Communication Procedures of Transportation Engineering Sector

Info: 26236 words (105 pages) Dissertation

Published: 20th Aug 2021

Tagged: EngineeringManagement

Figure 1: Highways Industry, (2017).

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” George Bernard Shaw.

Abstract

The importance of communication skills within transport engineering sectors cannot be underestimated. Transportation highway engineers are reliant upon their team members’ communication skills to enable them to work safely and effectively on complex projects, in challenging environments within tight time and budget constraints. Organisations working communication procedures supports every business function; and underpins successful project delivery, performance, and productivity, promoting effective teamworking communication and safety adherence (HSE, 2017; Madhukar, 2010).

The literature review explored communication models, methods, and procedures to gain understanding of what promotes or hinders effective working communication procedures. This included examining teamworking communication and organisational culture in transportation highway engineering teams. A study was conducted to determine whether working communication procedures affected the attitudes of transportation highway engineers.

Study results were analysed using a quantitative Likert scale, based on questionnaire responses from 43 transportation highway engineers. The study identified that a relationship exists between working communication procedures and engineers’ working attitude and that the engineers’ strength of attitude significantly correlated with their job position.

Implications and future directions for research linking attitudes to working communication procedures were discussed.

Keywords: Transportation engineering, highway engineering, groundworkers, teamworking, effective communication, attitude, communication models, public sector, leadership, followership, interpersonal skills, professional communication skills, Likert, safety, working procedures, relationships, education, culture, sub-culture.

Table of Contents

Page

Acknowledgements……………………………………………………i

Statement of Originality………………………………………………..ii

Abstract………………………………………………………….iii

Table of contents…………………………………………………..iv-vi

1. Introduction ……………………………………………………..1

1.1 Necessity of Research…………………………………………..3

1.2 Aims………………………………………………………4

1.3 Objectives…………………………………………………..4

2. Literature Review…………………………………………………..5

2.1 The engineering-communication relationship……………………………5

2.2 Communication models………………………………………….6

2.3 Communication in teams…………………………………………7

2.3.1 Interpersonal and intrapersonal communication……………………7

2.3.2 Leadership and followership………………………………..8

2.3.2.1 Effective followership………………………………..9

2.3.3 Motivation…………………………………………..10

2.4 Organisational Culture and teamworking in engineering……………………11

2.4.1 Organisational culture and subcultures…………………………13

2.5 Working communication procedures………………………………..14

2.5.1 Verbal and non-verbal communication…………………………15

2.5.1.1 Verbal communication………………………………15

2.5.1.2 Non-verbal communication……………………………16

2.5.2 Functions of working communication procedures………………….17

2.6 Communication skills and education………………………..19

3. Methodology…………………………………………………….21

3.1 Study Method……………………………………………….21

3.1.1 Study design and distribution……………………………….21

3.1.1.1 Design consideration………………………………..21

3.1.1.2 Independent and dependant variables…………………….23

3.1.2 Questionnaire participants………………………………..25

3.1.2.1 Hampshire County Council Highways: Areas Covered…………..26

4. Results…………………………………………………………27

4.1 Strength of attitude towards working communication questionnaire statements for all participants 27

4.2 Strength of attitude towards working communication questionnaire statements by job category: Managerial, Supervisor and Ground Operative 29

4.3 Strength of attitude towards working communication questionnaire statements by job position: Managerial/Supervisor and Groundworker/Contractor 32

5. Discussion………………………………………………………44

5.1 Study results observations……………………………………….44

5.2 Study observations summary……………………………………..46

5.2.1 Improving attitudes towards working communication procedures, is it necessary? …………………….. 46

5.2.1.1 Previous research………………………………….47

5.2.2 How can attitudes be improved towards working communication procedures? 47

5.2.2.1 Further considerations………………………………49

5.2.2.2 Future investment………………………………….49

5.3 Study Limitations……………………………………………..50

6. Conclusion………………………………………………………51

6.1 Recommendations…………………………………………….52

7. References………………………………………………………53

8. Appendices……………………………………………………..63

Appendix A: Professional Needs Model……………………………………..63

Appendix B: Sample Questionnaire Front Cover………………………………..64

Appendix C: Sample Questionnaire………………………………………..65

Appendix D: Questionnaire Statements, Likert Scale questions and participant responses …….66

Appendix E: Participants response to 9 individual Likert scale items by job position…………71

Appendix F: Questionnaire statement results frequency displayed as histograms…………..76

Appendix G: Ethics Review……………………………………………..81

Appendix H: Health & Safety Risk Assessment…………………………………83

Tables

Table 1. Questionnaire statements grouped by variables………………………….24

Table 2. Hampshire County Council Employees…………………………………25

Table 3. Frequency of results. N = 43……………………………………….28

Table 4. Likert scale attitude responses……………………………………..33

Table 5. Working Communication Procedure Statements – Independent variable aspects……..37

Table 6. One-way independent ANOVA test results: 3 Job Categories………………….39

Table 7. One-way ANOVA test results: 2 Job Positions…………………………….39

Table 8. T-Test results: 2 Job Positions………………………………………40

Table 9. Pearson’s correlation coefficient results: 2 Job Positions…………………….41

Table 10. Regression statistics results: 2 Job Positions…………………………….42

1. Introduction

One of the oldest engineering professions, civil engineering, incorporates a variety of major sub-disciplines, one of which is transportation engineering (Bugliarello, 1994. p. 290). Transportation engineering projects are mostly undertaken by public sectors that respond to the changing social infrastructure landscape (Horikawa & Guo, 2009, pp. 2-5).

Working within strained public sector budgets, transportation engineers are relied upon to continually manage the tense interface between ‘newly built and deteriorated assets’ (Kaewunruen, Sussman, & Matsumoto, 2016, pp.1-3), often resulting in the planning and design of modern infrastructure transportation systems being outpaced by urban growth. Whilst managing those compatibility issues, transportation engineers are expected to ensure transportation systems are operating safely and efficiently; providing risk management and robust monitoring of those systems (Kaewunruen et al., 2016, pp.1-3). Furthermore, natural disasters such as the increase of severe United Kingdom (UK) flooding events (Lavers et al., 2013), not only add to the existing infrastructure pressures but also significantly impact and threaten infrastructure stability (Dawson et al., 2016, p.4).

According to a roadway analytics report conducted by INRIX Research, the UK is facing the largest predicated traffic congestion cost of any other European country (Cookson, 2016, p.3). With economic health dependant on transportation systems and infrastructure (Allport, Brown, Glaister & Travers, 2008, p.12), the UK government is beginning to invest record amounts into road improvement schemes (Department for Transport, 2016), promising to ease some of the enormous pressure on highway transportation projects. Yet, Shane et al., (2009, pp.221-229) warn that within transportation engineering projects, costs are ‘consistently underestimated’, Flyvbjerg, Holm, & Buhl, (2002, p.8) agree, claiming that this underestimation occurs in 90% of all transportation infrastructure projects.

While acknowledging that transport projects in the UK can be notoriously difficult to manage where ‘major over-runs are seen as the rule, rather than the exception’, Allport et al., (2008, p.16) offer suggestions as what may contribute to project issues, arguing that within those turbulent working environments, successful project delivery happens because of ‘people and management processes’ not from trying to manage the technical aspects of the project. Shane et al., (2009, pp.221-224) support their viewpoint, maintaining that while management of technical and natural resources are important, effective cost management of transportation projects rely on the coordination of organisational and human resources. Shane et al., (2002, pp.221-224) identified 18 common project cost escalation factors within transportation engineering projects. Their study proposed that external cost escalation factors, such as inflation, can be predicted but not controlled, whereas internal cost escalation factors such as managers not sharing clear project information with their team and miscommunication between management and groundworker engineers, can be controlled by improving teamworking communication.

Transportation engineers who specialise in highway engineering, often work in teams and sub-teams known as engineering ‘groundworkers, crews or gangs’. Highway engineering teams are made up of a workforce that routinely include managers, supervisors, groundworkers and contractors. Close collaboration within those teams is needed for the successful completion of engineering projects (Association, 2017, pp.3-7), and efficient, effective collaboration within teams depend on the sharing of their expertise (Nunamaker, Briggs, and Romano, 2014, pp. 27-30; Jowers et al., 2016, pp.1-4). In other words, teamworking collaboration depends on the team members’ ability to communicate effectively with each another.

Although it is common knowledge that good communication within organisations and engineering teams are essential for project delivery, how to achieve and maintain good communication within teams can often be overlooked, the assumption being that this type of good quality communication will naturally occur within engineering teams (Doherty, 2015). With effective communication being critical to the success of engineering projects, engineers are routinely relied upon to have strong communication skills (Khan, 2014, pp.28-29; Dulevičius & Naginevičienė, 2005, pp.19-21).

McCuen, Ezzell, Wong, & Mongan, (2011, pp. 87-91), argue that engineering communication ‘has a value basis’ where poor communication within teams can hinder the success of engineering projects, impact productivity, and significantly increase risk factors. Their argument emphasises the engineers’ reliance on the quality of their team members’ communication skills to be able to work safely and effectively within projects. In addition, events such as the Challenger disaster (Arnold & Malley, 1988, pp.12-14; Dombrowski, 1992, pp.73-76) have drawn attention to the consequences of ineffective organisational communication, particularly between management and groundworker engineers. Therefore, it seems vital to consider what factors support good quality and effective interdisciplinary communication.

1.1 Necessity of Research

An extensive search of published journals, articles and books related to transportation and highway team communication covering a 30-year period, from 1987 onwards, revealed that communication skills for transportation engineers remains an under researched area. Furthermore, the literature dealing with what supports effective communication in other sectors of engineering (Lester, 2014, pp.371-380; Goleman, 2014, pp. 3-28; Turner, 2008, pp. 128-136) cater for project management engineers developing leadership skills.

As miscommunication between management and groundworker engineers can lead to project failures (Shane et al.,2002, pp. 221-224) and potentially cause injury or loss of life (Gudmestad, 2014, pp.55-60), it seems important to acknowledge the need to better understand what promotes effective interdisciplinary team communications and to investigate the impact of working communication procedures within transportation engineering teams.

1.2 Aims

This paper aims to investigate the effect of working communication procedures on transportation engineering staff and contractors, to gain insight of what may promote or hinder communication in teams, from the groundworker engineers to management levels.

1.3 Objectives

- To identify what is communication, how it relates to engineering practice.

- To explore what supports effective interdisciplinary team communications.

- To explore communication procedures impacts on productivity and project delivery.

- To explore organisational culture and identify potential barriers to communication.

- To investigate the impact of working communication procedures on transportation engineering teams.

2. Literature Review

2.1 The Engineering-Communication relationship

At first glance, the engineering-communication relationship may appear to be incompatible, with one part based in science, the other in the arts, and yet transportation engineers need to use interpersonal and teamworking communication skills within their daily work.

“Communication is the essence of science”. Frances Crick. (as cited by Garvey 2014, p.ix).

Derived from Latin ‘communis’, meaning to share, communication is the imparting and exchanging of information (Stevenson & Dictionaries, 2010, p.352), and is at the heart of effective engineering (Association, 2017, p.6). According to The Institution of Engineering and Technology (2017), good communication skills are essential to a successful engineering career. Expectations for engineers to have well-developed, strong communication skills is increasing, due to the rapid advancement of communication technologies; globally diverse interdisciplinary teams, and customer bases (The National Academy of Engineering, 2004).

Engineers are well known for possessing strong technical, analytical and problem solving skills alongside their ability to maintain high professional and ethical standards – all highly valued key attributes of engineers. Dulevičius & Naginevičienė, (2005, p.19) claim that although engineers may be technically competent, if the engineer lacks good communications skills necessary to transfer information, then this makes ‘the engineers excellent technical skills superfluous’ further demonstrating that engineers’ communication skills are critical tools for success. And Khan (2014, pp. 28-29) agrees, stating that ‘effective communication is critical to the success of engineering projects.’ Despite evidence that communication is so important to working engineers, limited data based information is available that supports better understanding of the ‘specifics of how and why communication is important’ for engineering professionals (Darling & Dannels, 2003).

Transportation engineers who specialise in highway engineering commonly work in very large multidisciplinary teams consisting of managers, supervisors, groundworkers and contractors. Often working on complex projects with both time and budget constraints, it seems highway engineers face a combination of pressures while working in challenging environments. Under those conditions, engineers need to rely on their teams’ ability to communicate effectively (Lester, 2014, pp.371-380). Which raises the question, what factors influence the efficacy of communication? Over time, many different types of communication models have been developed to answer this question.

2.2 Communication models

One of the earliest models used to explain human communication was attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle (350 B C). Since then other communication cycle models have been developed including Shannon-Weavers’ (1949) model, which although developed for telecommunications, introduced the concept of the sender or receiver encountering ‘noise’ or interference as a barrier to communication. This early linear model of communication was unable to identify what makes human communication effective. Wilbur Schramms’ (1954) interactive model of communication identified that for effective communication to take place, an encoder and decoder of information was needed to establish a communication cycle, and if they shared a field of experience, then effective communication could take place. Schramm’s model accounts for feedback although not for the continual fluidity of communication.

In contrast, Dean Barnlund’s (1970) transactional model of communication identifies each person as being a sender-receiver, not just a sender or a receiver, and accounts for communication being a creative, dynamic, continuous process, creating meaning. Barnlund identified barriers to effective communication he called filters, where individuals receive and interpret information based on their life experiences, background and culture. This suggests that how an individual perceives and interprets communication influences how they react to the communication. From the 1980’s, information processing models of communication closely mirrored the ongoing developments in both psychology and computer science fields (Hollnagel, Woods, & Woods, 2005, pp.14-20; Goodwin, 2005, p.411). Cognitive processing was no longer seen as being sequential but cyclical, with the receiver of communication being anticipatory and active rather than being a passive or simply a reactive participant. With the deeper complexities of working communication now being acknowledged, it was accepted that communication was closely connected with human performance due to humans being involved with and dependant on other humans in their interconnected working environments (Hollnagel et al., 2005, pp.16-20). Current research of communication models claim that working environment quality is an ‘essential determinant of psychological wellbeing’ (Fixsen et al., 2000; OECD, 2014, p.13), which can directly impact productivity (Morgeson, Garza, & Campion, 2012).

2.3 Communication in teams

A positive and supportive psychosocial work environment primarily involves ‘good quality, effective interpersonal and social communications within the workplace’ which can influence, and benefit teamworking behaviour(Gellman & Turner, 2012, p.1587). ICE (2017) state that it is vital engineers collaborate and communicate well with their team, as effective team collaboration improves project delivery (Gerrard & Kings, 2015; PMI, 2013).

This raises the question as to what makes team collaboration effective? According to Nunamaker et al., (2014, pp.27-30), effective collaboration within teams depend on the sharing of their expertise. However, McCuen et al., (2011, p.97) argue that good teamworking communication skills requires the engineer to be more than an effective technical communicator; that to share knowledge and work collaboratively in teams relies on the engineers’ interpersonal skills. Whitcomb & Whitcomb, (2013) strongly support this point, claiming that the space shuttle Challenger disaster was caused by ‘flawed interpersonal and technical engineering communication.’

2.3.1 Interpersonal and intrapersonal communication

‘Inter’ means between, and therefore interpersonal communication takes place between people whereas ‘intra’ means within, intrapersonal refers to the persons’ unseen, internal dialogue (West & Turner, 2010, p.8). Interpersonal skills used within working relationships are mostly goal directed communication interactions to influence and bring about a desired result (Hayes 2002; Lane 2009, p.5), which when driven by a range of personal agendas, has the potential to impede the two-way participative qualities of those communications (Hargie, Dickson, & David, 2014, p.5). Weisinger (1998) identified that intrapersonal competencies underpin effective interpersonal communication which promotes team cooperation because these competencies allow team members to maintain and practice emotional self-regulation, and good levels of self-awareness while pursuing their goals and objectives. Yost & Tuckers’ (2000, p.101), study promotes the idea that to develop more ‘satisfied and successful teams,’ communication skills training and development need to take account of how to develop and promote team members’ emotional intelligence skills. Riemer (2007) agree that for engineers of the future, emotional intelligence has an important role to play in strengthening team communication.

2.3.2 Leadership and followership

According to Dixon, Mercado, & Knowles, (2013) professional leadership communication skills development within engineering sectors do not go far enough towards strengthening interdisciplinary team communication. They propose that this is because the vast majority of individual professional development is focused on developing the engineers’ leadership skills to manage a team of engineers, and yet promoting leadership communications does little to promote effective followership skills. Fielding & du Plooy-Cilliers, (2014, p.12) support this view, highlighting that workers are no longer prepared to ‘just take orders’, forcing managers to move away from a leadership driven, one-way style of communication, and adopt a leadership role that incorporates two-way communication. These viewpoints would appear to mirror the ongoing developments in communication model theory (Morgeson et al., 2012), giving rise to a new way of considering the connection between engineering working communication procedures and interdisciplinary team communication.

Chaleff (2009), cited by Dixon et al., (2013) reports that the leadership process is a partnership between leaders and followers. Two-way communication between leaders and followers has become steadily more popular since the 1980’s when advancements in communication models recognised the value and importance of establishing effective communication cycles within interdisciplinary teams (Hollnagel et al., 2005, pp.16-20).

Leadership skills are consistently more highly valued and recognised than followership skills; which Kelley (2008, p.11) referred to as a ‘leadership-centric’ viewpoint. An internet search using Google search engine supported this theory, returning approximately 10,000 leadership results for every 1 followership result. The ratio of these results may represent just how little attention is given to followership within organisations. Baxter, (2015) argues that followership has been less studied because followers are assumed to be passive, blindly following the leader, with leaders being the ones contributing to organisational success. And yet followers represent the majority of people working within those organisations, contributing 80% to the success of those organisations (Kelley, 1992; cited by Hall and Densten, 2002).

Hackman & Johnson, (2013, p.365) define followership as being ‘the discipline of supporting leaders to lead well’. Followers are not simply subordinates in an inferior position within a hierarchy structure that are expected to submit to and blindly follow orders from the leader (Hollnagel et al., 2005). Instead, they follow the leader not because they have to, but because they want to lead themselves, often towards the needs of the organisation (Kelley, 2008, pp.5-16). In this way, followership facilitates an important process of collaboration between followers and leaders to ‘optimise performance towards achieving organisational objectives’ and support teamwork communications (Chaleff, 2009).

2.3.2.1 Effective followership

Hackman & Johnson, (2013) propose that followers are proactive and can encourage and inspire leaders to change course which also supports Kelleys’ (2008, p.11) argument stating that leaders are ‘malleable products of cumulative followership actions’ which suggests that followers must also be malleable products of cumulative leadership actions. Brumm & Drury, (2013) claim that a statistically significant relationship exists between a followers’ perception of the leaders planning behaviours, with the empowerment of positive follower behaviours; warning that, if followers are not clearly informed of planning and goal setting, they are less likely to consider themselves involved in these aspects, leading to poor follower behaviours which are harmful to productivity and project delivery. Best practice in long term project planning is therefore connected to the followers’ level of support of organisational goals and leaders.

Chaleff, (2009, pp.1-15) states that an effective follower balances and supports dynamic leadership by being highly supportive and participative, relying on critical thinking and courageous conscience, yet also able to challenge and question the leader, to impart ethical and safe judgements. Chaleff, (2009) points out that empowered followers challenge leaders and while this may not be easy for leaders to manage, it is in the projects best interest in the longer term for leaders to be available and open to receiving feedback in a non-defensive way that ‘invites creative challenge’.

Hackman & Johnson, (2013) stress that this type of follower to leader communication will not happen without ‘leaders and an organisational culture that support this relationship’. Whitcomb & Whitcomb, (2013) strongly agree with the importance of the need to develop organisational cultures that support courageous followership and argue that the space shuttle Challenger disaster occurred because project engineers concerns about technical issues and further concerns about the impact of cold weather were either ‘not received with enough accuracy’ by NASA officials or possibly ‘expressed inadequately’. This leads to the question of what can encourage and support positive, empowered communication and behaviour in organisations?

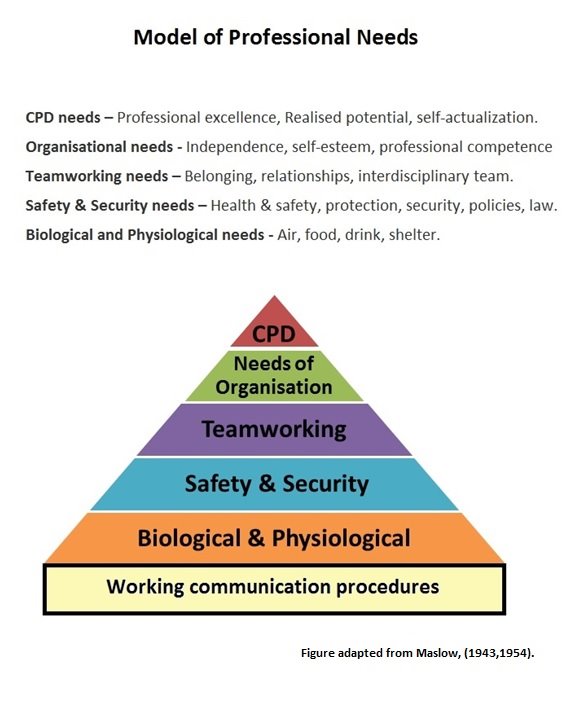

2.3.3 Motivation

Pritchard (2015) acknowledges that to achieve a ‘win-win scenario’ with staff, managers need to work in a collaborative way to cultivate and support true motivational behaviours to emerge within the team. Herzberg (2005) warned that managers who try to dominate and control their team may achieve compliance and get the job done although this is not the same as ‘true motivation.’ Pink (2011) agrees with Herzberg claiming that management is out of date in assuming that its main purpose is to ‘monitor and control employees’ and that motivation can best be produced by providing opportunities for ‘autonomy, mastery (learning) and self-actualisation.’ Maslows’ (1943,1954) hierarchy of needs is a commonly referred to model of human motivation theory, represented as a layered pyramid where each layer represents a basic human need, organised in a hierarchy structure. The model proposes humans are firstly motivated to satisfy their basic survival needs, before being able to seek to satisfy other needs such as belongingness, self-esteem and self-actualization.

Engineers have a range of professional needs, that would in theory need to be satisfied to enable engineers to display optimal performance behaviours within an organisational context (Kenrick et al., 2010). Engineers need to be fit for work; have safety in place to perform their duties, to work effectively as part of a team to complete projects, to feel a part of the organisation to support citizenship/followership behaviours and need to be able to reach their professional potential.

Herzberg (2005) expanded on Maslows’ motivational needs theory, proposing that ‘motivation is more than the absence of demotivation.’ Herzbergs (2005) study of engineers identified what he called hygiene factors that can prevent demotivation, but do not tend to support long-term motivation of employees. These factors Include things such as good working conditions and adequate salary. In contrast, factors such as opportunities for advancement, promotion, and feeling a valued part of the organisation supports long-term motivation and good teamworking attitudes (Herzberg, Mausner & Snyderman, 2011). In this way, engineers’ professional needs can be supported by the organisational culture and working communication procedures.

Organisational policies that support organisational culture may only be partially effective if those policies are not converted into practiced organisational values. Bateman & Organ, (1983) describe citizenship behaviours as ‘being able to lubricate the social machinery of the organisation’ which suggest that engineers can both negatively and positively contribute to their working environment and influence the wider organisational culture.

2.4 Organisational culture and teamworking in engineering

‘We ought to blame the culture, not the soil’. Alexander Pope. (Pope, 2001, p.109).

Organisational culture is the collection of ‘attitudes, values, goals and practices that characterise an organisation’ (Kitchin & Kitchin, 2010, p.25). The interest in why organisational culture impacts teamworking communication and behaviours became more popular since the 1970’s when academics started to take interest in what made Japanese manufacturing firms more productive and successful than other countries (Kitchin & Kitchin, 2010, p.25). These research interests made the important connection between how organisational culture influences teamworking attitudes and ultimately productivity.

A study by Francis (2012), examined how organisational culture can impact civil engineers discovered that engineers who perceived their organisations culture to be unsupportive had lower organisational commitment, had higher intentions to leave their job and reported reduced life satisfaction. Bianchi (2015) stresses that within interdisciplinary teams, the organisational culture impacts interpersonal relationships, adding that, how people interpret their psycho-social environment determines job satisfaction and organisational citizenship commitment.

Bateman & Organ (1983) use the term citizenship to represent belonging to and taking part in organisational civilization and culture. They identify a causal connection between overall satisfaction with organisational culture and the subsequent display of citizenship behaviours related to performance; performance defined as the quantity of output or quality of craftsmanship. Bateman & Organ (1983) propose that due to the manager being a representative of the organisational culture and values, workers equate organisational satisfaction with how management is treating them. Consequently, citizenship behaviours are often displayed for the benefit of the manager and as such, the managers’ attitude has a powerful effect on how the worker perceives and evaluates the organisational climate, impacting job satisfaction, absenteeism, and productivity (Bateman & Organ, 1983).

The organisational climate has a strong impact on teamworking communication (Bateman & Organ, 1983) and when the organisational climate is disturbed or stressed, communication barriers can emerge, leading to interpersonal conflict (Madhukar, 2010). This suggests that with external pressures on highway engineering projects unlikely to cease, the stressed organisational climate contributes to communication barriers and interpersonal conflicts within highway engineering teams. Fielding & du Plooy-Cilliers, (2014) highlight the need to have harmonious interpersonal communications, stating that for effective communication to take place, there must be ‘sharing of meaning created that is the same for all’ (Fielding & du Plooy-Cilliers, 2014, p.11).

In contrast, Hollnagel et al., (2005, p.15) argues that interpersonal conflicts are inevitable in teams because each team member holds different viewpoints based on their personal interpretation and perception, which is formed from their individual knowledge, experience, and expectations. This pragmatic explanation of interpersonal conflict explains why managers will likely have very different views and expectations from groundworkers. Davis’ (1997) hypothesis supports this, proposing that engineers are mainly concerned with safety and quality, while managers with costs and customer satisfaction. In practice, it is likely that engineers and managers share those concerns yet have separate agendas. However, differences in hierarchical positions can create psychological and cultural barriers (Madhukar, 2010).

2.4.1 Organisational culture and subcultures

As within most companies, the organisational hierarchical structures in highway engineering give rise to cultures and subcultures which emerge from shared rank or status (Wilson, 2001), such as groups of workers that share the same job-titles, responsibilities, level of education and training. Anderson (2012, p.299) proposes that management methods create unique site working cultures, and that within those site cultures, numerous subcultures must coexist on projects such as ground working crews or sub-contractor gangs.

Groundworkers and surfacing crews are known to create their own subculture and are commonly referred to as a ‘gang’ (Cohn, 2008). According to Gorse, Johnston & Pritchard (2012, p.179), the term ‘gang’ refers to ‘a group of skilled operatives who perform as a team’. The ‘gang’ may also been seen as ‘a gang of labourers’ separated from skilled, professional engineers, potentially creating a social status barrier to management and the wider company. And if groundworkers and sub-contractors need to develop subcultures, this suggests that they may not be treated or feel as if they have much in common with the project owners or managers. According to Anderson (2012, p.299) and Tutt et al., (2011), ‘crews and gangs’ who form subcultures can lead them to behave differently in terms of adhering to the sites established health and safety rules. Because gang foremen and supervisors share a similar employment history with the gangs they supervise, and have progressed from a trade background, they are better placed to positively influence their gangs’ safety behaviours because they are part of those subcultures (Hartley & Cheyne, 2012; Tutt et al., 2011). Therefore, managers who work at the ‘frontiers of different subcultures’ need to learn to interact with those subcultures and acknowledge good citizenship behaviours by groundworkers which could reduce barriers to communication, promote inclusion, improve perceptions of the organisational climate, and encourage health and safety adherence. (Kitchin & Kitchin, 2010, p.39)

Bateman & Organ, (1983) argue that the organisational culture should support a work climate that allows interpersonal conflict to be minimised within interdisciplinary teams to protect and conserve organisational resources. Although interpersonal conflict may be minimised by adjusting the working climate, it may be useful to expect subcultures to form and conflicts to occur, a point supported by Spaho (2013). Spaho claims that it is not possible to imagine organisational communication without conflict because people have different opinions, conflict is normal and therefore should be expected. To expand on this point, it may be necessary to encourage a working culture where the formation of subcultures and interdisciplinary teamworking conflicts are normal and expected, and ensure that there are working policies and procedures in place supporting the management of, and swift resolution of those clashes.

2.5 Working communication procedures

The objective of communication is to inform. Engineering staff need to be kept informed about the organisations objectives, strategies, policies and procedures, plans, systems, and project priorities (Madhukar, 2010, p.5), and communication is a process that must be managed by companies in an organised way, through their working policies and procedures (Medina, 1999). Working communication procedures within transportation highway engineering organisations use standard communication methods and operating procedures to share information in a clear and systematic way (HSE, 2017). The organisations working communication procedures underpins technical aspects of project delivery such as safety and productivity, as well as supporting effective interpersonal teamworking, working environment and project delivery. In this way, various methods and practices of working communication procedures supports every business function (Madhukar, 2010, p.10). Medina (1999) points out that although there can multiple methods of communication within organisations, working communication can be classified as verbal and non-verbal.

2.5.1 Verbal and non-verbal communication

2.5.1.1 Verbal communication

Transmitted though hearing and sight, verbal communication can be oral or written (Medina, 1999). In construction engineering settings, verbal communication is fundamental for addressing issues, problem solving and forming and maintaining collaborative working relationships between team members (Emmitt and Gorse, 2007). Verbal communication can be affected by environmental factors, such a speaking in a noisy environment, personal factors such as interpersonal issues, or cultural factors such as education level, and professional differences (Klimova & Semradova, 2012; Tsai, 2009), which implies that groundworkers could encounter such barriers when speaking with their managers. Miller (2014, p.31), states that communication barriers are also affected by the direction of communication.

Communication can flow in different directions. Downward communications flow from higher to lower levels of authority, such as from a manager to groundworker. The purpose of downward communication is primarily to give instructions, provide company policy information and feedback on performance which may take place in formal meetings, phone calls, emails and documents (Miller, 2014). Whereas horizontal communication flow is often between co-workers, its purpose is to share information, to collaborate, influence and coordinate working tasks, and can take place in a less formal way (Medina, 1999, p.126; Miller, 2014, p.31). Upward communication flow can be from lower to higher levels of authority, education, or experience, with the purpose of informing, to pass on information. This communication flow may not be supported by formal environments such as office meetings, however still requires a formal delivery method such as a professional face to face conversation, phone call or email (Medina, 1999, p.126; Tutt et al., 2011).

Miller (2014, p.31) states that most communication flows downwards, in the form of ‘orders, rules and directions’ from managers to employees with minimal feedback from lower level workers to higher level management and proposes this is caused by the effect of outdated classical management theories, and potentially create negative attitudes towards the organisations’ working communication procedures (Tutt et al., 2011).

With technological advancements, verbal communication incorporates wide ranging communication methods such as email, social media platforms, text messages, video conferencing, instant messaging, and forums. Klimova & Semradova (2012) warns that these communication technologies can cause language communication differences. This draws attention to the issue that some forms of verbal communication are not as clear as others, which could be because they do not allow for non-verbal communication and gestures to be seen and experienced, suggesting that non-verbal communication may be an essential factor in supporting effective verbal communication.

2.5.1.2 Non-verbal communication

Albert Mehrabians’ (1967) research of feelings and attitudes discovered that during heightened emotional situations only 7% of communication is verbal; the majority are non-verbal, facial and paralinguistic expressions (Mehrabian, & Ferris, 1967). This would mean that the often busy and noisy environments of site-based settings, coupled with engineers working under project pressures can create communication barriers, and impact the ground worker engineers’ communication with their team. Therefore, within challenging or stressful site working environments, to practice safely and effectively, the engineer would need to rely on making use of verbal and non-verbal communication skills.

Miller, (2014, p.32) points out that physical characteristics, such as body movement and posture, can communicate non-verbal working attitudes, and how workers are dressed also communicate non-verbally about aspects of their job status, beliefs and attitudes which can create or reduce barriers to communications. This is evident on highway engineering construction sites, where all workers wear safety clothing, although project owners, planners and site managers dress differently to highway engineering groundworkers to meet the demands of their job.

Facial expressions and gestures are independent of speech but can still have a direct verbal translation (Knapp, Hall, & Horgan, 2014, p.9). This is evident on large engineering projects, when groundworker engineers working on busy, noisy sites makes workers heavily reliant on a range of non-verbal gestures, as it is often difficult to hear and clearly see verbal instructions. To overcome this communication barrier, engineers wear highly visible safety clothing, and use a range of body language gestures to communicate non-verbally to other workers. Verbal and non-verbal communication can therefore support a range of working communication procedures and safety behaviours.

2.5.2 Functions of working communication procedures

‘To achieve success in health and safety management, there needs to be effective communication up, down and across the organisation.’ HSE (2017).

This statement by the Health and Safety Executive clearly outlines the importance of communication flow across all team members within an organisation. As working communication procedures are mostly in written form, suggests that this is the most used, reliable, and effective method of imparting information. Miller (2014, p.31) argue that health and safety rules and guidelines must be consistent and permanent, adding that relaying working procedures such as health and safety instructions via oral communication is unreliable, and not as effective as written communication as written communication is less likely to be misinterpreted and remains unchanged.

Millers argument seems supported by the vast amount of health and safety literature widely available for all team members in engineering and construction organisations. Due to risk implications, workers take these guidelines seriously and are routinely part of site induction processes and day-to-day working procedures. Regardless of the vast collection of written forms of health and safety guidelines, employee handbooks, safety rules and instructions, construction engineering continues to be one of the ‘most injury-prone industries’ (Sousa, Almeida & Dias 2014; Kines et al., 2010).

Kines et al., (2010) discovered that site based construction workers have an ‘informal and oral culture of risk’, where ‘safety is rarely openly expressed’. The study examined the effects of coaching site foremen to increase the efficacy of their verbal safety communications with their team, which increased site safety. It is worth noting that these improved safety effects were found to be long lasting. Improving communication standards supported safety behaviours incorporated into daily engineering practice, which increased occupational safety (Brauer,2016; Fielding & du Plooy-Cilliers, 2014).

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE, 2017) suggest, that to create a strong safety culture, a ‘genuine management to workforce partnership’ needs to develop, which should be based on ‘trust, respect and co-operation’ and that when established, health and safety issues can be solved in a collaborative way, where ‘ideas and solutions are freely shared and acted upon’. This they call ‘worker involvement’ and explain that this is more than just manger-to-worker consultation; and propose ways of ‘encouraging open communications’ such as ‘toolbox talks and health and safety walkabouts’ to encourage two-way communication between managers and workers.

The HSE (2017) suggestions of how to create health and safety adherence cultures depend on communication flowing horizontally, between team members, and upwards from worker to manager. It is important to acknowledge then that most written working communication procedures such as health and safety guidelines, are not created by the audience they cater for, because the defining and shaping of an organisations’ policies and procedures are decided within the business owners and senior managements planning processes (Anderson, 2012). Therefore, written instructions, delivered in a downwards communication flow, potentially create barriers to the majority of the audience they cater for, a point picked up by Tutt et al., (2011), who claim that this management to worker information flow stigmatises open discussions of health and safety issues on site, and clashes with ‘construction site culture.’

Wernebjer et al., (2012) propose that in large organisations, workers complained about ‘poor communication from managers,’ and managers complained about how employees ‘did not follow directives’, that ‘information was not being received’. This indicates that the size of the organisation may create barriers to communication, however Brauer, (2016, p.440) argues that whatever the size of the organisation, for workers to follow directives and make use of information relies on modern management methods that can support two-way communication; the giving and receiving of feedback, as workers ‘need to know if they perform tasks correctly and safely’ to prevent harmful results.

Pritchard (2015) proposes that out of date management methods are still used because engineers ‘lack people skills.’ This provocative viewpoint suggests that for modern working communication procedures and methods to emerge, engineers need to improve their people skills, to translate working procedures into practice. Although Pritchard makes a sweeping generalisation about engineers, this view of engineers lacking people skills and being unable to communicate effectively are not uncommon (Williams, 2004, p.72). As engineering practice takes place in such an intensely oral communication culture, skills such as ‘translation, clarity, negotiation, and listening are vital’ (Donnell, Aller, Alley & Kedrowicz (2011) and with frequent interpersonal and small group experiences being commonplace, an engineer needs to possess excellent interpersonal skills. Donnell et al., (2011) draw attention to an ongoing issue, ‘Disparity clearly exists between the communication skills taught to engineering students’ and industry expectations. This leads to the question, that if graduating engineers are underequipped for real-life working situations, what do engineers need to develop or strengthen their professional and interpersonal communication skills?

2.6 Communication skills and education

Communication is a skill and as such can be taught (Nylen & Pears, 2013).

The Institution of Engineering and Technology (2017) stress that it is no longer enough for engineers to have technical communication skills, claiming that ‘good interpersonal skills are essential to a successful engineering career.’ Ruf & Carter, (2009) claim that although students are taught formal communication methods, they lack the interpersonal skills needed to work in a team environment leading to employers being dissatisfied with engineering graduates’ communication skills. Dukhan & Ravess, (2014) argue that as society transitioned from the industrial age towards the information age, led to a ‘knowledge-based’ economy, which calls for a change to engineering curricula to focus on teaching communication skills to better prepare engineers for their professional lives. In response to this need, engineering associations and regulatory bodies such as the Institution of Civil Engineers member attributes (ICE, 2017), acknowledge the importance of developing interpersonal communication skills (Dukhan & Ravess, 2014). The Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, state that these skills can be taught and assessed as part of an active and cooperative learning environment (Shuman, Besterfield‐Sacre, & McGourty, 2005) which could address the ‘competency gap’ in engineers’ education (Sageev, & Romanowski, 2001).

Skills training needs to be incorporated into engineering curriculums because communication skills are central to ‘everyday functioning’ of the engineering profession, (Vampola et al., 2010), and engineers should be prepared to target their communication skills to different audiences. To be able to reflexively adjust their communication skills to suit various audience, such as presenting information to a manager, raising a safety concern with a supervisor or explaining something to a well-known co-worker, relies on the engineers’ interpersonal skills (Nylen & Pears, 2013). Teaching effective interpersonal communication skills increases motivation, enables collaborative teamworking, supports assertiveness skills development and managing conflict, and improves overall team performance (Donnell et al., 2011; Ellemers, De Gilder, & Haslam, 2004).

Engineers need to have strong, well developed communication skills to work effectively with interdisciplinary and globally diverse teams (The National Academy of Engineering, 2004). Professional communication skill development is therefore a vital part of the engineers’ career path, and yet multiple continuing professional development courses are aimed at developing leadership communication skills related to project management or senior management skills (Lester, 2014; Goleman, 2014). This is to be expected considering communication difficulties in teams are often directed towards the manager to support the resolution of conflict and communication difficulties. In this way, managers and senior managers are expected to become more effective communicators as their leadership role develops, and as such, organisations often support their further training in these areas. What is less clear however, is how groundworker engineers develop and improve their professional communication, interpersonal and teamworking skills.

With downward flow of information from managers to groundworkers being prone to communication barriers (Miller, 2014), there may be ways of improving upwards communication flow, to promote more equal, two-way communication methods by increasing communication skills education for groundworkers (Fielding & du Plooy-Cilliers, 2014). It therefore seems necessary to investigate the impact of information flow, from groundworker to managers. However, currently very little is known about the actual impact of working communication procedures on groundworkers.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study method

Investigating the effect of working communication procedures on transportation engineering staff and contractors, required collecting attitude variation response data from a range of highway engineers. As quantitative data can incorporate psychometric scales, this data collection method was chosen as it supports the statistical analysis of the attitudes or opinions of a group of people (McLeod, 2014).

3.1.1 Study design and distribution

The study design incorporated a Likert scale within a questionnaire. Likert items focused on working communication procedures to enable highway engineers’ strength of attitude to be numerically represented, quantified, and evaluated (Likert, 1932; McLeod, 2014).

The questionnaire consisted of: A cover page outlining the purpose of the study, participation information explaining confidentiality and a job position identification question (see Appendix B). The main questionnaire contained 9 statements representing a selection of working communication procedures that the participant was asked to evaluate using a 5 point Likert scale ranging from: 1. Strongly disagree, to 5. Strongly agree (see Appendix C).

3.1.1.1 Design considerations

Even though it is common for Likert research methodology to be criticised because of the assumption that data from Likert scales are ordinal and therefore parametric methods cannot be used (Sullivan & Artino, 2013), Norman (2010) argues that this is not the case as long as care is taken regarding the sample size and that the scale itself offers ‘a symmetry of categories’ around a midpoint. Norman highlights that issues seem to arise interpreting Likert scale data because of the difficulties measuring the strength of attitude in the space between the questions.

However, if items on the scale are designed to be combined into a single variable, then these combined variables (responses) can form a composite score when items on the composite scale are closely related (Clason & Dormody, 1994). This allows Likert scale data to be analysed and interpreted as interval data even when this data may not be normally distributed (Boone & Boone, 2012). Traylor, (1983) agrees that ‘questionnaires can be robust to violations of the equal distance assumption.’ Likert scales do therefore allow for degrees of attitude to be recorded and analysed, although interpretation of any discovered statistical significance may need to be approached with caution. These points emphasise the need for robust foundations to be established in the design of the questionnaire and scale, in order to maximise the power of parametric statistical tests.

For parametric statistical tests to be performed, the study was specifically designed to incorporate a series of statements that when combined, had the potential to measure a particular trait. Boone & Boone, (2012); De Winter, & Dodou, (2010) stress that descriptive statistics recommended for interval scales include; ‘mean scores for central tendency’ and ‘standard deviations for variability’. Further recommending that deeper data analysis include ANOVA, t-test and Pearson’s r test. Because of these considerations, it was decided to ensure that all questions related directly to working communication procedures, in an attempt to reduce distortion and increase the stability of the study (Sullivan & Artino, 2013).

Sullivan & Artino (2013) stress that the sample size needs to be ‘adequate’ ‘at least 5-10 observations per group’ to support parametric test power. Evans & Rooney, (2014) support this point adding that when it comes to analysing Likert questionnaires, the t test and ANOVA test have similar power and are able to provide ‘protection against false negatives.’

The main design concern therefore, was to be aware where weakness in statistical power may reside, and so to address this, further steps were taken:

The self-administered questionnaire was designed to:

- To support a random sampling method: Hampshire County Council Highways Depots distributed questionnaires to highway engineers via central office administrators over a two-month period. Completed questionnaires placed in sealed envelopes were collected and collated by the researcher on 10th March 2017.

- Reduce sample bias: As highway maintenance and surfacing teams were particularly busy over the winter period, questionnaire distribution took place over an extended time period from January to March 2017 to ensure these workers had the opportunity to participate.

- Reduce social desirability bias: By offering anonymity where no identifiable data was requested; providing a choice of both completing and returning the anonymised questionnaire, for example, in a plain sealed envelope to a box in reception.

- Increase accessibility to questionnaire: By making the questionnaire available in different formats; hard copy and offering an online Survey Monkey version, meant participants could complete the questionnaire to fit in with work commitments.

- Increase participation and reduce survey fatigue: The questionnaire was designed to be completed in less than 2 minutes, standing up if necessary, to accommodate busy working environments.

- Increase the sample size: As a small effect size was expected (McLeod, 2014).

- Transparency: Measurement of highway engineers’ attitudes were direct, they were aware they were being studied, however were also offered anonymity.

3.1.1.2 Independent and dependant variables

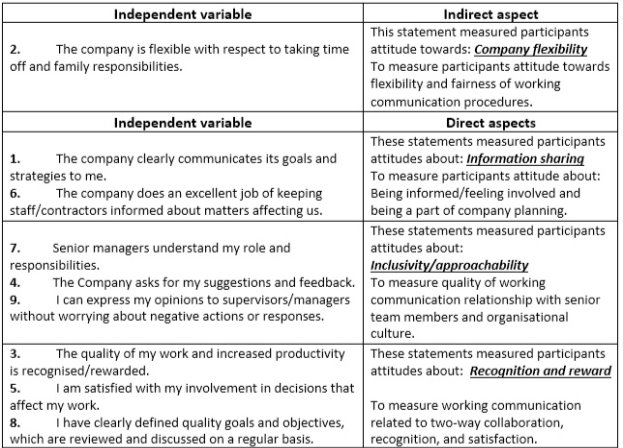

The challenge was to try and collect wide ranging attitudes about the effect of certain features of working communication procedures, from engineers with different job descriptions. Therefore, 9 independent variables (questionnaire statements see Table 1) were designed to measure engineers’ attitudes towards working communication procedures (indirect aspects) and the effects of the company’s’ working communication procedures on engineers’ attitude (direct aspects).

Table 1. Questionnaire statements grouped by variables.

| Working Communication Procedure Statements | |

| Independent variable | Indirect aspect |

| 2. The company is flexible with respect to taking time off and family responsibilities. | This statement measured participants attitude towards: Company flexibility

To measure participants attitude towards flexibility and fairness of working communication procedures. |

| Independent variable | Direct aspects |

| 1. The company clearly communicates its goals and strategies to me.

6. The company does an excellent job of keeping staff/contractors informed about matters affecting us. |

These statements measured participants

attitudes about: Information sharing To measure participants attitude about: Being informed/feeling involved and being a part of company planning. |

| 7. Senior managers understand my role and responsibilities.

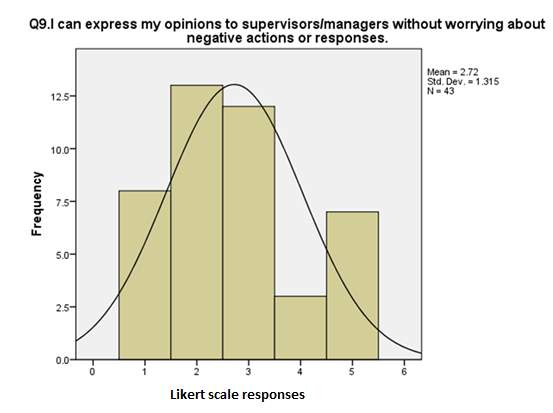

4. The Company asks for my suggestions and feedback. 9. I can express my opinions to supervisors/managers without worrying about negative actions or responses. |

These statements measured participants attitudes about: Inclusivity/approachability

To measure quality of working communication relationship with senior team members and organisational culture. |

| 3. The quality of my work and increased productivity is recognised/rewarded.

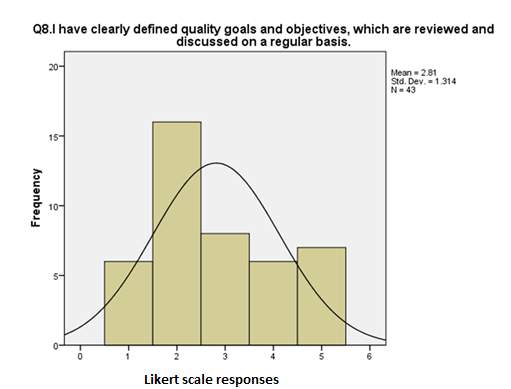

5. I am satisfied with my involvement in decisions that affect my work. 8. I have clearly defined quality goals and objectives, which are reviewed and discussed on a regular basis. |

These statements measured participants attitudes about: Recognition and reward

To measure working communication related to two-way collaboration, recognition, and satisfaction. |

Table 1.

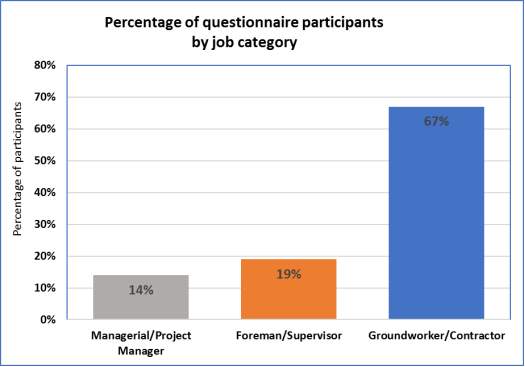

Due to the anticipated effect size, the original dependant variable design was altered to support parametric test power (Sullivan & Artino, 2013). As the study was comparing more than one group meant a null hypothesis was set (Kim, 2015). To test the existence of a null hypothesis linking job position with working communication procedures, the original job characteristics category group (see Figure 2) captured data were further rearranged into two groups; ‘managers/supervisors’ and ‘groundworkers/contractors’. It was also altered to simplify the analysis between job position and strength of attitudes.

3.1.2 Questionnaire participants

Of the 43 questionnaire participants from Hampshire County Council Highways Departments, 28 participants responded using the paper version and 15 by online survey.

Participants consisted of:

- 6 Managers/Project Managers,

- 8 Foreman/Supervisors

- 29 Gang/Crew members/Groundworker operatives

The cover page of the questionnaire (see Appendix B), invited participants to identify their job position, (see Figure 2), rather than their employment status, to encourage all highway engineers, both staff and contractors to participate.

Figure 2: Question 1 from Appendix B

Groundworker respondents were likely to include contractors, with manager respondents more likely to be employees of Hampshire County Council (HCC). This is because, according to HCC’s treasury report, (Hampshire County Council, 2016), HCC employs over 37,000 staff and over the last 3 years, the numbers of employees within ‘Economy, Transport and Environment’ sector has declined. Table 2 shows this downward trend and yet the use of groundworker contractors has risen steadily over this time (HCC, 2017).

Table 2. Hampshire County Council Employees

| Employees within ‘Economy, Transport and Environment’ departments at HCC (2014-2016) | |

| Financial Year to March | Employed staff |

| 2014 | 739 |

| 2015 | 603 |

| 2016 | 588 |

Table 2. Adapted from Hampshire County Council, (2016).

3.1.2.1 Hampshire County Council Highways: Areas covered

Hampshire County Council employs over 37,000 staff, with 588 staff employed within the Transport, Economy and Environment sectors which include administrative and finance staff (Hantsweb, 2015; Hampshire County Council, 2016). Hampshire County Council Highways Department also hire contractors to support highway maintenance work. Amey has been the main contractor that partnered with Hampshire County Council over the last 5 years, however Skanska has recently won a 7-year contract due to start August 2017 (HCC, 2017).

Hampshire County Councils’ highway maintenance teams work across five highway maintenance depots that provide routine and emergency maintenance of Hampshire’s 5,300 miles of roads and footpaths outside Southampton and Portsmouth. This excludes trunk roads and motorways which are maintained by the National Highways Agency (Hantsweb, 2015; Hampshire County Council, 2016). Hampshire is one of the largest counties by land area, covering approximately 1,400 square miles Hampshire County Council is responsible for the public services across all 11 district and borough councils highlighted in the map below (see Figure 3).

Hampshire County Councils’ highway maintenance teams work across five highway maintenance depots that provide routine and emergency maintenance of Hampshire’s 5,300 miles of roads and footpaths outside Southampton and Portsmouth. This excludes trunk roads and motorways which are maintained by the National Highways Agency (Hantsweb, 2015; Hampshire County Council, 2016). Hampshire is one of the largest counties by land area, covering approximately 1,400 square miles Hampshire County Council is responsible for the public services across all 11 district and borough councils highlighted in the map below (see Figure 3).

Figure3: Adapted from Hampshire County Council (2014).

4. Results

4.1 Strength of attitude towards working communication questionnaire statements for all participants

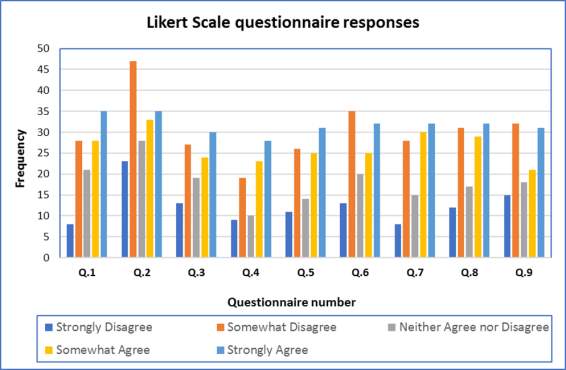

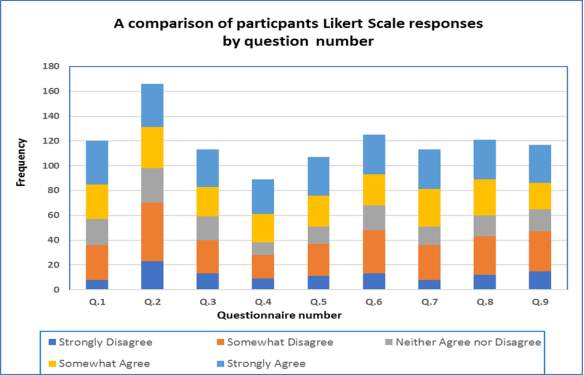

Figure 4

Figure 5

The questionnaire study results contained no missing data, participants maximum individual score = > 45, as 9 Likert scale items were allocated a number from 1 to 5. (The questionnaire statement list, Likert scale questions and a complete list of how each individual responded to the questionnaire can be found in Appendix D).

Table 3. Frequency of results. N = 43.

Table 3. Frequency of results. N = 43.

| Likert Scale | Q.1 | Q.2 | Q.3 | Q.4 | Q.5 | Q.6 | Q.7 | Q.8 | Q.9 | Scale total |

| 1. Strongly Disagree | 8 | 23 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 8 | 12 | 15 | 112 |

| 2. Somewhat Disagree | 28 | 47 | 27 | 19 | 26 | 35 | 28 | 31 | 32 | 273 |

| 3. Neither Agree nor Disagree | 21 | 28 | 19 | 10 | 14 | 20 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 162 |

| 4. Somewhat Agree | 28 | 33 | 24 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 29 | 21 | 238 |

| 5. Strongly Agree | 35 | 35 | 30 | 28 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 286 |

| Total per question | 120 | 166 | 113 | 89 | 107 | 125 | 113 | 121 | 117 |

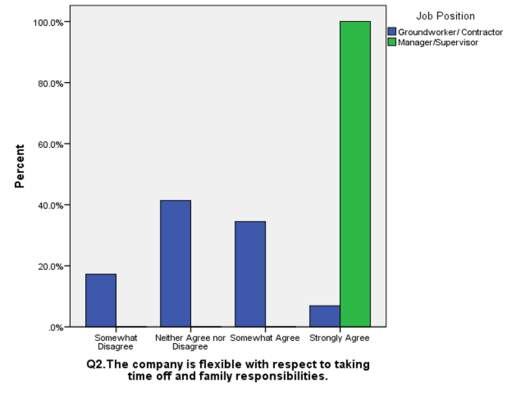

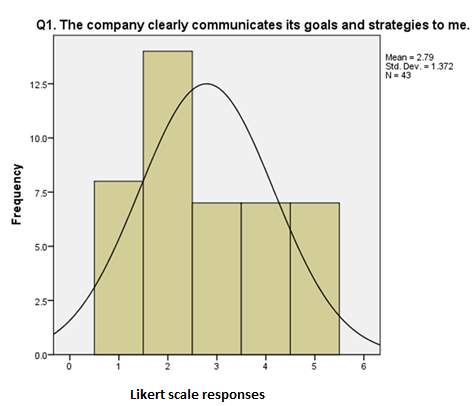

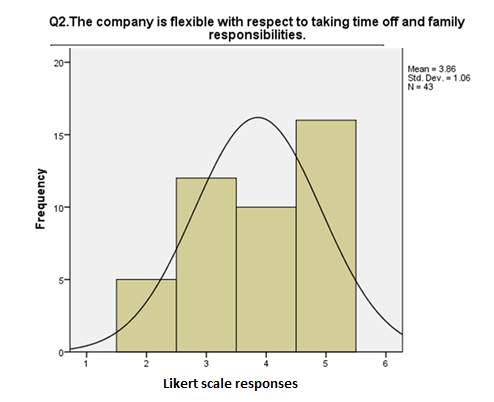

A visual inspection of the initial results in Table 3 suggested that there seemed to be noticeable variations (see Figure 4 & 5), in responses and strength of attitude especially for Q.2, which shows higher levels of agreement, across all participants. Q.2 was the only independent variable with an indirect aspect statement (see Table 1), which measured attitudes towards company flexibility and fairness.

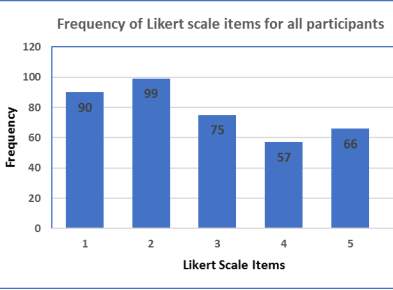

Figure 6

Figure 6 represents the Likert item frequency for all participants. The most frequent response n = 99 from participants was ‘Somewhat Disagree’ and ‘Strongly disagree’ n = 90, with the least frequent response n = 57 ‘Somewhat agree’, and n = 66 ‘Strongly agree’. This gives the initial impression that all participants hold a more negative attitude towards working communication procedures, however this method of data analysis may provide a distorted viewpoint. To test this, further investigations of attitude was performed by; analysis of central tendency and variability by job category.

4.2 Strength of attitude towards working communication questionnaire statements by job category: Managerial, Supervisor and Groundworker

Figure 7

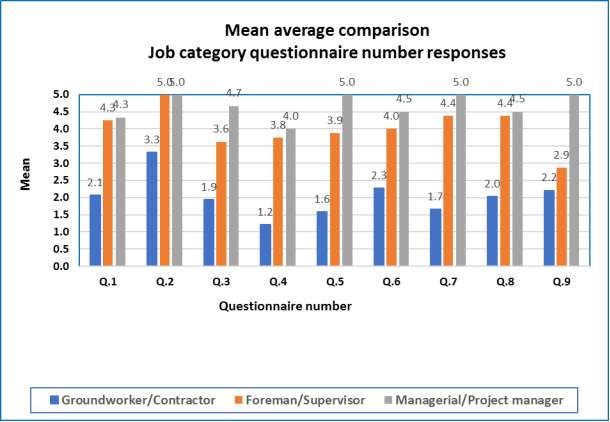

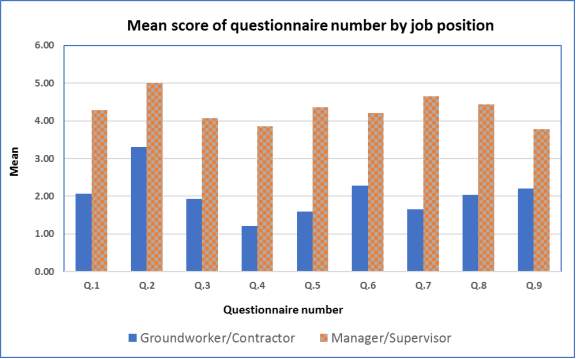

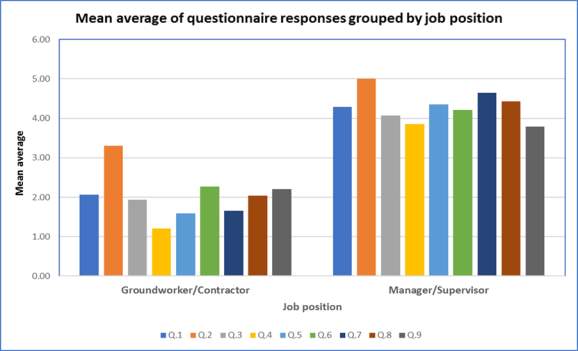

Questionnaire responses by job category, (Figure 7) provides visual representation of how job category sample sizes are unevenly distributed. Figure 8 shows the mean Likert scale ratings given by participants for each of the 9 questionnaire statements. Likert scale ratings were higher when answering Q.2, the indirect aspect statement of working communication procedures (see Table 1) compared to the direct aspects for all job categories.

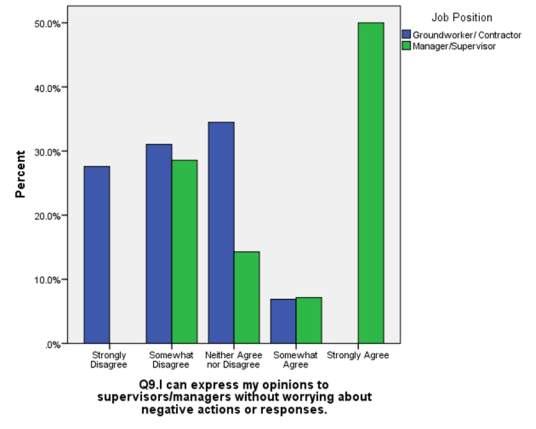

Differences in ratings between job categories were also visible, when looking at Q.4 (see Figure 8), ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ result M = 1.2, ‘Foreman/Supervisor’ result M = 3.8, and ‘Managerial/Project Manager’ result M = 4.0. These results indicate that working communication procedures affect attitudes depending on job category. This pattern is also evident in Figure 9, where working communication procedures has a far greater negative impact on ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ collective attitudes than ‘Foreman/Supervisors’, and the ‘Managerial/Project Managers’ category who reported the strongest positive attitude towards working communication procedures. Q.9 responses highlight this observation, where Managers responses M = 5.0 being noticeably separate from the rest of the team, ‘Foreman/Supervisors’ M = 2.9 and ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ M = 2.2.

Figure 8

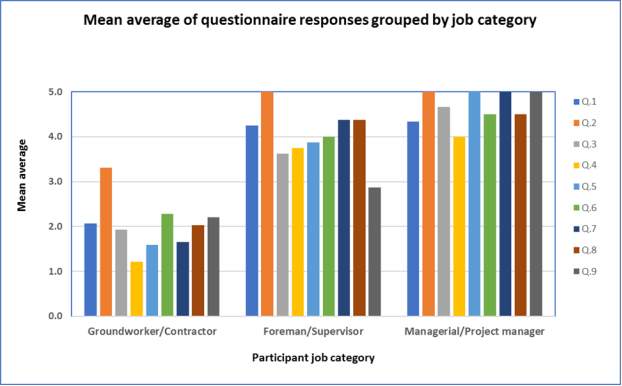

Figure 9

With sample size proportions being unevenly distributed, (see Figure 7), alterations to the study protected against the dilution of parametric test power. This was achieved by allowing an increase in sample size through the combining of the ‘Managerial/Project Manager’ group with the ‘Foreman/Supervisor’ group (Sullivan & Artino, 2013). (See Figure 10).

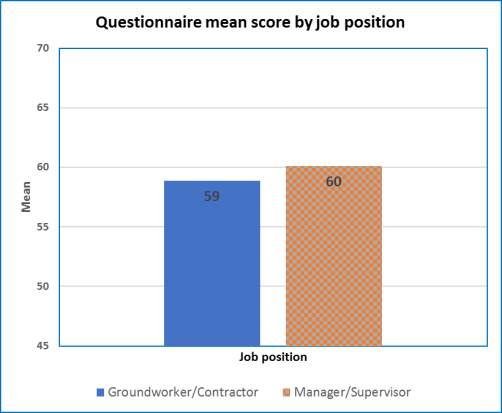

4.3 Strength of attitude towards working communication questionnaire statements by job position: Managerial/Supervisor & Groundworker/Contractor

Figure 10

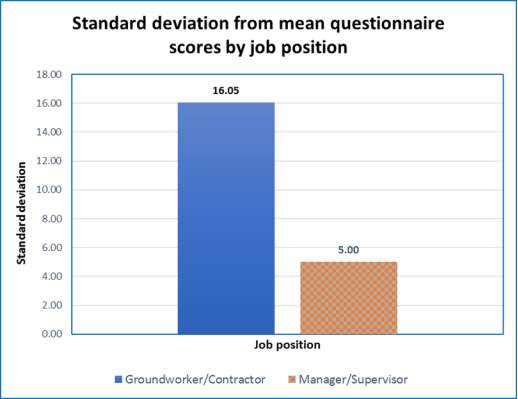

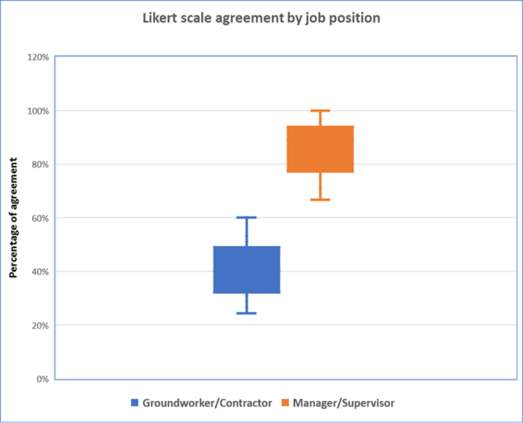

Figure 10 shows the questionnaire mean score by 2 job positions, ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ M = 59,and ‘Manager/Supervisor’ M = 60. These results indicate that these two groups may have offered very similar answers overall to the questionnaire. However, Figure 11 bar graph data representation challenges this, expanding on the explanation of mean data to show that ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ SD = 16.05,and ‘Manager/Supervisor’ SD = 5.00. With a difference of SD = 11.05, clearly demonstrates that the ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ group are much further away from central mean values than ‘Managers/Supervisors’. Figure 11 and 12, also highlight which direction ‘Groundworker/Contractors’ have deviated from the mean, showing significantly more disagreement than agreement, indicating that ‘Groundworkers/Contractors’ do not hold similar attitudes to ‘Managers/Supervisors’ regarding working communication procedures. (See Appendix E for full list of graphs representing questionnaire statements by job position and Appendix F for questionnaire statement responses displayed as histograms).

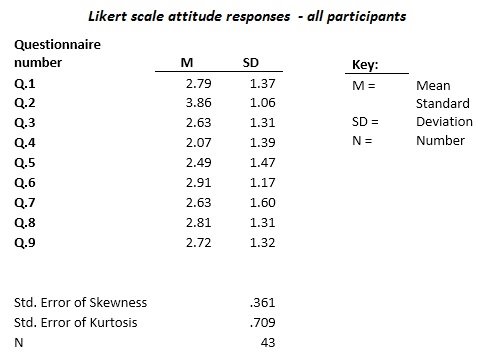

Figure 11

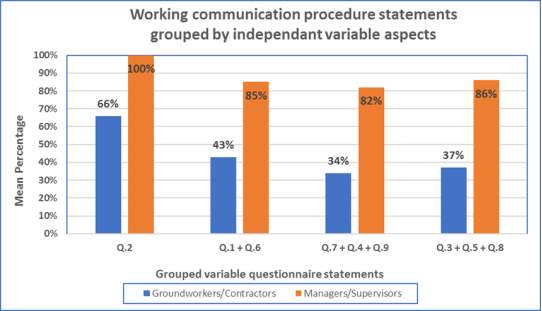

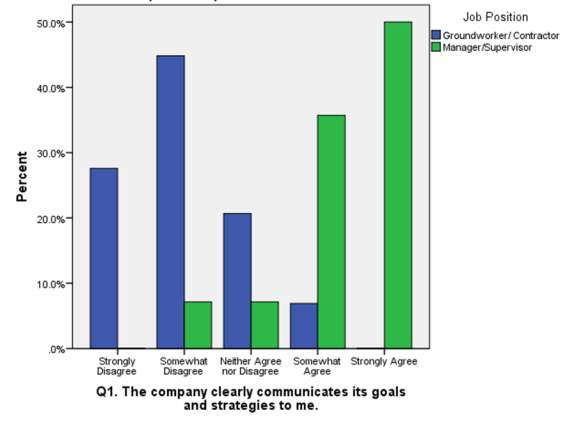

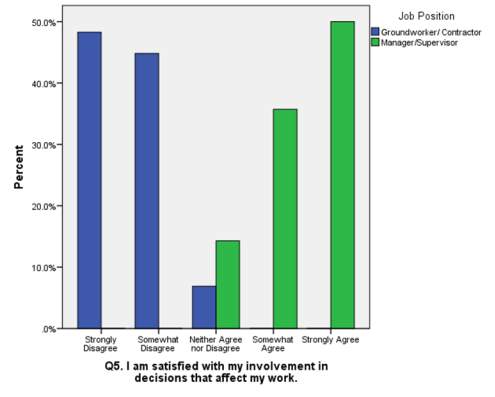

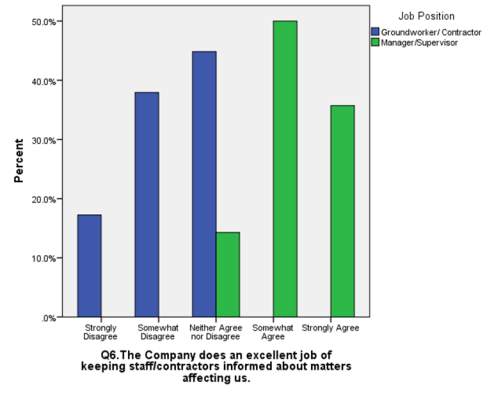

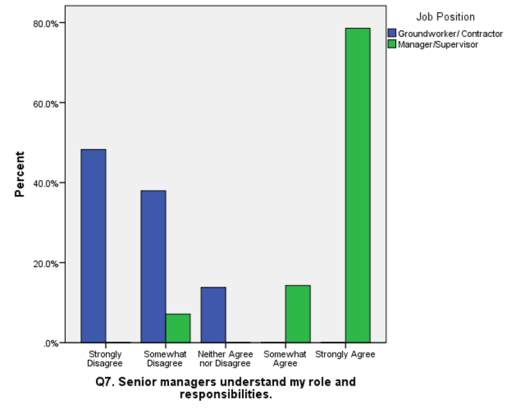

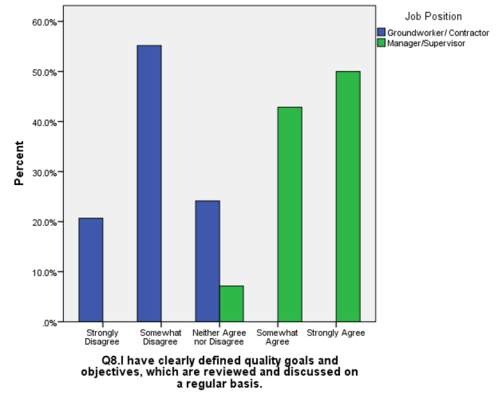

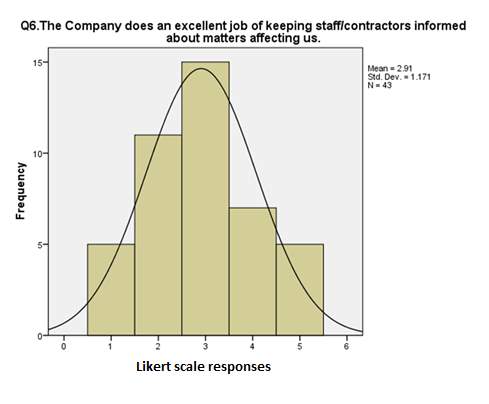

Table 4 highlights the mean and standard deviation results for each questionnaire number and it was noted that again, the indirect working communication procedure statement, Q.2 had the highest agreement level, M = 3.86 with the least deviation SD = 1.06 which may suggest that participants with different job positions may share similar attitude towards flexibility and fairness of working communication procedures (see Figures 12, 13).

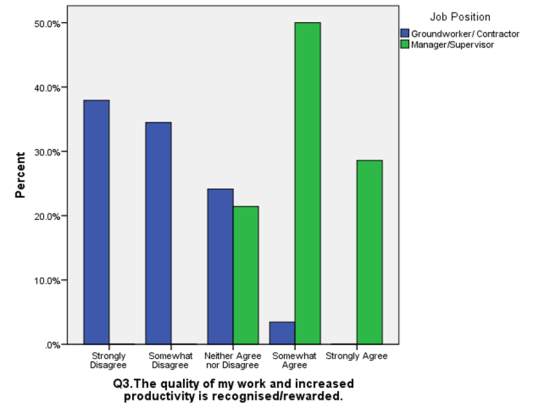

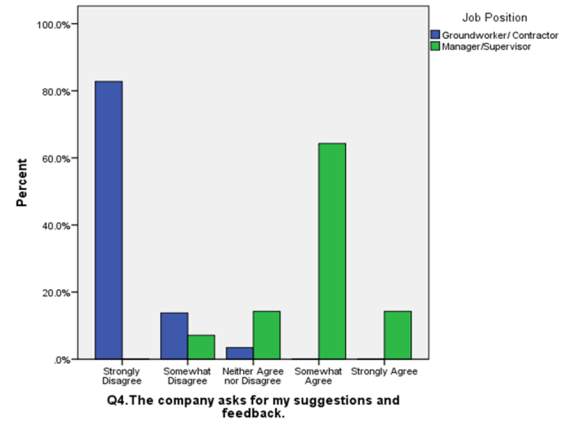

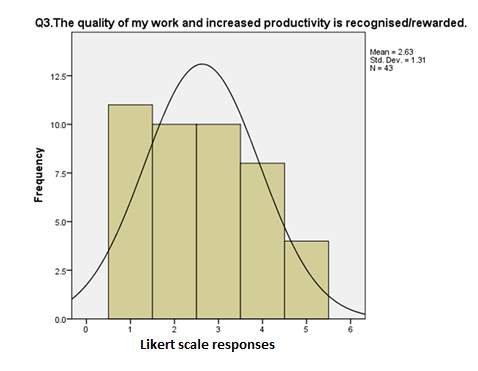

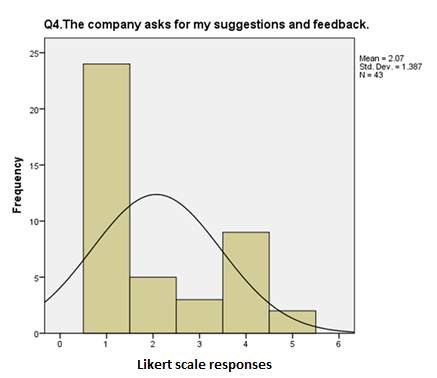

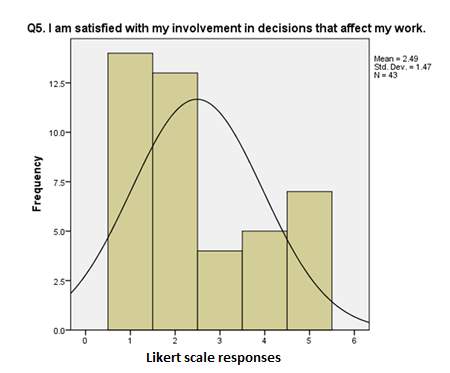

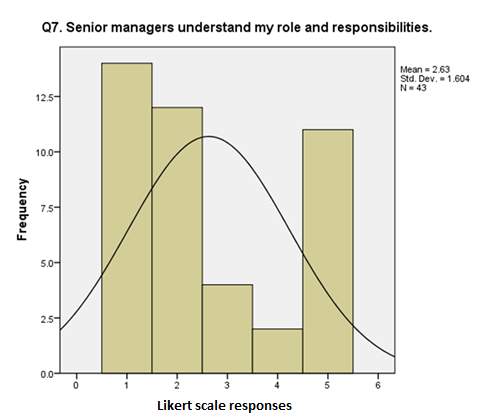

In contrast, a direct working communication procedure statement, Q.4. had the lowest agreement level M = 2.07 with a moderate deviation level SD = 1.39 which may suggest participants had less similar attitudes towards the company seeking their feedback. Q.7 also focusing on measuring inclusivity and working communication relationship with senior team members, showed that although overall answers clustered around an average mean value, M = 2.63, the SD = 1.60, may indicate that this question lead to the least shared attitude response between participants. Skewness .361 and kurtosis .709 were within normal range (< -2 to > +2) (IBM Corp, (2013). Indicating that the sample from this study was within normal distribution ranges.

Table 4.Likert scale attitude responses.N = 43

Table4.Created from SPSS v.22.0 (IBM Corp,2013).

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

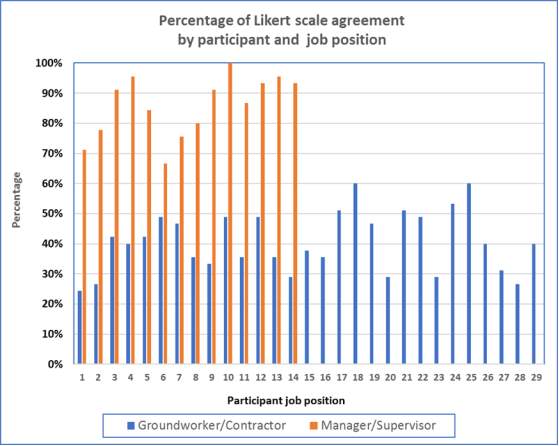

Figure 13 shows the mean average of Likert scale agreement by job position, separated clustered bar charts which supports the emerging pattern that ‘Groundworkers/Contractors’ do not hold similar attitudes to ‘Managers/Supervisors’ regarding working communication procedures. Figure 14 shows the percentage of Likert scale agreement clustered into boxplots for 2 job positions.

The same information has been presented in a different format in Figure 15. This bar chart shows all participants individual responses and strength of attitude. What is important to note is the lowest ‘Manager/Supervisor’ score of 67% was greater than the highest ‘Groundworker/Contractor’ score of 60%. The largest difference observed between job positions was a 76% difference in attitude to working communication procedures.

Figure 15

By comparing 2 job positions opposed to 3 job categories attitudes, results are noticeably further apart and this data offers some interesting insights into the possible strength of attitude differences between these 2 groups. Deeper data analysis was required to:

- Test mean differences between 3 job categories

- Test mean differences between 2 job positions

- Compare results and test the null hypothesis

Table 5. Working Communication Procedure Statements – Independent variable aspects.

Table 5. Working Communication Procedure Statements – Independent variable aspects.

Figure 15 shows results from grouped variable questionnaire statements in Table 5. Questionnaire statements resulted in differences in attitude, based on job position.

- Q.2: Company flexibility showed a 34% variation in attitude (lowest variation in results).

- Q.1 + Q.6: Information sharing = 42% variation.

- Q.7 + Q.4 + Q.9: Inclusivity/Approachability = 48% variation.

- Q.3 + Q.5 + Q.8: Recognition/Reward = 49% variation (highest variation in results).

Figure 15

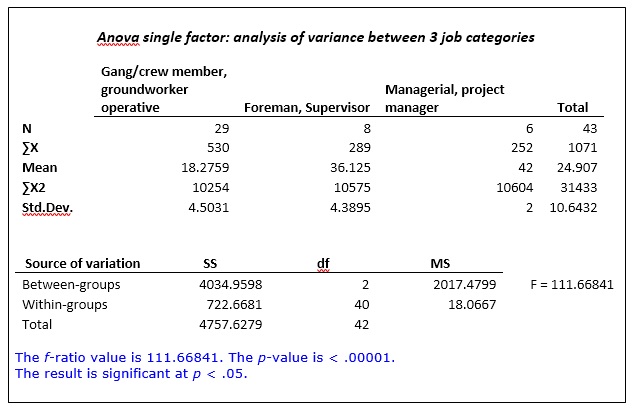

Table 6. One-way independent ANOVA test results: 3 Job Categories

Table 6. One-way independent ANOVA test results: 3 Job Categories

Table 7. One-way ANOVA test results: 2 Job Positions

Table 7. One-way ANOVA test results: 2 Job Positions

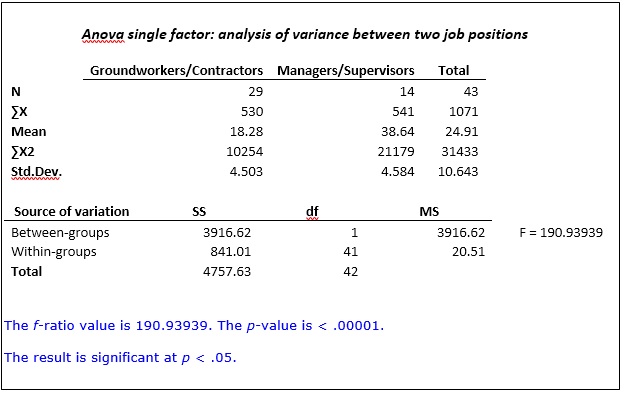

An ANOVA test was firstly performed to test the mean differences between 3 job categories (see Table 6) and then to test mean differences between 2 job positions (see Table 7). In both tests the p-value was significant at p < .05. The observed p value <.00001 suggested that there was strength of evidence against H0 where the null hypothesis should be rejected. The ANOVA tests demonstrated that statistically significant differences exist between group attitudes to working communication procedures.

- Table 6: 3 job categories F value results: F = 111.66

- Table 7: 2 job positions F value results: F = 190.94

According to Winter (2011) and Dorey (2010), the larger F value represents a stronger correlation between group variance that is more statistically reliable. For this reason reliance on using 2 job positions was continued.

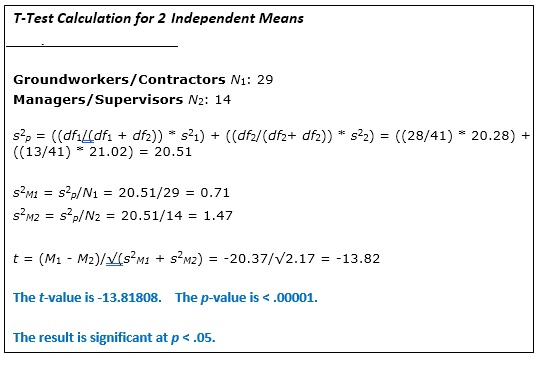

Table 8. T-Test results: 2 Job Positions

Table 8. T-Test results: 2 Job Positions

Table 8 shows that the same results can be drawn from the independent t-test as the one-way independent ANOVA test (Winter, 2011). The study firstly needed to also investigate and test the correlation between job position and working communication procedures. The study then needed to test the strength of possible linear relationship or association between job position and working communication procedures. Evans & Rooney (2014) state that the Pearson’s r test could discover if these variables were ‘systematically related’.

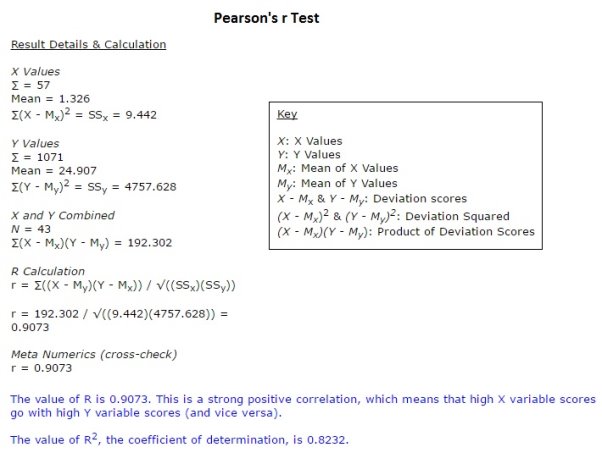

To run this Pearson’s r test X value scores were allocated in this way:

- Groundworkers/Contractors = 1

- Managers/Supervisors = 2

Y value scores = sum of Likert scale responses for each participant. Results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Pearson’s correlation coefficient results: 2 Job Positions

Value r = 1 would show a perfect positive correlation, (Evans & Rooney, 2014) therefore the result r = 0.91 from Table 7 demonstrates that this test suggests the existence of a very strong correlation between X (job position) and Y, (Likert scale agreement) results.

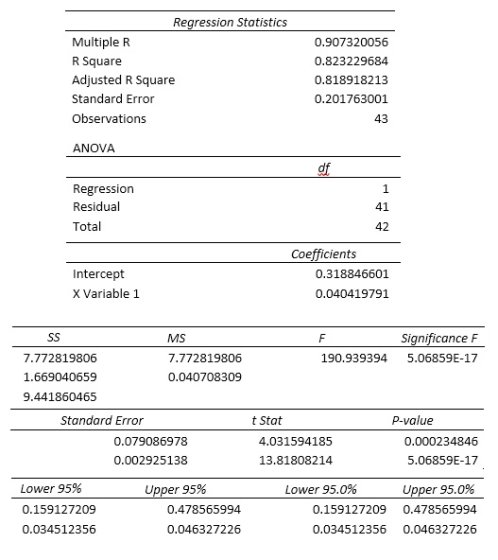

A regression analysis was performed to further examine the relationship between X and Y (see Table 10). However, at this test, results arrived at a data saturation point where no new themes seemed to be emerging (Taneja, 2009; McLeod, 2014).

To run this Regression Statistics Test, X value scores were allocated in this way:

- Groundworkers/Contractors = 1

- Managers/Supervisors = 2

Y value scores = sum of Likert scale responses for each participant. Results are shown in Table 10. The R square result seems to indicate the data closely fits the regression line.

Table 10. Regression statistics results: 2 Job Positions

Table 10. Regression statistics results: 2 Job Positions

CI = 95%

5. Discussion

5.1 Study results observations

The challenge of the study was to measure the effects of working communication procedures on engineers’ attitudes. The literature review revealed that some aspects of working communication variables had the potential to impact engineers working attitudes. The questionnaire statement design supported the study to examine these aspects of working communication procedures (See Table 1 and Figure 16).

Questionnaire statement (Q.2) was designed to measure participants attitude towards flexibility and fairness of the organisations procedures related to taking time off and family responsibilities. This was important to gauge participants’ overall relationship attitude towards the company, and as such, this question was separated from the rest, identified as measuring an ‘indirect aspect’ of working communication procedures.

The results to this question produced the highest combined job position agreement score of 83%. Although groundworkers results showed positive attitude towards the company, this was still 34% less agreement to the statement compared to managers.

As the objective of working communication procedures are to inform engineering staff about the organisations objectives, strategies, policies, and procedures, (Madhukar, 2010; Medina, 1999), questionnaire statements (Q.1 & Q.6), were designed to measure participants attitude about information sharing procedures, in other words, the downward communication flow (Miller, 2014). This was to gauge if participants felt well informed and involved in company planning. With a 43% variation of attitude between groundworkers and manager positions, groundworkers showed much higher levels of disagreement to these statements, and as such, it would be easy to infer that results suggest an issue with downward communication flow; where the company or manager needs to improve their delivery of information to improve team attitudes. Although this may be the case, how groundworkers receive that information may be affected by communication barriers, such as sub-cultural differences and attitudes hindering groundworkers ability to receive that information (Barnlund, 1970).

Another aspect of working communication measured was inclusivity and approachability where questionnaire statements (Q.7, 4 & 9) were designed to gauge attitudes towards organisational culture and relationships with senior team members. Groundworkers levels of agreement were significantly (48%) lower than managers/supervisors. Brumm & Drury, (2013) warn that workers negative attitudes towards inclusivity can lead to poor follower behaviours which can be harmful to productivity and project delivery. Although it may be tempting to take the stance that, this is a problem that needs to be fixed by management, this issue exists despite the vast amount of readily available resources, training, and information to improve leadership and management communication. This leads to the observation that these communication issues cannot be solved. However, there may be an opportunity for improvement by using a different methodology; where followers (workers) take a proactive stance, to make themselves included by actively seeking out that information, and invite discussions with leaders to encourage and inspire leaders to change course (Hackman & Johnson, 2013).

This type of two-way communication would likely depend on how approachable the leader or organisation is, and how prepared they are to listen. To support this two-way communication, leaders need to be open to receiving feedback in a non-defensive way that ‘invites creative challenge’ (Chaleff, 2009). Management methodology can strongly influence site working cultures (Anderson, 2012) and improve attitudes to approachability. Q.9 results (see Figure 8 & 9) raised attention to how engineers job categories connected with their attitudes to the leaders approachability. Supervisors and ground operatives attitude scores showed they were twice as likely to expect negative consequences when expressing opinions to their leader compared to managers’ attitudes.

Because feeling a valued part of the organisation supports long-term motivation and good teamworking attitudes (Herzberg et al., 2011), the final aspect of working communication measured was recognition and reward. Questionnaire statements (Q.3, 5 & 8) were designed to gauge attitudes towards collaboration, recognition, and satisfaction. Again, groundworkers levels of agreement were (49%) lower than managers/supervisors.