Deregulation of Local Planning Authority's Control and Regulation of the Conversion of Offices to Residential Use

Info: 10823 words (43 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

Tagged: PropertyConstruction Law

1. Introduction

1.1 Deregulation of planning functions

In 2014 the Government at that time undertook a consultation of the relevant interested bodies and parties as part of its ‘Technical Consultation on Planning’, this consultation set out a host of ideas and reforms to Planning Legislation, that they wished to introduce, to reduce the ‘red tape’ faced by developers and property owners, providing a greater degree of options available to suit their needs and the changing needs of the market. Ultimately, the reforms proposed were intended to re-vitalise the high street, and deliver an increased amount of housing to the market. This was to be done via:

- Permitting the permanent right to allow offices under the B1 use class to be converted to residential units;

- Removing the previous exemptions for previously considered strategically important locations;

1.2 The Permitted Development Right & New Regulations

The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) (Amendment) Order 2016 (the 2016 Order) was revealed, and came into force on the 6th April 2016 amending the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015.

This 2016 amendment order provides for some of the matters that were consulted on as part of the 2014 consultation exercise, and most importantly, provided a means for the permanent change of use of offices to residential conversions without requiring the express consent of the Local Planning Authority. However, it did provided the Local Planning Authority to be notified via an established prior approval mechanism that allowed the Local Planning Authority the ability to consider the appropriateness of the application under specific factors relation to flooding, highways, transport and contamination impacts.

The Government did undertake to retain the existing exemptions to this permitted development right for the areas that the government considered to be ‘strategically important’. Ministers undertook to provide exemptions for 33 areas, across 17 local authorities, following concerns regarding the potential adverse impact the loss of offices could have on the employment opportunities of the area. These exemptions were across varying area nationally, including large part of inner London.

1.3 Project Aims:

The primary project aim is to explore whether the Governments attempt to address the national housing shortfall through the permanent de-regulation of the ability of Local Planning Authorities to control the ad-hoc change of use of offices to dwellings, will have a positive impact on places outside of the major UK cities, where significant property market difficulties, low land values and deprivation exists, without any strategic plans, and wider strategic regeneration. The project will examine statistical and legislative analysis, as well as the use of a case study within Middlesbrough, The project will also examine Manchester as an exemplar example of the success of adaptive reuse of buildings to residential uses when it is part of a wider strategic regeneration, in contrast to Middlesbrough that has suffered from similar socio-economic issues to that of Manchester prior to the regeneration, but now experiencing the ad-hoc conversion of buildings without any strategic implementation.

A secondary aim also seeks to examine the architectural constraints of adapting offices to residential uses, and whether the building actually lend themselves to adaption, and whether they are place where people will want to live. This will be done through the examination of existing academic research, and will aim to examine whether the changes to the permitted development rights will actually influence the conversions or whether there are more significant factors barriers preventing the conversion of these buildings, as opposed to the Planning system.

The tertiary and final lesser aim will examine the interplay of power and control in relation the Government, examining how the deregulation of control by Local Planning Authorities in allowing the unimpeded conversion of offices to dwellings, impacts or feeds into the Governments localism aims and agenda, and the Local Plans adopted by Local Authorities.

1.4 Project Objectives:

- How will the deregulation apply in small regional towns like Middlesbrough?

- What are the barriers and drivers to conversion of offices?

- How (if at all) will the deregulation of power aid the overall housing shortfall in small regional towns outside of the major cities of the UK?

- Will the deregulation of land use based control, lead to future issues for occupants and strategic policy making?

- How this deregulation is perceived, and what perceived impact does it have on the Governments localism agenda?

1.5 Dissertation Structure

1.6 Data collection and analysis methodology

The primary data collection will be obtained using a combined approached interview with persons identified through the data sampling. These interviews are envisaged to be undertaken using a combination of the standardized open-ended interview questions to ensure that the key information requirements are obtained within the same manner to ensure that the responses provided are not elicited through the way in which the question was raised. This will allow for a more rigorous evaluation and analysis of the responses, whilst minimizing variation. The use of standardized questions will also ensure that the most relevant information is obtained from the interviewees within the pressures of limited time permitted for the interviews which will inevitably be present with busy professionals.

The weakness of standardized questions according to Patton is “…that it does not permit the interviewer to pursue topics or issues that were not anticipated when the interview was written. Moreover, a structured interview reduces the extent to which individual differences can be queried.” (2002, p347). Therefore in order to overcome this issue it is intended to complement the standardized questions with an interview guide approach. This complementary approach of using a interview guide will allow the interview to be tailored to each interviewee to ensure that the information obtained can also follow the natural and fluid nature that may elicit new data.

Secondary data will be obtained through qualitative discourse content analysis of Government policy and rhetoric to identify the language being used, why it is being used and to understand the context within which it is being used full conceptualise and understand the issue. It is intended that as part of the analysis of this secondary policy data the following question will be asked of the data:

- What is this discourse doing?

- How is this discourse constructed to make this happen

- What resources are available to perform this activity?

(Potter 2004, pg.609, cited in Bryman 2008)

Data analysis

The data analysis for the overall data will be undertaken within thematic analysis methodology, particularly using inductive and deductive analysis to look for patterns in the data, along with discourse analysis to understand the data uncovered from the interview and the interviewees position and influences. It is intended to classify the data along with the findings of the study within an analytical framework that will have been set from the data recovered.

The introduction of the permitted development right which this project bases itself upon, has only been in full operation since April 2015. Therefore, it is unknown at this stage how, or whether there has been any ‘take-up’ of this right by developers within the two local authority’s being used as cases studies for this project. Therefore, there may be the requirement to look at other regions and local authorities to carry out this study.

There is a risk of a lack of co-operation from the intended interviewee groups. However, as the researcher has been operating within the town planning field for over 10 years, it is hoped that there will be sufficient working relationships to secure the necessary interviews with the appropriate persons. To that degree, the researcher has already secured the agreement of planning professionals within both case study authority’s to undertake interviews.

An additional risk is that currently working within the town planning field the researcher may harbor either subliminal bias towards the subject matter. However, it is considered that the use of combined approach to interviews including standardized open questions as well as an interview guide, will minimize the potential for bias.

There is a finally a risk that the Government may alter or revoke the permitted development rights prior to the completion of the study. However, as this is a very recent piece of legislation it is not envisaged that this will be altered within the next 18 months.

Whist the basis of this project does not propose to undertake any investigations into, or collected data with any vulnerable groups, nor will it be dealing with commercially sensitive information; Rather the project will be concentrating on the personal and professional opinions of professionals, and community groups. It is essential that all information supplied, is done so, in the full knowledge of its purpose. This will be done through an informed consent of all participants, within which they will be made aware of the intended purpose of the information supplied and that they are able to withdraw from the project at any time prior to publication.

The participant’s information and identities is to be kept confidential at all time, in order to protect their personal and professional interests.

It is also intended to offer participants the opportunity to view their contributions towards the finalised document prior to publication in order that will have a final opportunity to withdraw from the project, to remove any risk or suggestion of coercion or pressure to partake or supply information.

2.0 Housing crisis

2.1 How did we get here?

The United Kingdom as island nation, only has a finite supply of available land for housing provision, it is suggest by Kelly (2008) that by the year 2050, 87% of the buildings required within the UK will have already been built, and therefore the pressures for available land will inevitably lead to the adaptive reuse of existing buildings to meet the housing demands and need requirements of the future populations within the UK.

Whilst there is no definitive definition of housing ‘need’ and ‘demand’. The Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) attempted within a research paper ‘Estimating housing need’ (2010) did provide some broad definitions to assist in the purpose of that study. The DCLG defined ‘need’ as being “…shortfalls from certain normative standards of adequate accommodation…” and ‘demand as being “…the quantity and quality of housing which households will choose to occupy given their preferences and ability to pay (at given prices).” (2010, p25).

The Holmans (2013) on behalf of the Town and Country Planning Association published an unofficial report into the housing need and demand within England between 2011 and 2031. This report, whilst unofficial was based on official household interim projection statistics from the Office of National Statistics and estimated between 240,000 and 245,000 additional homes would be required per annum up to 2031 in order to meet new demand and need in England. Whereas in contrast a total of only 107,820 permanent dwelling were completed in England in 2012/13, a shortfall of approximately 132,000 dwellings against the lowest need estimate.

However, this is not the first time that the issue of a housing gap has been raised. In April 2003 the Chancellor and Deputy Prime Minister commissioned a review to be undertaken into the state of the British housing supply. The review was undertaken by Kate Barker, with the finialised report Review of Housing Supply (Barker, 2004) having been published in March 2004.

This review highlighted a number of key findings into the British housing market. It particularly made reference to the intrinsic link between housing supply and the economy stating “A weak supply of housing contributes to macroeconomic instability and hinders labour market flexibility, constraining economic growth. These risks to stability are likely to be increased should the UK decide to join Economic and Monetary Union. The UK should have a more flexible housing market.” (Barker, 2004, p1). Barker went on to detail the housing shortfall within the UK, identifying that “…based on demographic projections. An increase in supply of social housing of 17,000 homes each year is believed to be required to meet the needs among the flow of new households.” (Barker, 2004, p5) and “If the backlog of those whose need has not been met in the past is to be reduced, then up to 23,000 further houses would need to be supplied…” (Barker, 2004, p8).

Successive Governments have sought to address the issues of housing shortfall. Leading to the latest attempt by the Conservative Government in April 2015 through the introduction of a raft of measures intended to ‘cut the red tape’ (a key conservative policy) of UK planning functions and allow for greater freedoms for both business and home owners. This document (The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015) amended previous General Permitted Development Orders to include the provision for office buildings to be converted to dwellings without the control of Local Planning Authorities.

Permitted development is defined within the Governments Planning Practice Guidance as being “…a national grant of planning permission which allow certain building works and changes of use to be carried out without having to make a planning application. Permitted development rights are subject to conditions and limitations to control impact and to protect local amenity.”

This study will therefore examine how the introduction of the ability for developers to alter offices to dwellings without any direct control by the Local Planning Authorities will actively affect the housing shortfall of England, being the purpose for its introduction.

In addition, to the above main aim, the project will also look at the interplay between the Governments policies of Localism and the drive towards a free open market for developers, and whether such deregulation of power is contrary to the Localism rhetoric.

It is suggested by Goodchild (2010) that whether in power or in opposition, the planning policies of the Conservative Party are caught in a tension between the free market and local communities. On one side, they face developers who want to simplify the planning system, speed up decision making and make sufficient land available for economic activities. Whilst on the other they face local authorities and the electorate who wish to see protection of local amenities, environment whilst promoting goof consultation and effective forms of managing development.

In order to meet the aims and objectives of this research proposal, it proposed to undertake an interview with numerous stakeholders from the town planning and construction industries, development companies, housing associations along with community and local residents groups within Newcastle upon Tyne and Middlesbrough. This will allow for the opportunity to gauge a full understanding of their perspectives both in a professional and personal context in relation to the objectives above, and generate sufficient data to influence the data analysis.

Having considered the possible available sampling strategies as set out by Patton (2002) it is considered that the most appropriate strategy in relation to this research will be to use a snowball or chain sampling strategy.

It is anticipated that by using this sampling methodology it will allow for the greatest opportunities to access people with the greatest information rich potential as viewed by their peers. It is acknowledged that initially the sampling field will extend exponentially, as each contact interviewed highlights new potential key people to contact and discuss the matter. However, as Patton states eventually the possible sources of information will “…then converge as a few key names get mentioned over and over.” (2002, p237).

3.0 Housing need and opportunity

The Government by removing the need to obtain planning approval for the conversion of office to residential accommodation have indicated the use of office buildings as a key opportunity in solving the housing shortfall issues being experienced by the UK.

However, there is no evidence that this de-regulation is based on any rigorous analysis of the available office space, and whether this type of accommodation will be suitable both practically through the physical constraints of the buildings, and whether suitable within the proposed locations, outside of the major UK cities, where city centre living is an attractive and viable option.

3.1 The Government estimates

The consultation paper ‘Relaxation of planning rules for change of use from commercial to residential’ issued by the Government in 2011 which initially proposed the change in planning control provided high level calculations and assumptions on what they considered to illustrate the possible benefits should this new permitted development right be introduced. They suggested that:

- On average across 2008/09 and 2009/10 there were around 15,135 dwellings which came from change of use. Of these we estimate around 3,900 were from B1 to C3. This represents just 0.2 per cent of the stock of B1 floor space per annum.

- On average across 2008-09 and 2009-10 there were around 15,135 dwellings which came from change of use. Of these we estimate around 8,300 were from B1, B2 and B8 to C3. This represents just 0.4 per cent of the stock of B1, B2 and B8 floor space per annum.

Further estimates within the consultation document suggest if there were to be an increase in the conversion rates of B1 uses to residential uses from the present 0.2% to 1% this would result in the an estimated 25,830 additional dwelling being created each year; and should the permitted development rights be extended to include B2 and B8 uses this would see an increase in new dwellings by 58,983 per year.

The consultation paper goes on to suggest that there is a vacancy rate of approximately 7%-9% within the B1, B2 and B8 use classes in England based on data between 1998 – 2005 (see table below).

| Estimate of maximum dwellings from current stock of floorspace | Vacancy rate* | Estimate of maximum dwellings from vacant floorspace | Estimate of maximum dwellings from long term vacant floorspace** | |

| North East | 319,733 | 7% | 22,381 | 11,191 |

| North West | 910,640 | 10% | 91,064 | 45,532 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 726,747 | 8% | 58,140 | 29,070 |

| West Midlands | 744,793 | 8% | 59,583 | 29,792 |

| East Midlands | 665,953 | 11% | 73,255 | 36,627 |

| East of England | 594,053 | 8% | 47,524 | 23,762 |

| London | 711,120 | 11% | 78,223 | 39,112 |

| South East | 735,813 | 9% | 66,223 | 33,112 |

| South West | 489,427 | 6% | 29,366 | 14,683 |

| England | 5,898,280 | 9% | 525,760 | 262,880 |

Source: Relaxation of planning rules for change of use from commercial to residential – Consultation (2011, p59)

The Government further make the assumption that if 50% of the long term vacant space is converted this would deliver around 262,880 new dwellings to the England housing market.

Whilst the above estimate and assumption appear to show that the proposed changes will be beneficially to the housing market within the UK. It is considered that the Government housing estimates and assumptions, may not fully appreciate the ‘real world’ barriers to the conversion of offices to residential units; such as the geographical variations between the regions particularly the South-east and North-east, in terms of the demand for such accommodation, the physical barriers to converting offices (discussed in section 5.0).

3.2 Historical context

The adaptation and conversion of buildings to facilitate re-uses of an existing building is not a new phenomenon, but rather it is suggested by Remoy and van der Voordt (2014) that conversion and adaptive re-use of buildings has taken place in all places at differing scales at all times throughout history, and has contributed to the historical diversity and interest of cities.

It is cited by Remoy and van der Voordt (2014) that Amsterdam’s canal-houses are a good example of where the adaptive re-use of buildings has occurred. These 17th century buildings have had their functions change numerous times throughout the existence; from warehouses to housing, to offices and back to housing.

As mentioned above, adaptive re-use is not a new phenomenon, but rather it has been in operation since the dawn of man; and draws of the ingenuity of humans to best use resources available to them.

The ingenuity and resourcefulness to re-use resources is evident more than ever in the modern era, where there exists a consciousness over use and management of resources.

3.3 Housing shortfall

It is often cited by commentators that the UK is suffering from a housing shortfall crisis that is leading to the greatest challenge for the Country to meet the aims of the population. Indeed it is a stated outcome of this Government that this policy will allow the creation of greater number of residential properties within the market. However, it is worth investigating whether there is indeed a housing shortfall (i.e not enough housing to meet the population growth), or whether it is a housing affordability issue that has led to this apparent crisis.

The housing need within England remains a key concern in relation to housing availability and affordability tin relation to the increase population growth is a significant factor in the creation of the housing need issue. There have been previous attempts by the Government to address the issues of housing numbers through the abolition of Regional set housing figures, to allow each individual Local Authority the ability to determine their own housing needs and requirements. However, it would appear that this has not assisted in reducing the shortfall.

3.4 Household growth and housing options

The latest Government household projections based on 2014 figures and projected to 2039, indicated that the number of households required within England is projected to increase from 22.7 million in 2014 to 28.0 million in 2039, an increase of 5.3 million households over that period, which would equate to the need for 212,000 additional household per annum to meet with the projected demand.

However, as previously mentioned there has been a housing shortfall in the total number of residential units being completed in contrasted to the required number to meet year on year demand. According the national housing completion figures released by the office of national statistics, between 1980 and 2017 (financial years) the average annual housing completions in England totalled 151,906. This is a shortfall of over 60,094 households per year, and if this trend were to continue until 2032 this would equate to a housing shortfall of approximately 1.3 million homes.

It is this year on year shortfall in the available housing to the market that has partially led to the affordability issues, and high residential housing prices within England, due to the supply and demand economic principle.

It is recongnised that the type of housing required will not be all of the same standard and that differing household will require differing type of housing to meeting their needs. The 2014 Houshold Projections state that “one person households are projected to increase by 68,000 per year, about one third (33 per cent) of the total household growth by 2039” (ONS, 2014)

It is acknowledged that the renting market is recognised as more usually being related to small houses and flat/apartment developments, which are likely more attractive to the one person household, this therefore would indicate that there will be likelihood for an increase in this type of development particularly in large urban settings.

3.5 Regional variation housing need

Looking at England as a whole, it is widely considered that there are significant differences and variations between the needs and requirement of the different regions of the country. In relation to the North East the housing projections show that in 2020 the Tees Valley Local Authorities (Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton on Tees) will required 295,000 new homes, whereas the Inner London Local authorities (Camden, City of London, Hackney, Hammersmith and Fulham, Haringey, Islington, Kensington and Chelsea, Lambeth, Lewisham, Newham, Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Wandsworth and Westminster) will require 1.62 million new homes. Whilst it is acknowledged that the populations of these places are vastly different the geographical areas they covers are similar.

3.5 Conclusion

The above analysis of the Government aims and objectives, and the available statistical information have shown that the there is a significant shortfall in the housing completion numbers against the requirements. The Government have indicated that a conversion rate of 1% of the vacant B1 uses nationally would deliver approximately 26,000 addition housing, which would equate to approximately 43% of the annual housing shortfall. However, it would appear that the Government have failed to look into the regional variations, and the household projections that predict approximately only 33% of the housing market need will be one person households, and therefore, the Government appear to be legislating for 10% more flatted developments per annum than the market needs.

Questions are therefore raised as to the need for the de-regularisation of the Permitted Development rights of the whole country rather than targeted at the area whereby the freeing up of B1 offices can have the most impact. Indeed it is somewhat further confused by the Government allow excemption from the legislative change for parts of central London whereby this change could bring about the most significant change.

4.0 Planning Policy Implications

Whilst the removal of the requirement for planning permission has been stated by the Government as a removal of the red-tape holding up development, and will deliver a significant amount of new housing in to the national housing stock. It is noted that the removal of planning controls whilst having some benefits as details above may have greater implications for the wider communities within which these conversions occur, that could have been mitigated had the control remained within the powers of the Local Planning Authority.

These issues were raised by planning professional and interested parties in the consultation response to the proposals which saw 64% of respondents not supporting the proposal.

The main areas of concerns related to the potential loss to the communities and the potential planning gains being lost through the permitted development rights. Concerns by respondents and commentators to the proposals highlighted that this proposal will lead to a significant reduction in the availability of employment spaces for current and future businesses. In addition, significant concern was raised in removing the ability for the Local Planning Authority and the Communities they served to democratically plan for the best use of their local areas, ensuring the appropriate needs of residential and commercial employment needs are being met, which has long been a keystone of the planning system.

In addition to the above, the removal of the need for planning permissions removed the ability of the Local Planning Authority to seek planning gains in the way of ensuring that the residential properties were subject to the meeting appropriate standards and/or planning obligations. The removal of the planning control could see areas losing out on potential vital contributions to affordable housing, and other s106 obligations that could provide essential local facilities and services, infrastructure projects, or carbon reduction initiatives.

As detailed above a keystone of planning and particularly Development Management / Control is to ensure that the developments deliver high quality developments that enhance both the visual and residential amenity of both the occupiers, as well and enhance or compliment the area. The loss of the control by the Local Planning Authority will inevitably lead to sub-standard developments in terms of the both the residential amenity of the occupiers through high density development, with low level of internal living and amenity standards.

It would appear that the Government in their response the consultation believed that the potential benefits to the available housing stock outweighed the professional opinions of those who responded to the consultation exercise. This therefore draws into question the meaningfulness of the consultation, and whether the exercise was simply tokenistic or non-participative as detailed in Arnsteins ladder of engagement (Arnstein, 1969).

The inability for planning professionals to effectively plan for these conversions will ultimately lead to the amenity of the occupiers, neighbours and the area will be left to the developers and market to dictate, whilst Local Authorities will still be required to deliver their statutory duties to the occupiers.

4.1 Conclusion

In conclusion to this section, it is shown that the introduction of the permitted development rights will have a significant impact on the ability of the Local Planning Authority to appropriately plan for their areas, whilst ensuring that the needs of the residents, local area and occupiers and users of neighbouring buildings are not adversely impacted by the uncontrolled adaption of offices to residential; but rather the provision and quality of the facilities being provided will be left to the market and the developer to dictate.

Additional, the Local Authority will have to manage the significant additional financial burden placed upon the authorities that are not mitigated through development contributions.

5.0 – The views of the planning professional

Having examined and analysed the consultation and legislative aims of the Government in the introduction of this policy, it was considered appropriate to find out the views of the planning professionals working within the Local Authority of Middlesbrough which has been the focus of this study. In total the whole of the Development Control team were issued questionnaires that sought their views on the permitted development rights and their opinions on the change. The following details the views obtained:

- When asked whether there were pressures on the Local Authority area to provide residential accommodation, 100% of the respondents stated that there was a pressure.

- When asked where they felt the pressure came from approximately 66% of the respondents stated that the pressure was both demand and supply led.

- All respondents stated that the Local Authority had specific policies which encouraged city/ town living; however, all respondents also stated that the Local Authority did not encourage living in the town centres through the conversion of offices.

- The majority of respondents stated that there were housing density standards which would adversely affect the conversion of office buildings.

- In regards to car parking standards the respondents indicated that there were specific standards required for flatted developments (2 spaces per flat), however, that in town centre accommodation this would be significantly reduced.

- The majority of the respondents did not consider there to be any significant barriers to the conversion of offices to residential indeed one respondent commented “fairly easy process for the conversion of this type, especially under permitted development”. Issues were highlighted in relation to noise attenuation issues and highway issues.

- In relation to the introduction of the permitted development rights, the respondents were asked whether they considered it to be beneficial to the Local Authority in meeting the housing demand or in place making?. The general consensus of the respondents was that there had been no noticeable impact on the housing provision, and that in terms of place making the removal of control has led to issues in relation to deliver of high quality development, and housing.

- Since the introduction of the permitted development right, it was revealed that the Local Authority had received prior notification for four conversions, and that of those conversions the following issues had been experienced – Noise and Highways implications, high density of units and the quality of the provision.

- When queried regarding the drivers for the conversion, the respondents believed that the main drivers were that developers were able to maximise their profits through high density developments, where no control was present or requirement to pay a planning fee.

- When questioned as to whether they considered the conversion of office would be a suitable and attractive place to live. The majority of respondents stated that they did not believe it was a suitable place to live. One respondent believed that the suitability or attractiveness of this type of development was wholly dependent on the individual situation and location.

5.1 – Conclusions from the Planning Professional

In conclusion to the views obtained it is clear that the planning professionals surveyed were that the removal of the ability of the Local Planning Authority to control and manage developments of this type, have led to poor quality developments, that have had specific noise and highway issues. Additionally, the since the introduction of the permitted development right the authority has only experienced a total of four conversions of offices to residential, which appears to show that there is no demand for this type of development, and that it will not have the desired impact on the addition housing stock anticipated by the Government.

In addition, the Planning professionals have stated that the Local Authority has specific policies to encourage town centre living, but that they considered that offices did not lend themselves to appropriate developments.

6.0 Middlesbrough – Case Study

Following on from the view expressed above by the Planning professional working with the Middlesbrough Development Control team, it is considered expedient to turn to the town of Middlesbrough itself, to understand the town itself, its current housing provision, new dwelling building rates, to obtain an impression as to whether the proposed conversions will aid the housing stock and meet the needs of Middlesbrough and similar towns.

6.1 A tale of two towns

Middlesbrough, a town situated in the North-east of England, situated within the heart of was has become known as Tees Valley. The town, and Local Authority boundary are somewhat unique in that its perceived size, and geographical spread is often mistaken, and widely mistaken for a city within the media. The reality however could not be more different; the town and the Borough are a small in comparison to its neighbouring Local Authorities of the Tees Valley.

There is often a common misconception regarding Middlesbrough, by both the media, and those not familiar with the town. Middlesbrough is often referred to as being a city, and often considered as having a greater extent to its borders than it actually has, incorporating many urban settlements on its periphery, that actually fall within other Local Government Authority areas. However, paradoxically to this impression, Middlesbrough as a town and Local Authority whilst being densely populated is a town, and has the smallest geographically area then any of the adjoining Local Authorities.

It is in this context that Middlesbrough has been chosen as a case study for the impact of the de-regularisation of planning controls over office to residential conversion, on small urban locations where low land values and deprivation exist.

6.3 Middlesbrough – the beginnings

According to Moorsom (1967), Middlesbrough is a town that is almost unique within English history in its rapid development, and that “Middlesbrough is to England as the Gold-rush towns are to the United States of America” (Moorsom, 1967, foreword). The town developed from what had been a small rural farming community with a population of 40 people in 1829, 7,600 in 1851 to a major industrial metropolis of 20,000 by 1860. This incredible rapid growth, along with the abundance of natural resources, and the industrial infrastructures of the railways, led the town to become one of the most important industrial centres within the country. A town that was in 1862 was referred to by the eminent Victorian Politician and future Prime Minister William Gladstone as “This remarkable place, the youngest child of England’s enterprise, is an infant, but if an infant, an infant Hercules”.

Middlesbrough is colloquially known as “the town that built the world” owing to its industries being responsible for some of the most iconic buildings both nationally (Tyne Bridge, Newcastle; Forth Bridge, Edinburgh; and Canary Wharf, London) and internationally (Sydney Harbour Bridge, Australia; Victoria Falls Bridge, Zambia)

6.4 Post Industrial decline and out-migration

Whilst Middlesbrough’s rapid growth was built on industrial processes and associated industries. Its decline was almost as rapid as its initial growth owing to the issues experienced by Manchester as detailed in section 5.1.

Following the decline of its traditional economic base, there has been a population decline. The town’s population has “…decreased by almost 30,000 since 1961 and official predictions are that this trend will continue” (Middlesbrough Housing Strategy, 2008, p5). Therefore significant concerns were raised within Middlesbrough Council regarding the viability of the town in the long term, and the ability of the Local Authority to meets its statutory functions to residents especially in lights of the aging population (Middlesbrough Housing Strategy, 2008).

If this trend were to continue it is projected that by 2021 the population of Middlesbrough will have fallen to 130,000 (Middlesbrough Housing Strategy, 2008), which is primarily due to out-ward migration of residents to neighbouring Local Authority areas, as the housing stock and areas are failing to meet the aspirations of the residents.

This outward migration of the population due to the failure to provide suitable housing stock was something that the Local Authority sought to resolve through Planning Policy, to reverse this trend. However, the following the introduction of this permitted development right, the ability for the Local Authority to appropriately plans for the needs of its residents appears to have been taken from their control.

6.5 Housing Needs

The Tees Valley Strategic Housing assessment provided details of the predicted dwelling types required to meet the aspirations of the existing households. As can be seen over 74% of households were expecting to move to a house or bungalow, as opposed to 26% of households seeking flatted accommodation.

| Type preferences | Existing (%) | Newly-forming (%) | Total (%) |

| Detached | 10.6 | 8.3 | 9.3 |

| Semi-detached | 28.7 | 31.8 | 30.5 |

| Terraced | 18.9 | 28.4 | 24.5 |

| Flat | 21.5 | 28.8 | 25.8 |

| Bungalow | 20.2 | 2.7 | 10.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Base (annual requirement) | 1166 | 1632 | 2344 |

Source: Tees Valley 2012 Strategic Housing Assessment Final Report. p193

Therefore, it is clear that the priority for Middlesbrough in order to meet the needs of the residents is to provide non-flat/apartment developments.

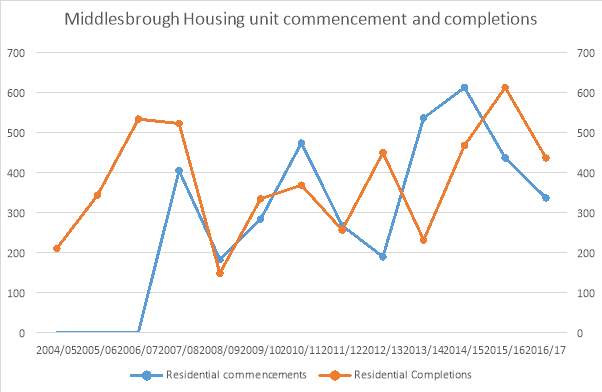

The following figures obtained from Middlesbrough Council detail since 2004/05 the number of housing units commenced and completed per year. These figures indicate that despite the economic crisis experienced by the UK the housing figures remained steady

| Year | No. of housing units commenced | No. of Housing units completed |

| 2004/05 | No Data | 210 |

| 2005/06 | No Data | 343 |

| 2006/07 | No Data | 533 |

| 2007/08 | 404 | 522 |

| 2008/09 | 182 | 148 |

| 2009/10 | 283 | 334 |

| 2010/11 | 473 | 368 |

| 2011/12 | 267 | 256 |

| 2012/13 | 189 | 449 |

| 2013/14 | 536 | 231 |

| 2014/15 | 612 | 467 |

| 2015/16 | 436 | 612 |

| 2016/17 | 336 | 436 |

| Totals | 3718 | 4909 |

Source: Data obtained from Middlesbrough Council (July, 2017)

These figures provide an insight into the Middlesbrough Housing Market that shows it to be a relatively steady market that is not particularly impacted by externalities in the wider economic climate.

The Department of Communities and Local Governments projections for Middlesbrough in 2008 indicated that there was an annual need of 310 dwellings required to meet the needs of Middlesbrough, this projection increased to 320 in 2011, which was largely supported by the 2012 Tees Valley Strategic Housing Market Assessment that stated a requirement of 333 additional dwellings would be required per annum between 2011-2026.

| Household change

2011-2026 |

Tenure | ||

| Market | Affordable / Intermediate | Total | |

| Total | 3631 | 1369 | 5000 |

| Annual | 242 | 91 | 333 |

| % | 72.6 | 27.4 | 100 |

Source: Tees Valley Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2012

Analysis of these figures shows that Middlesbrough is not experiencing a housing crisis that is being experienced in other parts of England, but rather the supply of housing is delivering above the projected minimum requirements.

6.5 Strategic Housing assessment

Therefore, as the need for un-regulated additional housing provision as stated as being one of the key drivers behind the introduction of this permitted development right has been shown to not be required within Middlesbrough, It seems prudent to examine whether there is an actual need for apartments or flats within Middlesbrough.

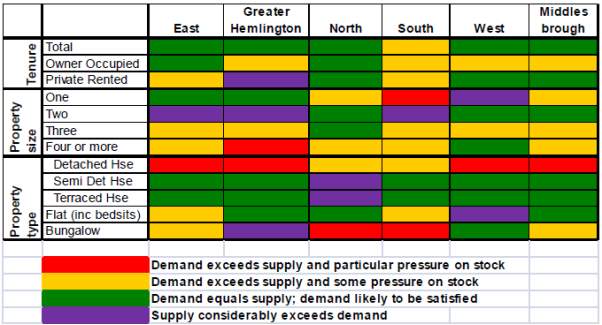

The Tees Valley Local Authorities undertook a strategic housing assessment in 2012 that looked specifically at the housing stock currently within the Local Authority areas within the Tees Valley, as part of this study it examined the housing stock availability against the demand. The following table indicated via a traffic light system the where there was significant demand and over-supply of housing types.

Source: Tees Valley Strategic Housing Assessment, 2012, p67.

It can be seen from this study that the supply of apartments / flats equals the demand for this housing type, and that in the Western sections of the town that includes the town centre, considerable exceed demand. Therefore the need for apartments is shown to not being required.

This view was supported in 2008 prior to the introduction of the permitted development rights within the Middlesbrough Housing Strategy that there was already significant concern regarding the recent increase in the number of apartments being constructed. It highlighted that “The LDF (Local Development Framework) already includes policies which seek to limit such supply in certain parts of Middlesbrough and this area” (Middlesbrough Housing Strategy, 2008, p53)

Therefore, it can be assumed that the ‘need’ for apartment type of housing is not necessary within Middlesbrough. So, the question then is why are the Central Government who have championed Localism and bringing planning decision back to a local level chosen to deregulate the housing supply market with a top down market led approach to housing supply, whereby Local Authorities and people have no control, or input into where, and how many of these apartments will be brought forward despite the needs of the place.

5.0 Manchester – an example of a different approach – Case Study

The following case study is taken from the work of Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013), who undertook a full study of Manchester, and its reuse of industrial built heritage for residential purposes.

This case study has been chosen as it shows that there is a different way in which conversion of derelict commercial buildings can be converted to residential and other active uses, through strategic joined up thinking and policy making, rather than opening it up to the market to lead and dictate with ad-hoc developments.

5.1 The bust – Manchester post 1970s

Manchester was at one time labelled by the Thatcher Government as being a symbol of ‘British disease’ (O’Connor and Wynne, 1996 cited in Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013)), because of its social, economic and environmental problems which became more visible in the late 1970s following the economic downturn and de-industrialisation.

5.2 – The Post-Industrial boom

It is suggested by Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013) that in the wake of the macro-economic impact on the city during the 1970s, policymakers undertook a process of urban re-landscaping and re-imagination, within which the industrial heritage, cultural and social conscience of the city took an important role. This has led to the investment, in improving post-industrial buildings to encourage new functions within these areas, and created new types of economic activities through providing alternative uses to the redundant industrial buildings and sites rather than demolition and redevelopment as would have been the case in the decades preceding.

This policy led to a number of key successful initiatives undertaken through partnerships between the Council and Private Investment, including Castlefield, the country’s first Urban Heritage Park that was designated in 1982, the conversion of the Liverpool Road Passenger Station terminus into the Museum of Science and Industry in 1984, and the Lower Campfield Market that was converted to house the Air and Space Gallery, and finally in 1986, the Central station was converted into an exhibition centre known as G-MEX.

Following on from the early successes of these partnerships, Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013) suggest that the Central Manchester Development Corporation (CMDC) was formed in 1988, to carry on with the work of these partnerships and saw partnerships between the City Council, government agencies and private developers to develop way in which growth in the city could be maintained through the introduction of new functions and activities to the old industrial buildings and areas. Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013) use examples of the former cotton warehouses that were converted into apartments, former factories into office complexes with the grants from CMDC, English Heritage and the EU Regional Development Fund. Middle Warehouse, now called Castle Quay, another former canal warehouse in the same area was converted into luxury flats, offices, retail units and a café. Not only warehouses and factories were converted into the spaces of the new lifestyle but also railway viaducts were restored and reused as cafes and bars, all to supply the ancillary, and complementary uses required by the occupants of the buildings.

The CMDC was disbanded in 1996 but in eight years it built 2583 housing units, provided 97,904 m2 of office space and created thirty-eight leisure schemes (Parkinson-Bailey, 2000 cited in Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013)).

5.3 Conclusion to the Manchester approach

The work by Mengüşoğlu and Boyacioğlu (2013) clearly shows that there is another approach to the revitalising of vacant buildings to provide additional housing through strategic policy, partnership and regeneration initiatives; as opposed to de-regulating the market. In this example in eight years the Central Manchester Development Corporation was able to deliver 2583 houses equating to 323 per annum.

7.0 Barriers to conversion

There has been significant research and studies into the barriers and drivers to the conversion of offices to residential. Therefore, it is not considered expedient or necessary to further research this aspect through discussions with professionals involved in this field. However, rather for the basis of this work it is intended to examine the empirical data from these studies and expand on their findings.

The deregulated provision allowing for the change of use of offices to residential accommodation and the conversion works would, in theory, appear to be a relatively simple task involving the physical alteration of the building prior to letting to potential occupiers. However, there are significant other barriers to the success of conversion works that have been identified by Heath (2001) and Barlow and Gann (1996).

Heath (2001) suggests that there are five primary areas of concerns when adapting offices to residential accommodation; these being:

- Physical or Design

- Locational

- Financial or economic

- Demand

- Legislative

Heath, also is clear that there are a number secondary barriers beneath each of the primary barriers that are need to be addressed in order to deliver a successful scheme. The table below outlines this work by Heath.

PHYSICAL OR DESIGN

|

DEMAND

|

LOCATIONAL

|

LEGISLATIVE

|

FINANCIAL/ECONOMIC

|

Source: Heath (2001) p182

The study from Heath (2001) indicates that the success to conversion of office buildings to residential accommodation is significantly more complicated than the physical alterations to the building as would be indicated by the change in Government legislation, and that there are specific and external factors needed to deliver a successful outcome.

This view is supported by the work of Barlow and Gann (1996) who undertook a study into the technical feasibility of converting offices to residential accommodation. Their research concluded that whilst the technical constraints to conversion of offices were rarely insurmountable on their own there were seven significant technical points that would need to be addressed in order for a scheme to be feasible. “We found the following.

- It is technically easier to convert older brick-built offices or offices in former houses than purpose built office buildings.

- The ease with which purpose-bulit offices can be converted depends on the size and height of the building, its depth, envelope and cldding, internal structure, services, acoustic separation and fire safety.

- There is no optimum building size, but large modern office blocks may result in unacceptably high density if converted.

- Technical feasibility also depends on the proposed use, for example, conversion into a hostel might be easier than conversion into permanent flats.

- Office buildings designed before the 1980s are inherently easier to convert than modern buildings: steel-framed buildings are easier to convert than concrete structures because of implication for the installation of services. Building with large panel or in situ masonary cladding systems are more suitable for conversion.

- The main fire brigade, fire detection and alarm, prevention of flames spreading.

- A number of different technicques can be used for conversion, including the use of prefabricated modular units which may speed conversion and reduce costs under certain circumstances.” (Barlow and Gann, 1996, p64)

The work of Heath, Barlow and Gann detailed above shows that the success of conversion of offices to residential dwellings is not as simple as it may initially appear, through removing the an element of the legislative barriers, and that there are more significant and crucial barriers to the conversion, in delivering a successful scheme that maybe insurmountable.

3.3

Type and condition of buildings

Although in most urban areas there are examples of vacant commercial space that theoretically create opportunities for residential conversion, there simply is not the evidence to accurately quantify how many have genuine practical potential.

Office space

It is generally considered that the space most suitable for conversion to residential will be office space (B1), rather than general industrial use and warehousing (B2, B8). This is because office buildings have been designed for occupation, placing greater importance on issues such as daylight and ventilation than many typical industrial or warehouse buildings. Because the requirements of office buildings have a greater similarity to those of residential, and are generally in more accessible locations, we agree with the CLG that change of use from B1 to C3 would be the ‘key proposal’.

However, the age of any existing building is likely to be a key determinant. In broad terms, office buildings can be grouped into three categories:

A: pre-1945 buildings;

B: 1945-1970s; and

C: 1980s to present day.

Generally speaking, the shift in format and design between these vintages has an impact on the practical viability of conversion potential.

A: Pre-1945 buildings

Pre-1940s construction, buildings types such as Victorian warehouses, are likely to differ to the typical post war office building in the way they can be converted. Often, the building will have load bearing masonry walls instead of a framed structure, which is more typical post war. For these buildings, compliance with current regulations for improved thermal performance of the building envelope would most likely result in applying new insulation internally and replacement windows. Because the potential to insulate internally is unlikely to require significant alteration to the building’s external appearance (beyond window replacement, landscaping etc) such schemes are less likely to trigger the requirement for a planning submission. Conversion schemes that can be internally insulated may therefore have reduced standards placed upon them by planning authorities. It is nonetheless still possible that a planning application for external amendments will be required if, for example, the building has historic value. However, in this scenario, the character of the existing building often makes these types of conversion projects more desirable to buyers. Although in theory there is a reduced risk in taking forward pre-war buildings, there are still some challenges:

• Supply – a smaller supply of such building types compared to post-1950s B1 stock will limit the scope of these types of buildings contributing any significant development opportunities.

• Internal disruption – internally insulating to sufficient standards can take up significant floor space (as indicated by Figure 4 on the previous page).

• Flexibility – designing a residential layout within existing window openings of a commercial building can be limiting to the proposed layout. This may cause fewer individual dwellings to be created from the equivalent floor space of a re-clad project where openings may be more flexible.

• Energy consumption – high level energy efficiency is more difficult to achieve when renovating internally. Issues such as cold bridging and air tightness are likely to more problematic than in a re-clad approach.

• Heritage Issues – many pre-war buildings may have heritage constraints that limit conversion potential. Listed buildings come with additional sensitivities that can constrain the opportunities for conversion, while being located in a Conservation Area could create added complication and expense.

B: 1945-1970s buildings

The design of post war office buildings has developed to accommodate changes in relation to servicing and information technology. The format of offices built over the past 60 years fall into two distinct typologies – 1945-1970s, and 1980s onwards. Of these, the former perhaps present more opportunity for conversion, being more likely to have reached the end of use cycle or be in a location where the market has moved on.

In practical terms, the key characteristics of commercial buildings built between 1945 and 1970 are:

• Framed structure – generally concrete, as opposed to masonry load bearing walls.

• Shallow plan width (approx. 10-14m). These are more suitable to accommodate apartment layouts as depth of plan and orientation of existing floor plates are more adaptable allowing adequate daylight for residential layouts.

• Slab to slab floor heights of approximately 3m, and constraints on floor loadings means that servicing requirements for modern office occupiers are not easily accommodated, meaning that these buildings are more likely to remain vacant.

• Looking to the future, increasingly stringent energy efficiency requirements will add further pressure on costs of upgrading older office stock. A recent report from the British Council of Offices suggested that as F and G rated properties are banned from 2018 onwards, more than 60% of private sector office buildings in London could become obsolete.

Although post-war / pre-1970s commercial buildings are most likely to be viable in terms of conversion to residential, and are in some cases perhaps most likely to be vacant, most of these buildings in a conversion project are likely to require significant upgrades to the facade, which will usually require planning permission for the operational development.

C: 1980s to present buildings

Office buildings post-1980 tended to be created on a deep plan format (between 15-18m) which are not easily adapted to suit residential layouts, principally due to the ratio of floor space versus façade which restricts the positioning of windows to habitable rooms. All things being equal, the higher floor to floor heights (between 3.7-4.2m) are still more likely to accommodate modern office servicing requirements, therefore reducing the likelihood of these types of office buildings becoming vacant in situations where the market for office space remains reasonable.

Industrial buildings

Although there are likely to be a number of buildings with potential, the government’s view is that general industrial or warehousing (B2 and B8) type buildings are often in the ‘wrong’ location or physically unsuited for adaptation and would generally require rebuilding, thereby triggering a full application. Often located in single-use industrial estates, unless the scale of conversion is comprehensive, or the plot is on the periphery, market forces are likely to limit potential. However, even in a favourable location, the construction of many industrial buildings are often unsuitable for conversion due to factors such as access to daylight, and longevity of materials (portal frame buildings such as the image below).

8.0 Conclusions

Reflecting back on the aims of this project as set out in section 1.3. This project sought examine three specific aims relating to the deregulation of the ability of the Local Planning Authority to control and regulate the conversion of offices to residential use. It is therefore proposed to examine each aim in turn and draw a conclusion from the research undertaken:

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Construction Law"

Construction law concerns the legal practice of dealing with matters related to construction projects, infrastructure, engineering, and related fields. Construction law includes elements of contract law, commercial law, planning law, employment law and tort.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: