Impact of Effective Human Resource Management in International Companies

Info: 35319 words (141 pages) Dissertation

Published: 19th Aug 2021

Abstract

Human resource management affects every aspect of the workforce: management/ labor, employer/employee, student/professional. This thesis provides coverage of all the expected HRM critical topics such as analyzing jobs; planning; recruiting, selecting, training, developing, and compensating employees; managing performance; and handling labor relations. In addition, I tried to define ways to achieve extraordinary results in international organizations. The additional expectations of the proactive human resource professional and leader, such as managing human resources globally, adopting a total rewards approach to compensating and rewarding employees, and creating a high-performance work environment where employees hearts and minds are engaged.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements.....................................................2

Table of Contents...................................................5

Table of Figures.....................................................8

Introduction........................................................10

Strategies, Trends, and Challenges in Human Resource Management..........12

The Value of People...................................................12

Responsibilities of Human Resource Departments...........................15

Analysing and Designing Jobs........................................17

Recruiting and Hiring Employees......................................17

Training and Developing Employees...................................18

Managing Performance..............................................19

Compensation and Rewards..........................................19

Maintaining Positive Employee and Labour Relations......................20

Establishing and Administering Human Resource Policies..................20

Ensuring Compliance with Legislation..................................20

Focus on Strategy.....................................................21

Productivity Improvement............................................22

Expanding into Global Markets........................................22

The Global Workforce.................................................23

International Assignments............................................24

Outsourcing.......................................................24

Mergers and Acquisitions............................................25

Required Professional Capabilities (RPCs) and Certification of HR

Professionals......................................................26

Ethics in Human Resource Management...................................27

Code of Ethics.....................................................28

HR Responsibilities of Supervisors and Line Managers.......................29

Careers in Human Resource Management..................................30

Change in the Labour Force.............................................32

Change in the Employment Relationship...................................35

A New Psychological Contract........................................35

Flexibility........................................................36

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL

COMPANIES..............................................................37

Preparing for and Acquiring Human Resources...........................39

Work Flow in Organizations..........................................39

Work Flow Analysis................................................39

Work Flow Design and Organization's Structure..........................41

Job Analysis.........................................................42

Job Descriptions...................................................43

Writing a Job Description............................................43

Job Specifications..................................................46

Fleishman Job Analysis System.......................................47

Written Comprehension..............................................48

Importance of Job Analysis...........................................49

Job Design..........................................................50

Designing Efficient Jobs.............................................50

Designing Jobs That Motivate.........................................51

Self-Managing Work Teams..........................................53

Flexible Work Schedules.............................................54

Managing Talent.....................................................56

Training and Development Linked to Organizational Needs and Strategy.........58

Needs Assessment and Assessing Readiness for Training......................60

Organization Analysis...............................................61

Person Analysis....................................................62

Task Analysis.....................................................63

In-House or Contracted Out?..........................................63

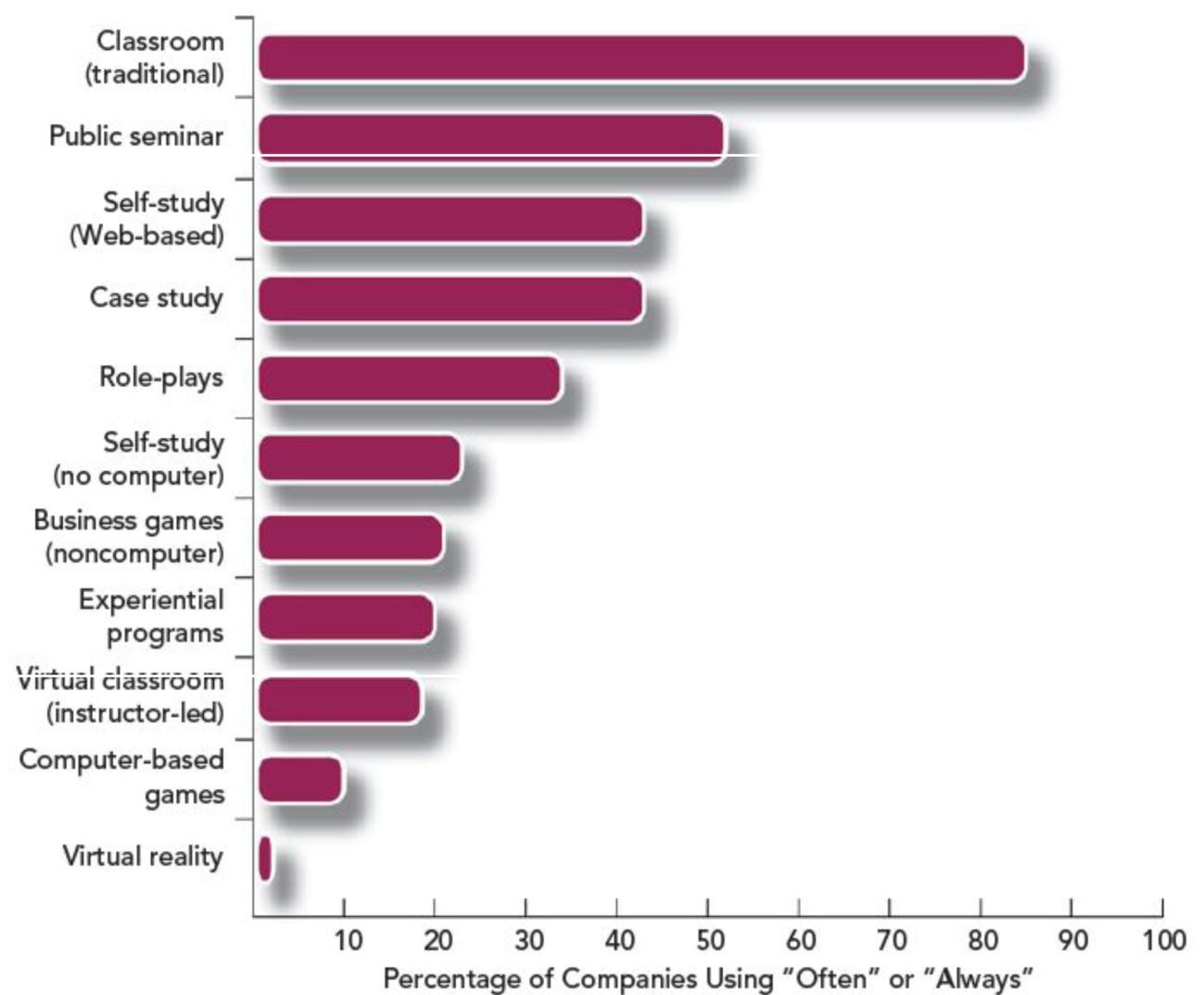

Choice of Training Methods............................................64

Classroom Instruction...............................................66

Audio-visual Training...............................................66

Computer-Based Training............................................66

Electronic Performance Support Systems................................67

E-Learning........................................................67

Implementing and Evaluating the Training Program..........................68

Principles of Learning...............................................68

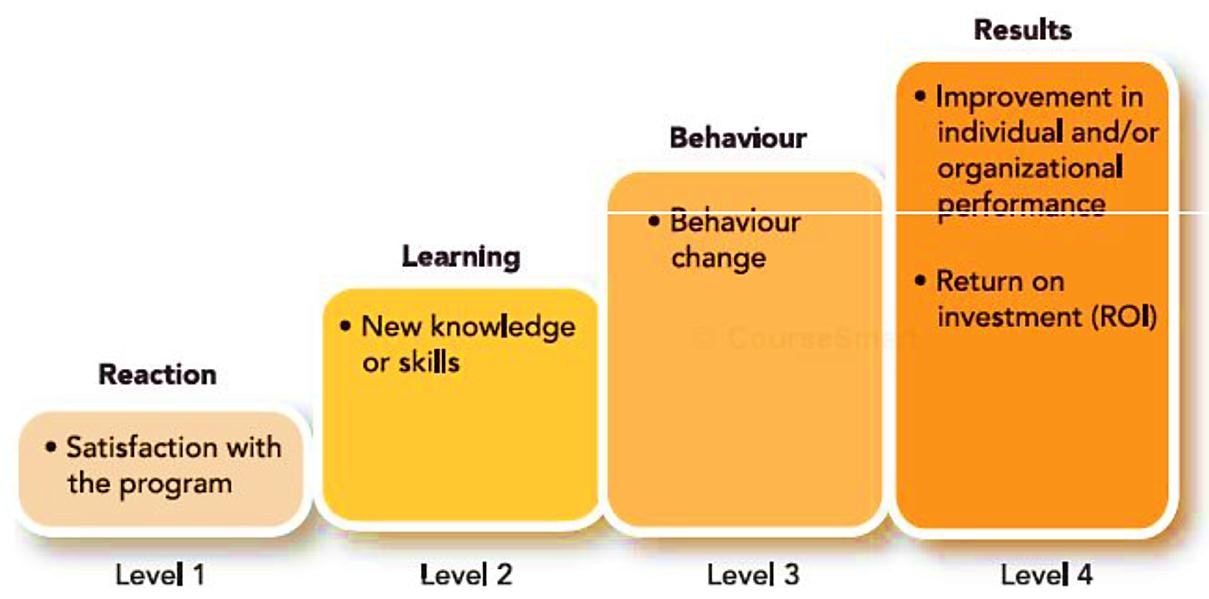

Measuring Results of Training...........................................71

Evaluation Methods.................................................72

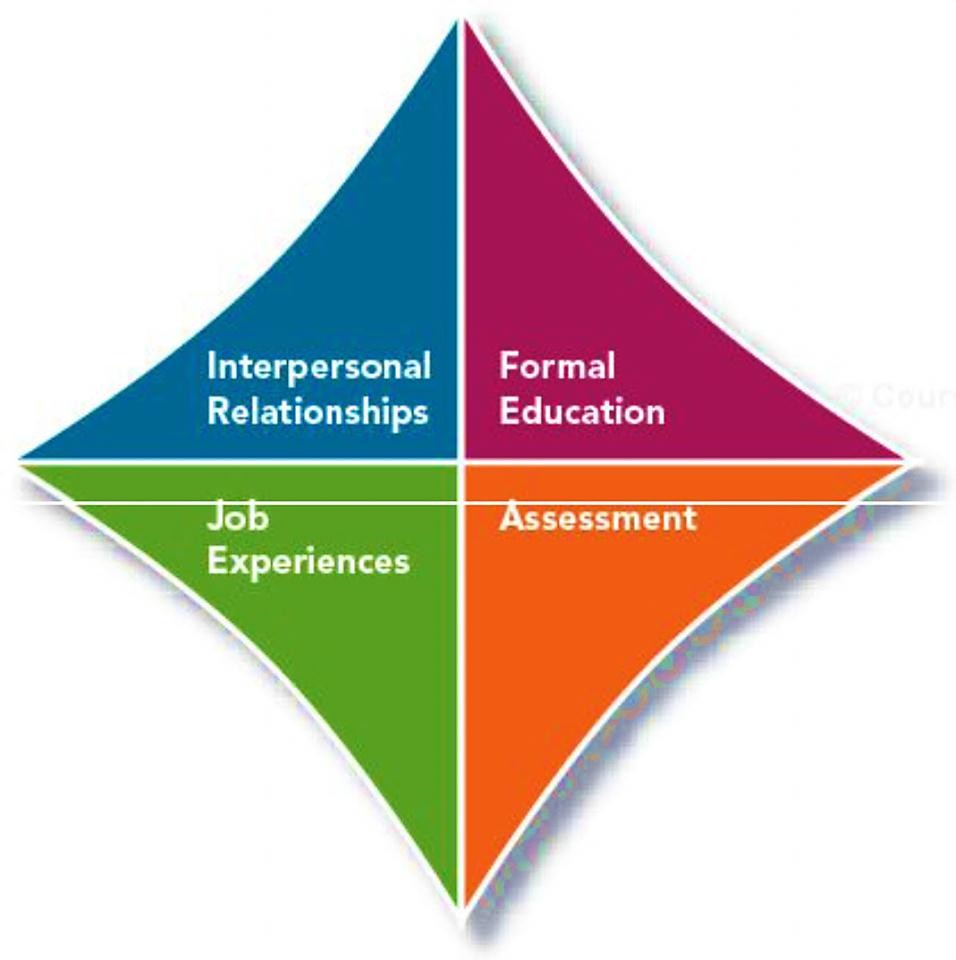

Approaches to Employee Development...................................73

Development for Careers.............................................74

Formal Education..................................................75

Assessment.......................................................76

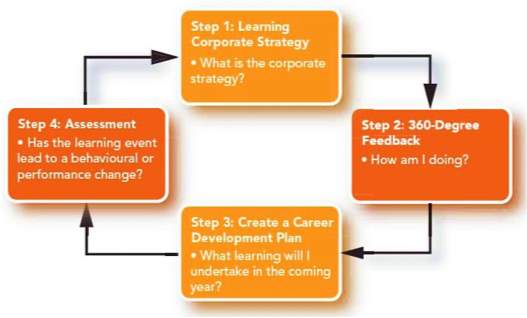

360-Degree Feedback................................................77

Managing Human Resources Globally...................................79

International Workforce.............................................80

Employers in the Global Marketplace...................................81

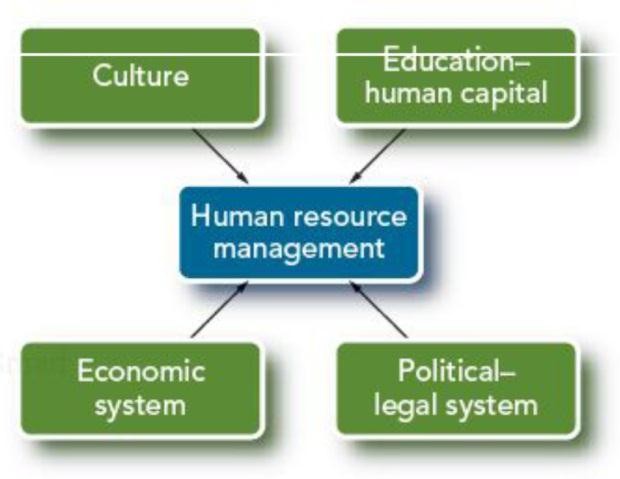

Factors Affecting HRM in International Markets...........................84

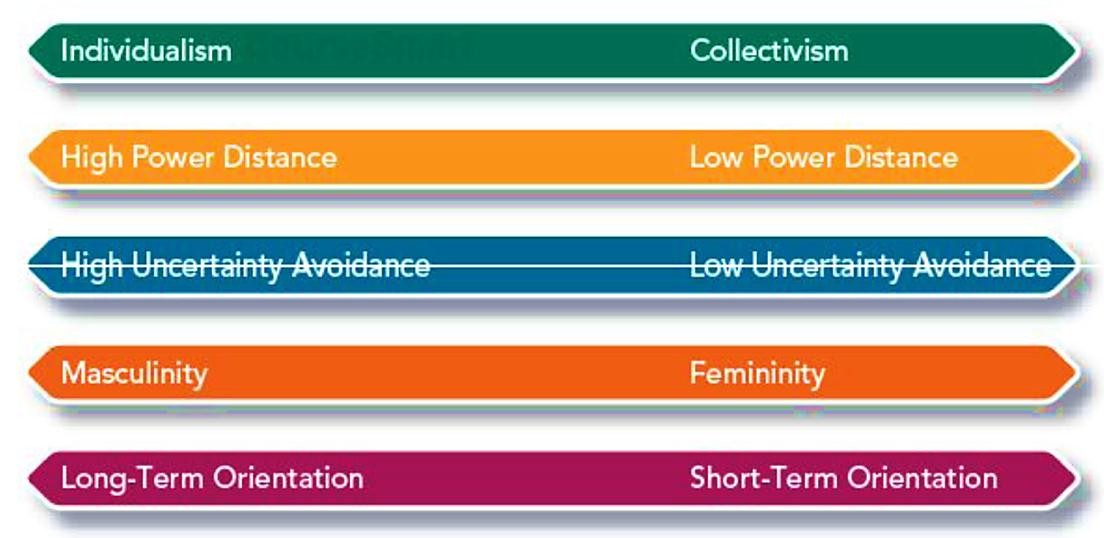

Culture...........................................................85

Education and Skill Levels...........................................90

Economic System..................................................90

Political-Legal System...............................................91

Workforce Planning in a Global Economy................................92

Selecting Employees in a Global Labour Market...........................93

Training and Developing a Global Workforce..............................95

Training Programs for an International Workforce.........................96

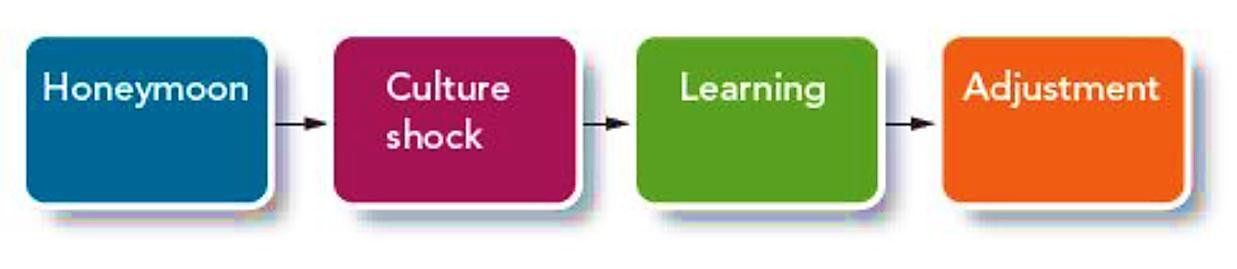

Cross-Cultural Preparation.............................................98

Performance Management across National Boundaries........................99

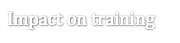

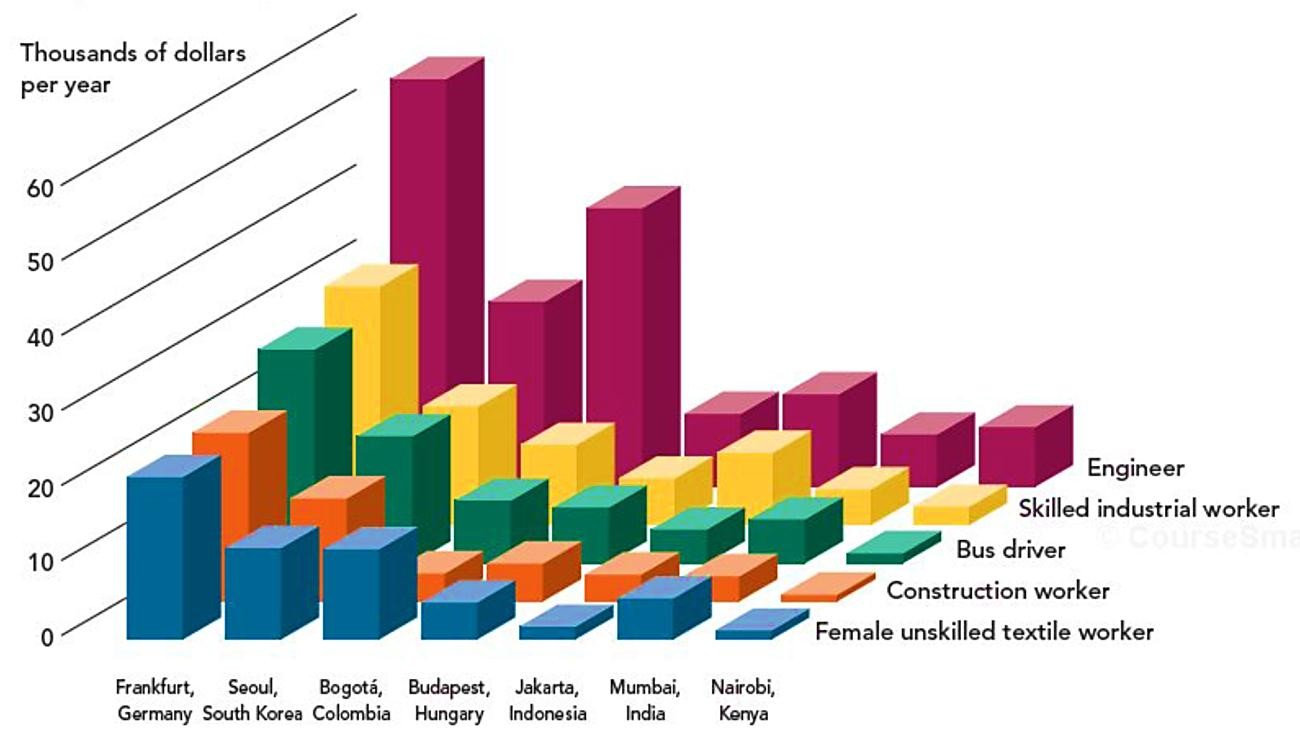

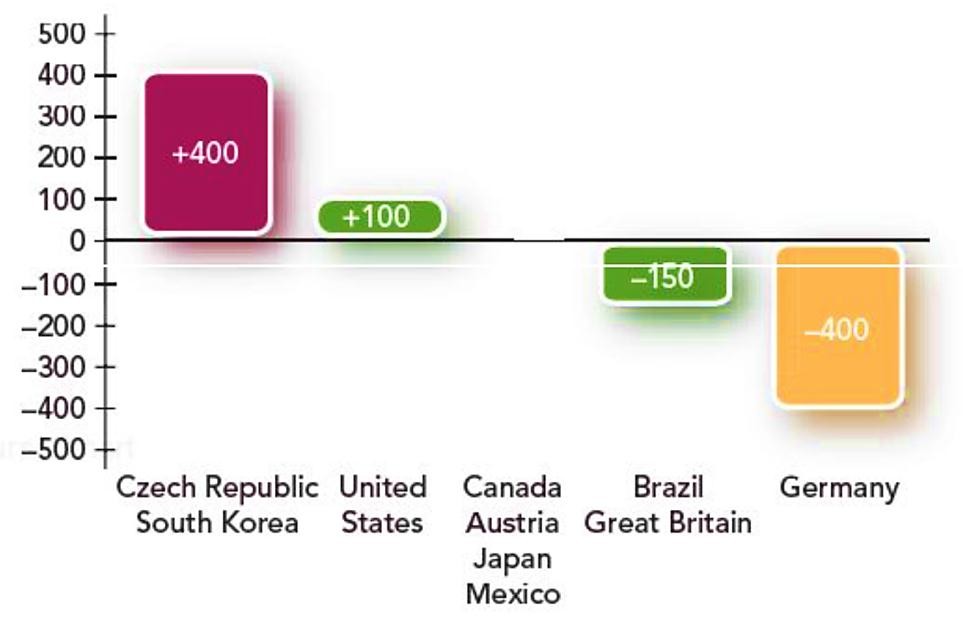

Compensating and Rewarding an International Workforce....................100

Pay Structure.....................................................100

Employee Benefits.................................................102

Preparing Expatriates................................................103

Conclusion.........................................................108

Bibliography........................................................111

Table of Figures

FIGURE 1 : HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES........................................11

FIGURE 2 : IMPACT OF HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT........................................13

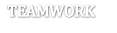

FIGURE 3 : AVERAGE LABEL PRODUCTIVITY GROWTH (%)......................................23

FIGURE 4 : REQUIRED PROFESSIONAL CAPABILITIES BY FUNCTIONAL DIMENSIONS......................26

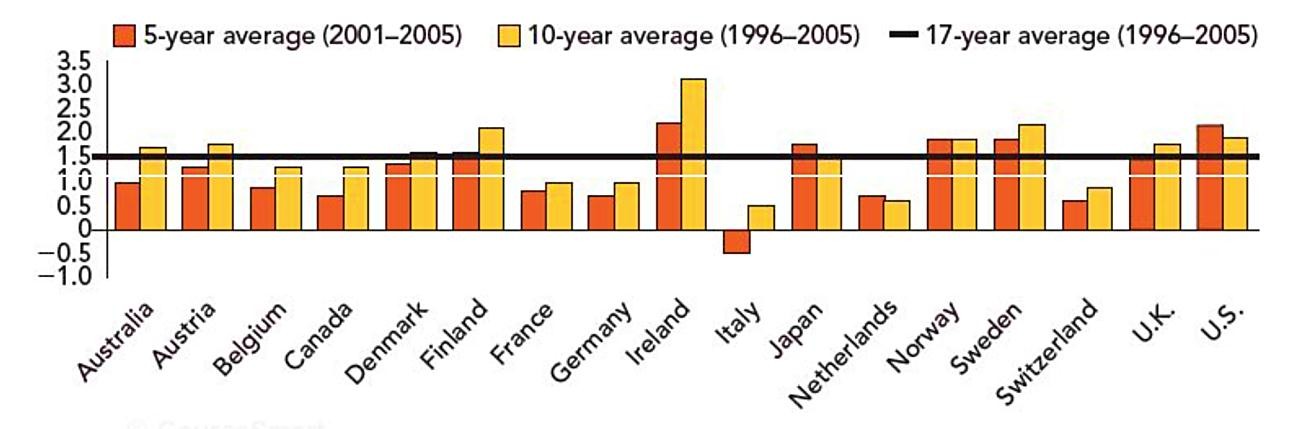

FIGURE 5 : STANDARDS FOR IDENTIFYING ETHICAL PRACTICES................................27

FIGURE 6 : TYPICAL AREAS OF INVOLVEMENTS..............................................30

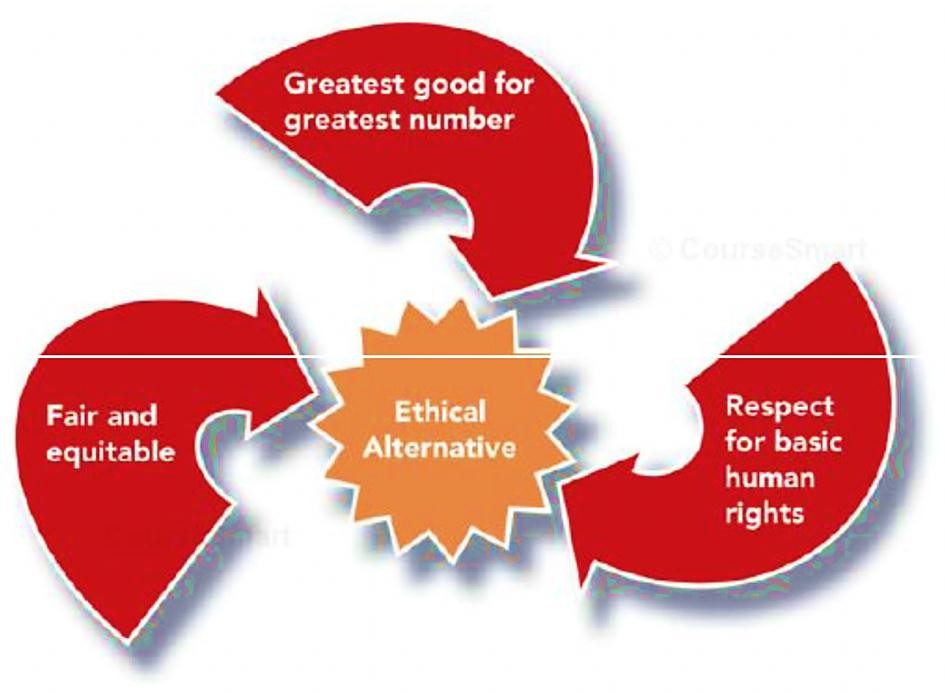

FIGURE 7 : SALARIES FOR HRM POSITIONS.......................................................31

FIGURE 8 : AVERAGE HOURLY EARNINGS IN HR....................................................31

FIGURE 9 : DECLINE OF LABOUR FORCE..........................................................33

FIGURE 10 : AGE DISTRIBUTION PROJECTION OF THE EUROPEAN POPULATION....................33

FIGURE 11 : HRM PRACTICES THAT SUPPORT DIVERSITY MANAGEMENT.....................34

FIGURE 12 : DEPLOYING A WORK-UNIT ACTIVITY ANALYSIS.........................................40

FIGURE 13 : EXAMPLE OF ABILITY FROM THE FLEISHMAN JOB ANALYSIS SYSTEM.................48

FIGURE 14 : APPROACHES TO JOB DESIGN........................................................51

FIGURE 15 : CHARACTERISTICS OF A MOTIVATING JOB.......................................53

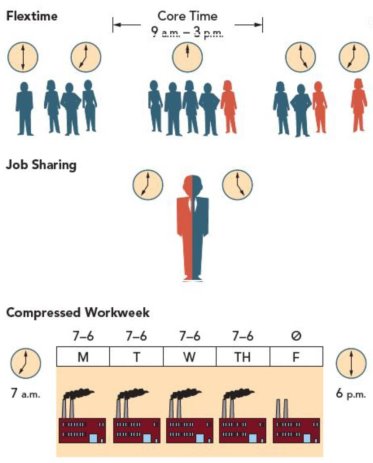

FIGURE 16 : ALTERNATIVE TO 8-TO-5 JOB.......................................................55

FIGURE 17 : STAGES OF INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN......................................59

FIGURE 18 : NEEDS ASSESSMENT................................................................60

FIGURE 19 : OVERVIEW OF USE OF INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS............................65

FIGURE 20 : MEASURES OF TRAINING EVALUATION.....................................72

FIGURE 21 : THE FOUR APPROACHES TO EMPLOYEE DEVELOPMENT.........................75

FIGURE 22 : STEPS IN THE TELUS DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM.....................................78

FIGURE 23 : LEVELS OF GLOBAL PARTICIPATION............................................83

FIGURE 24 : FACTORS AFFECTING HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL MARKETS............85

FIGURE 25 : FIVE DIMENSIONS OF CULTURE................................................87

FIGURE 26 : EMOTIONAL CYCLE ASSOCIATED WITH A FOREIGN ASSIGNMENT................95

FIGURE 27 : EARNINGS IN SELECTED OCCUPATIONS IN SEVEN CITIES...................100

FIGURE 28 : NORMAL ANNUAL HOURS WORKED IN MANUFACTURING....................................103

FIGURE 29 : THE BALANCE SHEET FOR DETERMINING EXPATRIATE COMPENSATION..........105

FIGURE 30 : CUSTOMER-ORIENTED PERSPECTIVE OF HRM.....................................108

TABLE 1 : RESPONSIBILITIES OF HR DEPARTMENT............................16

TABLE 2 : EMPLOYABILITY SKILLS........................................18

TABLE 3 : TRAINING VERSUS DEVELOPMENT.................................57

TABLE 4 : WAYS THAT TRAINING HELPS EMPLOYEES LEARN....................70

TABLE 5 : WHAT KEEPS FOREIGN WORKERS ENGAGED..........................89

TABLE 6 : EFFECTS OF CULTURE ON TRAINING DESIGN.......................97

1. Introduction

What do PricewaterhouseCoopers, Research in Motion and Google Inc. have in common? They have all been recently recognized as excellent employers with progressive human resource management practices. The list of employment awards is growing, raising the bar on what it takes to attract, retain, and engage top talent. As labor markets become increasingly competitive, human resource professionals are being called upon to provide people management practices that not only support the organization's priorities but also provide for competitive success in a global marketplace. Organizations also strive to create an employment brand that resonates with specific employees. Perhaps no organization has received more attention or has a stronger brand than Google. Google is known for its people practices and employee-first culture that directly contribute to its success. The work environment provides "Googlers" unlimited amounts of free, chef-prepared food at all times of the day, lap pools, onsite massages, car washes, oil changes, dry-cleaning, laundry service, and haircuts. Google's "20-percent time" gives employees 20 present of their day to "work on what they're really passionate about"—and tangible organizational outcomes often result. For example, Gmail came about from one Google employee's 20-percent time efforts. Perhaps it is no surprise that Google receives 1300 resumes every day and is able to attract and retain some of the world's top talent.1 Organizations of all sizes and in all industries are increasingly recognizing the importance of people. This is a time of rapid change in the market—a time when Canadian organizations are constantly trying to keep pace and remain competitive. In today's knowledge-based economy, I rely on people to generate, develop, and implement ideas and the human resource function has an important role in ensuring that organizations have the people capacity to execute strategic objectives. 2  Figure 1 : Human Resource ManagementPractices

Figure 1 : Human Resource ManagementPractices

Human resource management (HRM) centres on the policies, practices, and systems that influence employees' behavior, attitudes, and performance. Many companies refer to HRM as "people practices." Figure 1 emphasizes that there are several important HRM practices that contribute to an organization's ability to realize the full benefit of its talent: analysing work and designing jobs, attracting potential employees, choosing employees, preparing employees to perform their jobs and for the future (training and development), supporting their performance (performance management), rewarding employees (compensation), creating a positive work environment (employee and labor relations), and supporting the organization’s strategy. In addition, HRM has responsibility for providing safe work environments and assuring compliance with legal requirements. An organization performs best when all of these practices are managed systematically. At companies with effective HRM, employees and customers tend to be more satisfied, and the companies tend to be more innovative, have greater productivity, and develop a more favourable reputation in the community.3

2. Strategies, Trends, and Challenges in Human Resource Management

Managers and economists traditionally have seen human resource management as a necessary expense, rather than as a source of value to their organizations. Economic value is usually associated with capital, equipment, technology, and facilities. However, in the changing corporate environment, more and more organizations are awakening to the importance of human capital as the next competitive advantage.4

2.1. The Value of People

A barrier to business expansion is not only availability of financial capital but also access to talent that is, human capital. In summary, people are crucial to organizational success and the human and intellectual capital of an organization's workforce provides an opportunity for substantial competitive advantage. As the 'resident people experts,' HR leaders are ideally suited to advise their organization on the best means for realizing their objectives. Decisions such as whom to hire, what to pay, what training to offer, and how to evaluate employee performance directly affect employees' motivation, engagement, and ability to provide goods and services that customers value. Companies that attempt to increase their competitiveness by investing in new technology and promoting quality throughout the organization also invest in state-of-the-art staffing, training, and compensation practices. These types of practices indicate that employees are viewed as valuable investments.5

The concept of "human resource management" implies that employees are re- sources of the employer. As a type of resource, human capital means the organization's employees, described in terms of their training, experience, judgment, intelligence, relationships, and insight the employee characteristics that can add economic value to the organization. In other words, whether it manufactures bicycles or forecasts the weather, for an organization to succeed at what it does, it needs employees with certain qualities, such as particular kinds of skills and experience. This view means employees in today's organizations are not interchangeable, easily replaced parts of a system but the source of the company's success or failure. By influencing who works for the organization and how those people work, human resource management therefore contributes to such basic measures of an organization's success as quality, profitability, and customer satisfaction. Figure 2 shows this relationship.  Figure 2 : Impact of Human ResourceManagement

Figure 2 : Impact of Human ResourceManagement

Human resource management is critical to the success of organizations, because human capital has certain dualities that make it valuable. In terms of business strategy, an organization can succeed if it has a sustainable competitive advantage (is better than competitors at something, and can hold that advantage over a sustained period of time). Therefore, I can conclude that organizations need the kind of resources that will give them such an advantage. Human Resources have these necessary qualities:

- Human resources are valuable. High-quality employees provide a needed service as they perform many critical functions.

- Human resources are rare in the sense that a person with high levels of the needed skills and knowledge is not common. An organization might spend months looking for a talented and experienced manager or technician.

- Human resources cannot be imitated. To imitate human resources at a high- performing competitor, you would have to figure out which employees are providing the advantage and how. Then you would have to recruit people who can do precisely the same thing and set up the systems that enable those people to imitate your competitor.

- Human resources have no good substitutes. When people are well trained and highly motivated, they learn, develop their abilities, and care about customers. It is difficult to imagine another resource that can match committed and talented employees.

These qualities imply that human resources have enormous potential. An organization realizes this potential through its approach to human capital management, that is, how it practises human resource management. Effective management of human resources can form the foundation of a high- performance work system and organization in which technology, organizational structure, people, and processes all work together to give an organization an advantage in the competitive environment. As technology changes how organizations manufacture, transport, communicate, and keep track of information, human resource management must ensure that the organization has the right kinds of people to meet the new challenges. Maintaining a high- performance work system might include development of training programs, recruitment of people with new skill sets, and establishment of rewards for such behaviors as teamwork, flexibility, and learning.

2.2. Responsibilities of Human Resource Departments

In all but the smallest organizations, a human resource department is responsible for the functions of human resource management. On average, an organization has one HR staff person for every 100 employees served by the department; however, this ratio may vary widely across organizations. Another general guideline is that a specialized HR role is often created when an organization has reached the size of approximately 40 employees. Table 1 details the responsibilities of human resource departments. These responsibilities include the practices introduced in Figure 1 plus two areas of responsibility that support those practices: (1) establishing and administering human resource policies and (2) ensuring compliance with legal requirements. Although the human resource department has responsibility for these areas, many of the requirements are performed by supervisors or others inside or outside the organization. No two human resource departments have precisely the same roles, because of differences in organization sizes and characteristics of the workforce, the industry, and management's values. In some companies, the HR department handles all the activities listed in Table 1. In others, it may share the roles and duties with managers and supervisors of other departments such as finance, operations, or information technology. When managers and supervisors actively perform a variety of HR activities, the HR department usually retains responsibility for consistency and compliance with all legal requirements. In some companies, the HR department actively advises top management. In others, the department responds to top-level management decisions and implements staffing, training, and compensation activities in light of company strategy and policies.

|

|

| Analysis and design of work | Work analysis; job design; job descriptions |

| Recruitment and selection | Identify needs; recruiting; interviewing and screening; deployment of staff; and outplacement |

| Training and development | Orientation; learning strategies; design, deliver, and evaluate programs; career development |

| Performance management | Integrate performance measures; performance appraisal systems; assist and coach supervisors |

| Compensation and rewards | Develop and administer compensation and incentive programs; benefit program design and implementation; pension plans; payroll |

| Employee and labour relations | Employee and labor relations; Terms and conditions of employment, communication; employee involvement; labor relations |

| Strategy | Strategic partner in organizational effectiveness; change and development; workforce planning |

| Human resource policies | Guide and implement policy; create and manage systems to collect and safeguard HR information |

| Compliance with legislation | Implement policies to ensure compliance with all legal requirements; reporting requirements |

Table 1 : Responsibilities of HR Department 6

Let's take a look at an overview of the HR functions and some of the options available for carrying them out. Human resource management involves both the selection of which options to use and the activities related to implementation.

Analyzing and Designing Jobs

To produce their given product or service (or set of products or services), companies require that a number of tasks be performed. The tasks are grouped in various combinations to form jobs. Ideally, the tasks should be grouped in ways that help the organization to operate efficiently and to obtain people with the right qualifications to do the jobs well. This function involves the activities of job analysis and job design. Job analysis is the process of getting detailed information about jobs. Job design is the process of defining the way work will be performed and the tasks that a given job requires.

Recruiting and Hiring Employees

On the basis of job analysis and job design, an organization can determine the kinds of employees it needs. With this knowledge, it carries out the function of recruiting and hiring employees. Recruitment is the process through which the organization seeks applicants for potential employment. Selection refers to the process by which the organization attempts to identify applicants with the necessary knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics that will help the organization achieve its goals. An organization makes selection decisions in order to add employees to its workforce, as well as to transfer existing employees to new positions.

At some organizations, the selection process may focus on specific skills, such as experience with a particular programming language or type of equipment. At others, selection may focus on general abilities, such as the ability to work as part of a team or find creative solutions. The focus an organization favors will affect many choices, from the way the organization measures ability, to the questions it asks in interviews, to the places it recruits. Table 2 lists employability skills, attitudes, and behaviors needed to participate and progress in today's dynamic

world of work. HR professionals also provide guidance related to redeploying employees, termination, and outplacement.

|

|

|

| Communicate | Demonstrate positive attitudes and behaviors | Work with others |

| Manage information | Be responsible | Participate in projects and tasks |

| Use numbers | Be adaptive | |

| Think and solve problems | Learn continuously Work safely |

Table 2 : EmployabilitySkills7

Training and Developing Employees

Although organizations base hiring decisions on candidates' existing qualifications, most organizations provide ways for their employees to broaden or deepen their knowledge, skills, and abilities. To do this, organizations provide for employee training and development. Training is a planned effort to enable employees to learn job-related knowledge, skills, and behavior. For example, many organizations offer safety training to teach employees safe work habits. Development involves acquiring knowledge, skills, and behavior that improve employees' ability to meet the challenges of a variety of new or existing jobs, including the client and customer demands of those jobs. Development programs often focus on preparing employees for management responsibility.

Managing Performance

Managing human resources includes keeping track of how well employees are performing relative to objectives such as job descriptions and goals for a particular position. The process of ensuring that employees' activities and outputs match the organization's goals is called performance management. The activities of performance management include specifying the tasks and outcomes of a job that contribute to the organization's success. Then various measures are used to compare the employee's performance over some time period with the desired performance. Often, rewards the topic of the next section are developed to encourage good performance.

Compensation and Rewards

Planning pay and benefits involves many decisions often complex and based on knowledge of a multitude of legal requirements. An important decision is how much to offer in salary or wages, as opposed to bonuses, commissions, and other performance-related pay. Other decisions involve which benefits to offer, from retirement plans to various kinds of insurance to other more intangible rewards such as opportunities for learning and personal growth. All such decisions have implications for the organization's bottom line, as well as for employee motivation. Administering pay and benefits is another big responsibility. Organizations need systems for keeping track of each employee's earnings and benefits. Employees need information about their health plan, retirement plan, and other benefits. Keeping track of this involves extensive record keeping and reporting to management, employees, and others, while ensuring compliance with all applicable legislation.

Maintaining Positive Employee and Labor Relations

Organizations often depend on human resource professionals to help them identify and perform many of the tasks related to maintaining positive relations with employees. This function often includes providing for communications to employees. In organizations where employees belong to a union, labor relations entails additional responsibilities. The organization periodically conducts collective bargaining to negotiate an employment contract with union members. The HR department also maintains communication with union representatives to ensure that issues are resolved as they arise.

Establishing and Administering Human Resource Policies

All the human resource activities described so far require fair and consistent decisions, and most require substantial record keeping. Organizations depend on their HR department to help establish policies related to hiring, discipline, promotions, benefits, and the other activities of human resource management. All aspects of human resource management require HR professionals to collect and safeguard information. From the preparation of employee handbooks, to processing job applications, performance appraisals, benefits enrolment, and government-mandated reports, handling records about employees requires accuracy as well as sensitivity to employee privacy.

Ensuring Compliance with Legislation

The government has many laws and regulations concerning the treatment of employees. These laws govern such matters as human rights, employment equity, employee safety and health, employee compensation and benefits, and employee privacy. Most managers depend on human resource professionals to help them keep up to date and on track with these requirements. Ensuring compliance with laws requires that human resource professionals keep watch over a rapidly changing legal landscape.

2.3. Focus on Strategy

Traditional management thinking treated human resource management primarily as an administrative function, but managers are increasingly seeing a more central role for HRM. They are looking at HRM as a means to support a company's strategy its plan for meeting broad goals such as profitability, quality, and market share. 8This strategic role for HRM has evolved gradually. At many organizations, managers still treat HR professionals primarily as experts in designing and delivering HR systems. But at a growing number of organizations, HR professionals are strategic partners with other managers.9 This means they use their knowledge of the business and of human resources to help the organization develop strategies and to align HRM policies and practices with those strategies. In a recent study of almost 200 European organizations surveyed by Deloitte Consulting, 41 percent of human resource leaders describe their departments as strategic partners while 31 percent still view themselves as administrative champions. Part of the problem for HR professionals is that employees are concerned about getting help with traditional human resource administrative responsibilities such as completing benefit forms while executives want senior HR leaders to be partners in strategic planning.10 The specific ways human resource professionals support the organization's strategy vary according to their level of involvement and the nature of the strategy. Strategic issues include emphasis on productivity improvement; attracting, engaging, and retaining talent; international expansion and outsourcing decisions. Another important element of this responsibility is workforce planning, identifying the numbers and types of employees the organization will require in order to meet its objectives. Using these estimates, the human resource department helps the organization forecast its needs for hiring, training, and reassigning employees. Planning also may show that the organization will need fewer employees to meet anticipated needs. In that situation, human resource planning includes how to handle or avoid layoffs.

Often, an organization's strategy requires some type of change for example, adding, moving or closing facilities, applying new technology, or entering markets in other regions or countries. Common reactions to change include fear, anger, and confusion. The organization may turn to its human resource department for help in managing the change process. Skilled human resource professionals can apply knowledge of human behavior, along with performance management tools, to help the organization manage change constructively.

Productivity Improvement

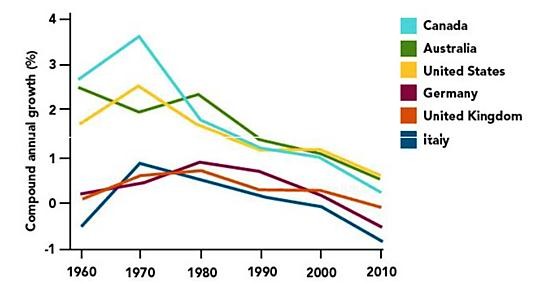

To compete in today's global economy, companies need to enhance productivity. The relationship between an organization's outputs (products, information, or services) and its inputs (e.g., people, facilities, equipment, data, and materials) is referred to as productivity. Europe's labor force productivity growth is forecast to average 1.5 percent per year between 2003 and 2015 in contrast with 1.7 percent per year in the United States. This productivity gap between Europe and the United States threatens Europe's ability to compete globally. As illustrated in Figure 3, Europe is also a productivity laggard from a global perspective, significantly underperforming not only the United States but many other nations as well.11

Expanding into Global Markets

Companies are finding that to survive and prosper they must compete in international markets as well as fend off foreign competitors' attempts to gain ground in Europe. To meet these challenges, European businesses must develop global markets, keep up with competition from overseas, hire from an international labor pool, and prepare employees for global assignments.

Figure 3 : Average Label Productivity Growth(%)12

Figure 3 : Average Label Productivity Growth(%)12

Study of companies that are successful and widely admired suggests that these companies not only operate on a multinational scale, but also have workforces and corporate cultures that reflect their global markets.13 These companies, which include Research in Motion, Scotia bank, General Electric, Microsoft, RBC, and Intel, focus on customer satisfaction and innovation. In addition, they operate on the belief that people are the company's most important asset. Placing this value on employees requires the companies to emphasize human resource practices, including rewards for superior performance, measures of employee satisfaction, careful selection of employees, promotion from within, and investment in employee development.

2.4. The Global Workforce

For today's and tomorrow's employers, talent comes from a global workforce. Organizations with international operations hire at least some of their employees in the foreign countries where they operate. And even small businesses that stick close to home hire qualified candidates who are immigrants. For an organization to operate in other countries, its HR practices must take into consideration differences in culture and business practices. Consider how Starbucks Coffee handled its expansion into Beijing, China.14 Demand for qualified managers in Beijing exceeds the local supply, so Starbucks researched the motivation and needs of potential managers. The company learned that in traditional Chinese-owned companies, rules and regulations allowed little creativity and self-direction. Starbucks distinguished itself as an employer by emphasizing its casual culture and opportunities for career development. The company also spends considerable time training employees. Even hiring at home may involve selection of employees from other countries. The 21st century, like the beginning of the last century, has been years of significant immigration. Foreign-born people account for virtually one in five of Europe's total population the highest level in 75 years. The impact of immigration is especially significant in some regions of Europe.

International Assignments

Besides hiring an international workforce, organizations must he prepared to send employees to other countries. This requires HR expertise in selecting employees for international assignments and preparing them for those assignments. Employees who take assignments in other countries are called expatriates. European companies must prepare employees to work in other countries. Companies must carefully select employees to work abroad on the basis of their ability to understand and respect the cultural and business norms of the host country. Qualified candidates also need language skills and technical ability.

Outsourcing

Many organizations are increasingly outsourcing and offshoring business activities. Outsourcing refers to the practice of having another company (a vendor, third-party provider, or consultant) provide services. For instance, a manufacturing company might outsource in accounting and transportation to business that specialize in these activities. Outsourcing gives the company access to in-depth expertise and is often more economical as well. In addition to manufacturing, software development and call center operations are other functions typically considered for out-sourcing. Offshoring, on the other hand, refers to setting up a business enterprise in another country, for example, setting up a factory in China to manufacture products at less cost than in Canada. Increasingly, organizations are offshore outsourcing, that is, the company providing outsourced services is located in another country rather than the organization's home country. For example, The Portables, trade-show display and exhibits maker based in Richmond, B.C., have increased annual sales dramatically since starting its use of offshore outsourcing. Hanif Mulijinai, president of The Portables, says offshore outsourcing was never the plan for his company. "But I find with some of the newer products, it's a lot easier to get some of the products manufactured in China. It's a lot quicker and less expensive," he says. "Some of the quality of the work they do is very scary, it's so good."15 Overall there are two primary categories of outsourcing and offshoring implications to Europe:

- European companies are likely to increase their use of outsourcing and offshoring. To cut costs and reduce capital investment. Most likely their use of outsourcing and offshoring to the ever-growing list of countries such as India, China and Mexico that are actively seeking economic diversification and investment.

- Europe is losing its attractiveness as an outsourcing destination. It has slipped from second to eighth place as an attractive outsourcing destination behind India, China, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, and Brazil in a study conducted by A. T. Kearney.

Mergers and Acquisitions

Increasingly, organizations are joining forces through mergers (two companies becoming one) and acquisitions (one company buying another). These deals do not always meet expectations, and often failures may be due to "people issues." Recognizing this, some companies now heavily weigh the other organization's culture before they embark on a merger or acquisition. HRM should have a significant role in carrying out a merger or acquisition. Differences between the businesses involved in the deal make conflict inevitable. Training efforts should therefore include development of skills in conflict resolution. Also, HR professionals have to sort out differences in the two companies' practices with regard to rewards, performance appraisal, and other HR systems. Settling on a consistent structure to meet the combined organization's goals may help to bring employees together. HR's role is in engaging top talent and keeping them on board with challenging opportunities following a merger or acquisition.

- Required Professional Capabilities (RPCs) and Certification of HR Professionals

The knowledge, skills, abilities, and other attributes required by an individual working in HR to demonstrate professional competence has been researched and defined by the European Council of Human Resources Associations. The resulting Required Professional Capabilities are grouped into seven functional dimensions as shown in Figure 4.  Figure 4 : Required Professional Capabilities by Functional Dimensions

Figure 4 : Required Professional Capabilities by Functional Dimensions

2.6. Ethics in Human Resource Management

Whenever people's actions affect one another, ethical issues arise, and business decisions are no exception. Ethics refers to the fundamental principles of right and wrong; ethical behavior is behavior that is consistent with those principles. Business decisions, including HRM decisions, should be ethical, but the evidence suggests that is not always what happens. Recent surveys indicate that the general public and managers do not have positive perceptions of the ethical conduct of businesses. For example, in a survey conducted by the Wall Street Journal, 4 out of 10 executives reported they had been asked to behave unethically.16 The HR How-To box provides the Code of Ethics that identifies standards for professional and ethical conduct of HR practitioners. For human resource practices to be considered ethical they must satisfy the three basic standards summarized in Figure 5 First, HRM practices must result in the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Second, human resource practices must respect legal requirements including human rights and privacy. Third, managers must treat employees and customers equitably and fairly. To explore how ethical principles apply to a variety of decisions.  Figure 5 : Standards for Identifying Ethical Practices17

Figure 5 : Standards for Identifying Ethical Practices17

Closely related to the discussion of ethics and ethical practices is HR's role in organizational values and corporate social responsibility. For example, "there is increasing evidence that interest in environmental issues is motivating people's behavior as consumers, employees and jobseekers."18

Code of Ethics

Competence. Maintain competence in carrying out professional responsibilities and provide services in an honest and diligent manner. Ensure that activities engaged in are within the limits of one's knowledge, experience, and skill. When providing services outside one's level of competence, or the profession, the necessary assistance must be sought so as not to compromise professional responsibility.

Legal requirements. Adhere to any statutory acts, regulation, or by-laws which relate to the field of human resources management, as well as all civil and criminal laws, regulations, and statutes that apply in one's jurisdiction. Not knowingly or otherwise engage in or condone any activity or attempt to circumvent the clear intention of the law.

Dignity in the workplace. Support, promote and apply the principles of human rights, equity, dignity and respect in the workplace, within the profession, and in society as a whole.

Balancing interests. Strive to balance organizational and employee needs and interests in the practice of the profession.

Confidentiality. Hold in strict confidence all confidential information acquired in the course of the performance of one's duties, and not divulge confidential information unless required by law and/or where serious harm is imminent.

Conflict of interest. Either avoid or disclose a potential conflict of interest that might influence or might be perceived to influence personal actions or judgments. Professional growth and support of other professionals. Maintain personal and professional growth in human resources management by engaging in activities that enhance the credibility and value of the profession. SOURCE: © Reproduced with permission by the Canadian Council ofHuman Resources Associations, www. cchra.ca/Web/ethics/content.aspx?f = 2956,retrievedMarch 12,2008.

2.7. HR Responsibilities of Supervisors and Line Managers

Although many organizations have human resource departments, HR activities are by no means limited to the specialists who staff those departments. In large organizations, HR departments advise and support the activities of the other departments. In small organizations, there may be an HR specialist, but many HR activities are carried out by supervisors and other line managers. Either way, non- HR managers need to be familiar with the basics of HRM and their role with regard to managing human resources. Supervisors and non-HR managers typically have responsibilities related to all the HR functions. Figure 6 shows some HR responsibilities that supervisors and line managers are likely to be involved in. Organizations depend on supervisors to help them determine what kinds of work need to be done (job analysis and design) and in what quantities (workforce planning). Supervisors and line managers typically interview job candidates and participate in the decisions about which candidates to hire. Many organizations expect supervisors to train employees in some or all aspects of the employees' jobs. Supervisors conduct performance appraisals and may recommend pay increases. And, of course, supervisors and line managers play a key role in employee relations, because they are most often the voice of management for their employees, representing the company on a day-to-day basis. Throughout these activities, supervisors and line managers can participate in HRM by taking into consideration how decisions and policies will affect their employees. Understanding the principles of communication, motivation, and other elements of human behavior can help supervisors and line managers engage and inspire the best from the organization's human resources.  Figure 6 : Typical Areas ofInvolvements

Figure 6 : Typical Areas ofInvolvements

2.8. Careers in Human Resource Management

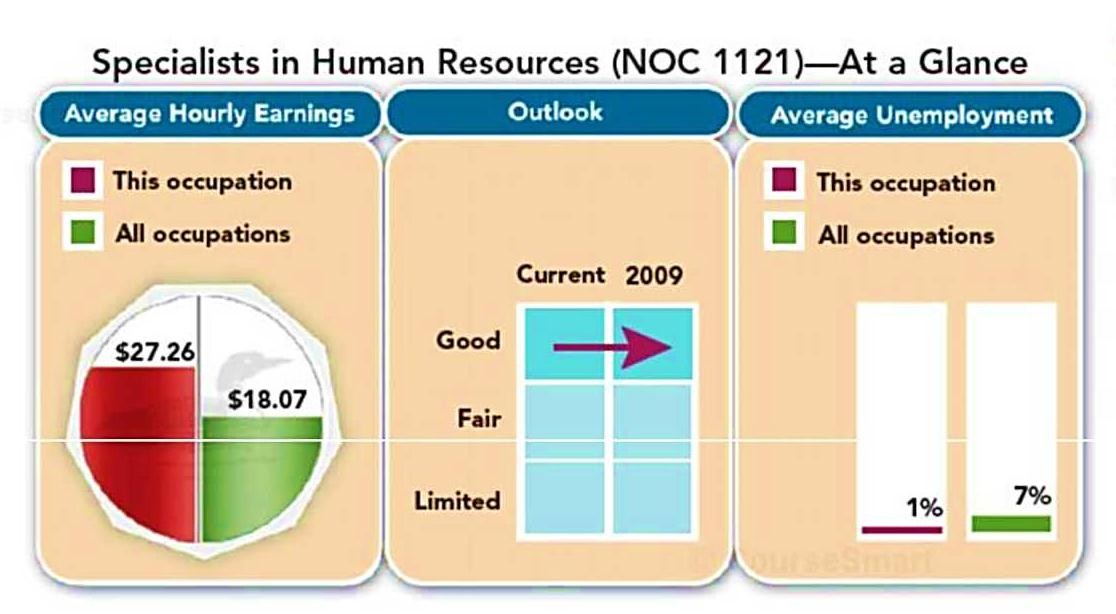

There are many different types of jobs in the HRM profession. Figure 7 shows selected HRM positions and their salaries. The salaries vary according to education and experience, as well as the type of industry in which the person works. The Occupational Classification identifies one specific broad classification of human resources occupations: "Specialists in Human Resources." Figure 8 provides a summary of average hourly earnings, employment outlook, and average levels of unemployment. This resource also provides similar information for thousands of other occupations. Some positions in HRM involve work in specialized areas such as recruiting, training, or labor and industrial relations. Other positions call for generalists to perform a full range of HRM activities, including recruiting, training, compensation, and employee relations. Many recent entrants have a university degree or college diploma. In 2011, CHRP candidates will require a degree to qualify for the CHRP designation, a change likely to advance the status of the CHRP among employers.  Figure 7 : Salaries for HRM Positions

Figure 7 : Salaries for HRM Positions  Figure 8 : Average Hourly Earnings in HR

Figure 8 : Average Hourly Earnings in HR

SOURCE: Based on Society for Human Resource Management—Mercer Survey 2003,as reported in J. Vocino, "On the Rise," HR Magazine, November 2003, pp. 75-84; and F.Hansen, "2003 Data Bank Annual," Workforce Management 82, no. 13 (2003), p. 88. Based onSocietyfor Human Resource Management—2003 as reported in J. Vocino, "On the Rise," HR Magazine, pp. 75-84; and F. Hansen, "2003 Data Bank Annual," Vvorkioros Management82, no. 13 (2003), p.88.

A well-rounded educational background will likely serve a person well. As one HR professional noted, one of the biggest misconceptions is that [HRM] is all warm and fuzzy communications with the workers. Or that it is creative and involved in making a more congenial atmosphere for people at work. Actually it is both of those some of the time, but most of the time it is a big mountain of paperwork, which calls on a myriad of skills besides the "people" type. It is law, accounting, philosophy, and logic as well as psychology, spirituality, tolerance, and humility.

2.9. Change in the Labor Force

The labor force is a general way to refer to all the people willing and able to work. For an organization, the internal labor force consists of the organization's workers—its employees and the people who work at the organization. This internal labor force is drawn from the organization's external labor market, that is, individuals who are actively seeking employment. The number and kinds of people in the external labor market determine the kinds of human resources available to an organization (and their cost). Human resource professionals need to be aware of trends in the composition of the external labor market, because these trends affect the organization's options for creating a well-skilled, motivated internal labor force. One significant trend relates to the impending shortage of workers as the labor force actually shrinks in some developed countries. Generation X (born 1965-1980) grew up in the wake of the baby boomers. Dual- income families produced a generation of children with greater responsibility for taking care of themselves. Generation X employees are inclined to be cynical about the future because of their experience with recessions and downsizing and tend to be independent, technology-sawy, and results-driven. Generation Y (born 1981- 2000) have been born and raised in a multicultural society resulting in tolerance to differences in race, religion, and culture.19

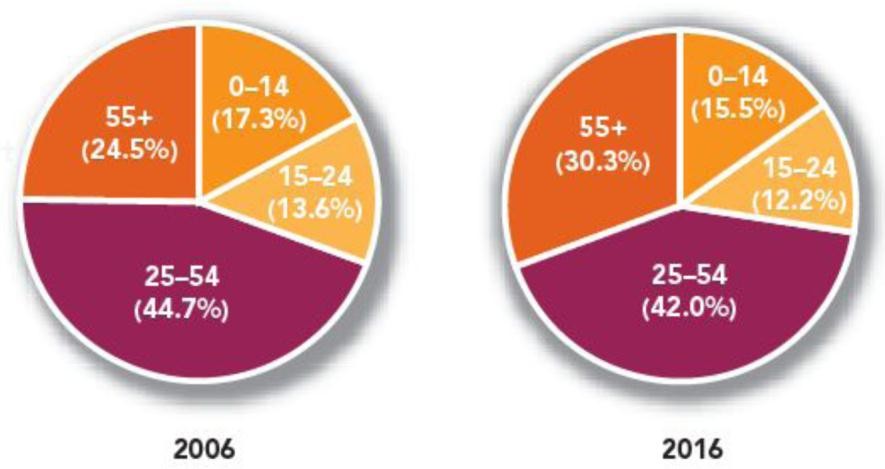

Figure 9 : Decline of LabourForce

Figure 9 : Decline of LabourForce  Figure 10 : Age Distribution Projection of the EuropeanPopulation20

Figure 10 : Age Distribution Projection of the EuropeanPopulation20

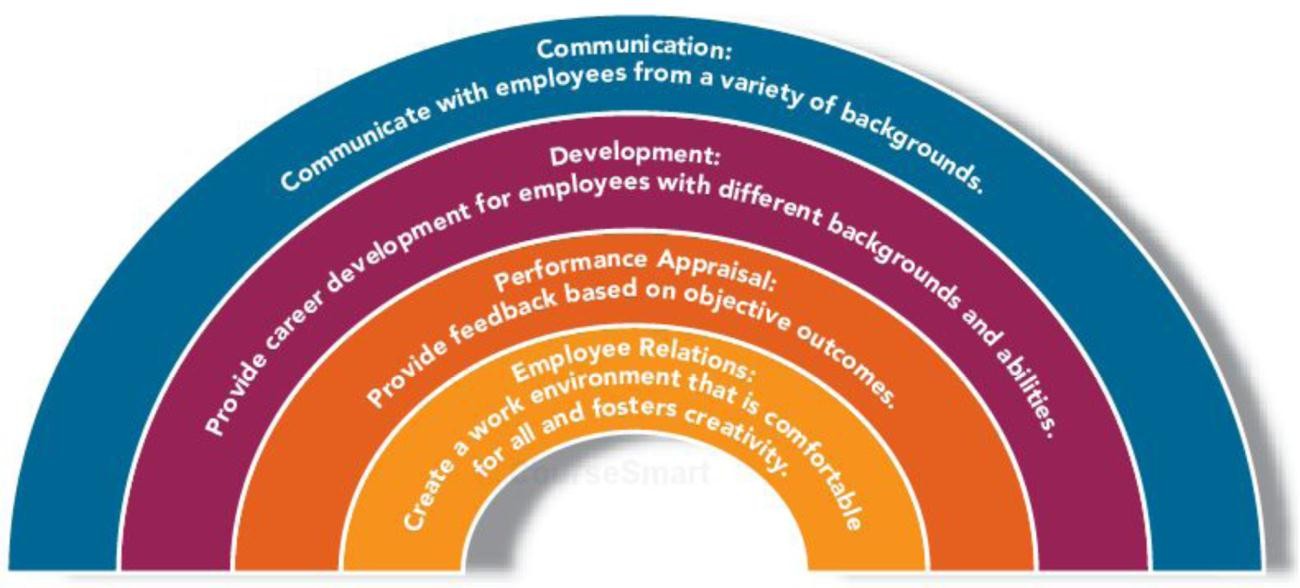

* Due to rounding, the totals do not always add up to the sum of thefigure Employees view work as a means to self-fulfillment that is, a means to more fully use their skills and abilities, meet their interests, and live a desirable lifestyle. One report indicates that if employees receive opportunities to fully use and develop their skills, has greater job responsibilities, believe the promotion system is fair, and have a trustworthy manager who represents die employee’s best interests; they are more committed to their companies.21 Fostering these values requires organizations to develop HRM practices that provide more opportunity for individual contribution and entrepreneurship (in this context, taking responsibility for starting up something new).22 Because many employees place more value on the quality of network activities and family life than on pay and production, employees will demand more flexible work policies that allow them to choose work hours and the places where work is performed.  Figure 11 : HRM Practices that Support DiversityManagement23

Figure 11 : HRM Practices that Support DiversityManagement23

Employers will likely find that many talented older workers want to continue contributing through their work, though not necessarily in a traditional eight-to- five job. For organizations to attract and keep talented older workers, many will have to rethink how they design jobs. Phyllis Ostrowsky, in her mid-fifties, enjoyed her position as a store manager for 13 years, and she went out of her way to provide good customer service. But her job responsibilities and hours expanded to the point they became excessive. She eventually was working 12-hour days and was too busy to give customers the personal touch she liked to deliver. Ostrowsky therefore left her store job for a position as an office manager with another company.24

2.10. Change in the Employment Relationship

Economic downturns resulting in layoffs and bankruptcies have played a major role in changing the basic relationship between employers and employees.

A New Psychological Contract

I can think of the relationship between employers and employees in terms of a psychological contract, a description of what an employee expects to contribute in an employment relationship and what the employer will provide the employee in exchange for those contributions.25 Unlike a sales contract, the psychological contract is not formally put into writing. Instead, it describes unspoken expectations that are widely held by employers and employees. In the traditional version of this psychological contract, organizations expected their employees to contribute time, effort, skills, abilities, and loyalty. In return, the organizations would provide job security and opportunities for promotion. However, this arrangement is being replaced with a new type of psychological contract. To stay competitive, modern organizations must frequently change the quality, innovation, creativeness, and timeliness of employee contributions and the skills needed to make those contributions. This need has led to organizational restructuring, mergers and acquisitions, layoffs, and longer hours for many employees. Companies demand excellent customer service and high productivity levels. They expect employees to take more responsibility for their own careers, from seeking training to balancing work and family. These expectations result in less job security for employees, who can count on working for several companies over the course of a career. Today, the average length of time a person holds a job is seven years.26 In exchange for top performance and working longer hours without job security, employees want companies to provide flexible work schedules, effective work. For Many, Taking Work Home Is Often a Job Without Reward. The Watt Street Journal. Interactive Edition, 2002, March 5., p 48 environments, more control over how they accomplish work, training and development opportunities, and financial incentives based on how the organization performs.

Flexibility

The new psychological contract largely results from the HRM challenge of building a committed, productive workforce in turbulent economic conditions that offer opportunity for financial success but can also quickly turn sour, making every employee expendable. From the organization's perspective the key to survival in a fast-changing environment is flexibility. Organizations want to be able to change as fast as customer needs and economic conditions change. Flexibility in human resource management includes flexible staffing levels and flexible work schedules. A flexible workforce is one the organization can quickly reshape and resize to meet its changing needs. To be able to do this without massive hiring and firing campaigns, organizations are using more flexible staffing arrangements. Flexible staffing arrangements are methods of staffing other than the traditional hiring of full-time employees. There are a variety of methods, the following being most common:

- Independent contractors are self-employed individuals with multiple clients.

- On ‘Call workers are persons who work for an organization only when they are needed.

- Temporary workers are employed by a temporary agency; client organizations pay the agency for the services of these workers

- Contract company workers are employed directly by a company for a specific time specified in a written contract.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL COMPANIES

Research in Motion (RIM) is a leading designer, manufacturer, and marketer of innovative wireless solutions for the worldwide mobile communications market. RIM's portfolio of award-winning products, including the BlackBerry, is used by organizations and individuals around the world. The company, founded in 1984 and based in Waterloo, Ontario, continues to grow rapidly and is a significant player in the global market. RIM's core Asia Pacific contact center is in Singapore, but is expanding with a presence in Hong Kong, China, Australia, and India. RIM's European headquarters are based in London and current expansion includes France, Germany, Poland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Hungary, Italy, Spain, and South Africa. Operations in the Americas include several offices in the United States, including ones in Chicago, Dallas, and Seattle, and in Mexico and the Caribbean. A search of the "Careers" area of RIM's website provides some insight about the extent of globalization of RIM's business structure and operations. For example, at the time of this writing, 1,043 job openings were listed for RIM's worldwide operations. This included openings for Manager of Compensation 6k Benefits in the UK, Business Development Manager in Hong Kong, Field Marketing and Training Specialist in Mexico, Facilities Manager in Fort Lauderdale, and a Public Relations Manager based in Sydney, Australia. According to a PwC survey of almost 3,000 line executives and HR executives from 12 countries, international competition is the number one factor affecting human resource management. The globalization of business structures and globalization of the economy ranked fourth and fifth, respectively. Business decisions such as whether to enter foreign markets or set up operations in other countries are complex, and in the course of moving and executing them many human resource issues surface.27

This chapter discusses the HR issues that organizations must address in a world of global competition. I begin by describing how the global nature of business is affecting human resource management in modem organizations. Next, I identify how global differences among countries affect the organization's decisions about human resources. Based on personal interview and internal global HR audit provided by PwC I have identified four critical areas of HRM success in this company:

- Preparing for and Acquiring Human Resources

- Managing Talent

- Managing Human Resources Globally

- Creating and Maintaining High-Performance Organizations28

In the following sections I will explore those in international settings and will examine guidelines for managing employees on international assignments.

3. Preparing for and Acquiring Human Resources

Speaking specifically about recruitment, number one, in order to properly assess candidates and recognize talent, you need to have a genuine interest in others. Talent is not always obvious, so be engaged, learn their story! The second thing you need is to develop good questioning techniques that put people at ease. People are more likely to respond in a straightforward manner when the interviewer is on their side. Give candidates the opportunity to think and express themselves. You will be much more likely to extract valid, accurate, and pertinent data about the interviewee. The third essential attribute is you have to be kind and empathetic. Searching for a job is often not a pleasurable experience. Job seekers deal with the inevitable rejection and worries associated with their future and financial security, and often question their self-worth. Whether or not they are successful in obtaining a position through you, they should remember speaking with you and dealing with your company as a positive experience. Finally, act with urgency.

Work Flow in Organizations

Informed decisions about jobs take place in the context of the organization's overall work flow. Through the process of work flow design, managers analyze the tasks needed to produce a product or service. With this information, they assign these tasks to specific jobs and positions. (A job is a set of related duties. A position is the set of duties performed by one person. A school has many teaching positions; the person filling each of those positions is performing the job of teacher.) Basing these decisions on workflow design can lead to better results than the more traditional practice of looking at jobs individually.

