Impact of Geographic Access on Intuitional Delivery Care Utilization in Low and Middle-income Countries

Info: 11201 words (45 pages) Dissertation

Published: 9th Dec 2019

The impact of geographic access on intuitional delivery care utilization in low and middle-income countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Background

Access to and quality of health services are a high priority for investments designed to increase health services utilization which eventually improve health outcomes (1). Healthcare access is defined in terms of geographic, financial, temporal, digital/eHealth and cultural access, and availability of services (2, 3). The digital dimension of healthcare access addresses the digital connectivity/communication with healthcare providers, peer groups, and computerized health applications (2). Temporal access addresses the time required to get services (waiting time in reception, time spent in receiving treatment and time to next appointment) and its trade-offs (2). Availability is the opportunity to get the right type of healthcare, appropriate healthcare providers, materials and equipment (3). Financial accessibility focuses on the costs of services, and users’ ability and willingness to pay for, as well as to be protected from financial consequences of health care costs (2, 3). The cultural dimension of access focuses on the acceptability of health services to individual users and communities, such as language match, trust to provider and public stigma. On the other hand, the geographic dimensions of access is the measure of the physical distance or travel time to service delivery points (2, 3).

People living in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) tend to have less access to health care services than those in high income countries (3). Furthermore, within these countries, the poor and those living in rural areas have less access to these services (2, 3). In rural areas, and for congested urban centres, the geographical dimension of access could be more important than urban centres with good transportation infrastructure; in those settings, service users might be expected to walk long distances and/or spend more time on travelling (2). Availability of transport services, nature of roads (seasonal impassibility), mountains and rivers may also play a role in accessing health care services (4).

Moreover, for any reason, the nearest health facility might not be the facility of choice. Not all services are provided at all levels of health facilities (4). For instance, in many countries, comprehensive emergency obstetric care (CEmOC) is not available at the lowest health facilities. In most countries, it is only available at hospitals, and for this reason pregnant women and their families may be required to travel further away for childbirth (5).

Studies from Zambia and Malawi found that the odds of facility delivery was higher among those who had physical access to higher level of care facilities (6, 7). Analysis of the 2012 Haiti DHS and 2013 SPA data found that health facilities service readiness within 10 kilometre of radius of a given cluster was associated with an increased use of delivery services (8). Similarly, in Malawi and Zambia, living close to facility providing delivery service was significantly associated with health facility delivery (7). It was also noted that the increase in geographic distance was associated with a decrease in the use of health facility delivery (6, 9).

However, it was found that having access to obstetric care facilities within one-hour (10, 11) and three kilometres (12, 13) of distance were not significantly associated with institutional delivery. Therefore, this study synthesized the evidence on the influence of geographic access on institutional delivery care use in low and middle-income countries.

Method

Search strategy

Our search included the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus and Maternity & Infant Care. We used multiple combinations of search terms or keywords, such as delivery care, geographic access, observational studies, low and middle-income countries, and Boolean operators (Table 1). The searching terms/keywords first used in OVID MEDLINE were adapted to the other databases. We also conducted a hand search of reference lists.

Study selection

Search results were imported into EndNote software to aggregate relevant articles and to manage duplications. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts to determine if the returned electronic search articles were related to the study. The respective lists of articles of both authors were combined and full-text articles were reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer, and we calculated inter-reviewer reliability; that is, the percentage of agreement between reviewers (Cohen’s kappa) (14).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies only conducted in low-income and middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank (15) and published in English. We took studies published since 2000 that was the introduction of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) up to December 31, 2016. We have included quantitative cross-sectional studies, cohort and case-control studies. We excluded experimental or intervention studies and organization reports in our analysis. The studies had to report on the influence of geographic accessibility on maternal delivery service use.

Outcome measures

We selected articles that reported geographic access on delivery care use. Our outcome measure was utilization of institutional delivery.

Study quality assessment

Two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of each study using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data (16) and cohort studies (17). Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

We extracted data on influence of geographic accessibility on maternal delivery care use. We used data extraction form that include general information (publication details and country), and specific information (study setting, study design, study population, sample size, main findings) (Table 2). We created a summary matrix with the data extracted from all individual studies. Two authors independently extracted the data from the included studies into the constructed matrices. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and the original study was reviewed to resolve further discrepancies.

Analysis

The results of studies were extracted, reviewed and reported in a systematic format. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA ) checklist (18) was used to synthesize and report the findings. A meta-analytic procedure was used to compute and aggregate effect sizes. The pooled effect size (Odds Ratio – OR) was calculated using a random effects model. The Q statistics, I2 and Tau squared (τ2) were used to examine heterogeneity of studies. The analysis was done using ProMeta software, version 3.0.

Results

Search Results

We retrieved 394 articles, of which 33 duplicates were removed. Three hundred ten articles were excluded based on title and abstract. The remaining 51 articles were reviewed using a full-text article. Twenty articles were excluded; for instance, four were focused only on skilled birth attendant (19-22), and were not for the general population (23, 24) (Fig 1). Thirty-one studies were identified based on the eligibility criteria; 16 included in qualitative synthesis (systematic review) and 15 in quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) (Fig 1). Data extracted from the 31 studies are shown in Table 2. Four of the 31 studies were a linked analysis of population and health facility surveys (6, 7, 25, 26) (Table 2). With the exception of three studies (10-12), all the other studies showed a significant association between physical access and delivery care use.

Study quality

We evaluated the quality of the included studies using the JBI’s critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional and cohort studies (16, 17) and it turned out with an average score of 75.16%. Of the included studies, only three of them were graded as poor quality (27-29).

Heterogeneity test

Studies included in estimating the pooled effect of access to obstetric care facility beyond 60 minutes of travel showed that they were statistically heterogeneous. The Q-value was 23.23 with 8 degrees of freedom and P-value = 0.003. The I2 statistic (a measure of the proportion of the variance in the observed effects that is due to the variance in the true effects), was 65.56, which demonstrates that about 66% of the variance in the observed effects was due to the variance in the true effects. Tau squared (τ2) is the variance of the true effect sizes, whereas Tau (τ) is the standard deviation of the true effects (both in log units). The estimated τ2 and τwere 0.24 and 0.49, respectively. The prediction interval was from 0.06 to 0.77. Therefore, in most populations, we would expect that the odds ratio for delivery care use would fall from 0.06 (94% for those who had no access) to 0.77 (23% who relatively had access to obstetric care facilities).

In case of access to obstetric health facility within five kilometre of their usual place of residence, the included studies were not statistically heterogeneous. The estimated Q-value was 10.71 with 6 degrees of freedom and P-value = 0.098. The estimated I2 was 43.99, which tells us that about 44% of the variance in the observed effects was due to the variance in the true effects. The estimated τ2 and τwere 0.03 and 0.19, respectively. The prediction interval was from 1.34 to 3.85. Therefore, in most population, we would expect that the odds ratio for delivery care use would fall from 1.34 (34% for those who had no access) to 3.85 (285% who relatively had access to obstetric care facilities).

Additional records identified through other sources

(n = 39)

Records identified through database searching

(n = 355)

Identification

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 361)

Screening

Records excluded

(n = 310)

Records screened

(n = 51)

20 full-text articles were excluded:

Not in English (1),

Descriptive studies (4),

Didn’t report geographic access (6),

Not for general population (2)

Outcome variable not well-defined (3)

Only for skilled birth attendant (4)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n = 31)

Eligibility

Studies included in qualitative synthesis

(n = 16)

Included

Studies included in quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis)

(n = 15)

Fig 1: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis flow diagram adapted from the 2009 PRISMA Statement (18)

Impact of geographic access on delivery care use

Having no access to obstetric care facility within 60 minutes of walk

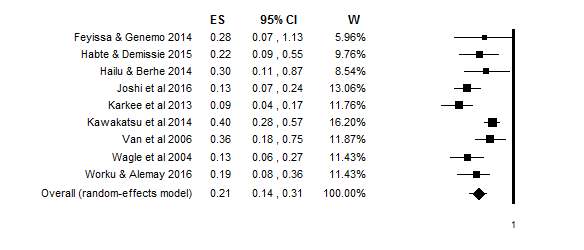

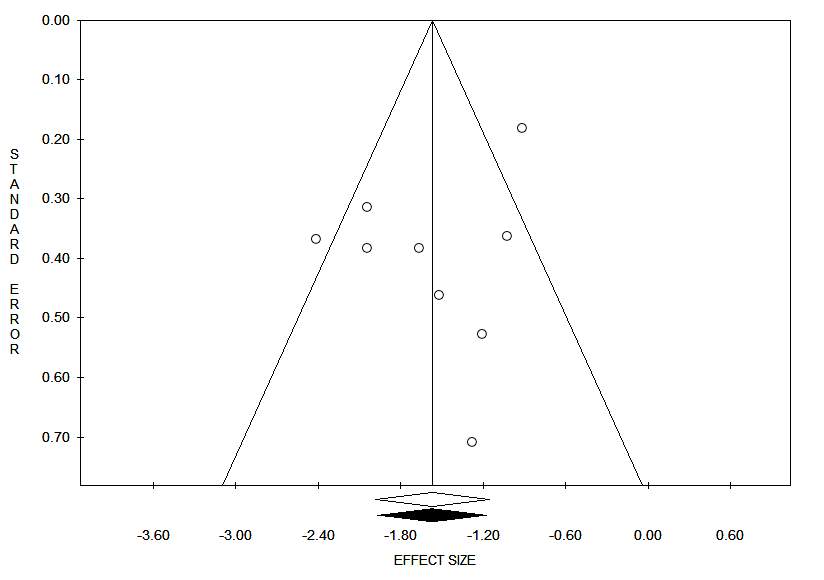

The pooled estimates (Odds Ratio) showed that impact of geographic access on institutional delivery care use was 0.21 (95% Confidence interval = 0.14, 0.31). This indicates that pregnant women who had no access to obstetric care facilities within 60 minutes of walk were 79% less likely to give birth at health institutions (Fig 2). The Trim and Fill analysis found that there is no need of additional studies to balance the symmetry of the funnel plot. However, the Funnel plot showed a slightly asymmetrical effect (Fig 3) but the Egger’s test found that there is no publication bias (P-value = 0.21).

Fig 2: Forest plot of effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals showing the effect of one hour and more travel time on delivery care use

Fig 3: Funnel plot on having no access to obstetric care facility within one hour travel time

Having access to obstetric care facility within 5 kilometre

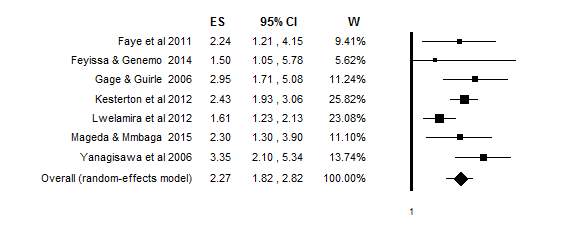

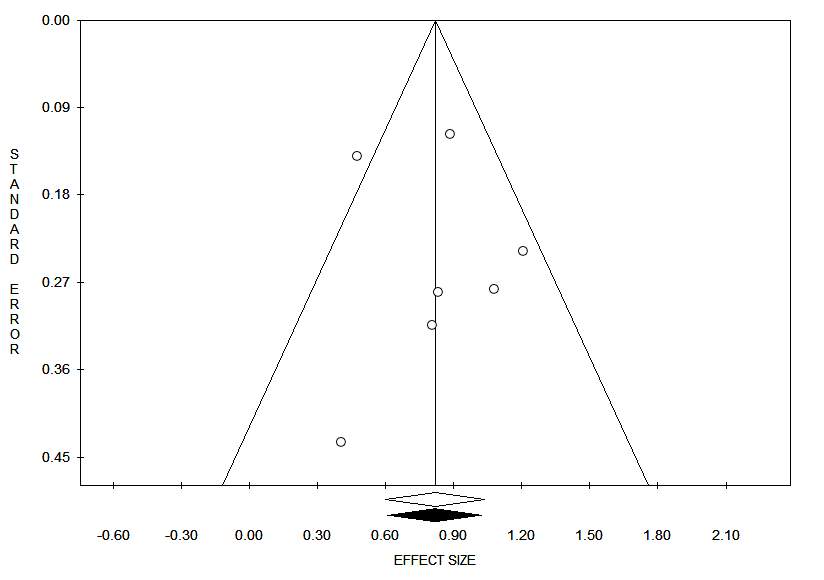

The pooled estimate found that pregnant women who had access to obstetric care facilities within 5km were 2.27 times more likely to give birth at health institutions (95% Confidence interval = 2.27; 1.82, 2.82) (Fig 4). The Trim and Fill analysis found out that no more studies are required to balance the symmetry. Both the Funnel plot (Fig 5) and the Egger’s test showed that there is no publication bias in the included studies (P-value = 0.74).

Fig 4: Forest plot of effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals showing the effect of geographic access within 5km on delivery care use

Fig 5: Funnel plot on geographic access to obstetric care facility within 5km

Furthermore, the qualitative synthesis of most of the studies showed that geographic access had an effect on obstetric care use. Physical access to obstetric care facilities was assessed in two ways; that is, in terms of geographic distance and travel time to health care facilities. Looking at travel time to reach nearby obstetric care facilities, when the travelling time goes down to half an hour and less, pregnant women were more likely to have health facility delivery (30). However, in another two studies, having access to delivery care facility within one-hour (10) and half an hour (11) were not associated with institutional delivery. One the other hand, every one-hour increase in travel time to the nearby obstetric care facilities was associated with a 20% decrease in the odds of facility delivery (26).

In addition to travel time, a one-kilometre increase in walking distance to obstetric care facilities was significantly associated with a significant decrease in health facility delivery (9, 25, 31-33). In rural Zambia, every doubling of distance to the nearest obstetric care facility was significantly associated with a 29% decrease in health facility delivery (6). Moreover, the odds of health facility delivery was decreased by 65% in Malawi and 27% in Zambia for every 10 kilometre increase in distance to the closest obstetric care facility (7).

The odds of health facility delivery was higher among pregnant women who had physical access to obstetric care facilities within 10 (25, 34) and five (28) kilometres. However, having access to obstetric care facilities within three (12) and two kilometres (13) were not significantly associated with institutional delivery care use. In Burkina Faso, pregnant women who were residing seven or more kilometres away from obstetric care facilities were more likely to have home births (35).

Discussion

The main findings of this meta-analysis and systematic review were that geographic access to obstetric care facilities, measured in either physical distance and/or travel time, had an impact on intuitional delivery use. Pregnant women who were living within a five-kilometre of an obstetric care facility had the higher odds of intuitional delivery as compared to those living beyond a physical distance of five-kilometre. In terms of walking time, the odds of using institutional delivery was low among pregnant women who had no access to obstetric care facilities within one-hour walking time. This implies that long distance has a dual influence on institutional delivery service utilization. It can be a barrier for both reaching obstetric care facilities and discouraging to seek care. The problem further worsens for rural pregnant women who often have no access to reliable transportation systems.

Furthermore, it was observed that both a single kilometre and a one-hour increase in accessing obstetric care facilities were associated with lower odds of intuitional delivery. This was consistent with the concept of distance decay (36), where interactions varied inversely with distance. The greater the distance, the greater the barrier and the less the interaction would be. Therefore, the further away a pregnant woman lives from an obstetric care facility, the less likely she will use institutional delivery service.

Even though the study was the first of its kind, it had several limitations. It took only one of the three delays model – delay in reaching health care facilities (37) and measures of healthcare access (2, 3); even it did not address the different means of transportation, travel costs and terrains. There were also variations in the operationalization and measurement of geographic access to obstetric care facilities. It was due to the unavailability of a universally agreed clear cut-off point, in either a geographic distance and/or travel time, for a health facility to be accessible or not. The World Health Organization has put distance and travel time as a measure of physical accessibility (38); however, there was no clear cut-off point for its measurement. Different countries are using different cut-off points; for instance, Ethiopia uses a 10 km (39) distance whereas the United States of America and the United Kingdom use 30 minutes of travel time (40) for measuring geographic access to health care services.

Even though the analysis was done using both distance and travel time, still it was subjected to measurement errors. The physical distance used in the studies was not uniformly measured; whilst some studies used a direct physical distance, the rest used walking tracks. Making comparisons and judgement based on measured physical distance is subjected to errors where the geography and transportation infrastructure largely vary within and among countries. Moreover, though the World Health Organization recommends using travel time, instead of physical distance, for assessing geographic accessibility (38) unless stratifications are used, it could pose problems in making a comparison. The value of and actual travelling time varies depending on people; for instance, age and condition of the person, and the transportation mode used, and thus its strength as access barrier varies too.

In conclusion, it was found that the more closely the obstetric care facilities, the more likely that pregnant women to use institutional deliveries. Researchers should account the different measures of geographic accessibility, taking into consideration of means of transportation, travel cost and terrains, for measuring how obstetric care accessibility and utilization of intuitional deliveries interact with each other. Furthermore, future research is also needed to compare each of the measures of health care access how they could influence utilization of obstetric care services.

Table 1: Search strategy for impact of geographic access on delivery care use

| Databases | Search Terms |

| Medline | Midwifery/ or Maternal Health Services/ or Perinatal Care/ or Delivery, Obstetric/ or Obstetric Labor Complications/ or Labor, Obstetric/ or Caesarean Section/ or Obstetrics/ or Parturition/ or childbirth.mp. or Obstetric care.mp. or delivery care.mp. or delivery assistant*.mp. or birth assistant*.mp. or ((location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)).mp. AND

((geographic or physical) adj5 (location* or access* or proximit* or distance*)).mp. or ((time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)).mp. or Health Services Accessibility/ or Spatial access*.mp. or “Catchment Area (Health)”/ or access to care.mp. AND Observational Study/ or exp Cohort Studies/ or Case-Control Studies/ or Cross-Sectional Studies/ or ecological stud*.mp. AND ((low or middle) adj3 (countr* or nation* or econom*)).mp. OR (Afghanistan or Benin or Burkina Faso or Burundi or Central African Republic or Chad or Comoros or Congo Democratic Republic or Eritrea or Ethiopia or Gambia or Guinea or Guinea-Bissau or Haiti or Korea Democratic People’s Republic or Liberia or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mozambique or Nepal or Niger or Rwanda or Senegal or Sierra Leone or Somalia or South Sudan or Tanzania or Togo or Uganda or Zimbabwe or Armenia or Bangladesh or Bhutan or Bolivia or Cabo Verde or Cambodia or Cameroon or Congo Republic or Ivory Coast or Djibouti or Egypt or El Salvador or Ghana or Guatemala or Honduras or India or Indonesia or Kenya or Kiribati or Kosovo or Kyrgyz Republic or Lao PDR or Lesotho or Mauritania or Micronesia Federation or Moldova or Mongolia or Morocco or Myanmar or Nicaragua or Nigeria or Pakistan or Papua New Guinea or Philippines or Samoa or Sao Tome) and Principe) or Solomon Islands or Sri Lanka or Sudan or Swaziland or Syrian Arab Republic or Tajikistan or Timor-Leste or Tonga or Tunisia or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vanuatu or Vietnam or West Bank) and Gaza) or Yemen Republic or Zambia or Albania or Algeria or American Samoa or Angola or Argentina or Azerbaijan or Belarus or Belize or Bosnia) and Herzegovina) or Botswana or Brazil or Bulgaria or China or Colombia or Costa Rica or Cuba or Dominica or Dominican Republic or Equatorial Guinea or Ecuador or Fiji or Gabon or Georgia or Grenada or Guyana or Iran or Iraq or Jamaica or Jordan or Kazakhstan or Lebanon or Libya or Macedonia or Malaysia or Malaysia or Maldives or Marshall Islands or Mauritius or Mexico or Montenegro or Namibia or Palau or Panama or Paraguay or Peru or Romania or Russian Federation or Serbia or South Africa or Saint Lucia or Saint Vincent) and the Grenadines) or Suriname or Thailand or Turkey or Turkmenistan or Tuvalu or Venezuela).mp |

| Embase | Midwifery.mp. OR midwife/ OR Maternal Health Services.mp.OR health service/ OR perinatal care/ OR obstetric delivery/ OR labor complication/ OR labor/ OR cesarean section/ OR obstetrics/ OR Parturition.mp. OR birth/ or childbirth/ OR obstetric procedure/ OR maternal care/ OR delivery/ OR Delivery care.mp. OR Delivery assistant*.mp. OR Birth assistant*.mp. OR ((location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)).mp. OR Delivery care.mp. AND

((geographic or physical) adj5 (location* or access* or proximit* or distance*)).mp. OR ((time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)).mp. ORHealth Services Accessibility.mp. OR health care access/ OR Spatial access.mp. OR Access to care.mp. AND case control study/ or observational study/ or cohort analysis/ OR cross-sectional study/ OR Ecological stud*.mp. AND ((low or middle) adj3 (countr* or nation* or econom*)).mp. OR (Afghanistan or Benin or Burkina Faso or Burundi or Central African Republic or Chad or Comoros or Congo Democratic Republic or Eritrea or Ethiopia or Gambia or Guinea or Guinea-Bissau or Haiti or Korea Democratic People’s Republic or Liberia or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mozambique or Nepal or Niger or Rwanda or Senegal or Sierra Leone or Somalia or South Sudan or Tanzania or Togo or Uganda or Zimbabwe or Armenia or Bangladesh or Bhutan or Bolivia or Cabo Verde or Cambodia or Cameroon or Congo Republic or Ivory Coast or Djibouti or Egypt or El Salvador or Ghana or Guatemala or Honduras or India or Indonesia or Kenya or Kiribati or Kosovo or Kyrgyz Republic or Laos or Lesotho or Mauritania or Micronesia Federation or Moldova or Mongolia or Morocco or Myanmar or Nicaragua or Nigeria or Pakistan or Papua New Guinea or Philippines or Samoa or Sao Tome) and Principe) or Solomon Islands or Sri Lanka or Sudan or Swaziland or Syrian Arab Republic or Tajikistan or Timor-Leste or Tonga or Tunisia or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vanuatu or Vietnam or West Bank) and Gaza) or Yemen Republic or Zambia or Albania or Algeria or American Samoa or Angola or Argentina or Azerbaijan or Belarus or Belize or Bosnia) and Herzegovina) or Botswana or Brazil or Bulgaria or China or Colombia or Costa Rica or Cuba or Dominica or Dominican Republic or Equatorial Guinea or Ecuador or Fiji or Gabon or Georgia or Grenada or Guyana or Iran or Iraq or Jamaica or Jordan or Kazakhstan or Lebanon or Libya or Macedonia or Malaysia or Malaysia or Maldives or Marshall Islands or Mauritius or Mexico or Montenegro or Namibia or Palau or Panama or Paraguay or Peru or Romania or Russian Federation or Serbia or South Africa or Saint Lucia or Saint Vincent) and the Grenadines) or Suriname or Thailand or Turkey or Turkmenistan or Tuvalu or Venezuela).mp |

| PsycINFO | exp MIDWIFERY/ OR exp Birth/ or Maternal Health Service*.mp. OR Perinatal Care.mp. OR exp Obstetrical Complications/ or exp Obstetrics/ or exp “Labor (Childbirth)”/ or exp Caesarean Birth/ or Delivery, Obstetric.mp. OR exp Obstetrical Complications/ OR Parturition.mp. OR Obstetric care.mp. OR Delivery care.mp. OR Delivery assistant*.mp. OR Birth assistant*.mp. OR ((location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)).mp. AND

((geographic or physical) adj5 (location* or access* or proximit* or distance*)).mp. OR ((time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)).mp. OR Health Services Accessibility.mp. OR Spatial access*.mp. OR Access to care.mp. AND Observational Study.mp. OR Cohort Study.mp. OR Case-Control Studies.mp. OR Cross-Sectional Studies.mp. OR Ecological studies.mp. AND ((low or middle) adj3 (countr* or nation* or econom*)).mp. OR (Afghanistan or Benin or Burkina Faso or Burundi or Central African Republic or Chad or Comoros or Congo Democratic Republic or Eritrea or Ethiopia or Gambia or Guinea or Guinea-Bissau or Haiti or Korea Democratic People’s Republic or Liberia or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mozambique or Nepal or Niger or Rwanda or Senegal or Sierra Leone or Somalia or South Sudan or Tanzania or Togo or Uganda or Zimbabwe or Armenia or Bangladesh or Bhutan or Bolivia or Cabo Verde or Cambodia or Cameroon or Congo Republic or Ivory Coast or Djibouti or Egypt or El Salvador or Ghana or Guatemala or Honduras or India or Indonesia or Kenya or Kiribati or Kosovo or Kyrgyz Republic or Laos or Lesotho or Mauritania or Micronesia Federation or Moldova or Mongolia or Morocco or Myanmar or Nicaragua or Nigeria or Pakistan or Papua New Guinea or Philippines or Samoa or Sao Tome) and Principe) or Solomon Islands or Sri Lanka or Sudan or Swaziland or Syrian Arab Republic or Tajikistan or Timor-Leste or Tonga or Tunisia or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vanuatu or Vietnam or West Bank) and Gaza) or Yemen Republic or Zambia or Albania or Algeria or American Samoa or Angola or Argentina or Azerbaijan or Belarus or Belize or Bosnia) and Herzegovina) or Botswana or Brazil or Bulgaria or China or Colombia or Costa Rica or Cuba or Dominica or Dominican Republic or Equatorial Guinea or Ecuador or Fiji or Gabon or Georgia or Grenada or Guyana or Iran or Iraq or Jamaica or Jordan or Kazakhstan or Lebanon or Libya or Macedonia or Malaysia or Malaysia or Maldives or Marshall Islands or Mauritius or Mexico or Montenegro or Namibia or Palau or Panama or Paraguay or Peru or Romania or Russian Federation or Serbia or South Africa or Saint Lucia or Saint Vincent) and the Grenadines) or Suriname or Thailand or Turkey or Turkmenistan or Tuvalu or Venezuela).mp |

| Maternity & Infant Care | Midwifery.mp. OR Maternal Health Services.mp. OR Perinatal Care.mp. OR Delivery, Obstetric.mp. OR Labor, Obstetric.mp. OR Caesarean Section.mp. OR Obstetrics.mp. OR (Parturition or childbirth).mp. OR (Obstetric care or delivery care).mp. OR (Delivery assistant* or birth assistant*).mp. OR ((location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)).mp. AND

((geographic or physical) adj5 (location* or access* or proximit* or distance*)).mp. OR ((time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)).mp. OR (Health Services Accessibility or Spatial access*).mp. OR Access to care.mp. AND Observational Study.mp. OR Cohort Studies.mp. OR Case-Control Studies.mp. OR Cross-Sectional Studies.mp. OR Ecological stud*.mp. AND ((low or middle) adj3 (countr* or nation* or econom*)).mp. OR (Afghanistan or Benin or Burkina Faso or Burundi or Central African Republic or Chad or Comoros or Congo Democratic Republic or Eritrea or Ethiopia or Gambia or Guinea or Guinea-Bissau or Haiti or Korea Democratic People’s Republic or Liberia or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mozambique or Nepal or Niger or Rwanda or Senegal or Sierra Leone or Somalia or South Sudan or Tanzania or Togo or Uganda or Zimbabwe or Armenia or Bangladesh or Bhutan or Bolivia or Cabo Verde or Cambodia or Cameroon or Congo Republic or Ivory Coast or Djibouti or Egypt or El Salvador or Ghana or Guatemala or Honduras or India or Indonesia or Kenya or Kiribati or Kosovo or Kyrgyz Republic or Laos or Lesotho or Mauritania or Micronesia Federation or Moldova or Mongolia or Morocco or Myanmar or Nicaragua or Nigeria or Pakistan or Papua New Guinea or Philippines or Samoa or Sao Tome) and Principe) or Solomon Islands or Sri Lanka or Sudan or Swaziland or Syrian Arab Republic or Tajikistan or Timor-Leste or Tonga or Tunisia or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vanuatu or Vietnam or West Bank) and Gaza) or Yemen Republic or Zambia or Albania or Algeria or American Samoa or Angola or Argentina or Azerbaijan or Belarus or Belize or Bosnia) and Herzegovina) or Botswana or Brazil or Bulgaria or China or Colombia or Costa Rica or Cuba or Dominica or Dominican Republic or Equatorial Guinea or Ecuador or Fiji or Gabon or Georgia or Grenada or Guyana or Iran or Iraq or Jamaica or Jordan or Kazakhstan or Lebanon or Libya or Macedonia or Malaysia or Malaysia or Maldives or Marshall Islands or Mauritius or Mexico or Montenegro or Namibia or Palau or Panama or Paraguay or Peru or Romania or Russian Federation or Serbia or South Africa or Saint Lucia or Saint Vincent) and the Grenadines) or Suriname or Thailand or Turkey or Turkmenistan or Tuvalu or Venezuela).mp |

| CINHAL | Midwifery” OR “Maternal Health Services” OR “Perinatal Care” OR “Delivery, Obstetric” OR “Obstetric Emergencies” OR “Labor Complications” OR “Labor” OR “Labor Support” OR “Cesarean Section, Elective” OR “Cesarean Section” OR “Parturition” OR “Childbirth” OR “Obstetric Care” OR “Delivery Care (Saba CCC)” OR “Delivery assistant*” OR “Birth Place” OR “Birth assistant*” OR ““(location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)”” OR ““(location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)”” AND

“geographic distance” OR “physical distance” OR “Geographic Locations”) OR “geographic proximit*” OR “physical proximit*” OR “physical location*” OR “geographic acess” OR “geographic acess” OR “physical access” OR ““(time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)”” OR ““(time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)”” OR “walk* time” OR “driv* time” OR “travel* time” OR “walk* distance” OR “driv* distance” OR “travel* distance” OR Health Services Accessibility”) OR (MH “Health Services Needs and Demand” ““Access to care”” OR ““Spatial access*”” OR “Catchment Area (Health)” AND “Nonexperimental Studies” OR ““Observational Study”” OR “Cross Sectional Studies”) OR ““Cohort Studies”” OR “Case Control Studies” OR ““Ecological stud*”” AND “Low and Middle Income Countries”) OR “Afghanistan or Benin or “Burkina Faso” or Burundi or “Central African Republic” or Chad or Comoros or “Congo Democratic Republic” or Eritrea or Ethiopia or Gambia or Guinea or Guinea-Bissau or Haiti or “Korea Democratic People’s Republic” or Liberia or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mozambique or Nepal or Niger or Rwanda or Senegal or “Sierra Leone” or Somalia or “South Sudan” or Tanzania or Togo or Uganda or Zimbabwe or Armenia or Bangladesh or Bhutan or Bolivia or “Cabo Verde” or Cambodia or Cameroon or “Congo Republic” or “Ivory Coast” or Djibouti or Egypt or El-Salvador or Ghana or Guatemala or Honduras or India or Indonesia or Kenya or Kiribati or Kosovo or “Kyrgyz Republic” or Laos or Lesotho or Mauritania or “Micronesia Federation” or Moldova or Mongolia or Morocco or Myanmar or Nicaragua or Nigeria or Pakistan or “Papua New Guinea” or Philippines or Samoa or “Sao Tome and Principe” or “Solomon Islands” or Sri-Lanka or Sudan or Swaziland or “Syrian Arab Republic” or Tajikistan or Timor-Leste or Tonga or Tunisia or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vanuatu or Vietnam or “West Bank and Gaza” or “Yemen Republic” or Zambia or Albania or Algeria or “American Samoa” or Angola or Argentina or Azerbaijan or Belarus or Belize or Bosnia and Herzegovina or Botswana or Brazil or Bulgaria or China or Colombia or “Costa Rica” or Cuba or Dominica or “Dominican Republic” or “Equatorial Guinea” or Ecuador or Fiji or Gabon or Georgia or Grenada or Guyana or Iran or Iraq or Jamaica or Jordan or Kazakhstan or Lebanon or Libya or Macedonia or Malaysia or Malaysia or Maldives or “Marshall Islands” or Mauritius or Mexico or Montenegro or Namibia or Palau or Panama or Paraguay or Peru or Romania or “Russian Federation” or Serbia or “South Africa” or “Saint Lucia” or “Saint Vincent and the Grenadines” or Suriname or Thailand or Turkey or Turkmenistan or Tuvalu or Venezuela” |

| Scopus | midwifery OR “Maternal Health Services” OR “Perinatal Care” OR delivery, AND obstetric OR “Obstetric Labor Complications” OR labor OR “Caesarean Section” ) OR obstetrics OR parturition OR childbirth OR “Obstetric care” OR “Delivery care” OR “Delivery assistant*” OR “Birth assistant*” OR “(location or place) adj3 (birth or delivery)” ) AND

“(geographic or physical) adj5 (location* or access* or proximit* or distance*)” OR “(time or distance*) adj5 (walk* or driv* or travel*)” ) OR “Health Services Accessibility” OR “Spatial access*” OR “Catchment Area (Health)” OR “Access to care” ) AND “Observational Study” OR “Cohort Studies” OR “Case-Control Studies” OR “Cross-Sectional Studies” OR “Ecological stud*” ) AND “(low or middle) adj3 (countr* or nation* or econom*)” OR Afghanistan OR Benin or “Burkina Faso” OR Burundi OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Comoros OR “Congo Democratic Republic” OR Eritrea or Ethiopia OR Gambia OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Haiti OR “Korea Democratic People’s Republic” OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mozambique OR Nepal OR Niger OR Rwanda OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR Somalia OR “South Sudan” OR Tanzania OR Togo OR Uganda OR Zimbabwe OR Armenia OR Bangladesh OR Bhutan OR Bolivia OR “Cabo Verde” OR Cambodia ORCameroon OR “Congo Republic” OR “Ivory Coast” OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR El-Salvador OR Ghana OR Guatemala OR Honduras OR India OR Indonesia OR Kenya OR Kiribati OR Kosovo OR “Kyrgyz Republic” OR Laos OR Lesotho OR Mauritania OR “Micronesia Federation” OR Moldova OR Mongolia ORMorocco OR Myanmar OR Nicaragua OR Nigeria OR PakistanOR “Papua New Guinea” OR Philippines OR Samoa OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR “Solomon Islands” OR Sri-Lanka OR Sudan OR Swaziland OR “Syrian Arab Republic” OR Tajikistan OR Timor-Leste OR Tonga OR Tunisia ORUkraine OR Uzbekistan OR Vanuatu OR Vietnam OR “West Bank and Gaza” OR “Yemen Republic” OR Zambia OR Albania OR Algeria OR “American Samoa” OR Angola OR Argentina ORAzerbaijan OR Belarus OR Belize OR Bosnia and Herzegovina OR Botswana OR Brazil OR Bulgaria OR China OR Colombia OR “Costa Rica” OR Cuba OR Dominica OR “Dominican Republic” OR “Equatorial Guinea” OREcuador OR Fiji OR Gabon OR Georgia ORGrenada OR Guyana ORIran OR Iraq OR Jamaica OR Jordan OR Kazakhstan OR Lebanon OR Libya OR Macedonia OR Malaysia OR Malaysia OR Maldives OR “Marshall Islands” OR Mauritius OR Mexico OR Montenegro OR Namibia OR Palau OR Panama OR Paraguay OR Peru OR Romania OR “Russian Federation” ORSerbia OR “South Africa” OR “Saint Lucia” OR “Saint Vincent and the Grenadines” OR Suriname OR Thailand OR Turkey OR Turkmenistan OR Tuvalu OR Venezuela |

| Hand search: Google Scholar | Varieties of key terms from the above-mentioned were used; and 39 papers turned out. |

Table 2: Characteristics of studies included in systematic review and meta-analysis

| Study and country | Study design and setting | Study population and sample size | Results | Geographic access on delivery care use | Remark (quality) |

| Karkee et al (2013), Nepal (27)

≥60 minutes |

Community based prospective cohort study | 644 pregnant women up to 45 days of postpartum period | 547 (85%) of them gave birth at health facility | ≤30 minute travel time was significantly associated with health facility delivery; AOR = 11.61: 5.77 – 24.04

Ref: >60minutes Inverse of ≤30 ( take Ref: ≤30 minute) >60minutes: AOR = 0.09: 0.04, 0.17 |

|

| Joshi et al (2016), Nepal (29)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 275 women who gave birth in the past 5 years | 35% had delivered at health facility | Increased institutional delivery for ≤60 minutes of travel time to nearest delivery health facility; AOR = 7.7: 4.1, 14.4

Ref: >60 minute Inverse of ≤60 (take Ref: ≤60 minutes) >60 minutes: AOR = 0.13: 0.07, 0.24 |

|

| Kawakatsu et al (2014), Kenya (41)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 2026 women who had children aged from 12-24 months | 48% were institutional delivery | ≤20 minute travel time was associated with increased institutional delivery; AOR = 2.48: 1.74 – 3.55

Ref: >60minutes Inverse of ≤20 (take Ref: ≤20 minute) >60minutes: AOR = 0.40: 0.28, 0.57 |

|

| Hailu & Berhe (2014), Ethiopia (42)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 485 women of reproductive age who gave birth in the past two years | 31.5% gave birth at health facilities | An increased institutional delivery for <60 minute of travel to nearest health facility; AOR = 3.3: 1.15 – 9.52

Ref: ≥60minutes Inverse of <60 (take Ref: <60 minute) ≥60minutes: AOR = 0.30: 0.11, 0.87 |

|

| Habte & Demissie (2015), Ethiopia (43)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 816 women who gave birth in the past two years | 31% of births were in health facility | Decreased institutional delivery for >60 minute travel time;

>60 minute; AOR = 0.22: 0.09, 0.55 Ref: <30 minute |

|

| Wagle et al (2004), Nepal (44)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 308 women who gave birth within 45 days of the survey | 50.6% of deliveries were in health facility | A traveling time of >60 minutes to a maternity hospital led to an increased odds of home delivery; AOR = 7.9; 3.7, 16.6

Ref: <60 minutes For institutional delivery – take the inverse of home delivery; AOR = 0.13: 0.06, 0.27 |

|

| Feyissa & Genemo (2014), Ethiopia (45)

≥60 minutes and ≤5km |

Unmatched case control | 320 women aged 15-49 years | 80 cases (institutional) and 240 home deliveries | ≥10 km; OR = 0.665: 0.173, 0.954

Ref: <5km Travel time: Ref; >2hour <60 minute; AOR = 3.554; 0.884, 14.283 (Not sig) Take Ref <60; then AOR for >2 hour = 0.28; 0.07, 1.13 |

|

| Worku & Alemay (2016), Ethiopia (46)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 573 women who gave birth 12 months preceding the survey | 16.9% were health facility births | Travel time to closest health facility: Ref; >2 hour

<60 minutes: AOR = 5.2; 2.8, 12.3 1 to 2 hour not significant Take ref <60: AOR for >2hr = 0.19; 0.08, 0.36 |

|

| Van et al (2006), Kenya (47)

≥60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 635 women who gave birth 12 months preceding the survey | 83% were outside health facility; of these 80%, 18% & 3% were in their house, TBA house & on the way to health facility | Travel time:

Birth outside health facility Ref: <60 minutes of walk >60 minutes of walk: AOR = 2.75; 1.33, 5.68 Take inverse of birth outside health facility to health facility delivery Ref: <60 minutes of walk >60 minutes of walk: AOR = 0.36; 0.18, 0.75 |

|

| Lwelamira et al (2012), Tanzania (48)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 984 women gave birth 2 years prior | 54% were in institutional deliveries | >10 km; OR = 0.62: 0.47, 0.81

Ref: <5km |

|

| Yanagisawa et al (2006), Cambodia (49)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 980 women aged 15-49 who gave birth within 3 months | 55.2% were health facility | Distance to Health Centre is for facility delivery; Ref: >5km

<2km; OR = 3.35; 2.10, 5.34 Distance to Hospital is for facility delivery; Ref: ≥20km <10km: OR= 3.32: 2.02, 5.45 |

|

| Gage & Guirle (2006), Haiti (50)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 4533 rural women aged 15-49 years | 9.6% were intuitional deliveries | Distance to hospital; Ref <5km

5-14 km: OR = 0.339; 0.197, 0.584 |

|

| Kesterton et al (2012), India (51)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 98777 and 90303 women aged 15-49 who had births within 3 years preceding the survey | Trend (1989 to 1998) is 15-25% | Distance to hospital: Ref: >30km

≤5km: OR = 2.43; 1.93, 3.06 |

|

| Mageda & Mmbaga (2015), Tanzania (52)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 598 women who gave birth 12 months preceding the survey | 56% were health facility births | Distance to health facility: Ref; ≥10km

<5km; OR = 2.3: 1.3, 3.9 |

|

| Faye et al (2011), Senegal (53)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 373 women who gave birth in the last 12months | 22% were home delivery | Distance to health centre; Home births

>5km; OR = 2.24; 1.21, 4.15 Ref: ≤5km |

|

| Anyait et al (2012), Uganda (12)

≤5km |

Community based cross-section study | 500 women who gave birth in the past two years | 45.4% delivered in health facility | Having access to obstetric care facility within 3km is not associated with facility delivery

Crude OR = 1.9: 1.2, 3.1; No Confidence interval for AOR |

|

| De Allegri et al (2011), Burkina Faso (28)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 435 women reported pregnant 12 months prior to the survey | 72% were health facility delivery | Having access to obstetric care facility within 5km increased institutional delivery; AOR = 28.42, Robust Standard Error = 11.90; No Confidence interval for AOR |

|

| Kitui et al (2013), Kenya (13)

≤5km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 3967 women aged 15-49 who had births within 5 years preceding the survey | 46.8% were health facility births | Distance to health facility: AOR not significant

2-5km: COR: 0.5: 0.46, 0.68 Ref: <2km Confidence interval not given for AOR |

|

| De Allegri et al (2015), Burkina Faso (35)

Ref ≤6km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 420 women of recent history of childbirth | 11% of home delivery | A distance of ≥7 km was significantly associated with an increased in home delivery; AOR = 19.33; 3.37, 110.88

Ref ≤6km |

|

| Jain et al (2015), Pakistan (25)

≤10km and 1km increase |

Cross-sectional study, Linked health facility & household survey | 763 obstetric care facilities and 4435 women who gave birth three years before the survey | 21.0% of women had no access to delivery care facility within 10 kilometre |

|

|

| Ogolla (2015), Kenya (34)

≤10km |

Community based cross-sectional study | 600 women aged 15-49 who had births within 6 months prior | 33.3% were health facility births | Distance to nearest health facility; Ref: ≤10km

>10 km; OR = 0.5: 0.3, 0.7 |

|

| Zegeye et al (2014), Ethiopia (9)

1km increase |

Community based cross-sectional study | 528 women who gave birth preceding the survey | 8% of mothers gave birth in health facility | A 22% decrease in institutional delivery per one kilometre increase in walking distance to the nearest health centre; AOR = 0.78 (0.64, 0.96) |

|

| Joharifard et al (2012), Rwanda (31)

1km increase |

Community based cross-sectional study – Trend analysis | 3106 lifetime deliveries from 895 women (18-50 years of age and gave birth within three years) | 89.8% of them delivered in health facility | Facility delivery decreased per a single kilometre increase in distance to the closest health facility; AOR = 0.909 (0.846, 0.976) |

|

| Kumar et al (2014), India (32)

1km increase |

Community based cross-sectional study | 158897 women aged 15-49 years | 36% were institutional births | A one kilometre increase in distance is associated with a 4.4% decrease in health facility delivery

No CI for AOR or COR |

|

| Hounton et al (2008), Burkina Faso (33)

1km increase |

Community & health facility based cross-sectional study | 43 Health Facilities & census of women aged 12-49 | 81536 births; 3145 (38.4%) were institutional births | Institutional birth decrease with…

Odds ratio/km; distance to health centre 0.77/km (<7.5km) & 0.97/km (≥7.5km) Distance to hospital; Odds ratio/10km = 0.83 |

|

| Lohela et al (2012), Malawi and Zambia (7)

10km increase |

Cross-sectional study, linked analysis (Household survey (HHS) and health facility assessment (SPA)) | 8537 births (firstborn were included in case of multiple births )

8842 total births 446 health facilities |

Half of the births were in health facility | Health facility delivery decreased by 65% for every 10 km increase in distance; AOR = 0.35 (Malawi) |

|

| 3682 births (firstborn were included in case of multiple births )

3771 total births 1131 health facilities |

32.5% of births were in health facility | Health facility delivery decreased by 27% for every 10 km increase in distance; AOR = 0.73 (Zambia) | |||

| Gabrysch et al (2011), Zambia (6)

Doubling distance |

Cross-sectional study, linked analysis (HHS & SPA) | 3682 births (firstborn were included in case of multiple births) 1131 health facilities | 32.5% births were health facility | A 29% decrease in odds of facility delivery for every doubling of distance |

|

| Masters et al (2013), Ghana (26)

1hr increase |

Cross-sectional study; Linked population and health facility data | 1172 mothers, and 1646 births, and 1268 facilities | 39.0% were in facility deliveries | An increase in travel time of one hour decreased the odds of facility delivery by 20%; AOR = 0.80: 0.69, 0.93 |

|

| Teferra et al (2012), Ethiopia (10)

<60 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 371 women who gave birth 12 months preceding the survey | 12.1% were health facility births | Travel time to closest health facility: AOR not significant

<60 minutes: COR = 6.2; 1.87, 20.5 Ref: ≥60 minute Take <60 minute as Ref COR for ≥60 minute = 0.16; 0.05, 0.53; AOR not given |

|

| Amano et al (2012), Ethiopia (11)

≤30 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 855 women who gave birth 12 months preceding the survey | 12.3% were health facility births | Travel time to closest health facility: AOR not significant

≤30 minutes: COR = 2.04; 1.26, 3.30 Ref: >30 minute AOR not given |

|

| Shimazaki et al (2013), Philippines (30)

≤30 minutes |

Community based cross-sectional study | 354 women who gave birth in the 3 years | 44.4% were HF delivery | Time taken to nearest HF; Ref: ≥31minutes

11-30 minutes; OR = 3.3; 1.7, 6.6 ≤10minutes: OR = 6.9; 3.4, 14.2 |

|

References

1. Wang W, Winter R, Mallick L, et al. The Relationship between the Health Service Environment and Service Utilization: Linking Population Data to Health Facilities Data in Haiti and Malawi. DHS Analytical Studies No. 51. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International; 2015.

2. Fortney JC, Burgess JF, Bosworth HB, et al. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):639.

3. Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, et al. Poverty and access to health care in developing countries. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1136(1):161-71.

4. Burgert-Brucker CR, Prosnitz D. Linking DHS household and SPA facility surveys: Data considerations and Geospatial Methods. DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 10: ICF International; 2014.

5. Baker JB, Liu L. The determinants of primary health care utilization: a comparison of three rural clinics in Southern Honduras. GeoJournal. 2006;66(4):295-310.

6. Gabrysch S, Cousens S, Cox J, et al. The influence of distance and level of care on delivery place in rural Zambia: a study of linked national data in a geographic information system. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000394.

7. Lohela TJ, Campbell OM, Gabrysch S. Distance to care, facility delivery and early neonatal mortality in Malawi and Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52110.

8. Wang W, Winner M, Burgert C, et al. Influence of service readiness on use of facility delivery care: a study linking health facility data and population data in Haiti. DHS Working Papers No. 114. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF International; 2014.

9. Zegeye K, Gebeyehu A, Melese T. The role of geographical access in the Utilization of institutional delivery service in rural Jimma Horro District, Southwest Ethiopia. Prim Health Care. 2014;4(1):2167-1079.1000150.

10. Teferra AS, Alemu FM, Woldeyohannes SM. Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months in Sekela District, North West of Ethiopia: A community – based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2012;12:74.

11. Amano A, Gebeyehu A, Birhanu Z. Institutional delivery service utilization in Munisa Woreda, South East Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2012;12:105.

12. Anyait A, Mukanga D, Oundo GB, et al. Predictors for health facility delivery in Busia district of Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):132-.

13. Kitui J, Lewis S, Davey G. Factors influencing place of delivery for women in Kenya: an analysis of the Kenya demographic and health survey, 2008/2009. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2013;13:40.

14. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis: Sage publications Thousand Oaks, CA; 2001.

15. The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Country Classification 2017 [Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

16. Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, et al. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. International journal of evidence-based healthcare. 2015;13(3):147-53.

17. The Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual. 2016 ed. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2016.

18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

19. Wilunda C, Quaglio G, Putoto G, et al. Determinants of utilisation of antenatal care and skilled birth attendant at delivery in South West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):1-12.

20. Mayhew M, Hansen PM, Peters DH, et al. Determinants of Skilled Birth Attendant Utilization in Afghanistan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1849–56.

21. Alemayehu M, Mekonnen W. The Prevalence of Skilled Birth Attendant Utilization and Its Correlates in North West Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:436938.

22. Mpembeni RN, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, et al. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:29.

23. Peltzer K, Mosala T, Shisana O, et al. Utilization of delivery services in the context of prevention of HIV from mother-to-child (PMTCT) in a rural community, South Africa. Curationis. 2006;29(1):54-61.

24. Wado YD, Afework MF, Hindin MJ. Unintended pregnancies and the use of maternal health services in southwestern Ethiopia. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2013;13 (1) (no pagination)(36).

25. Jain AK, Sathar ZA, ul Haque M. The constraints of distance and poverty on institutional deliveries in Pakistan: Evidence from georeference-linked data. Studies in Family Planning. 2015;46(1):21-39.

26. Masters SH, Burstein R, Amofah G, et al. Travel time to maternity care and its effect on utilization in rural Ghana: A multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:147-54.

27. Karkee R, Binns CW, Lee AH. Determinants of facility delivery after implementation of safer mother programme in Nepal: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):193-.

28. De Allegri M, Ridde V, Louis VR, et al. Determinants of utilisation of maternal care services after the reduction of user fees: A case study from rural Burkina Faso. Health Policy. 2011;99(3):210-8.

29. Joshi D, Baral S, Giri S, et al. Universal institutional delivery among mothers in a remote mountain district of Nepal: what are the challenges? Public Health Action. 2016;6(4):267-72.

30. Shimazaki A, Honda S, Dulnuan MM, et al. Factors associated with facility-based delivery in Mayoyao, Ifugao Province, Philippines. Asia Pacific family medicine. 2013;12(1):5.

31. Joharifard S, Rulisa S, Niyonkuru F, et al. Prevalence and predictors of giving birth in health facilities in Bugesera District, Rwanda. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1049-.

32. Kumar S, Dansereau EA, Murray CJL. Does distance matter for institutional delivery in rural India? Applied Economics. 2014;46(33):4091-103.

33. Hounton S, Chapman G, Menten J, et al. Accessibility and utilisation of delivery care within a Skilled Care Initiative in rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13 Suppl 1:44-52.

34. Ogolla JO. Factors Associated with Home Delivery in West Pokot County of Kenya. Advances in Public Health. 2015;2015:1-6.

35. De Allegri M, Tiendrebéogo J, Müller O, et al. Understanding home delivery in a context of user fee reduction: a cross-sectional mixed methods study in rural Burkina Faso. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:1-13.

36. Pun-Cheng LSC. Distance Decay. In: Douglas Richardson NC, Michael F. Goodchild, Audrey Kobayashi, Weidong Liu, and Richard A. Marston., editor. The International Encyclopedia of Geography John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. p. 1-5.

37. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091-110.

38. Organization WH. Background paper for the technical consultation on effective coverage of health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2001.

39. The World Bank and Ministry of Health Ethiopia (2005) A Country Status Report on Health and Poverty (In Two Volumes) Volume II: Main Report.

40. Health and Places Initiative. Geographic Healthcare Access and Place. A Research Brief. 2014;1.

41. Kawakatsu Y, Sugishita T, Oruenjo K, et al. Determinants of health facility utilization for childbirth in rural western Kenya: cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:265.

42. Hailu D, Berhe H. Determinants of institutional childbirth service utilisation among women of childbearing age in urban and rural areas of Tsegedie district, Ethiopia. Midwifery. 2014;30(11):1109-17.

43. Habte F, Demissie M. Magnitude and factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization among childbearing mothers in Cheha district, Gurage zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:1-12.

44. Wagle RR, Sabroe S, Nielsen BB. Socioeconomic and physical distance to the maternity hospital as predictors for place of delivery: an observation study from Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2004;4:2004. 10.

45. Feyissa TR, Genemo GA. Determinants of institutional delivery among childbearing age women in Western Ethiopia, 2013: unmatched case control study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97194.

46. Worku Brhanie T, Alemay Anteneh H. Level of Institutional Delivery Service Utilization and Associated Factors among Women who Gave Birth in the Last One Year in Gonji Kollela District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Cross-Sectional Study. Primary Health Care Open Access. 2016;6(3).

47. Van Eijk AM, Bles HM, Odhiambo F, et al. Use of antenatal services and delivery care among women in rural western Kenya: a community based survey. Reprod Health. 2006;3:2.

48. Lwelamira J, Safari J. Choice of Place for Childbirth: Prevalence and Determinants of Health Facility Delivery Among Women in Bahi District, Central Tanzania. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences 2012;4(3):105-12.

49. Yanagisawa S, Oum S, Wakai S. Determinants of skilled birth attendance in rural Cambodia. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(2):238-51.

50. Gage AJ, Guirlene Calixte M. Effects of the physical accessibility of maternal health services on their use in rural Haiti. Popul Stud (Camb). 2006;60(3):271-88.

51. Kesterton AJ, Cleland J, Sloggett A, et al. Institutional delivery in rural India: the relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2010;10:30.

52. Mageda K, Mmbaga EJ. Prevalence and predictors of institutional delivery among pregnant mothers in Biharamulo district, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:51.

53. Faye A, Niane M, Ba I. Home birth in women who have given birth at least once in a health facility: contributory factors in a developing country. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(11):1239-43.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "International Studies"

International Studies relates to the studying of economics, politics, culture, and other aspects of life on an international scale. International Studies allows you to develop an understanding of international relations and gives you an insight into global issues.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: