Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA) of Food Waste

Info: 5335 words (21 pages) Dissertation

Published: 10th Dec 2019

Tagged: Food and Nutrition

Abstract

In recent years, food waste has become a global concern for governments and their citizens. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), it is estimated that, in 2011, one third of the food produced for human consumption was wasted. In Canada, the amount of food waste is similar; approximately 40% of food produced for human consumption is being wasted yearly. Food waste goes far beyond environmental and economic impacts. As global food security continues to decrease, food waste also includes social impacts. The Office of Sustainability in the University of Saskatchewan in collaboration with Marquis Culinary Centre (MCC) has made it their quest to increase the sustainability of their operations. The MCC is now a key sustainability player in employing sustainable practices to tackle food waste in its daily operations. Food waste is an increasing concern for the university. In March 2017, a one-week food waste audit revealed waste of 2,330.97 kg of food (Gilliard, 2017). Earlier, in February 2016, the University of Saskatchewan bought a food waste dehydrator to help reduce food waste on campus (Glazebrook, 2017). The university’s administration, the Office of Sustainability and the Facility Management Division have all indicated their intention to reduce food waste.

The purpose of this paper is as follows: First, to apply the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA) frameworks to examine food products and to understand food waste at the University of Saskatchewan. I chose to use LCA since there are environmental impacts associated with food products throughout their life cycle. However, because the LCA is limited in scope and only addresses the environmental impacts, I was forced to examine another framework called Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA). This framework was also limited in scope, especially in its ability to address the food waste at Marquis Culinary Centre (MCC). Since food waste is a sustainability issue, it encompasses the three pillars of sustainability: environmental, social and economic. Applying these two frameworks is useful in examining two of these pillars: the environmental and social perspective; however, both frameworks chose to omit the economic impacts, which is also a vital area of sustainability. Both frameworks have their benefits because they offer some insights into the problem. However, I suggest tackling food waste from a holistic sustainability perspective using the LCA and SLCA with a combination of other tools, such as cost-benefit analysis, multi-criteria analysis, economic and carbon footprint framework.

Introduction

In recent years, food waste has become a global concern for governments and their citizens. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that, in 2011, one third of food produced for human consumption was wasted (FAO, 2011). In fact, according to the Green Optimistic, the planet’s annual food waste is equivalent to 50% of its yearly cereal crops (Pullen, 2016). In Canada, the amount of food waste is similar; approximately 40% of food produced for human consumption is being wasted yearly (Gooch et al.,2010). Canadians waste more than seven billion kilograms of edible food annually (Tamburri, 2014). At the household level, Canadians waste almost 50% of the total food produced (Coulter-Low, 2016).

The waste of food in Canada has economic, environmental and social impacts. Economic losses due to food waste and losses were valued in 2010 at $27 billion, increasing to $31 billion in 2014 (Richardson, 2017). Food retail stores account for 11% of the total identified waste stream (Gooch et al., 2010).

Environmental losses are a waste of resources used in food production, including land, water, and energy (FAO, 2011). These wasted resources would be better used for the production of food for people who are hungry in the world (D. Evans, 2014). In Canada, 850,000 people use food banks on a monthly basis, yet food waste is increasing (P. Evans, 2014).

Food waste contributes to air pollution such as the release of dangerous methane gasses from decomposing food coming from landfills and water pollution due to the runoff from landfills. (Lam, 2010). Methane, a greenhouse gas that is a by-product of food decomposition in landfills, is 20% more harmful to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, and food waste accounts for approximately 40% of landfill waste (Allan, 2014).

Food waste at the University of Saskatchewan is an increasing concern for the Office ofSustainability and the MCC. These offices are working together to reduce food waste, but to be effective their strategies need to be informed by data that assess food waste from a sustainability standpoint and, examine food products along the food supply chain to better understand how food waste is created along the product’s life cycle.

Although food insecurity and food waste are continuing to increase across the globe, food waste is still an under-researched area for social scientists (Evans et al., 2013). A report in 2013 from the Guelph-based Provision Coalition reported that there is inadequate data on food waste and its causes in Canada (Uzea et al., 2013).

Marquis Culinary Centre (MCC) is now a key sustainability player in employing sustainable practices to tackle food waste in its daily operations which includes the following: going trayless in its dining room; offering a variety of vegetarian and vegan dishes; using reusable ware in its dining area; employing sustainable cooking techniques such as batch cooking; purchasing food from local vendors and student operations, such as the Horticulture Club and the College of Agriculture and Bioresources Rooftop Garden; using biodegradable cutlery, plates and platters for catering offerings; advertising sustainable events such as Local Food Month, the annual Sustainable Gourmet meal, and International Street Food Week; offering a reusable mug discount at all Consumer Services outlets; and partnering with Facilities Management and the Office of Sustainability to purchase and implement a food waste dehydrator as a pilot project to reduce food waste going to landfill (Office of Sustainability, 2016). Despite these various sustainable practices implemented by MCC, there is still room for improvement in reducing food waste on campus.

The purpose of this paper is to apply the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA) frameworks to examine food products to understand food waste at the University of Saskatchewan. The paper is divided into the following sections: first, I do an overview of LCA before applying LCA to the problem; second, I do an overview of SLCA; I, then, apply SLCA to the problem; third, I compare the two frameworks as they relate to my problem; and, fourth, I examine limitations of both frameworks.

Overview of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Framework

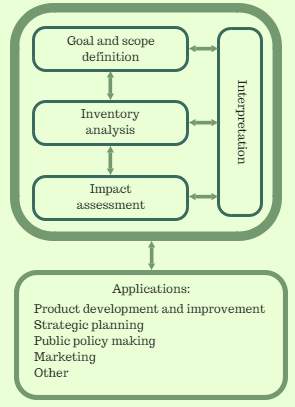

According to Curran (2013), “Life Cycle Assessment is an analytical tool that captures the overall environmental impacts of a product, process or human activity from the raw material acquisition, through production and use, to waste management” ( p. 1). LCA has various definitions and names. According to Roy et al. (2009), “LCA” [is] also called eco-balancing, resource and environment. LCA framework has four main stages. See Figure 1 below, which describes the LCA Framework’s four stages.

LCA Framework

LCA Framework

Figure 1: The Stages of LCA Framework (Roy et al., 2009)

- Goal Scope and Definition – This is the most significant part of the study that aims, first, to state the purpose of the study, second, to describe the expected results, third, to describe the functional units, and, fourth, to examine the system boundary. (At this stage, users can decide what to include in the study and what not to include.)

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis – This phase is the most labor-intensive stage as data are collected. This stage looks at all the inputs and the outputs of the product or process.

- Impact Assessment – This is the stage in which the potential environmental impacts are identified based on the inputs and outputs in the life cycle inventory and their impact on products or processes throughout the life cycle

- Interpretation – This stage interprets the results (based on the inventory and impact stage), keeping the goal scope and definition in mind (Roy et al., 2009).

Application of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

The issue here is examining food products to understand food waste at the University of Saskatchewan campus. To effectively understand how food is being wasted, one has to look at food products from the whole food supply chain (FSC) – from fork, to farm to landfill – as well as how food waste is created in the first place along the food supply chain, such as primary production, transport and storage, processing, distribution, consumption and waste handling (Corrado et al., 2017). One method to evaluate food waste is the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). This method is used to in several ways. First, it can be used to look at the diverse uses of resources along the food supply chain, such as product design, raw material extraction and processing, product manufacture, packaging/distribution, product use/consumption and end of life/disposal/ new life (UN Environment, 2017). Second, LCA can be used to ascertain where in the products or processes’ life cycle the highest environmental impacts are occurring (Corrado et al., 2017). Third, it can be used to choose potential alternatives to raw material, packaging, and waste management initiatives. Applying LCA to food waste at the University of Saskatchewan Campus, I will break down the problem into the following stages of LCA and address each: Goal scope and definition, life cycle inventory (LCI) analysis, life cycle impact assessment and life cycle assessment.

Goal Scope and Definition

The goal of this assessment is to determine environmental impacts of food products along the food supply chain to better understand how food waste is created along the product’s life cycle. The study area I will be looking at is Marquis Culinary Centre (MCC) on the University of Saskatchewan Campus. MCC tries its best to support local farmers with 13% of its food purchased locally (Office of Sustainability, 2016). The functional unit in this scenario is looking at the environmental impacts of one ton of organic food waste over a period of five years.

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

This step involves looking at all the inputs such as resources (raw material, energy, labour and land) needed in processing food products. It then looks at the associated outputs of the inputs, such as emissions to land (excess solid waste in the landfill), air (airborne emissions), water (water effluents), and other environmental impacts (Sustainable Facilities Tool, 2006). The aim of the LCI analysis is to obtain data to quantify the number of inputs and outputs throughout the product’s life cycle. By quantifying the number of inputs and outputs, decision makers can ascertain the section along the supply chain that has the highest environmental impact. In the case of MCC, the life cycle stages include the last step of production, distribution and storage, consumption and final disposal of what is left uneaten. However, in MCC’s case, the LCA would be limited to looking only at the last step of the production stage through the end of life of the food product. This is a limitation of the LCA, since food waste occurs from early stages in the food chain. LCA does not account for the complete food waste during the product’s whole life cycle in the case of MCC.

Life Cycle Impact Assessments

The life cycle impact assessment seeks to understand all the inputs and outputs throughout the product’s life cycle and their potential environmental impacts (Srinivas, 2010). Impact assessment consists of the following categories: classification, characterization, normalization, and valuation (Roy et al., 2009).The potential global effects would include global warming potential, acidification potential, eutrophication potential and photochemical ozone creation potential (Padeyanda et al., 2016). In the case of MCC, all these global effects would apply. Some of these global effects could be obtained from Canadian university existing studies that have a similar population as the U of S.

Interpretation

This stage involves interpreting the results of the life cycle inventory analysis, taking into account the goal of the study (Srinivas, 2010).

LCA has its benefits: First, it helps decision makers identify the highest impact areas along the product’s life cycle. By doing this, decision makers are able to make improvements in areas that need immediate attention to reduce their impacts. In MCC’s case, the LCA could provide some useful insights for the restaurant manager on how food waste is created at the various stages of the food product life cycle. Second, LCA is used to choose better alternatives, such as raw material acquisitions, transport of raw materials, packaging, and waste management initiatives. MCC could choose to purchase from a supplier that employed sustainability practices in its operations to reduce impacts to the environment. Third, LCA can help decision makers to make a more informed decision.

However, despite LCA’s benefits, it has its limitations as well: First, LCA mainly focuses on the environmental impacts, thus excluding the social and economic impacts (Reap et al., 2008). Second, LCA highly focuses on the production side of the product’s life cycle. Third, LCA is highly subjective, since most of the interpretation is left up to the person that uses it (Reap et al., 2008) . Also, the LCA is limited in addressing food waste that occurs at the raw material and the transport of the raw material phase, before the food is delivered to Marquis Culinary Centre. It would be difficult for restaurant managers to obtain this data since it is out of their scope. Therefore, the LCA would only partially address the issue, due to the exclusion of early stage of primary production, transport and storage before food is delivered to Marquis Culinary Centre.

Overview of Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA) Framework

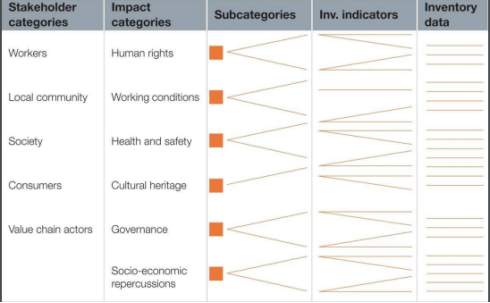

According to one source, “A social and socio-economic Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) is a social impact (and potential impact) assessment technique that aims to assess the social and socio-economic aspects of the product[s] and their potential positive and negative impacts along their life cycle encompassing extraction and processing of raw material; manufacturing; distribution; use; re-use; maintenance; recycling; and final disposal” (UNEP Setac Life Cycle Initiative, 2009, p. 37). SLCA can be used alone,or complement the LCA. SLCA has the same four main stages as LCA (goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment and interpretation. However, differences lie in the goal and scope definition, as SLCA is all about the social impacts on the stakeholders involved in the product or processes life cycle. Additionally, the data collected in the inventory stage include the impact on stakeholders such as employees/workers, the society, and the local community (UNEP Setac Life Cycle Initiative, 2009). Figure 2 below shows the elements of the SLCA framework.

SLCA Framework

Figure 2: SLCA framework (Sustainable Facilities Tool, 2006)

Application of Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA)

Because of the limited scope of the LCA, I have looked at another framework called Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA). SLCA can be used as a stand-alone tool or it can complement the LCA. SLCA shares the same general ISO framework, which includes (goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory analysis, life cycle assessment and interpretation); however, there are differences in what both frameworks seek to achieve. In contrast to LCA, SLCA, first, focuses mainly on the social well-being of the stakeholders involved (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015). Second, it looks at positives as well as negative impacts on the product’s life cycle (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015). SLCA include elements such as stakeholder’s categories and impact categories. The stakeholders categories include workers, the local community, society, consumers, and value chain actors, while the impact categories are human rights, working conditions, health and safety, cultural heritage, governance and socio-economic repercussions (Foolmaun & Ramjeeawon, 2013). In the case of Marquis Culinary Centre, SLCA might not be applicable to the restaurant manager, largely because it is outside the scope of people who work in the food industry. Also, it would be hard to quantify some social and health issues, which this framework is limited in.

Comparison of Life Cycle Assessment and Social Life Cycle Assessment Frameworks

Methodologies

Even though LCA and SLCA share the same ISO framework stages (goal and scope definition, life cycle analysis, life cycle impact assessment and interpretation), the distinct stages of each framework set them apart. These include the purpose of the study and information the framework seeks to obtain. LCA is focused on the product or processes environmental impacts. LCA, therefore, examines all the negative environmental impacts that are associated with food products throughout their life cycle and aims to reduce these impacts. In contrast, Social Life Cycle Assessment seeks to identify both the positive and negative impacts on the stakeholders throughout the product life cycle.

Benefits of Both Frameworks

The benefits of LCA are as follows: First, it examines the environmental impacts of the food product during the whole life cycle. Second, LCA determines the environmental hotspots of the food product during the life cycle. Identifying the hotspots in the frameworks allows the decision maker to implement mitigations to reduce these impacts on the environment. Third, it helps to identify the area of the life cycle where the most improvement is needed. The benefits of SLC are as follows. First, the framework aims to determine the social impacts of a product throughout its life cycle on key stakeholders. Second, SLCA looks at both the negative and positive impacts of a product or service. This is helpful to the university’s stakeholders. For example, currently, Marquis Culinary Centre is giving away gift cards to the food bank here on campus for food insecure students (M. Tan, personal communication, November 1, 2017). While this is good for the campus community, MCC needs to look at large-scale donating to the food centers in the province since it produces such a high volume of food waste.

Limitations of Both Frameworks

Both frameworks have limitations. These can be categorized into similar and different limitations. The similarities of both frameworks are as follows: First, both LCA and SLCA employ the ISO framework (goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory analysis, life cycle impact assessment and interpretation); however, there are some distinct features of SLCA in each phase; second, limited data is available for both frameworks; third, both frameworks are expensive and time-consuming to collect the data needed; fourth, both frameworks provide valuable data to support the decision-making process, but neither provide an answer about which product or process to produce; fifth, both frameworks determine hotspots areas so as to help develop mitigation strategies to reduce impacts (UNEP Setac Life Cycle Initiative, 2009).

The differences of both frameworks’ limitations are as follows: First, LCA mainly focuses on the environmental impacts, while SLCA focuses on the social and socio-economic impacts; second, LCA uses mostly quantitative data, while SLCA uses qualitative and semi-quantitative data; third, LCA’s attention is mainly on the environment, while SLCA emphasizes stakeholder involvement; fourth, LCA focuses on the entire life cycle of the product or service from the acquisition of raw material through disposal, while the bulk of SLCA studies do not include the “use” phase; sixth, LCA focuses mainly on the negative environmental impacts, while SLCA focuses on both positive and negative social impacts (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015 & UNEP Setac Life Cycle Initiative, 2009).

Limitations of LCA are:

- LCA is not a stand-alone tool; it has to be used in conjunction with other tools (Curran, 2013).

- LSA has difficulty defining the boundaries and scope – what to include and what not to include in the scale of the study (Sustainable Facilities Tool, 2006).

- Limited data is available (Curran, 2013).

- There are methodology drawbacks, and the guidelines of the ISO frameworks can be interpreted differently by practitioners (Curran, 2013).

- It focuses mainly on the environmental impacts and eliminates the economic and social impacts. This is due, in part, to the ISO guidelines for LCA, which are bound to environmental effects (Heijungs et al. 2009).

- It focuses mainly on the negative environmental impacts.

- There is a lack of an agreed upon international standardization by LCA practitioners and modelers (Roy et al. 2009).

Limitations of SLCA are:

- Limited quality inventory data is available since SLCA is relatively new (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015).

- No global social database is available.

- ISO provides a general guideline for SLCA; however, much is left to the interpretation of the people who use it.

- SLCA does not include the use phase of a product (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015).

- It omits the economic and environmental impacts.

- It is subject to bias in terms of which stakeholders to include and not include.

- It is highly subjective. The UNEP/SETAC guidelines are unclear and may be interpreted differently by people who use them (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015).

- The social dimension is difficult to quantify. No internationally agreed on scientific impact assessment method is used (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015).

- The various methods proposed by SLCA can produce different outcomes (Chhipi-Shrestha et al., 2015).

- It uses mostly a top-down approach that excludes the impacts on the people in the local community.

Conclusion

Both frameworks – LCA and SLCA – are limited for examining food products to understand food waste on the University of Saskatchewan campus. These frameworks have some benefits in that they are looking at the problem from different perspectives; however, they don’t solve the problem. Based on the literature I read on these frameworks, they often seem abstract and limited in what they can and cannot do. Moreover, neither consider all three of the sustainability pillars.

To accomplish sustainable development, not only environmental and social impacts need to considered but also the economic impacts of food waste on the environment and the well-being of humans. Food waste is a sustainability issue; therefore, it should be addressed using broader sustainability thinking which comprises the three pillars of sustainability. Reducing food waste reduces environmental impacts and social impacts. It also increases food security and has a distinct economic impact, such as decreasing the purchasing cost of food. It would be worthwhile to look at the economic and social costs of the stages of the life cycle that exist in MCC and to look at other approaches, such as a cost-benefit analysis, multi-criteria analysis, economic and carbon footprint framework.

References

Allan, M. (2014). Food Waste – Residence Programs & Events and Opportunities at Western University, London Ontario Canad. Retrieved July 23, 2017, from https://rezlife.uwo.ca/articles_foodwaste.cfm

Chhipi-Shrestha, G. K., Hewage, K., & Sadiq, R. (2015). “Socializing” sustainability: a critical review on current development status of social life cycle impact assessment method. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 17(3), 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-014-0841-5

Corrado, S., Ardente, F., Sala, S., & Saouter, E. (2017). Modelling of food loss within life cycle assessment: From current practice towards a systematisation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 847–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.050

Coulter-Low, S. (2016). New Infographic: Reducing Food Waste in Ontario and Canada « Sustain Ontario. Retrieved from https://sustainontario.com/2016/06/08/30229/news/new-infographic-reducing-food-waste-in-ontario-and-canada

Curran, M. A. (2013). Life Cycle Assessment: A review of the methodology and its application to sustainability. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, 2(3), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coche.2013.02.002

Evans, D., Campbell, H., & Murcott, A. (2013). Waste Matters : New Perspectives on Food and Society. John Wiley & Sons.

Evans, P. (2014). Food waste costs Canada $31B a year, report says – Business – CBC News.

FAO. (2011). Global food losses and food waste – Extent, causes and prevention. Rome. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/mb060e/mb060e00.pdf

Food waste costs Canada $31B a year, report says – Business – CBC News. (n.d.). Retrieved April 23, 2017, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/food-waste-costs-canada-31b-a-year-report-says-1.2869708

Foolmaun, R. K., & Ramjeeawon, T. (2013). Comparative life cycle assessment and social life cycle assessment of used polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles in Mauritius. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18(1), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-012-0447-2

Gilliard, P. (2017). Assessing and Quantifying Food Waste on the University of Saskatchewan Campus: Developing a Comprehensive Food-Waste Reduction Plan. Unpublished research, University of Saskatchewan

Glazebrook, H. (2017). New dehydrator recycles campus food waste – News – University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved July 1, 2017, from https://news.usask.ca/articles/general/2017/new-dehydrator-recycles-campus-food-waste.php

Gooch, M., Felfel, A., & Marenick, N. (2010). Food Waste in Canada. Value Chain Management Centre, (November), 1–16. Retrieved from http://vcm-international.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Food-Waste-in-Canada-112410.pdf

Heijungs, R., Huppes, G., & Guinée, J. B. (2009). Life cycle assessment and sustainability analysis of products, materials and technologies. Toward a scientific framework for sustainability life cycle analysis. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 95, 422–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2009.11.010

Lam, Y. (2010). Why do UC Berkeley Students Waste Food at Dining Halls? Spring.

Office of Sustainability. (2016). Annual Sustainability Report.

Padeyanda, Y., Jang, Y.-C., Ko, Y., & Yi, S. (2016). Evaluation of environmental impacts of food waste management by material flow analysis (MFA) and life cycle assessment (LCA). Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 18(3), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-016-0510-3

Pullen, N. (2016). Food Waste Fast Facts – Why is Food Being Wasted – The Green Optimistic. Retrieved August 3, 2017, from https://www.greenoptimistic.com/food-waste-facts/#.WYNOp4TyvIU

Reap, J., Roman, F., Duncan, S., & Bras, B. (2008). A survey of unresolved problems in life cycle assessment. Part 1: Goal and scope and inventory analysis. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 13(4), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-008-0008-x

Richardson, N. (2017). Filling up our landfills: The facts on food waste and composting at Carleton – The Charlatan, Carleton’s independent newspaper. Retrieved from http://charlatan.ca/2017/01/filling-up-our-landfills-the-facts-on-food-waste-and-composting-at-carleton/

Roy, P., Nei, D., Orikasa, T., Xu, Q., Okadome, H., Nakamura, N., & Shiina, T. (2009). A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) on some food products. Journal of Food Engineering, 90(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.06.016

Srinivas, H. (2010). Defining Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), 1–3. Retrieved from http://www.gdrc.org/uem/lca/lca-define.html

Sustainable Facilities Tool. (2006). Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Overview – GSA Sustainable Facilites Tool. Retrieved November 26, 2017, from https://sftool.gov/plan/400/life-cycle-assessment-lca-overview

Tamburri, R. (2014). Canadians waste seven billion kilograms of food a year – The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/business-education/canadians-waste-seven-billion-kilograms-of-food-a-year/article19923151/

UN Environment. (2017). Benefits of Life Cycle Approaches – Life Cycle Initiative. Retrieved December 6, 2017, from https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/starting-life-cycle-thinking/benefits/

UNEP Setac Life Cycle Initiative. (2009). Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products. Management (Vol. 15). https://doi.org/DTI/1164/PA

Uzea, N., Gooch, M., & Sparling, D. (2013). Developing an Industry Led Approach to Addressing Food Waste in Canada, 1–38.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allRelated Content

All TagsContent relating to: "Food and Nutrition"

Food and Nutrition studies deal with the food necessary for health and growth, the different components of food, and interpreting how nutrients and other food substances affect health and wellbeing.

Related Articles

DMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this dissertation and no longer wish to have your work published on the UKDiss.com website then please: