2015). Metabolic syndrome also promotes a thrombotic process, which is supported by elevations in platelet aggregation, and increased fibrinogen levels (Keller, Sabatino, Windland-Brown, Porter, & Keller, 2015). Obesity is believed to be the most significant contributor of metabolic syndrome. Obesity increases the development of insulin resistance and places the patient at increased risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus (Keller, Sabatino, Windland-Brown, Porter, & Keller, 2015). During the mutations causing hyperglycemia and unbalanced lipid metabolism, peripheral tissues become resistant to insulin. The pancreas over-secretes insulin in a battle to combat tissue resistance, resulting in hyperinsulinemia (Keller, Sabatino, Windland-Brown, Porter, & Keller, 2015).

Because multiple medical and disease focused organizations attempted at concluding a definitive diagnostic criterion for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, the International Diabetic Federation (IDF), American Heart Association (AHA) and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) came together in 2006 to organize an agreeable criterion for the clinical diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. It was, at that time decided that a patient must meet three or more of the five conditions to be definitively diagnosed with metabolic syndrome (International Diabetic Federation, 2006). Also established at that time, because the parameter for central obesity standards continues to be population and country specific, it was additionally recommended until further data is made available, that the IDF parameters be used for non-European patients and either the IDF or AHA/NHLBI parameters be used for patients of European origin (International Diabetic Federation, 2006).

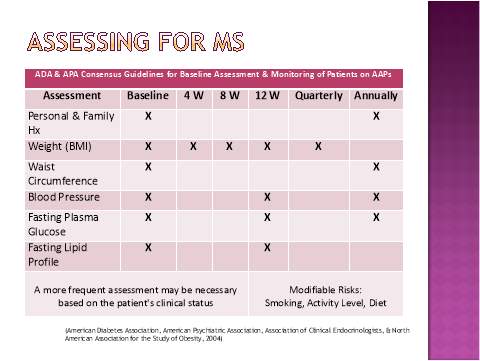

Multiple recent studies suggest that patients with major mental illnesses do not receive sufficient assessment and efficient management of their cardio-metabolic concerns. For effective assessing, monitoring, and management of patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications, it is recommended as the initial step, after diagnosis is to perform a baseline history and physical assessment with a planned schedule for routine follow-up (Cenpatigo Integrated Care, 2016). Personal and family history should be performed at baseline and annually. Patient weight and body mass index should be assessed at baseline and at four, eight, and twelve weeks, then quarterly. Blood pressures, fasting plasma glucose, and fasting lipid profile, should be assessed at baseline, every twelve weeks, annually, then every five years given there are no abnormal findings throughout this process. In the event of abnormal findings, alternate interventions are warranted (Cenpatigo Integrated Care, 2016). These standards were suggested by a group of clinical practitioners formed by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the American Psychiatric Association (APA) & the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, & North American Association for the Study of Obesity, 2004).

An effective collaborative care system between the primary care clinician and the psychiatrist/psychologist is significant for the mentally ill because of their increased impaired ability of appropriate self care (Mangurian, et al., 2013; Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, & Bellomo, 2015). Collaboration of this kind will improve patient monitoring, assist in a more timely recognition of metabolic derangement, and limit repetitive clinical and/or laboratory workup (Mangurian, et al., 2013). Appropriate and situation specific education for the patient, patient family and ancillary care staff enhances disease management, medication compliance, and minimizes adverse metabolic side effects (Theophilos, Green, & Cashin, 2015). Patient teaching should be a continuous practice and be provided in an approach and pace convenient for the patient. Education should envelop topics relative to the patient’s condition and situation (Ventriglio, Gentile, Stella, & Bellomo, 2015). Modifiable risk factors should also be discussed, even in patients free from metabolic abnormalities (AHA, 2016).

The awareness of metabolic complications should encourage clinicians and psychiatrists to screen all patients’ first occurrence of psychosis for the predisposing factors of metabolic syndrome. Once a patient has been prescribed medication, they should be monitored on a regular and continous basis (Bajaj, Varma, Srivastava, & Verma, 2013). Routine blood tests and glucose sensitivity and tolerance, along with the assessment of practical body proportion measurements. Psychiatrists should screen for possible metabolic disturbances if their patients have no known access to primary care (Nasrallah, 2012). All patients seen in any clinical setting should be routinely educated about and provided with information on simple lifestyle recommendations concerning the relationship of a balanced diet and regular exercise, to the primary prevention of disease (Nasrallah, 2012). These interventions are still considered the most effective ways of preventing cardiovascular disease and its related complications (Bajaj, Varma, Srivastava, & Verma, 2013).

The agreement on recommendations for metabolic monitoring of patients treated with atypical antipsychotics has been comprehensively published. Studies show that effective monitoring of the metabolic derangements related to the use of AAPs consists of assessments at baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks, quarterly, annually, and every 5 years for factors such as personal & family history, weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, blood pressure (BP), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and fasting lipid profile. Particularly, this type of supervision advocates the testing of FPG levels (at baseline, 12 weeks, then annually) and a fasting lipid profile (at baseline, 12 weeks, then every 5 years if normal values are consistent).

These recommendations represent a fundamental, but critical standard related to the healthcare of patients with chronic mental illness. All guidelines support a common plan for the evaluation of patients when initiating and maintaining therapy with antipsychotic agents. The recommended plan includes recognition and interventions for both non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors. Non-modifiable risk factors include increasing age, sex (with increased rates of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome in treated female patients); personal and family history of obesity, diabetes, heart disease; and ethnicity (with increased rates of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and coronary heart disease in patients of non-European descent). Modifiable risk factors include obesity, visceral obesity, smoking, physical inactivity, and dietary habits. The impact to which all factors contribute to unwanted side effects and an agreement on changes promoting positive outcomes with follow-up (Riordan, Antonono, & Murphy, 2011).

Summary of the Review of Literature

Methodology

The purpose of this project was to enhance the awareness of the metabolic changes associated with patients taking atypical antipsychotics for the nurse practitioner in primary care. This project was composed with a fundamental intent to augment the knowledge of graduate primary care nurse practitioner students of the increased risks of metabolic syndrome linked to atypical antipsychotic use and its profound impact on the U.S. cardiovascular mortality rate.

Design of the Project

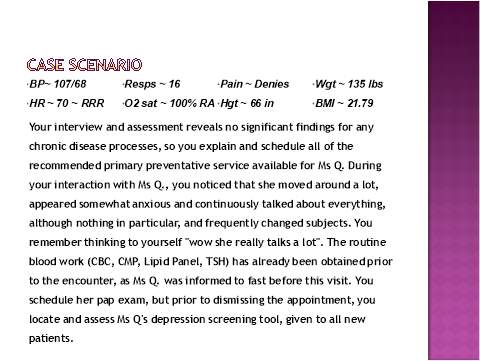

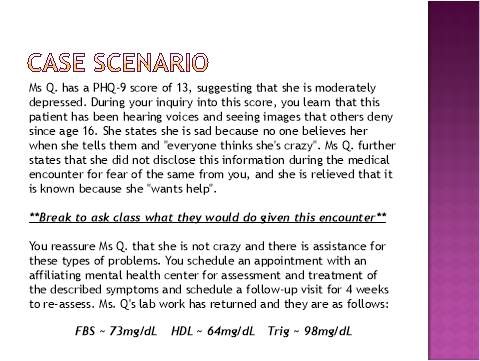

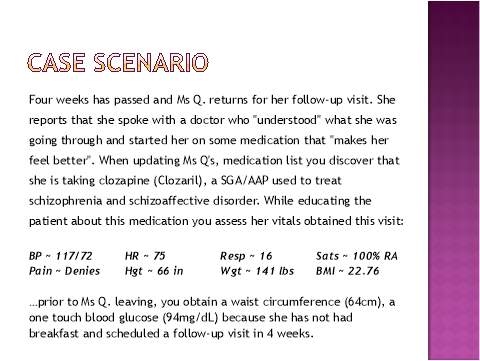

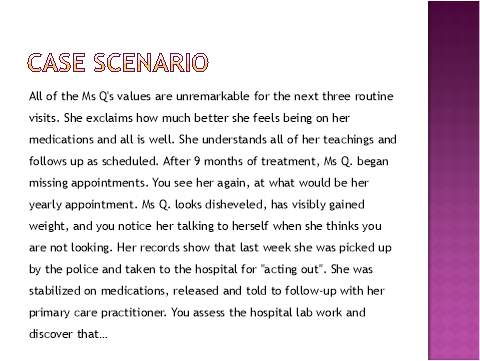

This project was designed to educate nurse practitioner students studying the disease prevention and health promotion aspect of primary care, with the intent to service patients treated with via initiation or maintenance, atypical antipsychotics. The teaching components of this project included an educational PowerPoint presentation and a case study supporting the understanding of the information presented.

PowerPoint® 2016 was used to design the visual presentation and participant handouts (see Appendix A). The plan for this presentation’s visual design was to ensure legibility, message simplification, along with learner engagement and attention to important points. The purpose of this power point presentation was to connect with the learner in a fashion that will assist their perception of the topic, while increasing their ability to process, store and recover the presented information to retrieve it when needed (Pugsley, 2010).

The presentation slides were designed using standardized position, colors, and styles as recommended by the National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL) (2016). The presentation slides were designed using black fonts on a white background, taking into consideration the possibility of colorblind audience members, as well as not to confuse the importance of the information being presented with the design of the content. A humanist sans-serif, greater than 25 point Trebuchet MS font was used, allowing the information to be more easily read from a distance. The font style was limited to bold and standard to clarify rather than confuse the information being delivered (Pugsley, 2010). Additionally, all of the aforementioned was chosen to enhance readability from all locations and angles of the room, assuring a visual aid that will express the desired educational information necessary to engage the target audience (NCSL, 2016).

The PowerPoint presentation information focused on the education and impact of, as well as the importance of recognizing the signs and symptoms of metabolic syndrome in patients taking atypical antipsychotics for advanced practice nurses providing preventative, holistic, patient-centered care in the primary care setting. The presentation included educational information on atypical antipsychotics, the commonness and rationales for their use and side effects related to their usage. Metabolic syndrome, its prevalence, contribution and impact on the U.S. cardiovascular mortality rate, economy, preventative, and health promotion services of primary care was also included in the presenting information. Additionally included was evidence-based information on recognizing the signs of metabolic syndrome in patients that may present in the primary care setting, as well as information assisting the clinician in educating the patients taking AAPs with the tools necessary to make better lifestyle choices, preventing a problem before it starts.

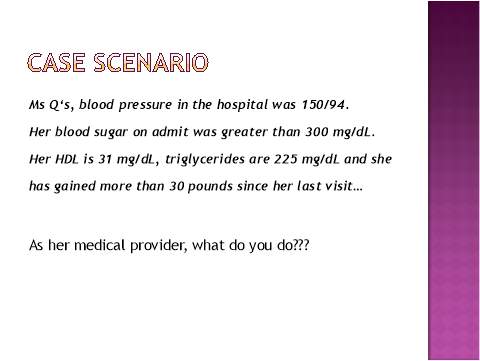

Because it was suggested that adults learn best when the subject is relatable and instantaneously applicable (Groleau, 2005), a case study was used to give the adult audience the opportunity to apply the newly discussed concepts to a problem based scenario (Mindtools, 2016). The case study provided a useful tool for the adult learners to utilize critical thinking, while analyzing the presented situation and building a more relatable foundation for high quality learning that they will maintain long-term (Mindtools, 2016). Incorporating a case study into the teaching presentation was decided to enhance audience participation and evaluate the understanding of the presented information (Mindtools, 2016).

Project Participants

Because this project emphasized the importance of recognizing a problem before it becomes life threatening and life altering for the patients being serviced by nurse practitioners in the primary care setting, the target audience for this project was graduate students currently enrolled in advanced health assessment at a university located in the southeastern United States. There were a total of 18 students in attendance for the presentation.

Implementation

The teaching portion of this project was conducted in a classroom setting at a university in southeastern United States during the spring semester of 2017. The visual component of this presentation required the use of a computer and a projector to play and view the information provided via PowerPoint. The case study was covered at the end of the PowerPoint presentation; and made available at that time to ensure opportunity to complete and participate in group discussion for fairness to all.

All attendees were offered a keepsake topic titled bag with contents which would remind them to assess, monitor for, and recognize the signs of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenic patients taking atypical antipsychotics that they may encounter in their future practice. The contents of the keepsake topic titled bag included ink pens in the shapes of a nurse, hypodermic needle, and pill. There was a topic titled notepad, and a pill shaped blank note included in the handout bag. Also included in the handout bag were three shaded laminated cards detailing the signs of metabolic syndrome, how to assess for metabolic syndrome, and the medications that are frequently prescribed for schizophrenia causing metabolic syndrome (see Appendix B).

Evaluation

At the presentation’s conclusion, a questionnaire was given to each attendee requesting completion and feedback on their perspectives of the presentation. The questionnaire addressed and questioned all aspects of the event. No demographic data was requested or needed. The questionnaires were completed in a confidential manner, and the attendees were asked to return their completed questionnaires face down at the end of the row of tables prior to exiting the event.

The questionnaire was developed utilizing the five point Likert scale for evaluation (see Appendix C). There were evaluating statements listed to elicit one of five responses of strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree, ranking 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 correspondingly. The questionnaire addressed and requested feedback responses for all aspects of the event. Included was space for feedback on the visual content, hand-outs, reference material, information presented and case study content, their usage related to the topic, and overall choreography. Feedback on the presenter, their knowledge and enthusiasm of the topic presented, as well as the overall atmosphere of the chosen setting, was requested for critique in the provided questionnaire. Lastly, the questionnaire included space for additional information the attendee may have possibly wanted to share or augment upon, with an allotted section for written feedback, opinions, and comments.

Results

A total score of 50 would be indicative of an overall evaluation of “strongly agree” for clarity/organizational, understanding of the presented information, relevance to practice, presenters response to inquiry, engagement and time effectiveness of presentation. Of the 18 attendees attending the presentation, 11 attendees (61 percent) reported an overall score of 50. Seven of the 18 attendees (39 percent) reported scores between 42 and 49. All attendees agreed that the presentation gave them a better understanding of the problem and the information presented was relevant to advanced practice nursing.

Conclusion

The knowledge of metabolic complications should hearten and promote all practitioners to screen all patients under their care for the negative side effects of metabolic syndrome in their quest to combat the mortality rates of cardiovascular disease. This intervention should also be performed as standard in our journey to assist in the wellness and prevention of harm for the patients we elected to treat. After the prescription of any medication, regardless of the disease process for which it is prescribed, it is the direct duty of the clinician caring for the patient to monitor for any effects preventing the intended outcome of the prescription. It is further a duty of the practitioner to ensure that no intended harm is allowed via prescribed interventions. This is the case as well, with the manifestation of metabolic changes in patients being treated with the most favorably prescribed, and most effectively resulted atypical antipsychotics. Research has shown that this need is not currently being proficiently fulfilled, by the people most equipped to handle the problem.

Multiple research studies, including those performed on physicians and nurse practitioners, suggest that prescribing physicians and screening advanced practice nurses combine their formally trained knowledge and assist each other’s segment of care in the promotion of wellness to the patient. It is acknowledged, approved, and evidence-based confirmed that monitoring and intervening of negative manifestations exhibited by schizophrenic patients treated with atypical antipsychotics could decrease morbidity and mortality. It is further proven that all clinicians working as a team in standard patient care produces the better of all possible outcomes for the patient.

The overall focus of this project was to educate the upcoming nurse practitioners of the aforementioned. The plan was to inform the primary care candidates that these desperately needed interventions are not currently being carried out in the practice of which they are planning to be employed, and provide evidence-based information on how to correct the issue during their practice. The presentation and handouts were implemented to facilitate this focus. The conclusion is drawn from the overall information investigated, identified, and recommended via the literary research, all in efforts to promote a more proficient, patient-centered, optimal care experience for the schizophrenic patient taking atypical antipsychotics.

References

American Heart Association [AHA]. (2016). About metabolic syndrome. Retrieved from: https://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/MetabolicSyndrome/About-Metabolic-Syndrome_UCM_301920_Article.jsp

Bajaj, S., Varma, A., Srivastava, A., & Verma, A. K. (2013). Association of metabolic syndrome with schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism , 17 (5), 890-895.

Burghardt, K. J., & Ellingrod, V. L. (2013). Detection of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia and implications for antipsychotic therapy: Is there a role for folate? Molecular Daignosis & Therapy , 17, 21-30.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2013). Burden of mental illness. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics/burden.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2015). Heart disease facts. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2014). Morbidity and mortality weekly report: QuickStats: Percentage of mental health-related primary care office visits, by age group – National ambulatory medical care survey, United States, 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6347a6.htm

Cenpatigo Integrated Care. (2016). Practice guidelines: Metabolic syndrome: Evaluation, monitoring, and recommended interventions. Retrieved from: https://www.cenpaticointegratedcareaz.com/content/dam/centene/cenpaticoaz/Documents/Metabolic%20Syndrome%20Practice%20Guideline.pdf

Corell, C. U., Robinson, D. G., Schooler, N. R., Brunette, M. F., Mueser, K. T., Rosenheck, R. A., et al. (2014). Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) Psychiatry , 71 (12), 1350-1363.

Cox, C. L. (1982). An interaction model of client health behavior: Theoretical prescription for nursing. Advances in Nursing Science , 5, 41-56.

Cox, C. L. (1986). The interaction model of client health behavior: Application to the study of community-based elders. Advances in Nursing Science , 9 (1), 40-57.

Cox, C. L., & Roghmann, K. J. (1984). Empirical test of the interaction model of client health behavior. Research in Nursing & Health , 7 (4), 275-285.

Demirel, A., Demirel, O. F., & Ugur, M. (2015). Atypical antipsychotics induced metabolic syndrome. Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar – Current Approaches in Psychiatry , 7 (1), 81-97.

Ervin, R. B. (2009). Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003-2006. National Health Statistics Reports , 8.

Flynn, M., Houtjes, W., Merks, A., Mierlo, A. V., & Van De Wetering, B. (2015). Metabolic syndrome in mental health and addiction treatment: A quantitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing , 22, 15-19.

Freundlich, N. (2013). Primary care: Our first line of defense. Retrieved from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/health-reform-and-you/primary-care-our-first-line-of-defense

Graham, L. J. (2015). Integration of the interaction model of client health behavior and transactional model of stress and coping as a tool for understanding retention in HIV care across the lifespan. Journal of the Association os Nurses in AIDS Care , 26 (2), 100-109.

Groleau, D. G. (2005). Andragogy in action: Integrating adult learning theory and methods into training design and delivery. Retrieved from: http://www.umsl.edu/~henschkej/andragogy_articles_added_04_06/groleau_Andragogy_in_Action.pdf

Hasnain, M., Vieweg, W. V., Fredrickson, S. K., Betty-Brooks, M., Fernandez, A., & Pandurangi, A. K. (2008). Clinical monitoring and management of the metabolic syndrome in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications. Primary Care Diabetes , 11.

Health Resources & Services Administration. (2013). Projecting the supply and demand for primary care practitioners through 2020. Retrieved from: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/health-workforce-analysis/primary-care-2020

Hoffman, E. L., VonWald, T., & Hansen, K. (2015). The metabolic syndrome. South Dakota Medicine Special Edition , 24-28.

Jibson, M. D. (2016). Second-generation antipsychotic medications: Pharmacology, administration, and side effects. Retrieved from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/second-generation-antipsychotic-medications-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects

Kang, S. H., & Lee, J. (2015). Metabolic disturbances independent of body mass in patents with schizophrenia taking atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatry Investigation , 242-248.

Keller, K. B., Sabatino, D., Windland-Brown, J. E., Porter, B. O., & Keller, M. B. (2015). Cardiovascular problems: Metabolic syndrome. In L. M. Dunphy, J. E. Winland-Brown, B. O. Porter, & D. J. Thomas, Primary Care: The Art and Science of Advanced Practice Nursing (4th ed., pp. 430-503). Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis.

Mangurian, C., Giwa, F., Shumway, M., Fuentes-Afflick, E., Perez-Stable, E. J., Dilley, J. W., et al. (2013). Primary care providers’ view on metabolic monitoring of outpatients taking antipsychotic medication. Psychiatric Services , 64 (6), 597-599.

Mathews, S. K., Secrest, J., & Muirhead, L. (2008). The interaction model of client health behavior: A model for advanced practice nurses. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners , 20 (8), 415-422.

Mauri, M. C., Paletta, S., Maffini, M., Colasanti, A., Dragogna, F., Di Pace, C., et al. (2014). Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: An update. Experimental and Clinical Sciences, International Online Journal for Advances in Science , 13, 1163-1191.

Mayo Clinic. (2016). Metabolic syndrome: Overview. Retrieved from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/metabolic-syndrome/home/ovc-20197517

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2015). Diseases and conditions: Mental illness. Retrieved from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mental-illness/basics/definition/con-20033813

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2015). Diseases and conditions: Mental illness causes. Retrieved from: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mental-illness/basics/causes/con-20033813

Medline Plus. (2016). Schizophrenia. Retrieved from: https://medlineplus.gov/schizophrenia.html

Mindtools. (2016). Case study-based learning: Enhancing learning through immediate application. Retrieved from: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newISS_94.htm

Miron, I. C., Baroana, V. C., Popescu, F., & Ionica, F. (2014). Pharmacological mechanisms underlying the association of atipsychotics with metabolic disorders. Current Health Sciences Journal , 40 (1), 12-17.

Mittal, D., Li, C., Williams, J. S., Viverito, K., Landes, R. D., & Owen, R. R. (2013). Monitoring veterans for metabolic side effects when prescribing antipsychotics. Psychiatric Services , 64 (1), 28-35.

Mozaffarian, D., Benjamin, E. J., Go, A. S., Arnett, D. K., Blaha, M., Cushman, M., et al. (2016). AHA statistical update: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation , 133 (4).

Nasrallah, H. A. (2012). Why are metabolic monitoring guidelines being ignored? Current Psychiatry , 11 (12), p. 2.

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2017). Schizophrenia. Retrieved from: http://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Schizophrenia

National Conference of state Legislatures [NCSL]. (2016). Tips for making effective powerpoint presentations. Retrieved from: http://www.ncsl.org/legislators-staff/legislative-staff/legislative-staff-coordinating-committee/tips-for-making-effective-powerpoint-presentations.aspx#color

National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Schizophrenia. Retrieved from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI]. (2016). What is metabolic syndrome? Retrieved from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ms

National Institute for Health Care Excellence [NICE]. (2013). Psychosis and schizophrenia: Individual research recommendation details. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/researchrecommendation/what-is-the-most-effective-management-strategy-for-preventing-the-development-of-excessive-weight-gain-and-metabolic-syndrome-associated-with-the-use-of-antipsychotic-medication-in-children-and-young-people

National Instute of Health [NIH]. (2016). How is metabolic treated? Retrieved from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ms/treatment

National Institute on Mental Health [NIMH]. (2016). Mental health medications: Antipsychotics. Retrieved from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications/index.shtml#part_149866

National Institute on Mental Health [NIMH]. (2009). Schizophrenia. Retrieved from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/schizophrenia.shtml

Olfson, M., Gerhard, T., Huang, C., Crystal, S., & Stroup, T. S. (2015). Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Psychiatry , 72 (12), 1172-1181.

Olsen, D. (2014). Integrating primary care and mental health key to improving patient care, lowering costs: Primary care physicians play important role in detecting mental, behavioral health issues. Retrieved from: http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/content/tags/affordable-care-act/integrating-primary-care-and-mental-health-key-im?page=full

Owen, R. R., Drummond, K. L., Viverito, K. M., Marchant, K., Pope, S. K., Smith, J. L., et al. (2013). Monitoring and managing metabolic effects of antipsychotics: A cluster randomized trial of an intervention combining evidence-based quality improvement and external facilitation. Implementation Science , 8 (1), 12.

Parekh, R. (2015). What is mental illness. Retrieved from: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness

Primary Care Progress [PCP]. (2016). The issue. Retrieved from: http://www.primarycareprogress.org/learn/the-issue

Preidt, R. (2015). Schizophrenics face much higher early death risk. Retrieved: http://www.webmd.com/schizophrenia/news/20151028/people-with-schizophrenia-face-much-higher-risk-of-early-death

Pugsley. (2010). How to design an effective PowerPoint presentation. Education for Primary Care , 21, 51-53.

Purse, M. (2016). What are atypical antipsychotics? What do they treat? Retrieved from: https://www.verywell.com/atypical-antipsychotics-379663

Riordan, H. J., Antonono, P., & Murphy, M. F. (2011). Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Risk factors, monitoring, and healthcare implications. American Health and Drug Benefits , 4 (5), 292-302.

Scigliano, G., & Ronchetti, G. (2013). Antipsychotic-induced metabolic and cardiovascular side effects in schizophrenia: A novel mechanistic hypothesis. CNS Drugs , 27 (4), 249-257.

Shah, A., Nair, D., Kaira, G., & De Sousa, A. (2012). Metabolic syndrome and antipsychotic drugs-A review. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences , 9 (2), 53-61.

Theophilos, T., Green, R., & Cashin, A. (2015). Nurse Practitioner mental health care in the primary context: A Californian case study. Healthcare (3), 162-171.

Thomas, A. C., Crabtree, M. K., Delaney, K. R., Dumas, M. A., Kleinpell, R., Logsdon, M. C., et al. (2012). Nurse practitioner core competencies. The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties, p. 7.

Troumbley, P. F., & Lenz, E. R. (1992). Application of Cox’s interaction model of client health behavior in a weight control program for military personnel: A preintervention baseline. Advances in Nursing Science .

van Zwieten, P. A. (2006). The metabolic syndrome: Background and treatment. Netherlands Heart Journal , 14 (9), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2557292/.