Alcoholism and Drug Dependence in Ireland: Study of Construction Workers

Info: 26955 words (108 pages) Dissertation

Published: 25th Nov 2021

Abstract

The impact of alcoholism and drug dependence in the workplace often focuses on premature death/fatal accidents; injuries/accident rates; absenteeism and loss of production. This can have a detrimental effect on construction sites. Many industry professionals suggest that substance abuse is prevalent on Irish construction sites from their experiences in the field. However, some believe it is a thing of the past and it is not a problem at present. Therefore, the purpose of this thesis is to to investigate and examine substance abuse and its presence in the Irish Construction Industry. This will be established through research and analysis of feedback from larger contractors and training services in the form of primary data.

The literature review provides a background to the thesis topic in the form of secondary research. This chapter covers all of the following areas that were applicable to the aim and objectives. This information was gathered through various books, publications, databases, academic journals and internet websites. Whilst the information is relevant to the thesis topic, it lacks statistics and specific information regarding the Irish construction industry itself. Hence, a number of interviews with industry professionals in Ireland were carried out in order to achieve this.

Five interviews as well as a focus group (3 members) were carried out within different companies in the Irish construction industry. The representatives were from two large Irish contractors (anonymous) as well as Salus training services. The data obtained from these interviews was used to validate and make comparisons between the literature review and the professional opinions

This thesis concludes on whether or not substance abuse is prevalent on construction sites in Ireland and reasons behind the verdict from both the primary and secondary research methods.

Abbreviations

SHWWA – Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005

HAS – Health and Safety Authority

WHO – World Health Organisation

NACDA – National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol

EMCDDA – European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development

EU – European Union

AADAC – Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission

UK – United Kingdom

USA – United States of America

UCATT – Union of Construction Allied Trades and Technicians

ILO – International Labour Organisation

BAC – Blood Alcohol Content

GHB – Gamma Hydroxybutyric

PCP – Phencyclidine

MDMA – Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

IOM – Institute of Medicine

OR – Odds Ratio

CIF – Construction Industry Federation

EAP – Employee Assistance Programme

CSAT – Center for Substance Abuse Treatment

MAST – Michigan Alcoholism Screening

AUDIT – Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

FORS – Fleet Operator Recognition Scheme

HSEQ – Health, Safety, Environmental and Quality

Table of Contents

Click to expand Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Aim and Objectives

Aim:

Objectives:

1.3 Thesis Summary

1.3.1 Chapter 1 – Introduction

1.3.2 Chapter 2 – Literature Review

1.3.3 Chapter 3 – Methodology

1.3.4 Chapter 4 – Analysis of Data and Findings

1.3.5 Chapter 5 – Conclusion and Recommendations

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Definition of Substance Abuse

2.2.1 Drug

2.2.2 Drug Use

2.2.3 Drug Misuse

2.2.4 Abuse

2.3 Substance Abuse in Ireland

2.3.1 NACDA Survey of Drug Prevalence in Ireland 2014/15

2.3.2 Alcohol Consumption in Ireland

2.3.3 Prevalence of Substance Use in the Construction Industry

2.3.4 Forms of Substances and their effects

2.4 Substance Abuse Related Workplace Accidents

2.4.1 Reviews on Relationship between Substance Abuse and Misuse and Occupational Injuries

2.4.2 Alcohol Use and Occupational Injuries

2.4.3 Drug Use and Occupational Injuries

2.5 Employer’s and Employee’s duties in relation to drug use in Ireland

2.5.1 Employer’s and Employee’s duties

2.5.2 Disciplinary Procedure

2.6 Remedies and Actions of preventing Substance Abuse in the workplace

2.6.1 Treatment Recommendations

2.6.2 Workplace Policies and Drug Testing

2.6.3 Employee Assistance Programmes (EAP)

2.6.4 Health Plans

2.6.5 Workplace Health and Wellness Programmes

2.6.6 Treatment

2.6.7 Screening and Assessment

2.7 Case Study

2.7.1 ‘Spotlight On’ Scheme

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.1.1 Aim of research

3.1.2 Research objectives

3.2 Research Strategy

3.3 Primary Research

3.2.1 Research design

3.2.2 Ethical considerations

3.2.3 Sample Frame

3.2.4 Sample size and Sampling strategies

3.4 Secondary Research

3.5 Interviewees:

Interviewee 1

Interviewee 2

Interviewee 3

Interviewee 4

Interviewee 5

3.5.1 Access

3.5.2 The Settings

3.6 Data collection

3.6.1 Procedure

3.6.2 Pilot study

3.6.3 Reflection on study process

3.7 Data analysis

Chapter 4: Analysis of Data and Findings

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Qualitative Findings

4.2.1 Past and Present

4.2.2 Suspicions of Substance Abuse on Site and Resulting Accidents

4.2.3 Link between accidents and alcohol/illicit drugs

4.2.4 Flaws in Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005

4.2.5 Lack of drug testing conditions in contracts

4.2.6 Substance use course of action

4.2.7 Workplace policies

4.2.8 Future Problems

4.2.9 Introduction of random drug testing in Ireland

4.3 Analysis

4.3.1 Prevalence of alcohol and drug use in the construction industry

4.3.2 Substance abuse-related workplace accidents

4.3.3 Employer and Employees duties regarding alcohol and illicit drug use in construction

4.3.4 Remedies and actions that may combat substance abuse

Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1 Aim and Objectives

5.1.1 Aim of research

5.1.2 Research Objectives

5.2 Achievement of aim and objectives

5.3 Limitations during the Research

5.4 Recommendations

References

Interview Questions

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction

“Research has shown that groups of people who work together, whether in small teams or larger organizations, develop shared beliefs and practices that can influence alcohol use” (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2011).

In many occupations, this workplace culture can influence various beliefs including acceptable drinking contexts i.e. routine drinking with co-workers before, during and after work as well as their drinking behaviour i.e. the number of drinks they consume, showing the effects of alcohol, partaking in fights, arguing with their supervisors, sleeping on the job, coming into work hungover (Ames, Grube, & Moore, 1997) or in the construction world, operating plant such as excavators or tower cranes while under the influence.

As well as the alcohol drinking issue in the workplace, there are some concern with a new culture of personnel who have a desire or habit of using illicit drugs and over using prescribed medications. Management are confronted with the acknowledgement that the workforce on the site are affected by a licit or unlawful substance. Their concerns include the negative outcomes for the worker under the influence as well as the workers working around them, there may even be a loss of property i.e. site closure.

All drugs and substances are going to have some affect, good or bad on the person taking it whether it is injected or ingested. The consumption of illegal substances may lead to negative reactions to a person’s psychology, physiology or even both. When substances are combined with legal medications there is a higher risk of negative outcomes. Undesirable reactions are always a possibility when prescribed medications are mixed with over the counter medication such as painkillers and/or alcohol. Tinsley S. Harrison states that:

“Every drug can produce untoward consequences, even when it is used according to standard or recommended methods of administration.” (Harrison, 1950)

Over time, at a constant level of dosage or at a constant substance combination consumption, various substances, medical or illicit, will usually decrease its effectiveness as a result of a chemical tolerance built within the brain and central nervous system. However, the tolerance can potentially cause a higher craving for the substance. As a result, this can often lead to a self-dosage increase and potentially a higher probability of negative psychological or physiological reactions.

In an attempt to counter the lethal combination of a hazardous working environment with substance abuse, the Health and Safety Authority enacted a clause into the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 (SHWWA). This clause required submission by employees for appropriate tests for intoxicants in order to support employers to deal with the issue.

The clause reads:

“An employee shall, while at work if necessary required by his or her employer, submit to any appropriate, reasonable and proportionate tests for intoxicants by or under the supervision of a registered medical practitioner who is competent, as may be prescribed.”

(Health and Safety Authority, 2005)

This dissertation will give an overview of the drug problem in Ireland and investigate the risks it poses if at all on our construction sites. In addition, it will look at the employer’s rights when he/she believes a worker is under the influence as well as the various remedies and actions that could be used to combat the situation as well as look at the health and safety risks arising from this situation.

1.2 Aim and Objectives

Aim

The aim of this dissertation is to investigate and examine substance abuse and its presence in the Irish Construction Industry.

Objectives

- Investigate drug abuse in Ireland and the Construction Industry.

- Examine the substances most commonly associated with workplace related accidents.

- Detail the Employer’s position and legal duties in relation to substance abuse on Irish construction sites.

- Investigate and propose possible remedies/actions that can be taken to combat substance abuse on construction sites in Ireland.

1.3 Thesis Summary

1.3.1 Chapter 1 – Introduction

The first chapter introduces the dissertation topic and briefly explains prevalence of alcohol and substance abuse in the workplace along with the aim and objectives of the thesis topic.

1.3.2 Chapter 2 – Literature Review

This chapter contains current published literature about the thesis topic and other relevant material on the matter. This chapter begins with defining substance abuse. Following this is an investigation into drug abuse in Ireland, assessing the risks on site as a result, the employer’s rights framework and actions/remedies that can be taken to combat the situation. The researcher will then form a conclusion based on reviewing the existing literature.

1.3.3 Chapter 3 – Methodology

This chapter explains two methods of research employed by the researcher to gain an understanding of the thesis topic. The primary method of research was carried out through qualitative research interviews with relevant industry professionals. The secondary method of research was employed through a desk study of previous published literature.

1.3.4 Chapter 4 – Analysis of Data and Findings

This chapter reviews the findings and evaluates the industry’s opinions which have been obtained through the process of semi-structured interviews. The findings are then analysed in order for the researcher to achieve the set objectives, outlined in Chapter 1.

1.3.5 Chapter 5 – Conclusion and Recommendations

This chapter summarises the information collected from the primary and secondary data. Once the aim and objectives have been answered, the researcher will draw conclusions and make recommendations.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

The literature review was used to establish a logical understanding of substance abuse and its effect on a person including those working in construction. The literature review was used as a secondary source of data to ensure the researcher has a complete understanding and knowledge of the topic. Additionally, it is used as a comparison for the primary data collected by the researcher. The areas the researcher has focused on are as follows: definition of substance abuse, drug abuse in Ireland, risks on site when substance abuse is a factor, the framework of employer’s rights and actions or remedies that may combat the situation.

2.2 Definition of Substance Abuse

2.2.1 Drug

A drug, in its broadest term is “any substance which changes the way the body functions, mentally, physically or emotionally.” (Eastern Regional Health Authority, 1997)

This definition does not discriminate between alcohol, caffeine, tobacco, over the counter drugs, prescribed drugs or illicit drugs. Instead it focuses on behavioural or body changes created as a result of the use of such substances. These particular substances are referred to as psychoactive drugs. This means the drug affects the central nervous system and alter mood, thinking, perception and behaviour. (Rassool, 1998)

2.2.2 Drug Use

Drug use is a broad term to cover the taking of all psychoactive substances within which there are various stages:

- Drug Free/Non-Use

- Experimental Use

- Recreational Use

- Harmful Use (Misuse/Dependence)

2.2.3 Drug Misuse

Royal College of Psychiatrists (Drug and Alcohol Review, 1987) define substance misuse as “any taking of a drug which harms or threatens to harm the physical or mental health or social well-being of an individual or other individuals or society at large, or which is illegal.”

2.2.4 Abuse

Substance abuse is described as a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, demonstrated by any of the following within a one-year period:

- Recurrent use which leads to the failure of fulfilling major role obligations (work, home, school etc.)

- Recurrent use in situations where it is physically hazardous (drinking driving)

- Repeated substance related legal problems (drunken disorderly conduct)

- Persistent use despite recurrent social/interpersonal problems caused or provoked by the effects of substances. (e.g. physical/argumentative fights with spouse)

(American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

The World Health Organisation (World Health Organisation, 2013) defines substance abuse as “the harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances, including alcohol and illicit drugs. Psychoactive substance use can lead to dependence syndrome – a cluster of behavioural, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that develop after repeated substance use and that typically include a strong desire to take the drug, difficulties in controlling its use, persisting in its use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to drug use than to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physical withdrawal state.”

2.3 Substance Abuse in Ireland

2.3.1 NACDA Survey of Drug Prevalence in Ireland 2014/15

In 2002/03, the first national survey on drug use among the general population aged 15-64 of Ireland was carried out. (National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol, 2015) The results of the survey were published by the National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol (NACDA) and the Alcohol Information and Research Unit within the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety in Ireland. The survey was repeated in 2006/07, 2010/11 and 2014/15, interviewing 4,967, 5,128 and 7,005 respectively.

In 2014/15, the survey sampled a representative number of people aged 15+ years from August 2014 to August 2015 in Ireland. The survey was carried out according to standards set out by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). The date relating to drug prevalence was categorized into used in lifetime, within the last year and within the last month.

The survey was commissioned by the NACDA in Ireland. The survey’s main focus was to obtain prevalence rates for key illegal drugs. These drugs included cannabis, ecstasy, cocaine and heroin used in a lifetime, in the last year or month.

The survey questionnaire was based on guidelines the EMCDDA drew up. The questionnaires were carried out through face-to-face interviews with participants who lived in a household aged 15+ years. Therefore, anyone living in prison for example or 15-years did not participate. The survey results were split into three stages:

- Prevalence of Drug Use and Gambling in Ireland 15+ years;

- Prevalence of Drug Use and Gambling in Ireland by Age;

- Prevalence of Drug Use and Gambling in Ireland by Age and Gender.

The definitions of lifetime, last year and last month prevalence adopted for NACDDA‘s (2015) survey are as follows:

Prevalence: “the proportion of a population who have used a drug over a particular time period.”

Lifetime prevalence: “the proportion of the sample that reported ever having used the named drug at the time they were surveyed. A person who records lifetime prevalence may – or may not – be currently using the drug. Lifetime prevalence should not be interpreted as meaning that people have necessarily used a drug over a period of time or that they will use the drug in the future.”

Last year prevalence: “the proportion of the sample that reported using a named drug in the year prior to the survey.”

Last month prevalence: “the proportion of the sample that reported using a named drug in the 30-day period prior to the survey. Last month prevalence can be referred to as current use.”

The National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol (2015) concluded that 26.4% of the Irish adults surveyed report using an illegal substance in their lifetime. For the purpose of this thesis, lifetime use does not make for significant findings as it is too vague. To gain some more significant findings, this thesis focuses more on usage within the previous year or month in which the survey was carried out. The survey found that over the previous 12 months, 7.5% of adults used some form of illegal drug with cannabis being found to being the most commonly used as 6.5% of those surveyed admitting to its use. Cannabis appears to be used significantly more than ecstasy (1.8%), cocaine (1.3%) and cocaine powder (1.2%) which followed as the 2nd, 3rd and 4th most used drug available respectively.

In the previous month alone, 4% of adults had used a drug deemed to be illegal which equates to more than half of those who have used an illicit drug in the previous year. Alcohol consumption statistics are significantly high with 77% and 62.1% stating they had consumed alcohol in the previous year and month respectively.

The National Advisory Committee on Drugs and Alcohol (2015) survey found that illicit drug use was most prevalent amongst those aged 15-24 years old with 18.7% (previous year) and 9.6% (previous month) of young people stating they had used drugs. Alcohol usage was most common among 35-44 year olds. In the previous month, the majority (>50%) of age groups bar the 65+ group consumed alcohol.

It was found that in the previous year the use of illegal drug was highest among those aged 15-24 for both genders with males (25.4%) considerably higher than females (12%). The results showed that men used cannabis at least twice as much as women across most categories.

In the twelve months prior to the survey, alcohol consumption was highest among males aged 25-34 years, with 86.4% stating they had consumed alcohol in those months compared to the highest female age group of 35-44 years at 81.7%. Similar patterns could be seen for both genders in terms of previous month usage in the 15-24-year-old range with males significantly higher than females at 13.4% and 5.8% respectively.

The (2015) survey sought to compare the use of alcohol and drugs in the most up-to-date survey against the previous surveys carried out in 2002/03, 2006/07 and 2010/11. It found that in the previous year and month prevalence rose significantly since the release of the last survey (2010/11), respectively from 7% to 8.9% and from 3.2% to 4.7%.

The prevalence of cannabis usage in the year previous rose from 6.0% (2010/11) to 7.7% (2014/15), ecstasy use from 0.5% (2010/11) to 2.1% (2014/15).

It was found that significant increases in illegal drug use among 15-34 year olds over the previous year and month compared to that in 2010/11. The use of ecstasy in the year previous rose from 0.9% (2010/11) to 4.4% (2014/15) and from 0.1% (2010/11) to 2.1% (2014/15) in the last month.

The survey found that there had been an increase in illicit drug use among both genders in the previous year and month. This is the case both since the last study in 2010/11 and the first survey carried out in 2002/03.

2.3.2 Alcohol Consumption in Ireland

The Department of Health (2012) recognise that “that individuals are primarily responsible for their own behaviour, the State has a responsibility to preserve and protect public health and the general wellbeing of society.” Alcohol plays a significant role in Irish society. Between 1989 and 1999, Ireland had the largest increase in alcohol intake among all EU countries with an increase of 41% per capita. According to the Department of Health, alcohol is responsible for many of Ireland’s health and social harms in society and places a huge burden on the State’s resources in dealing with the consequences of alcohol use and misuse. A number of interventions are needed in order to reduce alcohol-related harm across the country. The World Health Organisation (2009) state that alcohol interventions that targeted vulnerable groups can prevent alcohol-related harm but policies targeted at the population as a whole, while having a protective effect on vulnerable populations, reduces an overall level of alcohol problems.

According to the Department of Health (2012) Irish adults drink more dangerously than that of any other country. The department found that the average Irish adult drank 11.9 litres of pure alcohol in 2010 which in context equates to 482 pints of beer, 125 bottles of wine or 45 bottles of vodka. Although the consumption of alcohol has reduced since 2000, adults in 2010 were drinking more than twice the average of alcohol consumed per adult in 1960. Similar findings were made by the OECD (2011) who found that Ireland’s alcohol consumption in 2009 per capita was 11.3 litres per adult (15+ years) which was the tenth highest of 40 countries that the report covered in 2009. The average amount of alcohol consumed in 2009 was 9.1 litres per adult. The European Commission (2010) found that Irish adults binge drink more than any other European country, with 25% of Irish adults reporting that they binge drink on a weekly basis. Over 50% of Irish drinkers identified themselves as having a harmful drinking pattern equating to c.1,500,000 Irish adults. Morgan (2009) found that Irish children are drinking from a younger age and drinking more than before.

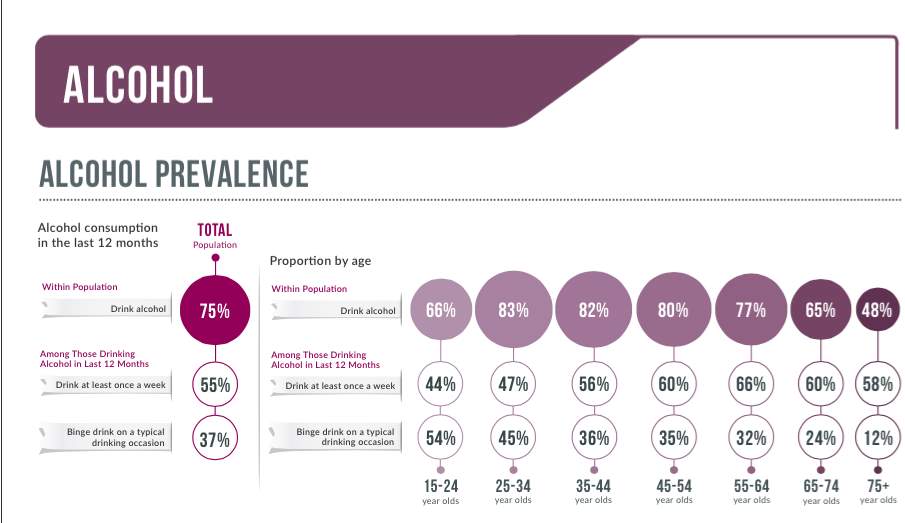

The Healthy Ireland Survey (Department of Health, 2016) found that three quarters of the Irish population consumed alcohol in the last year. The results of the survey shown that 55% of drinkers, drink at least once a week, with those aged 55-64 drinking the highest weekly (66%). There was a significant difference between male and female whom are 35+ and drink at least once a week, 68% and 52% respectively.

During a typical drinking session, 37% of drinkers indicated that they drink six or more standard drinks. The majority of men who do drink, binge drink on a typical occasion (55%), far more than women with 1 in 5 drinking to this level. The majority (54%) of drinkers aged under 25 binge drink on a typical occasion, 67% in men and 39% in women.

The survey found that 97% of drinkers consider themselves to be light or moderate drinkers while a quarter of drinkers stated that they occasionally binge drink. 29% of people who do not class themselves as an occasional binge drinker drink six or more alcoholic drinks at least once a month. Despite binge drinking on a typical drinking occasion, 57% of drinkers aged under 25 consider themselves to be light drinkers.

Figure 1 – Alcohol Prevalence in Ireland – Healthy Ireland Survey, 2016

Figure 2 – Description of own drinking behaviour – Healthy Ireland Survey, 2016

The Department of Health (2012) found that 4,321 deaths between 2004 and 2008 were due to either alcohol poisoning or deaths in alcohol dependent people, equating to 88 deaths each month in 2008. During the four-year period, alcohol cause nearly twice as many deaths as all drugs combined. While during 2000-2004, alcohol caused 4.4% (6,584) of deaths in Ireland including deaths as a result of accidental and non-accidental injuries that occurred to those under the influence of alcohol. (Martin, et al., 2010).

2.3.3 Prevalence of Substance Use in the Construction Industry

Construction Industry workers report higher than average rates of at-risk alcohol use, use of illicit drugs, use of tobacco and moderate or heavy smoking. The Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission (AADAC) (2002) conducted a prevalence survey in which they found that the construction industry was regarded as a group of concern in terms of rates of substance use. Lipscomb & Li (2003) carried out a large work-group study in America between 1989 and 1998. Through this study they found that 6.6% of the workers had received a substance abuse-related diagnoses.

Smoking

Through a study of health interview data sets in the U.S, the highest smoking rates were reported in the construction industry with 39% revealing they smoked (Smith, 2008). Alvania, et al (2009) found that smoking was a factor in longer-term sick leave.

Alcohol

Through a national sample conducted by Larson, et al (2007) of full-time American workers aged 18-64, construction workers had the highest rate of past month alcohol use compared to workers in all other industries at 16%.

A survey carried out by Iacuone (2005) which took place in Victoria, Australia at several construction sites over a six month period found that the consumption of alcohol is an important aspect of male culture in the construction industry and that there is a certain pressure for a nondrinker to become a drinker. Data collected in 1997 in the US states that there was almost double the amount of heavy alcohol users among construction workers (12.4%) than the national average for other industries (7.6%) (Rountree, 2002). As well as this a Cundrai, et al (2009) survey conducted in the U.S. found that 17% of male construction workers surveyed could be designated as problem drinkers.

Illicit Drug Use

In 2002, it was estimated that 16,738 workers in Alberta used drugs while at work. While there was variation in the use of illicit drugs by industry and occupation, above average rates of drug use was reported in the construction industry (Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission, 2002). This was similar to data cited by Rountree (2002) in which it was found that the percentage of illicit drug users among construction workers (14.1%) was double the national average for all industries (7.7%).

In March 2001, Mace’s site manager on the £250m SmithKline Beecham headquarters project in Brentford received anonymous phone calls warning him that drugs were being dealt on site.

He decided to contact the police who came to site and warned the 2000-strong workforce that they were being monitored and that undercover members of the police force would be trying to catch the dealers. The police as well as local anti-drugs campaigners came to site to give advice to workers about drugs and, together with Mace, made them aware of the dangerous risks drug use can have on construction sites.

John Hanley, Safety Officer at Mace said “the only way to deal with the problem was to introduce the right kind of deterrents so news of the clampdown would get around and bring any problems into the open. It is totally unacceptable that anyone high on substances should put fellow workers’ lives at risk.”. (Broughton, 2001)

According to Broughton (2001) anecdotal evidence is showing that on sites across the UK, drug use goes unchecked. It is hard to know how far the drug use culture is pervading the industry. Up to now, there has been no statistics from the Health and Safety Authority to link drug use to accidents. The majority of construction firms remain ignorant if the scale of the problem, but those who have observed the culture first hand must be tackled. (Broughton, 2001)

Alan Ritchie, a representative of the Union of Construction Allied Trades and Technicians (UCATT) in Glasgow says “When you think we have an ageing workforce that is going to be replaced by young people who could bring in a new drug culture, the industry will need to look at what measures need to be adopted to tackle [drugs].” (Broughton, 2001)Ritchie was involved in a case in which a member of UCATT alleged that drug use was taking place among construction workers on the £78m Millennium Wheel site in Falkirk, Scotland. Barry McDonald, a labourer on the job, claimed to have seen workers under the influence of cannabis and other substances. He even claims to have seen workers heat up marijuana in the canteen microwave. Morrison Construction, the main contractor on the job, launched an immediate investigation. A spokesman said “It must be remembered that the allegations are referring to probably only a couple or a handful of people from a site of 800 workers. Things needs to be kept in perspective.” Barry McDonald then left his job claiming intimidation from co-workers, “drugs are a big problem on building sites and people are making a real lot of money from dealing them.”(Broughton, 2001)

A graduate trainee working in London who did not want to be named says that “Saturday mornings are the worst……most of the team have been out on a Friday night and are still high on ecstasy, amphetamines and cocaine.” He says “I have recommended to lads whose pupils are still bulging from the night before that they go home because they are just not safe enough to operate machinery. You often get lads who are on something on site, whether it’s speed or some kind of pill taken to get them through the day. The problem is they often think they are Superman and try to jump from high places or lift a crane. They are the most dangerous.” (Broughton, 2001)

A labourer also from a site in London, who wished to remain anonymous, claims that he has also witnessed drug dealing on site. He believes it is something site managers are aware of and sometimes even overlook as it maintains worker morale. He says “There is one particular site in London where a lad has been dealing drugs for months. It’s not really done underhand; everybody knows he’s the man to contact to score drugs, and he knows he has a large marketplace to make money.” (Broughton, 2001)

Broughton (2001) writes that in November 1999, on site drug use hit national headlines when ecstasy and cannabis were reported being dealt during construction of the Millennium Dome. Employees of Northern Ireland-based firm Mivan were accused of dealing and taking drugs while working on two of the project’s 14 zones. Charlie Hutchinson, Mivan’s health and safety manager said “in our case the police didn’t want to know because the claims couldn’t be substantiated, but at the end of the day the contractor is liable and responsible for their employees.” Hutchinson believes that it is unfair that contractors are solely responsible for employees with sufficient powers to control and police them. He talks about sites in Florida in which drugs were eliminated from sites by random testing, “in the USA, drugs in the workplace are not tolerated. If we are to be responsible for employees, we too need some kind of powers to monitor workers, but here human rights legislation limits us from doing so.”

According to the International Labour Organisation (Drug and Alcohol Abuse Prevention, 2003) alcohol-related problems are more common in the work place than drug-related problems. O’Connor & Keenaghan (Alcohol and drugs in the workplace; attitiudes, policies and programmes in Ireland, 1993) state that Irish employers are of the opinion that absenteeism is the chief manifestation of alcohol abuse in the workplace. Studies carried out by Mangione, et al (Employee drinking practices and work performance, 1999), Bass, et al (Employee drug use, demographic characteristics, work reactions and absenteeism, 1996) & Normand, et al (An evaluation of pre-employment drug testing, 1996) have all shown the relationship between substance abuse and workplace absenteeism. There is also evidence available that shows a negative relationship between mixing drugs and alcohol and work performance (Lehman & Simpson, 1990) and that substance misuse is often associated with higher levels of injuries and accidents occurring at the workplace (Wells & MacDonald, 1999).

2.3.4 Forms of Substances and their effects

According to Designing Building (2017) “Construction projects, in particular, large and complex projects, are increasingly dependent on construction plant, and there are a wide range of issues that need to be considered in its use” including public and employee safety. Health and safety in particular is vitally important in the operation of plant on site particularly in regards to cranes, mobile plant and vehicles.

Hawkes Group state in their company drug and alcohol policy that “machine fitters/plant operators/lorry drivers/ground workers are requested to immediately report the use of any prescribed and/or over the counter medication that may have side effects while working whilst under the employment of Hawkes Plant Limited to the Management Systems Coordinator prior to embarking on the drugs.”

Hawkes Plant Limited will not accept any one to present themselves for work whilst under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Anyone is breach of this will be dealt with in accordance with the company’s disciplinary procedure. Hawkes Plant Limited’s machine fitters/plant operators/lorry drivers/ground workers must not:

- Report, or try to report, for duties when unfit for work through drugs or alcohol;

- Consume alcohol or drugs while on duty;

- Be in possession of alcohol or drugs on work premises;

- Drink 12hrs before or while on duty or take drugs at all;

- Wear high visibility or Hawkes Plant Limited identification or uniform on licensed premises;

- Use any drugs at any time;

- Have the smell of alcohol whilst on duty;

- Accept call for duty if in breach of any of the above or if they have any doubt about fitness to work. (Hawkes Group, 2016)

The following are different forms of drug that may have an effect on a plant and machine operator’s ability to drive or operate plant or machinery on site:

Alcohol

There have been studies that show that, in cases in which involvement in traffic accidents is concerned, no drug has been found to be as prevalent than that of alcohol. The majority of experimental studies have shown impairment on one or several performance skills at one or more BAC’s (blood alcohol content), with most impairments beginning at when the BAC is at or below 0.07g/dl (grams per decilitre). Experiments through simulators and on-the-road have typically shown alcohol to have deleterious effects on a number of driving skills including brake reaction time, ‘collision’ frequency, steering responsiveness and lane control, as well as the requisite cognitive skills such as risk-taking appreciation, planning and decision making. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

Methadone

A series of studies have suggested that, in cases in which an individual has recently started using, the effect of acute methadone administration is to produce a dose-dependent reduction in reaction time, in visual function as well as information processing. In cases in which new patients on a maintenance program are concerned, literature suggests that it is recommended to allow a period of up to 30 days during which they should not drive. Like many drugs, methadone “can potentiate the deleterious effects of alcohol”. Both experimental and field studies suggest that methadone use does not result in significant driving impairments that deem the user ‘unfit’. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

Cannabis

Although there is some conflicting evidence, it seems that cannabis does not significantly impair very basic perceptual mechanisms. However, cannabis does impair more subtle aspects of perceptual performance for example, attention and short-term memory, however these are most often seen in high doses. The majority of experimental studies have used low dose of cannabis and this may not reflect the does used by heavy marijuana users. Studies have demonstrated that cannabis is one of the most prevalent drugs discovered in the urine and blood samples of drivers. The assessment of the casual role of cannabis in accident occurrence us complicated by the fact that alcohol is most generally present in samples. When cannabis is mixed with alcohol, it is much more likely to be a risk factor than when consumed alone.

Benzodiazepines

The sedating effects of benzodiazepines can potentially cause some impairments on psychomotor tests. Studies have shown that benzodiazepines are the most frequently detected illicit drugs in all driver groups. Various authors have concluded that some benzodiazepine tranquillisers can impair driving skills throughout the first number of weeks of treatment, but these effects may deplete with continued use. Xanax and Valium are examples of a benzodiazepine. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

Antihistamines

Experiments have suggested that peripherally active as opposed to centrally active antihistamines are less likely to cause any form of impairing sedative effects. Some forms of antihistamines are slow in crossing the blood brain barrier and therefore produce tolerance without central effects such and astemizole and terfendine, are more likely to have little detrimental effect on skill performance. Antihistamines vary in their effects on impairments and it is important that pharmacists, general practitioners, nurses and the general public are informed about the need of using the least sedating drugs that are available. Through studies, it is found that antihistamines are seldom suggested as causative factors in traffic accidents. Similar to cannabis, where antihistamine traces are found in fluid samples, alcohol is also presents in many cases. However, there is evidence to suggest that antihistamines potentiate alcohol effects. Generally, the use of peripherally acting antihistamines is not very likely to cause any impairments in driving performance. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

Antidepressants

Investigations have suggested that antidepressants can have both positive and negative effects on psychomotor performance. Various studies have found that patient’s performance may improve as the result of the drugs relieving their depressive symptoms, however, more needs to be known about the effects of depression on the individual’s ability to drive. There is no clear picture from studies regarding the antidepressant levels responsible for traffic accidents compared to the overall driving population. There is insufficient research available on the newer, less sedative antidepressants regarding their effects on psychomotor performance. In the most popular antidepressants such as fluoxetine, the most common side effects sucg as nausea and insomnia can in itself effect driving. In situations where alcohol is combined with antidepressants, more so in the more sedative types, the worst impairments are often seen in the initial phase of treatment as diminish after treatment. Still, alcohol is the bigger problem and the effects of severe, untreated depression on driving capacities may be worse than the effects of antidepressants. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

Amphetamines

Studies have shown that at lower risk doses amphetamines have little effects on cognitive functioning, however at higher doses risk-taking increases and responses are more inappropriate. Lower doses can result in an enhancement of various psychomotor tasks. There is insufficient evidence to specifically implicate amphetamine use in traffic accidents due to the lack of studies. Few studies have directly examined alcohol-amphetamine interactions and the results appear to be contradictory. Generally, high doses of amphetamine are likely to increase the impairing effects of alcohol, Therefore, there may be subjective positive stimulant effects associated with the use of amphetamines, although, these effects, more so at higher does could result in a change of personality leading to a more likelihood of impaired driving. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

Ecstasy and Other Synthetic Drugs (GHB, Ketamine, PCP, Fentanyl, Ephedrine and Phentermine)

It is evident from comparatively inadequate literature on MDMA and various other synthetic drugs and driving that more research is needed in order to increase the understanding of the impairing effects of this drugs. Most research has concentrated on the short-term effects of MDMA but little is known of the consequences through use in the long-term. Ecstasy tablets are often made up of numerous, potentially toxic elements, the combined effects of which are mostly unknown. Likewise, there is very little evidence concerning the effects of GHB, ketamine, PCP, fentanyl and abused diet drugs on an individual’s driving abilities and in most field studies they are not detected often. Given the known side-effects of these drugs however and especially given the perception-changing effects of some. Notably PCP and fentanyl, it is likely that the establish a danger where driving is concerned. (Gemmell, Moran, Crowley, & Courtney, 1999)

2.4 Substance Abuse Related Workplace Accidents

According to Laad, et al (Prevalence of substance abuse among construction workers, 2013) the construction industry is among the largest economic activities of which plays a significant role in the nation’s economy. A lack of greater employment in various other sectors has drawn large numbers of workers to the construction industry in years before ‘The Crash’. Laad, et al (Prevalence of substance abuse among construction workers, 2013) notes that heavy physical work is required by workers in the construction industry while living in a run-down environment. The lack of recreational activity, company of friends, unhygienic situation encourages workers to take part in certain negative activities. Laad, et al (Prevalence of substance abuse among construction workers, 2013) repeats that substance abuse is often influenced by various factors including individual attitudes and beliefs, social norms and easy affordability. Often, workers believe that alcohol and tobacco use can benefit them in their work, however there are a lot of misconceptions. Cook, et al (The Prevention of Substance Abuse among Construction Workers: A Field Test of Social-Cognitive Programme, 2010) challenges the benefits that include helping the workers to suppress appetite, increase concentration, induce feeling of pleasure and reduce tension. Laad, et al (Prevalence of substance abuse among construction workers, 2013) reports that the construction industry makes up some of the highest rates of substance abuse, with the rate of current illicit drug use said to stand at around 14.1%.

The Government of South Australia (2006) believe that guidelines for addressing alcohol and other drugs in the workplace suggest that there is a necessity to identify hazards associated with the use of alcohol and other drugs in the workplace as well as the risk assessed and strategies developed to control the risk similar to any other occupational safety hazard. There needs to be consideration for a range of factors when assessing whether alcohol or drug use poses a health and safety risk within the workplace. Consideration towards the effect of drug intoxication and the hangover effects of drug must be made. Depending on the nature of the workplace the risk associated with alcohol and drug use may be greatly increased. Workers who operate machinery, drive or rely on construction or motor coordination may be at an increased risk of injury if affected by alcohol or other drugs. Workers who use heavy machinery or hazardous materials in their line of work, for example, may be at risk of more serious harm if injured.

The Government of South Australia (Guidelines for addressing alcohol and other drugs in the workplace, 2006) notes further that in some occupations, a worker whom is affected by alcohol of another form of drug may be more likely to place risk on the health and safety of others, for example, when moving hazardous materials or performing duties while part of a team. Alcohol and drug consumption may also be more prevalent in some industries than others. This is backed up by the U.S. Department of Labour who state:

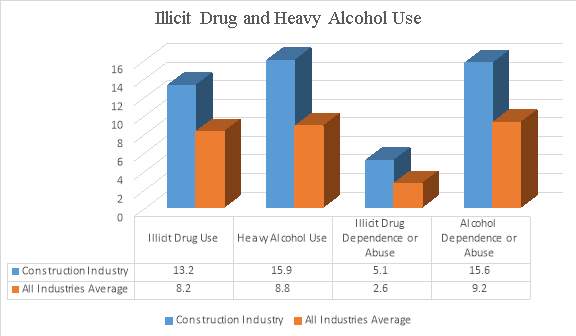

“The major industry groups with the highest prevalence of heavy alcohol use was construction, arts, entertainment and recreation, and mining, and those with the lowest were healthcare and social assistance and educational services”.

Figure 3 – Illicit Drug and Heavy Alcohol Use – U.S. Department of Labour

The above chart, provided by the U.S. Department of Labour highlights that heavy alcohol and illicit drug use as well as their dependence or abuse is more prevalent in the construction industry than the average of all other industries. Illicit drug use in the construction industry stands at 13.2% of those surveyed while the average of all other industries stands at 8.2%. Illicit drug dependence or abuse in the construction industry (5.1%) is nearly double that of the average of other industries (2.6%). Alcohol dependence or abuse proves to be more prevalent in construction (15.6%) than in other industries (9.2%).

An employer is required to minimize any risk caused by alcohol or other drug use in their workplace under their general duty of care to provide a safe working environment.

According to the work of Larson, et al (Worker Substance Use and Workplace Policies and Programs, 2007) three out of the five occupations with the highest prevalence of current illicit drug use were dominated by males. Larson, et al (Worker Substance Use and Workplace Policies and Programs, 2007) states that an estimated 97.4% of construction workers were male with similar figures showing in installation of maintenance and repair, and transportation and material moving at 96.2% and 87.2% respectively.

A survey carried out by Hogan, et al (Construction apprentices’ attitudes to workplace drug testing in Ireland, 2006) notes that 4.6% of the construction apprentices that were surveyed reported having an accident due to the use of alcohol while 3.6% reported to having an accident due to drug use. Hogan, et al (Construction apprentices’ attitudes to workplace drug testing in Ireland, 2006) further stated however, that if those percentages were applied to the total number of apprentices in the country (15,614 – construction apprentices) and if 4% of apprentices reported an accident due to the use of alcohol or other drugs, 625 people would suffer an accident in a year with alcohol or drug use contributing to the accident.

The researchers found that 40% of the respondents had reported feeling drunk in the year previous and 82.1% reported feeling hungover having consumed alcohol the previous night. As a result of drinking, 45.7% missed days from work, 70.7% felt tired at work and 62.9% left early or arrived late. Drug use, however, seems to impact less on work, with only 2.9% missing days from work and 9.3% leaving early or arriving late with only 10% feeling tired and 6.4% feeling hungover at work.

2.4.1 Reviews on Relationship between Substance Abuse and Misuse and Occupational Injuries

In 1993 and 1994, literature was reviewed with the aim of investigating the relationship between substance use and misuse and occupational injuries. In the first of the two reviews, Stallones & Kraus (The Occurrence and Epidemiologic Features of Alcohol Related Occupational Injuries, 1993) found that there was not enough evidence available to establish a relationship between alcohol use and misuse and workplace injuries. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) carried out their own review a year later on drugs and the American workforce (Normand, Lempert, & O’Brien, 1994). The IOM’s report conducted a more detailed review of the impact of alcohol and other drugs in the workplace and their outcomes including job satisfaction, absenteeism and accidents. The Committee concluded that while there was evidence that substance abuse effected job behavior and occupational outcomes including injury negatively, substance use’s influence on these injuries were small. However, the IOM’s study shows that there is a lack of analytical approaches to the study limiting their ability to say anything definite about a drug/accident relationship. Most available studies lacked controls for personality traits and other risk taking dispositions in multivariate models. Both Stallones & Kraus (The Occurrence and Epidemiologic Features of Alcohol Related Occupational Injuries, 1993) and IOM noted that very few studies employed a control group therefore limiting their ability to estimate differential risk between using and non-using groups.

2.4.2 Alcohol Use and Occupational Injuries

A number of different studies found wide, positive effects on self-reported alcohol use on occupational injuries. The relationship between alcohol use and work-related injuries was carried out by Stallones & Xiang (Alcohol consumption patterns and work related injuries among Colorado farm residents, 2003) among farm residents in Colorado between 1993 and 1995. The consumption of alcohol had a large effect on reporting a work-related injury. Those who drank alcohol three or more on average, had about 3.2 injuries per 10,000 person-work-days (c. 40-years’ work) compared to 1.9 injuries per 10,000 for those who do not drink alcohol, a 70% increase in risk. 3.2 injuries per 10,000 person-work-days is a yearly rate of 8 injuries per 100 workers. The rate for non-drinkers would be 4.8 injuries per 100 workers. Therefore, if 10 million workers are drinkers (from 140 million) there would be over 320,000 yearly injuries due to alcohol. Dawson (Heavy drinking and the risk of occupational injury, 1994) noted a positive relationship between drinking five or more drinks daily in the past twelve months and having a workplace injury among respondents in the 1998 National Health Interview Survey (Odds Ratio* – 1.74). (Shipp, Tortolero, Cooper, Baumler, & Weller, 2005) investigated the rates in the previous month (30 days) and self-reported injuries while working for income among secondary-school students in Texas. The research found a dramatic increase in risk between light users (OR* – 1.56) who drank 1-19 days in the last 30 days and heavy users (OR* – 10.55) who drank every day in the last 30 days.

Wells & MacDonald (The relationship between alcohol consumption patterns and car, work, sports and home accidents for different age groups, 1999) found through a telephone survey in Canada that increased drinking was associated with a larger number of self-reported accidents among 15-24 year olds but not for older groups. However, those that drank more than 14 times a week were more than likely to report having an accident at work. Mangione, et al (Employee drinking practices and work performance, 1999) found that very light- moderate drinkers reported half as many injuries to that of heavy drinkers. However, these positive results were balanced by studies that used self-reports and found no effects of alcohol and injury at work. Ames, et al (The relationship of drinking and hangovers to workplace problems, 1997) found no effect of any of their measures of drinking behaviour on workplace injuries on a group of manufacturing workers. However, they did note a significant effect of drinking and other problems in the workplace i.e. disputes with colleagues and sleeping at work. Hoffman & Larison (Drug use, workplace accidents and employee turnover, 1999) as well as Veazie & Smith (Heavy drinking, alcohol dependence and injuries at work among young workers in the United States labour force, 2000) also found little reason to conclude a positive relationship between drinking alcohol and injury in the workplace.

| Source | Sample | Measure of Substance Use | Injury | Findings |

| (Dawson, 1994) | 29,192 adults interviewed in National Health Interview Survey 1988 | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol (≥5 drinks over number of days in last year. | Self-Report – Injury at work in last year. | Frequent and less frequent heavy drinkers were more likely to report an on-the-job-injury. |

| (Ames, Grube, & Moore, 1997) | 832 hourly employees in a U.S. manufacturing plant over 5 years | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol (before, during and after work and working when hungover). | Self-Report – Injury at work in last year. | Alcohol was not associated with injury but was associated with sleeping at work and fighting with co-workers. |

| (Hoffman & Larison, 1999) | 9,097 workers in National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 1994 | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol over the last year. | Self-Report – Injury at work in last year. | No association was found between alcohol and work related accidents. |

| (Mangione, et al., 1999) | 6,549 employees from 6 sites, 1994 | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol. | Self-Report – Injury at work in last year. | There is a relationship between alcohol use and injuries with heavy drinkers having the highest injury rate. |

| (Wells & MacDonald, 1999) | 10,385 Canadians (15+) | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol (quantity and frequency in past week and 12 months). | Self-Report – at least one work accident in last year. | Heavy drinking was associated with self-report of having at least one accident in last 12 months. |

| (Veazie & Smith, 2000) | 8,569 in National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (24-32) | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol (quantity and frequency currently, dependence). | Self-Report – Injury (exc. Strains and sprains) in past 6 months at work. | No link was found between work related accidents and alcohol consumption. |

| (Stallones & Xiang, Alcohol consumption patterns and work related injuries among Colorado farm residents, 2003) | 872 farm residents in Colorado | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol (quantity and frequency in past week and month). | Self-Report – Injury at work in last year. | Farmers who drank more often had higher injury-incidence rates. |

| (Shipp, Tortolero, Cooper, Baumler, & Weller, 2005) | 3,365 high-school students in South Texas, 1995 | Self-Report – Use of Alcohol and Drugs over the past 30 days (alcohol and cannabis), lifetime use (cocaine, inhalant and steroids). | Self-Report – Injury while working for income – lifetime. | Risk of injury increased for all substances with higher rates of current and lifetime use. |

Figure 4 – Findings of other researchers on alcohol use and occupational injuries

* An odds ratio (OR) is a measure of association between an exposure and an outcome. The OR represents the odds that an outcome will occur given a particular exposure, compared to the odds of the outcome occurring in the absence of that exposure

2.4.3 Drug Use and Occupational Injuries

Hoffman & Larison (Drug use, workplace accidents and employee turnover, 1999) also examined the impact of drug use on occupational injuries during their analysis of the 1994 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. They found no evidence of a relationship between drug use (cannabis and cocaine) and occupational injuries. However, this finding is different to the findings of three other studies who all found significant evidence of positive relationships between self-reports of the use of drugs and occupational injuries. Shipp, et al (Substance use and occupational injuries among high school students in South Texas, 2005) looked at the frequency of alcohol consumption, binge drinking and cannabis usage over the past month as well as lifetime usage of cannabis, cocaine, inhalant and steroids. The study consisted of 3,365 Texan high-schoolers who were currently working. The study found that there was an increase in the odds of reporting an injury if there was an increase in the frequency of substance use. Frone (Predictors of work injuries among employed adolescents, 1998) also studied high-school aged workers and found that self-reported on-the-job substance use had a high positive effect on the chances of an injury occurring. However, he did not find a relationship between general substance use and injury. Kaestner & Grossman (The Effect of Drug Use on Workplace Accidents, 1998) found that the use of cannabis and cocaine in the past year increased the chances of reporting a workplace accident over a year by 25% in men, however, there was no evidence of a relationship among women.

2.5 Employer’s and Employee’s duties in relation to drug use in Ireland

2.5.1 Employer’s and Employee’s duties

There is no requirement for a worker to undergo testing for intoxicants under current health and safety legislation. Similarly, employers do not have a legal obligation to test their employees for intoxicants. As previously mentioned in the introduction there is a clause 13(1)(c) in the (Health and Safety Authority, 2005) Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 (the Act) which allows for regulations to be made for intoxicant testing. However, this clause does not apply today until the regulation is introduced by the relevant Minister.

The Act defines intoxicant as alcohol and drugs and any combination of drugs and alcohol. It includes both legal and illegal substances meaning over-the-counter and prescribed medications are included.

The relevant duties of the employer are set out in Section 8 of the Act (Health and Safety Authority, 2005). These duties require the employer to ensure, so far as reasonably practical, the safety, health and welfare of all his or her employees. This includes managing and conducting work activities to prevent improper conduct or behaviour that will likely put employees at risk. Section 19 (Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005, Section 19, 2005) and 20 (Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005, Section 20, 2005) of the Act state that employers must identify hazards in the workplace; to have a written assessment of the risks as a result if those hazards in the workplace, the safety statement should state it.

While at work, an employee must ensure that he or she is not under the influence of an intoxicant in which they could endanger themselves or the other people present at the time, Section 13(1)(b). The employee must also fully co-operate with their employer to comply with health and safety law e.g. an employer should inform their employer if they are taking any medication that may pose a risk to other workers.

Where intoxicants at work is identified as a hazard it must be entered within the safety statement of the company. Although there is no requirement for testing of employees, employers should address whether the employee’s behaviour poses a risk of danger to himself/herself or others. The correct course of action would be to remove the employee from the situation if it is the case. Where testing is part of the company policy or has been put into their employee’s contract, it is recommended that tests are carried out in accordance with a recognised standard i.e. European Laboratory Guidelines for Legally Defensible Workplace Drug Testing.

2.5.2 Disciplinary Procedure

Other than any enforcement action by the Health and Safety Authority in regards to breach of employee duties, any employee who does not adhere to requirements of statutory regulations and/or site safety rules may be liable to disciplinary action. This could be the employer’s disciplinary procedures up to and including dismissal.

Breaching any safety procedure is a very serious matter with some breaches a lot more serious than others and may warrant summary dismissal. Among the many breaches of safety breaches, reporting for work whilst under the influence of alcohol or drugs is one of the more serious of breaches. This would be considered an act of gross misconduct warranting summary dismissal. Any allegations would be investigated thoroughly and would comply with natural justice. (Construction Industry Federation, 2003)

2.6 Remedies and Actions of preventing Substance Abuse in the workplace

2.6.1 Treatment Recommendations

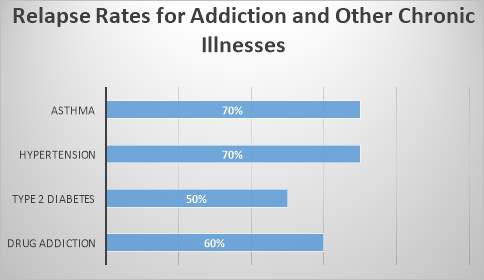

By reducing employee substance abuse employers can decrease health care costs, reduce injuries in the workplace and improve productivity. Like asthma and diabetes, there is an understanding that substance addictions are chronic addictions.

Similar to these chronic conditions, addiction to substances can be managed successfully. However, it is not uncommon for a person to relapse or in terms of substance addiction, begin to abuse substances again. Relapse does not mean failure; it simply means that treatment is necessary again or a different form of treatment is required. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007)

Figure 5 – Relapse Rates for Addiction and Other Chronic Illnesses – (McLellan, Lewis, O’Brien, & Kleber, 2000)

Identifying Substance abuse early can save employers and companies money in terms of health and productivity costs. An employer substance abuse programme may include workplace policies, drug testing, employee educational promotion, employee assistance programmes (EAP’s) and health plan treatment coverage.

A complete employer substance abuse programme shall include:

- Confidential screening by an EAP or health professional.

- A workplace substance abuse education component.

- Treatment referrals to an EAP or health professional.

- Confidential follow up care for supporting any employees in recovery.

2.6.2 Workplace Policies and Drug Testing

A substance abuse policy may implement a drug-free workplace initiative. A complete substance abuse policy might include: (Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, 2005).

- Purpose and objectives of the policy;

- A definition for substance abuse;

- Who is covered by the policy;

- Under what conditions will drug testing (inc. alcohol) be conducted;

- Confidentiality rights of the employee;

- Educational opportunities regarding substance abuse for employees e.g. substance-free awareness programme;

- Training for employees for identifying impaired behaviour and other signs of substance abuse;

- Guidance on how to deal with impaired workers;

- Provisions for supporting and helping chronic substance abuse;

- Disciplinary actions.

Some industries have specific legal obligations to address workplace substance abuse. For example, employers in transportation must ensure the safety of their employees and the public travelling on their mode of transportation.

It is essential that companies or employers are completely aware of patient/employee substance abuse confidentiality rules. Federal regulations regarding the confidentiality of patient’s records of drug and alcohol use have been issued by the Department of Health and Human Services. Employers must emphasise with the assurance their privacy will be protected.

2.6.3 Employee Assistance Programmes (EAP)

Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) access is offered to employees by the majority of large employers. The EAP have expertise in providing information, referrals and counselling on issues such as substance use, stress, family problems, mental health and work. The EAPs guide employers in addressing various employee problems and proactively deal with workplace issues that may lead to violence, declining morale and physical and mental health issues. The programmes are staffed by professionals who provide the individuals and their families with prevention services and short term problem-resolution services. The EAPs provide, what could be very helpful in the construction industry, confidential substance screening, education, recovery support and referrals for treatment. Other than the health benefits the programmes offer, they play a major role in encouraging employee wellness while reducing substance abuse among various other health problems. (Employee Assistance Professionals Association, 2017).

2.6.4 Health Plans

National Business Group on Health (An Emplyer’s Guide To Workplace Substance Abuse, 2009) highlight that health plans should provide coverage for substance abuse screening, therapy, counselling and aftercare. By offering a comprehensive health plan with benefits, employers can help make treatment successful. A broad range of services the plan supports are:

- Confidential substance abuse screening;

- Brief intervention;

- Outpatient and inpatient treatment;

- Medication;

- Peer support groups;

- Illness self-management programmes;

- Counselling and medical services;

- Follow-up services during treatment and recovery.

2.6.5 Workplace Health and Wellness Programmes

An employer can play a major role in preventing the hazardous use of legal and illegal substances by:

- Making it clear that drinking and the use of illicit drugs on site is not condoned;

- Combating the stigma workers have against looking for help and promoting that employees can seek treatment confidentially without jeopardizing their jobs;

- Stating information of the appropriate use of alcohol and various legal substances such as prescribed medication and over-the-counter medication into a wellness and risk prevention strategy;

- Provide factual information to employees on the harmful effects alcohol and drug use has on them;

- Informing employees of the health and safety risk excessive or binge drinking outside of work has.

(Human Resources Council, 2017)

2.6.6 Treatment

The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) define treatment as “in-or-out-patient services that focus on initiating and maintaining an individual’s recovery from alcohol or drug abuse and on preventing relapse.”

A large number of individuals with a substance abuse disorder do not receive the care they require. Mark, et al (Spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1987-1997, 2000) found that 47% of men and 41% of women in need of drug use treatment are not treated. The strongest argument for the use of the solutions that this dissertation has to offer is the opportunity to reduce the monumental costs in terms of health, disability and liability that companies experience due to undiagnosed and untreated substance abuse. As shown in Fig.10, treatment for substance abuse is just as successful as treatment for asthma, diabetes and other chronic diseases. Previous studies have shown that up to 70% of patients treated for substance dependence recover. (American Psychiatric Association, 2000)

Those who seek and receive treatment for their addictions have:

- Better long-term outcomes;

- Improved long-term health;

- Reduced relapse;

- Improved family and other relationships. (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2002)

2.6.7 Screening and Assessment

Screening is carried out in order to determine whether or not an individual shows any clear indicators of substance abuse. The answer is simply yes or no. The process attempts to quickly identify potential or current substance abusers so that appropriate interventions can be provided. There are many ways in which screening can be done including in the workplace, at home, online or in a physician’s office. In many cases screening may be the first recovery step. (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2017)

According to O’Connell (A systematic review of the utility of self-report alcohol screening instruments in the elderly, 2004) the CAGE was the most widely used screening tool followed by Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). They found that the newer instrument, the AUDIT-5 is showing some promising results. The Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory (SASSI) is used to identify alcohol and drug abusers and differentiate them from social drinkers etc.

Assessment is a process for defining the nature of that problem, determining a diagnosis, and developing specific treatment recommendations for addressing the problem or diagnosis. (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2017)

2.7 Case Study

2.7.1 ‘Spotlight On’ Scheme

Throughout the Construction Industry in the UK, alcohol and drugs have been recently placed under the Considerate Constructors Scheme after the results of a survey revealed that 59% of people working within the industry are concerned over the effects drugs and alcohol have on the industry.

The ‘Spotlight On’ campaign scheme focuses on taking the various measures necessary to protect and safeguard the entirety of the workforce in relation to drugs and alcohol.

A survey recently carried out with over 1300 people working in the industry discovered that 59% have concerns over the effects of drug and alcohol in construction and yet 65% have never been tested for either alcohol or drugs.

The survey, which was conducted by the Considerate Constructors Scheme in May of 2016 also revealed:

- 39% admitted the issue of drugs and alcohol could be better tackled in their workplace;

- 35% have noticed their co-workers under the influence of drugs and alcohol;

- 25% agreed drugs and alcohol affected them at work through tiredness;

- 23% agreed it affected them through decreased attention during work;

- 19% agreed the effects made them less productive at work.

Many contractors as well as suppliers and clients of the construction industry undertake ‘rigorous and regular measures’ to tackle the issue which includes zero tolerance to alcohol and any form of drug, random testing, providing information regarding drugs and alcohol through toolbox talks, site inductions and resources such as posters around the site.

(Safety & Health Practitioner, 2016)

A number of Scheme-registered contractors have provided case studies on how they tackle this issue, including: John Sisk & Son Ltd, Ballymore and Mulally and Co Ltd.

Case Study: John Sisk & Son Ltd

Sisk have a Substance Abuse policy which they implement across all their jobs. Below is an extract from their policy:

“The law imposes obligations to provide a safe system of work. In addition, it also requires employees to take reasonable care of their own safety and also that of their colleagues. The possession, use or supply of drugs and alcohol is strictly prohibited…

…Where the company suspects that you have consumed drugs or alcohol…[it can]…request that you attend…an examination…In addition the company undertake random tests…”

In the UK, random testing is allowed and can take place at any time. In Ireland, the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work 2005 Act Section 13(c) clause is a very grey in the sense that it is there to be done but difficult to enforce unless clear stipulated in the employee’s contract.

Sisk implemented the procedure on the Temple Quay, Phase 3 project in order to prevent personnel being on site while under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol.

All personnel were informed, as part of the induction to site, of the company’s Substance Abuse policy and informed them that random drug and alcohol testing would be carried out every six weeks during the project. Two personnel from site would be randomly selected and taken to a clinic where they would be tested, with the target being to test 5% of the workforce every six weeks. As the site was small, it wasn’t feasible to have a full time testing facility on site.

The Site Manager confidentially arranged the test date and two appointments were booked into the clinic. All site personnel including management, sub-contractors and agency personnel names were included and two names were selected at random. Those chosen were taken to a clinic by a member of site management and accompanied at all times.

An alcohol test (breathalyzer) was carried out and a urine test was also carried out for a definitive alcohol and drugs assessment.

Test results were reviewed after they were issued and if levels reported were above the threshold value, the individual concerned would be instructed to stop working and leave site immediately. All individuals were given a copy of their test report.

Additionally, Sisk site management continually observed personnel for any drug and alcohol abuse symptoms throughout the project and if they suspected abuse they were sent for testing.

Toolbox talks were given throughout the course of the project to remind personnel that they must not be on site if under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol. (Considerate Constructors Scheme, 2016)

Case Study: Ballymore

In order to help raise standard on-site, Ballymore put together a series of health and safety awareness features. The London City Island Project is a great example of a project the which a coordinated effort to tackle the alcohol and drugs issue by keeping the topic on employee’s minds by means of visual aids. The implementation of on-site testing and easily accessible support systems shows that the company is committed to a direct action approach to the situation.

The company’s drug and alcohol policy includes a clear annual and random testing regime of nothing less than 20% of the workforce. Guidance and support systems will be offered if an individual states their drug or alcohol problem before being testing, encouraging an attitude of seeking help. Similarly, anyone refusing a test shall face disciplinary actions.

Drug and alcohol toolbox talks have been constructed with a designed approach to educate the workforce on the important information on drug and alcohol use. The site has incorporated resources from the health and wellbeing service; Compass, along with information of their own. Included in the presentation is the following:

- Drugs and alcohol statistics;

- Definitions and examples of each drugs class;

- Consequences of being convicted for each drug class;

- The effects and impacts of being addicted to drugs;

- The effects and impacts of being addicted to alcohol.

Providing a greater and more contextual understanding to drugs and alcohol gives individuals the knowledge to make better decisions, avoiding what can be life changing and leading them down a dangerous path. FRANK is a contact source for drug support and advice service.

As well as advertising a direct advice centre through toolbox talks, the site has also implemented an alternate means for support. A site phone has been provided for anyone who does not feel comfortable expressing themselves to the site’s own advisors. Details of Construction Industry Helpline are provided that also serve as a support and advice centre for various concerns including drugs and alcohol.

Visual reminders have been incorporated onto site through ‘Here is my reason. What is yours? posters that focus in being safety conscious.

The posters serve as a way of portraying why it’s important to stay alert and maintain safety, with a thoughtful reason in mind. Although this is not solely associated with the risks of drugs and alcohol, it emphasizes health and wellbeing on site, demonstrating a caring and proactive culture.

Ballymore have implemented a number of means to raise the awareness of drugs and alcohol on-site at the London City Island Project as well as offer channels of support that are easily accessible. The project demonstrates a great example of how easy it can be to introduce direct and effective features to site health and safety plans. (Considerate Constructors Scheme, 2016)

Case Study: Mulalley & Company Limited

Mulalley see the misuse of drugs and alcohol as a serious health and safety concern and like various other companies in the industry, their approach to tackling this is firm and direct. Mulalley has a zero tolerance drugs and alcohol policy for employees and also employees of any companies working on their sites or facilities.

The policy is clear in its approach to all substances from over-the-counter prescription medications to illegal drugs, all holding equal weight and strict consequences. Although the drink-drive limit is 80 milligrammes of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood, the limit at Mulalleys is strictly zero.

Mulalley understand that if any substance is expected to or presents a possibility of physically and/or mentally affecting an employee’s ability to perform can cause a risk to health and safety. An individual must inform their employer of any over-the-counter medication so it can be assessed whether or not they’re fit to work.

Should an employee be involved in an accident at work or appears to be unfit through suspected alcohol or drugs use, they may be ordered to a drugs and alcohol test by approved external testing organisation. Raising and maintaining awareness of the company policy at site induction with toolbox talks and posters on site is a constant reminder of why the workforce should be considering their commitment to their own health and safety and other’s.

Mulalley has FORS (Fleet Operator Recognition Scheme) Silver accreditation and as part of this all Mulalley company van drivers undertake FORS online training including “work related road safety” which specifically discusses the risks and dangers of driving under the influence of alcohol and drugs.