Work Flow Analysis

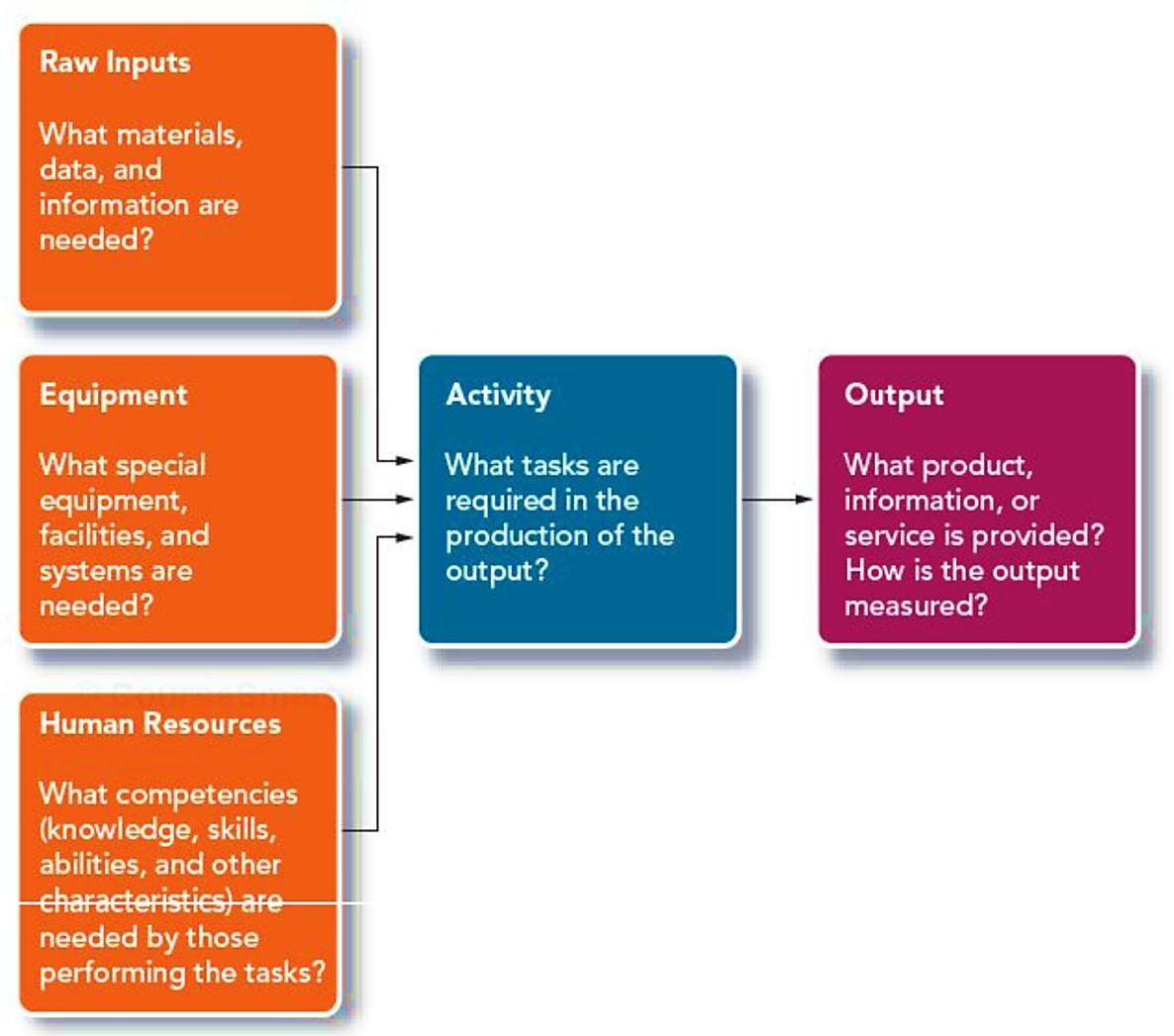

Before designing its workflow, the organization's planners need to analyze what work needs to be done. Figure 12 shows the elements of a workflow analysis. For each type of work, such as producing a product line or providing a support service (accounting, legal support, and so on), the analysis identifies the output of the process, the activities involved, and three categories of inputs: raw inputs (materials and intonation), equipment, and human resources. Outputs are the products of any work unit, whether a department, team, or individual. An output can be as readily identifiable as a completed purchase order, and considers not only the amount of output but also quality standards. This attention to outputs has only recently gained attention among HR professionals. However, it gives a clearer view of how to increase the effectiveness of each work unit.  Figure 12 : Deploying a Work-Unit ActivityAnalysis29

Figure 12 : Deploying a Work-Unit ActivityAnalysis29

For the outputs identified, workflow analysis then examines the work processes used to generate those outputs. Work processes are the activities that members of a work unit engage in to produce a given output. Every process consists of operating procedures that specify how things should be done at each stage of developing the output. These procedures include all the tasks that must be performed in producing the output usually; the analysis breaks down the tasks into those performed by each person in the work unit. This analysis helps with design of efficient work systems by clarifying which tasks are necessary. Typically, when a unit's workload increases, the unit adds people, and when the work load decreases, some members of the unit may busy themselves with unrelated tasks in an effort to appear busy. Without knowledge of work processes, it is more difficult to identify whether the work unit is properly staffed. Knowledge of work processes also can guide staffing changes when work is automated or outsourced at Unifi analysts at the company's headquarters. Unifi no longer requires supervisors to carry out the tasks of monitoring and reporting on production.30

The final stage in workflow analysis is to identify the inputs used in the development of the work unit's product. As shown in Figure 14, these inputs can be broken down into the raw inputs (materials and knowledge), equipment, and human skills needed to perform the tasks. Makers of athletic shoes need nylon and leather, shoemaking machinery, and workers to operate the machinery, among other inputs. Nike and Reebok minimize the cost of inputs by subcontracting manufacturing to factories in countries where wages are low. In contrast, New Balance Athletic Shoes operates a factory in the United States, where modern technology and worker training enable the company to afford North American workers. Teams of employees use automated equipment that operates over 20 sewing machines simultaneously. The employees are cross-trained in all tasks. The highly efficient factory produces shoes much faster than a typical shoe factory in China.31

Work Flow Design and Organization's Structure

Besides looking at the work flow of each process, it is important to see how the work fits within the context of the organization's structure. Within an organization, units and individuals must cooperate to create outputs. Ideally, the organization's structure brings together the people who must collaborate in order to efficiently produce the desired outputs. The structure may do this in a way that is highly centralized (i.e., with authority concentrated in a few people at the top of the organization) or decentralized (with authority spread among many people). The organization may group jobs according to functions (e.g., welding, painting, packaging), or it may set up divisions to focus on products or customer groups. Although there are an infinite number of ways to combine the elements of an organization's structure, I can make some general observations about structure and work design. If the structure is strongly based on function, workers tend to have low authority and to work alone at highly specialized jobs. Jobs that involve teamwork or broad responsibility tend to require a structure based on divisions other than functions. When the goal is to engage employees, companies therefore need to set up structures and jobs that enable broad responsibility, such as jobs that involve employees in serving a particular group of customers or producing a particular product, rather than performing a narrowly defined function. Work design often emphasizes the analysis and design of jobs. Although all of these approaches can succeed, each focuses on one isolated job at a time. These approaches do not necessarily consider how that single job fits into the overall work flow or structure of the organization. To use these techniques effectively, human resource professionals should also understand their organization as a whole. Without this big-picture appreciation, they might redesign a job in a way that makes sense for the job but is out of line with the organization's workflow, structure, or strategy.

3.1. Job Analysis

To achieve high-quality performance, organizations have to understand and match job requirements and people. This understanding requires job analysis, the process of getting detailed information about jobs. Analyzing jobs and understanding what is required to carry out a job provide essential knowledge for staffing, training, performance appraisal, and many other HR activities. For instance, a supervisor's evaluation of an employee's work should be based on performance relative to job requirements. In very small organizations, line managers may perform a job analysis, but usually the work is done by a human resource professional. A large company may have a compensation management or total rewards function that includes job analysts. Organizations may also contract with firms that provide this service.

Job Descriptions

A key outcome of job analysis is the creation of job descriptions. A job description is a list of the tasks, duties, and responsibilities (TDRs) that a job entails. TDRs are observable actions. For example, a news photographer's job requires the jobholder to use a camera to take photographs. If you were to observe someone in that position for a day, you would almost certainly see some pictures being taken. When a manager attempts to evaluate job performance; it is most important to have detailed information about the work performed in the job (i.e., the TDRs). This information makes it possible to determine how well an individual is meeting each job requirement.

Writing a Job Description

Preparing a job description begins with gathering information from sources who can identify the details of performing a task. These sources may include persons already performing the job and, the supervisor, team leader, or, if the job is new, managers who are creating the new position. Asking the purpose of the new position can provide insight into what the company expects this person to accomplish. Besides people, sources of information may include the company's human resource files, such as past job advertisements and job descriptions, as well as general sources of information about similar jobs, such as Human Resources and Social Development system. There are several ways to gather information about the duties of a job:

- Employees can fill out a questionnaire that asks about what they do or complete a diary that details their activities over several days.

- A job analyst can visit the workplace and watch or videotape an employee performing the job. This method is most appropriate for jobs that are repetitive and involve physical activity.

- A job analyst can visit the workplace and ask an employee to show what the job entails. This method is most appropriate for clerical and technical jobs.

- A manager or supervisor can describe what a person holding a job must do to be successful. What would the jobholder's outputs be? Would customers have clear answers to their questions? Would decision makers in the organization have accurate and timely data from this person? The analyst can identify the activities necessary to create these outputs.

- A supervisor or job analyst can review company records related to performing the job for example, work orders or summaries of customer calls. These records can show the kinds of problems a person solves in the course of doing a job.32

After gathering information, the next thing to do is list all the activities and evaluates which are essential duties. One way to do this is to rate all the duties on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is most important. A rating scale could also rank the tasks according to how much time the person spends on them. Perhaps the ratings will show that some tasks are desirable but not essential. Gathering information from many sources helps to verify which tasks are essential. Perhaps the jobholder is aware of some activities that others do not notice. In other cases, he or she might perform activities that are merely habits or holdovers from a time when they were essential. When different people analyzing a job come to different conclusions about which activities are essential, the person writing the job description should compare the listed activities with the company's goals and work flow to see which are essential. A group discussion also may help categorize tasks as essential, ideal, and unnecessary. From these sources, the writer of the job description obtains the important elements of the description:

- Title of the job. The title should be descriptive and, if appropriate, indicate the job's level in the organization by using terms such as junior, senior, assistant, and executive.

- Administrative information about the job. Depending on the company's size and requirements, the job description may identify a division, department, supervisor's title, date of the analysis, name of the analyst, and other information for administering the company's human resource activities.

- Summary of the job, focusing on its purpose and duties. This summary should be brief and as specific as possible, including types of responsibilities, tools and equipment used, and level of authority (e.g., the degree of authority and responsibility of the jobholder—how closely the person is supervised and how closely the person supervises others or participates in teamwork).

- Essential duties of the job. These should be listed in order of importance to successful performance of the job and should include details such as physical requirements (e.g., the amount of weight to be lifted), the persons with whom an employee in this job interacts, and the results to be accomplished. This section should include only duties that the job analysis identified as essential.

- Additional responsibilities. The job description may have a section stating that the position requires additional responsibilities as requested by the supervisor.

- Job specifications. The specifications cover the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics required for a person to be qualified to perform the job successfully.

These may appear at the end of the job description or as a separate document.33 Whenever the organization creates a new job, it needs to prepare a job description, using a process such as the one detailed in the HR How-To box. Job descriptions should then be reviewed periodically (say once a year) and updated if necessary. Performance appraisals can provide a good opportunity for updating job descriptions, as the employee and supervisor compare what the employee has been doing against the details of the job description. When organizations prepare many job descriptions, the process can become repetitive and time-consuming. To address this challenge, a number of companies have developed software that provides forms into which the job analyst can insert details about the specific job. Typically, the job analyst would use a library of basic descriptions, selecting one that is for a similar type of job and then modifying it to fit the organization's needs. Organizations should provide each newly hired employee a copy of his or her job description. This helps the employee to understand what is expected, but it shouldn't be presented as limiting the employee's commitment to quality and customer satisfaction. Ideally, employees will want to go above and beyond the listed duties when the situation and their abilities call for that. Many job descriptions include the phrase and other duties as required as a way to remind employees not to tell their supervisor, "But that's not part of my job."

Job Specifications

Whereas the job description focuses on the activities involved in carrying out a job, a job specification looks at the qualities of the person performing the job. It is a list of the competencies that are; knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics associated with effective job performance. Knowledge refers to factual or procedural information necessary for successfully performing a task. For example, this course is providing you with knowledge in how to manage human resources. A skill is an individual's level of proficiency at performing a particular task the capability to perform it well. With knowledge and experience, you could acquire skill in the task of preparing job specifications. Ability, in contrast to skill, refers to a more general enduring capability that an individual possesses. A person might have the ability to cooperate with others or to write clearly and precisely. Finally, other characteristics might be personality traits such as someone's persistence or motivation to achieve. Some jobs also have legal requirements, such as licensing or certification.

In developing job specifications, it is important to consider all of the elements of the competencies. As with writing a job description, the information can come from a combination of people performing the job, people supervising or planning for the job, and trained job analysts. Accurate information about competencies is especially important for making decisions about who will fill a job. A manager attempting to fill a position needs information about the characteristics required, and about the characteristics of each applicant. Interviews and selection decisions should therefore focus on competencies. The identification of competencies is also being implemented widely in the public sector. These competencies include detailed descriptions, such as the behaviors as well as the knowledge, skills, and abilities associated with each competency. Competencies identified for middle managers in the federal public sector include intellectual competencies (e.g., cognitive capacity); management competencies (e.g., teamwork); relationship competencies (e.g., communication); and personal competencies (e.g., stamina or stress resistance).

Fleishman Job Analysis System

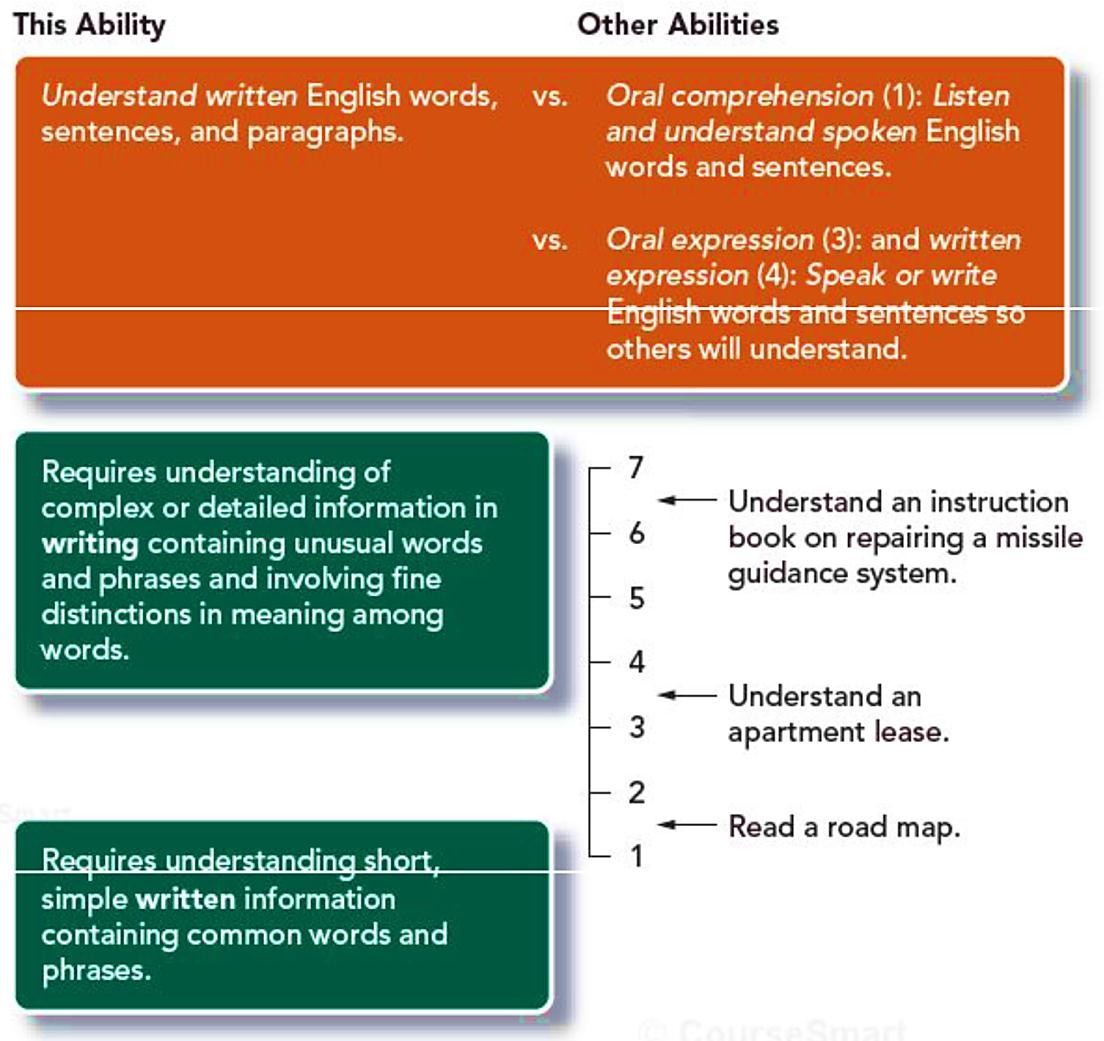

To gather information about worker requirements, the Fleishman Job Analysis System asks subject-matter experts (typically job incumbents) to evaluate a job in terms of the abilities required to perform the job.34 The survey is based on 52 categories of abilities, ranging from written comprehension to deductive reasoning, manual dexterity, stamina, and originality. As in the example in Figure 13, the survey items are arranged into a scale for each ability. Each begins with a description of the ability and a comparison to related abilities. Below this is a seven-point scale with phrases describing extremely high and low levels of the ability. The person completing the survey indicates which point on the scale represents the level of the ability required for performing the job being analyzed.

Written Comprehension

This is the ability to understand written sentences and paragraphs. How written comprehension is different from other abilities:  Figure 13 : Example of Ability from the Fleishman Job AnalysisSystem35

Figure 13 : Example of Ability from the Fleishman Job AnalysisSystem35

When the survey has been completed in all 52 categories, the results provide a picture of the ability requirements of a job. Such information is especially useful for employee selection, training, and career development.  35 Brown, David. HR Pulled in Two Directions at Once. 2004 : HR Reporter

35 Brown, David. HR Pulled in Two Directions at Once. 2004 : HR Reporter

Importance of Job Analysis

Job analysis is so important to HR managers that it has been called the building block of everything that HR does. The fact is that almost every human resource management program requires some type of information gleaned from job analysis:36

- Work redesign. Often an organization seeks to redesign work to make it more efficient or to improve quality. The redesign requires detailed information about the existing job(s).

- Workforce planning. As planners analyze human resource needs and how to meet those needs, they must have accurate information about the levels of skill required in various jobs, so that they can tell what kinds of human resources will be needed.

- Selection. To identify the most qualified applicants for various positions, decision makers need to know what tasks the individuals must perform, as well as the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities.

- Training. Almost every employee hired by an organization will require training. Any training program requires knowledge of the tasks performed in a job, so that the training is related to the necessary knowledge and skills.

- Performance appraisal. An accurate performance appraisal requires information about how well each employee is performing in order to reward employees who perform well and to improve their performance if it is below expectations. Job analysis helps in identifying the behaviors and the results associated with effective performance.

- Career planning. Matching an individual's skills and aspirations with career opportunities requires that those responsible for developing career planning processes know the skill requirements of the various jobs. This facilitates matching of individuals to jobs in which they will succeed and be satisfied.

Job analysis supports several of these activities when it comes to automating major job duties, as described in the e-HRM box. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) has an automated resource, a database that identifies the functions and competency requirements of specific RCMP jobs; it integrates information about jobs to various HR functions. For example, the database links "Job Profiles," materials to help understand what the job is all about, with "Development Activities," which provide information about formal learning opportunities including workshops, online courses, and offline resources such as articles and videos. The link "Problem-Based Learning" leads to scenarios that test one's skills and "Performance Management" allows employees and their supervisors to get assistance in determining competencies for further development.

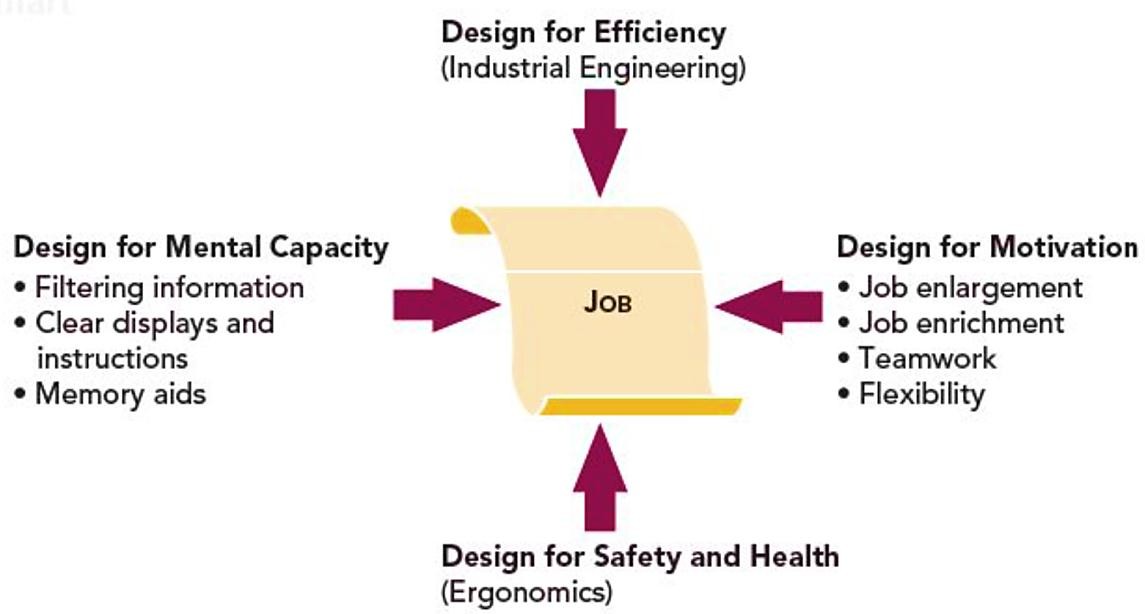

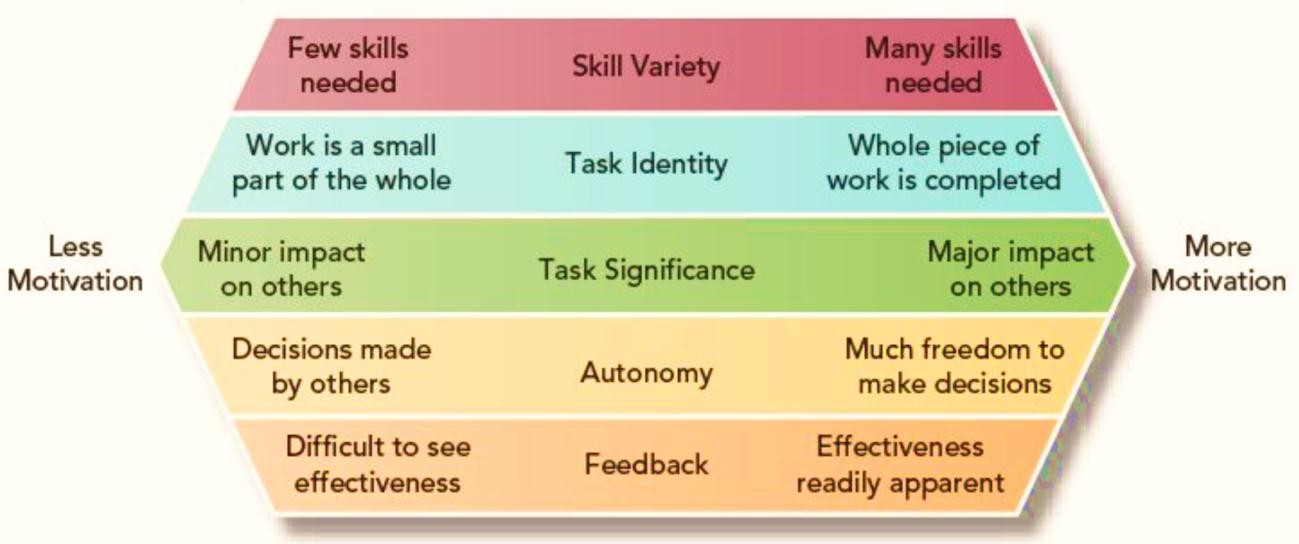

3.2. Job Design